My antennae are tingling: Terrestrial TV’s surprising staying power TMT Predictions 2020

18 minute read

10 December 2019

Think antenna TV is dead? Think again.

Learn more

View TMT Predictions 2020, download the report, or create a custom PDF

Download the infographics

Watch the video on this year’s TMT Predictions

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

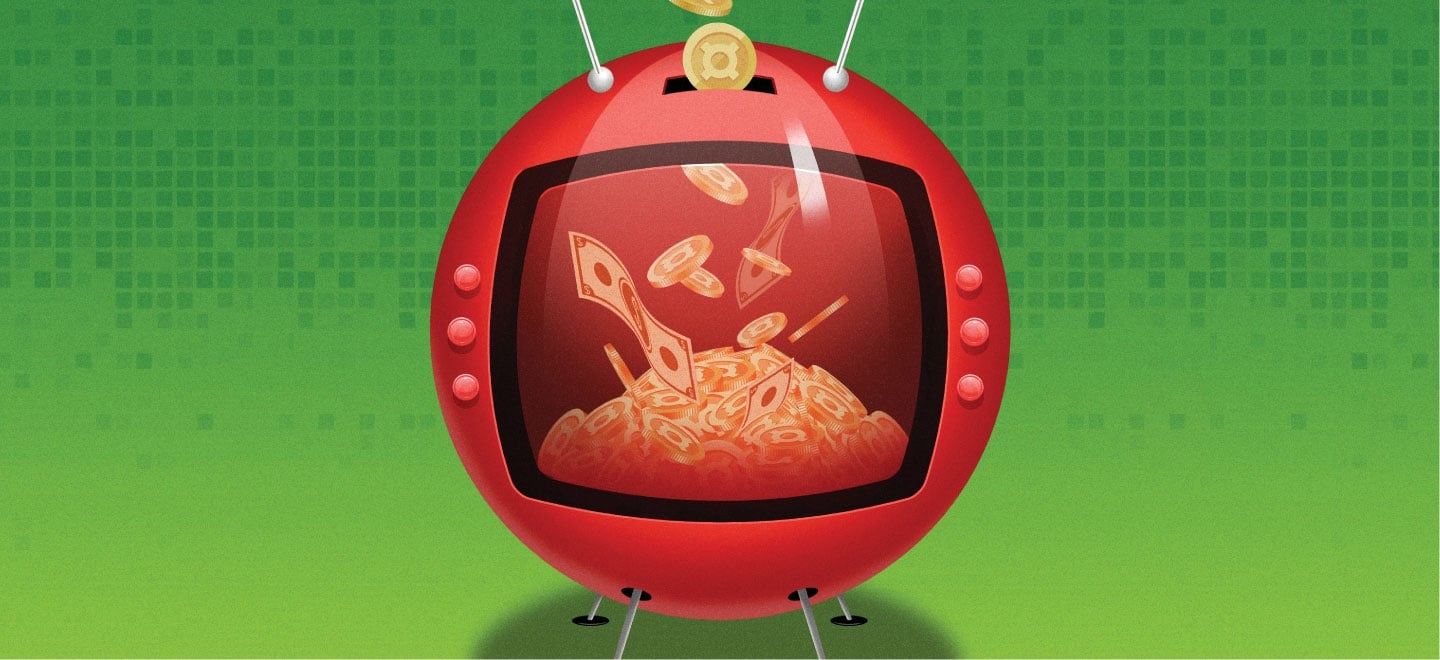

In the 1970s, TV antennas dominated skylines worldwide. In 2020, they may be about to do so again.

Surprised? Hold onto your hats: We predict that in 2020, at least 1.6 billion people worldwide, representing 450 million households, will get at least some of their TV from an antenna. And that’s the low end of the estimate: Extrapolations from verified data suggest that number may even be as high as 2 billion. Along with a predicted $32 billion in 2020 revenues from ad-supported video on demand (AVOD),1 antenna TV is helping the global TV industry keep on growing even in the face of falling TV viewing minutes and, in some markets, increasing numbers of consumers cutting the pay-TV cord.

Who’s paying for all that free TV? Advertisers. We predict that global TV-ad revenues will grow by more than US$4 billion in 2020, reaching US$185 billion in 2021 compared to US$181 billion in 2019. In terms of magnitude, this market size change is not wildly out of line with general consensus, but the direction we expect it to take is different. While some are anticipating TV ad revenues to fall by US$4 billion between 2018 and 2021,2 we think it will grow by about the same amount. That’s not a big dollar difference, but up is better than down!

Why do TV antennas matter? A Mexican broadcaster in 2019 may have put it best: “Broadcast on-the-air television is the most efficient media to tap the mass market.”3 The sheer number of antenna TV viewers in an age of proliferating entertainment alternatives raises some interesting questions. First, just how big is the antenna TV market? Second, what headwinds does the overall TV industry face? And third, how and why is the TV ad market not only so resilient, but growing?

Deconstructing the TV industry: Broadcasters, distributors, and who pays whom

Understanding exactly who does what and who pays whom in the TV industry can be confusing, especially in an age where delivery technologies and mergers and acquisitions are blurring the lines. Here’s a short primer.

The TV industry consists of two basic types of company: broadcasters and distributors. In the simplest terms, broadcasters are the companies that create and aggregate TV content. Example of relatively pure-play broadcasters—companies that make almost all their revenues from advertising or licensing fees, and do not have a significant distribution business—include CBS in the United States, BBC in the United Kingdom, RAI in Italy, NHK in Japan, TVRI in Indonesia, Globo in Brazil, and SABC in South Africa. They produce their own shows (dramas, comedies, news, sports, and so on) as well as buy shows from studios, and then package them up into channels, each of which includes its own lineup of shows presented in a specific order at specific times as part of their linear schedule.

When TV was in its infancy, the only way to get those shows in front of viewers was to transmit them over the air, and broadcasters spent billions on TV towers to send their programs to antenna-equipped viewers. As we discuss in this chapter, this legacy has continued, with many broadcasters offering free (to the viewer) on-air television to this day.

However, with advances in technology and infrastructure came alternatives to over-the-air transmission, and that’s where distributors come in. They go by different names in different countries; in the United States, they are properly called MVPDs (multichannel video programming distributors), although the average American generically calls their services “cable,” even when the distributor is not an actual cable company. Examples of relatively pure-play TV distributors—companies that make almost all their revenues from distributing other companies’ content and providing internet access, and that do not have a significant broadcast business themselves—include Charter in the United States, Dish Mexico in Mexico, Vodafone Kabel Deutschland in Germany, Asianet in India, KT Skylife in South Korea, and OpenView in South Africa.

Distributors, whether pure-play or not, are the companies that today transmit all of the world’s TV content to viewers—except for the on-air programming broadcasters still make available through antenna TV. Typically, a distributor takes channels from multiple broadcasters and organizes them into sets (called “packages” or “bundles”). It then physically sends these bundles to the viewer using whatever technology it currently has in place: coaxial cable, fiber-optic cable, telephone lines, satellite dishes, or even the internet.

Broadcasters make most of their money from advertisers, who pay to place commercials on the broadcaster’s shows. Broadcasters also make some money from distributors, who pay broadcasters retransmission consent fees for including their channel(s) in the bundle. However, most broadcasters don’t receive any money directly from viewers. Distributors, on the other hand, make almost all of their money from subscribers, selling bundles of channels to viewers for around US$110 a month. They do not, on the whole, sell commercial slots to advertisers.

The distinction between broadcaster and distributor has been steadily eroding at the corporate level, as companies that started out as distributors bought up broadcasters and vice versa. In fact, the majority of the TV industry players in the world today are not pure plays: They are both broadcasters and distributors.

The terminology around these players can also be confusing. In this chapter, we use “pay TV” to refer to all TV content that viewers pay a subscription fee to receive—whether the delivery mechanism is cable, fiber-optic, direct broadcast satellite, or the internet (a mechanism known as a virtual MVPD, or vMVPD), and whether or not the same corporate entity owns both the broadcaster and the distributor. In some circles, however, this market is known as the cable-plus or MVPD market.

This chapter also uses the term “traditional TV” to refer to antenna TV, cable TV, telco-provided IPTV, satellite TV, and vMVPD combined. Traditional TV includes all free-to-air and pay linear TV provided by broadcasters, whether via an MVPD or through an antenna. It does not, however, include services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, which are classified as subscription video on demand (SVOD) services, or user-generated content (UGC) services such as YouTube. Both SVOD and UGC are TV-like in various ways, and viewers often substitute them for traditional TV, but there are important differences, and they are not considered part of the traditional TV industry.

The numbers: Sizing the antenna TV market

To the best of our knowledge, no one has ever published global data on antenna TV market size. Some data for individual countries exists, and regulators have written about the various shifts from analog terrestrial TV broadcasts to digital (an important topic for reallocating spectrum),4 but there does not appear to be any global study examining how many people view at least some TV using an antenna.

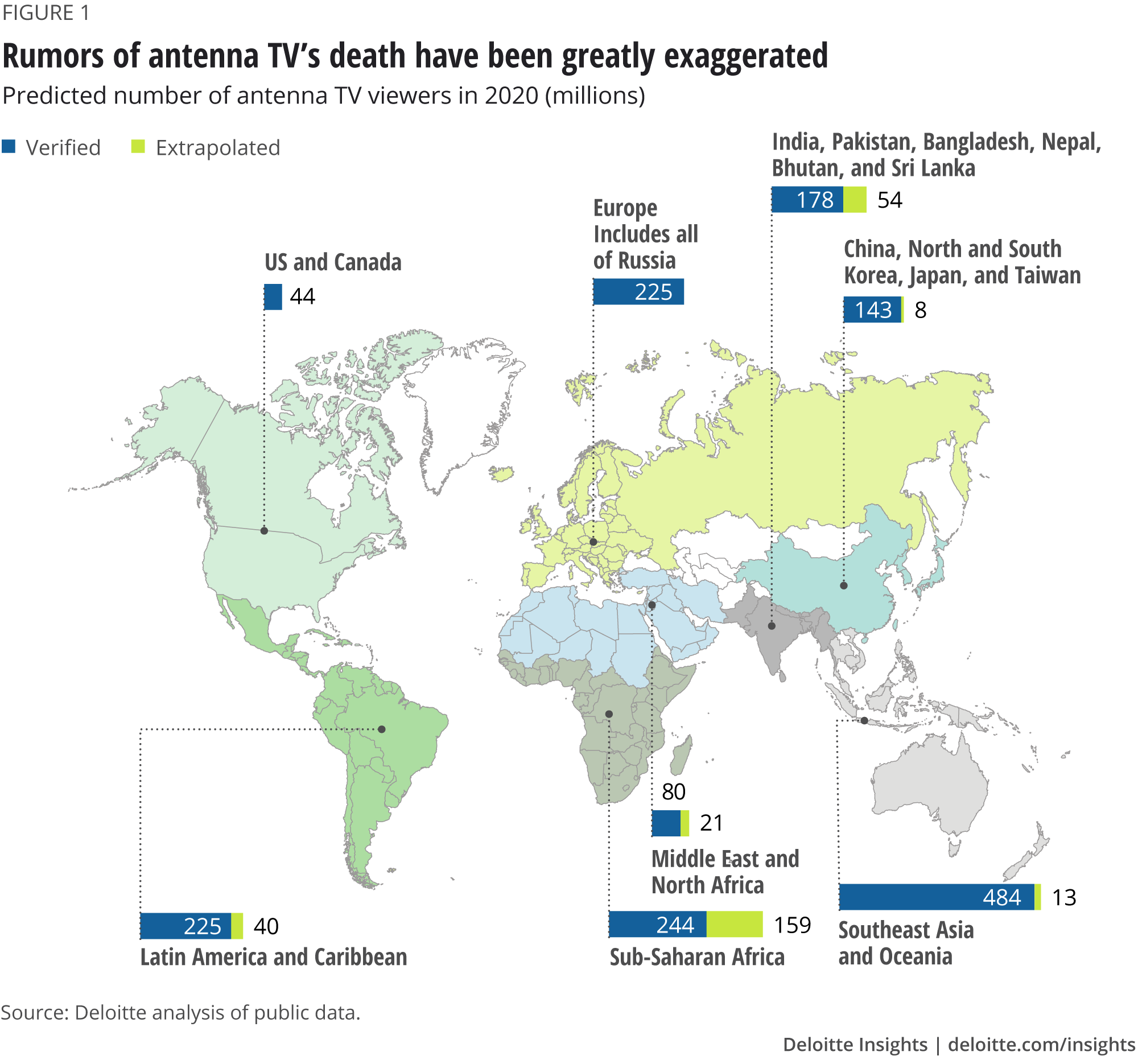

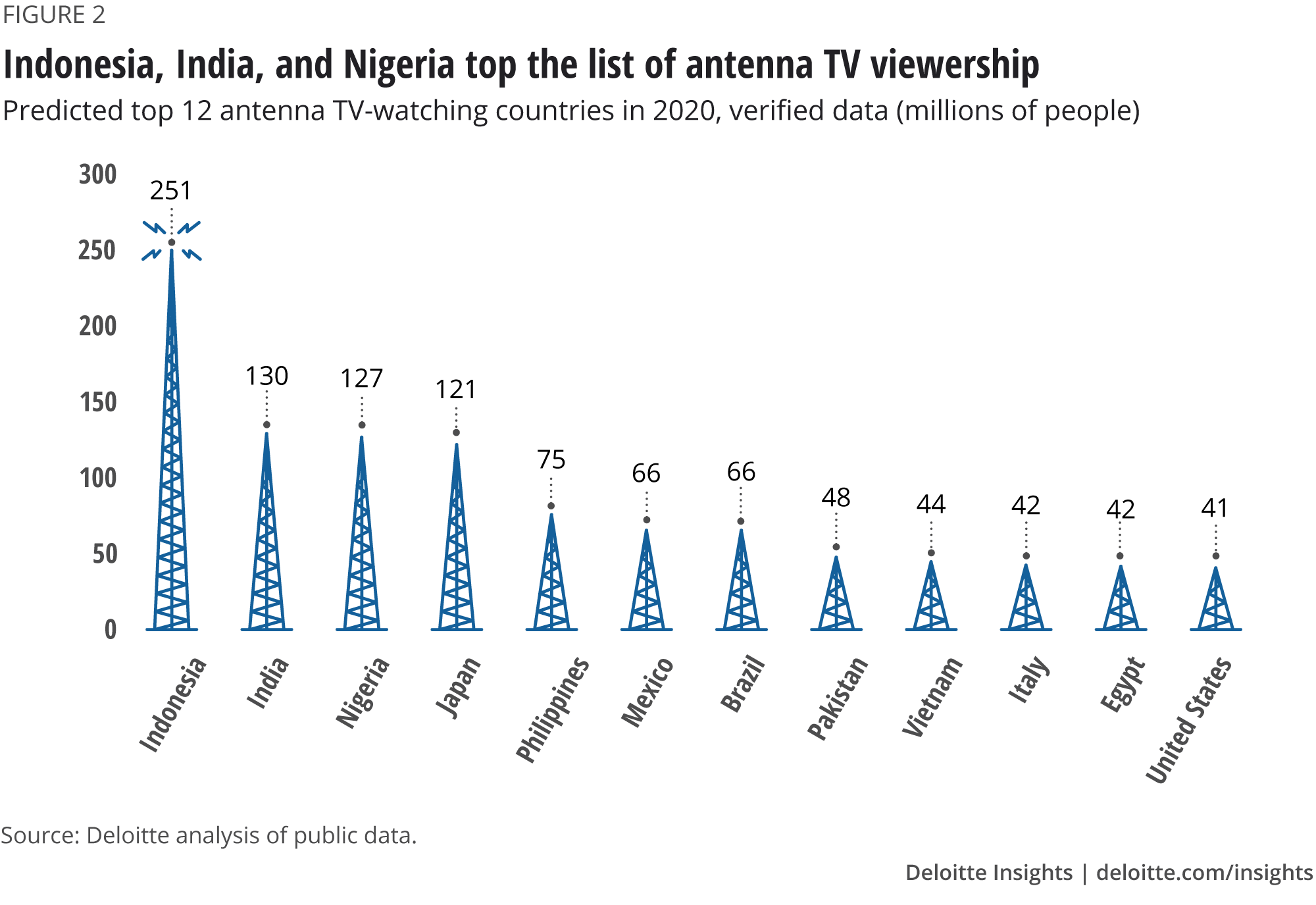

Our estimate of 1.6 billion antenna TV viewers in 2020 is based on verified data from 83 countries with a combined population of 6.6 billion people (figure 1). Of these, Indonesia, India, and Nigeria are expected to have the most antenna TV viewers (figure 2). If we assume that countries that lacked verified data resemble their neighbors in terms of antenna TV penetration, the estimate of global antenna TV viewership in 2020 rises to a whopping 2 billion. For context, this extrapolated number is roughly 50 percent more than all of the people paying to watch TV over cable, telco-provided internet protocol TV (IPTV), and direct broadcast satellite in 2020 … combined.

Not your grandfather’s rabbit ears. But sometimes they are

Fifty years ago, TV antennas tended to come in two kinds: the classic pair of rabbit ears that sat on top of the TV (for people lucky enough to live in an area where indoor coverage was good enough), or roof-mounted UHF/VHF aerials, which were large—often 10 meters tall and weighing more than 100 kilograms—and usually had to be professionally installed. Both kinds worked by receiving analog signals from towers broadcasting tens of thousands of watts.

Depending on the market, both kinds of analog antenna are sometimes still seen today. However, digital antennas have now also joined the mix. Some are roof-mounted, though these are usually smaller and lighter than their analog counterparts, and are often self-installed. Indoor digital antennas also exist, sometimes mounted on or near the TV, other times located near a window with a cable to the TV. These indoor versions, which look something like a 10-inch tablet, can cost as little as US$25 while pulling in stations from 50 miles (80 kilometers) away.

These self-installed digital antennas can receive between 10 to 30 channels, at no cost to the user. What’s more, the signals come through in uncompressed full HDTV, unlike many cable, satellite, and telco TV offerings that compress signals with some loss in visual quality. On the flip side, in markets with advertising, free-to-air broadcasts carry the full load of TV commercial advertising. In the United States, this averages 15 minutes per hour, or a 25 percent ad load.

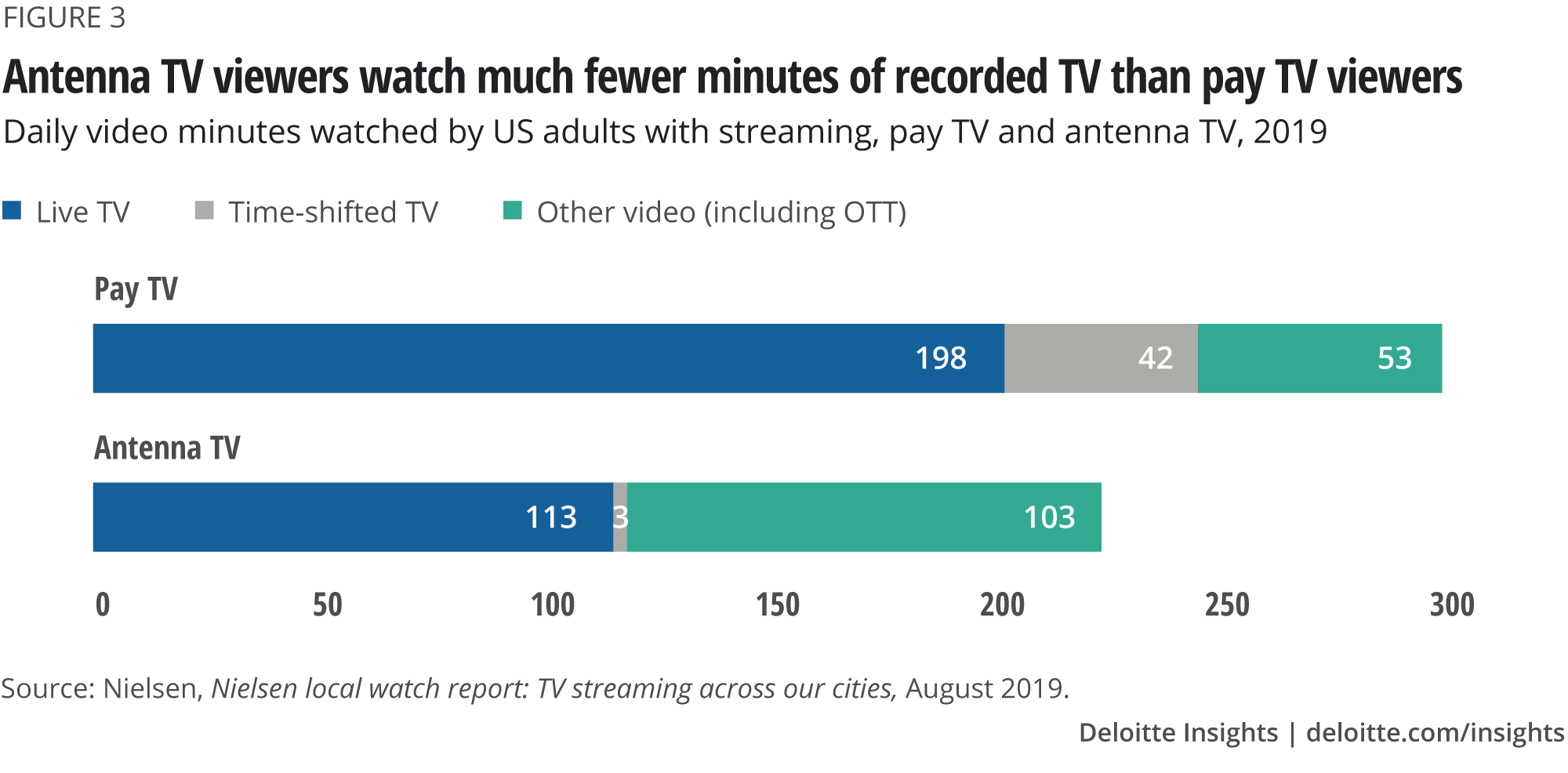

Digital video recorder/personal video recorder (DVR/PVR) solutions exist that can be easily connected to a digital antenna. Costing about US$200, they are basically the same as the boxes that pay TV companies use. However, it is unclear how many antenna users worldwide also have a DVR/PVR box. Based on data from May 2019, US adult antenna TV viewers who also have streaming TV options watched only three minutes per day of time-shifted TV, while those who had pay TV watched 42 minutes per day (14 times more, figure 3).5 This suggests that either very few antenna TV viewers own a recording device, or they don’t use them very much. Assuming this trend applies to other countries, the implication is that time-shifted TV viewing—and, therefore, the ability to skip ads—among antenna viewers is dramatically lower than among pay TV viewers.

The headwinds: The traditional TV industry can use antenna TV’s help

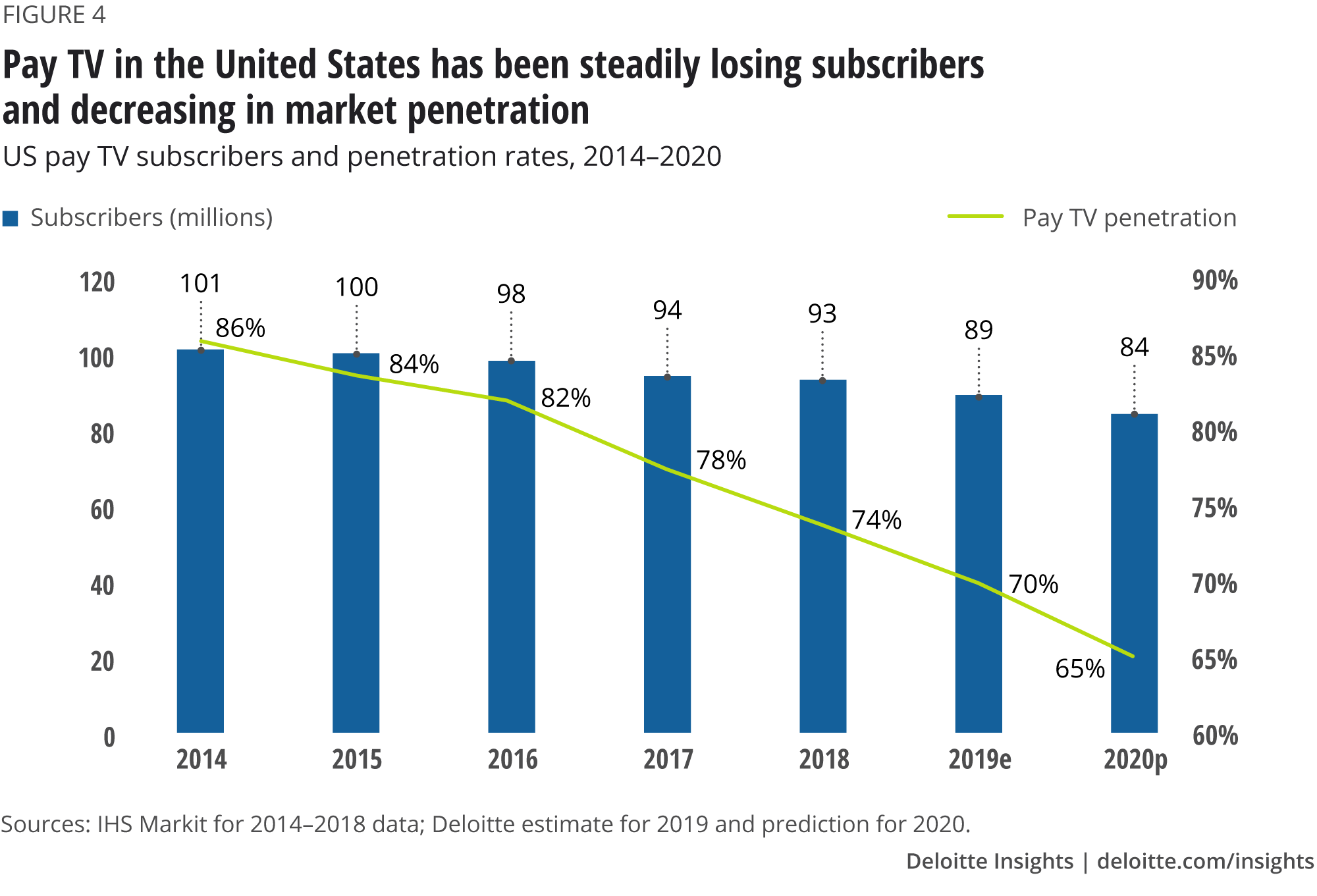

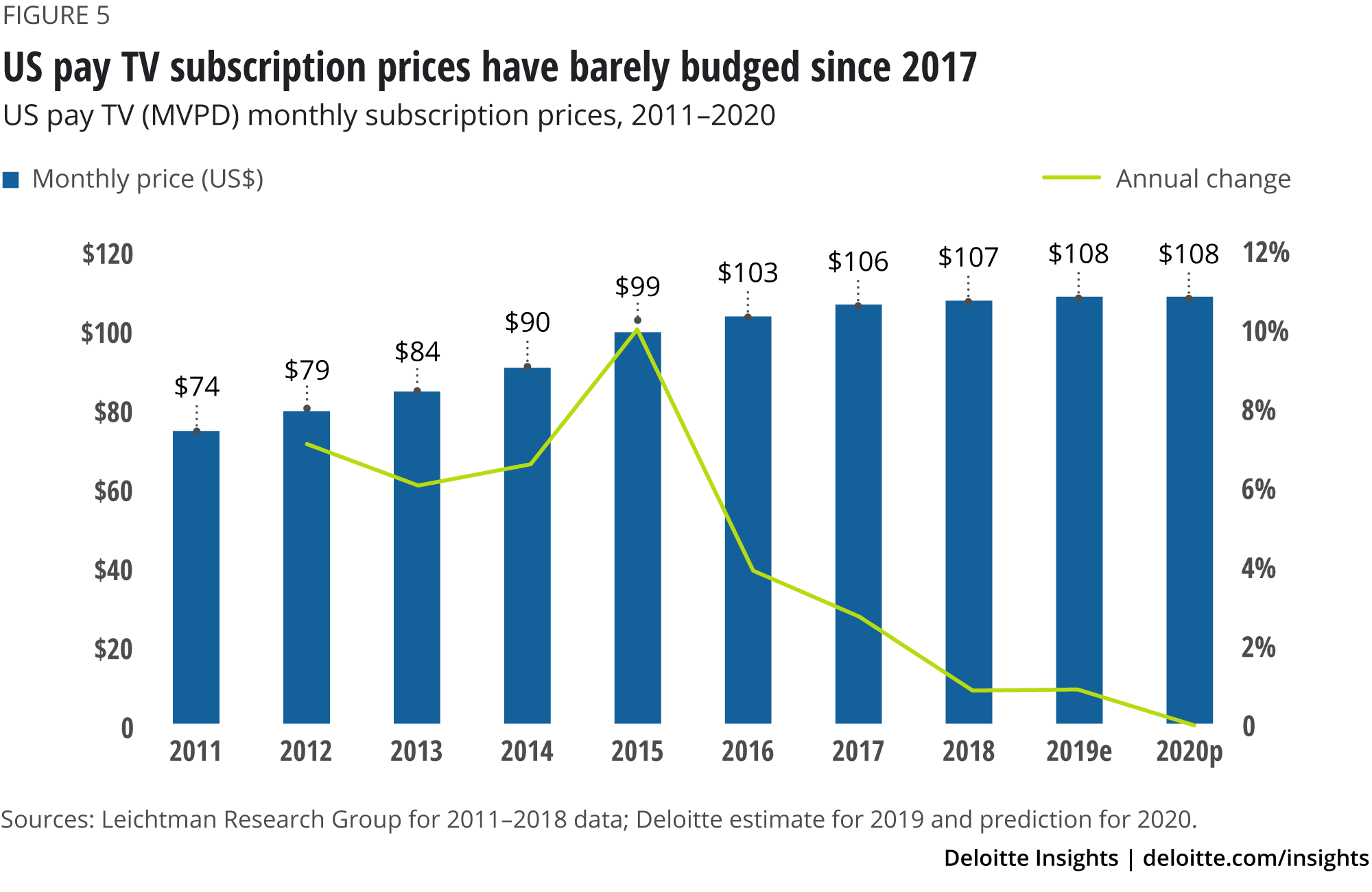

Antenna TV’s resilience is a bright spot in the overall TV landscape, as the traditional TV industry as a whole (pay TV and antenna TV combined) is facing headwinds. Several signs in the important US market point to challenging times ahead. In the United States, we predict that the number of pay TV subscribers will decline by 5 million in 2020, in line with recent trends (figure 4).6 Further, we anticipate an average zero percent price increase for what Americans pay for pay TV in 2020—slightly worse than in 2018 and 2019, and much lower than between 2012 to 2016 (figure 5). Finally, we expect TV viewing minutes in 2020 to decrease by 5 percent overall, with double-digit declines among the youngest age groups. We base this prediction on the year-over-year decrease among all demographics in 2019 (figure 6); The decline in 2020 will likely be less steep, due to the Summer Olympics and the US presidential election, but it will almost certainly be a decline.

Similar trends are afoot in other countries as well. Brazil, Mexico, Hong Kong, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Israel, Venezuela, and Ireland all are seeing ongoing declines in pay TV subscribers.7

TV viewership growth in the rest of the world more than offsets these declines … for now. On a global scale, three-quarters of the world’s pay TV operators will likely gain subscriptions between 2018 and 2024, and two-thirds will see their revenues increase over that same period.8 In aggregate, the number of pay TV subscriptions worldwide is expected to rise by 8 percent between 2018 and 2024, reaching 1.1 billion in 2024.9 But even though more people are subscribing to pay TV, the industry as a whole still isn’t making as much money as it used to: Global TV industry revenues are forecast to decline by 11 percent in 2023 compared to 2019 levels.10

The ads: Why are TV ad revenues still growing?

Advertisers are still showing faith in traditional TV. In the United States, average annual upfronts (the annual presales of ads for the whole year held every May, which generate about half of annual big-brand TV advertising spend) went up by 2.4 percent in 2019 year-over-year, and they are expected to rise by another 1.8 percent in 2020.11 And that’s just the average: Some networks even reported double-digit growth.12

Why aren’t things worse for broadcasters’ TV ad revenues, at least in markets such as the United States where viewership is falling? Here, antenna TV may well be one of the factors making the difference.

Antenna TV viewership is growing or at least stable in several large ad markets, representing tens of millions of antenna TV watchers who (mostly) are not skipping ads while watching traditional TV. Antenna TV is big in the United States’ massive ad market, for instance, and it is getting bigger. More than 40 million Americans in at least 16 million homes watch antenna TV,13 up 48 percent since 2010; 10 million US homes have only antenna TV.14 In the United Kingdom, nearly 30 million people in 12 million homes watch antenna TV, up 2.3 percent since 2012, and 11 million of those homes have only free antenna TV as their source for traditional TV, although many of those also subscribe to SVOD services.15

Besides antenna TV’s growth, another reason for TV advertising’s resilience is the development of targeted or “addressable” ads. If a home has the right kind of box or TV—more than half of US homes in 2018,16 and about 40 percent of UK homes in 201917—advertisers can deliver specific ads to specific households (though not to individual viewers) at premium rates (three times that of a traditional ad, in one US instance).18 In the UK, broadcasters are working together to get more addressable ads in front of more viewers as Channel Four uses Sky’s AdSmart technology.19 Addressable ads are likely to generate revenues of nearly US$3.4 billion in 2020 in the United States, up about one-third over the previous year, and 4.5 times more than in 2016.20 Although still only a small part of the United States’ overall US$70 billion annual spend on TV ads, these ads are helping the TV industry to offer advertisers features such as personalization and viewership measurement that previously were possible only with digital ads, as well as drive much higher prices per thousand views.

The final factor contributing to TV ad spending is that the ongoing shift to digital ads of all types isn’t a one-way street. Although digital has been growing, and is expected to continue growing, individual ad buyers are constantly reallocating their spending between digital and TV (as well as other categories); but TV and digital combined are expected to represent just under 80 percent of global ad spending by 2021.21 According to a recent UBS study, half of the surveyed ad buyers are planning on shifting advertising dollars from TV to digital … but the other half are shifting dollars from digital back to TV.22 Prominent names that have publicly announced reallocating at least some money to TV include JPMorgan,23 P&G,24 and Amazon.25

Research supports the business reasons behind that shift. One UK study found that TV ads have the highest ROI of any channel.26 A US study found that TV ads were best at building an emotional connection with a brand, and that the most effective campaigns were TV-led.27 At a high level, findings like these suggest that the choice is not binary between TV and digital; rather, advertisers should find a mix of the two that work together. Given that some companies in recent years have gone “all in” on digital,28 it is not surprising that some dollars—billions of them, in fact—may be coming back to TV worldwide. (To be clear, in some regions, the shift to digital is at an earlier stage than in the United States or the United Kingdom, so digital is still gaining share in the ad market globally.)

The bottom line

TV may not be growing at the rate it did 20 years ago, but neither is it collapsing, and both advertisers and broadcasters need to think of it in those terms.

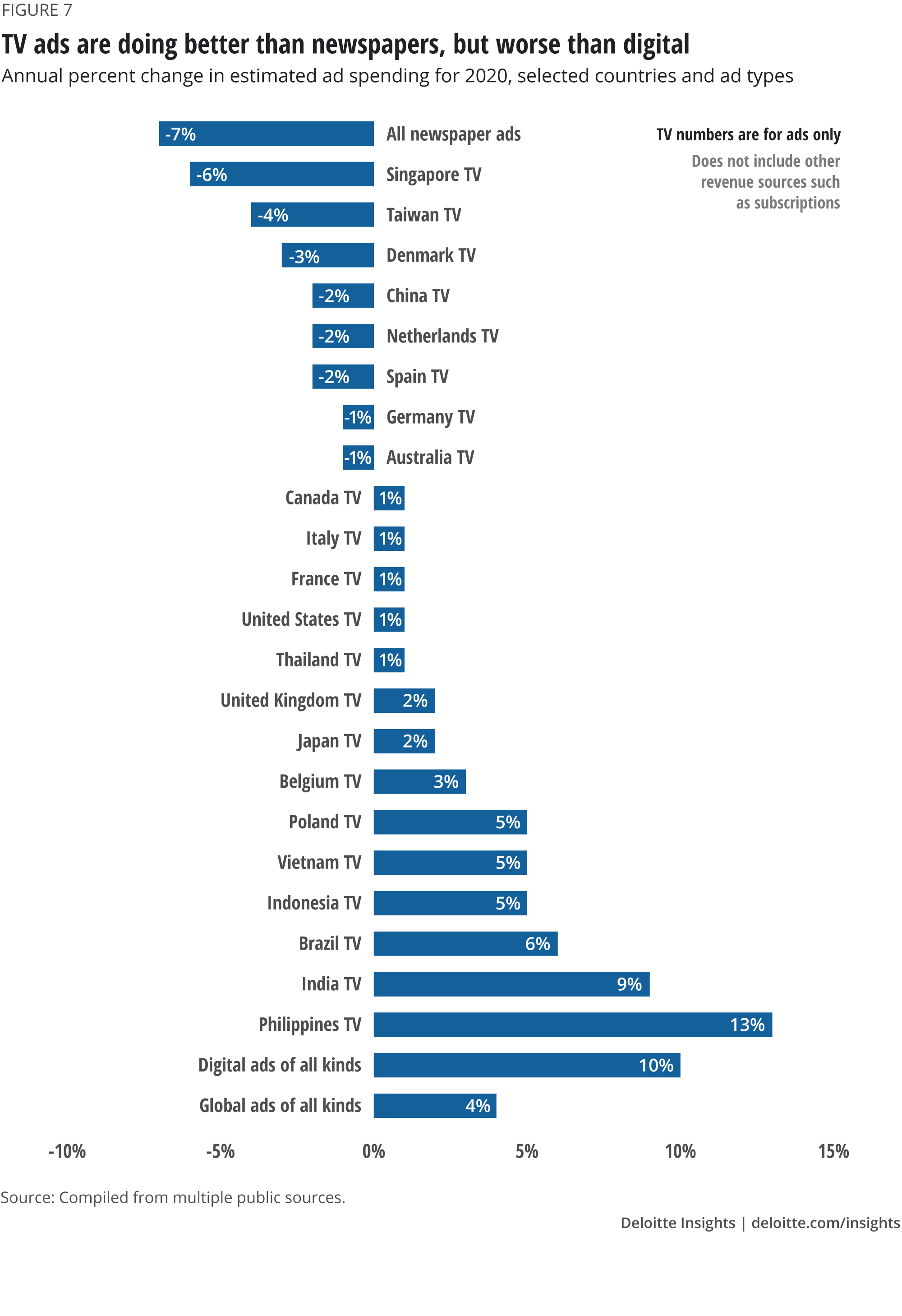

TV ads, first of all, are not following the same path as some other traditional media ads. TV ad revenue is not dealing with multiyear double-digit declines. Although our discussion has mainly focused on the large US market, TV ad spending in 2020 is also expected to grow in dollar terms (although usually losing share of the total ad market) in the Philippines,29 India,30 Brazil,31 Vietnam,32 Indonesia,33 Poland,34 Belgium,35 Japan, 36 the United Kingdom,37 Thailand,38 Canada,39 France,40 and Italy.41 And although it is expected to shrink even in absolute dollar terms in some markets (Australia,42 Germany,43 Spain,44 Netherlands,45 China,46 Denmark,47 Taiwan48 and Singapore49), the annual declines are moderate rather than severe, and they are still less than the declines in ad revenues for other kinds of traditional media, such as newspapers (figure 7). Interestingly, many of the higher-growth TV ad markets are also ones where antenna TV usage rates are the highest.

It’s worth noting, however, that the future of TV advertising is by no means certain. While we can be fairly confident about its growth in 2020—Olympics plus the US presidential election make for predictable growth—the picture becomes cloudier as we peer further into the future. We believe that total TV ad spend in 2021 should still be higher than in 2019, even if slightly lower than or flat with 2020 levels. For 2022 and later, the crystal ball becomes even murkier. Although it seems probable that the current trend will continue—basically flat TV ad revenues, with uplifts once every four years—at least one study predicts a “TV tipping point” in 2022 and beyond.50 It argues that TV’s decreasing reach combined with the ongoing drop in TV viewing minutes—especially among desirable younger demographics—is reducing TV’s current ROI advantage over other forms of advertising. And as that ROI advantage erodes, the study predicts, TV ad revenue will begin to drop more sharply unless broadcasters and distributors take steps to adapt. The implications may be sobering for broadcasters in many countries: While this particular report is based on data from the United Kingdom, data from other markets shows similar trends.

Focusing on antenna TV specifically, its surprisingly strong performance holds some interesting angles for broadcasters. One might assume that broadcasters would be indifferent to whether a viewer watches TV via an antenna or a pay-TV distribution mechanism, such as cable. As long as they are watching, and the broadcaster can charge advertisers for those eyeballs, who cares how the content is delivered? In fact, since ad skipping is likely less common on antenna TV, one might think that broadcasters would be pleased by antenna TV viewership growth. The reality is more nuanced. Prior to 1992, at least in the United states, broadcasters would indeed have had reason to celebrate antenna TV’s resilience. But since then, in the United States as well as other countries, distributors have been paying broadcasters retransmission consent fees. These fees added up to an estimated US$11.7 billion in 2019 in the United States, up 11 percent from 2018.51 Thus, in countries where retransmission consent fees are material, a shift to antenna TV is better for broadcasters than losing viewers to cord-cutting entirely, but it is a mixed blessing. In countries without those fees, however, antenna TV is an absolutely good thing for broadcasters.

Antenna TV’s resilience shows that up to 2 billion viewers worldwide are willing to make a deal: they will watch some commercials (sometimes a lot of commercials) in exchange for free TV. The willingness to do this is not confined to antennas and terrestrial broadcasts. With the growth of AVOD, we expect hundreds of millions of viewers in 2020 to make the same deal, willing to watch some percentage of advertising content in exchange for free, or at least discounted, quality video entertainment.52

Are all viewers willing to make that deal? Obviously not. As we described in 2018, about 10 percent of “adlergic” North American (American and Canadian) adults block ads in four or more different ways.53 A subsequent survey in Turkey found that about 10 percent of adults there showed the same pattern, which suggests an adlergic population in the developing world as well. In all three countries, the percentage of individuals showing adlergic behavior was higher among young people, those with jobs, and those with higher incomes or more education. When it came to video sources, about half of the US study’s respondents who subscribed to SVOD services, such as Netflix, said that their ad-free nature was one of the reasons they subscribed; just under 10 percent said it was the main reason they subscribed.

Based on all this, it looks like the future of TV will contain a mix of business models. Some TV watchers—about a tenth of the population in developed countries—utterly refuse to watch ads, and will be willing to pay for the privilege. Others, who are willing to watch many ads but want to pay nothing on an ongoing basis, will watch only antenna TV. This latter group likely represents another tenth of the population in North America, but it is higher or much higher almost everywhere else. The expected number of antenna TV viewers varies considerably across regions and among countries within a region: for instance, the gap between the top and bottom antenna TV–watching countries in Europe is greater than 90 percent. And then there are the rest of us: the 80 percent of TV watchers who fall in between those two extremes, paying varying monthly fees and watching varying amounts of ads.

Don’t start counting that second digital dividend quite yet

Oddly, antenna TV’s continuing popularity may have its biggest impact, not on the TV or advertising industries, but on wireless telecommunications companies, regulators, and governments. Perhaps due to the lack of a global figure for antenna TV viewers, it has been widely assumed that, although perhaps a few people still watched using antennas, the number was small and would (relatively) soon approach zero. At that point, it was thought, the frequencies used for terrestrial broadcast could be reassigned. Switzerland has already announced that it is doing so, and some articles speculate that the rest of Europe could follow in the next 10 to 15 years.54 But can the rest of the world follow suit?

It’s not a trivial question. The frequencies used for UHF TV stations in the Americas, between 470 and 890 MHz,55 have many desirable characteristics: They can travel nearly 100 kilometers (depending on power and broadcast tower height), and they pass through trees and most building materials easily, assuring good reception as long as there wasn’t a mountain in the way. These attributes are ideal for transmitting TV signals … or any other kind of radio signal, for that matter.

Digital broadcasting was an amazing win/win transition. A digital signal was better than analog, had less interference and static, and could support high-definition images rather than standard, all using a narrower chunk of spectrum than analog. The TV industry’s conversion from analog transmission to digital (and their corresponding shutdown of analog transmission) not only gave consumers better TV, but also freed up hundreds of megahertz of desirable “beachfront” spectrum. Governments were then able to reallocate this spectrum, mostly to mobile network operators, raising billions of dollars via spectrum auctions in the process. For their part, operators using these frequencies were able to improve coverage and higher data transmission speeds. These gains, which were not small, are referred to as the “digital dividend.” Among other things, the digital dividend contributed an estimated US$15 billion to the Latin American economy alone,56 while spectrum auctions raised $20 billion in the United States, $4 billion in Germany, and tens of billions more in the rest of the world.57

The potential gains for operators and governments would likely be just as large if terrestrial digital transmission goes away. But will it ever happen? It can and will in Switzerland, where only 1.9 percent of the population (about 64,000 people) still watch TV via an antenna. But with half of all TV viewers around the world watching at least some TV using an antenna, broadcasters aren’t going to want to hand over the spectrum they use for those broadcasts to governments, and then to operators, anytime soon. A second digital dividend looks anything but imminent.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

The ears have it: The rise of audiobooks and podcasting Article5 years ago

-

Robots on the move: Professional service robots set for double-digit growth Article5 years ago

-

Bringing AI to the device: Edge AI chips come into their own Article5 years ago

-

Private 5G networks: Enterprise untethered Article5 years ago