Smart Refugee Resettlement Using technology to transform the resettlement process

14 minute read

13 January 2021

The refugee resettlement process is often hampered by fragmented information, as cases are handed from one agency to another. A single smart platform for the data could help address this problem.

Key messages

Introduction

Today, there are an estimated 79.5 million forcibly displaced people and 26 million refugees worldwide, the highest numbers on record.1 Ongoing global challenges such as public health emergencies, including the COVID-19 pandemic, can exacerbate challenges for these populations, such as the availability of adequate resources in refugee camps.2 The US refugee resettlement process can take an average of 18 to 24 months from the refugees’ initial referral by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) to their arrival in the United States, with wait times expected to only increase.3 Once in the United States, refugees can face difficulties finding affordable housing, medical care, and stable employment, and integrating into their new communities. While resettlement services are provided at the state and local levels by federally funded nonprofit organizations, when government stakeholders and case managers lack the necessary data and tools to help refugees address these challenges effectively, it can deter refugees from accessing these services.

Learn more

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

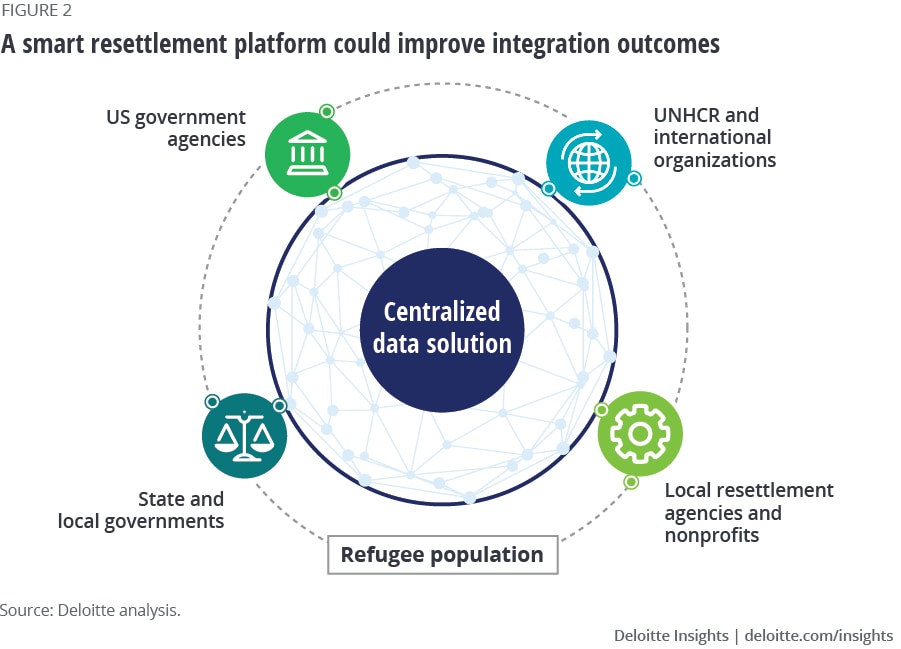

One approach to addressing many of the data-related challenges with resettlement could be a smart resettlement platform. Such an integrated data platform could help connect key stakeholders, reduce application processing time, increase data security, and improve integration and resettlement outcomes.

A smart resettlement solution is based on three pillars, corresponding to three main stages of a refugee’s resettlement:

- Application—Creating a secure online way to enter a refugee’s data into the platform, including all the important identification information and credentials that key stakeholders will need to access later.

- Placement—Leveraging available application information and data analytics to select the geography most conducive to each refugee’s integration.

- Integration—Leveraging refugee profile information to suggest relevant housing, employment, and education opportunities, and storing relevant information to help the case worker provide the refugee with access to critical services such as health care, employment, and cultural orientation.

With a smart resettlement solution, international organizations and national, state, and local resettlement agencies can improve the efficiency of their resettlement services, as well as focus on long-term integration issues related to mental health, underemployment, and prejudice, to help refugees become full-fledged members of their new communities.

An overview of the current US resettlement process

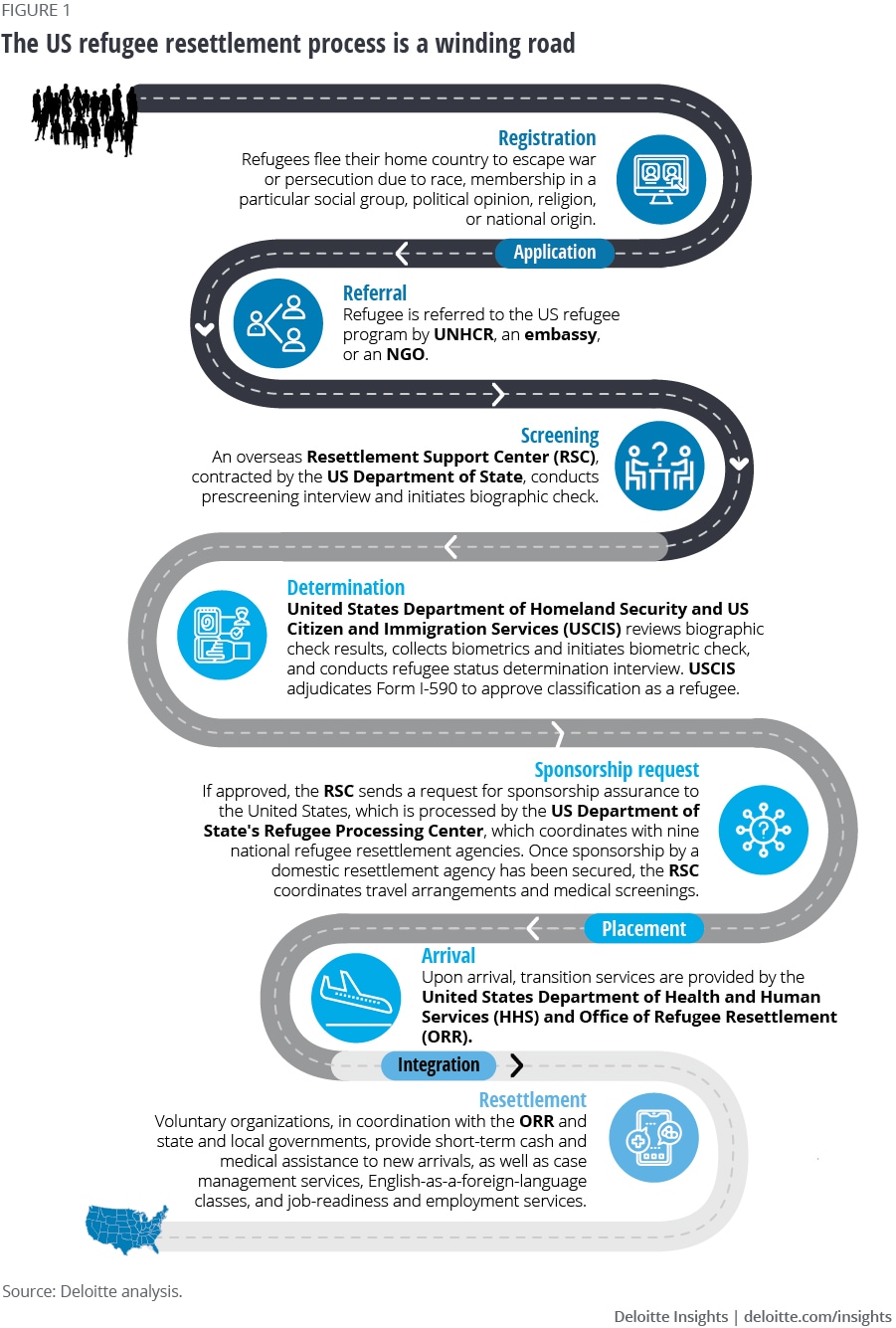

The US resettlement process can be lengthy and complex, with multiple stakeholders providing varying levels of support at different stages (figure 1). Stakeholders include the International Organization for Migration, US Department of State, the Department of Homeland Security, US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS), UNHCR, state and local governments, and many voluntary organizations that support and resettle refugees. With such a large community of organizations, the resettlement process can be costly, time-consuming, and disorganized, leading to inefficiencies.

Each organization has its own software or systems to monitor its area of responsibility in the resettlement process, which can create challenges with sharing information across systems. In some cases, the number of users from nongovernment resettlement organizations exceeds the capacity of the network’s technical systems, creating further delays in transmitting and analyzing data. The average processing time from refugees’ initial UNHCR referral to their arrival in the United States is approximately two years.With the incoming Biden administration's goal to raise the refugee admissions cap to 125,000 in the United States, centralized processes are imperative.4

In some cases, the number of users from nongovernment resettlement organizations exceeds the capacity of the network’s technical systems, creating further delays in transmitting and analyzing data.

Refugee resettlement stakeholders can face several challenges

Resource constraints

Decreased refugee quotas in the United States have forced many refugee resettlement agencies to reduce operations and lay off employees. While quota numbers have fallen, these organizations can support refugees in assimilation efforts for up to five years following initial resettlement, resulting in high demand for services across the offices that remain operational.5 A common, more efficient platform would result in less time spent in supporting administrative efforts and more time helping refugees assimilate. For example, over the past few years, Catholic Charities USA has been downsized to 50 offices from more than 60, and the International Rescue Committee to 25 from 28. Another refugee resettlement agency, Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, laid off about 100 employees nationwide, further straining resources.6

Lack of coordination

Strategic coordination and communication across organizations providing services is often lacking, and efforts can be reactive and duplicative. The issue may be further exacerbated by resource constraints and underutilized data and technology with limited data standardization and security capabilities.7 For example, federal agencies, state agencies, and resettlement organizations are responsible for different facets of the refugee process. When these participating agencies do not always adequately share information and coordinate their activities effectively, it can further strain the resettlement process.8

Underutilized data and technology

The current resettlement process is generally based on siloed, outdated technologies or manual processes that can slow down the resettlement process, leaving refugees vulnerable in host countries or while in detainment. There is often a lack of coordination and information-sharing, making it difficult for advisers and refugees to refer to some tools and databases. Access to systems from overseas, nongovernment-affiliated websites, and manual spreadsheets at multiple levels pose an additional challenge. When these technologies fail to work together, it’s difficult to maximize benefits for refugees and support stakeholders.9 Many smaller refugee resettlement agencies cannot afford to upgrade their technology and are left operating with vulnerable systems.10

Public misconceptions

Public reaction to resettlement policy limits the effectiveness of the resettlement process and is most often shaped by fear rather than facts. For instance, the recent COVID-19 crisis has resulted in travel and immigration restrictions to address fears of widescale disease spread.11 Historically, migrants and refugees have been made scapegoats during public health emergencies, especially with regard to infectious disease transmission and spread.12 These misconceptions tend to stem from lack of data, weak public communication, and limited services available to support local communities and integrate these into the resettlement process.13 Instead, resettlement initiatives can help to advance US national security measures by supporting the stability of global allies or partner agencies struggling to accommodate refugees.14

Fragmentation of information impacts every stage of a refugee’s journey, which we have broadly categorized as application, placement, and integration. We look at each stage in detail in the remainder of this article.

Application

In most cases, UNHCR helps to manage the initial registration process and issues identification documentation through its own data system (used in numerous countries with more than 500 distinct databases globally15) as well as a biometrics information system. This information is utilized primarily as a method of identification by other UN agencies, donors, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and the private sector; however, it can also be used to assist the application and screening process.16 For example, stakeholders such as the HHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention draft refugee health guidelines, and the International Organization for Migration conducts medical screenings to help ensure no inadmissible health-related condition exists.17 This would help agencies confirm that refugees entering the United States have a clean bill of health as well as track and trace where they have been prior to entering the United States to make informed placement decisions and better anticipate any potential health issues, such as contracting COVID-19. Additionally, once the biometric and biographical data is available and a determination has been made on the individual's status, then screening information can be streamlined between government agencies such as UNHCR, DHS, and resettlement support centers using a centralized platform.

Placement

In the absence of an established common platform to help place refugees, US refugee resettlement case workers must sometimes make resettlement decisions based on capacity availability. For example, case workers may have insufficient technology to collect, analyze, and review historical data to match refugees’ skill sets and needs profiles with the appropriate US localities as they enter the country. This can result in refugees being placed in the first available location, rather than a location that would better suit refugees and their family.

A smart resettlement platform can provide recommendations on employment placement by matching refugees with employment demand based on their skill sets and credentials, as well as filtering only those employers with the ability to hire refugee populations. Without this information, advanced credentials can be overlooked, hindering refugees’ consideration for high-skilled work for which they may be qualified.18 For example, sometimes refugees with in-demand skills, such as teachers, health care professionals, or engineers, are unemployed or underemployed and may be placed in lower-skilled roles, leading to underutilization of labor supply. Case managers can often only provide limited assistance in navigating the job market. Instead, refugees may be left to rely on social networks or resettlement agencies to which employers might reach out with vacancies.19

This mismatch of skills and needs represents a great opportunity loss for both refugees and their new community, especially as many communities across the United States are in desperate need of skilled and unskilled labor. Refugees sharing their skills only helps to strengthen their integration within the community.

Integration

Once a placement decision is made, finding housing, health care, employment, and education opportunities becomes the next challenge that local governments and volunteer organizations must help with. The current US process for resettling refugees is divided among nine refugee resettlement agencies, which are often given two weeks or less to find potential housing providers.20 In this short period of time, their staff needs to identify and secure affordable quality housing prior to a refugee’s arrival. This process is often manual, with case managers spending hours to find suitable housing for newly arrived refugees. The significant time spent on identifying housing can prevent the case managers from providing higher-touch services that support positive integration outcomes, such as identifying employment opportunities.

A smart resettlement platform

If fragmentation and lack of data are at the root of these challenges, then a centralized platform can help address them by enabling better sharing of data. A smart resettlement platform offers such an approach. It works by integrating data across numerous support areas and organizations in a centralized hub to effectively analyze refugee data and share tailored resettlement options for refugees, including location, employment, education, health care, and housing. It’s also likely to save significant financial resources for refugee resettlement organizations that no longer have to spend hours digging through data, searching for homes, and finding jobs. This would allow these organizations to focus on core operational and long-term services, such as mental health and community integration. The platform would also enable government and resettlement agencies to act quickly in times of crisis such as economic collapse, natural disasters, or pandemics. It would ultimately enable powerful data-driven adjudication, streamlined health and security screening and vetting, and efficient placement decisions to provide refugees and their families with an appropriate resettlement, enabling a positive integration outcome for their new communities.

Resettlement organizations are making progress in identifying efficiencies and building platforms and tools to better manage migration data. One example of a solution under development is UNHCR’s Population Registration and Identity Management EcoSystem platform.21 Another is Annie Moore (Matching and Outcome Optimization for Refugee Empowerment), an information-sharing platform that is used predominately by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. This software helps place refugees in suitable homes based on prior employment, language support, and nationality.22

A gap exists in the US resettlement ecosystem when it comes to effectively linking information to deliver services to refugees across the three pillars of application, placement, and resettlement. However, there are numerous technical enhancements that can be made across these pillars to provide a stronger, more efficient, and more secure centralized data platform solution.

Application

For the application process, a centralized hub of secure identification data can be stored and accessed by key stakeholders to enable streamlined communication of data between government and nongovernmental agencies such as UNHCR, US Department of State, and DHS. Agencies can learn from, and build upon, current technologies as a starting point to develop a smart resettlement platform, while using other technologies such as Annie Moore, process robotics, or other artificial intelligence to augment the solution. Process robotics, in particular, could aid the resettlement process by eliminating repetitive, manual, and time-consuming work, providing employees more time to focus their energy on higher-value tasks. Process robotics can help improve data accuracy by 99.9%, free up work hours, reduce transactional costs, improve processing times, and increase the availability of data.

Placement

Placement decisions could be made more effectively by leveraging predictive analytics to forecast anticipated areas of resettlement, including areas with emerging job openings or housing availability. Stanford University’s Immigration Policy Lab’s placement algorithm offers an example of predictive analytics.23 Utilizing tools such as this coupled with housing algorithms can strengthen placement decisions and, through productive employment, help refugees develop stronger positive relationships with their local communities while reducing misconceptions of refugees entering the workforce—ultimately helping to improve resettlement and integration outcomes for the refugee.

Integration

To find individual refugee resources at a local level, refugee resettlement agencies use a variety of mapping and housing technologies. For instance, the organization USAHello partnered with UNHCR to expand their FindHello application, which uses a mapping tool to help refugees locate resources such as housing, food, health care, and jobs in their local area.24 By connecting these technical tools through a centralized data platform (figure 2), refugee resettlement agencies can share and access information, working together to help ease pain points in the resettlement process, improve operations, and better resettle refugees.

How would a smart resettlement platform work in action?

Imagine a group of refugee families have just reached a UNHCR resettlement camp. Among them, a teacher and his daughter, a special-needs child, are referred to the US Refugee Program. They answer questions about their circumstances, provide documentation, and begin the process of attaining refugee status and resettlement in the United States. How might a smart resettlement solution work in their resettlement process?

Application

During initial intake to the US refugee program, UNHCR and the US Department of State collect various pieces of information such as biometrics, biographical and medical screening data, and information on countries of origin and travel that would be entered into the smart resettlement platform. This information could be referred to in times of national crisis for local interagency support, and to help lighten the lift for public health tracking and tracing efforts. All of the information is passed on to the refugee officer for adjudication, and the refugee is granted refugee status. The information gathered during the interviews would be available securely to need-to-know stakeholders at each stage of the process to inform refugee status and placement decisions, potentially expediting screening checks while ensuring appropriate data accesses are followed. After interviews and applications are reviewed, the teacher and his child undergo health screenings, which are expedited by the information already entered in the smart resettlement platform. This piece of the platform could leverage technology to provide the refugee with an established profile, including an identity that is recognized by all stakeholders, even if the refugee no longer has appropriate documentation.25

Placement

Once the teacher and his child are screened, agencies decide where to resettle the family based on an algorithm. This algorithm identifies a local community with a need for teachers rather than which resettlement partner has availability at that time. The platform confirms that the placement locality meets both the employment needs of the teacher and the health care needs of the child. Education or relevant qualifications are also considered and easily translated between states that are utilizing the smart resettlement platform. A resettlement agency case manager then reviews and validates the top recommendations from the platform to determine placement decisions that are best suited for the family. Additionally, a refugee workplace inclusion toolkit, similar to those proposed by the Tent Foundation, is provided to the teacher; it explains the process to be recertified as an educator and points to relevant resources that can help accelerate the teacher’s ability to practice in his resettled city.26 In times of crisis, case managers would use the smart resettlement platform to pull tracking and tracing data that would help them to better support local refugees. For example, in the COVID-19 pandemic, case managers could filter refugee populations based on age, health, or country of origin to identify resources that would be best suited for those families and communities.

Integration

Before the family arrives in its new community, the smart resettlement platform supports the case worker by providing potential housing, health care, and education opportunities for the family. Using technology similar to the FindHello tool, it automatically suggests three housing options that are available and large enough to house the family. Additionally, the platform identifies a school district with a job opening for a teacher that matches the refugee’s credentials. The case manager can then work with the local school system to place the child in the appropriate special-needs classes and connect the family with local community support services (including churches, synagogues, or mosques). These resources can also help pull health insurance plan information from HealthCare.gov (where refugees can navigate health care access under the Affordable Care Act) and provide options for refugees based on their information entered in the system. As the family settles into the community, the platform can share information on various programs designed to help integrate it into the new home.

This example illustrates how a smart resettlement platform leveraging innovative technical capabilities enables an efficient flow of data from the refugees’ initial interview through resettlement into their new home.

Getting started

Using a smart resettlement platform, the quality of resettlement would likely be significantly higher for not only the refugees themselves but also NGOs, government organizations, and external stakeholders, while enabling greater cost-effectiveness and efficiency for everyone involved. A smart resettlement platform can be the primary data source during national crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and help to provide health resources and communications to refugees. It could also be used for quick data pulls on refugee populations and areas of origin to inform local outreach efforts to support these populations that may be more vulnerable during emergency situations. In thinking through implementation of such a solution, organizations can begin making strides with their own systems by focusing on technology modernization efforts.

A smart resettlement platform can be the primary data source during national crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and help to provide health resources and communications to refugees.

Start with where you are

Attempts to create an ideal blue-sky process can quickly get bogged down in the nuts and bolts of change, without capitalizing on ongoing technological advancement. Taking an inventory of the current databases, flows, and systems across an agency and comparing it against other stakeholder systems is a place to start in planning for future integration efforts. This ability to integrate disparate databases and systems could significantly improve overall resettlement operations with less disruption to current operations.

Leverage existing tools

Using existing tools can speed the adoption of a smart resettlement platform because at least some stakeholders will already be familiar with them.27 Additionally, organizations would not need to dedicate resources for installation of, and training on, new technology, software, data systems, or other IT infrastructure.

Aim for open communication

Increased transparency and dialogue among stakeholders are critical to meeting the needs of refugee populations and all resettlement organizations. Additionally, open communication is imperative to minimizing disruption to current operations and processes. Increased buy-in through stakeholder engagement would enable an interoperable centralized environment for the US refugee resettlement process.

A smart resettlement platform would help service providers be more streamlined and connected. Enhanced data security and data-sharing practices would reduce processing times; automating administrative tasks and utilizing housing and job placement tools would help improve integration and resettlement outcomes. With enhanced technological tools and dedication across stakeholders, a smart resettlement platform could lead to higher-quality integration outcomes for refugees, government agencies, and local communities.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more from Government & Public Services

-

The future of work in health and human services Article4 years ago

-

The Nordic social welfare model Article4 years ago

-

Government backlog reduction Article5 years ago

-

Cocreation for impact Article5 years ago

-

Customer experience in government Collection

-

Government & Public Services Collection