Cocreation for impact has been saved

Cocreation for impact Tackle wicked multistakeholder problems

10 minute read

01 November 2019

Complex, multistakeholder challenges don’t often present a single obvious solution. Cocreation—where the stakeholders share responsibility for the problem—can be an effective way to unlock solutions.

The dire consequences of accelerating climate change and global warming are well known. According to a report by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, dwindling resources, including food shortages, could trigger violent conflicts or even revolutions, and critical species could become extinct—leading to a collapse of the entire ecosystem.1

Learn more

Explore the government and public services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Global warming poses a more complex challenge than an epidemic or a space race—in part due to multiple stakeholders’ competing interests. Developing nations want to lift families from poverty through jobs in coal, oil, and gas; oil corporations are answerable to shareholders; and suburban infrastructure is designed around cheap fuel, and politicians’ popularity could be threatened by energy price shocks.

Complex challenges such as global warming that include multiple stakeholders with intertwining or contradictory interests are often called “wicked problems.”2 They present multiple possible approaches but no obvious single root cause or solution. Other such wicked problems include homelessness, rural access to safe water and sanitation in developing nations, the opioid epidemic, and political corruption. They shift faster than our ability to fully understand their components. Each is a symptom of another problem and has no one right answer, just approaches that improve the situation. In other words, wicked problems are everyone’s problem—and no single stakeholder’s responsibility.

Because wicked problems have multiple stakeholders, a cocreation approach— in which the stakeholders share responsibility for the problem and together develop a process for solving it—can be an effective way to unlock solutions.

However, wicked problems can be “unlocked.” “Solved” is too strong a term for such persistent issues, but a coordinated, design-thinking approach can detangle and mitigate formerly intractable challenges. AIDS, for example, is far from eliminated. However, a cocktail of public health policy, drug development, activism, and cultural change has constrained its spread in Western countries and made life livable for people who contract it. The annual rate of HIV infection in the United States fell by 8 percent between 2010 and 2015, and decreased by as much as 15 percent in certain populations.3 This success came about thanks to massive coordination by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), financing from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as the Global Fund, coordinated response plans at the national level, and contributions from NGOs, research universities, and the private health industry.

This example shows that because wicked problems have multiple stakeholders, a cocreation approach—in which the stakeholders share responsibility for the problem and together develop a process for solving it—can be an effective way to unlock solutions. This report proposes a cocreation framework that helps users map a challenge from a variety of perspectives, analyze that information, recruit unlikely partners, and collaborate toward common outcomes.

How does cocreation work?

Cocreation has, in the past, proved to be a key lever of positive change. Take the issue of homelessness in the United States. From 2010 to 2016, an ambitious US government-led initiative reduced the level of homelessness among veterans by 56 percent,4 with some states in effect eliminating the problem.5 This effort started with leaders of the respective government agencies articulating a shared strategy: provide housing first, based on the assumption that jobs and mental health require a foundation of stability. Then they shared data and best practices among a wide network of municipalities and NGOs. The effort was successful in part because of the involvement of disparate groups that would have otherwise been reluctant to participate (including politicians).

Another example of cocreation in action is the initiative to redirect 40 million tons of America’s annual food waste to 49 million Americans who would otherwise go hungry.6 At a local level, efforts such as the Food Recovery Network address the “last-mile” equivalent of supply chains, by collecting unused good food from college dining halls and events and getting it to hungry mouths.7

By creating empathy with users, design thinking reframes the challenge in a way that enables other participants to contribute to a shared solution.

While cocreation is sometimes considered an alternative to corporate social responsibility (CSR), it should instead be considered a key element of it—essentially, cocreation is “doing good without business tradeoffs.”8 In the food waste initiative, software programs higher up the supply chain are using software analytics to find patterns behind food waste; some kitchens using this software have cut food waste by 80 percent.9 The Daily Table, a business by a former president of Trader Joe’s, uses a quick-turnaround model to cook food that might otherwise wilt on shelves.10

Leveraging the power of design science

Wicked problems, with no obvious single root cause, can contain infinite potential solutions with an infinite number of possible activities, none of which can be tested prior to execution. No solution is right or wrong—only appropriate or less appropriate. In other words, a wicked problem is a design problem,11 meaning that the problem is only understood through its solution design. Here’s where design thinking can be applied to aid the cocreation approach.

Design thinking at the outset focuses on human beings. So, the lens of viewing wicked problems changes from an organization’s resource perspective or the system’s perspective to an experience perspective: How is the problem perceived by the users, clients, customers, managers, leaders, and other stakeholders? Design thinking, by creating empathy with users (such as patients),12 reframes the challenge in a way that enables other participants to contribute to a shared solution.

Public sector organizations are redesigning along these principles. Contractors getting a building permit in New Zealand can follow their application through a transparent process, practically from desk to desk, like tracking a postal package. To reduce improper unemployment benefits, the state of New Mexico started by considering how benefits applicants think. Using the concept of behavioral nudges, the state government found that by showing applicants a popup message about honesty, “a quarter of claimants are more likely to report their actual income.”13 This helped New Mexico cut unemployment insurance fraud by 60 percent.14

User-centric design utilizes three main tools:

- Empathy. For a designer, empathy means imagining the challenge from the user’s perspective—understanding the pressures on them, their needs, and options—often through extensive research, interviews, or even observing as someone fumbles through a user interface.

- Reframing. It’s about shifting the boundaries on how users think about an issue. It means deliberately shifting how people see the terms of a choice. One way to do this is by reframing wicked “problems” as “challenges.”15

- Prototyping. Prototyping is about feedback. Creating visual or tactile representations of a solution allows designers to gauge its real-world efficacy.

This design framework contributes to cocreation initiatives by creating a foundation that ensures dialogue, transparency, and risk assessment between the actors in the initiative,16 as well as providing a structure for the micro-, meso-, and macrolevels of cocreation.17

Strengthening the process of cocreation using strategic visualization

Strategic visualization is the art of reframing a question visually. Wicked challenges ask us to understand complex dynamics that resist comprehension, so it helps to visualize relationships between the forces at play, thus visually reframing the challenge.

Strategic visualization enables groups to work on complex issues by creating clarity, serving as a foundation for decision-making, and allowing groups to discuss and qualify processes collaboratively, enhancing the process of cocreation.18 In practice, strategic visualization doesn’t have to be fancy. It can mean cartooning live notes on a whiteboard during a brainstorming session, facilitating an information-gathering activity by asking participants to respond on premade illustrations, or summarizing research into a literal map of a market ecosystem. It encourages attacking a problem with one more cognitive strategy, especially for visual thinkers.

Working on wicked problems in multistakeholder settings can entail managing many moving parts. Strategic visualization is Theseus’s red thread throughout the process of cocreation. It gives the involved partners an overview of the complexity, allowing them to communicate clearly with each other and external stakeholders without getting lost in details and internal battles.19

A five-step process for cocreation

While principles such as design science and strategic visualization help facilitate teamwork and develop solutions, the following process (figure 1) is a systematic approach that can help government organizations understand the need for cocreation, identify the right partners, and engage with partners for meaningful outcomes.

This five-step cocreation framework has yielded some degree of success for organizations that tried to use it to deal with wicked problems. Consider, for instance, Energinet, an independent public enterprise that owns, operates, and develops the transmission systems for electricity and natural gas in Denmark. It faced the challenge of becoming a credible frontrunner in the conversion to a sustainable transmission system by tapping into different renewable energy sources. It was a clear case of a wicked problem—there were multiple stakeholders, no definite cause, and multiple solutions. Energinet used the five-step cocreation process to tackle the challenge.

Phase 1: Decision-making

Before initiating the formal cocreation process, two basic questions need to be answered: “Do we understand the full scope of the problem?” and “Can we solve it ourselves?” If the answer to both questions is “no,” then the challenge at hand can benefit from a cocreation approach. Cocreation as an approach provides the dual advantage of engaging actors in contributing to the solution as well as equipping the primary stakeholder with tools necessary to gain a holistic understanding of the problem.

Energinet faced difficulties in defining the exact scope of the problem and could not work out the barriers posed by its existing governance and operating models. While it had the technologies needed to complete conversion to a sustainable transmission system, the goalpost was still far away. In other words, it was caught up in the complications of cocreation.20

Energinet embarked on the cocreation journey by defining guiding principles that ensured an aligned perception of the project outcome.21

Phase 2: Mapping

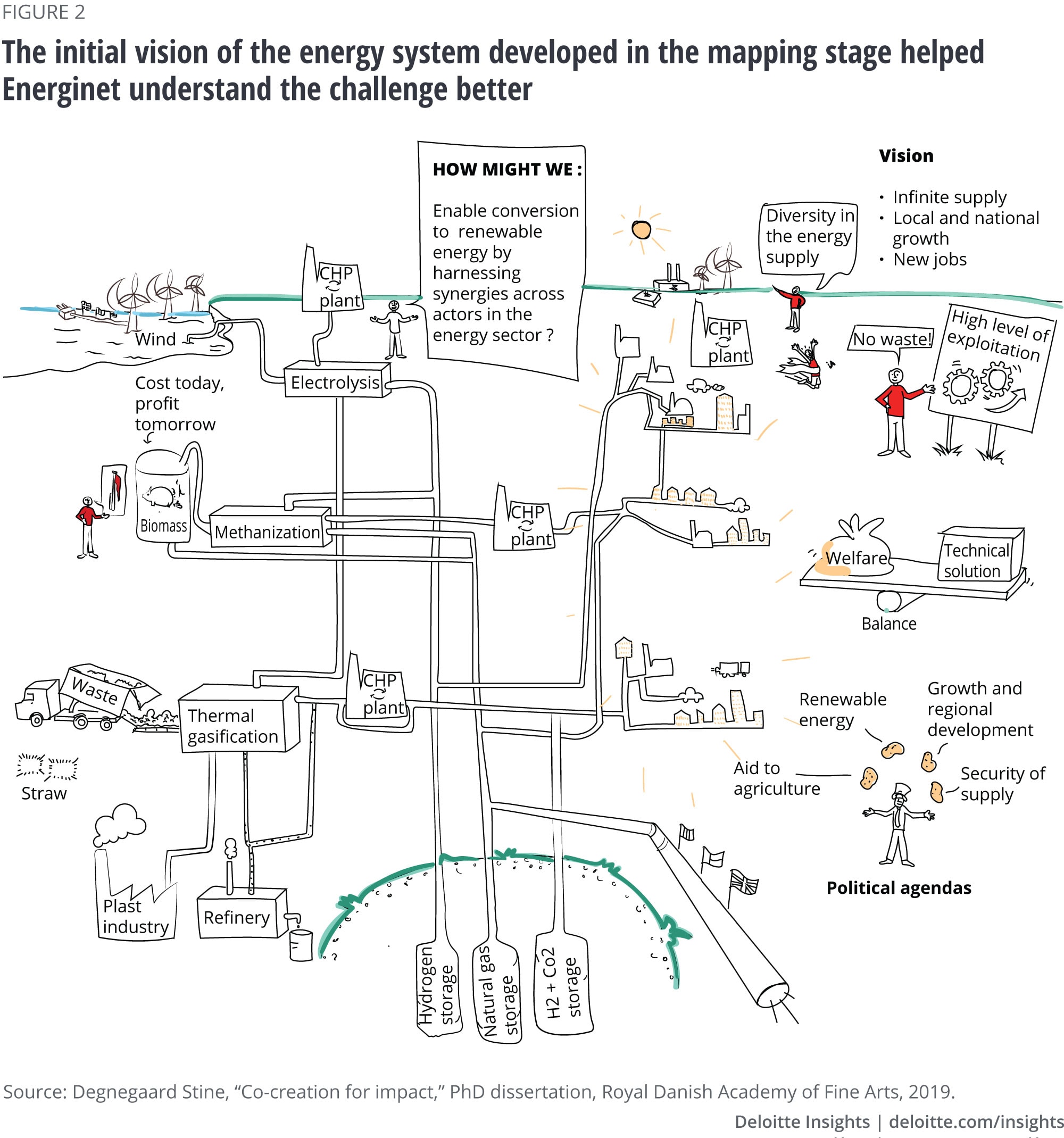

In the mapping phase, the challenge is illustratively explored through the lens of multiple stakeholders, layered with other perspectives such as related to systems, legislature, the business, and users. This phase provides three distinct benefits. First, a visual understanding of the synergies (such as by using strategic visualization) across actors helps in identifying potential areas of cooperation as well as areas of conflicting business models. Second, by bringing together disparate perspectives on a single board, it facilitates in rearranging information in new ways to clarify the links between challenges across the different perspectives. Last, visualizing the business environment aids in identifying the optimal starting point of the solution.

Energinet’s operating model made it hard to define the role of the end users. So, it deployed a systemic approach to map the challenge. It studied the developments in the energy field, recognized the relevant actors, laid down the connections between them, and identified their business models, among other aspects. Then, it turned to strategic visualization to map the entire landscape of actors (i.e. companies, interest groups, politicians—within and outside the energy sector), their relationships, and the related technologies. The illustrative landscape helped in singling out the key area of the challenge that needed to be addressed to pave the way for a complete systemic transition. It provided Energinet with a starting point to initiate the wider, long-term transformation across the transmission system.22

Phase 3: Analysis

After visually laying out all the information in the mapping stage, the primary stakeholder then explores the problem, analyzing its cocreation partner, and envisioning their eventual cocreation relationships. This phase also entails readying a battery of questions to pose to actors around the table to further drive the process. The analysis phase provides a few essential contributions to the process of cocreation. First, it helps in understanding the problem solely from the primary stakeholder’s point of view. Second, it lays down clearly the vision of the cocreation process. Lastly, it aids in identifying the relevant actors to include in the process.

The visual developed in the mapping phase (see figure 2) enhanced Energinet’s understanding of the challenge and provided a vision of how a good energy transmission system should be designed. This vision also made it clear that the relevant actors in general had difficulties in connecting the green technologies into a single system. To scale the benefits of the individual technologies to a societal scale, Energinet needed to integrate the technologies. However, it did not know how the design of a coherent and integrated system of all the available technologies should be developed.23

On this basis, the key challenge was defined as a question: “How might we enable conversion to renewable energy by harnessing synergies across the energy sector?”24

Phase 4: Involvement

The involvement phase is when you finally reach out to potential partners. It can be tricky. Sometimes, other stakeholders in an ecosystem see each other as competitors, clients, or service providers—not as partners.

If the analysis phase answers the question of which partners to contact, involvement works out how to motivate them. It provides an opportunity for participants to listen, clarify common ground, and identify partners’ needs and priorities.

To engage and motivate the relevant actors, Energinet presented its initial understanding of the problem (gathered from phase 2) to the individual actors and invited them to contribute with their view on the problem and the possible solutions within the scope of the guiding principles outlined during the decision phase. Through this exercise, Energinet convinced the actors that the necessary background work was done and sought the actors’ inputs to validate and further the understanding of the problem. This set the stage for the engagement phase, where actors felt invited to codevelop the solution with the primary stakeholder, Energinet.25

Phase 5: Engagement

The previous phases lay the foundation for the actual development of the solution. Trust had been built, dialogue had been initiated, transparency across actors had been established, and potential risks had been identified. The engagement phase is all about coming to the nuts and bolts—specifics and mechanisms in the proposed solutions.

For Energinet, the focus of this phase was to calculate the expected effects of integrating the technologies in a coherent system. It envisioned a multistakeholder operating model, with the implications for various actors clearly spelled out: What would the expected costs and benefits be? Which pricing mechanisms need to be integrated? And how to ensure that all actors could achieve the expected long- and short-term goals?26

Answering these questions required the formation of a close-knit group. The cocreation framework not only ensured that the relevant actors were included, it also developed a common understanding of the problem—one of the most important drivers in unlocking potential solutions to wicked problems.

Cocreation is dynamic

In a world of wicked problems and conflicting incentives, the public sector has an opportunity to convene multiple stakeholders to discuss how to reshape entire markets. Cocreation is a delicate task. The cocreation framework, evolved via multiple experiments and case studies, offers a systematic approach to navigate the weeds. Like any real-world system, it can evolve in response to circumstances and results.

Learn more about problem solving in the public sector

-

Government & Public Services Collection

-

Addressing homelessness with data analytics Article5 years ago

-

Customer experience in government Collection

-

A new mindset for public sector leadership Article5 years ago

-

Service design in government Article5 years ago

-

The Reimagine Learning network: Tackling persistent problems Article6 years ago