GE FirstBuild has been saved

GE FirstBuild Building community with the crowd to speed innovation

John Hagel III United States

John Hagel III United States John Seely Brown (JSB) United States

John Seely Brown (JSB) United States Maggie Wooll United States

Maggie Wooll United States Andrew de Maar United States

Andrew de Maar United States

How can a venerable appliance manufacturer, dependent on traditional processes, compete with nimble start-ups? The FirstBuild workgroup uses seven of the nine practices to bring new and innovative products to market faster. The key: an online and physical co-creation community.

GE Appliances—now a Haier company—has long been a major player in the home appliance market.1 While the company has traditionally produced high product volume at a low price, it found itself facing smaller, more nimble competitors. With a long product-development cycle, the appliance company struggled to move fast enough to keep up with changing market demands and compete with more cutting-edge offerings.2

The workgroup: FirstBuild

To address the challenge, GE Appliances employees Kevin Nolan and Natarajan Venkatakrishnan founded FirstBuild in 2014 and began to build an online and physical co-creation community to develop products in a new way. FirstBuild meets our key criteria for a frontline workgroup:

- Size: Today, FirstBuild is a workgroup of 23 people, with a variety of skill sets. This is somewhat larger than most workgroups.

- Sustained involvement: Members of the FirstBuild workgroup were recruited from both the GE Appliances’ core and externally, but they are now fully dedicated to FirstBuild. They spend all of their time working together on an ever-changing set of activities to bring new consumer products to market more quickly.

- Integrated effort: The products are developed and brought to market through the integrated effort of the full workgroup. Although group members take on different intersecting roles according to each product’s needs, and some tasks are independent, the group’s interactions can’t be specified in advance and the bulk of the product development work can’t be done individually. Workgroup members are physically co-located in a separate facility centered on a “microfactory.” Here, amid machines and tools and surrounded by recent products and projects, the workgroup prototypes and tests its products.

Learn More

Explore the practices and case studies

Read an overview of the opportunity

Download the full report or create a custom PDF

In entering a space inhabited primarily by start-ups and individual makers, FirstBuild seems to be blazing a new path for product development and traditional manufacturers—getting innovative products to the market while striving to dramatically cut development time, cost, and risk. Rather than the traditional approach of forecasting demand and developing products internally, without help from others, crowdsourcing and crowdfunding are integral to FirstBuild’s product development, providing immediate feedback about customer receptivity and interest in the product and its features. Crowdfunding can lock in sales before a product enters production, allowing FirstBuild to move where the market takes it more quickly and with fewer resources. The practice also helps predict a minimum product revenue before launch; units sold through a crowdfunding campaign can fund some or all of a product’s fixed production costs. And perhaps counterintuitively, innovating in public can help the group counter competitive threats.

The results: Active user feedback brings innovative products to market faster

FirstBuild was formed with the objective of bringing better products to market faster. While speed and cost are only a part of that goal, they tend to be easier to track and compare than whether the products are getting better. In this case, “better” means new and innovative—the product doesn’t yet exist within the business or the market—as well as what customers want, when they want it.

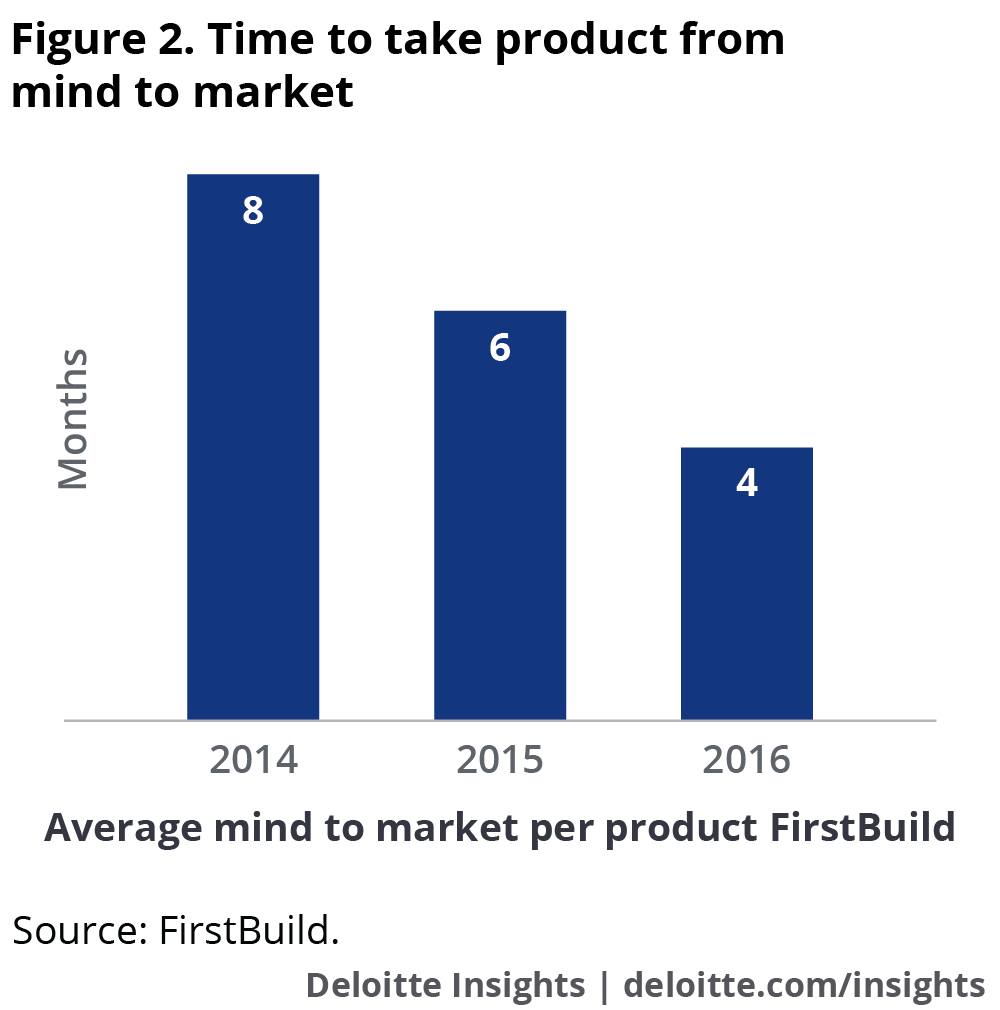

One way the workgroup measures its success is the time it takes for an idea to reach the market—or, as members put it, “from mind to market.” When FirstBuild launched in 2014, mind-to-market could take up to four years at GE. In its first year of operation, FirstBuild was able to bring new products from mind to market in an average of only eight months. Two years later, that metric had shrunk further, to just four months (see figure 2).

But this isn’t only about moving more quickly through a process of development and validation. By developing products in a fast-moving and feedback-rich context, the workgroup is increasing the number of products and ideas it gets in front of consumers, improving its ability to develop better products. In traditional product development, a majority of the ideas and innovations typically never make it to a point at which a consumer could react or interact with them. FirstBuild, by contrast, has as of September 2017 generated nearly three dozen viable product ideas and is testing a new product every month. Eight have been successfully launched into the market. The remainder were killed with minimal investment, having generated valuable insights about what consumers seem to want and don’t want. Interestingly, on certain products, the Appliances core is adopting some of the group’s practices around market-testing prototypes in advance of engaging in a long-term market testing and validation process.

FirstBuild also has far less investment per product relative to the core, with only 23 employees. The all-in cost of getting each new product into the market has typically been less than $300,000, compared with a cost of around $4 million to bring a product to market in the core.3 The group continues to get market feedback faster and cheaper than in traditional product development, while using fewer resources. This lowers the risk and barriers to engaging more continuously with the market to learn from potential customers.

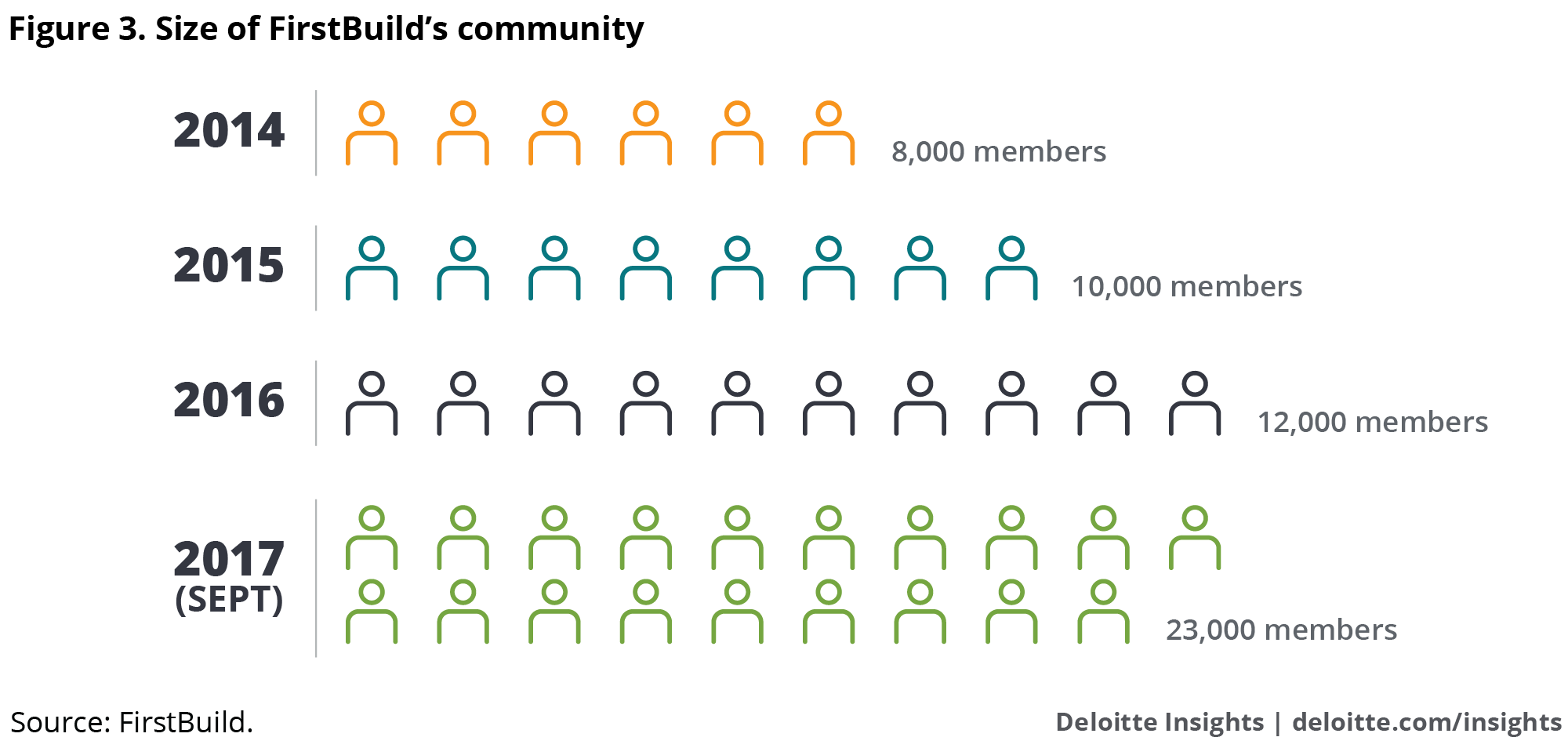

Another sign of the workgroup’s accelerating performance can be seen in the community of funders, buyers, and product development enthusiasts who propose, validate, and test ideas and product iterations on FirstBuild’s open innovation platform. In its first year, that community grew quickly to 8,000 unique users. In the subsequent two years, it grew by another 50 percent and, by September 2017, it had nearly doubled again to 23,000 users (see figure 2), most of them actively engaged in providing feedback on the group’s product prototypes.

Practices in play

The FirstBuild workgroup exemplifies seven key, intersecting practices: Frame a powerful question, Commit to a shared outcome, Maximize potential for friction, Eliminate unproductive friction, Bias toward action, Prioritize performance trajectory, and Reflect more to learn faster.

Frame a powerful question

The FirstBuild workgroup was born out of frustration with traditional approaches to product development that seemed to move too slowly to keep up with the rapid changes in technology and consumer preferences. Two leaders began to reframe this frustration to articulate their belief that there had to be a better way to develop innovative products and get them to market while they still felt new. Two simple questions set the stage: Why did it take so long to develop new products, and why could smaller hardware entrepreneurs develop them so much more quickly? Their answer was equally simple: They needed to test more ideas with more people more frequently. This line of inquiry ultimately led the founders of FirstBuild to ask a more powerful question: What would it look like to get better products to market—ones that consumers wanted while they still wanted them? That question resolved into this powerful question: What if a manufacturer developed products with consumers rather than just for them?

Commit to a shared outcome

FirstBuild’s desire to get its best, innovative ideas in consumers’ hands faster than had ever been done by a large company—to create products that the market needs and wants today—became the shared outcome around which the group crystalized.

Although the group’s co-founders sensed that they could change the game through crowdsourcing key parts of the design and development process and were inspired by a popular crowdsourcing platform, for most members of the group those were secondary means, not ends. Members were excited about FirstBuild for the opportunity to actually have end-to-end product ownership and, equally important, to see whatever they created actually get to market, to watch customers use and interact with those products. In many large product companies, employees are primarily caretakers of existing products with long histories; they own only a very small piece of it. They can also spend an incredible amount of time building and fine-tuning products that never make it past the hurdles to market. With the FirstBuild workgroup aiming to get to market faster, they would have to figure out how to bypass those complex webs of handoffs and stakeholder approvals.

FirstBuild has attempted to set itself apart from the competition (and the parent company) in an important way. Its approach and outcome are inextricably linked, reinforcing a tight bond among workgroup members. “We are one team,” explains FirstBuild co-founder Natarajan Venkatakrishnan. “We all chip in to help each other in times of need. We have a common mission to design the products that are innovative, and that our consumers actively want.”

The group’s aspirations for their shared outcome was quantified in a few key performance objectives that spoke to how different this approach would be: Whereas a traditional product development approach at a large manufacturer might have taken four years and $4 million to bring an appliance product to market, FirstBuild set out to launch new products in only four months, and to get proofs of concept presold, with less than 10 percent of that outlay.

Maximize potential for friction

FirstBuild’s 23 diverse group members came to the workgroup looking to do something more innovative. The group also brought in outside innovators who had little experience in the home appliance space but offered perspectives, skills, and experience valuable to the group’s goals.

Leaders deliberately shaped the group’s culture to be different; they consciously selected members for their ability to think differently, to set their own direction, and to operate with little or no direction from above, even though their curiosity, initiative, and readiness to challenge others might cause friction. In fact, that was the point—too often, in the larger organization, the culture minimized even productive friction. It’s no accident that FirstBuild’s leaders first reached out to employees growing frustrated with the status quo and nonconformists who had ideas for new products and solutions. Now that the group is established, it consciously prioritizes passion over skill when hiring. The workgroup, Venkatakrishnan says, seeks out “people who can take risks, commit to making an impact, go the extra mile, and figure out how to hack things”—from processes to products. The result is a workgroup unafraid of conflict. New ideas are welcomed and tested—or challenged and refined.

In the beginning, leaders thought that it might be enough to get people who were passionate about doing product development differently and had skills that they could use. What they discovered—in large part because many of the initial workgroup members came from the parent company core—is that mind-set and working preferences were also important. For example, one design leader who had been successful in the larger company by dint of being organized and effective at navigating highly structured, hierarchical processes and systems turned out to lack both an openness to change and learning and a comfort with ambiguity. Leaders encountered a few other cases in which they had to let group members go before they figured out what was key to success in this new environment. In Venkatakrishnan’s words: “If they ask, ‘What should I do?’, that’s fine. If they ask, ‘What should I do, how should I do it, and what should I have accomplished at the end of the day to meet expectations?’, that’s a problem.”

In another move designed to maximize potential for friction by bringing together more diverse perspectives, FirstBuild opened its facility to the community at the University of Louisville, whose student center lies just across the street. Students and faculty are given unrestricted access to the full capabilities of the group’s microfactory, which occupies the center of the premises.

FirstBuild also works to engage diverse perspectives in its hiring and staffing, and to attract people who are motivated to make a difference. It actively competes for top talent—not just with other appliance companies but with technology companies more broadly. As one FirstBuild employee explained, “Those guys offer an open and empowering environment—not a do-what-you’re-told type of culture. At FirstBuild, the workgroup is always evolving.”

One way in which FirstBuild continues to attract diverse and passionate participation is to consciously cultivate talent and support members’ careers, even after they leave the group. Operations manager Randy Reeves especially makes it a priority to nurture employees, both current and former: “Many call me and talk about issues they see unfolding and how to advance the next stages of their careers.”

Cultivate friction

As open as the FirstBuild workgroup is in so many ways, it actively cultivates friction by imposing constraints on resources in order to spark creativity. Reeves believes that FirstBuild has been successful in large part because it wasn’t resource-rich and was forced to do more with less. The workgroup was founded without a financial lifeline to the parent company—only a fixed pool of funds. Beyond that, FirstBuild survives on revenues from the products it successfully crowdfunds.

Guided by a shared commitment to getting better products to market, the group embraces friction as long as it moves it toward getting innovative products that consumers want into the market. In every project, members repeatedly challenge the ideas and designs as they move deeper into the product, from idea to use to production to marketing and selling a real product. That expectation to challenge and be challenged is shared throughout the workgroup, and members honor the perspective of the market. The crowdsourcing platform and community is one more way to seek friction. Members solicit challenges from the community at specific stages of development, testing reactions to the concept, certain features, and major iterations of the product. The results from the crowdfunding platform—how many units were ordered, how quickly the funding goal was reached, and the level of interest in the product—provide additional information that can challenge the group’s assumptions and approach for a full market release of a product, including price.

Because they are committed to getting fast external validation, workgroup members tend to be open to friction in the form of conflicting ideas about a given product. They will engage the differing perspectives for a time, but if they reach an impasse in which two approaches seem irreconcilable, members move to quickly test one of the alternatives on the platform, generating new information to inform the debate. With limited time or resources invested in any one iteration and the opportunity to keep iterating, the stakes are lower for any individual idea. Members face no organizational repercussions influencing whether they will challenge an assumption or consider a different perspective. Rather than dig in their heels to defend an idea, members know that they’ll have another shot at improving the solution if the market invalidates a given approach. Take the group’s chewable-icemaker project. Initially, members staged an online challenge about the icemaker and got 30-plus designers to weigh in. Working with an industrial designer, they developed a preliminary design, with a large central opening that looked good but reduced the capacity. Then they began iterating on that design while getting deeper into its complexity. They involved people who had different depths of knowledge to play with the possibilities while also imposing constraints: How could they double the capacity, what would be attractive on a kitchen counter, what could be produced for a certain price point, what would be easiest to use, what would create the best ice, etc. This happens in large companies as well, of course, but the long time lines and institutional/structural barriers often mean that a designer has only one chance to influence the design; as a result, people often fight for their own contributions rather than broadly considering others’ ideas.

The experience with the very first product that FirstBuild developed, a water pitcher kit, seemed to help to cement the group’s commitment to seek out and cultivate productive friction in service of making better products. Potential customers seemed to love the idea of the pitcher, and group members assumed that people would modify their existing refrigerators to accommodate it. It turned out that there was less of a market for tinkering with existing appliances than the group had thought. They hadn’t sought out disconfirming viewpoints or validated this major assumption and were swayed by their own enthusiasm for tinkering; as a result, they made an error that might have been avoided if they had invited people to challenge the group’s assumptions.

Eliminate unproductive friction

No path is entirely smooth, naturally: Bringing aboard those who buck the traditional corporate mold carries a potential for unproductive friction, making it crucial to create a common language and drive toward common goals.

One FirstBuild employee likened the possibility of getting sidetracked by unproductive friction to “putting diesel into a car that only takes unleaded fuel—before you know it, you start having engine trouble.” In this analogy, the diesel is someone at FirstBuild falling back into the parent company’s mind-set and not pushing the group to be better or embrace new possibilities. The instant such mind-sets arise, group leaders take steps to maintain the culture that has come to define FirstBuild and find ways to reignite members’ passion.

Reeves says the effort to continue to stoke the passion of the group members and embrace the often-strong and conflicting perspectives has paid off: “We’ve really become a family. This organization will live and die based on the success of everyone here. It’s not an individual effort.”

Bias toward action

FirstBuild owes its existence to a challenge—well, perhaps more of an insult. When Ben Kaufman at Quirky, an invention platform that connected inventors with companies, said that GE regularly took four years to design and bring to market so much as a door handle, it caught some GE managers’ attention and inspired the idea for such a workgroup.

One early hurdle: a space to house FirstBuild at a modest price. Group leaders turned to local universities, several of which had long been recruiting partners. The University of Louisville, which was keen on expanding its engineering partnership with GE, proved an excellent fit and offered to renovate a surplus building for the venture. The city government of Louisville, Kentucky, was also supportive of the initiative, and within just three months, FirstBuild was a live operation.

The biggest leap, though, was still to come: How to spur ideas, refine them rapidly, and keep costs low while minimizing the effects of potential failures? The answer came in the form of crowdfunding—specifically, using the Indiegogo platform (used most often by start-ups and independent product designers) to refine ideas, test minimally viable prototypes, crowdfund production, and test consumer demand. If an idea sparked enough interest via preorders, FirstBuild would continue development and take the product to market. Any Indiegogo campaigns that failed to accumulate enough preorders to make production viable could simply be tabled, under the rule of “go until no.” The campaigns, tapping an active and growing designer and consumer community, functioned as a sandbox for rapid development and iteration—and kept down the cost of failure.

Granted, making FirstBuild’s innovation portfolio open meant exposure to competition and knockoffs. To counteract this threat, FirstBuild began focusing on maximizing momentum by minimizing the time and resources needed to learn enough to move to the next milestone. Traditional, R&D-based product innovation often takes years to move from careful study, technology surveys, trend analysis, and consumer testing, but a presales FirstBuild product can be developed in as little as four months. In addition to Indiegogo’s crowdsourcing and crowdfunding capabilities, the workgroup uses social media to gauge consumer sentiment and receptiveness to new concepts for products and features and to better understand how customers actually use the products. While on the surface this may seem intuitive, it represented a massive shift from the way many manufacturers test and bring products to market.

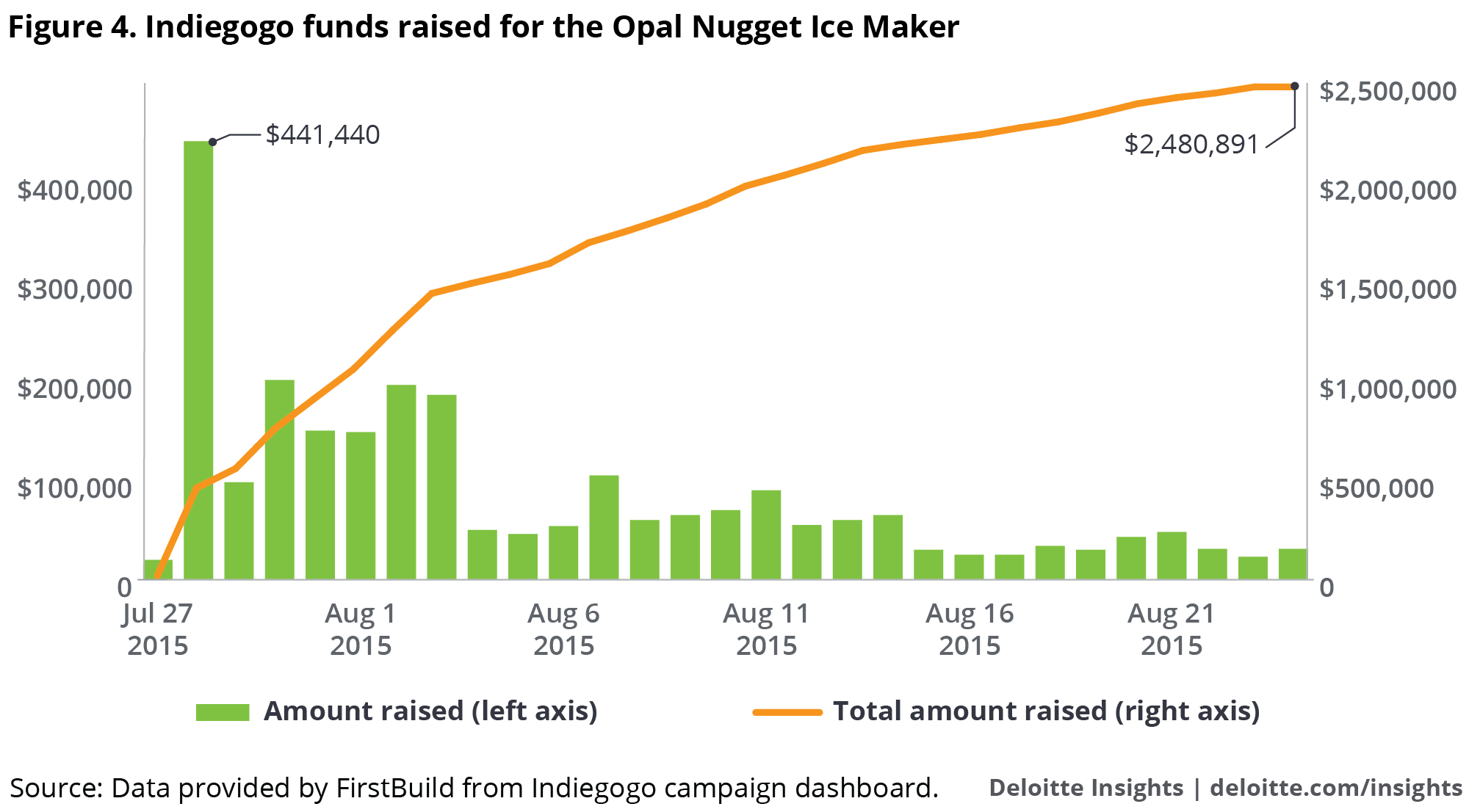

By shortening the product development cycle from years to months, FirstBuild has been able to raise levels of funding more typically seen at a tech start-up. For example, FirstBuild’s second product launch was for the Opal Nugget Ice Maker, a $500 device that produced the same kind of “chewable ice” found at some popular restaurant chains. The Indiegogo campaign raised $500,000 in its first two days and $2.7 million in its first 30 days (see figure 3)—or more than the heavily hyped virtual reality technology Oculus Rift raised on the same platform in the same timeframe.4 In FirstBuild’s first year, crowdfunding for two products covered all of the workgroup’s costs.

But not every product FirstBuild brings forth is a success. In fact, a key element of FirstBuild’s bias toward action is embracing “fast failure”—members recognize that mistakes, while the enemy of efficiency, are the fuel for learning. To date, the group has generated nearly three dozen products and prototypes. Of those, two could be considered highly successful, while six have seen limited success. It takes a nontraditional mind-set to develop, test, and scrap 25 products in two years. But the nature of FirstBuild’s platform requires rapid iteration, and just as important, the culture accepts and encourages failure from which it can learn. While members focus on speed, the utility of that speed is to get more customer input into the product before it goes into production without having the lengthy market-testing phases of traditional development.

Still, failure can be difficult to experience. FirstBuild’s first big failure came from its design for a rapid cold-brew drip coffee maker. Cold brew, which has become widely popular, is less acidic than drip coffee, with a much higher caffeine content, but takes 18 hours to make. FirstBuild’s engineers figured out a way to make high-quality cold brew in only 12 minutes, and members embraced the idea, assuming that it would outperform every other product they had launched. But to their surprise, its Prisma coffee maker’s performance on Indiegogo was subpar. After failing to raise its goal of $150,000, FirstBuild pulled the product and returned backers’ money.

The cost of that failure? A mere $40,000. How long did it take to get a sense of potential sales? Four months. Normally such an outcome might end careers. At FirstBuild, there was very little reaction or repercussion. It turned out that there had been two camps in Prisma’s development: One camp argued that at $300, the coffee maker was too expensive; the other camp disagreed. Since the $300 advocates lost their bet, the team is regrouping on it and coming out with the $100 coffee maker. Every member of FirstBuild was dedicated to learning from failure, and to moving forward to create an even better product in the future.

Prioritize performance trajectory

Rather than focus on quarterly financial results and ROI, the FirstBuild workgroup needed to think in terms of short- and long-term performance. Product innovation, the way the group does it, has no set quarterly or even yearly horizon; it can be far faster or slower than that. Members focus on the trajectory of the metrics that seem most important to getting new products the customer wants to market while the customer wants them.

To do this, FirstBuild tracked two sets of metrics—one focused on financial results for the parent company, the other showing what members believed mattered most to the group itself. The second set showcased data, including how fast the FirstBuild community was growing, what the engagement levels were, and the quality of products under development (measured by the response to products, such as number of preorders and time to funding goal on the platform, along with social enthusiasm of buyers of the product). These were important metrics, albeit numbers without an immediate, tangible financial result tied to them.

Members have set goals around these metrics and pay attention to how they are progressing against those goals. The time-to-market metric, in particular, gets attention in part because it is trackable and in part because frustration with slowness helped inspire the workgroup in the first place. Over the past three years, though, as the group has reduced time to market, members have developed a better sense of how to track metrics that matter to developing better products and developing with consumers. The community’s size, engagement, and the number of products and prototypes released are important indicators that get past simply tallying the revenues from the group’s successful products. They sacrifice some short-term results, continuing to push boundaries with new product types and focus on reframing risks so that they can act to learn rather than play safe to avoid failure. Again, the product that members thought would be the group’s most successful—the Prisma coffee maker—failed, while a product they were less sure about, a $500 icemaker, generated more than $2.7 million in presales. With each product, FirstBuild learns more about developing what the consumer wants.

Reflect more to learn faster

Over time, FirstBuild has continued to refine how members take an idea and transform it into a product. Initially the group’s approach was, if anything, perhaps too focused on feedback, with community members asked for input at every step. Though it may sound counterintuitive, today the workgroup aims to reduce how much it communicates with the community in favor of asking for more targeted feedback where it matters most on the product. This generates higher-quality community participation and gives the workgroup better input into product development.

Take one of FirstBuild’s early products, a filtered water pitcher that would automatically refill in the refrigerator. The group pitched it as an add-on kit that customers could use to modify their current refrigerators—and found less enthusiasm than anticipated. Upon reflection, workgroup members realized that they had missed some obvious warning signs from the crowd. As Venkatakrishnan put it, “We made one big mistake: We assumed that everyone who was part of our community had a passion for appliances, just as people do for cars. In reality, we couldn’t have been more wrong. People don’t just wake up and say, What can I do to my refrigerator today?” The silver lining is that the group shared the design with the core of GE Appliances, which worked to embed the pitcher as a standard feature in new refrigerators; as a standard fridge feature, customers loved it.5

Today, instead of soliciting its crowdfunding community for feedback at every step, FirstBuild relies more on its own in-house expertise, then institutes spot checks with the community to see which ideas and refinements resonate most. It uses crowdfunding platforms to get a different view into the market appetite for a given product.

While the group’s overall approach has been successful, members are constantly learning and reflecting on what works best in how they respond to market dynamics. With the first few crowdfunding efforts, within a week or so of shipping a product, consumers would begin posting on social media about it: pictures, videos, how they were using it. Members found this experience of being so close to the consumer and getting such direct, immediate feedback totally new—in traditional product development, the end user was many links removed up the value chain. From that point on, members tracked community engagement, including the number of YouTube and Twitter followers, since social media engagement seemed key for market validation.

Members also continually reflect on ways to engage the crowd and garner new product ideas. To date, FirstBuild has sourced more than 1,400 ideas from consumers. It is currently equipped to work on between 12 and 15 full product releases per year—less than 1 percent of the ideas that members generate. Over time, the workgroup has learned more about what could gain traction in the marketplace and which ideas might have a longer runway than others. For example, with this experience and others, members saw a pattern: It was easier and more successful to introduce an entirely new type of product to the market than to modify or evolve something that already exists.

An expanding role

Above all, the members of FirstBuild recognize that developing new products in a new way often hinges on working in new ways, deciding to approach the relationship with the consumer as less transactional, more collaborative. With a new appreciation for the role the public can play in shaping ideas and providing timely, targeted feedback, GE Appliances now aims to expand market-facing development on a wider scale, creating a new crowdsourcing platform called Giddy (“in honor of the elation of invention”) for products developed by the larger enterprise.

One realization FirstBuild members had was that, with the group focused on appliances, the skill sets and ideas from their community were limited. The current plan: Take the community of more than 20,000 people who are currently part of FirstBuild’s efforts and expand it to 100,000 from many different industries—from medical devices to software to engines—who could “solve any kind of problem,” bringing corporate crowdfunding to the mainstream and serving as a platform for broad product creation.