Ad-supported video: Will the United States follow Asia’s lead? TMT Predictions 2020

18 minute read

09 December 2019

In Asia—exemplified by China and India—ad-supported streaming video services reach over a billion people. Streaming services in the United States have focused on a subscription-only model. Will the success of the Asian model convince some US companies to follow their lead?

Amit Sharma (not his real name)1 admits that he watched way more of the recent Cricket World Cup2 than he planned to—including when he should have been working for his Hyderabad-based employer. “It was so tempting to binge-watch because I had an app on my smartphone that gave me access to every single game. I’m a big cricket fan, so I tuned in as often as I could.” He doesn’t regret it: “It was great to see so many matches, and lots of my friends and family were watching on their smartphones too. So, it was a social experience even though I was watching on my phone. It seemed like the whole country was.”

Learn more

View TMT Predictions 2020, download the report, or create a custom PDF

Download the infographics

Watch the video on this year’s TMT Predictions

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

It didn’t just seem that way. Over 100 million people in India watched the Cricket World Cup match between India and Pakistan on Hotstar,3 an advertising-supported video streaming service (which we’ll call “ad-supported video”). Hotstar has over 300 million monthly active users4 (MAUs), the key metric by which the user base of ad-supported video is measured.5 Nearly 50 percent of Indian smartphones have Hotstar’s mobile app installed on them. Thanks to ads, Hotstar provides much of its content for free, which has helped to quickly scale its viewers while generating revenue. To access premium content, such as live sports like the Cricket World Cup, Hotstar charges a subscription fee.

In China, India, and throughout the Asia-Pacific region (“Asia,” for short)6, ad-supported video is the dominant model of delivering streaming video to consumers. Sometimes it is combined with subscription services; in other cases, revenue comes from ads alone. It’s a big business that’s poised for serious growth.

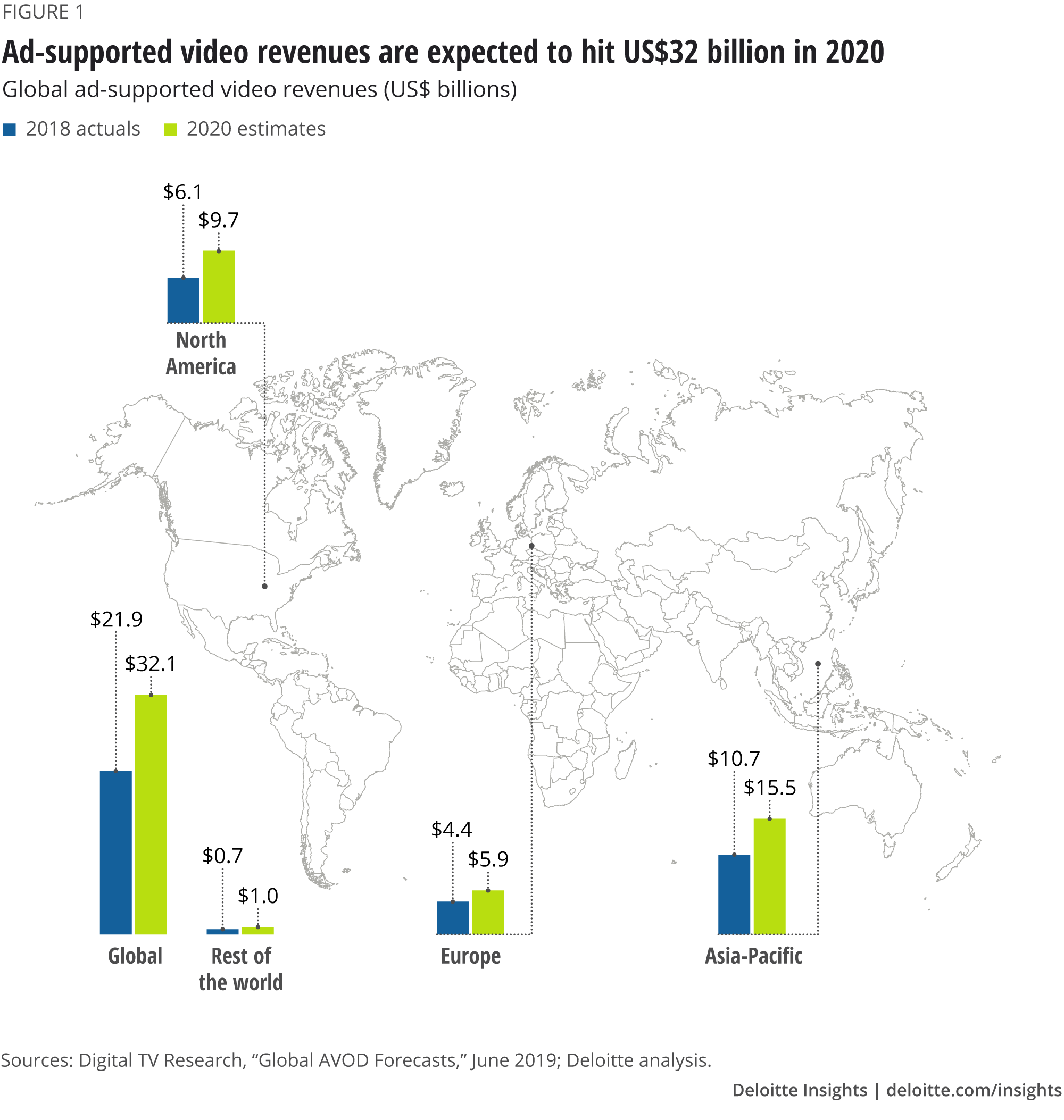

Deloitte Global predicts that revenue from ad-supported video services7 will reach an estimated US$32 billion in 2020. Asia (including China and India) will lead with US$15.5 billion in revenue in 2020, nearly half of the global total (see figure 1).

This prediction will document the rapid rise of ad-supported video services in Asia. Over a billion people in Asia watch ad-supported video services thanks to the advent of affordable 4G connectivity, low-cost smartphones, and business models that allows consumers to exchange their attention for free (or low cost) TV shows, movies, and sports.

Some Asian streaming services are using ad-supported video as the foundation for broader ambitions. After building huge user bases and reliable revenue from ad-supported streaming, they are developing formidable subscription businesses that feature original content, sports, music, and gaming. The goal is to become an entertainment platform that can satisfy both those willing to “spend” only their time and those who are willing to spend money, too.

In the United States, by contrast, most direct-to-consumer video offerings are pursuing the ad-free subscription model that companies like Netflix have used to dominate the American market. Consumers like avoiding ads: Forty-four percent of US consumers say an ad-free experience is a top reason they signed up for a streaming service.8 Yet evidence of “subscription fatigue” is emerging. Americans are growing frustrated that they need to manage and pay for so many subscriptions to watch what they want.9 As more TV networks, film studios, and tech companies launch their own subscription services, the fact that US consumers have an average of three such services10—and are already frustrated—suggests that only a handful can thrive. Where does that leave the rest of the 300-plus subscription-based services competing for attention and wallet share?

Could ad-supported video provide a model that brings consumers a greater variety of content in one place, at low (or no) cost? Could it offer a solution for advertisers looking for an alternative to the social networks and search engines that dominate the online ad market? Could it provide the basis for broad entertainment platforms that serve gamers, music buffs, sports fans, and everyone in between? If so, ad-supported video could be the latest successful Asian import to the United States.

Ad-supported video: The Asian model

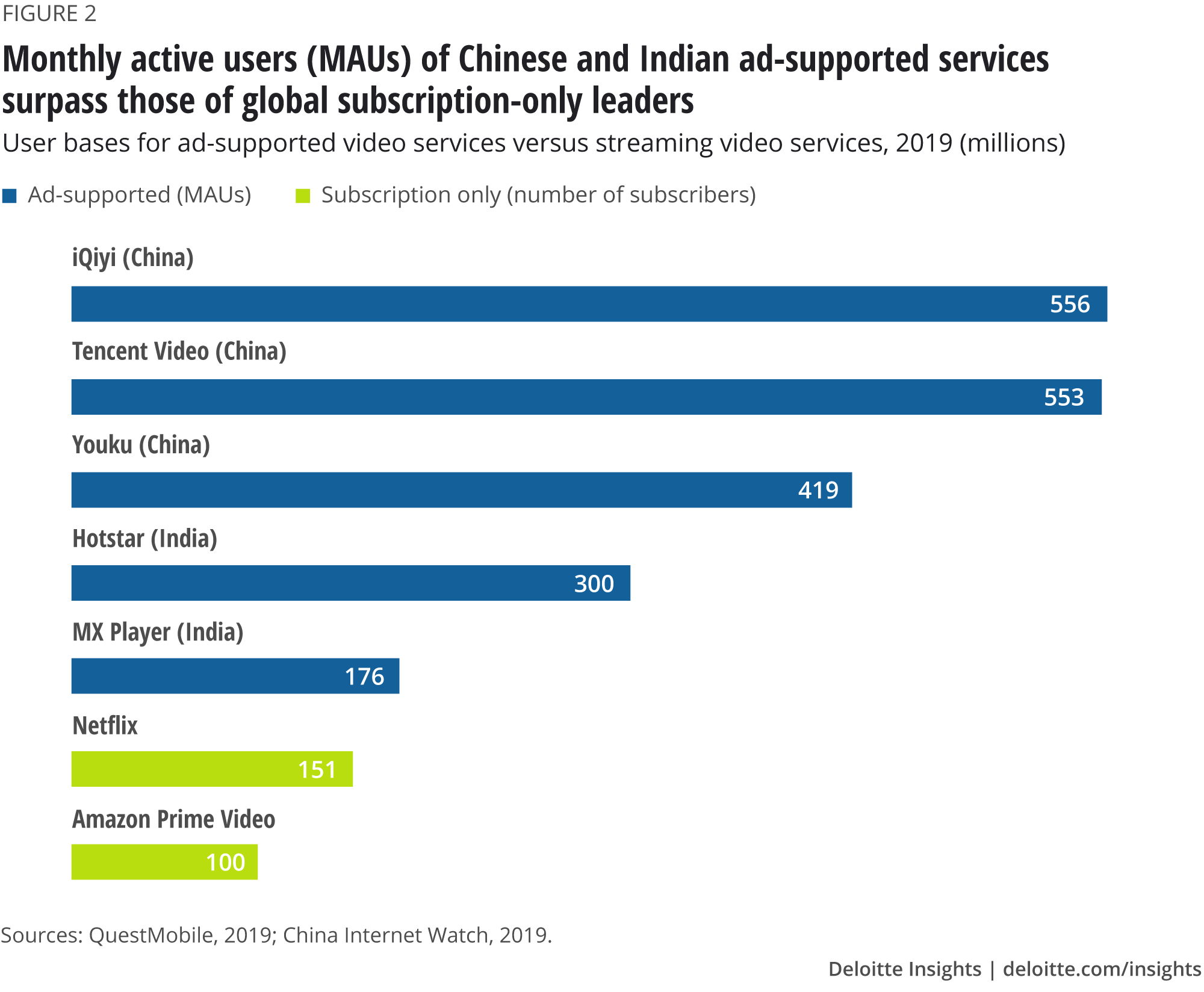

In Asia, the number of people who watch ad-supported video services is staggering: The user base of several leading services reaches nearly half a billion (see figure 2). Most of these services were launched after 2010. They have grown so big, so quickly, by making it easy for cost-conscious consumers to monetize their attention—essentially converting time spent watching ads into content they’d otherwise have to pay for. But that’s just the start. Many of the biggest ad-supported services are pursuing similar strategies to scale quickly and expand their sources of revenue.

What we might call the “Asian model” of ad-supported video has the following elements:

- Ad-supported core offering: In exchange for watching ads, users can view thousands of shows and movies. Much of this content is licensed from multiple studios and networks. Ads make it possible for anyone to watch, regardless of income.

- Subscriptions for premium content: Users pay a subscription fee to access premium content such as sports, foreign productions, and domestically produced original shows. Subscription revenue gives streaming services the funds to acquire broadcast rights to highly sought sports and top-tier international programming.

- Mobile-forward strategy: Asian streaming services have grown rapidly by focusing on smartphone users. In some countries, such as India and Indonesia, streaming services reach consumers who can’t access traditional pay TV. In others, such as China, pay TV is widely available, but streaming services deliver shows and movies to the device that consumers can’t seem to put down.11 In both cases, it’s easy for consumers to download an app and start watching.

- Multi-service bundles: By combining ad-supported video with streaming music and gaming, several services aim to make themselves a one-stop shop for digital entertainment. Telcos and media companies are using ad-supported streaming video to attract customers and diversify their revenue bases.

- Ad innovation: Services are experimenting with new formats and gamification to make ads, if not actually “fun,” at least more palatable to consumers.

We can see elements of the Asian model in action by taking a closer look at two of the world’s biggest ad-supported markets: China and India.

China: Ads underpin iQiyi’s ambitious expansion

Ad-supported streaming video services in China produced US$7.8 billion in revenue in 2018, about 35 percent of the global total.12 Mobile internet dominates in China. About 816 million Chinese consumers use a mobile device to go online, constituting 98 percent of all internet users—underlining the importance of the mobile-forward strategy.13 In 2019, smartphones surpassed TVs as the primary entertainment device, in part due to the popularity of ad-supported video services.14 China boasts three of the world’s five biggest ad-supported services, each of which is backed by one of the country’s three tech giants: Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent—collectively known as BATs (see figure 2). iQiyi (Baidu), Youku (Alibaba), and Tencent Video have roughly 500 million MAUs each.

iQiyi epitomizes several aspects of the Asian model. Launched in 2010 by China’s largest search engine, Baidu, iQiyi began as an ad-supported video aggregation service. In exchange for free content, users watch ad spots.15 By 2014, 212 million people were watching ads—and free video content—on iQiyi.

In the same year, iQiyi launched its own film division to produce original content and work with foreign producers as it moved to the second phase of its strategy: building a subscription business on top of its ad-supported service. In 2015–17, it produced dozens of original series and licensed high-quality foreign shows and movies, including content from Netflix.

In 2018, iQiyi launched an initial public offering as it pursued an ambitious expansion of its entertainment offerings. This included buying one of China’s top video game producers, Chengdu Skymoons.16 It has continued expanding its subscription offerings with exclusive live sports17 such as Spain’s top football league, La Liga, and by spending big on original dramas and movies.18

iQiyi is now the top streaming video service in the world, with over 560 million MAUs,19 100 million of whom are subscribers—up from 51 million at the end of 2017. The increase in members came at the cost of higher spending on content, which grew 65 percent between 2017 and 2018, to US$3.9 billion. As its membership base grew, the share of revenue from subscriptions increased from 38 percent in 2017 to 42 percent in 2018.20 While advertising as a percentage of total revenue declined in the same period, from 47 percent to 37 percent,21 ads have put iQiyi in a position to vie for leadership in China’s competitive entertainment market by helping it scale quickly, and by curbing losses as the company ramps up its investment in new forms of content.

However, even as it seeks to become a one-stop shop that can keep entertainment-hungry consumers on its platform, iQiyi is losing money.22 Although it grew revenue by 44 percent between 2017 and 2018, it lost US$1.3 billion, a 108 percent increase. iQiyi’s losses continue in 2019 as it ramps up its content investment.23

The scale of its investment is bold, but iQiyi may have little choice. It faces intense competition for consumers’ time and attention from other top streaming services; from short video service Douyin (branded as TikTok outside China), which has 480 million MAUs of its own;24 and from a robust pay-TV market.25 Moreover, iQiyi’s streaming competitors are making similar moves. Tencent Video, which is neck-and-neck with iQiyi in terms of MAUs and subscribers, recently spent US$524 million for a stake in New Classics Video, a Chinese film studio, and has partnered with the US National Basketball Association to stream games.26 Youku has spent big to secure exclusive online streaming rights to the FIFA World Cup, and to develop original hit series such as Day and Night, a crime drama that it serves up to paying subscribers.27 All three are also expanding abroad, or hatching plans to do so.

Ads have given iQiyi and other Chinese video services the scale to reach hundreds of millions of viewers —helping nudge the smartphone ahead of TV as the primary entertainment device in China and delivering billions in revenue. The free apps also allow consumers to “stack” services, watching what they like from each of the “big three,” without spending anything more than time and attention. For those who want access to sports and exclusive content, subscription options are available. Although their ambitions to create a “one-stop shop” for entertainment and to grow their subscriber bases are delaying their arrival “in the black,” Chinese video services would be in far worse financial shape without ad revenue.

India: Ad-supported video puts TV into the hands of millions—many for the first time

Pay TV in India is inexpensive, and in some states, nearly 90 percent of households have a television. But overall penetration rates remain below 70 percent.28 By focusing on mobile users, ad-supported video services have put “TV” into the hands of hundreds of millions and given some consumers their first access to video entertainment.

Indian consumers are cost-conscious, and many are willing to watch ads to access free or lower-cost video content.29 This has helped the country’s ad-supported video services to scale rapidly. So has the advent of affordable smartphones and 4G wireless with low data rates. Good phones with screen sizes exceeding six inches can be bought for around 7,000 Indian rupees, or under US$100. Affordability has put smartphones within reach of more consumers, and 400 million Indians—38 percent of the population—now own one. Of course, you can’t use a smartphone to watch videos without a reliable, affordable wireless connection. The entry of new telecom providers into the Indian market in 2016 reduced the price of data plans and made streaming affordable.30 India now has the highest data usage per smartphone in the world, at nearly 9.8 gigabytes per month.31

All this has proven fertile ground for streaming video services. In 2012, there were just nine streaming video services. In 2019, there are more than 35, with offerings from broadcasters, telcos, international and regional players, as well as independent content companies.32 Streaming video consumption is nearly ubiquitous among smartphone owners: Eighty percent of them use at least one streaming video app.33

Hotstar is the undisputed leader in terms of MAUs, with 300 million; and half of all Indian smartphones have the app on their devices. 34 It was launched in 2015 by Star, a media company that has 60 TV channels which produce content in eight languages; this reaches 90 percent of pay-TV homes in India.35 Star also happens to be wholly owned by Disney, giving the US-based media giant an up-close view of a rapidly evolving market burgeoning with competition and innovation.

With access to one-third of Indian consumers, including young sports fans, Hotstar is convincing advertisers to shift some of their TV ad budgets to streaming video.36 Advertisers are particularly drawn to the innovative ad models that Hotstar is experimenting with, such as gamification. This includes Watch’N Play, a trivia game with a social media flavor that tests viewers’ knowledge of cricket during match play. Advertisers can target their chosen demographic as part of the game using tools such as banner ads and video. Hotstar claims that Watch’N Play users spent three times more on Hotstar than average viewers and were more engaged with ads.37 Other streaming video services in Asia are developing innovative ad strategies as well. For example, when viewers of Indonesia’s OONA TV (185 million MAUs) watch ads and spend time on the platform, they earn rewards points called “tcoins” that they can redeem for discounts.38

Hotstar is the leader in India, but competitors from TV networks, telcos, and foreign streaming services (including Netflix and Singapore-based HOOQ) are fighting for consumers’ attention. MX Player is Hotstar’s top rival, with a fully ad-supported business model. Users can watch video content—including live news, original shows, and music—in 10 languages. Large Indian broadcasters are following Hotstar’s formula of ad-supported free video for “catch-up” content, with subscriptions required for live sports and premium shows. Meanwhile, telcos such as Airtel and Vodafone are aggregating content from multiple platforms and providing a payment interface. Over 200 million Indian consumers stream video from telcos, which could grow to 375 million by 2021.39

It may play in Bangalore and Beijing, but will it play in Boston?

In contrast to the Asian model, most US streaming video services take a subscription-only approach, in which users pay a monthly fee to access content ad-free. The two leaders, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, are subscription-based, with the latter included in Prime membership. Both Disney and Apple have launched subscription-only streaming services, albeit with low monthly fees intended to make the services “no-brainers” for customers.

The reality of subscription fatigue

The question remains: How many subscription TV services are consumers willing to maintain? Deloitte’s Digital media trends survey, 13th edition shows that consumers have an average of three streaming video services, a number that has remained steady for two years. How many spots are there “on the podium”? Certainly, consumers love having a choice of services, and avoiding ads is a top reason that consumers sign up for streaming video. Some viewers are especially ad-resistant, while others care less about avoiding ads than about maximizing their viewing options.40

But for most consumers, the costs of having multiple video subscriptions—in both hassle and money— are adding up.41 Consumers are especially frustrated when their favorite shows “disappear” without notice, and by the reality that they must subscribe to multiple services to watch their favorite shows and movies. These factors make streaming services seem progressively less valuable to consumers: For the same (or a higher) price, they get less of what they want. The problem will get worse as media companies withdraw rights from competitors and launch their own streaming services. Finally, there are the economic costs of multiple services. For consumers who cut the cord to spend less than they would with a pay-TV bundle, three services could be the maximum.42

The costs of launching subscription-only streaming services are mounting, too. The highest costs, as in China and India, are developing original content and obtaining rights to live sports. Netflix plans to spend US$15 billion on original content in 2019 and nearly US$18 billion in 2020, but in past years has usually ended up spending even more than it had originally planned. Apple spent a reported US$6 billion on original content for the launch of its Apple TV+ service.43 Sports rights, which Hotstar and the Chinese “big three” have brought to consumers, are also costly. Rights to broadcast National Football League games, the highest-rated sport in the United States and the key to attracting young male viewers, cost networks about US$6 billion per year, with big increases anticipated once the current contract ends in 2021.44 It is difficult to absorb these costs and make a profit from subscription fees alone.

US consumers—especially streamers—are willing to exchange attention for content

While few people love watching ads, Deloitte has found that US consumers are willing to exchange their attention for content,45 much like Asian consumers. That makes ad-supported services, with or without a subscription tier, an enticing option. This is especially true for media companies that cannot fund premium content without another source of revenue.

In Deloitte’s recent report, Are ads the prescription for subscription fatigue?, we analyzed responses from over 2,000 US consumers to understand their tolerance for ads. Consumers consider an average of eight minutes of advertising “fair,” while 16 minutes of commercials per hour is “too many” for them to watch any further. In short, after 16 minutes, they can’t take the pain and turn the program off. Interestingly, younger consumers (Generation Z, millennials, and Generation X) have a higher tolerance for ads than baby boomers and matures (consumers who are 72 and older).46 Young consumers feel an average of about 8.5 minutes is “fair” and 16.6 minutes is “too much,” compared with 6.6 and 15 minutes, respectively, for their older counterparts.

US consumers who watch live TV streaming services that feature ads, such as Sling TV, have a higher tolerance for ads across all generations. For example, Gen Z consumers who use a live TV streaming service believe 10.6 minutes per hour is fair and 18.7 minutes per hour is the point at which they stop watching.

Traditional TV, such as broadcast TV networks, shows up to 20 minutes of advertising per hour. That’s an “ad load” (i.e., the ratio of advertising minutes to total viewing minutes) of up to 33 percent, and clearly beyond what consumers consider tolerable, much less a fair exchange. But if the ad load is more reasonable, and the ads are more relevant to consumers, many are willing to watch them in exchange for content—especially if they get a discount. Seventy percent of consumers with three or more subscriptions said they would view advertising to get a new streaming service for a 25 percent reduction in price.47

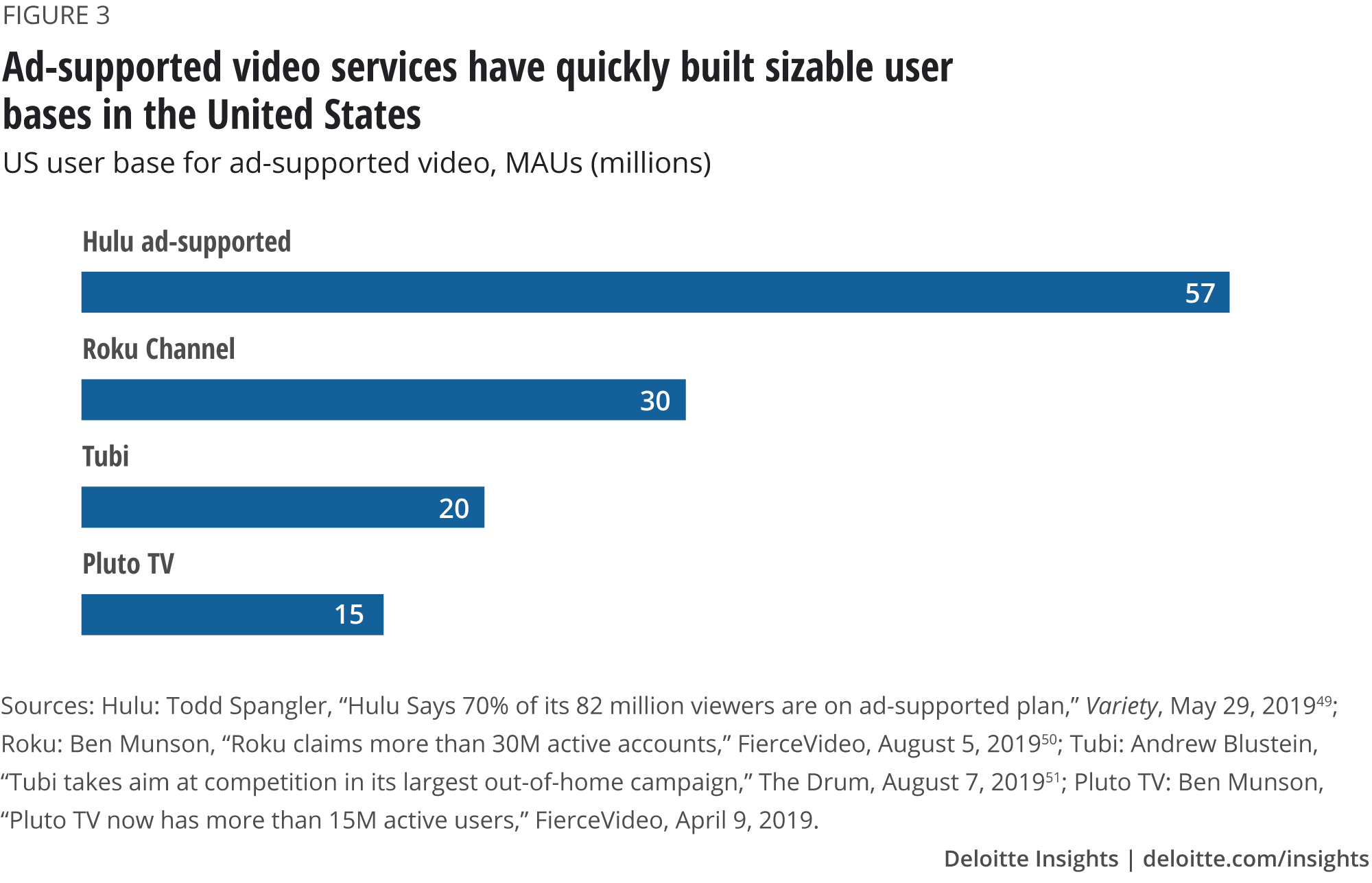

For evidence, look no further than the recent growth in the number of ad-supported video services. These include Hulu’s ad-supported service, which cuts the monthly fee from US$11.99 to US$5.99, an option that has attracted 57 million users, or 70 percent of Hulu’s customers (see figure 3). Ads generated US$1.5 billion for Hulu in 2018, a year-over-year increase of 45 percent.48 Roku was next on the list, with more than 30 million active users as of June 2019, up 39 percent from 2018. Pluto TV, with over 15 million monthly active users, was acquired in January 2019 by Viacom, and could be a pillar in the combined CBS-Viacom streaming strategy. Pluto TV is an aggregator that’s fully ad-driven. Amazon is also entering the fray, with its ad-supported IMDb TV.

While they lack the eye-popping numbers of Chinese and Indian services, the success of Hulu’s ad-supported tier, along with Roku, Tubi, and Pluto TV, evinces strong potential.

Ad-supported streaming services offer a fair exchange of attention for content—a big factor in their popularity. On traditional TV, a one-hour drama episode typically has 42 minutes of programming and 18 minutes of advertising: an ad load of 30 percent. On a streaming service, a TV drama episode averages five minutes of advertising and thus, an ad load of less than 10 percent.

Advertisers are rooting for ad-supported video services to take hold. The predominance of the subscription-only model has left advertisers out in the cold and made the ad market for pay TV remarkably resilient52 given its accelerating subscriber attrition, which included 1.5 million losses in Q2 2019 alone.53 Digital ad spending is increasing, but 60 percent of it goes to Facebook and Google (including YouTube) 54; only 3 percent of TV ad spending finds its way to streaming video services that offer professionally produced content.55 With the emergence of ad-supported video services with millions of monthly users, advertisers will have more options.

Not only options, but superior options thanks to dynamic advertising, which allows advertisers to serve consumers who are watching the same program with individualized ads based on their profile and data. Because most streaming services are IP-based, it is easier to deliver and execute more addressable and contextualized advertising. Additionally, using a platform that combines streaming video with data-driven advertising can enable an efficient market for exchanging personal data for content.

The bottom line

In Asia, ad-supported services will likely remain a pillar of video streaming. Ads provide much-needed revenue for services like the Chinese “big three” that seek to expand into new areas, such as gaming and music. Subscriptions will remain part of the mix for premium content, such as sports and original programs. However, ad-supported-only services will likely remain vital for consumers with little disposable income, and for whom “catch-up TV,” including sporting events that have already taken place, is enough.

In the United States, ad-supported video services could grow rapidly. With over 300 streaming services available today and a raft of high-profile services entering the market, there simply isn’t room for them all. Consumers will likely select a handful of “must-have” subscriptions—whether that’s more than three remains to be seen. Big media companies with large libraries that don’t “make the podium” could launch their own ad-supported services, with or without a subscription tier. For other services, providers may have to decide between making them subscription-only or joining an ad-supported aggregator. Then there’s the matter of paying for the original programs and live sports that attract subscribers; ad revenue can surely help fund content development and acquisition, as it has in Asia.

Some US-based streaming giants that use a subscription-only model may opt for an ad-driven model in value-conscious markets.

In both Asia and the United States, advertisers will likely move more of their spending to ad-supported services, attracted by millions of “eyeballs,” the ability to target individual consumers, and the certainty that their brands will be attached to professionally produced shows and movies—known quantities in comparison with user-generated content.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

Robots on the move: Professional service robots set for double-digit growth Article5 years ago

-

Private 5G networks: Enterprise untethered Article5 years ago

-

High speed from low orbit: A broadband revolution or a bunch of space junk? Article5 years ago

-

Bringing AI to the device: Edge AI chips come into their own Article5 years ago