Job-centric upskilling The new workforce development imperative

22 minute read

29 September 2020

Skills are more important than ever in today’s pandemic-affected economy. Job-centric upskilling can benefit job seekers, companies, and the economy as a whole by going beyond training and focusing on capabilities for specific jobs.

Key takeaways

Job-centric upskilling: Three key factors

What if there was a way to help job seekers get better jobs, while providing employers with the sort of skilled labor they need? What if there was a way to help disadvantaged, displaced workers while also helping companies diversify their workforce? What if incumbent workers could be prepared to succeed in the jobs of the future?

All this, in a nutshell, is the potential of job-centric upskilling.

Learn more

Explore the government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Instead of starting with the person who needs a job, job-centric upskilling starts with the job that needs doing. But what does job-centric upskilling entail? What makes it successful?

Successful job-centric upskilling covers three key factors:

- Train: Trains candidates in the skills for a particular job

- Support: Provides them with needed support on the job

- Measure: Measures results of the job placement

With traditional job training, organizations teach individuals the general skills they think companies need, in the hope the job seekers will have greater success in the labor market (figure 1). Too often, getting the trainee hired—or even worse, just graduating from the training—is viewed as the end of the process.

In contrast, job-centric upskilling sees the skills training as only part of the journey to success. Getting the job seeker employed is important, but real success requires that individuals thrive in their jobs, and the company is pleased with their performance. In most cases, job-centric upskilling doesn’t involve generalized training—it trains with a specific job in mind. Moreover, the initial training is followed by maintaining a connection with not only the job seeker (through on-the-job support) but also with the hiring company, to measure success months down the line (figure 2).

The urgent need for job-centric upskilling

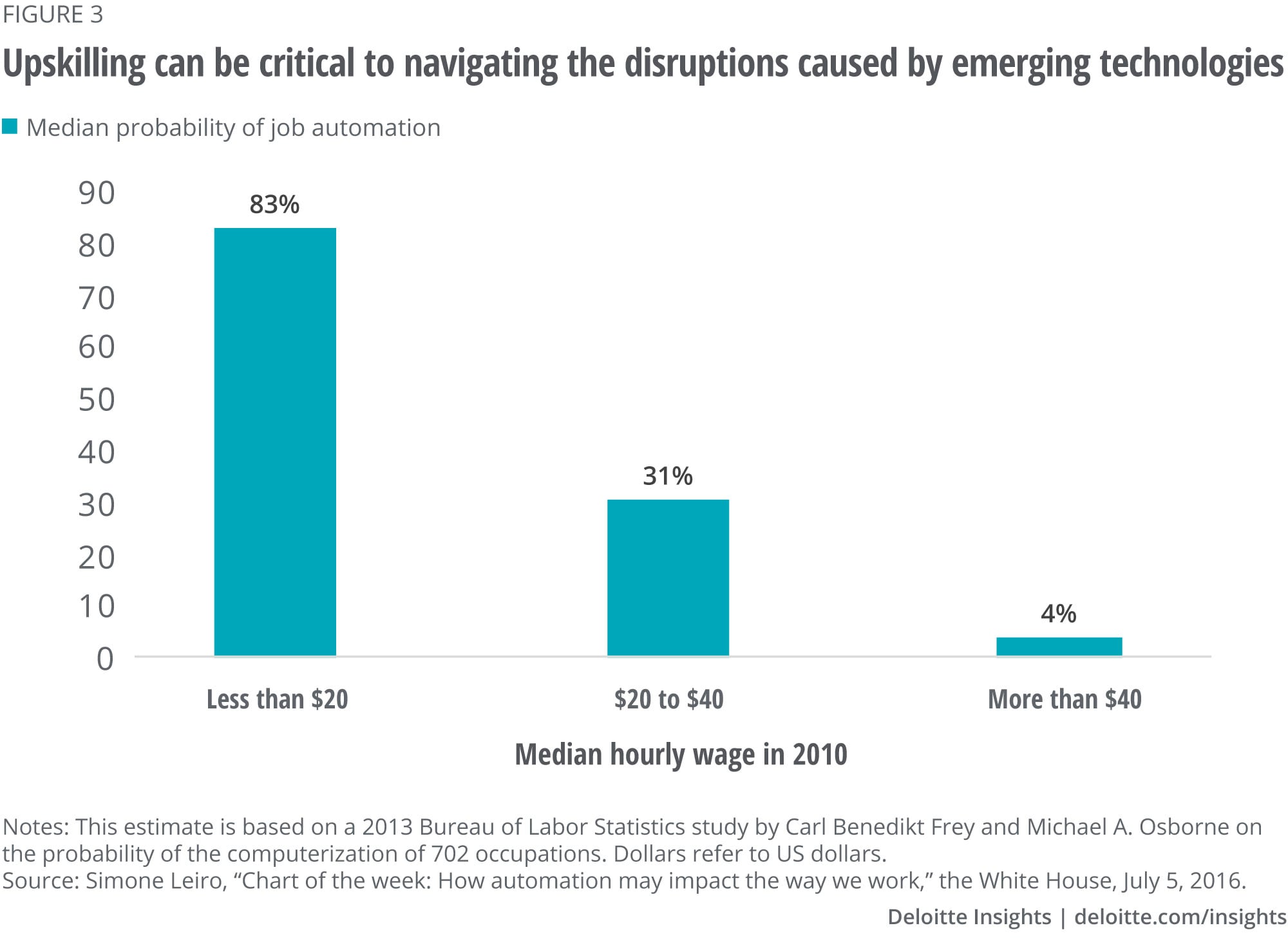

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the US economy was facing a skills gap. Though unemployment was low, many workers were struggling in low-wage and “gig” economy jobs. Automation and offshoring were placing jobs at risk—especially for lower-wage workers (figure 3).1 At the same time, companies were struggling to find the skilled workers they needed to grow.2

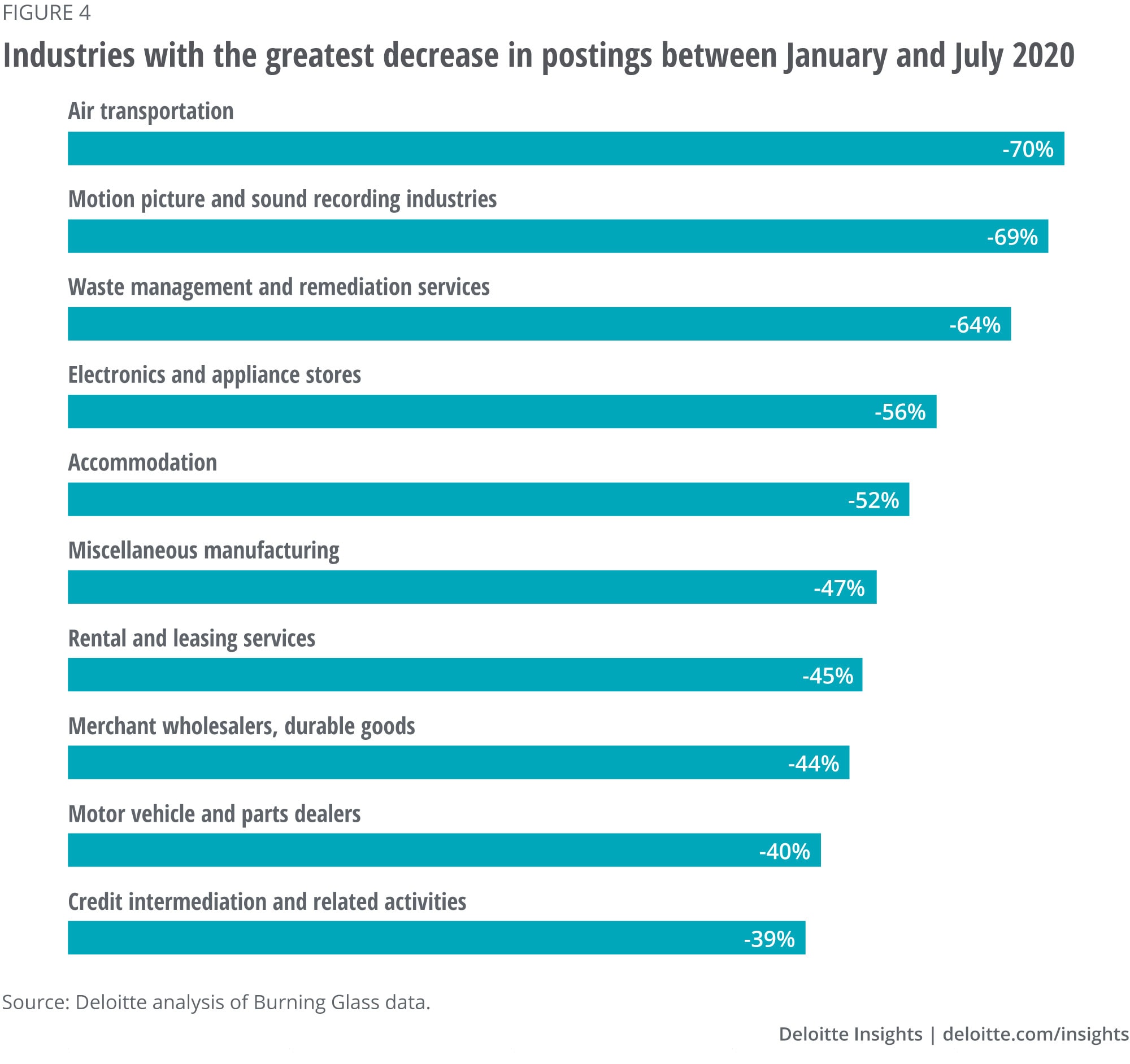

The onset of the pandemic in the spring of 2020 prompted massive global economic disruption, with unemployment levels not seen since the 1930s’ Great Depression. Entire industries, such as travel, tourism, and hospitality, are facing an ongoing crisis (figure 4). Researchers at the University of Chicago project that 32–42% of COVID-induced layoffs will be permanent.3 They also contend that while the disruptive shock to the economy was rapid, the shift to new forms of work will evolve over time:

Historically, creation responses to major reallocation shocks lag the destruction responses by a year or more. Partly for this reason, we anticipate a drawn-out economic recovery from the COVID-19 shock, even if the pandemic is largely controlled within a few months.4

Moreover, the pandemic has accelerated the push toward more digital and virtual workplaces, bringing the “future of work” into the present more rapidly than expected.

Currently, we are in a period of a massive reallocation of labor. No one knows precisely what the future will look like, or what the jobs of the future are going to be, but enhanced skills will likely be a crucial part of the recovery. Already, the US Department of Labor has expanded the Dislocated Worker Grant program by US$100 million to provide training and temporary employment to dislocated workers.5 Job-centric upskilling should be considered as a component of this reskilling effort.

A tailored approach that works for different types of job seekers

One key aspect of job-centric upskilling is that it can be tailored to meet the needs of companies and job seekers. The balance between training, support, and measurement can change based on the candidate’s experience and demands of the job. Three scenarios demonstrate how job-centric upskilling can be adapted to very different situations.

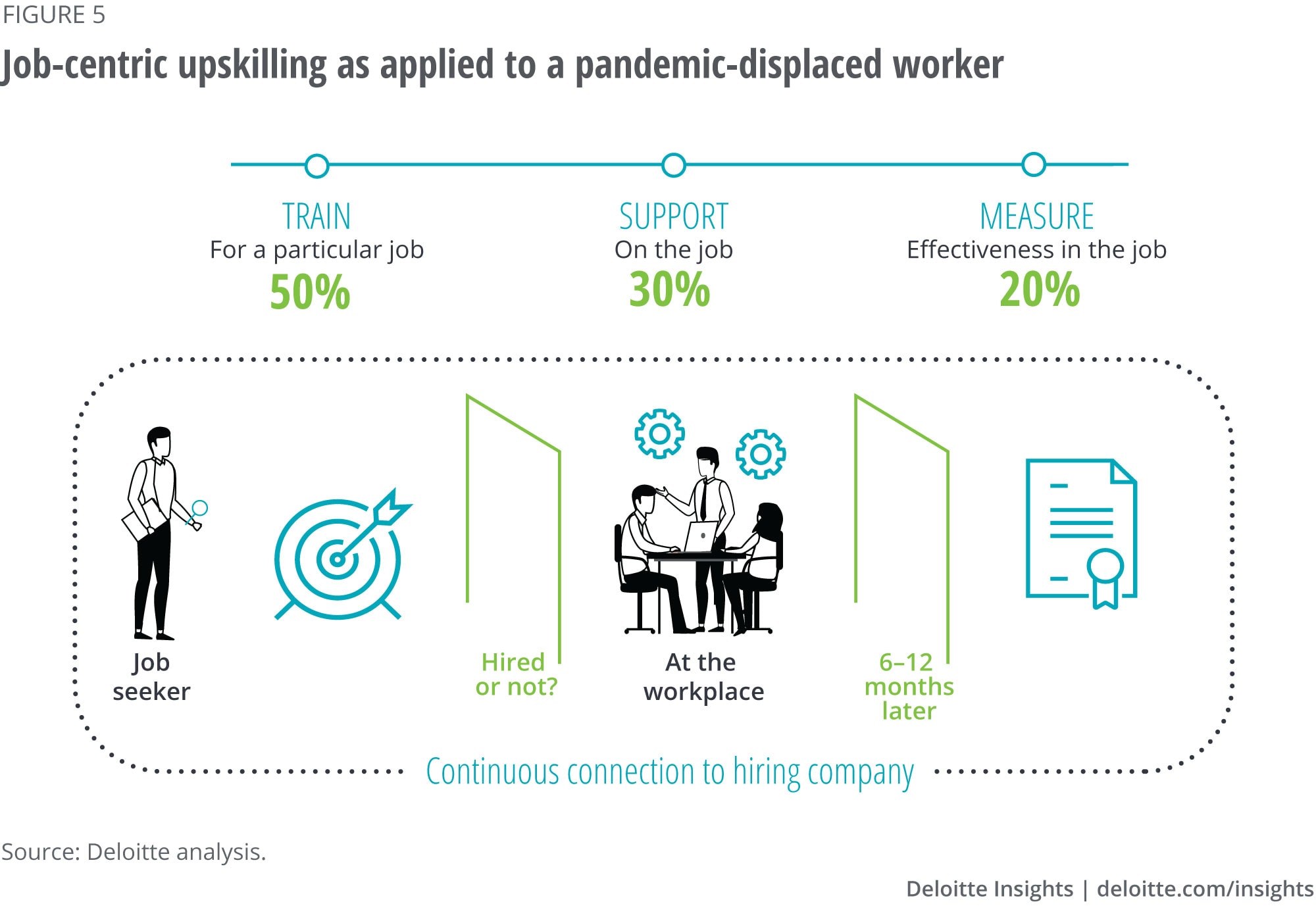

Scenario 1: Reskilling a pandemic-displaced worker

Job-centric upskilling can help workers who have been laid off due to the COVID-19 pandemic, preparing them for jobs in expanding sectors of the economy. Because these workers likely have good basic competencies but need to be trained on jobs they haven’t done before, the training element of job-centric upskilling will predominate for such workers (figure 5). Training providers should ensure that the training curriculum is designed in close coordination with the target industry. Apart from training, these displaced workers might benefit from temporary income support, career counseling services associated with transitioning to a new industry, as well as psychological support to deal with job loss. Assessing the success of the transition can happen through long-term measurement. (In figure 5 and others, the percentages shown are intended to be representative; the precise balance of training, support, and measurement will depend on specific circumstances.)

Sweden has adopted such an approach to redeploy workers laid off from the hard-hit airline industry to the suddenly understaffed health care industry. Soon after the decision was made to lay off 90% of Scandinavian Airlines’ cabin staff, a partnership between the airlines, a Swedish HR company, and Sophiahemmet University was formed to create a three-and-a-half-day training for the role of an assistant nurse. About 300 cabin attendants, already skilled in providing services to passengers, have gone through the training and have found reemployment in Sweden’s health care industry, allowing nurses and doctors to focus on more medically oriented tasks. Sweden has also used this model to reskill laid-off workers from different industries for administrative roles at schools;6 Australia and Singapore have also launched similar programs.7

Rhode Island is using US$45 million of federal CARES Act funding for a public-private partnership called “Back to Work RI,” with the state providing targeted skills training along with additional support services to displaced workers to help them land jobs in growing sectors such as health care and information technology (IT).8 According to the Rhode Island governor’s office, the program will “move beyond the old ways of ‘train and pay’ to a new paradigm – train, support, and hire” by partnering with private companies to provide training along with “wraparound” supports (such as coaching, mentoring, and supports outside of work).9

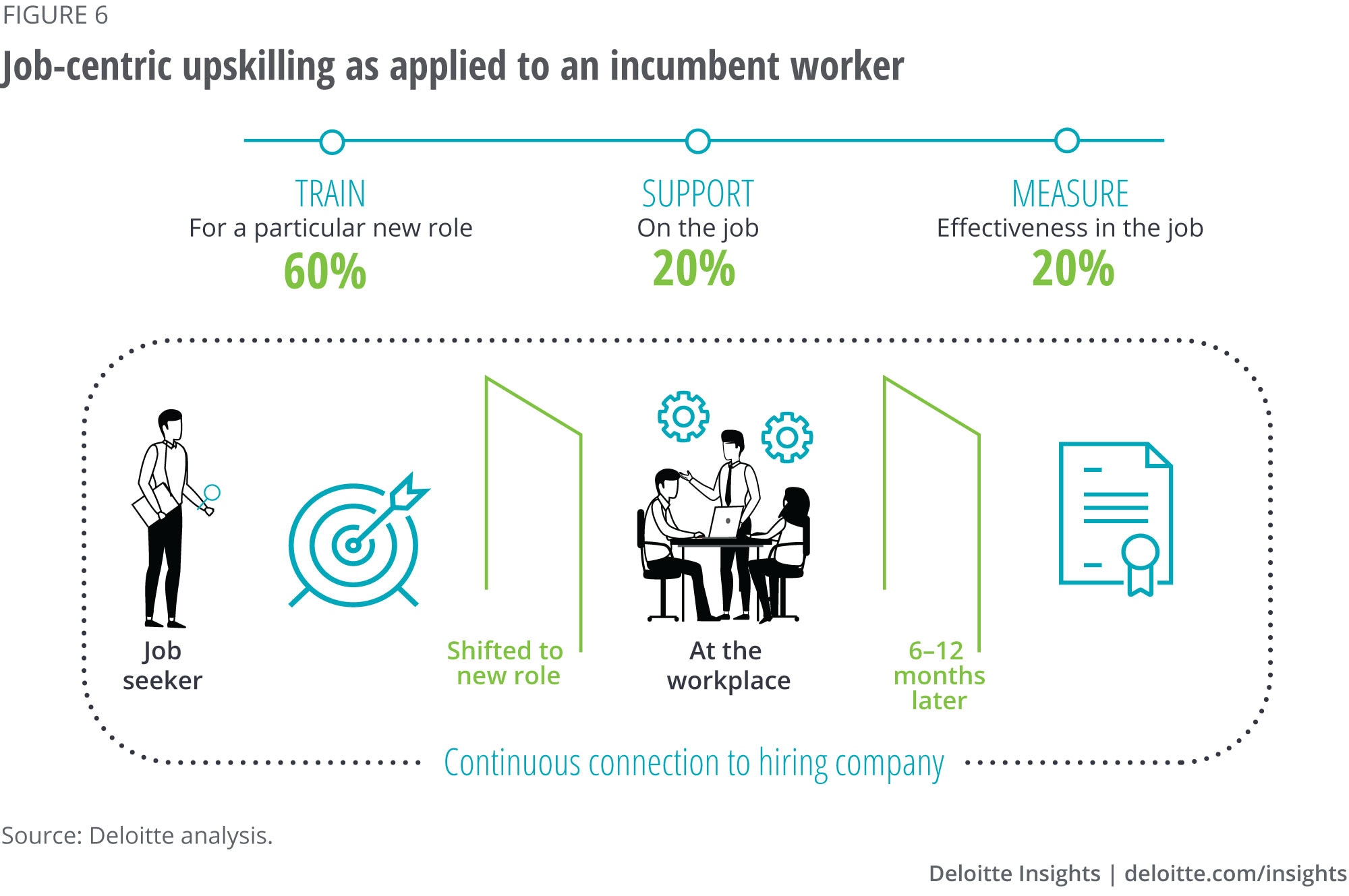

Scenario 2: New-skilling an incumbent worker

A number of companies have started their own reskilling initiatives to retrain and retain workers in industries being reshaped by automation. Because incumbent workers are already somewhat familiar with corporate culture, the main focus for them will be on developing new skills—though there will likely be some need for support and measurement (figure 6).

With employer-driven upskilling, the organization designing the training is also the employer and thus has a strong understanding of what skills are needed now and into the future. For example, in July 2019, Amazon launched Upskilling 2025, an initiative aimed at reskilling 100,000 employees for precise, in-demand roles at a total cost of US$700 million. As part of this initiative, the company is holding the Amazon Technical Academy bootcamp where its software engineers are training nontechnical Amazon employees on coding. Another such initiative is the Machine Learning University, a program designed by Amazon AI and learning specialists to familiarize employees who have some technology background with machine learning.10

It’s not just high-tech companies whose workforces should adapt to the growing presence of technology. From financial services to government, technology is reshaping the demands of work, and job-centric upskilling can help organizations bring the skills they need into the workplace of the future.

Reskilling the government workforce

As technology advances, governments at all levels are increasingly looking to evolve the skills of their workforce. For instance, in the 2020 federal budget proposal, the White House included resources to reskill 400,000 federal workers—about 20% of the workforce—in hard-to-fill roles such as data science, IT, and cybersecurity.11

As the tasks of government change, so too will the skill sets needed of government employees. For example, the Office of Management and Budget has launched a program that will train existing government employees in the growing field of data science. Beginning in mid-September 2020, the six-month program combines online training and hands-on project work.12 The US Army is also upskilling civilian workers in the emerging skills of the future. The new program, called Quantum Leap, has an initial plan of retraining about a thousand employees for systems analyst, application developer, and data manager roles by 2023.13

As cognitive technologies and COVID-19 disruptions reshape government work, public employees should be more agile, resilient, and willing to embrace an unprecedented rate of change. Comfort with technology is a part of the equation: More government work is expected to get done from home, due to which workers should adapt to virtual workspaces and learn new ways to collaborate, manage, and deliver work. At the same time, as technology offloads routine work, public employees may have greater opportunities to use their “soft” talents. Human skills such as creativity, emotional intelligence, leadership, and compassion could be more important than ever—and can’t be done by a machine.

Like many businesses, government should look to digital tools to better manage the skills of their workforce. This could include using a common taxonomy of competencies that could allow the agency to pinpoint skills shortcomings of individual employees, as well as understand what capabilities their workers have, what the organization needs, and what additional upskilling is required to close the talent gap. To learn more, see The future of work in government.14

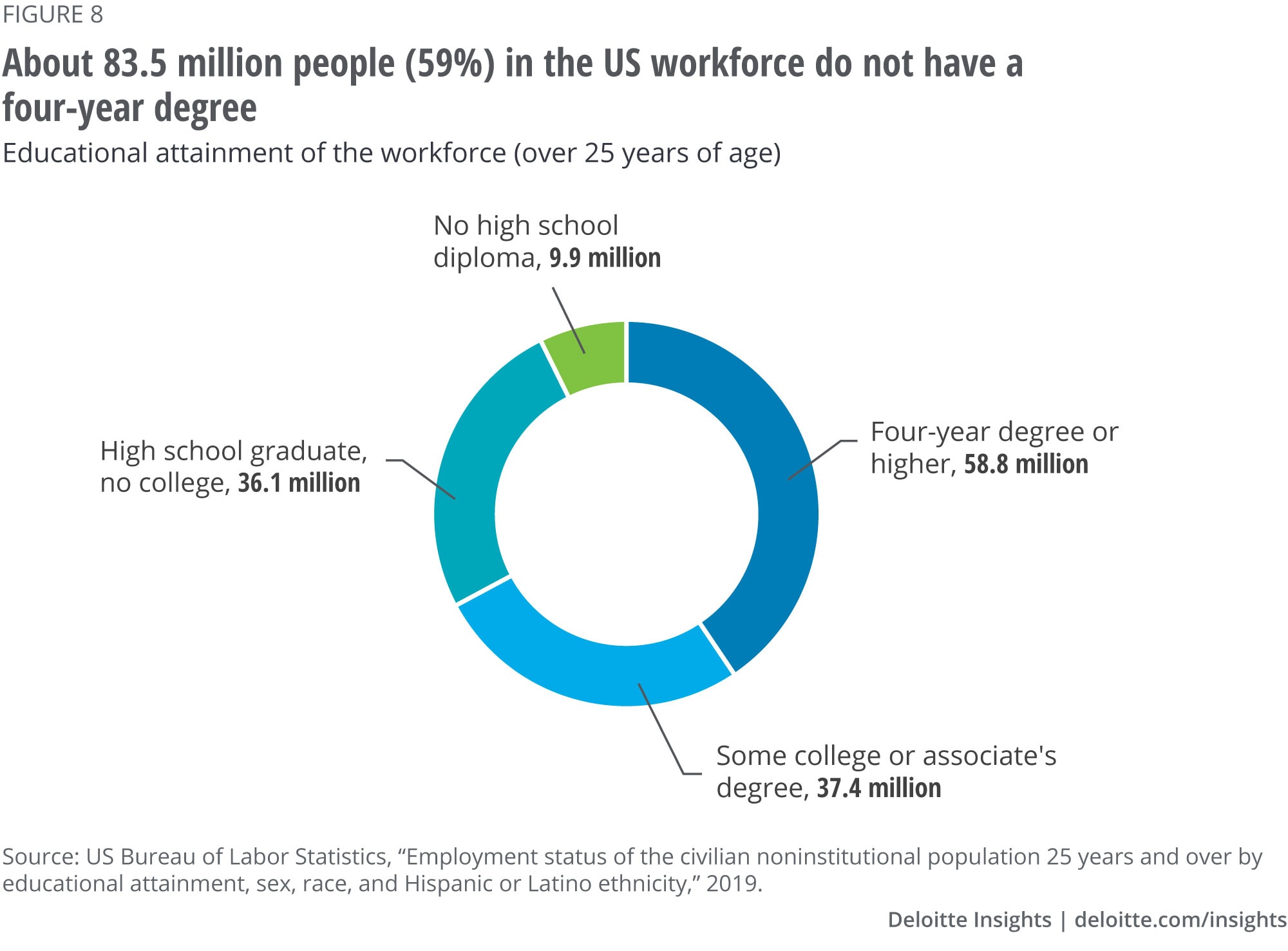

Scenario 3: Upskilling a nontraditional/disadvantaged worker

When applied to nontraditional workers, the support component typically becomes more critical (figure 7). Support can be especially important for those seeking to enter the professional workforce for the first time: perhaps struggling to get off public assistance, or transitioning from incarceration, or recovering from substance abuse or domestic violence. But even for some individuals with workplace experience but who lack a four-year degree or any postsecondary education, support can be just as critical as the “hard” skills obtained through training. As figure 8 shows, the majority of the US workforce does not have four-year degrees, so tapping into this talent pool is important.

We’ll now dive a little deeper into what precisely goes into each of these three facets of job-centric upskilling: train, support, and measure.

Training in job-specific skills

Unlike in generalized job training, the training curriculum for job-centric upskilling is created in close collaboration with the companies that do the hiring. When reskilling incumbent workers, this occurs naturally because the company itself shapes the training. In other cases, steps should be taken to ensure close alignment.

One way to do this is to have industry groups design the curriculum. In Maryland, the Department of Labor’s EARN program allows employer groups to design training programs from scratch. Employers partner with other companies with similar talent needs to submit a proposal to the state, identifying the skills they need and suggesting programs that can train people in those skills.15 Started in 2014, EARN currently funds 72 strategic industry partnerships.16 According to Tiffany Robinson, secretary of the Maryland Department of Labor, “Our innovative and nationally recognized EARN Maryland program challenges traditional workforce development programs by placing employers and industry partners at the forefront of program implementation.”17

The EARN program has found success even with difficult-to-place job seekers. For example, the Civic Works partnership provides skills training to such individuals, such as those with criminal backgrounds, to help them secure jobs in the growing field of environment sustainability. Some 246 of the 269 individuals who have completed EARN-funded training through Civic Works have obtained employment.18 Instead of “one-size-fits-all” training, EARN training is customized to specific training cohorts and industries. Overall, since 2014, around 4,500 unemployed or underemployed individuals have completed entry-level EARN training, and more than 84% have obtained employment.19 “EARN Maryland is helping Maryland’s businesses cultivate the talented workforce they need to successfully compete and grow in our ever-changing economy,” says Robinson.20

The Apprenti upskilling program, run by the not-for-profit Washington Technology Industry Association, is another job-centric approach to upskilling.21 Apprenti partners with state labor departments and is designed to help nontraditional populations break into the technology industry.

Apprenti’s approach has three elements. First, instead of starting with the worker, Apprenti begins with identifying open positions in technology companies. “We don’t start training until we have identified the jobs for those who will graduate the program,” says Rosalin Acosta, the Massachusetts secretary for Labor and Workforce Development, who noted that the program has been helpful in promoting diversity in the IT field.22

Second, where typical internships last three to six months, Apprenti provides technical training for two to five months, followed by paid on-the-job training for one year. Finally, on completion of the program, participants receive a certificate documenting their occupational competence. This innovative training model has helped Apprenti achieve a high success rate: About 75% of its first batch of 130 students who graduated in 2018 found permanent positions at companies at a median annual salary of US$78,000.23

It’s not just governments that are recognizing the benefits of job-centric upskilling. Non-profit workforce organizations that seek to lift people out of poverty are also seeing the benefits of focusing on company success. In its review of what constitutes a strong “next-generation workforce provider,” the Boston Foundation, a leading Bay State non-profit, noted how important it is for such organizations to be “market-responsive.”24 In a December 2019 report, it identified several ways to better align with the businesses that offer employment, including:

- Having a dedicated team to oversee employer relationships

- Being flexible and willing to learn together with the business

- Setting up employer advisory councils or similar groups

- Creating talent supplier agreements with local employee groups25

In other words, though its ultimate goal is to help disadvantaged individuals, the foundation also recognizes that industry success is critical to worker success.

About next-generation workforce providers

In 2019, the Boston Foundation and SkillWorks launched Project Catapult, intended to be a new way of thinking about workforce development as a tool for social advancement. In conjunction with the Monitor Institute by Deloitte, they conducted in-depth research into what they call “next-generation workforce providers”—market-driven training and education providers seeking to expand opportunities for lower-income individuals.

Their December 2019 report, Catapult forward: Accelerating a next-generation workforce ecosystem in Greater Boston, examines the workforce ecosystem in the Boston area.26 The report makes four broad recommendations for improving outcomes for workers and employers alike and closing the talent gap:

- Be market-responsive: Providers should develop deep partnerships with companies and tailor programs to employer needs.

- Focus on the “good jobs”: Good jobs are defined as those that meet the distinct needs of participants; their characteristics can include compensation, career growth, economic mobility, or flexibility of work schedules. A good job might look different for different demographics.

- Lift untapped talent: Tailored skills training is important, but it is often critical to providing other “wraparound” supports that can help job seekers succeed.

- Invest in organizational capacity: The report urged next-generation workforce providers to build internal capabilities for continuous improvement, use data to measure program quality, and tap into unconventional funding sources to boost sustainability.

While the report focused on nonprofit next-generation workforce providers who typically work with disadvantaged populations, the lessons can have broader relevance for those seeking to move workers up the skills ladders—including incumbent workers.

Providing needed support

Generalized job training puts the emphasis on training instead of success in a new job. But some job seekers, particularly those from nontraditional and disadvantaged backgrounds, may need more than just the functional “hard skills” to succeed in a work environment.

It’s one thing to know how to weld, bake, or fix a car, but other “employability skills” can be critical as well, such as knowing how to serve customers, interact with coworkers, or communicate appropriately with a manager.

Some individuals may need support to succeed at work. That’s because some nontraditional hires come from difficult life circumstances, and the so-called “social determinants of work”—such as housing, child care, transportation costs—can affect their ability to learn and work. As a result, some may need support that goes beyond skills training. Additional support can also help challenged population segments such as older workers, single parents, and those with physical challenges.

Upskilling support strategies can be customized to a specific population—such as high school dropouts, those with limited language abilities, single parents, former prisoners, and older workers—and sometimes even to a specific individual. Some common support strategies include providing:

- Practice employment environments

- On-the-job mentoring, including alumni support

- Holistic, wraparound “life supports” outside of work

Practice employment environments for challenged populations

Providing practice employment environments can be useful for individuals with limited work experience. More Than Words (MTW), a Boston-area nonprofit, aids young adults who are in the foster care system or in other possibly challenging circumstances. Program participants, for example, might work 20 hours a week managing MTW’s bookselling business or other endeavors. This helps them gain experience that external employers value. By providing a “practice” employment environment, MTW sees approximately 80% of its graduates either at work or in school after exiting the program.27

On-the-job mentoring

Providing holistic support to help those in new jobs can be an important component of an effective upskilling program. For instance, the New England Center for Arts and Technology (NECAT) is a nonprofit in Boston that combines culinary skills training with social-emotional training designed to help individuals with challenging personal experiences succeed in the food services industry. As NECAT staff put it: “Students come to us with serious challenges, and we incorporate that into the way we teach. We are more than a cooking school; our program is balanced with all of the life skills that people need to help them along the journey.”28 This holistic training approach has improved the employment rate of NECAT participants by 30% in 2019 over previous years. 29

Holistic, wraparound “life supports” outside of work

Job seekers are unique, and a customized wraparound support program can help improve training outcomes. For example, the Hospitality Workers Training Center (HWTC) in Toronto found that the personal needs of its participants varied widely, ranging from child care, to housing and food security, to substance abuse counseling, transportation, and more. To help participants overcome these hurdles, HWTC performs an extensive assessment of participant needs right after program enrollment. Once participants’ initial training is over, a job coach acts as a case manager who assesses their post-training needs and works with employers to address any performance issues that may impact job retention. This program, funded by the government of Canada, has helped improve the job prospects of its participants. About 80% of HWTC’s participants attain employment in Toronto’s hospitality industry within eight weeks of training completion.30

It’s not just highly challenged populations that can benefit from support. Many individuals who lack a four-year college degree may be an untapped source of technical and professional talent, and they can benefit from coaching and soft-skills training. For example, the Pathfinder program launched by Deloitte and Salesforce in June 2018 in Indiana is designed to provide participants from diverse backgrounds with not only the technical Salesforce skills, but also the business skills, mentorship, and on-the-ground experience to help candidates land an in-demand job and a rewarding career as Salesforce administrators and developers.

While the shorter-term goal is to graduate 500 students by the end of 2020 in Indiana, the Pathfinder program has already expanded to the San Francisco Bay Areas this spring, is launching in the United Kingdom and Japan this fall, and has a longer-term goal of continued expansion to new markets, organizations, and types of talent.31

Measuring results

Job-centric upskilling likely won’t be sustainable unless it can demonstrate benefit to both job seekers and the companies that hire them. That’s why it is critical to get continuous feedback from both trainees and employers. Hard data as well as more informal feedback can show what is and isn’t working—an element often lacking in traditional government training programs. (See sidebar, “Multiple job training programs, but with uncertain effectiveness.”)

Multiple job training programs, but with uncertain effectiveness

Many job training programs have struggled to demonstrate a positive impact for job seekers. In 2011, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) looked at federal employment and job training programs. The GAO found that “in fiscal year 2009, nine federal agencies spent approximately US$18 billion to administer 47 programs,” while also noting that “little is known about the effectiveness of most programs … Nearly all programs track multiple outcome measures, but only five programs have had an impact study completed since 2004 to assess whether outcomes resulted from the program and not some other cause.” So for those five programs that conducted an impact study, what were the results? According to the GAO: “The five impact studies generally found that the effects of participation were not consistent across programs, with only some demonstrating positive impacts that tended to be small, inconclusive, or restricted to short-term impacts.”32 There are some job programs that document positive results, including Job Corps and YearUp—but some are simply not measuring impact.33

Success measures can be critical to demonstrating value. In addition, qualitative feedback from participants can provide ideas for innovation. Some common ways to get these insights include:

- Gathering metrics of upskilling—and using those metrics to fund what works

- Getting qualitative feedback from employers and trainees

Gathering metrics of upskilling

Successful upskilling should boost the employment prospects of participants and provide employers with valued workers. If the upskilling is working, there should be measurable increases in the wages, employment rate of program participants, as well as an improvement in their retention and advancement rates. Collecting such data comes at some cost, but without valid measures, all the players—participants, training providers, and employers—may be flying blind.

The CONNECT program in Boston demonstrates one method to track outcomes. The program collectively manages upskilling services from five different agencies, and maintains a shared customer relationship management system. This shared system “allows CONNECT to holistically measure change in income, credit score, housing status, and other key metrics, which it uses to indicate the quality and comprehensiveness of its programming to employers and job seekers.”34

The YearUp program serves 3,500 disadvantaged urban youth in eight metropolitan areas, providing six months of training followed by a six-month internship.35 The federal Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families of the Department of Health and Human Services measured this program’s impact using a randomized control trial, which showed that participants increased earnings by 53% compared with a control group.36 This type of data is often critical in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of upskilling.

It’s also important that metrics are used to inform funding choices. For example, Maryland’s EARN program (described earlier) requires impact measures from its grant recipients and won’t renew a grant if it fails to demonstrate impact.37

Gathering qualitative feedback from employers and trainees

In addition to hard metrics, qualitative feedback from both employers and trainees can help ensure that upskilling programs are continuously improving.

According to the Catapult report on next-generation workforce providers, “organizational learning and continuous improvement” are key to running successful upskilling organizations.38 The report noted that Per Scholas, a tech-oriented next-generation workforce provider, constantly evolves its offerings trying to keep up with developing technology. In addition, it often hires a number of Per Scholas alumni as staff and invites several to serve on the board as ambassadors to inform the organization’s vision. Having alumni on staff and getting their inputs allows Per Scholas not only to improve training but also better reflect the diversity and needs of the student population.

Putting it all together

The move toward job-centric upskilling reflects a shift in philosophy: Instead of focusing on the job seeker, it is about preparing people to successfully create value for specific employers. Successful upskilling requires tight connections to the labor market, broad support for participants, and a focus on measurable results to drive continuous improvement.

Ultimately, upskilling should deliver good jobs for applicants, and that means preparing applicants who are capable of succeeding in the work environment. Employers with a strong commitment to “giving back” can be good corporate citizens while also boosting their workforce. Job-centric upskilling can help broaden the talent pool that companies can tap into, and thus the diversity of their workforce.

Organizations providing upskilling services should keep the three success factors of job-centric upskilling in mind: targeting industry needs, providing needed support, and measuring impact. But how can these be made a reality? Here are a few suggestions for policy makers, business leaders, workforce service providers, and educators to consider:

- Revisit job training: A lot of government money is spent on training, but is that investment delivering the best bang for the buck? It may be possible to use available resources for various types of job-centric upskilling and realize greater returns.

- Strengthen the ecosystem: Too often, the various players in the workforce ecosystem—universities and community colleges, workforce philanthropies, government, and especially the business community—are isolated from each other. Bringing all these groups to the table may foster win-win solutions and creative ways to pay for job-centric upskilling.

- Target upskilling for particular jobs and population segments: Job-centric upskilling is versatile, and by adjusting the mix of training, support, and measurement, can be used for a variety of both jobs and job seekers. The training, support, and jobs should all match the capabilities and aspirations of the target population. In fact, start with the job, and then figure out what type of person, with a little upskilling, could succeed in that job.

Job-centric upskilling can deliver greater value for job seekers because it makes sure that employers are satisfied. Having the interests of the employer and the demands of the job at top of mind can be essential in ensuring that individuals getting the training end up with what they want—a better job, a better future, and a better life.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the future of work in government

-

The future of work in health and human services Article4 years ago

-

Closing the employability skills gap Article5 years ago

-

Government jobs of the future Collection

-

The future of work in government Article6 years ago

-

Reinventing workforce development Article6 years ago