Rebuilding a stronger digital society How can data-driven businesses deliver greater value to users, customers, and society?

17 minute read

17 June 2020

Data has never been more valuable—or more fraught. In a time of turmoil and uncertainty, how can businesses and people come together to create shared principles for society and a better data-driven future for everyone?

Billions of digital footprints

The COVID-19 crisis has cast the data dilemma into stark contrast. Ready access to information about people, populations, and epidemiology can aid containment of pandemics and speed pathways to treatment and vaccination, literally saving lives. At the same time, communicating such data can expose personal information, jeopardize societal freedoms, and potentially arm authoritarians with more power. The high-stakes and perhaps sensational nature of such considerations often casts the debate into an us-versus-them narrative poised between salvation and ruin. Ultimately, the trust between all parties can suffer.

Learn more

Explore the Telecom, media & entertainment collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

And yet the crisis can be an opportunity for companies to illustrate the value of sharing data, and to do so with the input of users, customers, and governments. Deloitte’s own work with ConvergeHEALTH Connect1 brings together messaging platforms, cloud leaders, CRM providers, health care systems, and governments to help enable rapid triage of populations for possible contagion. The effort was enabled by strong collaboration across multiple stakeholders willing to share data toward greater outcomes, and it is one among many examples that show how better management of personal data can tackle some of the largest challenges facing humanity.

Key takeaways

As more companies stake their future on access to data, consumers are becoming more mature in understanding how their data is being used—and are making louder demands for regulatory oversight and constraint. People interact with data collection in any number of ways, but the high public profile of top social media and messaging services means that these businesses are often challenged to address issues of data privacy, security, and transparency.

Social media and messaging services also have a great opportunity to get ahead of regulators and establish greater trust by reining in advertising exchange networks and data brokers—the opaque ecosystems of third parties that aggregate and sell data. Perhaps even greater is the opportunity for all data-driven businesses to deliver more tangible value directly to the customers and users who are providing the data. But such efforts may require competitors to collaborate and diverse industries to align on the greater benefits available to their businesses, their customers, and society in general.

Companies, regulators, and consumers have long debated issues of responsible use of data, but the COVID-19 crisis has underscored the central role of data-driven organizations while pushing aside some of the obstacles blocking their evolution.2 In the early years of the 21st century, it has become apparent that our collective futures will very likely be more data-driven, so it may be imperative that we embrace that fact and design the best future together. It is entirely possible to have a robust data-driven world that defends privacy, reinforces trust, and distributes value equitably.

Half of humanity has access to the internet, and more than 3 billion people now have smartphones.3 Numerous mechanisms work to identify consumers, follow their digital footprints, deliver better experiences to them, and connect them with businesses. These mechanisms also feed a marketing and advertising economy geared around gaining more granular views of the consumers they are trying to reach. But the cost has been high: The mechanisms of collecting and leveraging consumer data have enabled fraud, influence campaigns, and geopolitical manipulation.4

The questions are large: In a time of great turmoil and uncertainty, how can businesses and people come together to create a better data-driven future for everyone? How can they agree on shared principles for society? And how can they use data to create greater value and transparency, accelerating economic recovery while laying new foundations for a thriving future?

A maturing digital society

Technologies are often neutral until wielded by people—and billions of users have brought forth a wide range of societal effects. The top free-to-use social media and messaging services have the largest surface area of consumer data collection, where people have shared their behaviors and interactions in exchange for the value they receive. These services tap into something innate about humanity and our eagerness to connect and share; they have enabled people across the globe to rapidly organize, collaborate, and innovate, laying the connective tissue of our young digital society, for both good and ill. After nearly two decades of use, social media and messaging services are coming under greater scrutiny from users who are more aware of how their data is driving opaque markets, and from governments wrestling with some of the darker consequences of a digital society that has become highly programmable.5

More people can see how their behaviors on digital platforms are being captured, used, and shared—and ever more view the value they get from this deal as inadequate.6 Their trust in data-driven consumer services has declined, with more sensing that the greater advantage is to businesses, advertisers, and unknown third parties.

- Sixty percent of American adults do not think they can go through daily life without having data collected about them.7

- Eighty-one percent say that the potential risks they face because of data collection by companies outweigh the benefits.8

- Deloitte’s 2019 Connectivity and Mobile Trends Survey found that 72% of consumers agreed that they were more aware of how their data is collected and used than they were a year previous.9 And yet the most common action they said they take to ensure their own privacy is turning off location-based services; 40% have done so, while only 15% stopped using a social media service entirely.

- Only a quarter claimed to always or often read privacy policies before agreeing to them, and 63% said they understand little to nothing about current data privacy laws and regulations.10

Consumers are maturing and more are showing early changes in behavior. But many don’t fully understand data use and privacy, and most may not grasp the scale of third-party access to their data. With more legislators taking on these businesses, the early implementations of these services may need rebalancing.

The top social media and messaging services are maturing as well. They have grown to become some of history’s largest companies, wielding enormous capital to deliver value to users while reinforcing their lines of business. Business leaders are aware of the challenges brought by their scale, tackling the herculean task of maintaining free services for billions of people across a global patchwork of markets and regulatory regimes, while defending businesses that malicious third parties are increasingly trying to hijack.11

More are implementing new privacy and transparency tools and giving users more control over privacy preferences.12 They are rethinking how to handle third-party data sharing and calling for smart regulation and oversight while extending the protections afforded to users through the California Consumer Privacy Act and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).13 They may need to reassess their business models and mechanisms as well, in order to deliver greater value and trust to an increasingly savvy and skeptical digital society.

Delivering value and assuring trust

When businesses require user data for their services, users increasingly recognize that they are giving up something of value—and expect commensurate value in return.14 And their willingness to share their data depends in part on how much they trust a service to defend their privacy. John Hagel, founder and co-chairman of Deloitte’s Center for the Edge notes that “gaining privileged access to data is likely to depend increasingly on the ability to build deeper and deeper trust with customers so that they are not only willing to share their data with the company, but eager to share more of it, because they believe they will receive more and more value in return.”15 When people see clear and meaningful benefits from their data, they are typically more willing to share it. This can enable more direct and authentic customer relationships, more personalized offerings and incentives, and greater retention and brand loyalty. Strong customer relationships can be particularly meaningful during economic downturns.

Services whose business models are based on advertising or data sharing can face additional challenges: How to protect and leverage data to provide greater value to nonpaying users, while using that data faithfully to deliver value to paying customers. Failure can invoke the ire of shareholders and regulators alike.

Global governments are increasingly regulating data-driven businesses, taking a stronger role in enforcing consumer protection, market competition, and sociopolitical stability. Some are focused on control through “data nationalization” policies; others are looking to protect consumers through a broader regulatory approach such as the GDPR. Business leaders, though, fear that governments will act hastily, worrying that politicians and regulators don’t fully understand what they’re trying to regulate.16 Consumers are often caught in the middle, increasingly dependent on such services yet unable to play a meaningful role in their evolution.

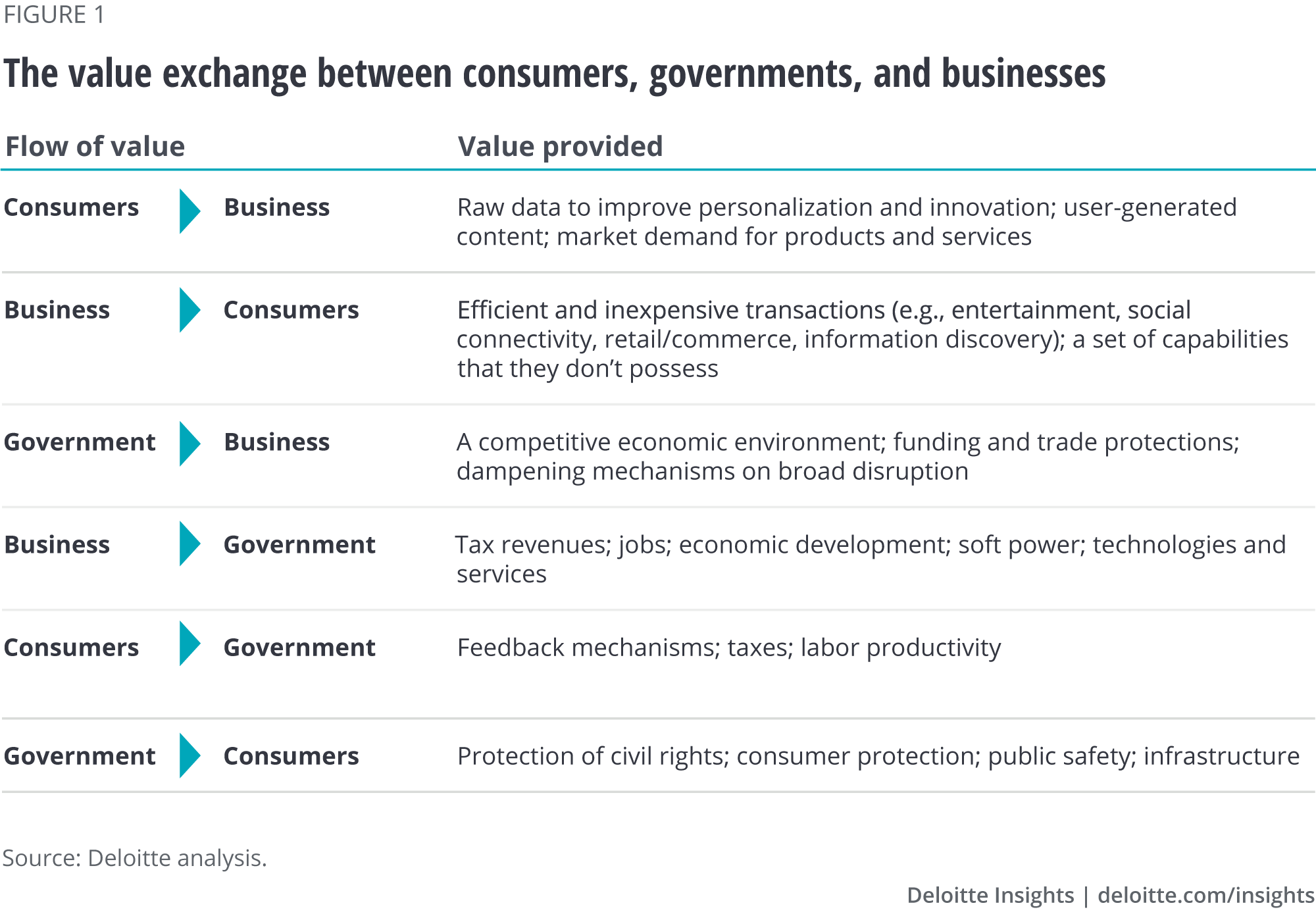

Value is clearly being exchanged between people, businesses, and governments, but it seems that the ecosystem has fallen out of balance.

This high-level view shows ways in which parties exchange value in the digital society (figure 1). Consumers increasingly perceive an imbalance.

- Seventy-two percent of adults say they personally see very little or no benefit from the data that companies collect about them.17 Seventy-eight percent of global consumers feel that businesses benefit more from the exchange of personal data.18

- In Deloitte’s 2019 Connectivity and Mobile Trends Survey, only 39% of respondents think companies are clear about how they use the data they collect.19

- Deloitte’s Global Millennial Survey 2019 found over 60% of millennials and Gen Z users feel that they would be physically healthier if they reduced their time on social media.20 Over half said social media does more harm than good.

- Sixty-one percent globally believe that elected officials do not understand emerging technologies enough to regulate them effectively.21 And yet 85% of consumers say the government must do more to regulate the ways in which companies collect and use consumer data.22

Although users remain hesitant to delete their accounts, their sentiments are empowering legislators and regulators homing in on fundamental issues of privacy and antitrust. How they act could affect every industry using data to innovate and deliver value.

Consumers see declining value from the collection of their data and limited transparency about that data post-collection, and they have developed a sense of unease about using these services and a willingness to confront social media companies’ perceived focus on their business models rather than privacy, data security, and behavioral manipulation.

Getting ahead of looming regulations

Digital technologies can scale quickly, and it is often only at very large scales that the unintended consequences become more visible. At this stage, public pressure often spurs regulators to install guardrails to keep the system from wobbling too much. According to the technological development theories of Carlota Perez, institutional change takes a lot longer to mature than technological and economic change. She also states that government institutions tend to address new issues with what has worked in the past. This sums up where our data-driven society is currently, as governments seek to “design appropriate new institutions and regulations at the turning point.”23

Governments around the world are pursuing various paths to regulation, some more heavy-handed than others. Businesses are caught between these maturing users and powerful regulators, worried that neither of these groups is fully qualified to rebalance the business of data.

Some of the solutions that US legislators are considering:

- Establishing a data protection authority

- Mandating that companies collect customer data via opt-in rather than offering an opt-out option

- Allowing the deletion of personal information upon request

- Making organizations provide a clear explanation of what personal and behavioral data will be collected, how it will be used, and with whom it might be shared

- Mandating reasonable security and data protection practices

- Permitting lawsuits and leveling tax penalties if violations occur

- Placing registration and additional protection requirements on data brokers

- Empowering the Federal Trade Commission to manage and enforce data collection and protection

Businesses might be well served to take each of these seriously and determine how they could better address them ahead of regulators. More already are, creating oversight boards and working more closely with regulators.24 Arguably, fixing a handful of core mechanisms could solve many of the problems afflicting social media and messaging services, and doing so could rebuild trust, unlock new business models, and set up services for a thriving, data-driven future.

The surface area of interaction

In our young digital society, top messaging platforms and social media services constitute a global surface area of interaction between people and data-driven business models. In the rush to scale free services to literally billions of users, the ecosystem of data collection, modeling, and targeting has grown enormously large and complex. This growth has enabled the advertising business model and its mechanisms to be exploited by third parties that enjoy anonymity at the expense of many others.25 For these reasons, regulators are pursuing tracking mechanisms, ad exchanges, and data aggregators to bring more transparency and accountability to the value exchange between users and data-driven platforms.26

For the largest digital platform companies, tracking mechanisms can extend the surface area of data collection.27 Most people are familiar with cookies, used on the web to identify us so that sites can deliver faster and more personalized experiences when we return to them. First-party cookies lower the friction of using sites and enable experiences to be more personalized.

But things get more complex: Web services can also add bits of data to other websites that can continue to capture interactions after users have traveled elsewhere. Third-party cookies, under growing scrutiny for tracking users without their consent, are being removed from top browsers, blocked by ad blockers, and controlled by regulators.28 Efforts are underway to replace third-party cookies with browser mechanisms that prioritize user privacy while still supporting the advertising ecosystem29—an example of how data-driven consumer-facing services and business models are already being rebalanced.

Beyond the web, many people spend their time in mobile apps that can engineer much finer views of how their users are interacting with content, other users, and the service itself. Trust, in these cases, may be predicated on a sense of containment—the security inherent to “walled gardens.” But such gardens are often a part of data ecosystems supporting their business needs, and it is in the tendrils of such ecosystems, often beyond the view of providers, where problems arise. When they do, the providers are usually held accountable.

The largest providers may have multiple audience aggregators—a web-based social media site, a mobile social media app, a messaging platform—and can capture user data across all of their properties. Some now include physical touchpoints as well, with the proliferation of facial recognition, smartphone point-of-sale, and dedicated voice assistants in the home. Providers can also buy data from other companies, securing access to things such as offline purchasing, home ownership, and education.

Ad and data exchange networks

Social media services’ targeted advertising platforms enable small businesses to reach audiences formerly beyond their sphere, and such services could gain importance in economic recovery. But their rapid growth has revealed critical shortcomings in their management.

After years of criticism and controversy, top social and messaging services are now largely transparent about their data collection and use. But that transparency vanishes in the opaque, ever-shifting landscape of data brokers and real-time ad bidding networks. When people visit a website, ad exchange networks broker access to the visitor, offering relevant profiles to the highest bidder. When ads follow us around the web, it is because the ad issuer is paying an ad exchange network to show that ad every time our pseudonymized cookie ID hits a new site with an advertising banner.

To make targeting more precise, ad exchanges enrich their user profiles by purchasing data from as many sources as they can. These sources can include numerous data brokers that are less than transparent in how they acquire data—and how accurately that data matches who we are. Some develop and offer profiles that may be wildly inaccurate,30 which doesn’t matter much for an online ad but could cause a mortgage application to be denied or health insurance to be withheld. And consumers can find it onerous to redress such errors or reach a data broker at all—if they can even identify the source of the faulty information.31 Shining light on these networks is an important focus area for regulators.

An additional risk in ad brokers and data exchanges is the amount of data that transits networks. There are no comprehensive security requirements that can help guarantee against leaks, data breaches, or unwelcomed access. For example, phone companies use location data from their subscribers to identify and fight fraud, but this data can trickle down into networks of location aggregators that are less regulated than telecoms.32 For legitimate businesses participating in ad networks, there may be limited visibility into who they end up partnering with across these exchanges. Increasingly, businesses are demanding greater transparency to vet and audit such partners so they can lower their risk.

Companies can lead the change

Opaque and unregulated data brokers and ad exchanges present a risk to people and business: They not only undermine the privacy and security of personal data—they can erode the value of that data through shoddy methodologies that introduce inaccuracies and liabilities. Lack of oversight has made them—and the companies that purchase their data—vulnerable to infiltration by fraudsters and dangerous actors aiming to destabilize populations and undermine democracy. If the largest social media and messaging companies were to use their might to radically overhaul these utilities, it could go a long way toward remediating their reputations, enabling greater value from data, and restoring user trust.

When data collection is transparent, secured, and contained within a single company, it can lower risk. Such businesses can channel user data back into their own innovation pipelines, wielding data-driven insights to deliver more value to users and customers. However, such “data hoarding” can provoke antitrust regulators increasingly aware of how much power can accrue to the largest data-driven businesses. Perhaps ironically, privacy legislation that would require companies to hold user data very tightly can reinforce monopolies. And yet competitive advantage may accrue to those best able to extract meaningful insights, rather than to those with the most data.

When data collection is transparent, secured, and contained within a single company, it can lower risk and potentially deliver more value to users and customers. But such “data hoarding” can provoke antitrust regulators.

There may be much greater untapped value in developing data liquidity between businesses, researchers, and governments. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, competitors have come together to share data and resources toward better solutions. Rivals are uniting to quickly develop robust “contact tracing” solutions to help mitigate the spread of the virus.33 Such efforts reinforce early data transfer policies that can enable users to move their data between services34 but they can also enable broader insights. For example, cities are tapping into 911 emergency calls to map the locations of likely coronavirus hot spots,35 and global health organizations have deployed dashboards that integrate and visualize real-time data from around the world.36 Breaking down information silos can enable faster responses to change: When data is shared across industries, then industry-scale insights, efficiencies, and optimization become available—critical capabilities at a time when change is disrupting entire industries. Additionally, businesses could potentially free themselves of data management and compliance burdens by supporting data trusts that centralize these responsibilities under regulated entities.37 Ad and data exchanges could become customers of such fiduciary data trusts.

This is admittedly a difficult path for businesses, consumers, and regulators. What’s missing is a broad, concerted effort to secure and validate data while placing privacy and social value at the center of business models. Technology, transparency, and smart oversight can safeguard data and guarantee privacy, but the current debate seems to treat those goals as mutually exclusive.

What does it all mean for the digital society?

Social media and messaging services have been some of the most widely adopted and rapidly scaling technologies in history. Digital-first and data-driven, they are models for data strategies across all industries. But few foresaw such broad and global use, and their business models, technical implementations, and architectures have had to shift, sometimes uncomfortably. Like many mature product offerings, many services are operating under the weight of earlier decisions while seeking ways to safely evolve. There may be no better time than now to take risks and make bold moves.

People, businesses, and governments may better address the challenges and opportunities of a data-driven society by looking at what is currently lacking in the debate.

For consumers:

- Take personal responsibility. Users should take more responsibility for understanding their part in trading data for free services. They should work to better understand when data is anonymous and when it is personal. And yet it is unfair to assume that an inscrutable end-user license agreement or hard-to-navigate preferences are all people need to protect themselves.

- Seek greater control over your data. If services give customers direct access to the data collected on them, people could take a greater role in the data economy. Consumer trust could grow if users could edit or remove data and migrate their data to other services. In the 2019 Deloitte Connectivity and Mobile Trends Survey, 91% of respondents agreed that they should be able to view and delete the data companies collect from the online services they use.38

For businesses:

- Use data to deliver greater value to customers and users. Deloitte’s John Hagel sums it up: “There’s an opportunity to expand the focus of our data gathering—paying much more attention to the data that will help us better understand the context of individual customers and the needs and aspirations that they have. Companies will need to focus on how they can use a much richer set of real-time data about customers to provide highly personalized products, services, and experiences in ways that evolve rapidly as customers’ needs and contexts evolve.”39

- Audit data supply chains. Data brokers and the targeted advertising ecosystem should undergo a comprehensive re-evaluation that prioritizes safety, security, and truth. Businesses could enforce greater transparency across the exchanges in which they participate, establishing strong compliance requirements and regularly auditing them for discrepancies. They may benefit from studying how supply chains have addressed these challenges.

- Focus on supporting public health and economic recovery. The COVID-19 crisis is a huge opportunity to put data to the test and to build goodwill by committing to a strong recovery, especially for those hardest hit. Businesses with valuable data resources should collaborate more with each other and with nonprofits, essential workers, and state and national governments.

- Explore data trusts. To overcome competitive hoarding while centralizing responsibility for privacy, security, validation, and compliance, third-party data trusts could be developed across industries. Such trusts could enable greater data liquidity and insights across industries while placing trust into regulated and fiduciary entities. Competitive advantage then becomes more about what companies can do with the data they can all access.

- Work together across sectors and industries. With so many companies in almost every industry hitching their futures to data, it may be imperative for them to better align and orchestrate beneficial outcomes for all. Doing so can establish best practices and values across industries while highlighting sector-specific nuances. Ultimately, such coordination may be critical to support better regulation, generate greater trust, and deliver real value to people, customers, and society.

For governments:

- Collaborate with businesses and consumers. Extending robust and well-considered regulatory constraints across data marketplaces could go a long way to containing the spread of data, limiting third-party access to data, and moving consumers into a more empowered and equitable role in how their data is used. By partnering with businesses, academia, and nonprofits, governments can generate greater goodwill and a shared mission to remediate the problems while aiming to extend greater benefits to all.

- Understand the nuances of the data economy. Governments can work to carefully evaluate how data is collected—whether that data is anonymous, pseudo-anonymous, or personally identifiable information—how the data is secured, and when and where it is shared. Work together to understand the implications of a data-driven society while avoiding unnecessary hysteria or hastiness.

A future reshaped by data

The idea that “data is the new oil” may be deeper than it seems. The largest data-driven companies are more valuable than the largest energy companies. Businesses can deliver greater performance and value from the “energy intensity” of strong data than they can from less informed approaches. The expanding data economy will likely shape the future as much as fossil fuels have built the past century.

The analogy is cautionary as well. Dirty oil doesn’t burn well and spews out polluting emissions. Its ability to fuel economies has driven the mounting costs of global warming and climate change. It has failed to solve for the conflicts and crises arising from competition for its control. And society’s over-reliance on it may be perilously fragile.

If the economy is becoming a data economy, and all industries are becoming data industries, then it will likely be critical—particularly at this fragile point—that business leaders, consumers, and governments come together now to develop a responsible set of principles, best practices, and solutions supporting a durable, thriving, and equitable digital society.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Telecom, media & entertainment collection

-

How cocreation is helping accelerate product and service innovation Article5 years ago

-

Talent and workforce effects in the age of AI Article5 years ago

-

2022 Digital media trends: Toward the metaverse Article3 years ago

-

Digital twins Article5 years ago