sparks & honey culture briefing group has been saved

sparks & honey culture briefing group Embracing a diverse world to sense and make sense of cultural signals

07 March 2018

John Hagel III United States

John Hagel III United States John Seely Brown (JSB) United States

John Seely Brown (JSB) United States Maggie Wooll United States

Maggie Wooll United States Andrew de Maar United States

Andrew de Maar United States

How can a cultural consultancy transform thousands of daily data points into useful, forward-thinking insights for clients? New York-based sparks & honey uses six of the nine practices to make sense of all the signals and stage a daily briefing that aims to enlighten—and to spark future discussions.

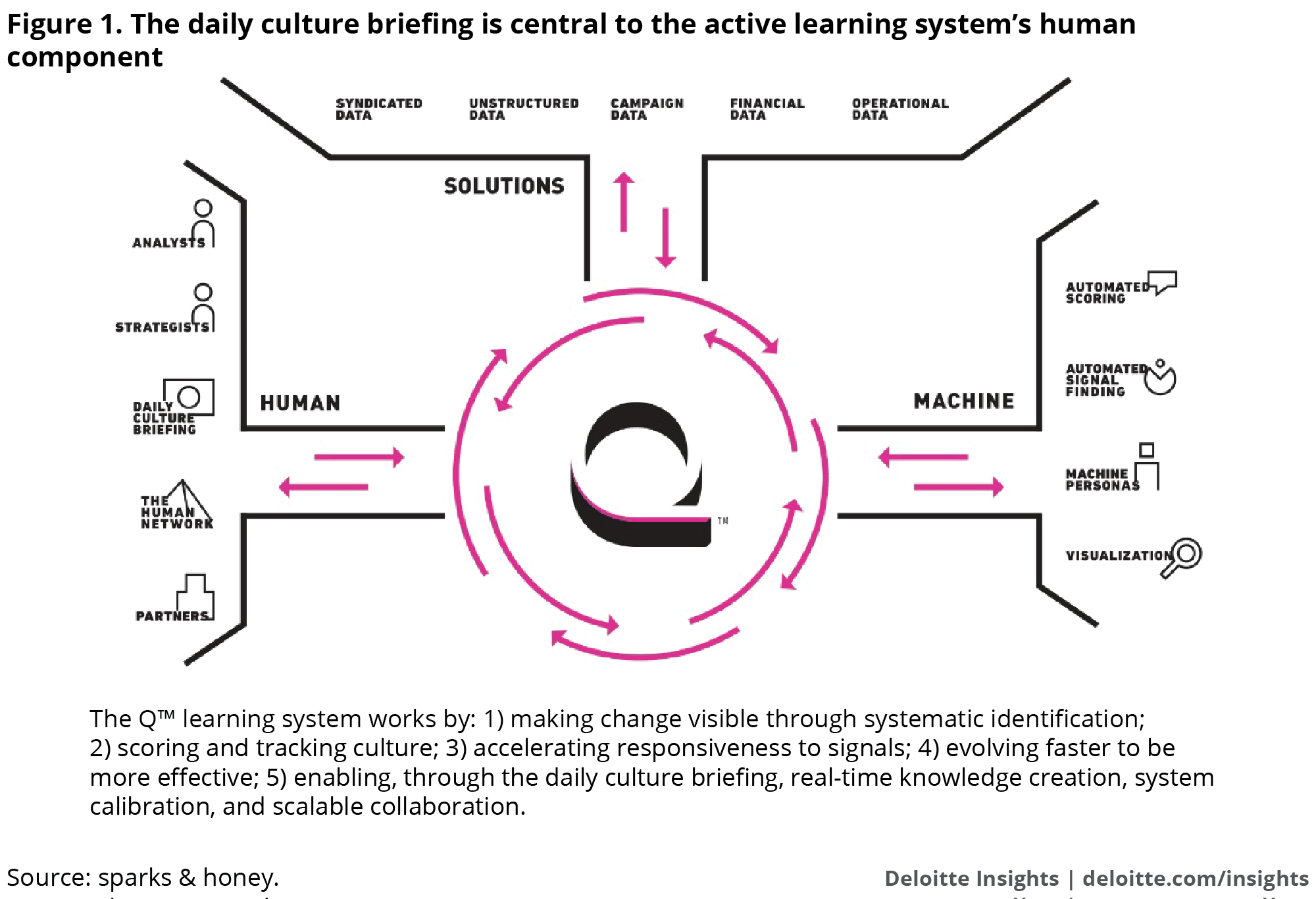

New York-based sparks & honey (s&h) is a big-thinking cultural consultancy that aims to tackle global challenges using social and data sciences. Founded on the belief that humans alone cannot accomplish this mission, s&h has built an active learning system, called Q™, that brings together people and machines to make sense of the world in real time. The firm’s culture briefing workgroup delivers the daily briefing at the heart of the s&h cultural intelligence system, helping to make sense of thousands of data points in near real time. The cultural insights generated by the briefings helped the consultancy achieve 70 percent annual revenue growth between 2014 and 2016 as the workgroup improved how s&h senses and makes sense of signals.1

Learn More

Explore the practices and case studies

Read an overview of the opportunity

Download the full report or create a custom PDF

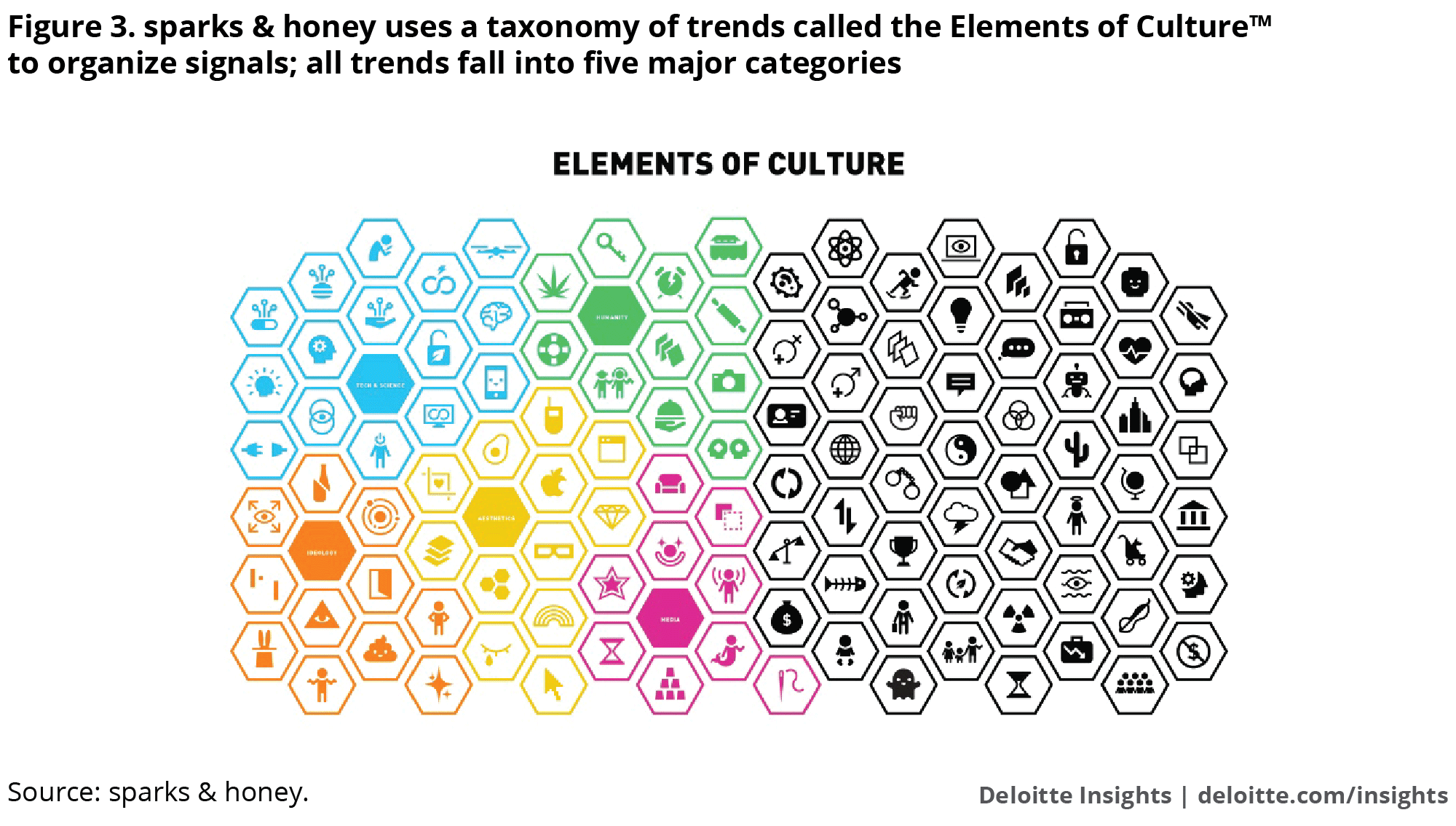

The firm looks to identify, name, and categorize shifts across culture before they become mainstream trends, then aims to help clients understand and shape them using a trend taxonomy. Broadly, sparks & honey takes the world as unstructured data, a mix of fast culture and slow culture: everything from a tweet, new semantics, viral video, to new policy, academic research, patents filed, start-ups established, and VC deal flows. Through its daily report, the culture briefing workgroup gives structure to the data by tagging individual items (“signals”) to the trend taxonomy and by applying scoring methodologies as they monitor trends over time.

The consultancy’s “culture newsroom” operates 24/7, 365 days a year. The firm draws on a wide variety of thought leaders and cultural observers around the world2 and applies a combination of proprietary methodologies, tools (see figure 1), algorithms, and human insights to provide cultural intelligence, data analytics, and strategies to a diverse range of organizations and brands. Organizations from McDonald’s to DARPA3 work with the consultancy to uncover and act on these cultural shifts.4

“We translate culture into real-time opportunities for brands,” says CEO Terry Young. “Some of those things are growing at a very fast velocity, and some of those things you should be aware of if you are going to continue to shape your organization two to three years out.”5

With a mission to “open minds and create possibilities in the now, next and future for brands,” s&h aims to be a filter for, and presenter of, ideas that influence and shape culture. Commenting on the consultancy’s 2015 report on the emergence of a new language to describe the gender spectrum, for example, The Advocate noted that “within its marketing recommendations lies a thought bomb of radicalism that could truly change society.”6 Other reports on mainstreaming marijuana, the influence of Gen X in middle age, and similar shifts reflect the firm’s scope and ambition.

The workgroup: Culture briefing

At the heart of the firm’s business, the culture briefing workgroup brings the consultancy’s cultural intelligence to life and keeps client teams up to date on cultural trends. This group meets our criteria for a workgroup:

- Size: The core group includes seven members, including two co-briefers, two data scientists, a moderator, a human network connector who tags signals to specific advisers for more research or context, and an illustrator who creates visualizations of the workgroup’s daily output.7

- Sustained involvement: Workgroup members spend the majority of each workday working together to curate, present, and analyze the signals discussed in the daily briefing.

- Integrated effort: Using the firm’s bespoke active learning system, Q™, members mine trend data, devise research, monitor defined “signals,” and curate the cultural briefing event for the entire s&h organization (located in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago) as well as the global scouts and guests, including clients, who are attending live or watching the live stream. The group acts collaboratively in doing most of the work of selecting signals, pulling the presentation together, and analyzing briefing insights.

Each day, members comb through the database of “cultural signals”—anything from “a tweet, song, or meme that’s spreading fast, to popular news articles, research papers and patent files, to changes in public policy or emerging tech”8—to review additions made in the past 24–48 hours, then choose around 30 items to present at that day’s company-wide briefing. These signals—which can range from trends in consumption of insect protein to early signs of the “premiumization of air” and Braille on clothing to a story about how dogs could be considered practice babies—are selected based on several factors. For example, does a particular signal have high energy? Does it help establish a pattern based on other, recently discussed signals? Does it introduce a new concept from the fringe of culture? Does it introduce or affirm a cultural tension (the coexistence of opposite trends)?

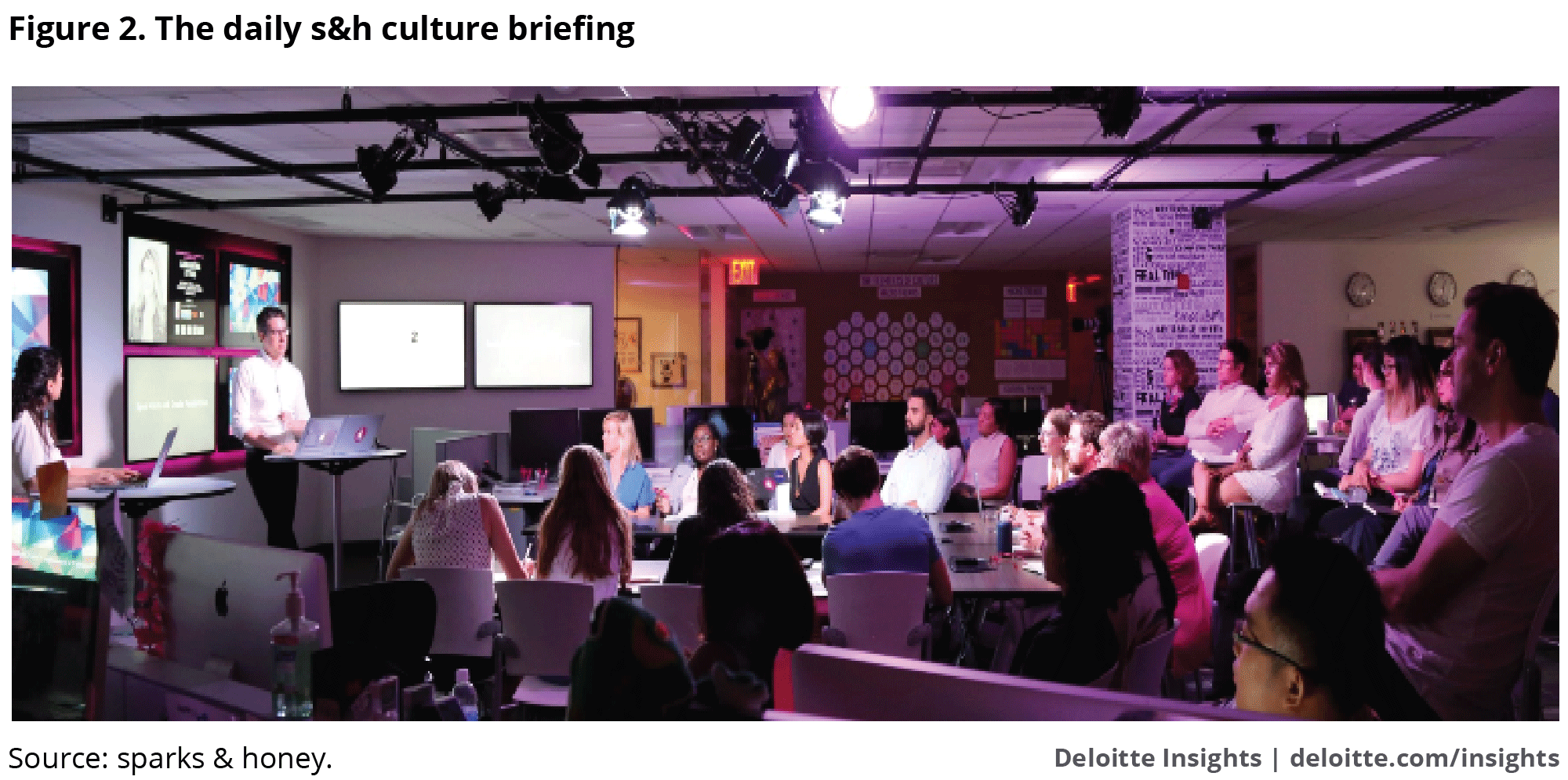

Not only does the workgroup curate signals—it seeks to present those signals in an engaging way that provokes broad and productive responses from participants beyond the workgroup. Members decide how to present the day’s signals to be succinct yet evocative; visuals are often just as impactful as the language, often featuring images taken directly from the source data. The goal of both is to engage the minds of the broader consultancy, the global network of culture scouts and advisers, and any guests who have come to unpack cultural signals through discussion.

The consultancy relies on the noon briefing to fuel its client work. By exposing participants to ideas, data sources, and interests they might otherwise miss, the briefing helps counter personal or institutional biases. The format “allows us to extend our analysis across categories, time and space, to take multiple sources of unstructured data, immediately add structure, and then use real-time and cross-discipline discussions to quickly develop insights and identify patterns,” says COO Paul Butler. “The briefing is also a forum to examine and monitor cultural tensions, a key methodology in our process. We observe that opposing trends can manifest and move simultaneously in culture.” The format is a way for the consultants to come together to identify and unpack various tensions. They then work with clients to identify how, when, and where they may lean into one or another side of a cultural tension.

In this case study, we consider practices at two levels: within the briefing workgroup itself and among the 50-plus participants in the daily briefing session. Because the larger s&h organization both relies on the output of the daily briefing and also participates in it, while the briefing workgroup creates the daily briefing and also participates in it, some practices are used both within the workgroup (in developing and preparing for the daily briefing) and in the briefing itself. Although we are primarily interested in what happens within the workgroup itself, in this case, it isn’t always a clear distinction—and some practices are more visible in the context of the one-hour briefing even though the workgroup also uses them to do its work.

The results

As a workgroup output, insights may seem pretty nebulous. But the quality, timeliness, depth, breadth, and cultural relevance of those insights provided to clients—accompanied by thought leadership, analysis and strategies—are what generates revenue for the organization. The daily culture briefing—both through the insights it generates and the way it trains the algorithms and the staff to recognize patterns and identify trends—is a key driver of s&h’s ability to deliver the type of work that its clients value. The consultancy has enjoyed 70 percent year-over-year increases in revenue for the past three years, and leaders credit effective daily briefings for consultants’ ability to deliver differentiated insights that drive that revenue growth. Over time, the culture briefing workgroup has developed a metric—connections per signal—that members feel has proven to be a useful indicator of briefing effectiveness.

Connections per signal

Given that the daily culture briefing is part of a larger intelligence system at s&h, the workgroup tracks the relationship, importance, and relevance between the signals discussed in the briefing and other parts of the system. For example, does a particular signal connect with other trends? Is it relevant to the work of our advisory board members or other parts of the human network? This metric helps the workgroup assess whether the briefings are effectively expanding the participants’ thinking to better understand human behavior and values in a broader context and inform near-term campaigns and long-term strategies. The average number and diversity of connections made between topics are continuously tracked to maintain what the group feels to be the right balance between quantity and quality for optimal performance—ideally three to five connections per signal discussed during the briefing while still covering a breadth of signals.

The workgroup is core to the organization’s strategy because better briefings lead to more expansive and impactful insights for clients. In a successful briefing, the group might raise comparisons of global markets as indicators of shifts in consumer behavior and human values and look for other indicators of how those shifts might affect businesses and brands across categories. For example, when the automated sensing system added a signal about a difference in luxury watch sales in the United States and China, it led to tracking a broader trend in perceptions of luxury that were beginning to diverge in the two countries.

Practices in play

The culture briefing workgroup exemplifies six intersecting practices: Commit to a shared outcome, Seek new contexts, Maximize potential for friction, Cultivate friction, Eliminate unproductive friction, and Reflect more to learn faster.

Commit to a shared outcome

The workgroup members seek to create an engaging, provocative, and productive briefing each day to make sense of the latest cultural signals mined from across the spectra of life, the Internet, and a human network of contributors from around the globe. The noon briefings gather the entire staff for an hour each day. Typically, the pace is fast, the discussion is deceptively disciplined, and the topics covered can range from funny to serious, trivial to earthshaking. The briefing serves as a space for the consultancy as a whole to sense (and make sense of) a wide range of seemingly disparate trends, but it is also a laboratory of sorts, a place where interesting ideas and innovation can emerge.

The culture briefings are considered central to what sparks & honey offers to clients, and as many clients attend the briefings, it can sometimes be difficult to separate the outcomes—the insights, content, and actions—from the practices that generate the insights. The workgroup’s practices are designed to get better and better at effectively surfacing cultural signals that can be used to make predictions and generate actionable insights and strategies.

Part of the group’s commitment to an engaging, effective, and productive briefing is to get through all of the signals they have chosen to highlight in the one-hour session. In addition to maintaining a certain volume of signals, they also consider their impact on the outcome as a combination of factors:

Discovery of new: Have we exposed and stretched ourselves and our clients to new ideas that can lead us on a path of transformation?

Discussion and discovery of the fringe: We believe that what is happening on the edge of culture is relevant and may be where the future of a business or category may go.

Seek new contexts

All of the s&h staff, as well as the extended global network of advisers and scouts who move through a variety of contexts, are constantly logging and tagging cultural signals into the proprietary database that is part of Q™, as they encounter them. Automated personas—across a spectrum of genders, races, political views, ethnicities, interests, employment, education, age, household composition, and geographies—also tag items to provide additional lenses and bias on culture. The briefing workgroup reviews all the material that has been logged or tagged in the database as an emerging trend or cultural signal each day, curating it for the daily briefing. While the group has no set goal for the number of cultural signals to tag each day, the group is continuously seeking to include and analyze signals drawn from a range of contexts to stay connected to the edges of cultural change, and to help understand and validate trends.

For example, the workgroup might deliberately choose to highlight a story about a Midwestern drone facility, connecting it to ways in which the urban airspace is changing. The group, sometimes with clients, will conduct culture treks—live explorations of cultural experiences and events—as a way to share and gather intelligence. In another example of seeking context, the co-briefers attended a DJ school in New York to learn about curation and presentation from professional DJs. The workgroup recognized the unique demands of the briefing format, balancing an open discussion in a forum that requires structure and order to be effective, and saw direct parallels between that and working as a DJ—threading together individual, seemingly unrelated elements into a coherent whole within a fixed amount of time; managing the energy of a diverse crowd of knowns and unknowns; presentation and performative aspects; and a need to maintain and achieve a certain cadence to make an impact.

For work that is highly conceptual, there’s also a crucial hands-on component. Tracking and observing trends from behind a screen, it turns out, is often insufficient. When one client wanted to know more about camel milk consumption, the briefing workgroup spent time drinking it, going deeper into context, and getting their own unvarnished truth, since—members agreed—blogs and Instagram pictures could not convey the unique experience of drinking the milk. Members also looked at the different kinds of “milk” that have trended in the United States and in other cultures over the years, how long each trend lasted, and which milks found a lasting foothold in the marketplace.

Maximize potential for friction

While the core roles in the briefing workgroup are relatively stable, others are purposefully rotated. Two to three staffers, each representing a different s&h client, join as adjunct members of the workgroup for a few days at a time. These rotating members from the client teams bring new energy, skill sets, and perspectives—along with a client-specific lens—that can change the way the workgroup curates, interprets, and presents signals, as well as how it prepares for and facilitates the briefing. The rotating members inject some discomfort and new friction into the group’s daily work. This can lead to new approaches to selecting the signals or new ways of grouping and presenting them to elicit different responses. For example, a rotating member who represented a beauty client team might know that the client is particularly interested in trends in the 60-plus market and challenge the group to consider longevity in selecting signals. The core members provide a level of continuity, but the rotating members challenge them to avoid the routine with fresh ideas and new client issues.

For the actual daily briefing, the workgroup convenes a diverse array of participants—including global scouts, advisers, clients, and other interested members of the public—as part of s&h’s “open consultancy” concept. The group has even begun livestreaming some of its daily briefings on Facebook, further expanding the range of participants, although it is still experimenting with how best to interact with an open, online audience. The open consultancy has a deliberate business purpose: inspiring productive debate and meaningful discourse with each other and the outside world. By inviting a collection of outsiders into the briefing discussion, the workgroup increases the potential for disagreement and divergent perspectives and new ways of interpreting the signals. Importantly, this can increase the number and depth of the links members can make between signals, since unexpected input may well surface hidden connections, adding real depth and value to insights.

Cultivate friction

In each daily session, the workgroup brings in someone from outside the workgroup to serve as co-briefer. The rotation lets others in the organization see what goes into a briefing and allows the workgroup to get fresh perspectives on the presentation. For example, one co-briefer, a self-described introvert, challenged the bias toward fast, energetic, nonstop exchanges by introducing deliberate periods of silence. Now the workgroup builds silence into work sessions and briefings to encourage people to focus on what’s being said more than on preparing to speak. Structuring silence—building it into the approach—has had the effect of making the interactions less about personal reactions and more about signals and ideas. It has helped shift the briefings away from presentations by people immersed in trends and toward soliciting insights and responses to those trends.

Finally, the workgroup makes it a rule to change the rules regularly—hosting experimental briefings that use new approaches and mediums of exchange on the first Friday of each month. By shaking up the routine, these experiments are designed to force participants out of their comfort zone, which tends to create friction for the group and also for the organization. The members pay attention to whether the friction surfaces insights in new or more meaningful ways or leads to more effective or productive briefings. For example, in one briefing, they used the theme “think like a criminal” as an experiment, with the goal to develop insights beyond norms of “acceptable” (or legal) behavior and values, as a way to stretch the group’s thinking to develop new innovations for security and privacy, new content mash-ups, or other future product ideas. That experiment stuck, and members now regularly use that theme as a framework to challenge preconceived notions or to innovate.

Another example is the workgroup’s introduction of special edition briefings, designed to shake up the dynamic and to bring more outside perspectives into the briefing environment. In these sessions, the group invites external experts from a specific vertical, rather than s&h staffers, to discuss signals and trends. These sessions take on a slightly different personality, since guests are less primed to respond to implicit cues and the accepted practices of the daily briefings.

It is one thing to convene diverse participants, another to draw out those participants’ divergent perspectives and challenges. One way members do this is to encourage participation from a scout or a guest (given that most of the guests are invited by someone within s&h who knows something of their background) when they feel someone may have a different point of view on an issue. The workgroup introduced the role of a moderator in briefings, in part to prompt and stimulate dialogue around the table, between all participants. The moderator’s role was to introduce questions, not back to the co-briefers but to other workgroup members, or directly to guests with knowledge or experience of a topic. That small shift helped reorient the room and achieve a more roundtable-style discussion.

For all that s&h embraces diversity, there are common biases still at play—for instance, all of the workgroup members reside in New York. Rather than fight these constraints, the group defines them in a methodical way, under the theory that exposure and analysis can reduce associated blind spots. All members make explicit their own areas of interest and exposure and try to be transparent about the way these influence their attention and lenses. Each person is expected to add a unique perceptual flair. The workgroup uses the briefing as a tool to continuously expose and explore its own blind spots, and to break its own algorithms to support a broader exploration and engagement in culture. Acknowledging the inevitable biases in an open and nonjudgmental way makes it possible in the daily briefings to complement and counterbalance the perceptions of employees with external participants known to have contrasting backgrounds and biases.

Eliminate unproductive friction

It’s easy for the line between thought-provoking experience and frustrating conflict to blur. For an organization that derives so much value from leveraging perspectives from across a diverse human network, managing the unproductive friction that arises is crucial. Interpersonal conflict, shaming, judgment, and lack of respect can quickly change the environment, making workgroup members less willing to offer, or challenge, divergent ideas or perspectives.

Outside of the briefings, in signal selection, the group tends to favor creating space for more possible perspectives in the briefing by including a particular signal if a member feels strongly about it rather than debate its inclusion. The results in terms of comments, connections, and client tags for that signal can be evaluated afterward and inform signal selection for the next briefing. This builds trust within the workgroup because members all agree to the objective evaluation of the chosen signals in the after-action reflection. Objective data and a common methodology and language for how they categorize and evaluate signals—baked into s&h’s active learning system—helps to dispel potentially unproductive friction that can come from differences of opinion about whether a particular signal is interesting enough for the briefing.

To help mitigate and dispel any potentially unproductive interactions that could drain energy and trust, the briefing workgroup encourages a vocabulary that is more constructive than confrontational, with phrasing drawn from tested nonviolent communication strategies, designed to help all parties and perspectives get heard. For example:

- “I see where you’re coming from, though I think it’s also interesting to consider . . .”

- “Yes, that makes sense. I want to build on that thought . . .”

- “To provide a converse perspective . . .”

In the daily briefing, unproductive friction—such as shaming or judgment—can make participants feel unsafe or unwelcome and less willing to participate openly. The constructive vocabulary has become even more important in the briefings. For example, in a discussion of a signal about an app to help professionals decide whether they should speak up in a meeting, two participants firmly disagreed about whether it was a positive indicator of the trend in “powerful women.” A third participant broke the polarizing dynamic by expanding the discussion, saying, “I see where you’re both coming from, though I’d like to also consider it through the lens of culture . . .” This opened the discussion back up so that members could look for additional connections and interpretations rather than getting stuck in a standoff.

The workgroup also tries to reduce unproductive friction by encouraging the use of nonverbal cues that indicate approval or disagreement, and by allowing quiet one-on-one side conversations so that participants can surface reactions in the moment without interrupting the group as a whole.

It’s no accident that the daily briefing is scheduled at noon, a time when many feel their energy flagging. Many participants find the event so thought-provoking that it provides an energy boost that can carry them through the rest of the afternoon. Notably, the workgroup facilitators work to create “a comfort level with being uncomfortable,” as director of human networks Annalie Killian puts it, in the belief that wrestling with new ideas requires some level of discomfort.

Reflect more to learn faster

In between planning and hosting the daily briefings, workgroup members take time to reflect on the briefings as well as on how effectively the consultancy is deriving insights from the briefings. They also reflect on any new thinking they have about where signals fit within the consultancy’s cultural taxonomy. Every week, they review the week-over-week changes in the briefings and ask key questions: Did we get the most out of our discussion of any new trend or previously uncovered trend? Has a particular key trend changed in ways that are meaningful?

The occasional livestreamed briefings, recorded and made available on social media, have given the workgroup much more information to reflect on and use to tweak and recalibrate. The recordings have been particularly useful input for presenters to replay and review their own performance, compare to tracking metrics, and self-correct to improve the speed, clarity, and set-up of dialogue per signal, as well as how they manage and moderate the conversations. They also get additional perspective on the level of engagement and participation on the signals that might not be apparent while in the midst of running the briefing. The workgroup takes as input the usual metrics of online audience engagement and activity and is experimenting with getting the online audience to provide input and validate or score signals discussed during the live briefings.

In the daily briefings, the aim is to cover as much ground as possible, while unpacking as many unexpected and uncommon insights as possible along the way. Given this challenge, the workgroup has developed two metrics to track as leading indicators to the number and diversity of connections made over the course of a briefing, which is the key indicator of briefing effectiveness. The group is constantly assessing the balance between these two metrics:

Comments per signal. The workgroup uses the number of comments made when a signal is being discussed to assess whether members are going too deep, which prevents the briefing from covering other valuable signals or, conversely, not getting beneath the surface, which prevents identifying patterns or uncovering new ideas. The number of comments also indicates whether participants found the signal provocative, which is related to how much depth and nuance there was to unpack—and how much potential value that signal might offer to clients. Clients will likely derive less value from signals or insights that are straightforward or superficial.

Time spent per signal. The average time participants spend discussing any one signal is another indicator that helps the workgroup balance breadth and depth in the briefings.

As a result of reflecting on the metrics and discussing specific briefings, the workgroup has developed practices designed to make the briefings more engaging and productive. For example, over the course of a briefing, each cultural signal under discussion is paired with another into “builds” that move the conversation forward. The group has found that two to three signals per build help to maintain optimum momentum.

Beyond discussion of individual signals, the workgroup spends time making connections between and among signals to identify emerging cultural intersections. Pattern recognition involves using five meta-categories—technology and science, humanity, ideology, aesthetics, and media—as well as tracking how trends evolve over time. Members wishing to work with insights arising from a briefing write them on sticky notes, then cluster them next to other signals with which they may identify a connection. If a pattern becomes stronger and its clusters grow large enough, it is defined as an “element of culture” (see figure 3).

All of these predictions are augmented and amplified by a set of constantly refined algorithms, which together indicate the impact of any given trend by measuring the interaction of three factors: energy, prediction, and reach. Energy is a measure of how fast a particular signal is moving through the culture. Prediction is an estimation of how long the trend in which that signal is embodied may remain relevant and/or evolve over time. Reach is a measure of how many people the trend is currently affecting, or is forecast to affect over time.

The combination of these three measures defines and shapes where a signal sits in the s&h trend taxonomy—and helps define the related trend as micro, macro, or mega. The consultancy’s proprietary scoring methodology determines whether a trend moves from micro to macro, or from macro to mega, where reach, persistence, and energy define the classification. One example is the rise of yoga pants as mainstream fashion. What first emerged, beyond yoga, as easy attire for active moms eventually appeared as products from luxury fashion designers; in one briefing, s&h accurately predicted that this popularity across many levels would lead to a decline in denim jeans purchases the following year.

The measurement process also provides an opportunity to isolate and compare dimensions of each trend to determine, for example, if one is on the verge of combining with another. Micro trends typically have higher energy, while macro ones have greater prediction and reach.