A Tale of Two Capital Markets has been saved

A Tale of Two Capital Markets Critical playbooks for a bifurcated economy

01 January 2012

- Akin Alaga

The split between cash-rich businesses and those in need of capital has set the stage for a bifurcated economy, with growing challenges for small and medium-sized companies. It has become increasingly important for CEOs, CFOs, and Boards to tighten alignment between their business and financial strategies—with very different playbooks for those on different sides of the divide. Factors like economic lethargy in Europe and America, and fast-paced growth in emerging markets present both rare opportunities and daunting risks.

Capital: Ten things every CEO, CFO, and board member should understand

Capital: Ten things every CEO, CFO, and board member should understand

1. The large amount of maturing corporate debt promises to make the availability and cost of capital a key strategic variable

Over the past year, numerous reports have focused on an impending debt maturity wall in the United States as financial and economic experts try to anticipate the next financial crisis.

Perspectives vary on the dangers posed by the debt maturity wall; however, the general fear is that the amount of corporate debt due for maturity over the next few years will exceed the amount of debt typically issued by the markets.

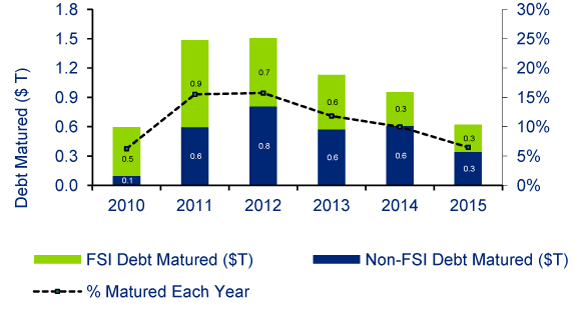

In order to bring a global perspective to the issue, Deloitte* analyzed more than 9,000 public companies in the G20. The graph shows that, at the time of our research, three times the amount of debt that matured in 2010 was expected to mature in 2011.

Overall , the graph illustrates that of nearly $11.5 trillion of corporate debt is scheduled to mature over the next five years—with much of this concentrated in the financial services industry. The emerging debt maturity wall is approximately 61 percent of the total market debt of these companies.

These large amounts of maturing corporate debt promises to intensify competition for capital among companies, making access to and the cost of capital a key strategic variable in most sectors.

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 1. Global debt maturity schedules

2. Corporate debt maturity patterns appear similar worldwide, suggesting that global competition for capital will intensify

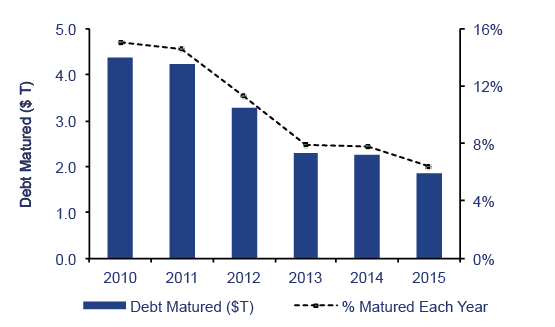

The Americas account for most of the maturing debt—$5.7 trillion of the $11.5 trillion globally. Within the Americas, the financial services industry accounts for $2.8 trillion.

Asia has the lowest debt, but Asian companies have the highest proportion of outstanding debt maturing—69 percent in the next five years.

Similar patterns of increasing debt maturities across the world suggest intensifying global competition for capital.

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 2. Americas debt maturity schedules

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 3. EMEA debt maturity schedules

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 4. Asia Pacific debt maturity schedules

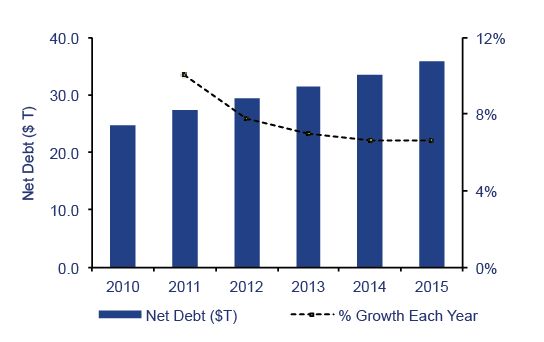

3. Public sector debt will further intensify demand for future capital and likely generate volatility in capital markets

Between 2011 and 2015, the net government debt of the G71 is expected to exceed annual global output. Sovereign debt in the broader G20 is also expected to continue to grow, creating tremendous public sector demand for capital. Fortunately, the amount of sovereign debt refinancing in the G20 is projected to come down steadily for the next five years. Nonetheless, public sector demand for capital will intensify all demand for future capital and likely add to the volatility of capital markets.

The Greek and Irish debt crises have already illustrated how sovereign debt can drive volatility in European and other major financial markets. In addition, various European countries are already confronting political and social unrest as governments undertake austerity measures to rein in deficit spending. In North America, there are concerns over state and municipal defaults that could create new volatility in debt markets. We expect a series of local financial challenges and restructuring to continue contributing to global volatility in financial markets.

Source: Bloomberg and IMF

Figure 5. G7* sovereign debt projections

Source: Bloomberg and IMF

Figure 6. G20 sovereign debt maturity schedules

4. Bank regulations, failures, and collapsed markets for collateralized debt will continue to limit the availability of capital

New banking regulations, such as Dodd-Frank and the Basel 3 Accords, increase the liquidity requirements and reserve ratios of banks, thereby constraining the amount of capital available for lending as a wall of corporate debt matures.

Bank failures further compound constraints on lending, especially in the United States. During the last recession (2001-2002) in the United States, 15 failed banks were taken over by the Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC). In the 2009-2010 downturn, there were 297 bank failures.2 The loss of local and regional banks makes access to debt capital harder for small businesses.

Other sources of debt capital, such as the market for collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), have also collapsed. In 2000, global issuance of CDOs was $68 billion, increasing to more than $455 billion in 2006. In 2010, the total issue of CDOs was barely $8 billion.3

As we get closer to the peak demand for refinancing debt, new regulations and continued bank and market failures will likely limit the availability of debt capital.

Nevertheless—as we will discuss later in this study—the issuance of high-yield debt is one way some companies are still able to access capital at a reasonable cost.

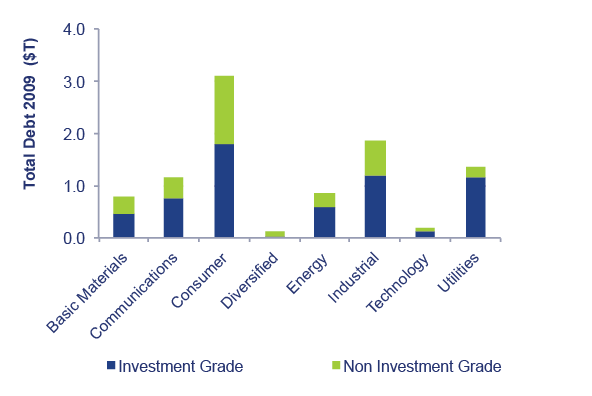

5. Industry matters—most debt outside of financial services is concentrated in the consumer services and industrial sectors

The Financial Services Industry (FSI) accounts for the majority of the $11.5 trillion maturing corporate debt—nearly $5.9 trillion globally. The remaining $5.6 trillion is distributed across a variety of industries; consumer products and services such as retail having an especially high leverage.

Nearly 92 percent of FSI debt is currently rated investment grade. Thus, most non-investment grade debt lies outside the financial industry. Our industry analysis shows that the consumer services industry carries the highest leverage with almost half of its debt being non-investment grade. The bottom line is that some industries will be more challenged than others in managing the large amounts of debt scheduled to mature over the next few years.

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 7. Global debt maturity schedules by industry

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 8. Non-FSI debt grade by industry

6. Size matters more—smaller companies have the highest proportion of non-investment grade debt

Company size also matters. Our research reveals that most non-investment grade debt is generally concentrated among small companies with market capitalization of less than $5 billion, while larger companies’ debt is almost completely investment grade. For the most part, smaller companies tend to have lower credit ratings, and company size is a key variable in credit ratings.

In the next section, we review interest spreads between different grades of debt. However, our company size analysis illustrated in the graph above underscores how any change that increases spreads will likely put smaller companies at a disproportionate competitive disadvantage with regard to cost of capital.

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 9. Non-FSI company size and debt grade analysis

Figure 10. Company size definitions

7. Increasing spreads will likely disproportionately challenge smaller, leveraged companies

After a spike in credit spreads during the financial crisis and then a decline through 2009, credit spreads began to increase again in 2010. Based on our discussions with bankers and analysts, we expect this volatility in spreads to continue as more debt comes due, public sector demand for capital grows, the broader economy rebounds from the recession, and bank regulations and failures further constrain the supply of debt capital.

Indeed, despite a new round of quantitative easing in the United States, rates on treasury securities and mortgages have unexpectedly gone up, suggesting investors anticipate higher interest rates.

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 11. Average spread between AA and BB rated U.S. bonds

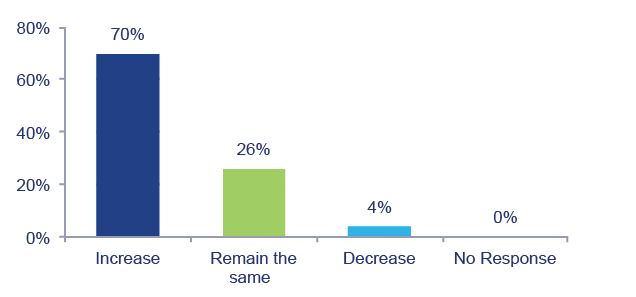

8. Despite the looming debt wall, Deloitte’s CFO surveys find most CFOs optimistic that their capacity to service debt will increase. In contrast, the Duke CFO survey,* which has a sample of smaller companies, says nearly 30 percent of CFOs find it harder to refinance today than a year ago

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 12. Asia Pacific: CFO debt servicing expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 13. EMEA: CFO debt servicing expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 14. Americas: CFO debt servicing expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 15. Global: CFO debt servicing expectations

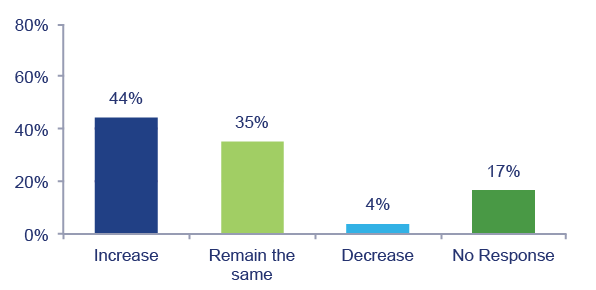

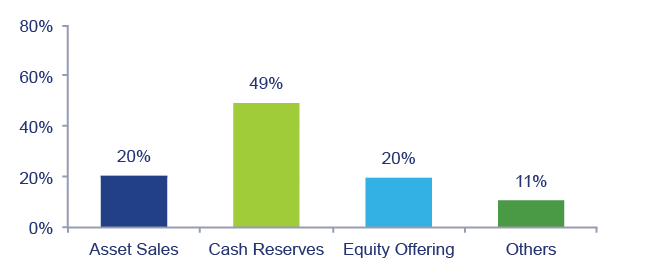

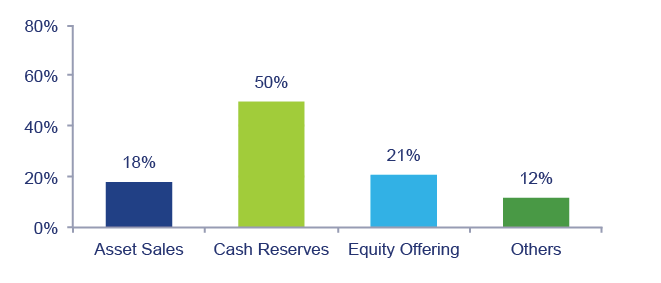

9. Most respondents to Deloitte’s CFO surveys across the world also expect to use cash reserves to pay down debt

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 16. Asia Pacific: CFO’s source of debt payment expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 17. EMEA: CFO’s source of debt payment expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 18. Americas: CFO’s source of debt payment expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 19. Global: CFO’s source of debt payment expectations

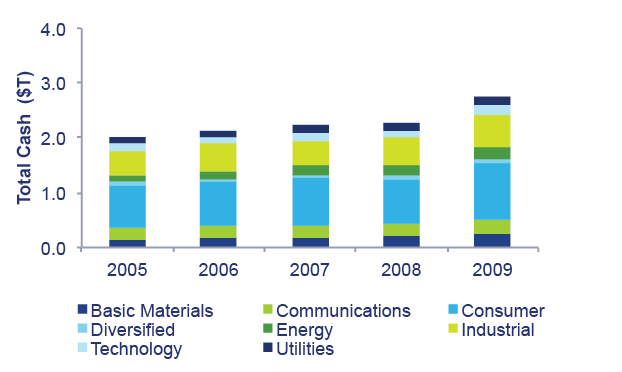

10. Cash is king—in the context of limited capital, cash reserves will increasingly be called upon to drive business strategy

Our research found that prior to the recession, companies in the aggregate were accumulating cash in excess of what they needed to grow.4 This was fortunate, as companies entered the recent recession with unprecedented amounts of cash on their balance sheets, allowing them the flexibility to navigate the worst of the credit crisis. The graphs above show many CFOs have continued accumulating cash over the last two years as they cut costs, conserved earnings, and reduced leverage at a time of uncertainty. This has created more than $9 trillion in cash reserves across the 9,000 largest companies.

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 20. Total cash reserves ($T)

Source: Bloomberg

Figure 21. Non-FSI total cash reserves by industry

These cash reserves are unevenly distributed and mainly reside in the financial services industry, with about $2 trillion of cash outside financial services. Unless this cash is deployed to refinance companies, there is potential for a deficit in refinancing non-FSI debt. Furthermore, many companies have cash in offshore locations. Repatriating the cash—say to the United States—can raise the effective tax rate of the company if not planned properly.

Future retained earnings may further ameliorate the gaps between cash on hand and debt coming due over the next five years. However, we expect shareholders to increasingly demand growth or a return of the corporate cash reserves through dividends or share repurchases. CFOs will need to frame financial strategies to deploy the cash they have been accumulating.

The emerging picture of two capital markets

Our review of the demand and supply of capital for debt financing since the 2008 credit crisis suggests a new context for business—one where access to and the cost of capital are emerging as critical determinants of business strategy and success.

A large amount of debt is coming due over the next five years—more than $11.5 trillion—among the largest 9,000 companies globally. This is unfolding at a time of increasing constraints on capital availability due to increasing public sector debt, bank failures, new banking regulations, and the collapse of key markets for structured financial instruments such as CDOs.

Surprisingly, most CFOs in Deloitte’s global CFO surveys are sanguine about the ability to increase their capacity to service debt. Many plan to turn primarily to the cash reserves their companies built both before and during the recession.

This is a luxury that may be available to mostly larger companies, the focus of Deloitte’s surveys. In contrast, nearly a third of the respondents of surveys on CFOs at smaller companies (such as the Duke CFO Survey) said it was harder to raise financing in the third quarter of 2010 versus the same period of 2009. Thus, our focus on larger companies may underestimate the difficulties of credit access and costs to smaller companies.

The widening gap

- Cash is unevenly distributed across industries, not just among companies within a particular sector. Unless the financial services industry lends or invests its cash in varied industries, companies outside the financial services industry could face potentially severe credit constraints.

- An analysis of non-investment grade debt and changing credit spreads shows that smaller companies are especially vulnerable to increasing spreads and volatility in credit markets. Differences in cost or difficulties in access to capital can be a key source of competitive disadvantage.

- Some say the convergence of growing demand for debt with supply constraints has created a new normal in capital markets. A more accurate descriptor would be two new normals—reflecting dramatic differences between cash-rich and cash-challenged companies. Competition for capital will most likely favor investment grade companies over non-investment grade companies as both seek to refinance debt obligations.

CEOs and CFOs of large companies with solid balance sheets have an opportunity now to access bank loans, debt markets, and equity markets at low costs to finance their growth or boost shareholder value. In contrast, companies that entered the crisis with high leverage and a lot of debt coming due in the next few years have to defend their turf and find ways to improve their balance sheets. Many of these companies will struggle to refinance their debt.

What should CEOs and boards ask of their CFOs?

In the “two new normals,” effectively aligning financial and business strategy is essential for success.

As the marketplace for debt capital changes, management and boards need to ask their CFOs the following four questions:

- What is the amount of debt coming due over the next five years and the vulnerability of the company to different scenarios and volatility in debt markets?

- How will future debt requirements be addressed—refinanced, paid down, or both?

- What are the opportunities that can be seized in a bifurcated economy where cost and access to capital are key differentiators?

- What are the key financial and business strategy playbooks that are available to the company to support shareholder value?

In the new normal, we believe shareholders will increasingly put pressure on management and/or stock prices if financial and business strategies are not fully aligned.

Navigating the bifurcated economy: Choose your playbooks

Capitalization and strategy

Capitalization can be a critical enabler of strategy. In advance of the 2008 credit crisis, a global manufacturer raised substantial capital to support a multi-year global transformation of its products, operations, and processes.

This strategic choice proved remarkably fortunate during the credit crisis. Having set the issue of capital aside by raising it in advance of the credit crisis, the company was able to focus on what mattered—responding to a challenging marketplace by creating more competitive products. In contrast, some key competitors were forced to seek bankruptcy protection and government support for re-organization during the credit crisis.

Capitalization can dramatically impact the broader strategies of a company. Today, this insight grows more salient as capital access and costs become critical to a company’s success.

Choosing your playbooks

Given the bifurcated economy, boards, CEOs, and CFOs need to work together to frame two critical playbooks in the emerging marketplace. Both playbooks need to be aligned.

- The capitalization playbooks frame how the company chooses to provide capital to sustain and grow its operations, or to undertake new investments.

- The strategy playbooks frame how the company will grow going foward or defend its position in the marketplace.

The capitalization playbook: Overview

At any given time, CFOs generally have four ways to capitalize new investments for growth or to sustain operations. These include using:

- Retained earnings

- Debt capital from bank loans or the issue of debt instruments

- Capital raised from the issue of equity and

- A combination of debt and equity financing, as in convertible bond offerings.

The availability of capital from all these sources was severely impaired and altered by the economic crisis—and it has also resumed at different rates for different sources. The emerging debt maturity wall, combined with potential volatility from any future sovereign debt crisis, makes it imperative for CFOs and management to frame an effective capitalization strategy for the next several years.

Our worldwide surveys show the primary way most CFOs intend to address existing debt is by drawing on cash reserves. Given some of the difficulties with debt and equity financing today, this is not surprising. Despite cash reserves, however, many companies will have to rely on debt or equity capital to overcome shortfalls in financing or to enable growth. The choice between the type of debt and equity capital will vary by the types of financial services and markets available by region, and the context of individual companies.

The capitalization playbook: Bank debt

Companies can generally seek bank loans or issue bonds to investors to raise debt. Despite quantitative easing in the United States, and other initiatives in Europe, the annual bank loans in the major North American and European economies are unlikely to reach pre-crisis levels for the next few years as banks continue to de-leverage to improve their balance sheets.

Regulations like Dodd-Frank and Basel 3 decrease leverage ratios and increase the reserve requirements of banks, thereby reducing the amount of capital they may put at risk.

Markets for collateralized loan and debt obligations decreased substantially following the crisis, reducing the amount of capital banks could lend.

Normally, such a contraction in available loans should trigger a major wave of distressed sales and bankruptcies of businesses. But surprisingly, the volume of distressed sales and larger company bankruptcies in the United States has been remarkably low. Many believe that banks are extending and amending loans and pushing them out a few extra years.

While banks may be extending terms on existing loans, many CFOs say the new loans rarely extend beyond three years. While debt covenants have not substantially changed, taking bank debt today often entails greater scrutiny of adherence to covenants.

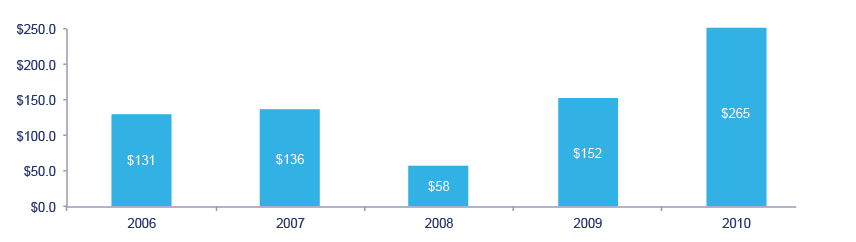

The capitalization playbook: Bond markets

Over the past year, high-yield bond markets have sprung to life, and many companies are able to tap these markets to issue longer-term debt. This is especially true for larger companies with good cash flows and low leverage.

The renewal of high-yield bond markets is primarily ascribed to lack of yields on other assets held by investors, motivating a broad range of investors to seek this class of asset. Terms on bonds are also typically longer than loans offered by banks, permitting greater flexibility for CFOs to stabilize their cash reserves over an extended period of time.

The availability of bond markets in North America and Europe has also allowed some companies to issue convertible bonds. These bonds negotiate a lower interest rate for the bond, but allow buyers to convert the bonds to equity at a premium to the current price. Buyers can capture a potential upside in the value of the equity, while sellers provide capital at lower costs. If the bonds are converted to equity at a premium in the future, existing shareholders are not substantially diluted.

Cash raised from convertible issues can be used to pay down existing higher interest debt, as well as support other shareholder value growth strategies such as share buybacks and mergers and acquisitions. These strategies are discussed later in this report.

Source: KDP Investment Advisors

Figure 22. U.S. issue of high yield bonds ($B)

The capitalization playbook: Equity

While equity indexes in emerging markets (such as India) are nearing pre-credit-crisis peaks, the major European and North American indexes remained close to 20 percent off their peak values at the end of 2010. Thus, for many companies in the largest economies, new equity issues would be dilutive to existing shareholders. Nevertheless, a number of companies have issued new equity to raise capital, especially in financial services where banks needed to shore up their balance sheets. Indeed, many major banks also turned to sovereign wealth funds to help them recapitalize. As sovereign wealth funds begin to support the strategic objectives of their governments, as well as seek higher returns, they are expanding their capacity to directly invest in companies.

New equity offerings can occur through public offerings or private placements. Research shows that in the last quarter of 2010 the Private Investments In Public Equities (PIPEs) market was at its most active in the last two years5 as a means of raising capital—especially by companies with lower access to bank loans or debt markets. Inviting private equity or hedge fund investment into a company often brings a much more active shareholder, with commensurate demands for operating and strategic information.

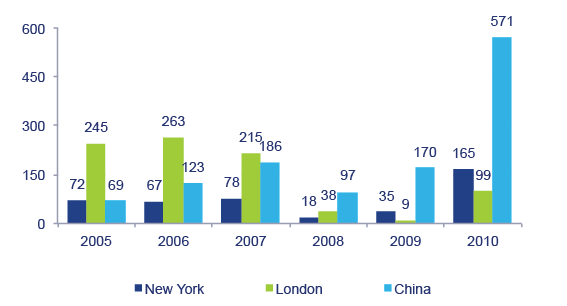

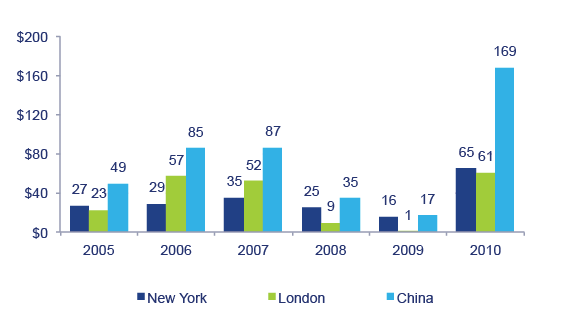

New issues of public equity have also expanded considerably in 2010. The largest volume of new issues were in the Chinese markets of Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong, raising $169 billion in capital. This resurgence is encouraging—and is enabling companies to return to equity markets for capital.

Source: Thomson One Banker - Deals

Figure 23. Number of new equity issues

Source: Thomson One Banker - Deals

Figure 24. Value of new equity issues ($B)

The capitalization playbook: What should CFOs consider?

As illustrated by the collapse of the CDO markets, the resurgence of high-yield debt issues, and the volatility in equity markets, capital markets have taken unexpected turns in the last few years. With substantial amounts of corporate debt coming due, demand for sovereign debt increasing, and other potential surprises, it is important for CFOs to be prepared for the unexpected. Diversifying their sources of capital and getting commitments to fund emerging cash requirements immediately are smart options to consider.

Regulatory pressures and deleveraging make it unlikely that bank lending will significantly increase. CFOs will have to choose between tapping their existing cash reserves, issuing high-yield debt, or tapping equity markets. Public company CFOs may also have to seek capital from alternative sources, such as private equity firms, sovereign wealth funds, and hedge funds.

We are already seeing the increased use of PIPEs by companies as a source of capital. For now, given the generally low interest rates, high-yield bond issues are favored in North America and Europe—although markets for high-yield bonds have been historically volatile. Many analysts expect interest rates to increase in the next few years.

Deloitte member firms’ debt advisory practices find that the time required to raise cash has increased significantly in the wake of the credit crisis. CFOs should generally expect it to take nearly double the time to raise cash. With the likelihood of interest rates increasing, moving forward on a capitalization strategy is imperative.

CFOs must be prepared for change. They will need to continuously test their sources of capital and the commitments they have received. For example, it is important to frequently test bank relationships to ensure they are committed to providing the capital they have promised.

In short, CFOs should consider raising cash now—before it becomes more costly or less available as debt funding. If they foresee substantial debt coming due, or other demands for cash in the next few years, raising capital today takes the issue of money off the table tomorrow—and allows management to focus on executing other elements of their growth strategy.

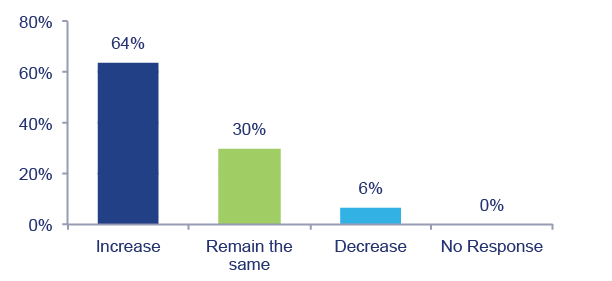

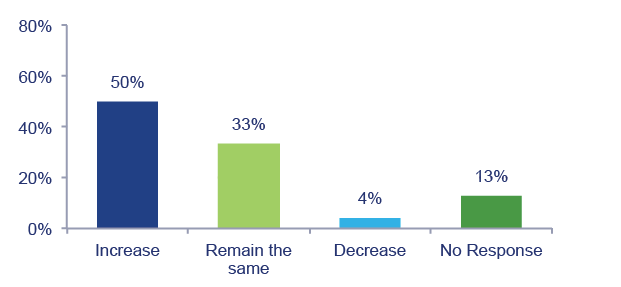

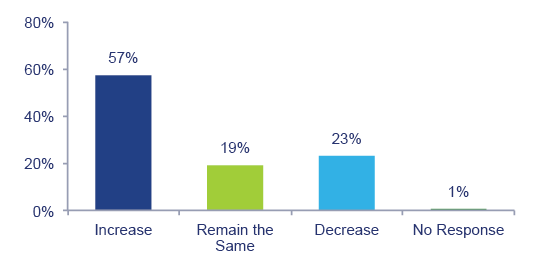

The capitalization playbook: What do CFOs expect about their debt levels?

Despite the impending debt maturity wall, the majority of larger company CFOs surveyed by Deloitte expect to increase their debt levels over the next three years. This is especially the case in Asia and Europe. Expectations of increasing debt suggest further demand for debt capital, which should drive an increase in costs for debt. However, the Americas differ from other regions. The number of respondents who will increase debt almost matches that of those who will decrease it. This affirms a bifurcation of the markets. Some companies will further lever up, taking advantage of current interest rates to fund growth. Others will have to de- leverage to reduce debt burdens.

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 25. Asia Pacific: CFO debt level expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 26. EMEA: CFO debt level expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 27. Americas: CFO debt level expectations

Source: 3Q 2010 DTTL Member Firm CFO Surveys

Figure 28. Global: CFO debt level expectations

Strategy playbook: Overview

Strategy in the “two new normals” differs considerably for companies with strong balance sheets and cash flows versus companies with high leverage and cash flows that have been negatively impacted by the post-credit-crisis downturn.

Given over $9 trillion in cash across major companies worldwide, there is a considerable amount of capital available to target companies for growth. But with the contraction in demand in North America and Europe, companies must consider varied strategies for how they use their cash to increase shareholder value.

The primary strategy playbooks for value creation by cash-rich companies today include equity buybacks, establishing or raising of dividends, investment in high-growth markets or products, and seeking growth through mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

Strategy playbook: For cash-rich companies

CFOs in cash-rich companies face a dilemma: Do they return the cash to shareholders? Do they retain the cash earnings to finance new investments? Or do they do both?

Option A: Two ways to return cash to shareholders

Share buybacks. Share buybacks reduce the number of outstanding shares and the pool of shares to which future earnings are distributed. This can increase value for the remaining shareholders, but can also encourage investors to cash out—including those the company may like to retain.

Dividends. Dividends return cash to all shareholders who own the stock in a fairly equal way. However, dividends are sometimes less tax-efficient, if they are taxed at higher rates than capital gains. Furthermore, this approach may lock in market expectations for continued dividends, even if management wants the flexibility to later use cash for strategic purposes. For some, dividends signal a shift from a growth company to a lower-growth company with stable cash flows.

Of the two methods, buying back shares ultimately gives greater choice to investors as to whether they want to stay in a stock or leave. In contrast, dividends reflect a management choice over how cash is returned—sometimes in a tax-inefficient manner.

Option B: Three ways to retain cash for growth

Mergers and acquisitions. Over 2010, the number and value of M&A transactions grew steadily—and should continue to do so as cash-rich companies seek growth and cash-challenged ones divest assets. Valuations at the end of 2010 were about 20 percent below their peak values in North America and Europe, offering potential bargains for acquirers. In addition, emerging markets should not be overlooked for M&A opportunities, as major indices in Brazil, Russia, India, and China are also off their peak levels and at the same time present the upside for growth in these key markets.

Hostile takeovers. Some cash-rich companies will likely take over cash-challenged companies and change corporate control without even having to purchase equity in the target. Instead, the acquirer will purchase select corporate bonds or fulcrum securities that the target may be unable to refinance in time Control of these bonds are senior to equity and can result in a transfer of control.

Organic growth. As companies adjust to the recession and changing consumer demands in North America and Europe, they are looking to emerging markets for growth. But tapping this growth is not easy, especially as multinationals struggle to find the requisite talent—including finance talent—to help them expand in these markets. New product introductions as an avenue for growth remain uncertain as consumers replenish products less frequently.

Cash-rich companies will have considerable choice among these alternatives to grow shareholder value. Indeed some may even raise debt at current low rates to undertake share buybacks to boost equity values. Boards, CEOs, and CFOs will have to consider the risks and trade-offs of these strategies to their companies.

Strategy playbook: For cash-challenged companies

In contrast to the cash-rich, companies with low reserves, high leverage, and significant debt coming due in the next five years have fewer strategy options for growth. The first imperative is to build cash reserves and de-leverage in order to ride out the forthcoming wave of debt refinancing. Companies should shore up their balance sheets quickly—before the competition for scarce capital creates further competitive disadvantages.

Options for getting more capital

Extend and amend. Seek approvals from banks to extend the current terms of loans five or more years beyond the current market-wave of refinancing. This may be feasible when collateralized by real assets whose value may recover in the five- to seven-year period.

Tap high-yield markets. High-yield markets may permit some cash-challenged companies to refinance existing loans to bonds. This means longer-term maturities on more favorable terms than are available through bank debt. This can help a company steer clear of peak periods for refinancing debt.

Consider raising equity capital. While this may be dilutive to shareholders, it can be used to defer risks from not meeting debt repayments in time. With the combination of cost controls and a recovering economy, share prices have improved, reducing the dilutive effects of new issues.

In addition to trying to refinance debt coming due in the next few years, cash-challenged companies should consider other options for reducing debt.

Options for reducing debt

Divesting assets or equity carve-outs. Increases in valuations since the low point of March 2009 are also encouraging more companies to put assets up for sale. Companies with high leverage should consider what assets they may want to sell to manage through the emerging debt wall and become a prepared seller. Becoming a prepared seller entails sell-side due diligence, with a clear roadmap for separating the sold asset from the parent company. Prepared sellers can gain a significant price premium.

Cost control. Many CFOs look to cost control and savings as a way to preserve cash. For highly leveraged companies, however, this is unlikely to enable enough cash savings to substantially reduce leverage. Still, a sustained focus on cost control is a tablestakes requirement for all leveraged companies.

Cash-challenged companies are substantially constrained from a growth perspective today. Their focus has to be on de-leveraging or refinancing on favorable terms, while boosting shareholder value through tight cost controls or divestitures.

These companies may be vulnerable to hostile takeovers in the next few years. Many will have to divest assets and refocus on a subset of their businesses. Some may have to file for bankruptcy or re-organization. With interest rates likely to increase over the rest of the year, it is imperative that companies consider what actions they should take now.

What should CFOs ask of CEOs and boards?

As access to and the cost of capital become strategic differentiators, CFOs need to engage management and boards on how to use finance as a source of competitive advantage. They also need to address the risks to their strategy that come from a bifurcated capital market.

Specifically, they need to ask management and boards the following questions:

- If cash-rich: What combination of strategy playbooks will the company use to support shareholder value—sharebuyback, dividends, M&A, or organic growth?

- If cash-challenged: What strategy playbooks will serve the company and its shareholders most effectively—extend debt, issue new debt or equity, accept PIPEs, prepare for carve outs, or enterprise cost reduction?

- How will the bifurcated capital market affect the company’s ecosystem and value chain? Are important suppliers or customers facing significant financial risks that could threaten critical supplies or revenues? Do any of your suppliers need to be financed or bought out?

- Who’s responsible for monitoring these ecosystem risks?

- What specific processes do you need to establish in order to ensure that growth strategy and finance strategy are tightly aligned?

- What permissions does the CFO have to raise capital through different means?

Call to action

A new conversation between boards, CEOs, and CFOs

The credit crisis of 2008 and the volatile post-crisis environment create “a tale of two capital markets” for businesses today. It is an environment where economic recovery is constrained in developed economies—and where more than $11 trillion of corporate debt will come due globally over the next five years—all made more challenging by public sector deficits that create significant new competition and add to volatility in capital markets.

Companies with strong cash flows and low leverage have many strategic options to increase shareholder value through a combination of acquisitions, share repurchases and dividends, and organic growth.

Companies with high leverage will have to further diversify their sources of capital and may have to sell assets. These companies may become more vulnerable to hostile takeovers.

In this environment, cost and access to capital are critical drivers of strategy. This demands a new conversation between boards, CEOs, and CFOs. Boards have to ask how capital markets and the emerging wave of debt refinancing impact strategy. CEOs and CFOs have to work together to ensure business and financial strategies are well-aligned and mutually supportive.

For companies with significant leverage, CFOs need to consider moving with urgency to convince boards and CEOs to recapitalize sooner rather than later. CFOs of large cash-rich companies should also move with similar urgency to frame strategies that leverage the strength of the company to raise capital. This move can create a significant opportunity for large companies with low leverage to outdistance smaller competitors.