Bike commuting has been saved

Bike commuting Part of the "Smart mobility" research report

19 May 2015

The number of potential commuters in America’s metropolitan areas who could bike to work with relative ease is much higher than one might expect.

Bike commuting: Unleashing its economic, health, and safety benefits

Any American who visits European cities such as Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Stockholm cannot help but marvel at the thousands of bike commuters streaming past them on the morning commute, in all types of weather. In these cities, up to half of all commuters bike to work each day, more than those who drive or take public transport.1

The story is very different in the United States, of course. Only 0.6 percent of commuters currently bike to work in the urban areas we study here. The good news is that bike commuting in America is growing by about 7.5 percent annually.2

Even so, given such low participation rates, it’s unsurprising that biking is far from the top of the list of transportation planners’ congestion reduction strategies. After all, most communities lack good biking infrastructure, and US commutes tend to be longer than those in other nations, which can discourage bike commuters.3 Our pervasive car culture also makes persuading Americans to give up the comfort of their cars daunting.

That said, the number of potential commuters in America’s metropolitan areas who could bike to work with relative ease is much higher than one might expect. A recent MIT analysis of several large cities, including Washington, DC, Philadelphia, and San Francisco, indicates that biking would be the fastest way to reach large portions of each city’s areas during rush hour.4

The economic potential of bike commuting

To estimate the potential economic returns of increased bike commuting, we created a geospatial model based on the assumption that anyone who works five or fewer miles from home could reasonably commute by bike, at least sometimes, given improved infrastructure, better commuter benefits, and sufficient societal encouragement. We chose five miles because that distance comprises 75 percent of all bike trips from the most recent nationally representative survey of commuting patterns.5 We reduced our projections to account for well-known determinants of bike commuting frequency such as trip-chaining, weather, and climate (for details of our modeling techniques, see appendix B).

Based on these assumptions, we estimate that a little less than a quarter of current commuters (28.3 million out of 108.4 million) could switch to bike commuting as one of their main modes of commuting if barriers to biking were substantially reduced. To be sure, an increase of this magnitude won’t happen anytime soon in America, but even much smaller increases would have large impacts on traffic congestion and health and wellness.

According to our analysis, the economic potential from increased bicycle commuting is almost as high as that from increased ridesharing. The potential annual VMT reduction from new bikers (13.1 billion VMT) would amount to almost 1/2 of 1 percent of all vehicle miles driven last year (2,950,402 million), according to the Federal Highway Administration. (see figure 4).

We recognize that few, if any, bike commuters will bike to work every day of the year. In fact, hours of daylight, weather, and climate will keep many from cycling as far or as often. We therefore apply a conservative annual frequency factor of 96 days per year to arrive at our predicted total mobility savings from biking of $27.6 billion.

As with our projections of savings from increased rideshare, projected bike commuting savings will come from several sources. New bike commuters would reap direct benefits of $7.7 billion through fuel savings and reduced vehicle ownership costs. Taking more cars off the road would benefit commuters nationwide, who stand to reap $17.1 billion in indirect savings due to reduced congestion-related fuel and time wastage. Cities stand to gain $2.6 billion annually in indirect savings based on lower road construction costs, reduced accidents, and lower carbon dioxide emissions (see appendix B for details of savings calculations).

Figure 4 shows the potential savings from increased bike commuting for the 10 largest metro areas in terms of number of potential new bike commuters.

It’s important to again underscore that these figures represent an idealized future state, a theoretical ceiling we could reach with improved biking infrastructure, technological changes, and societal forces that promote bike commuting. The barriers to bike commuting are substantially different from those affecting other alternate forms of transportation. We’ve already mentioned distance, climate, weather, and trip-chaining. Other factors that potential bike commuters often cite as keeping them out of the saddle include perceived and actual safety considerations, lack of dedicated bike lanes and infrastructure, fear of traffic, lack of daylight, and inconvenience.6

Bike commuting potential in Fairfax County, VA

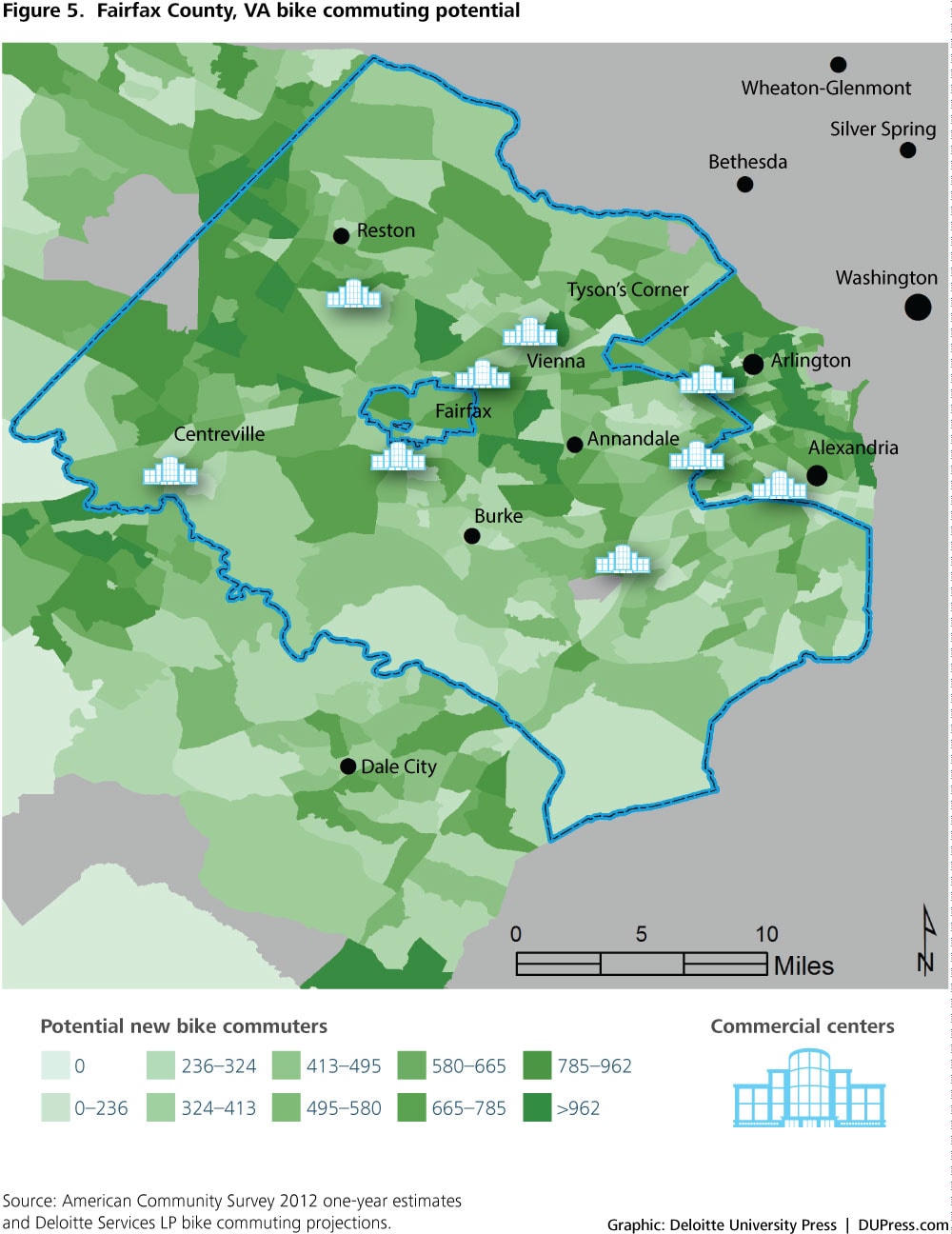

The map in figure 5 shows bike commuting potential in Fairfax County, VA, located just outside of Washington DC; darker shades indicate areas with greater potential.

The areas with higher concentrations of potential bike commuters cluster around suburban “edge cities” containing commercial centers such as Reston, Tysons Corner, Herndon, Manassas, and Woodbridge. The identity of some of the “hot spots” may be counterintuitive, particularly Tysons Corner, which used to be a national symbol of car-friendly and congested development. But these areas are typical of what we found in our nationwide study, and “bikeability” now forms a major part of Tysons Corner’s long-term development plan.7

Medium-density suburban neighborhoods located one to three miles away from thriving commercial developments offer surprisingly good opportunities for increasing bike ridership. Further down the I-267 Dulles Tollway is Reston Town Center, another car-friendly suburb that has begun planning for 13 bikeshare stations to sustain its economic growth and attract younger residents.8

Which neighborhoods offer the greatest potential?

Bike commuting’s potential value is not evenly distributed inside each metro area. The greatest potential benefits are likely to be in core urban centers and, perhaps surprisingly, in suburban neighborhoods near smaller commercial centers (see sidebar, “Bike commuting potential in Fairfax County, VA”).

Nine ways to accelerate bike commuting

Our research suggests nine ways in which cities can align incentives to accelerate the growth of bike commuting.

- Invest in bike infrastructure. The biggest barrier to increased bike commuting in America is road safety.9 Some European cities have addressed this problem in innovative ways. In Copenhagen, for instance, biker safety has increased significantly due to improvements in biking infrastructure, such as intersections with dedicated bicycle traffic lights, wider bike lanes in congested areas, and a comprehensive regional bike planning approach that ties the whole network of bike lanes together across municipalities.10Increasing bike safety requires investments in biking infrastructure. Continual small improvements in this infrastructure are one of the main factors contributing to bike commuting’s slow but steady growth.11 And, fortunately, a little funding can go a long way. One nationwide 2013 survey found that even the most expensive bike infrastructure costs an order of magnitude less than many roadway upgrades. For example, the average cost of a mile of bike lane is $133,170, compared with an estimated cost of $2.5 million per lane-mile for roadways.12 The first phase of Reston Town Center’s bikeshare project, including bicycles, stations, operations, and maintenance, will cost $1.2 million, some to be contributed by private partners. Cities can carry out such improvements piecemeal, without the multimillion-dollar financing packages required for other transportation infrastructure. The return on investment (ROI) for bike infrastructure improvements, moreover, is comparatively high. In 2013, for example, the Pedestrian and Bike Institute estimated that building one mile of new bike lane at a cost of $133,000 in an area of medium residential density such as Washington, DC could increase bike commuting by 30 percent.13

- Build smart biking infrastructure. As they construct new signage, bike lanes, and traffic signals, cities should also take advantage of emerging technologies to improve their biking infrastructure. In 2013, the city of Chicago announced it would begin using micro-radar to count passing cyclists on some of its transportation routes to improve its transportation planning.14 Arlington, VA uses real-time bike counters on several of its trails.15 In Copenhagen, LED lights have been embedded in the pavement to alert cyclists to maintain their speed; this helps them catch green lights at upcoming intersections. Currently in development are sensors that could detect groups of cyclists riding together and keep intersection lights green longer.16

- Encourage bikesharing programs. Economists and planners know that there’s a tipping point for transportation safety. As more new bikers join, safety—and the perception of safety—improves for all. Growing numbers of bikeshare stations can encourage enough new bikers to start riding in an area to jumpstart this virtuous cycle. For those who haven’t tried them, bikeshares are programs where members and casual users can rent bikes by the hour, picking them up and dropping them off at convenient bikeshare stations around the city. The community-building effect of bikesharing has been observed in Portland, OR, Chicago, and Washington DC, and is beginning to materialize in suburban satellite communities as well.17

- Create PPPs to fund infrastructure improvements. PPPs can fund infrastructure improvements and generate new demand. Alta Bikeshare, the commercial partner of Washington DC’s Capital Bikeshare, had 567,997 total members as of November 2014, with membership growth of around 2 percent monthly.18 Alta Bikeshare plans to partner with Fairfax County, VA and Reston-area developers to bring 13 bikeshare stations to Reston Town Center.19 Social impact bonds, described earlier in this paper, could be used to provide additional incentives for innovation within such PPPs.

- Build biking infrastructure where it can have the biggest impact. Studies of numbers of potential new bike commuters, such as this one, can help determine where investments in new bike infrastructure should be made. Communities should consider physical and geographic factors such as the number of parallel direct routes to a centralized business district (which facilitate new bike routes) or the presence of large highways transecting bike corridors (which hamper flows). Micro-targeting outreach efforts to such neighborhoods can help maximize the growth of bike commuting. Similarly, households with fewer vehicles or fewer drivers, as well as commuters who rent their homes, show a greater preference for biking.20 Geographic variations are important to understand as well; the West and Midwest have higher biking rates than the South and Northeast.21 Geographic variation includes both cultural factors and weather. In fact, climate has a weak relationship with biking patterns, according to the Alliance for Biking and Walking, which finds that excessive heat, cold, and rainfall only slightly deters some bike commuters.22 The German city of Wiesbaden provides an ingenious way to ensure that bike paths are built where they’re most needed. As cyclists pedal around city streets, an app traces each route they take and adds it to a huge crowdsourced map of proposed bike paths in the city.23 Data from the thousands of bike rides is aggregated onto the map, which shows the most popular routes.

- Develop regional bike plans. Most of the 79 cities examined in this study have municipal biking plans, but few have regional biking plans extending across the metropolitan region. Salt Lake County is an exception, encouraging bike commuting through a regional transportation plan that connects cities within the contiguous metropolitan area. Salt Lake County’s plan is intended to ensure that roads and trails throughout the region connect sensibly, so that bikers can commute reliably and without disruption as they pass through different jurisdictions. This makes sense not only in terms of the plan’s expected environmental and public health impacts, but in economic terms as well. For the cost of a single interstate overpass, Salt Lake County estimates it can instead build out a comprehensive, integrated active transportation system that spans the entire county.24 In so doing, metro areas like Salt Lake County are building on academic research showing that cyclists are encouraged to bike more when infrastructure is continuous.25

- Link bike commuting to public health. Governments can promote bike commuting by linking it explicitly to health outcomes in outreach efforts to private citizens and to employers. For individuals, governments can highlight a demonstrated correlation between bike commuting and health. A study of Danish adults, for instance, shows that cycling to work lowers mortality rates by 28 percent after normalizing for differences in occupation, smoking, leisure time activities, and body mass index.26 When the audience is employers, governments can highlight health insurance savings for companies that promote bike commuting. One Minneapolis company offering financial incentives to employees who commute by bike found that its health insurance costs during the trial period fell by 4.4 percent.27 The UK government and business community is promoting biking initiatives through a cycle-to-work scheme. The initiative allows employers to loan bicycles and related accessories to employees as a tax-free benefit that saves employees 42 percent on associated costs.28

- Use big data to encourage bike commuting. In the future, personal mobility data will feed into central statistical databases that will be used to track citywide progress in health, commuting efficiency, and trail conditions. Anonymized biking data from both public and corporate repositories will improve overall bike planning and provide incentives to the private sector to support more biking. Strava, an app used to track cycling activity, is a good example. Strava allows bikers to upload GPS data about their bike rides to a central portal where they can compare their distances and speeds with other cyclists’ training regimens. In the process, a new trove of geospatial data is collected that can allow transportation planners to see which bike trails are most popular.29 Similarly, the “Copenhagen Wheel” partnership between the city of Copenhagen and the MIT Media Lab is collecting anonymized data on bike commuters’ speed and distance and combining it to disseminate real-time information on bikeway conditions to all riders.30

- Expand tax incentives to encourage bikesharing and bike commuting. The federal Bicycle Commuting Act of 2008 allowed employers to deduct up to $20 per employee from their own taxable incomes when offering bike commuting benefits. This is a useful start, but one that compares poorly to the $115 per employee deductible available for transit benefits.31 Extending greater pre-tax benefits to bikesharing and bike commuting programs could increase its appeal to employers.

Explore our collection of research on smart mobility at the links below.

- Key findings from the smart mobility study

- The promise of smart mobility

- Ridesharing

- Bike commuting

- Carsharing

- On-demand ride services

- Alternative transportation atlas (interactive map)

- Impact by metropolitan area (interactive table)

- FULL REPORT—Smart mobility: Reducing congestion and fostering faster, greener, and cheaper transportation options