Dynamic strategy implementation has been saved

Dynamic strategy implementation

04 December 2013

- Amelia Dunlop, Vincent Firth, Robert Lurie

A dynamic approach to implementation can help leaders sidestep insidious failures in execution that can doom even the most well-thought-out strategy.

Executive summary

Studies consistently show that many strategies fail in the implementation phase. The root of the problem may be traced to three factors: a failure of translation, a failure of adaptation, and a failure to sustain change over the long term. A dynamic approach to strategy implementation can help overcome the limitations of the traditional administrative approach that serves as a breeding ground for these failures. In this article, the authors discuss the key elements of this dynamic approach and how it has helped leading enterprises deliver more effectively on their strategic ambition.

Fighting the inside failures

Every year, top executives in organizations around the world convene their sharpest thinkers to develop strategies to enter new markets, capture greater market share, become more profitable, or otherwise improve some aspect of the business. And every year, a large percentage of these strategies are doomed from the day they are announced. The past is littered with new strategies that were unveiled with much fanfare, only to fall far short of meeting expectations.

The impact of strategic failure varies. The most spectacular cases—when an organization bets the business on a new strategy, misses badly, and ultimately ceases to exist—are the ones that make the news. But these are the exception rather than the rule. Much more common are instances in which a company wants to improve its business but simply does not get the results it seeks. These insidious failures may not turn into attention-grabbing headlines, but they nonetheless negatively affect companies’ performance and could prevent them from capitalizing on growth opportunities.

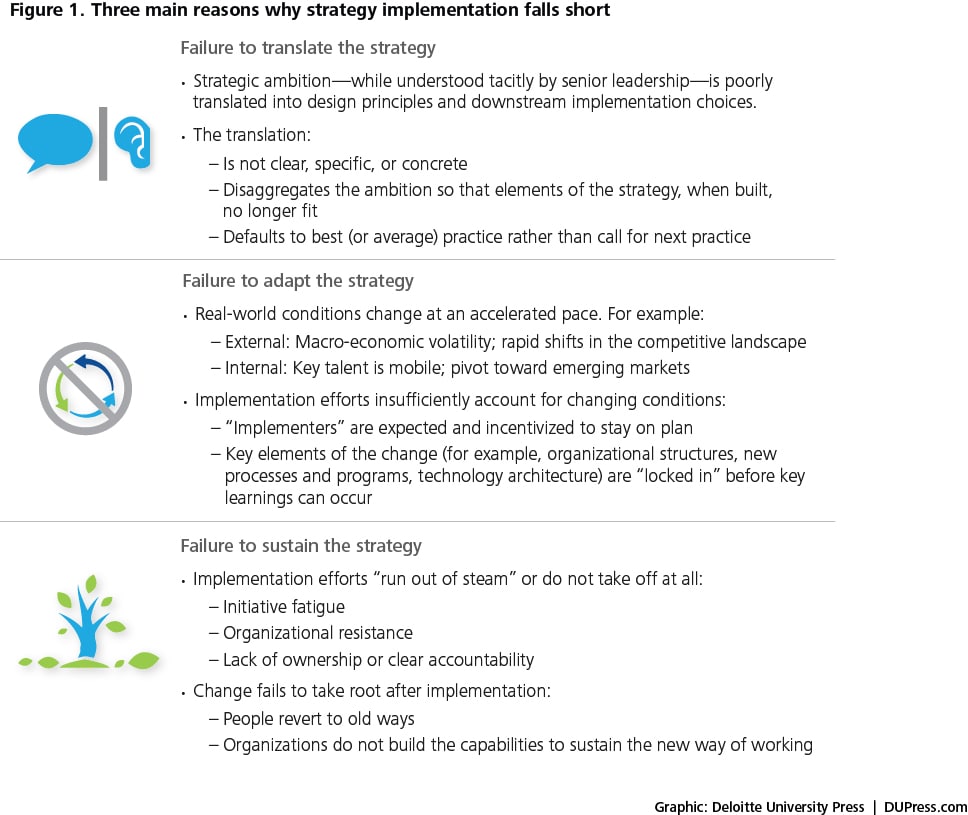

How do organizations go wrong? Often, there’s nothing inherently defective with the strategies themselves. Rather, the strategies do not live up to their promise because the organizations involved don’t do what it takes to effectively put the strategy into practice. More specifically, there is a mismatch between what the strategy was designed to accomplish and the approach taken to implement the strategy. For most companies, the root cause of ineffective implementation can be found in three areas (figure 1):

- Failure to adequately translate the strategy from the CEO’s high-level ambition to specific actions the organization must take to make that ambition a reality

- Failure to appropriately adapt the strategy when conditions change

- Failure to put in place the organizational capabilities required to sustain the strategy after it is enacted

Failure to translate the strategy. The decision to make a significant change in strategy is often not made lightly; it is the result of much thought, discussion, and analysis by a firm’s leaders. The communication of the new direction, however, is often made as terse and aspirational as possible: A series of four to five statements about strategic intent or direction—for example, “be customer-centric” or “accelerate innovation”—are announced to employees and investors alike. The high level and abstractness of these statements are often justified by the rationale that “to implement we have to keep what we say very simple.”

Unfortunately, implementation of the strategy begins to fail right then — before the teams are formed or the detailed plans are laid out. Why? This occurs because too much of the meaning of each strategic intention is left tacit or unclear, and because each strategic intention is presented and then acted upon as if it could be accomplished on a stand-alone basis. Without an explicit picture of what the strategic aspiration means and how the various components fit together, two undesirable things typically happen. First, implementation teams will build what they already know or can glean easily through benchmarking, and may act as if what they are building is consistent with the aspiration. That causes the company to fall short of its strategic aspiration because a new strategy typically requires an organization to do at least some things very differently from how they arcurrently done. Second, implementation teams that don’t know how the parts of the strategy are meant to work together will simply build another silo to meet their own needs at the cost of accurate and integrated outputs.

Failure to adapt the strategy. In many large-scale implementation efforts, companies pay close attention to sequencing key activities and identifying critical dependencies. In doing so, they assume the organization can implement the necessary changes rapidly before conditions change. That assumption flies in the face of reality: Key employees leave, competitors act, customer expectations evolve, and new regulatory laws are passed. In the real world, an organization must respond to a constantly shifting landscape so that moving from point A to point B is rarely done in a straight line, but rather via a series of choices and course corrections in response to internal and external conditions.

Failure to sustain the strategy. One of the major risks inherent in any large change effort (including strategy implementation) is the inevitable slump that occurs as leaders’ initial enthusiasm encounters the headwinds of organizational resistance. Such resistance can arise from sheer fatigue: Individuals tire of waiting for the promised “big bang” payoff after months of up-front investment, and they question the value of the changes being pushed through the organization. Organizational resistance also arises when individuals lack the skill or knowledge to do what’s required of them under the new strategy, and they receive insufficient support to build the necessary competencies. When leadership underinvests in building organizational capabilities, implemented changes fail to take root as individuals revert to old behaviors and approaches.

Dynamic circumstances require a dynamic approach

Failures in translating, adapting, and sustaining a strategy may thwart an organization’s efforts to effectively bring its strategy to life. Even worse, in most cases these failures are virtually inevitable because they are the natural outcomes of the traditional approach to strategy implementation many enterprises use today.

The typical approach to implementing strategy is highly administrative in nature, focusing on the time, manpower, and sequence of activities necessary to enact change. This approach frames the implementation challenge as a giant manufacturing problem: Mechanically break down the problem into pieces, develop a master plan that details the assembly instructions, specify the timing and sequencing of different workstreams, and deploy teams in parallel to assemble the required components according to the specified instructions. The plan might be incredibly complex and layered, but in its essence, it likens implementation to assembling IKEA furniture, only at a much greater scale.

This administrative project management approach is attractive on many levels. It could help ensure that the organization is mobilized quickly. It offers the certainty of clear timelines and milestones, and could provide reassurance that a large and complex issue can be divided and conquered. It provides certainty and clarity on roles and responsibilities, and frees up leaders’ time as they delegate downstream implementation choices to the program management office or individual line and function leaders.

However, the administrative approach is most effective in very specific contexts, such as situations when the organization desires only a modest amount and scope of change, when the competition is stable, or when a top-down, command-and-control approach is sufficient because the organization does not need to learn. Such situations are rare today. Firms frequently face circumstances where the competitive environment changes rapidly, resulting in significant uncertainty and a greater need for the organization to learn as it goes. They also may have strategic ambitions that are broad in scope, spanning a large number of activities, business units, and geographies. Or they may be pursuing an ambitious strategy that requires significantly new capabilities. Thus, because the administrative approach is based on fragmenting tasks and creating highly regimented, largely inflexible project plans, companies that use it generally can’t avoid experiencing one or more of the failures that undermine strategy implementation.

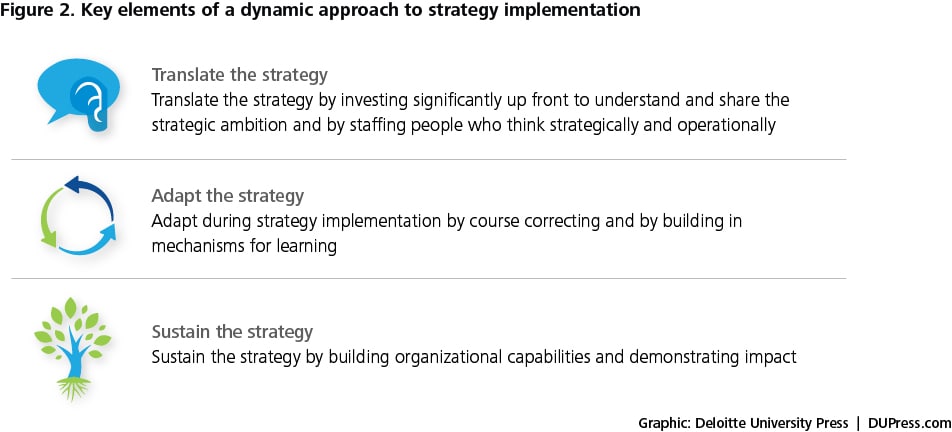

There is, however, an alternative to the traditional administrative approach to strategy implementation. This new, more dynamic approach is based on the belief that—for strategy implementation to be effective—companies must treat it as a leadership activity and avoid structuring or delegating it as a purely administrative activity. Dynamic strategy implementation focuses on translating leaders’ strategic ambition into downstream implementation choices needed to create the desired strategic outcomes, explicitly designing activities to enable the organization to adapt to changing conditions, and investing in capability-building efforts to embed new skills and behaviors deep in the organization (figure 2).

Translate strategy into explicit implementation guidelines and choices. A translation problem arises because strategic ambitions are tacit knowledge (“I know it when I see it”) and require some effort to be made explicit (“I can describe to you what it looks like”). If leaders can’t make their ambition explicit, the rest of the organization will likely find itself forced to interpret the ambition’s meaning on their own.

For example, what should the leader of the customer-centricity team do with a strategic ambition to “become more customer-centric”? Does that mean the company should organize by customer group? Should the team conduct deep research to understand what customers really want? Should the company incentivize its service people to be highly responsive? Should the organization initiate an effort to make its products the highest possible quality in the industry? Should it do all of the above? None of the above? Something else? In this situation, all are possible—and that is the sign of a major translation problem.

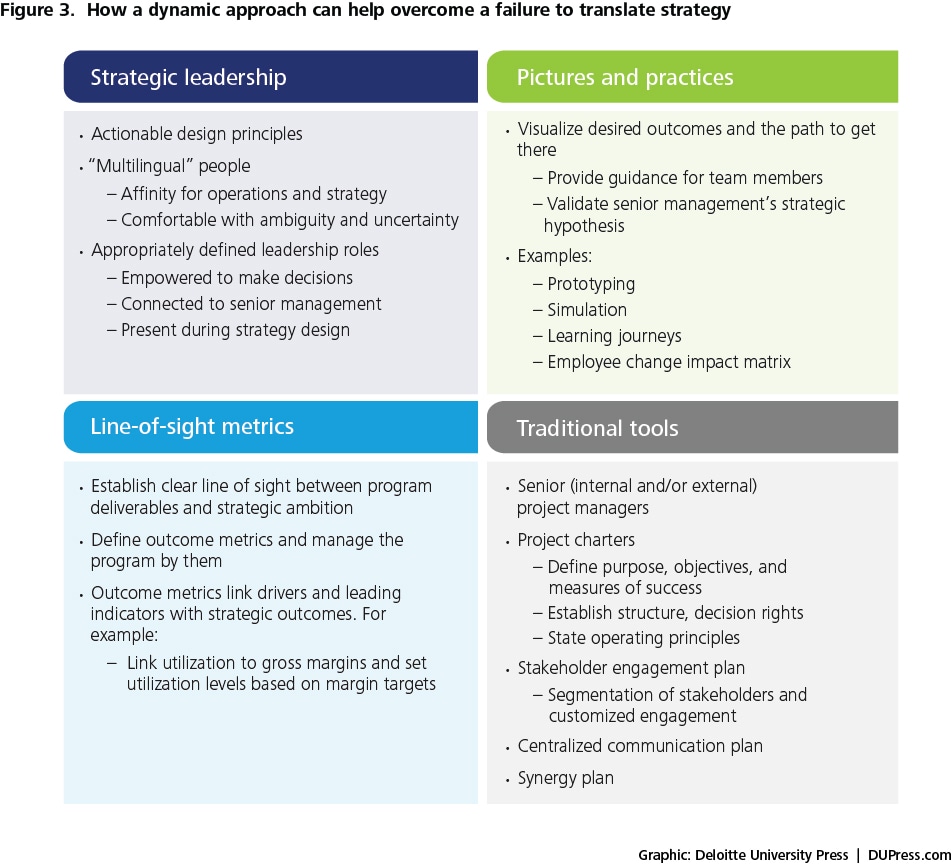

The dynamic approach addresses the translation problem on multiple fronts, beginning with articulating actionable design principles (figure 3). Design principles provide direction to implementation teams without being overly prescriptive; they represent an intermediate level of detail about what is meant by some aspect of the strategic ambition. For example, actionable design principles related to the ambition of becoming customer-centric might include “Make the first moment of customer contact memorable” and “Focus marketing investments on customer segments disproportionately and sequentially.” By giving the customer-centricity implementation team this type of direction, leaders describe what they want with enough specificity so people know where they should start and how to evaluate what they come up with—but without prescribing exactly what the solution should be or how to create it. Thus, the implementation team has sufficient direction but maintains the freedom to be creative and adaptive.

Staffing the implementation effort with people who have appropriate strategic perspective is also a key to translation. For an organization to make downstream implementation decisions that align with strategy, the individuals coordinating and guiding those decisions should be able to think both strategically and operationally. They should be able to translate abstract conceptual ideas and intentions into practical, concrete decisions and choices, and be entrusted to make good judgment calls in response to what they learn along the way. Whereas an administrative approach to implementation features managers whose skill sets are rooted in traditional project management tracking and coordination, a dynamic strategy implementation approach is led by “multilingual” leaders skilled at seeing how operational choices impact strategic outcomes. Such leaders may ask, not only if they are tracking according to plan, but also whether what they are building looks like what the organization aspires to and whether any particular implementation choice will lead to the desired strategic outcomes.

Dynamic strategy implementation demands a different kind of leadership attention as well, with consistent focus on managing for outcomes, not managing to milestones. This requires the leaders who devise the strategy to play expanded roles in implementation, from effectively influencing upstream strategic choices with a knowledge of the implied implementation challenges, to demonstrating judgment in when to engage senior executives for strategic input in key downstream implementation choices. It demands that leaders intervene when employees revert to old behaviors, and provide clarity and support to help employees learn new skills.

A dynamic approach to strategy implementation further emphasizes the use of visualization tools such as scenario development, storytelling, simulation, and prototyping to translate intangible strategy ideas into concrete guidelines for action. For example, the abstract idea of “customer-centricity” may be translated into stories about the specific customer experiences the organization must deliver—such as being able to access the company’s website seamlessly on any kind of device or engaging with the company in the development of new products or services via social media. Similarly, simulation or prototyping may help employees visualize key risks and barriers when planning an implementation in an uncertain or unknown environment—for example, when a company with predominantly North American experience plans a global expansion.

Finally, a dynamic approach requires the use of metrics that specify a clear line of sight between program deliverables and the desired strategic outcomes. For example, target implementation metrics should go beyond specifying “5 percent improvement in employee satisfaction” or “7 percent increase in plant utilization” to explicitly link those goals to larger strategic outcomes, such as “10 percent reduction in employee turnover and associated recruitment and onboarding costs” or “3 percent improvement in gross margin.” This linkage could enable the organization to validate which factors truly drive performance while educating employees on how their individual actions affect organizational outcomes. Moreover, line-of-sight metrics may provide a clear measurement vehicle for assessing and preventing loss of value throughout implementation by enabling more real-time tracking through the implementation process.

Dynamic strategy implementation demands a different kind of leadership attention as well, with consistent focus on managing for outcomes, not managing to milestones.

Adapt to rapidly changing conditions. Conditions change, both internally and externally. Thus, companies should be prepared to course-correct and sometimes even change course as they implement strategy.

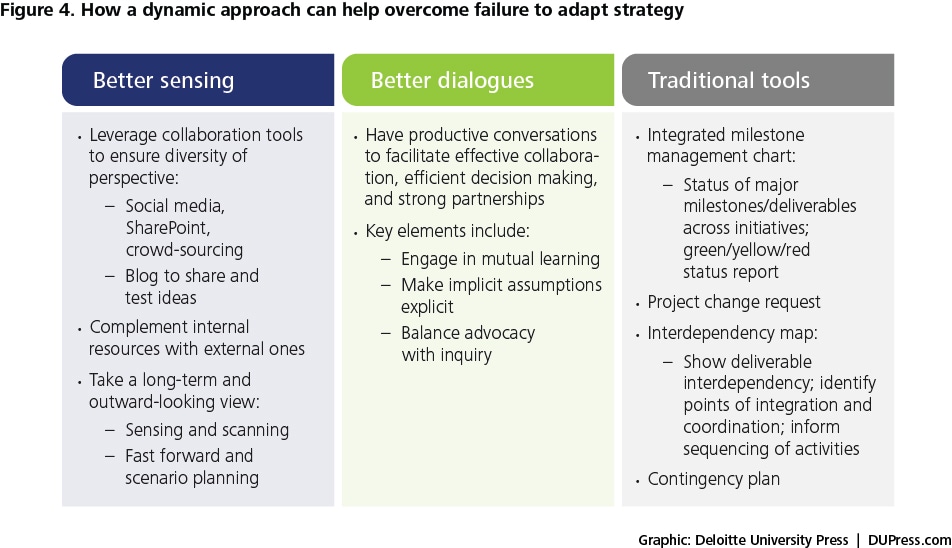

A dynamic approach to strategy implementation enables such flexibility by emphasizing learning throughout implementation (figure 4). Instead of viewing the implementation effort as a change program to be managed and “done to” or “pushed through” the organization, the dynamic approach builds in mechanisms for course-correcting and learning. For example, the dynamic approach seeks to improve leadership’s contextual awareness, soliciting diverse perspectives through a variety of collaboration tools—from social media platforms to crowdsourced improvement ideas to blogs and other engagement channels—to share and test ideas in their early stages. It leverages scenario-planning and environment-scanning tools to anticipate changes on the horizon. And it emphasizes the importance of productive conversation techniques to facilitate more effective collaboration, more efficient decision making, and stronger partnerships with key constituents.

Dynamic strategy implementation also requires a different response to problems that arise in implementation. The traditional approach adopts a “heads down” mentality, focusing solely on the question of “How can we get back on track?” and throwing additional resources at the problem until it is resolved. In contrast, the dynamic approach calls for greater attention to understanding, “What should we learn from the fact that we are off track?” It allocates additional expertise to assess whether the problem is a detour requiring rapid course correction, or whether it is instead a leading indicator that a change of course is in fact required. This “heads up” perspective may enable leadership to adapt and improve the implementation plan in response to changing conditions and new information, and reduces the risk the organization could find itself at point B when it should have changed course and aimed for point C instead.

The dynamic approach calls for greater attention to understanding, “What should we learn from the fact that we are off track?”

Ingersoll Rand, a global diversified equipment manufacturer, illustrates how companies may overcome the challenge of adapting their strategy to changing conditions. In recent years, Ingersoll Rand’s direct inputs—including aluminum and zinc—have experienced rapid inflation. Historically, the company had struggled to adjust pricing to cover material inflation to satisfy customers’ needs for competitive pricing and maintain market share. The company’s CEO determined that his business leaders had to become more adept at value management, particularly in terms of covering rising input costs while increasing value for customers to avoid losing market share. Doing so would be essential to the CEO’s overarching strategy of growing organically by beating competitors on the basis of efficiency and deriving optimal value from the company’s existing assets, people, and technology. To achieve these goals, the company launched a program focused on intelligent, adaptive pricing strategies. After carefully analyzing trends related to its key direct inputs, Ingersoll Rand estimated the amount of inflation the company likely would face in coming years, and then put in place a new approach to value management and pricing that would cover this predicted amount while generating more value for customers.

One of the key success factors for the implementation of this new approach was the company’s willingness to adapt several long-held beliefs to a new reality. For instance, by demonstrating that cutting price did not have a reliably positive impact on sales volume, the company’s leaders were able to reverse one central tenet of Ingersoll Rand’s previous approach to pricing. The company also built a diverse portfolio of cost-saving opportunities that it could pursue if and when inflation exceeded its estimates.

Despite this well-designed, well-executed program, leaders still found it difficult to address the key nonstatic variables of direct material inflation, improved customer value, and sustained market share. Whereas the company’s experience in material sourcing enabled leaders to be confident that they were getting the best possible pricing for direct materials, they were still unable to keep pace as material costs dramatically increased and customers became even more demanding.

The CEO held steady to his goals, but realized that he and his team would have to adapt their approach if they were to succeed. After an extensive objective assessment of their situation, they determined that the company would need to transform its value management and pricing capabilities. In particular, the management team determined that the company needed to improve its capabilities in three areas: customer segmentation and pricing analytics, customized market segment and customer value management strategies, and effective program management. Acting on these insights, they found new individuals to fill key roles, including the global program executive role. They assigned experienced resources to all priority market segments and customer relationships and launched a centralized analytics team to provide upgraded support to prioritized businesses around the world. And they did all this while holding steady to their original performance objectives.

With this highly adaptive strategy in place, Ingersoll Rand was able to keep up with inflation and improve the value delivered to customers. The company generated enough additional revenue and margin growth to exceed direct material inflation’s impact on the business. In addition, the company took a giant step forward in building pockets of sustainable capability in value management, including strategic pricing, market segment and customer awareness, and customer-focused product management.

Sustain the strategy by building organizational capabilities. Sustaining implementation changes over the long term requires investment in organizational capabilities. As can be observed by the decisions of some companies, the behavioral changes required by a new strategy may not stick until they are embedded into a company as enduring organizational capabilities.

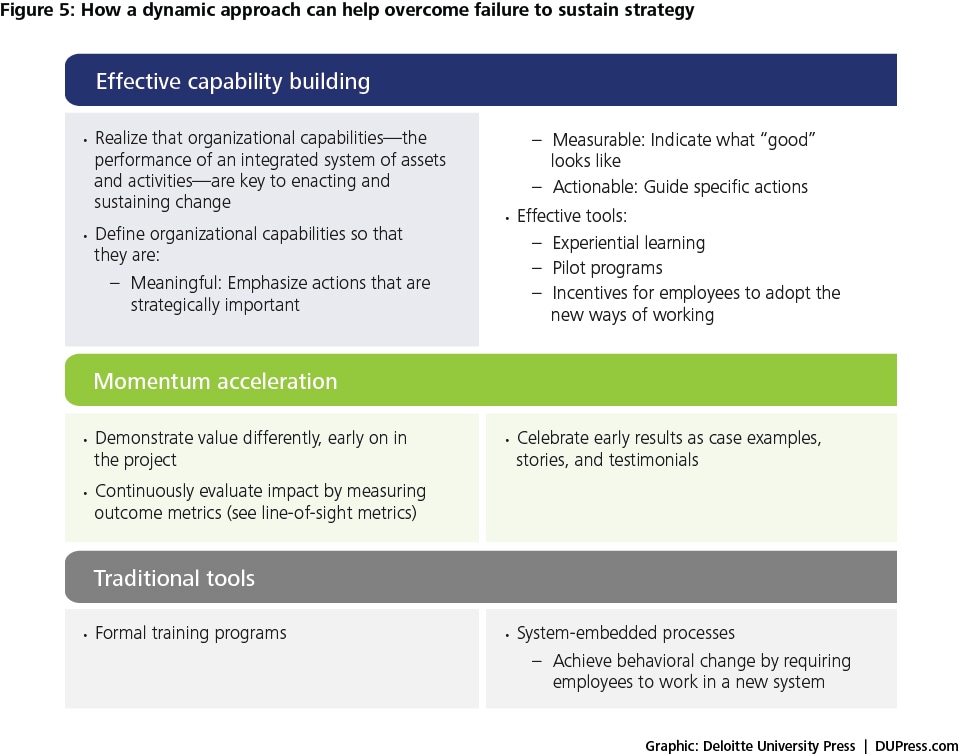

By investing in helping individuals develop the new skills and competencies required by the strategy, the dynamic approach increases the likelihood that the strategy implementation effort will not be a temporary, isolated event. Rather, the effort results in a sustained, long-term improvement in the organization’s performance (figure 5). Building organizational capabilities requires significant effort, from clearly defining the desired capabilities (at a level of precision that links those capabilities to strategic outcomes, enables effective measurement, and guides individual actions) to diagnosing the current level of organizational capabilities to designing the integrated system of assets and activities that builds and sustains these capabilities. Capability-building efforts may also include experiential learning programs focused on improving individual competencies and incentive redesign efforts that encourage employees to adopt new working behaviors.

Dynamic strategy implementation can also help address the organizational resistance that often torpedoes implementation efforts. Whereas traditional approaches typically require significant up-front investment over many months before showing results, the dynamic approach adopts a different mix of implementation activities in the initial stages, emphasizing activities that set the stage for organizational learning (for example, demonstration projects, pilot programs, and applied learning programs). By experimenting with small-scale actions that may later be scaled across the organization, the dynamic approach produces concrete deliverables and value in the early stages of an implementation effort, increasing learning, buy-in, alignment, and enthusiasm across the organization.

PNC Bank illustrates how a dynamic approach to implementation can sustain a strategy. For consumer-facing companies in particular, a strong brand is a key foundation of lasting differentiation and customer loyalty. Thus, PNC’s CEO embarked upon an effort to ensure the bank’s brand would be consistently applied and embodied by employees throughout the organization—even as the firm engaged in substantial inorganic growth.

PNC launched a two-part strategy to achieve this goal. First, the bank developed a comprehensive blueprint outlining the structure of the brand organization, the tools it would use to disseminate the brand message, the skills it would need to do this effectively, the processes it would use, and the ways it would interact with the rest of the organization.

PNC then enacted what it called a “brand cascade.” The bank held a series of highly interactive meetings with senior leaders throughout the firm to teach them the core principles of the brand and what it meant to their aspect of the overall business. These leaders—equipped with in-depth training—helped PNC carry that message down to the next-lowest level in the organization. This process continued until all levels of the organization were fully aligned with PNC’s brand promise. Because the bank put in place a microsite and sophisticated tracking processes, it was able to ensure that all designated employees had successfully completed the training.

This program has done far more than just improve internal alignment with the brand. When PNC acquired National City Bank, its employee roster nearly doubled overnight. The tools and processes developed for the brand cascade contributed to PNC surpassing all of its integration targets, including getting its new employees on the same page, in just 18 months. This new approach to sustaining the bank’s brand promise and customer-facing strategy could help PNC integrate additional acquisitions in years to come.

Putting it all together: Creating the strategy implementation office

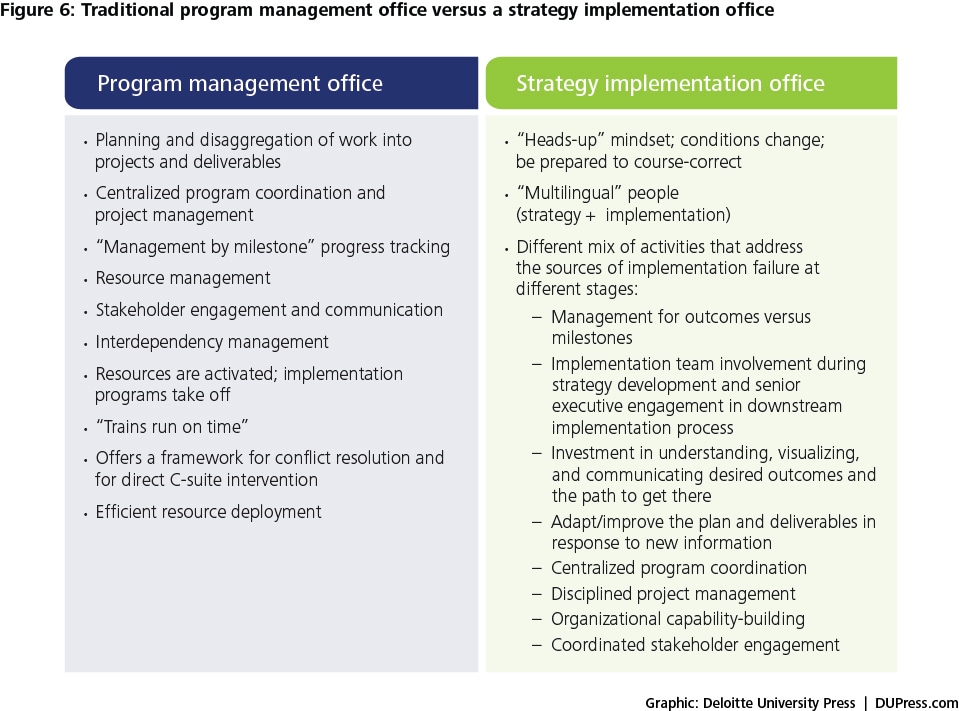

One of the keys to the success of a dynamic approach to strategy implementation is the strategy implementation office (SIO). The SIO provides valuable support throughout the implementation effort—support that differs considerably from that provided by the SIO’s counterpart in traditional implementation efforts, the program management office (PMO) (figure 6).

For example, a typical PMO plans and disaggregates work into a series of discrete projects and deliverables, and measures success by how well the organization achieves specific milestones. A PMO is highly focused on deploying and managing resources as efficiently as possible, and discourages deviation from predefined schedules and timelines to avoid impediments to reaching point B as quickly and efficiently as possible. “Keeping the trains running on time” is the PMO’s mantra.

Conversely, the SIO sees its job more as “getting the trains to the right destination.” The SIO operates with a “heads up” mindset, always conscious of changing conditions and prepared to adapt the plan and deliverables in response to new information if necessary. Rather than tracking progress by milestones, an SIO invests in understanding, visualizing, and communicating desired outcomes and the path to them. Unlike a PMO, which is generally staffed by project management experts who execute work delegated to them by leadership after the strategy is created, an SIO employs professionals versed in both strategy and operations who participate up front in strategy development. An SIO also facilitates the involvement of senior executives in downstream implementation choices to help ensure that nothing is lost in translation. Finally, an SIO helps build new organizational capabilities to ensure that the new strategy and desired behaviors endure.

In short, the SIO embodies the perspectives and skills needed to adopt a dynamic approach to strategy implementation—and thus reduces an organization’s chance of failing to effectively translate, adapt, and sustain its new strategy.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.