Getting decision rights right How effective organizational decision-making can help boost performance

12

28 February 2020

Effective organizational decision-making is strongly associated with better business outcomes. Learn what five key attributes organizations can put in place to help their people make better decisions faster.

From setting high-level strategy to allocating budgets to hiring new workers, an organization—or, more accurately, the people within it—makes myriad decisions that determine its actions in the marketplace. Yet as important as it is to get those decisions “right,” a surprising number of organizations lack clarity about just what decisions need to be made, who is responsible for making them, and how the decision-making process should proceed.

Why does this matter? On the face of it, it seems obvious that the lack of clarity around decision rights would tend to hamper timely decision-making and/or compromise decision quality. Recent research bears this out: Getting decision rights “right” is an essential part of high organization design maturity, which in turn is strongly associated with better business outcomes. Of particular note, public companies in the study with high organization design maturity enjoyed 23 percent greater revenue growth over the three years prior to the study than those with low organization design maturity.1

Higher organization design maturity is associated with better business outcomes

Companies with high organization design maturity are …

- 3x more likely to develop new products and services that disrupt markets

- 1.9x more likely to achieve high levels of customer satisfaction

- 1.3x more likely to meet their financial targets

... than companies with low organization design maturity.2

Learn more

Explore the Human capital collection

In a hurry? Read a brief version from Deloitte Review, issue 27

Download the issue

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

It’s not hard to intuit why decision rights can have such a large impact on performance. Research shows that, in many organizations, ambiguity surrounding who is responsible for making a decision (or decisions) is a primary cause of delay in the decision-making process.3 Such delays cause the organization to lose valuable time across the gamut of its pursuits: developing new products, updating current products to meet changing consumer demands, entering new markets, and other vital activities. Perhaps even worse, confusion about who makes which decisions and how they are made can increase the risk that some decisions will simply fall through the cracks entirely.4

Fortunately, getting decision rights “right” is well within the reach of any organization that is willing to give it enough attention and focus. That’s because getting it right depends largely on a surprisingly small set of factors. Our research shows that organizations with high organization design maturity characteristically:

- Simplify and clarify decision rights across the organization

- Establish strong, transparent accountability for decisions made

- Align individuals in decision-making groups to a common mission

- Encourage distributed authority

- Prioritize the customer voice in decisions

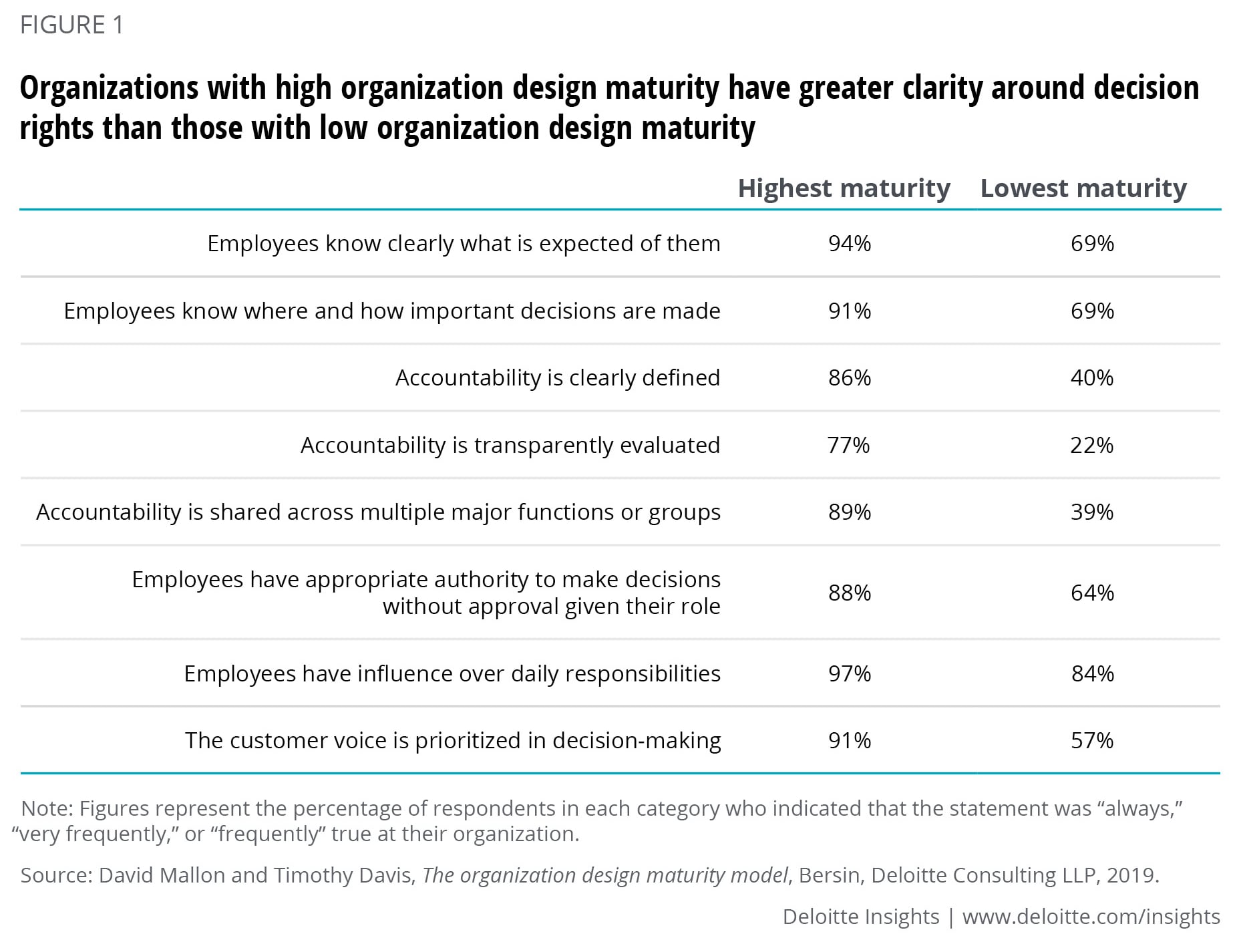

Together, these five attributes translate into a number of organizational attitudes and practices that support effective decision-making (figure 1). An organization that puts these attributes in place will be well-positioned to improve both the speed and quality of their decisions—with positive business results. The data supports this relationship: In 2016–2017, public companies in our data set that excelled in the five above areas increased their earnings per share (EPS) an average of 45 percent year over year, while organizations that performed poorly in the five areas averaged an 88 percent EPS decrease year over year.5

Decision rights 101

Before discussing the five attributes in more detail, it’s helpful to first explain exactly what “decision rights” means. At its most basic, “decision rights” refers to an organization’s rules and practices—whether explicit or implicit—around three questions:6

- Who are the individuals or groups empowered to make decisions? Decision rights models help outline an organization’s hierarchy of decision-makers or decision-making groups. When decisions must be made in groups, decision rights models specify which cross-functional leaders must belong to each decision-making body. (The term governance is often used to refer to decision rights related to cross-functional decision-making.)

- What decisions must be made? A decision inventory lists the decisions that an organization—that is to say, its leaders, teams, and operating units—must make. Note that a decision inventory does not need to be comprehensive to be useful. Rather, it should identify the organization’s most important decisions at various organizational levels—corporate management, business unit leaders, etc. While it may also be helpful to identify certain subsidiary decisions at each of those levels, many of these lower-order decisions can often be inferred from an understanding of the most important, top-level ones.

- How do operating processes and tools help support decision-making? A decision-making process defines the forums and procedures through which decision-makers across the organization make their decisions. Factors to consider here include how often a decision-making body should convene, what stakeholders decision-makers need to consult, and what evidence (such as data, research, or expert analysis or guidance) might be useful and available to inform these decisions.

Achieving clarity about the who, what, and how of decision-making doesn’t happen by accident, however. In our research, organizations with high organization design maturity were explicitly aware of the need to build decision rights into their organization’s designs. They deliberately set out to establish structures and procedures to enable decision-making empowerment, influence, and transparency, often prioritizing these elements even over defining the business’s daily workflows and functions.7

What’s so hard about decision rights?

If decision rights are so important, why do more organizations not sufficiently address them? Even many organizations that have recently gone through an organizational redesign effort, a restructuring, or a merger or acquisition—events where decision rights should have been explicitly considered—often struggle to articulate their decision-making accountabilities and processes. What makes decision rights such a common blind spot?

One probable reason is that few people recognize decision rights as a distinct organizational design need in its own right. We have found that many leaders tend to confuse decision rights with organizational structure, process, and workflow, mistakenly assuming that the design of roles or work processes will also adequately define the organization’s decision-making practices.8 Because of this, many organizations remain effectively stuck in neutral, with management viewing decision-making as a result rather than as something that needs to be actively—and proactively—addressed. The tacit assumption is that if an organization creates the right structures and processes, or reconfigures its organizational charts, then decision-making will happen naturally and automatically, and financial performance will improve. In reality, this is rarely—if ever—the case.9

The sheer size and complexity of some organizations can be another barrier. The bigger and more complicated the organization, the harder it can be to untangle existing decision-making practices and design better ones. Overlapping responsibilities can muddle the question of “who” makes decisions, resulting in inefficiency and slower responses to business opportunities. In fact, a major institutional challenge is often the tension between getting something done quickly versus collaborating, integrating, and bringing the whole company along—with “getting it done quickly” frequently taking priority. Fast decision-making is often celebrated, even when it’s not necessarily effective or well-informed.

A third, potentially even more pernicious reason that many organizations have difficulty addressing decision rights is resistance from senior executives. In some organizations, especially in traditional, more hierarchical organizations, executives may want the identity of the individuals making decisions to be obfuscated, particularly for top-level corporate decisions. Why? Because, in environments where decisions are made high up and out of sight, executives find they can more readily exert outsized influence behind the scenes. Leaders can make decisions based on personal interest instead of commonly understood evidence and analysis, and do so while avoiding clear accountability for the outcomes. Simply put, executives may resist explicitly defining the decision-making process because they fear diminishing their own power and influence.

Executive resistance to defining decision rights can be particularly strong in organizations where accountability is not already a strong part of the culture. In organizations where people do not believe that formal accountability can emerge from a defined process or venue, it can be difficult to hold anyone accountable for decisions, let alone senior leadership. In such organizations, top executives can often operate with impunity as they grow accustomed to exerting greater informal influence than they can formally.

More clearly establishing accountability for decisions, along with defining regular, transparent decision-making processes and forums, can indeed decrease executives’ informal influence. However, the payoff for doing this can be twofold. First, decision rights can become guardrails that prevent personal agendas and loyalties from superseding organizational goals. And second, better-defined decision rights and accountabilities can encourage greater collaboration by reducing the reasons for unhealthy competition between leaders and increasing their attachment to collective outcomes.

Five ways to get decision rights right

Let’s now return to the five attributes related to decision rights that characterize organizations with high organization design maturity. What does each attribute look like, and what can leaders do to help install them at their own organizations?

Simplify and clarify decision rights across the organization

At the risk of stating the obvious, the effectiveness of an organization’s decision rights practices depends critically on how clearly and simply those decision rights—the who, what, and how of decision-making—are defined and communicated. Our research shows that clarity in decision-making has the potential to double the likelihood of improving processes to maximize efficiency.10

One well-known tool that can be helpful in designating specific decision-making roles is the RACI framework, where “RACI” stands for Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed. In the context of decision rights, leaders can use the RACI framework to understand and agree on:

- Who is Responsible for executing the work? The responsible individual or individuals are those who carry out the actions prescribed by a decision—not necessarily those who make the decision.

- Who is Accountable for the decision’s outcomes? The accountable role identifies the actual decision-maker, whether an individual or a group. Optimally, each decision should have only one accountable role (that is, a single decision-making individual or group).

- Who should be Consulted for input, information, insights, and perspectives? Along with identifying the appropriate people to be consulted, a strong decision rights framework will also provide guidance on the consultative process (that is, how these consultations should take place).

- Who should be Informed about the decision and its outcome? These may include individuals in leadership positions as well as other decision-makers whose own decisions must take the prior decision into account.

In addition to simplifying and clarifying the who and how around decision-making, it’s also important to clearly articulate the what—which decisions are the highest priority. In many cases, understanding what decisions are most critical can help organizations better figure out the who and the how.

Simplicity and clarity in decision rights can sometimes prove to be the missing ingredient in an otherwise “stuck” transformation effort. For instance, one Fortune 500 organization in the financial services industry implemented several agile practices, including redesigning their organization into network-based teams, in an effort to become more agile as a business. However, leaders quickly found that the changed structure alone was not yielding the hoped-for benefits. They moved people and roles around and called them “chapters” and “guilds,” and yet nothing really changed; in fact, the new structure created further confusion and decision-making delays, as the accountabilities for decisions had not been clearly assigned. It was not until the organization focused specifically on decision-making that performance began to improve. Leaders clarified which few decisions mattered most—the ones that had a significant impact on resources and outcomes—and identified which person or group had the authority to make each decision. They then communicated these decision rights to the accountable people and groups, along with clear guidelines for when a decision would need to be escalated. By building transparency and accountability into decision-making, the organization increased worker satisfaction and significantly improved its ability to get products and services to market.

Establish strong, transparent accountability for decisions made

Just because an organization has done a RACI exercise to assign decision-making accountability doesn’t mean that those accountabilities have been made strong and transparent, which is the second key attribute of organizations with effective decision rights practices. To achieve strong, transparent accountability, leaders should consider and answer questions such as:

- Who is the primary owner of the decision’s outcomes?

- How—using what metrics—will these outcomes be evaluated?

- Where, when, and how will progress against these outcomes be evaluated?

- To what degree will the answers to these questions be shared openly and broadly within the organization?

The aim of strong, transparent accountability is not to assign blame for decisions gone wrong. Rather, transparent and clear accountability, complete with agreed-upon outcomes and metrics, makes it easier for an organization to review and reflect on past decisions and the process by which they were made, enabling the organization to better learn from both failures and successes. Focusing on decisions and outcomes, and not on individuals, reduces unhelpful anxieties and defensiveness and increases the potential for true reflection. The value of such transparency and reflection is backed up by research on organizational learning cultures: Organizations with greater clarity about both the identity of its decision-makers and the outcomes of the decisions made are better able to harvest invaluable wisdom from both success and failure, ultimately leading to better results.11

Decision-makers should understand, too, that it is not enough just to know where one’s own decision-making authority begins and ends. It can be even more critical to understand what roles others across the organization play in decision-making, including the specific decision-making accountabilities of key individuals and groups. This level of understanding is useful because it can help people identify and address decision-making bottlenecks and roadblocks. Most organizational decisions, after all, do not occur in a vacuum: Most have a critical path, with some having to be made before others can be considered, and knowing “where” (that is, with whom) the decision-making process is stuck is the first step in shaking it loose.

Align individuals in decision-making groups to a common mission

Sometimes, an organization may want certain decisions to be made by groups, not by individuals. One reason group decision-making can be desirable is that it brings multiple perspectives to the table, which can improve decision quality. The flip side, however, is that unhelpful competition and dissent within the decision-making group can slow the process and sabotage decision quality.

Establishing a clear common mission for the group can help counter this risk, allowing the group to reach decisions more quickly and less contentiously. To do this, the group should have a charter that articulates its mission, with the full endorsement of the organization’s senior leadership team. The organization should also establish individual and team incentives for the group that support the common mission.

As an example, at one global pharmaceutical company, decisions about resources and project prioritization had historically been made piecemeal, with the leaders of the R&D, marketing, legal, and compliance functions signing off on their “piece” of the decision, followed by the CEO reviewing and approving the decision—in this case, to move on to the next step in the drug development process—as a whole. This practice of pooling individual decisions for the CEO’s ultimate signoff was not only slow—many decisions were delayed as their individual components made their way up the chain of command—but also did not allow the functional leaders to take each other’s perspectives into account. To speed the decision-making process, the organization identified what decisions had to be made, determined which ones were most critical to the outcomes they cared about, and analyzed how these decisions were currently being made. They then assigned decision-making accountability to specific people or cross-functional groups, highlighting decisions for which they deemed it essential to bring cognitive diversity—diversity of thought—to foster innovation and get drugs to market more quickly. The common mission, communicated by the CEO as a strategic “must win” priority and reinforced through changes in bonuses and goals, was to speed up and improve the drug development process by making timely decisions in an integrated manner. Partly as a result of these changes, the company was able to accelerate its products’ time to market twofold.

Encourage distributed authority

Some important enterprise-level decisions must rest with C-suite executives or others in top management positions. But in the day-to-day course of business, these types of determinations are much less common than more routine decisions. Pushing such day-to-day decisions closer to where they directly affect operations—in effect, putting them in the hands of frontline workers—allows an organization to be more flexible and respond more quickly to changing marketplace needs.

That said, while giving frontline workers more decision-making authority can increase adaptability, it can also create confusion if accountabilities are not clearly defined and communicated. Just as with decision rights among management, it’s therefore important to explicitly articulate which frontline workers have the authority to make which decisions under what circumstances.

Empowering line workers to make decisions can pay off in greater agility and responsiveness. For example, the pharmaceutical company described above identified which decisions had to remain in the corporate center and pushed all remaining strategic investment and operational decisions to its frontline teams. Among other things, team leaders were empowered to make certain financial decisions within previously established budget guidelines, and given authority to change individuals’ performance measurement metrics and incentives. This, along with the shift to cross-functional decision-making, helped the company’s newest drug beat the previous time to market by two years and achieve a dominant position in the market.

Prioritize the customer voice in decisions

Among the most important ways to better understand customer wants and needs is for organizations to listen more closely to what their customers are saying. Indeed, our research finds the highest-performing adaptable organizations have learned to “put the customer and (the customer’s) outcomes at the center of every decision.”12 Giving customer-facing workers more decision-making authority is one way to increase the customer’s influence over these decisions.

In one instance, a famous consumer products company was setting up a new, flexible distribution center intended to tailor distribution to more effectively meet customer demand. To enable a more accurate understanding of customer demand and the ability to quickly act on this understanding, key decisions around how to bundle, ship, and deliver products were assigned to a cross-functional customer-facing team. This approach allowed the company to streamline these decisions to the extent that they can now adjust their tactics overnight to respond to immediate changes in customer requirements.

Decision rights as competitive advantage

Improving an organization’s decision rights practices is not always easy. Whether this work is initiated by the C-suite or elsewhere in the organization, getting decision rights right can mean fundamentally changing many things in the way the organization operates. Real and lasting change depends on engaging the right leaders and stakeholders, creating transparency throughout the process, and delegating decisions to the lowest organizational level possible to free top executives to manage institutional decisions.13 The effort will likely require people across the organization to change their behaviors and mindsets, and it will need to be supported by rewards systems and incentives to encourage change.

In the end, improving decision rights is an achievable goal that can start with the single decision to proceed. The benefits can far outweigh the investments. By adopting a detailed, well thought-out approach to decision rights, organizations can inspire a new culture of transparency and accountability that will help them become more competitive, more adaptive, and more responsive to marketplace needs.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the Human capital collection

-

Technologies that touch you Article5 years ago

-

Closing the employability skills gap Article5 years ago

-

Industry 4.0: At the intersection of readiness and responsibility Article5 years ago

-

Expected skills needs for the future of work Article5 years ago