The Power of Zoom has been saved

The Power of Zoom Transforming government through location intelligence

14 February 2013

- Anesa “Nes” Diaz-Uda, Joe Leinbach

When location data is coupled with other online resources and expertise, every point on the map can provide a historical and predictive perspective that can aid government in complex policymaking.

The power of zoom represents an evolution in the way government sees and interacts with the world. When location data is coupled with existing government data and expertise, every point on the map can provide historical and predictive perspective to inform complex policy decisions. The map itself has been transformed from a static picture to a living platform for shared decision making and real-time collaboration, focusing the energy of the crowd and empowering government and citizens to work together to respond quickly to challenges at any scale.

Government is the original place-based thinker. The lives of citizens have always been tied to their location—where food was grown, how shared resources were managed, and what threats to health and safety had to be monitored and addressed. Today, the nation is still divided into municipalities, cities, and states, but it has grown to over 300 million “mobile” citizens. Governments continue to rely on traditional geopolitical borders to frame the way their agencies understand public policy problems and accordingly, how they deliver services. But borders don’t always tell the complete story. How can government agencies understand the challenges, tailor services, and measure outcomes at such scale and complexity?

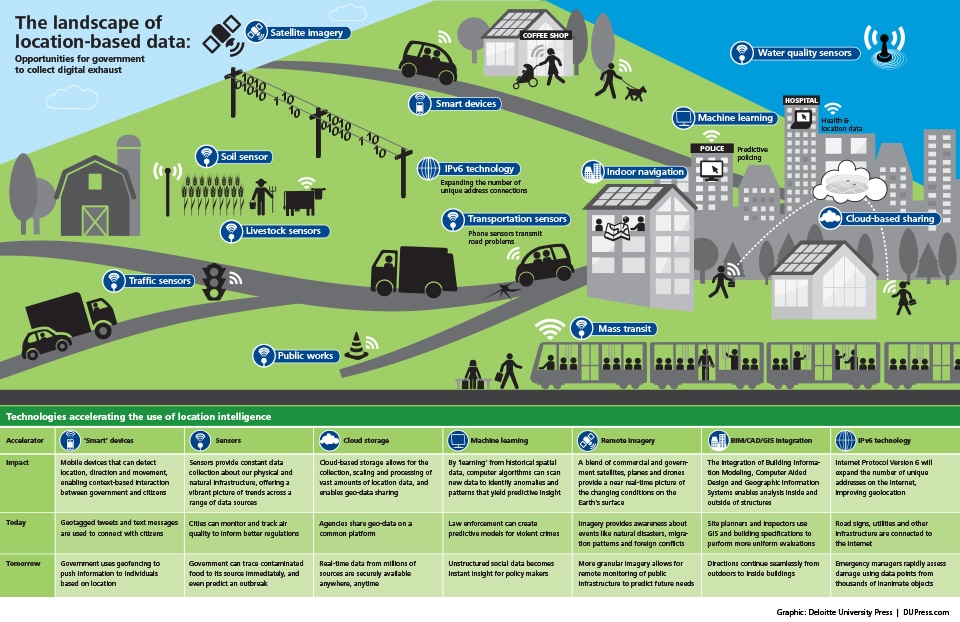

Place is again the answer. With the convergence of emerging geospatial technologies and the increasing wealth of location data provided daily by smartphones and sensors embedded in everything from buildings to buses—the “digital exhaust” created as a byproduct of our daily lives—government can pursue new models for delivering public services, better understand the challenges of diverse communities across the nation, and design more effective solutions. There is an opportunity for citizens to share and receive information customized not only to who they are, but where they are—creating a new paradigm for how government can understand and serve the public.

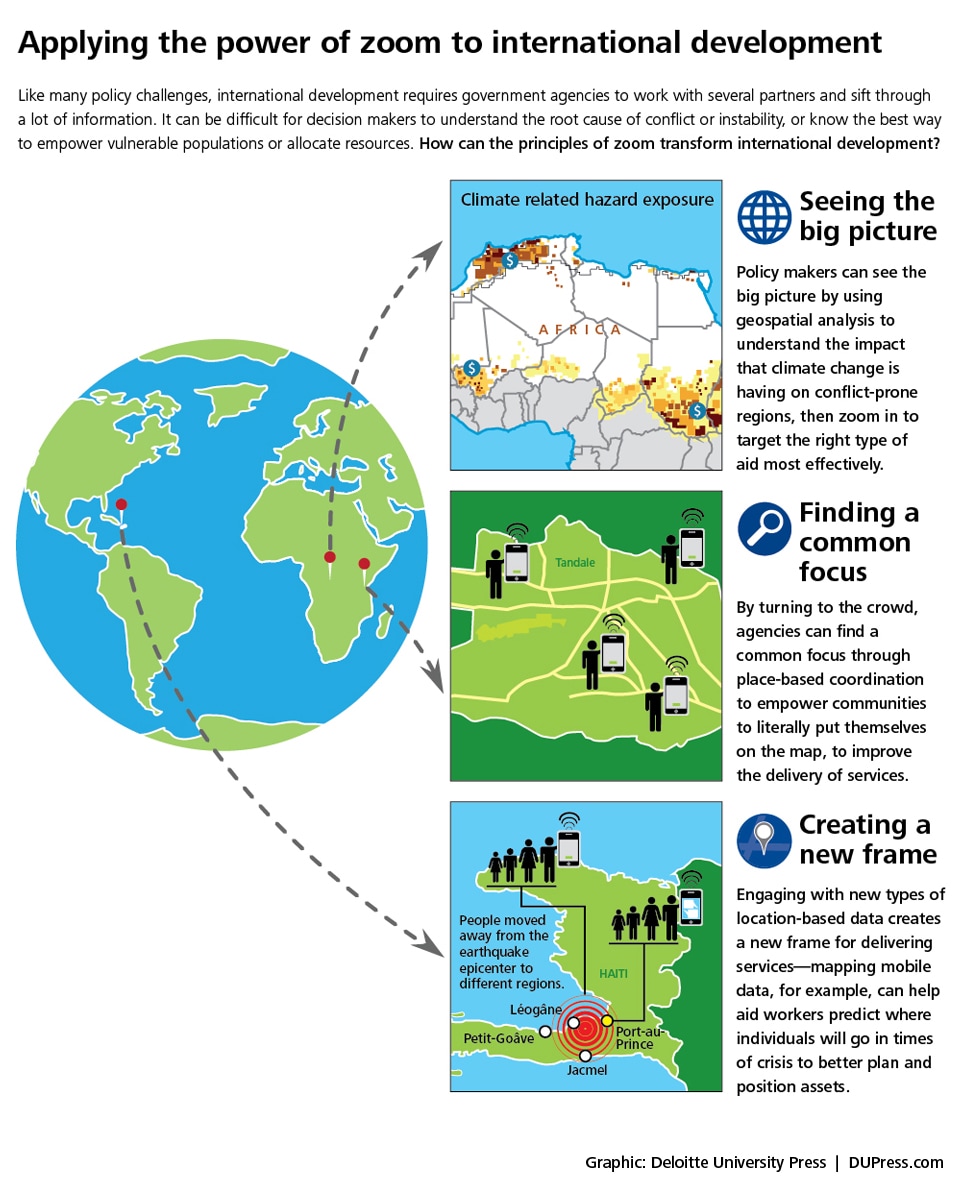

This report describes how governments can apply the following principles of zoom to transform the way they solve problems:

- Seeing the big picture. Geospatial analysis can be a powerful tool for policy makers, allowing them to interpret disparate and complex data through simple, effective visualizations. The context of place creates an instant connection among layers of data, helping agencies zoom in on the details that matter, or zoom out to add context. By harnessing place as a comparison tool, policy makers can sift through the multiple plausible causes of a particular issue, like poor health outcomes, and better understand the challenges unique to a specific place.

- Finding a common focus. The universal language of location allows diverse stakeholders to share data, imagery, geo-coded SMS messages, and traditional geographic information systems—in a way everyone can understand. Through the common lens of location, government can become a platform for information sharing across agencies, sectors, and levels of government to focus policymaking and tap into the power of the crowd.

- Creating a new frame. In the commercial world, industry leaders are racing to develop new products that tailor information based on a user’s location and context. Government, too, can use location intelligence to design new models for delivering services, translating digital exhaust into value to simplify citizens’ interactions with government services and improve the customer experience. Similarly, agencies can use data from physical assets like vehicles, buildings, and devices to increase operating efficiency and better track and monitor performance.

Government can start moving forward with the rapidly evolving capabilities of location intelligence by assembling the geo-data already within agencies, and looking beyond program or agency boundaries to the private sector and citizens. Agencies can address issues of citizen and employee privacy by framing services around value, adapting existing privacy frameworks to make sure that protections are adequate, and ensuring the collection and use of location data are transparent.

Place plays a significant role in defining who we are. The power of zoom helps government get back to basics, empowering public servants and the community to work together to solve the most pressing problems at any scale—from issues affecting local communities to those that transcend national borders.

Introduction

We live in an uncertain world, but for many people there’s at least one constant—a hot cup of coffee to start the morning. At the corner diner, in the lobby of an office building or at a drive-thru window, that first cup gives us the boost we need to take on the day. And after that cup is empty, we rarely give a second thought to where it’s headed afterward.

Carlo Ratti, director of the MIT SENSEable City Lab, wanted to find out. So his team of researchers asked—where does our recycling go? How far does it travel? With several volunteers, the team launched the Trash Track project, attaching location sensors to more than 3,000 pieces of trash in Seattle. Then, they waited. And waited.

As the weeks and months passed, an MIT server tracked each object’s path across the country. Interestingly, more than 75 percent of the objects reached a recycling facility, well above the national average of 34 percent.1 But for some, such as a printer cartridge that traveled almost 4,000 miles to its final resting place in Florida, the energy spent in transit probably exceeded the environmental benefit of recycling. “Trash disposal is one of today’s most pressing issues,” said Ratti. “Our objective with this project is to reveal the disposal process of everyday objects, as well as highlight potential inefficiencies in today’s recycling and sanitation systems.”2

MIT Trash Track visualization3

MIT Trash Track visualization3

What are the implications for government when we can use technology to see what was once invisible? When sensors are so cheap, we can literally throw them away? For the Trash Track participants, it meant that they could gather and use data in a way few would have thought possible, bringing attention to an issue many of us rarely think about and crafting a compelling visual that couldn’t be ignored. “

As the location reports from the tracked objects started coming in, we were fascinated to see an invisible infrastructure unfolding,” said Dietmar Offenhuber, Trash Track project leader. “The extent and complexity of the network of waste trajectories was quite unexpected.”4

The increasing wealth of data provided daily by smartphones, physical sensors, and the Internet—the “digital exhaust” created as a byproduct of our daily lives—has given rise to new models and opportunities for government to better understand its challenges and design more effective solutions. When location data is coupled with other online resources, every point on the map can provide valuable intelligence. Emerging geospatial technologies allow us to quickly visualize and find meaning in billions of transactions, tweets, check-ins, and geotagged photos. When combined with existing government data and expertise, this intelligence can, in turn, help us redefine the way we see and understand the world, creating digital pictures of the ebb and flow of our societies. A place is no longer simply a point on a map or a political jurisdiction, but a living, evolving hub of information, a convergence of digital and physical worlds. For government, this new ability to visualize and understand trends at any location offers a historical and predictive perspective for policymaking to inform complex decisions about the distribution of resources or the design and delivery of public services. But the new technology of place can provide far more. The map itself has been transformed from a static picture to a living platform for shared decision making and real-time collaboration, adding a new dimension to the delivery of public services. Location-based data can be used to focus the energy of the crowd, empowering government and citizens to work together to respond quickly to local disasters or tackle national problems.

Geospatial analytics: Statistical analysis of data elements that can be tied to a location on, above or below the earth’s surface

Location-based services: Programs or services (such as mobile apps) that deliver information concerning an individual’s specific location

Digital exhaust: Data generated by electronic devices (such as smartphones and credit card purchases) and physical sensors (such as digital wind and temperature gauges and traffic cameras) that include a location

We call this the power of zoom, and it represents an evolution in the way government sees and interacts with the world. The convergence of traditional geospatial technologies—once the province of computer scientists and geographers—and location-based services—which allow individuals to receive personalized information that is relevant to their location at any given point in time on their mobile devices—can allow us to visualize the choices we make, the relationships we create, and the impacts of our actions. As is often the case with new technologies, some find these capabilities off-putting or even sinister. But they don’t have to be. What some would describe impersonally as “big data”, we see as just the opposite. Location-based data can be used to create policy at a human scale, allowing decision makers to “zoom” in to understand events in our communities and zoom out for broader context at the national and even global scale. By coupling its responsibilities with advances in geospatial, sensor, and location-based technologies, government can use the power of zoomto overcome a wide variety of challenges. The report describes how governments can apply the principles of zoom to transform the way they solve problems by:

- Seeing the big picture—using geospatial visualization and location analytics to inform better policymaking

- Finding a common lens—employing place-based analysis and geospatial collaboration tools to increase the effectiveness of shared assets and improve their coordination

- Creating a new frame—examining public- and private-sector approaches to the use of digital exhaust to develop location-intelligent services, greatly improving the cost-effectiveness of traditional public services

We will also see how agencies can put zoom into practice by tapping into ecosystems of innovators inside and outside of government, considering the challenges of privacy, and finding ways to deliver better value in exchange for public participation.

Seeing the big picture: Better policymaking with geospatial analytics

“When you start to relate activities and people and places to each other, you see patterns—and that’s one of the critical things, so we can start to anticipate problems before they arise, and have more of a set of tools we can offer to decision makers.”—Keith Barber, Director of the National System for Geospatial Intelligence Expeditionary Architecture Integrated Program Office, National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

In 1854, an outbreak of cholera swept through London’s Soho district, killing hundreds. An anesthesiologist named John Snow suspected contaminated water might be the cause of the disease, but in the absence of any understanding of germ theory, prevailing expertise blamed “bad air.” Looking for evidence, Snow literally mapped the location of individuals who died, and observed that they were mostly clustered around the intersection of Broad and Cambridge Streets, the site of the now-infamous Broad Street pump.

John Snow’s map of cholera deaths near the Broad Street Pump6

Google/Doctors Without Borders map of near real-time cholera cases in Haiti7

Further investigation revealed that Broad Street’s water came from a stretch of the Thames contaminated with sewage, which we now understand to be the principal means of cholera transmission. Snow’s arguments led to the removal of the pump handle—and a precipitous drop in the rate of cholera infection. 8

Almost 160 years later, the international medical relief organization Doctors Without Borders worked with Google’s Crisis Response team to address the spread of cholera among survivors of the massive earthquake in Haiti. By mapping the water system along with patients’ neighborhood of origin, analysts visualized where outbreaks were happening in near real-time, allowing Doctors Without Borders to persuade response coordinators to prioritize repair areas where outbreaks were occurring.910

According to deputy head of mission in Haiti Ivan Gayton, “Maps can be a powerful advocacy tool. You can convince policymakers to take action by showing them data in a visual, visceral way.”11

Geospatial analysis is far more than dots on a map. It can be a powerful tool for policymakers, allowing them to interpret disparate and complex data through simple, effective visualizations. The context of place creates an instant connection among layers of data, prompting users to dig deeper and come up with questions they might have never thought to ask. Public policy problems often involve multiple layers of complexity. What causes banks to fail in one region and not in another? Where should we send police officers to stop a wave of gang violence? Why is a certain group of people afflicted with a disease, while only a few miles away no one is sick?

Geospatial visualization and analytics move policy analysis out of spreadsheets and onto the map, allowing government to zoom in and out, seeing multiple factors at a single glance, and better understanding how different characteristics relate to one other—and to place.

Four uses for geospatial analytics:

Harness place as a comparative tool

Drive accountability

Move from prescription to prediction

Rethink boundaries

1. Harness place as a comparative tool

As with the London cholera outbreak, prevailing wisdom doesn’t always reveal the root cause of a problem. Geospatial visualization helps us sift through multiple, plausible causes of some of the toughest public policy problems, seeing surprising and unexpected correlations among different information.

If some characteristics are held constant, such as demographics, per capita funding, and regulatory structures, place can provide a strong base for comparison. Policymakers can zoom in to see why some programs and projects thrive in one place and fail elsewhere. Consider basic environmental issues; we live under the same clean air and water laws, yet environmental protection obviously is not uniformly effective across the nation. Policymakers can use geospatial tools to identify and mitigate disproportionately adverse environmental impacts on minority and low- income populations.12

Create immediate context. Maps provide a powerful way to organize massive amounts of data around a common attribute or location, and provide a starting point for conversation about many tough decisions with citizens and other government stakeholders. In New York City, the Mayor’s Office and Columbia University partnered to develop a digital model that shows how practically every building in the city consumes energy, distinguishing among heating, lighting, and other purposes.13

Seeing the relationship between energy use and community design can help policymakers and the public alike understand how energy usage relates to social and environmental factors. Such information can help property managers and private owners share resources among buildings or blocks, and enable city leaders to target the best locations for different types of alternative energy generation.

Highlight differences to drive innovation. Place-based comparisons are particularly useful to showcase the variance in factors such as availability, cost, and the quality of services. Healthcare is ripe for this kind of analysis. Our access to affordable health care, treatment outcomes, and even patterns of disease vary widely by geographic location, even across relatively similar regions.

The Dartmouth Atlas Project displays health data across 306 US hospital referral regions on factors involving costs and quality, allowing users to question and explore geographic variations in health statistics.14

Elements of place-based comparison

- Demographics: Age, gender, income

- Infrastructure: Transit, land use

- Geography: Natural resources, threats

- Public assets: Government facilities, resources

- Administration: Regulations, tax code

For example, what drives regional variations in the cost of prescription drugs purchased through Medicare? Geographic analysis indicates that these variations are due primarily to regional restrictions on the use of generic drugs. By easing restrictions on generic drugs in high-cost areas, policy makers can reduce overall Medicare costs.15

Find mismatches faster. The misalignment of the supply and demand for government services is perhaps inevitable, given competing priorities, political mandates, and population shifts.16 But such misalignment isn’t always readily apparent, and what begins as a small problem may not be noticed until a major investment is required to fix it. A study of local health departments in several states found that low-cost, publicly available geographic information systems (GIS) data could allow their staff to compare population distributions with the location of health facilities, identifying gaps between programs and community health needs.17

See the big picture to monitor change. Some policy challenges require us to zoom out and consider regional or environmental problems. For example, researchers from the Climate Change and African Political Stability Program (CCAPS) at the University of Texas at Austin are using geospatial analysis to identify and possibly mitigate political instability that may result from climate change. By layering climate, population, conflict, and foreign aid data on a map, policymakers can better predict the regions most vulnerable to climate change, and understand how to target aid more effectively.18

“Climate change poses an enormous threat to the livelihoods of millions of Africans. The level of risk, however, is not evenly spread and certainly doesn’t respect national boundaries. To ask critical questions about how development assistance can reduce vulnerability, you need hyperlocal data on climate and also on aid-funded interventions. This is what the new CCAPS mapping tool shows in a digestible, interactive way.”—Jean-Louis Sarbib, CEO, Development Gateway

2. Drive accountability

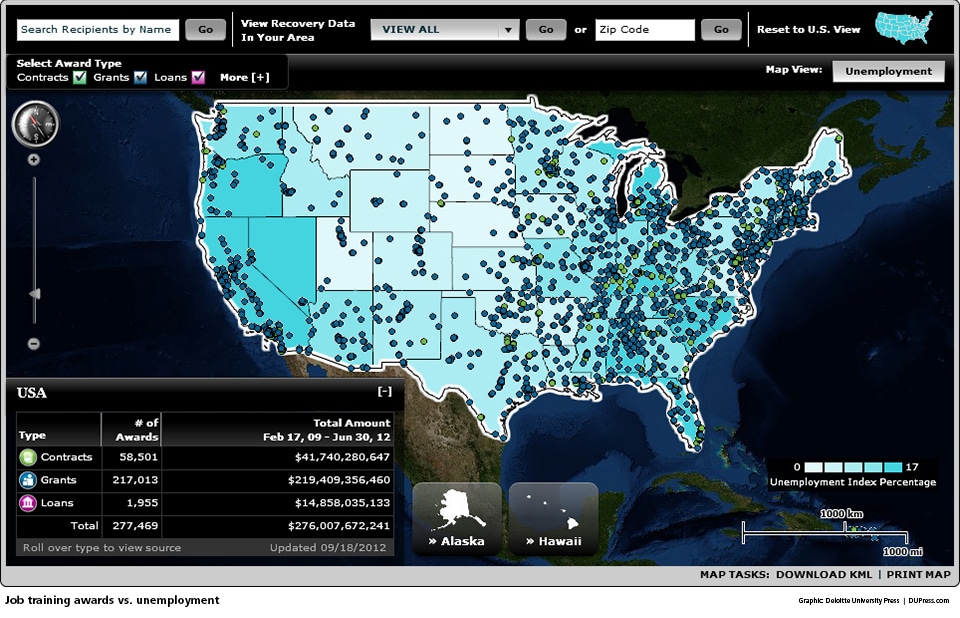

The open data movement is fostering more accountability in government at all levels, by enabling citizens to ask informed questions about decision making and performance. Geospatial platforms are especially useful in this arena, highlighting “who and where” impacts to defend or oppose current policy—or expose waste or political favoritism. One example of this is Recovery.gov, an online public platform that tracks where money from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was distributed in a simple visual format.20

The platform not only helped inform the public, but also created an expectation of accountability for the ultimate recipients of ARRA funds. Grantees knew their information would be published as soon as it was collected, giving them an incentive to provide more precise data in a timely fashion.

White House chief administrator of ARRA Ed DeSeve noted, “Through this platform we were able to bring together data from 200 business units in 40 agencies across 50 states, and present it in a way that speaks to people interested in a specific geographic area. It was also helpful for a defensive posture—we were able to respond to critics, minimize fraud and geo-audit recipients.”

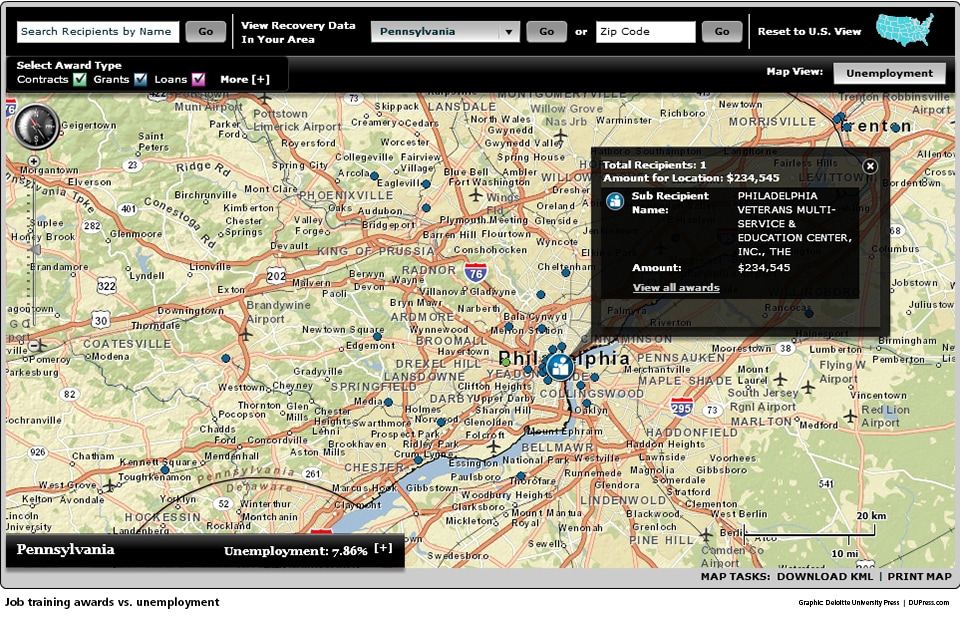

Using Recovery.gov to identify and compare funding for job training programs by states with the highest unemployment rates21

Using Recovery.gov to identify and compare funding for job training programs by states with the highest unemployment rates21

3. Move from prescription to prediction

One of the most fascinating aspects of location-based data is the stability and predictability of patterns that can be mined from seemingly unrelated data. A cluster of random dots on a map can represent a daily transportation route, the most popular dating spots, or the neighborhoods with the highest concentration of gang violence. These patterns, analyzed over time and in large numbers, begin to allow for informed predictions of behaviors and events. For government, this analytical capability enables better resource allocation and more effective outcomes.22

Chicago’s chief data officer Brett Goldstein is attempting to prevent violent crimes in the city before they happen. Goldstein’s predictive analytics unit runs spatial algorithms on 911 call data to identify where and when violent crimes or robberies are most likely to happen. As Goldstein puts it, “Different parts of the city behave in predictable ways—beyond a city of neighborhoods, Chicago is a city of blocks, and these blocks are part of an ecosystem. We can create mathematical models with this ecosystem that are statistically significant, and give us leading indicators for when an expected level of a given behavior is likely to happen.”23

Advances in predictive analytics using location-based data are emerging across several frontiers. Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University are developing a statistical tool that combines electronic health records, tweets, and other information with spatial analysis, to translate large amounts of social data into patterns that could identify epidemics or other health trends.24 Similarly, a UK team found that by cross-referencing an individual’s location data with that of their friends, the team was able to predict where that person would be 24 hours later, within 20 meters.25

4. Rethink boundaries

Governments must look beyond traditional jurisdiction lines to address some of today’s most complex policy challenges. Environmental effects, for instance, pay no attention to political boundaries. Transportation networks cross state lines, and many people may live in one congressional district yet work in another. Our social networks are even less constrained, with Facebook and YouTube connecting individuals around the world to act upon a single issue.

Geospatial analysis not only helps us examine issues within traditional, geopolitical boundaries, but also those that blur the lines, encouraging decision makers to consider social as well as political characteristics and rethink the role of boundaries in policymaking.

Understanding how people move, where they interact, and what services they need allows government to rethink several basic dimensions of its role:

- Resource allocation—where to deploy assets, personnel, or funding for health, transport, and economic development

- Communication—how to reach a target demographic concerning a particular issue such as obesity, or in the event of an emergency

- Coordination—when to combine resources with other agencies or private or nonprofit entities to aid a specific population

In the commercial world, particularly for retailers, this sort of analysis is critical. The ideal site for a new store relies far more on purchasing power, customer drive times, and consumer preferences than political boundaries. It also broadens the frame of reference from traditional demographic characteristics such as gender, age, and income to consider “tribes” that share common behaviors and decision patterns.

Understand shared characteristics. The practice of identifying groups with shared characteristics based on their location is a technique called micro-segmentation, which breaks down 70,000+ US Census tracts into several consumer segments. Esri, one company with such data, defines these segments with catchy names such as “wealthy seaboard suburbs,” “rustbelt retirees,” and “city strivers.”26 Such designations help retailers target their core customers and ensure that their target demographic finds their locations and products. For example, Internet giant eBay has divided its Australian market into 15 “geoTribes” to target its online advertising.27

See the social connections. Researchers at Carnegie Mellon have added social media to the mix, mining data from 18 million Foursquare check-ins to redraw neighborhoods in several cities based on check-in patterns.28 Branding these areas as “livehoods,” the team hopes its information can be used to improve city planning, transportation services, and public health surveillance.29

Problems addressed with geospatial analytics:

- Make sense of scale and complexity. In the last 30 years, the US population has risen by more than 40 percent to more than 300 million people, straining policies and infrastructure.30 Geospatial analytics can help government to understand the complex relationships underlying policy issues, and use place as a comparative tool to gain understanding from disparate data sources.

- Support more open and accountable government. Americans’ trust in government to solve big problems is at an all-time low, due in part to a lack of evidence as to whether current policies are working.31 By using geospatial platforms to share government data, agencies can connect with the public in a more transparent manner.

- Move beyond assumptions and generalizations. Agencies’ missions have been stretched by shifting priorities, as governments struggle to get in front of key challenges. With place-based thinking, organizations can use the predictive power of spatial data to overcome emerging challenges.

- Look beyond “borders” to increase collaboration. Today’s complex challenges are not neatly contained within county or state lines. Geospatial analysis can help government to better visualize mismatches between the supply of public services and citizen demand, and to rethink borders to create a richer context for designing policy interventions.32

Finding a common focus: Improving program delivery with place-based collaboration

“Place-based management promotes decision making that isn’t bound by programs, or funding streams, or departmental structures, but brings all of those together in the same room to embrace context and leverage the resources available across the board.”—Raphael Bostic, former Deputy Administrator, US Department of Housing and Urban Development

Many are familiar with Ushahidi, the online mapping platform that crowdsources information, and its role in the response to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. What is unique about this case, however, is that it demonstrates how crowdsourced mapping platforms have permanently changed the way in which governments and people can interact in times of crisis.

Port-au-Prince on OpenStreetMap before the earthquake42

Port-au-Prince on OpenStreetMap before the earthquake42

Port-au-Prince on OpenStreetMap after the earthquake

Port-au-Prince on OpenStreetMap after the earthquake

Within days of the earthquake, and with little assistance from any government, a text message from a survivor could be geo-located, translated from Haitian Creole, put on the map via the Ushahidi crisis-mapping team, and routed to first responders in less than 10 minutes.43 Within the first week the team received more than 20,000 messages that were filtered and mapped along with the locations of makeshift hospitals, shelters, and potable water sources. Ten days after the earthquake, US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administrator Craig Fugate tweeted that Ushahidi’s map was the most comprehensive and up-to-date information available to the humanitarian community.44

At the same time, other volunteers used before-and-after satellite imagery freely provided by commercial vendors to make hundreds of edits to OpenStreetMap, a free and open wiki-style mapping platform, literally putting Port-au-Prince on the map (see inset).45 In a matter of hours, the city was transformed from a couple of highways to a thicket of narrow streets and communities, creating the baseline layer for sharing the Ushahidi information.46 By the time urban search and rescue teams arrived from the United States, one responder from Fairfax County, Virginia, commented that he only wished he had a way to express how valuable this data is for responders.47

The Haiti response demonstrated the power of place-based information. The Ushahidi map was developed quickly, outside the administrative barriers of government, and took advantage of the skills and passion of volunteers. The universal language of location allowed diverse stakeholders to share data, imagery, geo-coded SMS messages, and traditional GIS—in a way everyone could understand. Perhaps even more significantly, Ushahidi allowed the survivors to use their mobile devices to fill in the gaps and define the areas of greatest need across a large geographic area, not just a couple of blocks. Geospatial data also made crowdsourced information easier to validate; if several voices called for help in a specific area and reported the same details, there probably was a significant need there. In fact, Ushahidi data since has become part of the United Nations’ official situational reports.48 The usefulness of these technologies, however, extends well beyond crisis scenarios. The intersection of sensor technology, imagery, data mining, and web-based platforms creates new opportunities for government to share place-based information among agencies and with the public and other stakeholders across a wide range of policy issues.49 At this intersection lies tremendous opportunity for collaboration where government itself can be used as a platform and its employees are perpetually location-aware.

Four uses for place-based collaboration:

Use government as a platform

Focus the power of the crowd

Allocate resources with location data

Use location intelligence in daily operations

1. Use government as a platform50

Though many government agencies may take longer to adapt to new technologies or opportunities, they are uniquely poised to marshal and coordinate significant amounts of data, resources, and expertise. The ubiquity of mobile devices means that maps and contextual data will become a fundamental unit for information sharing.51 To accelerate the delivery of smarter, faster (and possibly cheaper) services, government should become a platform for information sharing between internal and external stakeholders, with geospatial data as the centerpiece.

Reduce barriers with a “geo-cloud.” Effective platforms provide data to many audiences and are scalable to accommodate new information and technologies. Geospatial data stored in the cloud can allow government agencies to better understand what their counterparts are doing for a specific population or target area, and can help pave the way for better coordination of programs and services. Cloud-based storage also can incorporate non-governmental data sets; for example, a health and human services agency could combine its own historical health-related data with housing statistics from another agency, and then layer in geotagged social media data and news reports to pinpoint where the next round of flu is most likely to emerge.

The federal government has taken steps towards creating a shared platform for geospatial data. In the wake of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, federal, state, and local agencies learned how difficult it was to share geospatial data across their servers and maps. To enable such collaboration, the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) is working to create a one-stop portal for mapping efforts, offering a web-based interface that allows users to share maps and data layers with one other, as well as with the public.52

Encourage external innovators to build on government geo-data. Private citizens and organizations should be encouraged to add details or build useful apps for government geo-platforms. Consider Foursquare’s new Connected Apps framework, which helps third parties add information on top of check-in data. For example, if you check in at a restaurant, a diet-related app might suggest appropriate meals, while a social app could tell you if any of your friends have eaten there, and if they left any comments.53 The parallel for government is obvious; many apps have already been built with government data, from health service locators to navigational aids for national parks.54

The city of Chicago, for instance, added detail to the US Department of Agriculture’s Food Desert Locator map, which shows areas with limited access to healthy foods. By layering city-level data down to the block level, policy makers can pinpoint specific underserved neighborhoods and use the data to negotiate with grocery stores regarding site selection, or strategically locate farmers’ markets in areas that need them most.55

2. Focus the power of the crowd

While geospatial analysis may have once been the province of internal experts within government, agencies can focus on building and sustaining a community of developers and contributors outside government’s walls.

Engage the “geo crowd.” One way to build such a community is to launch a competition or challenge that is fun for participants while furthering a larger public policy goal. Policymakers may be surprised by how willing citizens are to lend their time to mapping projects, if the process is enjoyable.

For example, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) recently turned to the crowd to geocode international loan guarantee information. A group of volunteers from the online mapping community rose to the challenge, resulting in the release of data on more than 117,000 loan records at no additional cost to the agency.56 Motivated by passion for USAID’s mission and a desire to make the data available for public use, these individuals turned their private time into public value. NASA also recently experimented with crowdsourcing, using “gamification” to reward participants with points or badges for identifying scientifically relevant content on maps of the sea floor, a process that might be used in the future to quickly map features of asteroids or planets, including our own.57

Such challenges reveal the power of place to engage the public. Connection to the agency’s mission, a particular geographic area, or a specific population can turn activities that are fun and fulfilling for citizens into meaningful contributions for government.

Use commercial partners. The private sector can play a valuable role as a data provider, and as a partner in solving public-sector challenges. The employee and store location networks of the nation’s largest corporations represent a wealth of potential sensor data, as does the sophisticated asset intelligence that informs modern supply-chain operations and logistics.

FEMA has begun embedding executives from large retailers like Target and Walmart into its national operations and response center for 90-day periods, to facilitate information sharing.58 For example, retailers can share what stores are open or closed during a disaster, or show inventory levels of certain products such as plywood in advance of a hurricane to understand how people are preparing, or what needs will be greatest after the event. FEMA hopes eventually to develop a map of major retailers’ status across the country, and share this information with state and local response teams during disasters.

Empower the most vulnerable. The crowd can make huge impacts with geospatial analysis, without expensive technology. Tandale is a slum of between 50,000 and 70,000 people crammed into less than one square mile on the periphery of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Until very recently, it literally wasn’t even on the map. Over the course of two months, a team from the World Bank trained community members to use inexpensive, global positioning system (GPS)-enabled phones to photograph and geotag places of interest for the community (such as public toilets, water sources, medical bases, and the elementary school) and upload the data to OpenStreetMap.59

Equipped with this infrastructure data, residents of Tandale are currently in conversations with their local government to garner additional public services. In addition, the community set up a Ushahidi-based site, Ramani Tandale, which allows residents to report flooding, broken street lamps, and other issues.60

3. Allocate resources with location data

A more traditional role for geospatial analysis in government has been in deciding where to locate fixed resources such as transportation systems, hospitals, or public spaces like parks and playgrounds. Much of our current infrastructure, however, is located based on decisions made decades ago. Today, we can take advantage of geospatial analysis to make smarter decisions about where and how to invest scarce resources in ways that are sustainable and supported by the public.

Use complex technologies to enable simple analyses. New geospatial tools allow for more sophisticated analyses, using multiple layers of data to compare potential scenarios and make decisions that consider the impact to diverse stakeholders and constituencies.

One example is Azavea, a geospatial software firm that develops collaborative, open-source applications to help decision makers and the public visualize and understand the impact of public policy decisions.61 From collaborative political redistricting to targeting the optimal location for new urban street trees, these types of emerging geospatial solutions can quickly crunch thousands of variables in a way that many stakeholders can understand. Citizens and policy makers are empowered to “drag and drop” each new idea to assess the impact, making resource allocation decisions more collaborative and data-driven than ever before.

“ [S]ensors, smartphones, tablets and collaboration platforms will be as transformative of business in the 2010s as the Internet and the Web browser were in the 1990s. To cite two far-reaching examples, electronic medical records are changing the way hospitals conduct healthcare, while smart meters are transforming the way that utilities track and manage demand for electricity.”—Forrester report, “Smart Computing Connects CIOs With The Business,” March 28, 2012

4. Use location intelligence in daily operations

The usefulness of location intelligence isn’t limited to strategic decision making. Place-based information can be incorporated into daily government operations to improve the delivery of programs and services. Take the case of a safety inspector:

- Contextual data—Via her smartphone or tablet, the inspector is prepared for her daily site visits with directions, overview information, and related community statistics. For each site, she has profiles of the individuals she will meet, verified by whether they have checked into work that morning.

- Location-based notation—Upon arrival, push notifications provide notes from previous inspections about particular problem areas at each site, including pictures and resulting action items assigned to the facility.

- Augmented reality and internal navigation—As she walks through a site, her device alerts her to areas tagged as problems in the past, indicates that this particular site seems to lack necessary supplies, and offers data about conditions in similar facilities to help start conversations with individuals at the site.

This scenario isn’t at all far from reality. The US Department of Veterans Affairs is in the process of installing a real-time location system for its hospital assets ranging from surgical instruments to patients’ beds, designed to improve efficiency and patient safety. Through the use of radio frequency identification (RFID) tags and barcodes, employees can locate equipment in real-time, monitor inventory levels, and ensure sensitive equipment is being housed within the right temperature and humidity ranges.63

Problems addressed with place-based collaboration

- Use location data to address duplication and overlap. Today’s challenges require governments to coordinate and connect services across jurisdictional lines.64 Without such coordination, service delivery can be disjointed, inconsistent, and ineffective. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports often highlight fragmented service delivery due to a lack of common goals or formal data sharing and collaboration agreements.65 Place-based coordination and analysis within a geospatial platform can improve government coordination and make service delivery more efficient and effective.

- Fill in “blind spots” for better decision making. The United States includes more than 3,100 counties and 19,000 municipalities, each with its own unique issues.66 Large federal initiatives may not account for local or regional facts on the ground. Governments can create more effective policies by sharing information through a cloud-based platform, and looking to public and private partners to help fill in the “blind spots” in their analyses.

- Accelerate the collection of useful information. Important decisions should be based on the best available data. Despite the explosion in digital exhaust from the worldwide spread of smartphones, official information can be outdated or take too long to collect and deliver to decision makers. Consider, for instance, that the data used to measure progress toward the UN’s Millennium Development Goals is from 2008 or before, and thus fails to account for the impacts of the global financial crisis. Meaningful geotagged data, assembled by government workers or the affected populations themselves, can accelerate the collection of information needed to support decision making.67

- Move past big data as a buzzword. Data is constantly generated via interactions between government and citizens—filling out forms, completing transactions, and conducting site visits are just a few examples. The potential of big data lies in tying all of this information together in a useful way. Because each interaction possesses location metadata (such as addresses and coordinates), place becomes the lens through which employees can access contextualized real-time information, translating big data from zeros and ones into better quality services.

The landscape of location-based data: Opportunities for government to collect digital exhaust

The landscape of location-based data: Opportunities for government to collect digital exhaust

Creating a new frame: New models of delivery using location-based data

“It’s not only infrastructure and centralized sensing networks—the greatest sensor network out there is the people themselves. It’s some kind of ambient sensing, the wisdom of the crowd. You don’t need to call 311, you just have to complain about it.”—John Tolva, Chief Technology Officer, City of Chicago

Previously, we observed how digital exhaust assisted recovery efforts in Haiti, both through visualization and collaboration. But there is a third aspect to this example—the power of digital signals as a force multiplier, to make big impacts even with relatively small amounts of data.

Several months after the cholera outbreak that followed the Haitian earthquake, a team of health researchers mined Twitter traffic and news stories from the first 100 days after the outbreak to search for correlations with official reports.69 After collecting almost 200,000 tweets and close to 5,000 news reports mentioning cholera in English, French, or Spanish, the team found a strong connection between geolocated chatter about cholera and the actual times and locations of outbreaks.

While official reports took days or weeks, this information could have been available almost immediately.70 “Official case reports have to get verified by hospitals, so it often takes a couple of weeks for that information to be posted and available to health workers,” said Dr. Rumi Chunara, the study’s author and a research fellow at Harvard Medical School. “Informal sources like Twitter are obviously much more real-time.”71

Similarly, another research team tracked the position of 1.9 million cell phones owned by people living in Port-au-Prince, and compared their location 42 days before the quake to 158 days after. The analysis showed that 630,000 people fled, more than 20 percent of the population, closely matching numbers from an official UN survey.72 Through a real-time study during the cholera outbreak, the team was able to show updated population movements within 12 hours. Such data could be used to find survivors and direct resources to where they are needed, and to model how populations react in emergency situations for future responses to humanitarian crises.

Location intelligence can help government understand problems in new ways, and design new models for delivering services that rely on these insights. To take advantage of these capabilities, we must identify and collect new types of spatial data and translate them into useful information. In the commercial world, several industry leaders—Google, Apple, Amazon—are already competing in a location-based “arms race” to develop products tailored to users’ location and context (see inset box).

The public sector can benefit as well. Armed with this additional data, governments can better accomplish their missions, create new models for service delivery, and use the power of the public to develop solutions.

Four ways location-based data can power new models:

Translate signals into value

Gather asset intelligence

Design geo-intelligent programs

Use place-based thinking to redefine “public” services

1. Translate signals into value

The challenge involved in using digital exhaust is to find value within the terabytes of datasets produced every hour. Location analytics offer a means of viewing current trends in real-time, in a way that keeps the public in focus, allows agencies to ask new questions, and begins to yield new insights.

This will become increasingly important as government agencies attempt to “app-ify” their services. For example, the White House’s new Digital Government Strategy directs agencies to optimize certain customer-facing services within six months, and many of them will take the form of mobile apps.73,74

Create a mechanism to collect meta-data. To get the right data into the hands of the public requires government to understand what information it wants and needs. Data sources that public agencies can use include:

- Direct citizen data—Many agency websites already collect web analytics indicating what users are searching for.75 User analytics go a step further to capture where people are located while searching, whether on a computer or mobile device or at a public kiosk. By correlating search data with particular locations, agencies can tailor search results to improve access to their information or services.

- Indirect citizen data—Data from public sources such as social media are publicly available, and in many cases already geolocated. Chicago is looking to Twitter to reinvent the way it identifies problems involving city services. By establishing a “geofence” around parts of the city to focus the intake of social media, analysts can collect data, anonymize identity, and classify the information for action by the appropriate city department. For example, a tweet stating that “on the bus from loop 2 Wrigley and AC has totally died” could trigger a service request to assess and repair the bus’s air conditioning.76

- Employee interaction—Government can reduce the administrative “friction” of manually entering performance data by capturing geotagged reports from government employees as the task is happening. For example, postal delivery drivers can record the most efficient routes or indicate when a property appears vacant.

The location-based “arms race”

The commercial battle for location-based service supremacy is heating up. Apple recently announced its own mapping application for the iPhone and iPad, complete with turn-by-turn navigation from TomTom, replacing a service provided by Google since the release of the first iPhone. There is a strong business case for Apple; other products like Siri would benefit from learning users’ locations, destinations, and local search habits, data currently valued by Google to target advertising. Google responded by releasing its own set of new mapping features, including Google Now, which uses location tracking to anticipate what users might search for (such as transit routes or local dining options), and an updated Google Earth with 3D imagery of major cities that Google collected with its own fleet of planes.

Both giants are primed to invest significant resources in location-based services. By some estimates, Google already spends between $500 million and $1 billion annually on map-related services, up to a fifth of its total R&D budget.77 Other players also are getting involved. Microsoft incorporates mapping and navigation powered by Navteq in its new devices, while Amazon recently acquired a small mapping company for possible inclusion on future Amazon-branded mobile devices.78,79

Each of these forms of data collection is possible today, and new technologies offer the potential for even more detailed reporting. One example is Geoloqi, a platform that blends geofencing, location analytics, and other services to create reports of consumer behavior.80 By framing services around this level of “hyperdetail,” founder Amber Case envisions an easier, more efficient world where the “smartphone becomes a remote control for reality.”81

Consider, for instance, a citizen walking into a post office or approaching an airport security checkpoint and receiving helpful information, such as hours of operation or current wait times, pushed to his or her mobile device without prompting. Through mobile apps and other opt-in services, individuals could receive personally tailored information simply because they’ve entered a “geofence” set up by an agency. Simpler interactions, customized data—these services have the potential to greatly improve the individual’s customer experience with government.

2. Gather asset intelligence

Agencies also can use signals from fixed resources including vehicles, buildings, and other devices and infrastructure to increase operating efficiency and better monitor performance. Advances in RFID and GPS technology have increased resolution to millimeter-level positioning, creating new opportunities for innovation.82 The era of “GPS everywhere” allows agencies to visualize relationships and collect information in previously unimagined ways.

For example, governments can structure agreements with automobile companies to make the roads safer for drivers. Many newer-model cars come fully wired to connect to the Internet, and their manufacturers can, for instance, learn when and where airbags are deployed to determine whether the driver has been in an accident.83 Similarly, transportation officials could mine geotagged antilock brake activation data to better locate roadway signs warning motorists of upcoming hazards, or use in-car navigation systems to alert drivers of upcoming road closures or accidents.84 In fact, Honda’s Internavi system was used to facilitate recovery efforts following the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan by pinpointing where roads were damaged based on automobile movement patterns.85

“Thinking about the citizens first is where the government used to be. Today we’re more professional then ever, but people have more faith in governement. People don’t care if it takes two days or two and half days to fix a pothole, they care that it gets done, and they care that they’re heard.”—Nigel Jacob, Co-Founder, Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics, City of Boston

Another opportunity lies in better tracking critical items, as in the case of food safety. By creating simple interaction points along the supply chain with barcode scanners, RFID tags, or QR codes, inspectors could quickly learn the origin of a specific shipment in the case of food-borne sickness or other contamination. When a juice company recently found traces of a particular chemical fungicide, the US Food and Drug Administration halted all shipments of orange juice into the country until it could complete an investigation.87 Location data could provide a much clearer and more accurate way to trace the problem fruit back to the original farm.

Location analytics terminology

- User analytics: Correlating location metadata with an individual’s current activity

- Geofence: A digital boundary for grouping location-based data

- Dwell time: Amount of time a user spends in a particular location

- Social sharing: Amount of social data the user is generating (tweets, posts) in a place

3. Design geo-intelligent programs

The blend of new digital signals and the tools to process them creates opportunities for government to rethink the way it approaches traditional problems. Geo-intelligent programs can create a new framework for collecting data and shaping strategy in a way that saves public dollars and delivers better results.

Test out new services with “geo-pilots.” In 2010, the the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) began rolling out a national map to identify regions of the country with access to broadband. To validate coverage and broadband-speed data collected from Internet providers, the FCC’s then-managing director (now Federal CIO) Steve VanRoekel first considered assigning the task to a contractor but was deterred by the price tag and limited geographic coverage available. A second option, installing sensors on every postal truck, also was shot down because of cost. Instead, the agency came up with the FCC Mobile Broadband Test app for Android and iPhone.88

The result? “We had millions of data points come back to us,” said VanRoekel. “It cost something like $50,000 to build this whole infrastructure in apps. There were questions about the data quality… but what we noticed was that by looking at different points of data and starting to build relationships between the points… you could start to get a really meaningful map put together. As a decision metric, it was pretty powerful. And it was super low cost.”89

Agencies can take advantage of the data collection power of employees or citizens, whether as volunteers or in exchange for some perceived value (such as the broadband app, which showed users their Internet speed). This kind of experimentation can be useful for tracking things such as the effectiveness of healthcare interventions and new field office locations.

Use a blend of active and passive data collection. Many are familiar with 311 apps, which allow users, for instance, to take a picture of a pothole or some graffiti and submit it to the city for repair. But what if you didn’t even have to ask? The Boston Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics is taking advantage of sensor technologies in most new smartphones to passively sense potholes.

The application, called Street Bump, runs in the background while users drive down the road. Data about road conditions are collected via the phone’s accelerometer (the same technology that turns the screen sideways when you tilt the phone). With every bump, signals are captured, geotagged, and uploaded to a database that aggregates the bumps felt by all users. The result is a map of Boston’s bumpy roadways that helps direct public works crews to the worst stretches receiving the most traffic.90 Before the app, work crews drove around in pickup trucks dragging heavy chains to measure vibration, costing the city $200,000 each year. Street Bump, by contrast, was developed with a one-time expense of $80,000—and some battery life from citizens on their way to work.91

New solutions built with location-based data

- Asthmapolis: Through a GPS tracker inserted in asthma inhalers, this app maps and tracks symptoms and potential triggers for attacks, letting users review trends.92

- Avego: This app allows drivers to find people to share rides in their cars, helping to address road congestion while cutting their own costs.93

- Satellite Sentinel: This public-private partnership, made famous with support from George Clooney, uses satellite imagery to draw attention to violence in the Sudanese border region.94

- The “squares”: Of the dozens of apps built using the Foursquare API, two are particularly interesting. BlindSquare helps blind users navigate unfamiliar areas using check-in data.95 Another, FearSquare, alerts UK users of the number and types of crimes committed at or near their most recent check-in.96

- Waze: With 15 million users, this driving app leverages crowdsourced data to provide real-time traffic information.97

4. Use place-based thinking to redefine “public” services

When government sets out to solve big problems, most solutions require an investment in new personnel or new equipment. But what if location data could be used to reduce such expenditures? A combination of place-based thinking and creative problem solving can allow government agencies to tap the resources of the whole community to solve challenges without big investments.

Put public works up for “adoption.” Consider a scenario where members of the public might fight over the chance to do the work of government employees voluntarily. This is exactly what happened with Boston’s Adopt-a-Hydrant program.98 During a Boston winter, piles of snow can make it difficult to navigate the narrow streets of the old city. Enter Erik Michaels-Ober, a fellow with Code for America. The interactive map platform he created allows citizens to “adopt” a hydrant (and even name it!) and volunteer to clear snow from around it, freeing city workers for other tasks.

The city plans to expand this program to other infrastructure, and the local government of Honolulu has copied it with an “adopt a tsunami siren” program.99

Rethink service delivery through disruptive innovation. Many people are familiar with food trucks, but what if government services were no longer tied to brick-and-mortar spaces? Two companies, Hello Health and Sherpaa, are redefining the way individuals engage with healthcare providers.100 Created by Dr. Jay Parkinson, these platforms allow doctors and patients to interact in person and online outside the standard confines of a doctor’s office. And people are signing on to this approach—within the first month, his Hello Health site received 7 million hits.101 Changing the location constraints of health delivery, powered by mobile technology, could equate to big changes for regulators, insurers, and government gencies responsible for ensuring accessibility and quality of health services.

In sectors like health care, location-based technologies are expected to be highly disruptive. Where people used to have to go to the doctor to get tested for the flu, in the near future they may be able to spit on their smartphone for a diagnosis.102 An unsettling thought, perhaps—but how would such technology change the need for doctors’ offices, or alter how government health providers interact with certain populations? Mobile health apps might be a way to engage healthy young people who avoid regular check-ups, or the elderly who struggle to make a trip across town. Thinking about service delivery through the lens of location-based technologies can help agencies make smarter decisions about investments in physical infrastructure.

In some ways, this future has already arrived. For someone suffering from cardiac arrest, minutes can mean the difference between life and death, and emergency medical crews can’t always get there immediately. PulsePoint is a mobile app that connects heart attack-related 911 calls with individuals nearby who are certified in CPR to provide immediate assistance until an ambulance can arrive.103

Problems addressed with new models:

- Improve the citizen experience. Research shows that 74 percent of US smartphone owners use their phones to access location-based information, a number that has doubled in the past year.104 Innovation in commercial location-based services is driving consumer expectations, leading citizens to expect more from government as well. Advances in location analytics can allow government agencies to improve their interactions with the public and harness data to design services more effectively.

- Target government actions more effectively. In some cases, government develops solutions without getting to the root cause, such as the FDA’s temporary ban on all orange imports, which can adversely impact economic or program performance. Collecting signals from multiple sources, including physical assets, can help government better manage program performance and target solutions.

- Use digital exhaust to evaluate performance. Identifying inefficiencies, reviewing performance, and prioritizing spending in large, complex programs can be difficult without costly evaluations.105 By tapping the “citizen sensor network” to collect information about service usage or infrastructure quality, government can aggregate small signals to guide its investments without expensive evaluation efforts.

- Create new, more efficient delivery models to cope with decreasing budgets. Continued advances in mobile device and sensor technology may break the brick-and-mortar constraints that once anchored services such as healthcare and social services to fixed locations. Geospatial collaboration platforms and location-based data can support new models of service delivery that serve citizens where they are, avoiding costly investments in physical infrastructure and engaging the public as partners to achieve better outcomes.

Putting zoom into practice

Employing the principles of zoom may require government to do more than simply add new technology to existing programs. The combination of new data and new problem-solving approaches can impact mission offices, shared services such as technology and human resources and liaisons with external partners including the public, industry, and other agencies. This section outlines how agencies can put zoom into practice through three considerations:

- Collect the location-based data already within the agency, and integrate location intelligence into employee decision making.

- Connect with external partners and data sources that support mission priorities.

- Protect citizens and employees by understanding the privacy issues related to location-based data, and focus on delivering value in exchange for sharing location information.

Collect: Assembling the data within

Breaking down mission priorities according to their “place” components (such as “Where is my agency serving the most citizens, and why that place?” or “Which of my assets are most utilized, and how does that compare to other places?”) can help leaders get a sense of the ways place-based analysis and location intelligence could frame a possible solution.

Look for the geo-data within. Many government agencies already have data with a place component—information that lives in spreadsheets and is infrequently expressed through a geospatial platform. Facilities information such as computer-aided design drawings or architectural specs and administrative data such as official records, patient or constituent files, invoices, and workforce data already possess location metadata such as geographic coordinates and addresses. When combined with traditional GIS data, this information can be used to paint detailed informational portraits.

Don’t wait for perfect data. Governments already possess volumes of rich data and can gain real insights from information already available—even if it’s incomplete. By visualizing data for preliminary analysis to predict, speculate and infer (not conclude), patterns emerge that may lead to more detailed investigation. Consider the “small signals” from mobile phone data in Haiti that are enabling new models of crisis response; tracking the location of several thousand didn’t account for everyone, but it provided responders with an improved understanding of how people might react in future disaster scenarios.

Reduce friction to collect better data. Lastly, it’s important not to overlook employees’ capability to collect more and higher-quality location data. By reducing the amount of “friction” in reporting—that is, making geolocated data entry easier for front line employees—agencies can take advantage of entirely new sources of information. This friction could be reduced in several ways:

- Take mobile tech to the front lines. Employees and citizens equipped with mobile devices and tailored apps can automatically geotag data, including metadata such as pictures, location-tagged notations, and contextual data. Such practices elicit a sense of community and empower employees and citizens—consider the case of Tandale. With a few GPS-enabled phones, residents and World Bank staff were able to geotag places of interest to put Tandale on the map.

- Make data collection geo-automatic. Agencies can create programs that enforce quality control rules. For example, location data such as addresses or zip codes could be verified automatically for consistency against matching databases, to check their accuracy and completeness. ARRA did so and was better able to respond to critics, reduce fraud, and geo-audit recipients.

- Reveal insights to the organization. Geospatial visualizations offer a common frame of reference for diverse parts of an agency. By opening data internally and encouraging employees to engage with geospatial platforms, managers can promote collaboration and the discovery of interesting trends.

Support a geo-capable workforce. Place-based analysis can be a natural integration point between mission and technical offices, but the continued evolution of geospatial technologies will likely require agencies to cultivate cross-functional skillsets among employees. While many agencies have GIS units, integrating location intelligence across the agency could require more individuals with expertise in statistics, computer programming, and data analysis. At the same time, by incentivizing frontline employees and mission experts, not just technologists, to understand the basics of geospatial and mobile technologies, agencies can better take advantage of new capabilities, and interface more effectively with external partners.

Connect: Look beyond program or agency boundaries to enhance location intelligence

To take full advantage of the potential of zoom, agencies can connect information across the ecosystem of data falling within their mission space. This involves looking to data sets from other programs and agencies as well as the private sector. It’s also important to consider how specific agencies can most effectively motivate citizens to contribute useful information.

Engage through existing platforms and partnerships. Federal, state, and local governments oversee an immense amount of both existing and collectable geotagged information. To take advantage of potential partnership opportunities, government agencies should become active participants in and users of geospatial platforms within (like FGDC’s geoplatform.gov) and outside of government. Data platforms are subject to the network effect: The data becomes more valuable as more and more users participate. By contributing, and building to such ecosystems, agencies may see a greater return. University partnerships can harness academic research for real-world solutions, and the government can also find overlapping goals and missions with the private sector. Consider FEMA’s ongoing collaboration with large retailers, like Target and Walmart, to respond more effectively to future crisis scenarios.

Create a geo-following. A number of policy areas are of interest to groups of private citizens, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations which could become partners in collecting and analyzing geotagged information—it’s a matter of finding the right balance of incentives and workload. USAID utilized microtasking to assign small pieces of laborious geocoding work to citizens who were passionate about USAID’s mission, and were willing to share their time and skills to provide better data for the agency. In Boston, the New Urban Mechanics demonstrated two other means of obtaining public participation. With Adopt-a-Hydrant the city tapped into citizens’ pride in their community by taking ownership of a hydrant, whereas with Street Bump the experience was “passive”—beyond downloading the app, little effort was required to receive the benefit of better roads.

“In the long term, a number of issues may arise as citizens collaborate more with government. As we use social media on phones and tablets to report potholes, crimes, leave a note for the town watch group, the boundary between public and private are blurred. There will be concerns about what can be done with it, what can be released and what is appropriate to share with the public.”—Robert Cheetham, Chief Executive Officer, Azavea

Protect: Address the privacy challenges of location-based data

The factors that make location data useful—the ability to visualize individual behaviors and patterns—also create risk with regard to privacy. As the US Court of Appeals wrote in a 2010 opinion on warrantless GPS tracking, “A person who knows all of another’s travels can deduce whether he is a weekly churchgoer, a heavy drinker, a regular at the gym, an unfaithful husband, an outpatient receiving medical treatment, an associate of particular individuals or political groups—and not just one such fact about a person, but all such facts.”107

Moving forward with the rapidly evolving capabilities of location-based services will likely require government to develop adequate and flexible privacy regulations with a focus on educating citizens and consumers about how their data is being used. At the same time, agencies should ensure that the benefit for citizens outweighs the risk of providing location information.

Be transparent about collection. In November 2011, two shopping malls in California and Virginia tracked the Wi-Fi signals of shoppers’ smartphones as they walked through the mall. Without any notification, aside from a few small signs about a “survey,” the technology monitored patterns to see which stores individuals entered and how long they spent in different locations.108 A few days after this information became public, the malls received a call from US Senator Charles Schumer’s office asking the service to be suspended, while calling for the US Federal Trade Commission to examine the legality of the process.109

This example illustrates the challenges that organizations can face by engaging in location analytics without taking the time to adequately inform users about how their information is being collected, analyzed, and stored. In a recent study, Pew found that 57 percent of app users have either uninstalled or declined to install an app because of concerns surrounding sharing their personal information.110 While the White House’s new digital privacy framework and “consumer privacy bill of rights” are helping to shape government’s response to the ongoing challenges of privacy in the digital age, for many agencies, specific rules and structures are already in place to handle personally identifiable information, though these guidelines will need to evolve to account for the unique challenges of location data.111,112

Providing a transparent and secure experience that preserves privacy by design, while clearly defining the value proposition for citizens, will likely become a priority for agencies.

Frame services around value. Consumers are becoming increasingly comfortable sharing personal information—almost three-quarters of US smartphone owners use location-based services, and Facebook executives noted that over 200 million users shared 2 billion location-tagged posts in a single month.113,114 These applications offer users some sort of value in exchange for sharing their social and location data, whether it’s keeping in touch with friends or finding the fastest way to get somewhere. There is an expectation of privacy on the part of consumers (and employees) that has continued to shape and evolve many companies’ policies, but the point is that millions of people are willing to share very personal data if they feel they are receiving a better product or service in return.

For government, efforts ranging from mobile apps to new forms of location analysis should be framed upon a clear economic or policy benefit that is communicated to citizens upfront, and considers privacy protections from the start.

Zooming ahead

Location-based data will change how we interact with our world. The devices that connect us to one other, and the sensors that speak for our natural and manmade environment will paint a portrait of how we engage with each other and the places where we live. When something as simple as a discarded coffee cup can tell a story about relationships that were once invisible, the possibilities to understand ourselves and each other are limitless—as are the possibilities for governments to address our most pressing societal needs. The principles of zoom can enable better policymaking, improved service delivery, and new opportunities to reinvent government programs.

Place plays a significant role in defining who we are. How we shape our communities and connect with one another reflect the values at the foundation of our society.

Zoom helps government get back to basics, empowering public servants and the community to work together to solve our most pressing problems at any scale—within local communities or from a global perspective.