Planning a new presidential term amid growing uncertainties How to effectively plan for postelection amidst a pandemic

12 minute read

11 September 2020

COVID-19 means that this year’s presidential transition planning, mandated by law, could prove especially challenging. Reframing critical uncertainties into strategic choices can help agencies better prepare.

The new uncertainties

There have been several times in recent history when US presidential transitions or second terms have occurred during times of significant crisis. The Great Depression, World War II, and the 2008 financial crisis all coincided with election years. The November 2020 election will take place during both a public health and an economic crisis, at a time of social unrest, and when government business operations have been upended due to COVID-19. The combination makes planning for a potential transition or a second term the most challenging since perhaps 1932.

Learn more

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Many federal agencies are likely to have new leadership in the coming year. This is obviously true if a new administration is elected, but historically, even continuing administrations typically experience over 40% turnover in leadership positions following reelection.1 Uncertainty about this “changing of the guard” dominates much of the government landscape in a typical election year.

However, in this election cycle, that leadership uncertainty is compounded by pandemic-driven uncertainties about the state of the world. This will make this transition different—and far more challenging—whether for a new or returning administration.

Along with posing massive economic and health challenges to government, the pandemic has brought many transformational changes to daily operations. These changes include the sudden movement to telework, the digitization of services that were once provided in person, and the shift away from trends such as urbanization and gig and sharing economies. They have happened swiftly and often lack formal documentation. Additionally, many government services have been paused or reengineered, while scores of public agencies have had to drastically expand their functions and reshape their missions to adapt to the crisis.

The pandemic could also cause other major uncertainties, one of the biggest being not knowing the actual winner for weeks after election day due to delays in counting mail-in ballots. In addition, it could mean a potential transition would need to take place mostly virtually. This would post myriad challenges, such as negatively impacting the flow of information.

A four-part process (figure 1) can help agencies and transition teams better prepare to take timely action and make more informed choices in light of these uncertainties:

- Identify critical uncertainties and their relevance to the agency.

- Show the possible effects of the uncertainties interacting using scenarios.

- Analyze what this means for the organization.

- Outline a set of strategic choices that leaders can make.

Along with posing massive economic and health challenges to government, the pandemic has brought many transformational changes to daily operations.

Identify critical uncertainties and trends

Each election year, agencies prepare “briefing books” and take other steps to help prepare for a possible transition. While these exercises have tended to focus on the current state of the agency, identifying critical uncertainties and trends is also important in helping agency leaders understand what strategic choices they have.

Typically, each agency follows a well-defined process and a shared set of guidelines to onboard new leaders and familiarize them with the agency and its concerns. The materials and guidelines are specific to the situation of the agency.2 The Center for Presidential Transition at the Partnership for Public Service recommends these materials include a landing team briefing book and an “owner’s manual” for incoming appointees. These materials provide an overview of the mission and basic organization of an agency, along with administrative information such as the status of current programs, key performance indicators, agency assets, funding sources, and congressional relations.3

Historically, these materials have tended to focus on describing the “as-is” state of the agency with an emphasis on the near-term decisions that would be called for, such as upcoming budget decisions or congressional requirements. A few agencies, however, have taken a more issues-focused approach that explores critical uncertainties. In preparing for the 2016–2017 presidential transition, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) produced a leaner version of the basic materials and supplemented those with succinct two-page papers on 10 priority issues.4

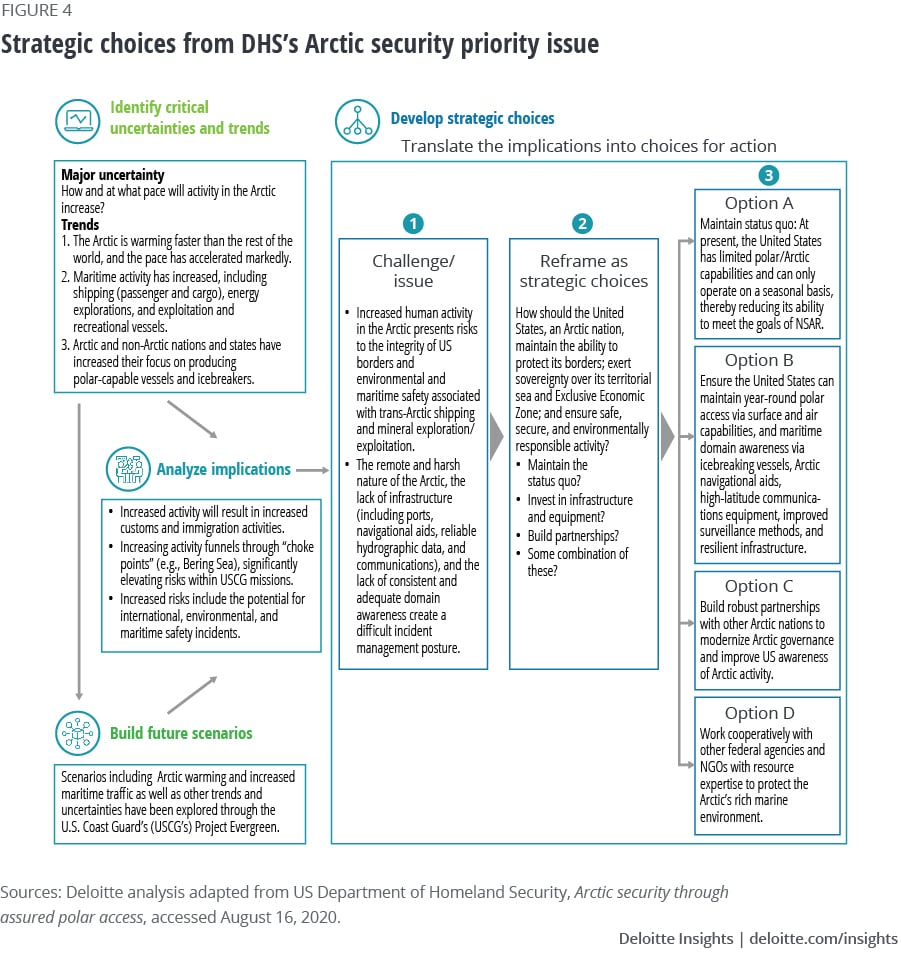

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) followed a similar approach, calling out “Arctic security through assured polar access” as one priority issue potentially involving the United States Coast Guard, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The polar issue, noted the paper, is evolving at an uncertain rate but presents potential challenges due to five underlying but related trends: accelerated Arctic warming, increased commercial and recreational activity, anticipated increases in customs and immigration, increasing travel through vulnerable “choke points,” and increased production of polar-capable vessels by a number of nations.5

The DoD and DHS (along with agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the United States Environmental Protection Agency [EPA]) tend to focus more on crucial trends and uncertainties in their transition materials than other agencies because their missions require them to anticipate the uncertain behavior of enemies and disruptions (e.g., an oil spill, a hurricane, or a potential terrorist activity). Given the high degree of uncertainty regarding the timing, spread, and ultimate effects of COVID-19, and the associated continued turbulence on the health and economic fronts, this year every agency should consider this approach, detailing the trends and uncertainties they could face.

Uncertainty is the hallmark of the current moment. Some uncertainties will be common across federal agencies, such as:

- The severity and duration of the pandemic—How will the disease progress? Will there be multiple waves of infections?

- The health care system response to the crisis—Is there enough capacity to handle new cases? When will a vaccine become available?

- The economic consequences of the crisis—What will be the overall impact on GDP? Which industries and geographies will face the greatest economic losses?

- The level of social cohesion in response to the crisis—How will social isolation affect citizens’ mental and emotional well-being? Will civil unrest exacerbate divisions? Will Americans lose trust in the government?

- The willingness of individuals to maintain social distancing and the use of masks—Will consumer sentiments change over time? How long will it take for individuals to return to offices or resume traveling?

Other uncertainties will be more particular to individual agencies. For example, how will COVID-19 affect the number of visa applications to the U.S. Department of State? Or, through its impact on global energy demand and prices, how might COVID-19 impact the Department of Energy’s shift toward renewables? Or, for the U.S Department of Transportation and DHS, how long will different foreign borders be closed to US travelers?

This analysis should also explore additional missions or tasks created by the crisis; its impact on workforce, infrastructure, and budget; and any resources that might be sensitive to future disruptions.

Of course, even without the pandemic, the world is changing. It is therefore also important to identify COVID-19’s effect on key trends, whether new or changing due to the pandemic.

Accelerating and decelerating trends

COVID-19 has created major disruptions, causing some trends to accelerate while others have begun to decelerate. Some of the accelerated trends include:

- Digitization: Social distancing efforts have increased the adoption of contactless technologies and digital experiences, such as the rapid expansion of telehealth as an alternative to in-person medical appointments.6

- Growing reliance on e-commerce and home delivery: Due to the twin benefits of convenience and contactless services, COVID-19 has created a surge in online sales—the US e-commerce industry had grown 68% year over year by April 2020.7

- Increased virtualization of the workforce: Government agencies have quickly adapted to remote work. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, for example, quadrupled its telework capacity from 120,000 users before the pandemic to 500,000 users by May 2020.8

- Increased focus on health and safety: COVID-19 has brought health and safety to the forefront.

- Greater social responsibility: In response to the COVID-19 crisis, several private firms have engaged with governments to accelerate the availability of testing kits, N95 masks, respirators, and ventilators.9

- The emergence of pop-up ecosystems: Value chain disruption is likely to lead to more creative partnerships, such as Apple and Google collaborating to develop contact tracing software across their mobile platforms.10

- Increased surveillance: The urgent need to contain viral spread has increased citizens’ willingness to share data for value (e.g., mobile alerts for contact tracing). This will likely lead to enhanced surveillance among employers and governments. A recent Pew Research Center survey found that more than half of Americans (52%) feel it is somewhat acceptable for governments to track cellphone locations of people who have tested positive for COVID-19 to slow the spread of the virus.11

On the other hand, other trends are expected to slow or reverse in the wake of COVID-19 including:

- Slowdown in the sharing economy: Rising health concerns and virtual work have reduced demand for shared services and coworking spaces. In a recent survey, 54% of respondents in the United States said they plan to limit their use of ride-hailing services if COVID-19 continues to spread in their community.12

- Slowdown in urbanization: Social distancing and fear of contagion may deter people from living and working in densely populated cities. An April 2020 survey of more than 2,000 US urban dwellers found that 39% of them are considering leaving for less crowded places.13

- Less global movement of people: As of June 2020, around 65% of countries had completely sealed their borders to international tourism.14

- Setback to segments of the gig economy: While there has been a noticeable uptick in demand for freelance workers in specialized or higher-skilled fields such as algorithmic coding and statistical analysis, other jobs, such as nondelivery transportation and cleaning, have taken a hit. Demand for face-to-face gig work declined by a little over 35% across North America, Europe, and Asia during the second quarter of 2020.15

- Reduced globalization of supply chains: More protectionist policies may drive supply chains to be “brought home” to mitigate regional risks. The World Trade Organization expects a drop of anywhere between 13% and 32% in merchandise trade between countries in 2020.16

- Reduced congestion and improved air quality: Social distancing and the shift to telework have dramatically reduced road traffic, resulting in better air quality. In April 2020, daily global CO2 emissions fell by 17% on a year-over-year basis.17

Identifying the uncertainties is a key first step in developing strategic choices. The next step is to translate those uncertainties into different possible scenarios that capture the outcomes of various uncertainties.

Develop future scenarios

While it’s impossible to predict the future, scenarios offer a rich way to address uncertainty by considering a range of possible futures, examining how trends and uncertainties might interact, and anticipating likely sources of pressure. By providing clear insight into risks and opportunities, scenarios can help executives make informed decisions.

Scenarios are not new to government. The Department of Veterans Affairs used scenarios in developing its FY 2018–2024 strategic plan.18 The U.S. Coast Guard has long used scenarios as a basis for its strategic planning through Project Evergreen, including for Arctic mission activities.19 While scenarios have been primarily used for strategic planning, there is no reason they cannot be brought to bear on the transition process; indeed, the Center for Presidential Transition notes, “The process of preparing for a transition, particularly as it relates to assessing and communicating information on the entire agency and priority issues, can also serve as a foundation for the development of a new strategic plan by the incoming administration.”20

Traditionally, scenarios are associated with longer-term futures and truly disruptive black swan events. But near-term scenarios can also be useful in times of great uncertainty. In fact, when there is a change in administration, tabletop exercises, which are also referred to as scenarios, can promote operational continuity in the face of a disruptive event early in a presidency.

By providing clear insight into risks and opportunities, scenarios can help executives make informed decisions.

A view into different possible futures is useful not only to identify risks but also to assess the potential impact of such risks, as explained in the next section. Of course, each agency would want to build their scenarios around the critical uncertainties and key trends most impacting their organization. These might include first- or second-order COVID-19 forces, but they might also reflect other social, technological, environmental, or economic uncertainties.

Analyze implications for your organization

The next step is to consider the implications of these forces on your organization, either direct or indirect. The implications of individual trends and uncertainties should be identified, but the greatest impact typically occurs through forces working in concert as explored through scenarios.

The implications should be specific and focus on key areas such as agency operations, policy, budget, regulation, workforce, and procurement.

What will the acceleration in telehealth mean for Medicare, Medicaid, and military health? How might local policing reforms impact federal law enforcement agencies? When might city dwellers feel safe to return to public transit, and how will different timelines impact the Federal Transit Administration?

The implications should be specific and focus on key areas such as agency operations, policy, budget, regulation, workforce, and procurement (figure 2 is an example).

Determine strategic choices for action

The final step is to turn the implications into a set of strategic choices for action. To be sure, it is helpful to present new leaders with “here are some developing situations—and their implications—that you should be prepared to address.” Even more helpful, however, is to also present them with a choice of possible paths forward. This does not necessarily mean a course of action should be recommended. In fact, there are certain policy-related areas where the specific course of action is the purview of the White House or political appointees.

But even on difficult topics, it is productive to frame potential action choices as a starting point. The EPA in its issue paper template asked staff to: “Please provide potential options for moving forward that an incoming administration may consider when deciding its course of action on the issue. The purpose of this section is to help conceptualize different approaches that could be taken to address the decision or issue.”21

Transforming issues into choices is important for several reasons. First, research finds that making a choice between different possible courses of action produces better results than simply approving a single recommended course.22 Second, it can help to prevent the organization from cycling on pondering the issue—people questioning an issue’s importance, collecting more data, discussing it repeatedly, and so on. It is easy to keep discussing an issue unproductively without making real progress.

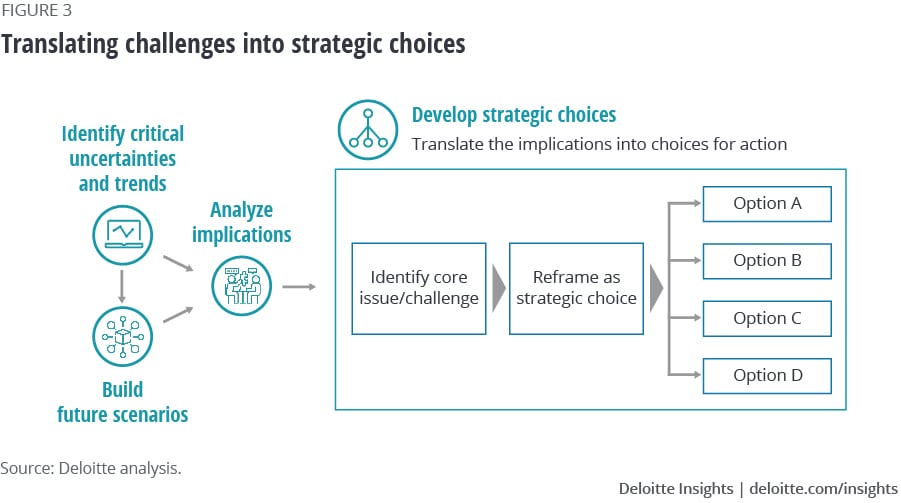

The act of reframing it as a choice can help to move the organization forward and shift the dialog to how best to decide on a course of action. The effectiveness of this approach has been demonstrated through “strategic choice structuring,” a framework developed by the Monitor Group (now Monitor Deloitte).23 It can serve as a foundational model for identifying dynamic and forward-looking possibilities (figure 3).

The groundwork done in identifying key trends, developing scenarios, and analyzing the implications will help agencies reframe the specific issues and challenges into options.

The groundwork done in identifying key trends, developing scenarios, and analyzing the implications will help agencies then reframe the specific issues and challenges into options.

Step 1: Identify the specific issues and challenges

Thinking through the trends and uncertainties, the way they interact through scenarios, and their implications for the organization should lay the groundwork for crystallizing the core issues and challenges that must be addressed. While many agencies are affected by common pandemic-related trends, they can manifest as different core challenges for different agencies. For some, addressing specific backlogs while being unable to operate at full capacity due to distancing may be the dominant concern. For another, it may be accounting for the stimulus funds that have been dispersed (perhaps while also being unable to work at full capacity levels). Being clear about the problem serves to guide consideration of potential solutions.

Step 2: Reframe the issues and challenges into crystallized strategic choices

Once challenges are identified, it is important to reframe the concern, which is something passive, into a choice, which is something active. This step asks the organization to strip the issue into the fundamental choices that could address the challenge. As noted earlier, this can help the organization and incoming leadership get “unstuck” from the issue and make better decisions.

Step 3: Articulate possible options

While a crystallized high-level choice is powerful in helping an organization move from challenges to choices, the choices aren’t really ready to be investigated and selected until they are better articulated as possible paths forward. Turning the basic choice into an array of plausible options is the final step to laying a foundation for new leadership to “hit the ground running.” In the current COVID-19 situation, this three-step process is likely to be somewhat iterative as new ground is explored and innovative solutions may become possible.

The DHS 2016–2017 Arctic security priority-issue presidential transition white paper can be summarized using the framework outlined in this paper as shown in figure 4. This example is shown here to illustrate both the steps in the process and the logic that ties them together.

Preparing the new leaders

The upcoming presidential election will have a rare backdrop of twin crises on the health and economic fronts. Agency executives will need to navigate these turbulent times and adequately prepare leadership, whether new or returning, to make informed choices.

Agency leaders, as they prepare their materials to educate a possible incoming or returning administration, should take the opportunity to lay out the uncertainties, issues, and strategic choices after the election.

More on COVID-19 and the public sector

-

Behavior-first government transformation Article4 years ago

-

How governments can navigate a disrupted world Article4 years ago

-

Seven strategies to limit fraud, waste, and abuse of COVID-19 relief dollars Article4 years ago

-

Transforming government post–COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the virtualization of government Article5 years ago

-

Governments’ response to COVID-19 Article5 years ago