Zoom out/zoom in An alternative approach to strategy in a world that defies prediction

16 May 2018

How can companies direct attention toward initiatives that have the most impact—and ensure that they’re properly funded? Using two parallel time horizons—one that’s six to 12 months out and another that’s 10 to 20 years—can help boost immediate strategic impact and prepare for the long term.

Introduction: Achieving impact that matters today

With change and performance pressure only accelerating, it may be time to reassess how we approach strategy. Traditional approaches don’t account for the increasing pace of change and risk generating diminishing returns or missing the mark entirely. Fortunately, there is a more promising way to address the challenges ahead.

What’s wrong with the five-year plan?

Despite the challenges of strategic planning in a rapidly changing world, most companies have remained loyal to the five-year plan as a basic framework. Some have moved to a three-year planning horizon to address the growing uncertainty, with a few taking the dramatic step of abandoning a long-term strategic plan altogether.

Learn more

Subscribe to recieve updates from the Center for the Edge

This article is featured in Deloitte Review, issue 23

Create a custom PDF or download the issue

Regardless of the time frame, executives have increasingly adopted a reactive approach to strategy. The goal: to sense and respond as quickly as possible to events as they happen. Many see strategies of movement as the most effective way to cope with change and uncertainty; flexibility and speed are keys to success.

What’s been the result? Many companies are spreading themselves ever more thinly to deal with an ever-expanding array of initiatives. Even the very largest companies are wrestling with the realization that the number of new programs exceeds the available resources. They are also realizing that these initiatives tend to be incremental in nature, due not only to limited resources but to the programs responding to short-term events.

The results are not encouraging. We have been tracking the performance of all US public companies over the last half century. Measured in terms of return on assets, performance on average for all public companies has declined by over 75 percent since 1965.1 If the goal of strategy is to at least maintain current financial performance over time, this is unfortunate evidence that the current approaches are not working.

An alternative approach

Fortunately, there is an alternative to reactive strategy and incremental steps. It’s based on an approach that some of the most successful digital technology companies have pursued over the past several decades. It goes by different names; we call it zoom out/zoom in.

This approach focuses on two very different time horizons in parallel and iterates between them. One is 10 to 20 years: the zoom-out horizon. The other is six to 12 months: the zoom-in horizon.

Key questions across two time horizons

Zoom out

- What will our relevant market or industry look like 10 to 20 years from now?

- What kind of company will we need to be 10 to 20 years from now to be successful in that market or industry?

Zoom in

- What are the two or three initiatives that we could pursue in the next six to 12 months that would have the greatest impact in accelerating our movement toward that longer-term destination?

- Do these two or three initiatives have a critical mass of resources to ensure high impact?

- What are the metrics that we could use at the end of six to 12 months to best determine whether we achieved the impact we intended?

Notice a key difference from the conventional approach—the five-year strategic plan—that many traditional companies take. Companies pursuing a zoom out/zoom in approach spend almost no time looking at the one-to-five-year horizon. Their belief is that if they get the 10–20-year horizon and the six-to-12-month horizon right, everything else will take care of itself.

A desire to learn faster is what drives this approach to strategy: These companies’ leadership teams are constantly reflecting on what they have learned about both time horizons and refining their approaches to achieve more impact in a less predictable world.

Notice, too, that this approach is distinct from scenario planning or scenario development. Many large companies’ top teams have engaged in exercises asking them to imagine a range of alternative futures and focusing on those that seem most likely to materialize. But then the offsite meeting ends, everyone goes back to her day job, and often nothing really changes. However provocative, the exercise is more or less theoretical, with no clear path to taking action to prepare for that future.

In the zoom out/zoom in approach, the meeting is not over until the leadership has aligned around the two or three highest-impact initiatives that can be pursued in the next six to 12 months—and has ensured that these have appropriate resource commitments. What was a theoretical exercise becomes very real, with clear implications for what the company will be doing differently in the short term to build the critical capabilities for the long term.

Beyond the short term

This alternative approach to strategy can have a number of benefits. It pulls executives out of short-term thinking that is driven by pressure for quarterly performance—and forces people out of their comfort zone. Consider: If we focus on a five-year horizon, it’s possible to convince ourselves that our company, and the business environment, will look then pretty much like they do today. But if we really understand the implications of exponential change and shift our focus to 10 to 20 years, it is difficult to envision an unchanged future. Zoom-out challenges us to consider how different our companies could be, and will need to be, to thrive in rapidly changing markets. It prompts us to question our most basic assumptions about what business we really should be in and fights the tendency toward incrementalism that short-term views promote. And it may reduce the risk that we will be blindsided by something that appears trivial today but could end up fundamentally redefining our market.

This approach also powerfully combats the tendency to spread ourselves too thinly across too many initiatives. It forces us to focus in the short term on the initiatives that will have the greatest impact in accelerating our movement toward a future opportunity—and to ensure that those initiatives are adequately funded.

Changing approaches

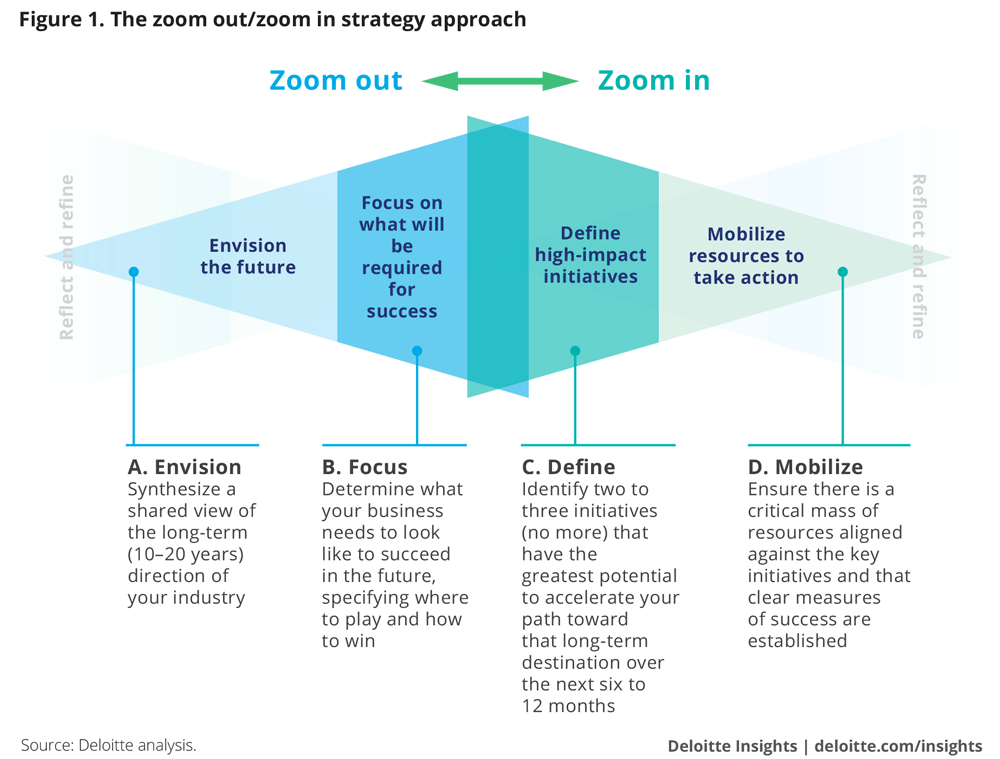

This approach requires us to both expand horizons and narrow focus. While the approach will vary depending on the company’s specific context, figure 1 provides a high-level overview of the approach.

Zoom out. Typically, the first step is to expand the leadership team’s horizons. In part, this involves building greater awareness of the accelerating pace of change, largely shaped by exponential advances in the performance of digital technology. While every executive is at least somewhat aware of these advances, taking people out of the comfort of their corner offices to embark on a “learning journey” to a center of technology innovation—places such as Silicon Valley, Tel Aviv, and Shenzhen—often helps them more viscerally experience what is already occurring and see tangible examples of the accelerating change.

The next step is to start building alignment within the leadership team around a shared view of the 10-to-20-year future. In this context, scenario-planning techniques certainly have a role to play. It is helpful to begin by imagining alternative futures shaped by the key uncertainties ahead. A key to success on this front is to bring in outside provocateurs who can help challenge executives on key assumptions about what business they will need to be in 10–20 years from now.

Here, it’s important to drive an outside-in perspective and to resist the tendency to look at the future from the inside out. Start with the likely evolution of customers and stakeholders. Understand their evolving unmet needs, and then work backward to identify the opportunities to create significant value by addressing those needs in a distinctive way. In addition, focus on leverage: Strive to identify and understand the potential ecosystems that can leverage the company’s capabilities and deliver value to the market.

While imagining alternative futures is helpful, this strategic approach hinges on building alignment around a shared view of what the most likely future will be. This shared view isn’t a detailed blueprint of the future, but it needs to have enough clarity on key trends/opportunities to help executives make choices regarding short-term priorities. Note that it is important to not view the future as a given beyond one’s ability to influence. We have written elsewhere about the opportunity to shape strategies that can materially alter certain futures’ probability.2

As the shared view of the future takes shape, the focus shifts to the implications for the business. What kind of business can create the most value and occupy a privileged position in that evolving future? Here tools such as the “strategic choice cascade” can play an important role, but questions like where to play? and how to play? are framed in the context of the anticipated zoom-out future. The goal is to gain alignment within the leadership team on what the company will need to look like 10–20 years from now to capture the most value and reduce vulnerability to competitors.

Zoom in. This is often the most difficult part: identifying and agreeing on the few near-term initiatives that can most help to accelerate the organization toward the future position. While the specific initiatives will clearly differ based on the company’s context, our suggestion is that for large, traditional companies, the three zoom-in initiatives ideally cover these three fronts:

- Identify and begin to scale the “edge” of the company that could drive the transformation required to become the zoom-out business3

- Determine the one near-term initiative that would have the greatest ability to strengthen the business’s existing core—after all, the core is generating the near-term profits required to accelerate the journey

- Determine what marginally performing activities the company could stop doing in the next six to 12 months that would free up the most resources to fund initiatives on the other two fronts

In developing the zoom-in initiatives, here are some things to watch out for:

- Clustering many initiatives into one “umbrella” initiative—instead, be rigorous about focusing on impact and singling out the one near-term initiative with the greatest potential to deliver that impact

- Favoring the incremental—because the focus is on results in six to 12 months, there is a temptation to fall back to initiatives that are more modest in scope. Even if the chosen zoom-in initiative may take longer to deliver its full impact, the key is to identify a meaningful milestone within this shorter time frame to demonstrate progress. For example, in bringing a major new technology to market, the zoom-in initiative might be the development of a functioning prototype.

Reflect and refine. This is all part of an initial effort to clarify and build alignment around the zoom-out perspective and the zoom-in initiatives. But that’s just the beginning.

The leadership of companies pursuing this strategic approach regularly step back to reflect on what they have learned, both in terms of monitoring the outside world and, more importantly, about the zoom-in initiatives they are pursuing. They typically hold regular sessions to evolve their zoom out/zoom in approach every six to 12 months, driven by the opportunity to assess the results of the zoom-in initiatives. But many of the leadership meetings throughout the year include discussions of both the zoom-out and zoom-in horizons to test and refine the approach on an ongoing basis.

This strategy approach can be a powerful vehicle for learning about the future and how to get there. Such learning requires ongoing reflection and refinement, however, and the pressures of the immediate can make it easier to avoid making that effort. Resist the temptation.

Potential objections to this approach

There’s a natural skepticism that materializes in any effort to expand executives’ horizons. Some of the most common objections:

“The future’s too uncertain.” While we certainly don’t want to be interpreted as saying that anticipating the future is easy, we suggest that looking ahead is becoming increasingly essential. If we lack a clear sense of direction, we risk being consumed by the accelerating pace of change. A key is to focus on reasonably predictable factors such as certain technological and demographic trends.

“Our investors just want short-term results—don’t distract me with the future.” Here’s the paradox: Investors may focus on quarterly earnings, but anticipation of future earnings—that is, the multiple of today’s earnings—drives most of any large company’s stock price. The more a company can be persuasive about significant future opportunities and demonstrate tangible short-term progress toward addressing those opportunities, the better the stock price is likely to perform.

“Any near-term economic impact of this approach to strategy is likely to be marginal; the payback will take too long.” While a view of the future drives strategy, that view can be helpful in achieving greater short-term focus that is likely to improve economic performance. If we have a clearer view of what the future might look like, we are better positioned to take steps that will reduce our vulnerability to near-term disruptions—and to make difficult choices about shedding portions of our business that are currently underperforming. Done right, this approach to strategy has the potential to significantly improve near-term economic performance.

The opportunity ahead

Zoom out/zoom in is a great example of combining and amplifying two competing goals: preparing for the future and achieving greater near-term impact. By focusing on these two in tandem, we have greater potential to accelerate our movement toward the most promising future opportunities and delivering near-term impact that matters to stakeholders. Maybe strategy is less about position or movement than about trajectory: having a sense of destination and committing to accelerating movement to reach that destination.

This approach can be used for an entire corporation; for diversified companies, it can also be applied at the business-unit level.

But it’s not just for companies. Every institution—and every individual—can use this approach to increase impact. What’s our zoom-out opportunity? And what should be our most important zoom-in priorities? Until we can answer those questions, we are at risk of getting buffeted about by an increasingly demanding world and experience more and more stress as we spread ourselves too thinly.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.