Article

Achieving climate equity in Canada

Mobilizing the whole of government

Explore Content

- Climate change disproportionately affects marginalized communities

- Achieving climate equity will require an equitable transition toward net-zero

- Governments at various levels are well-positioned to meet the complexity and scale required to achieve climate equity…

- A whole-of-government response is best for advancing climate equity

- Canada has laid some of the foundations for establishing a whole-of-government response—now it’s time to commit to it

Climate change isn’t fair; it doesn’t affect everyone equitably. Both climate change and the actions taken to mitigate and adapt to it disproportionately affect marginalized communities. This report explores unjust climate impacts and how climate equity might be advanced in Canada through a whole-of-government approach. Serving as an introductory overview of climate equity, it focuses on the implications for governments and is the first of a series exploring what it will take to equitably transition to a net-zero society.

Climate equity is the principle that each individual—regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, income, and other characteristics—should benefit from a clean environment and have access to the resources and opportunities they need to protect themselves from the impacts of climate change.

Deloitte Insights –"Climate equity: Discovering the next frontier in outcome measurement in government"

Globally, low-income people and communities are more likely to be victims of severe climate events, while simultaneously being the most vulnerable to job insecurity resulting from the transition to a green economy.1 We know that, due to historical and current racial disparities, a higher proportion of low-income communities in Canada are made up of people of colour (POC).2 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (FNMI) Peoples in particular experience discrimination and violations of their inherent ancestral and treaty rights. These same groups are also less likely to be included in government decision-making.

Canadian political leaders have shown interest in gaining a deeper understanding of the intersection of inequality and climate change, as demonstrated by the push for the first national adaptation strategy, the strengthening of the Environmental Protection Act, and proposed legislation to address environmental racism. We believe that only such a whole-of-government approach will allow Canada to achieve climate equity domestically and support progress abroad.

Climate change disproportionately affects marginalized communities

When faced with a climate event, marginalized, low-income people are often less able to adapt due to limited financial capital. Unlike people with higher incomes, marginalized populations may struggle to rebuild after climate catastrophes. Relocation can bring economic and spiritual burdens, especially for Indigenous Peoples who are deeply connected to the land. These outcomes can increase the risk of physical and mental health challenges.

The same communities bear a disproportionate burden of pollution too, especially air pollution, which causes up to seven million deaths per year globally.3,4 In Canada, that means an estimated 10,000 deaths every year.5 Research from the United States, taken over three decades, shows that industries target low-income and racialized communities for hazardous waste sites.6 This discrimination, often referred to as environmental racism, exacerbates other inequities, such as poverty, lack of access to health care, food insecurity, and unemployment. Eradicating environmental racism will be an essential step toward achieving climate equity.

Environmental racism refers to environmental policies, practices, or directives, that disproportionately disadvantage individuals, groups, or communities, (intentionally or unintentionally) based on race or colour.

-Canadian Commission for UNESCO (July 2020) – Environmental Racism in Canada

From coast to coast to coast, FNMI and POC communities have suffered from environmental racism. In 2006, for example, a landfill was reopened in Lincolnville, Nova Scotia, despite decades of opposition from the local African Nova Scotian community concerned about hazardous materials causing high rates of cancer, asthma, and other illnesses, economic fallout that had not been appropriately compensated, the reduction of well-being due to foul smells, and the increase in dangerous wildlife like bears, raccoons, and insects.7 In Ontario, meanwhile, the Aamjiwnaang First Nations community on the south side of Sarnia is located in a cluster of more than 50 petroleum refineries, petrochemical plants, and energy facilities in Canada’s aptly named “Chemical Valley,” where the cancer-causing chemical benzene has been forecast at up to 44 times the ambient air quality criteria.8

It’s not all bad news: small wins show the potential for change

Some localized legal efforts to combat or repair the effects of environmental racism have started to take root. The Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishinabek First Nation (formerly known as Grassy Narrows First Nation) successfully secured $85 million from the Government of Ontario to clean up the industrial mercury that was poisoning their community near Kenora, Ontario.9 In Nunavut, the Clyde River Inuit took Petroleum Geo‑Services Incorporated to the Supreme Court, arguing that they were not adequately consulted prior to the approval of the company’s five-year oil exploration project that would use seismic blasting in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait—and they won.10

Similarly, the Tataskweyak Cree, Curve Lake, and Neskantaga First Nations settled a class-action lawsuit against the federal government for failing to uphold sections 7 and 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, securing $1.5 billion for the affected individuals and $3 billion to increase access to clean water.11 Although these wins were important first steps and may set precedents for other climate equity issues, their reach is limited; environmental discrimination continues across the country. The Neskantaga First Nation remains on a nearly three-decade boil-water advisory, longer than any other First Nation, clearly demonstrating that accountability is an ongoing struggle.12

Achieving climate equity will require an equitable transition toward net-zero

One mechanism for attaining climate equity is the facilitation of an equitable transition from carbon-intensive economic activities toward a net-zero society. The term “equitable transition” is often used interchangeably with “just transition”; however, for the purposes of this report, we use “equitable transition” throughout, except when directly quoting or referencing legislation. Traditionally, the concept has been focused on the workforce in the transition to a low-carbon future.13 A 2022 Deloitte report highlighted how a coordinated and rapid journey toward net-zero is set to deliver more than 200 million new jobs globally by 2050. It will also displace workers and communities that exist around carbon-intensive activities, so it is the responsibility of policymakers to ensure those who stand to lose the most from it are supported and protected.

The workforce is as complex as the humans that make it up. This complexity, combined with the unrelenting pace of economic change, sees the structure of the workforce create gaps between the types of jobs that are created and the types of workers and skills an economy has to fill them.

Deloitte, Work toward net-zero: The rise of the Green Collar workforce in a just transition

Today, we understand that an equitable transition is inextricably linked to climate equity, and goes beyond workforce modernization to include social empowerment, community resilience, economic diversification, environmental equity, and First Nations, Métis, and Inuit sovereignty and leadership. We also acknowledge the complexity governments face in establishing FNMI economic equity throughout and the need to ensure the path to economic nation-building is not adversely affected and to fulfill the duty to consult under section 35 of the 1982 Constitution Act.

While environmental racism focuses on more marginalized people, there are other populations also disproportionately impacted by climate change. As noted above, The workforce is as complex as the humans that make it up. Canada’s federal government has been thinking about how to implement an equitable transition for the workforce since 2018, when it established a task force to examine fairness in the phasing out of coal-fired electricity.14 This task force made 10 recommendations for how to support Canadian coal workers and communities. Recently, the Minister of Natural Resources promised just transition legislation before the end of 2023.15 It will be an important step for driving climate equity forward, since these transition efforts are inherently tied to equity objectives, but again, equitable transition efforts must go beyond workforce transition to include deeper representation of the issues affecting other marginalized communities.

In addition, the underrepresentation of women and gender-diverse people in political, climate, and corporate decision-making leads to policies and practices that do not consider their needs, aggravating the inequitable effects of climate change. To realize their commitments to gender equity, governments must reform existing programs and develop new initiatives to ensure women and gender-diverse people have access to supports that are culturally appropriate and relevant to their specific needs.

Achieving climate equity is a complex objective because it cuts across many spheres of life (social, economic, political, health, education, etc.), will involve many actors (businesses, community groups, individuals, and all levels of government), and will take significant investments of both time and resources. A more comprehensive approach to climate equity will be essential to make meaningful progress.

Governments at various levels are well-positioned to meet the complexity and scale required to achieve climate equity…

Governments provide collective goods and services that Canadians cherish, such as education and health systems, pensions, and infrastructure. Canada’s federalist political system establishes a division of responsibilities between local governments, provincial and territorial governments, and the federal government, a design that requires cooperation and gives more attention to regional and local issues than unitary states with a single, centralized government. Although divisions between municipalities and/or regions can sometimes be a roadblock to action, the promotion of collaborative federalism through well-functioning and good-faith intergovernmental relations can create what political scientists call the “positive policy feedback,” whereby supporters of intergovernmental efforts work to sustain policies with positive feedback and transform the mindsets of other relevant stakeholders, including the public.16

Across Canada, governments have broad networks of partners that can tap into a wide ecosystem of stakeholders with the required expertise, resources, and influence to enable the broad systemic changes required to achieve climate equity. Because FNMI leaders have been, and continue to be, at the forefront of climate action across the country, they are especially well-suited to partner with the private sector and various levels of government, and to leverage meaningful partnerships with affected communities. Indigenous-led climate solutions empower communities and drive a more equitable approach to establishing a sustainable economy. Indigenizing approaches to climate action also accelerates progress toward reconciliation.

Whereas the private sector can spur innovation and scale solutions, governments can address climate inequity by taking a longer-term view, driving change that reverberates across decades rather than by the quarter. All levels of government can leverage policies and regulations to make system-wide changes that will have important ripple effects across geographies, industries, groups, and time.

… but challenges are stalling progress

Canada is a vast land with a diverse population, and our political system reflects these and other complexities. The role and scope of the climate response is broad, with a multitude of overlapping institutions. Tackling an issue as complicated as climate equity will require integrated solutions in which all overlapping considerations are addressed in context of one another.

Climate equity and the housing crisis: complexity at work

There’s ample evidence that low-income urban neighbourhoods, which tend to have higher populations of FNMI, POC, and newcomers, suffer more than others from extreme heat.17 This is largely a result of poor urban planning: such neighbourhoods have a higher population density and less vegetation. The results are unsettling—for example, people living in them are at greater risk of premature births.18

There’s no simple solution to the housing crisis. Municipal and provincial governments cannot easily move or rebuild homes and communities. And some solutions may inadvertently create more greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Building more affordable housing also comes with challenges. Urban sprawl has negative impacts on the environment, especially when policymakers infringe on delicate ecosystems and greenbelts.19 Similarly, building affordable housing in areas poorly connected by public transit may drive carbon emissions higher by requiring the use of private vehicles. It’s essential that all the tools available be used to generate solutions to these highly complex issues—and that means planning and coordination across all levels of government.

It’s clear that climate equity must be integrated into wider climate priorities. The world is working to keep the increase in global average temperatures below 1.5°C (above pre-industrial levels), and Canada has made a series of commitments to do its fair share to achieve this, including reducing GHG emissions by at least 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050.20 Unfortunately, multiple climate trackers and watchdogs have given Canada poor ratings on progress toward these goals, and mounting political pressure is creating a greater sense of urgency, leaving less room for other important climate considerations such as ensuring equity.21

Canada is also seeing declining public trust in all levels of government, meaning citizens are less likely to support government direction, which makes widespread consensus and collaborative action more difficult.22 Better implementation of consistent, coherent, and effective climate policies can help to address this lack of trust.

A whole-of-government response is best for advancing climate equity

To take the actions necessary to mitigate and adapt to the changing climate, an integrated, whole-of-government approach is needed. First, governments must find the connections within their own institutions between their own policies and delivery levers. There must also be a cohesive approach between the different levels of government, with strong efforts made to integrate objectives, policies, and approaches across all jurisdictions and mandates.

A whole-of-government approach is a comprehensive way to assemble resources and expertise from multiple agencies and groups to address problems with interrelated social, economic, and political causes. The approach plays to comparative advantage and maximizes resources.”

Deloitte Center for Government Insights, Deploying the whole of government: How to structure successful multi-agency international programs23

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is the department responsible for national climate action and each of the provinces/territories has its own ministry or department that deals with climate change. Ultimately, the provinces and territories hold significant power in making environmental decisions, having primary jurisdiction over their natural resources. They and other levels of government in Canada currently approach emission goal-setting, tracking, and reporting differently, making a cohesive plan difficult. A joint report from auditors general across the country reported that “seven provinces and territories did not have an overall target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2020” and that there was “limited coordination” on climate action between federal, provincial, and territorial governments.24

Although ECCC is responsible for coordinating action at the federal level, climate equity involves a complex set of issues that overlap across most federal ministries. These ministries must execute their unique contributions to climate equity while working together to address multi-faceted challenges. Achieving climate equity also requires all levels of government to work with other coordinating structures (such as cabinet committees, standard-setting organizations, policy implementers, and the judicial system) and with civil society to create a system that is consistently working toward this goal, while also protecting marginalized communities and improving reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and Canada.

As our understanding of the complex effects of climate change grows, the need to include more ministries, agencies, and other administrative bodies in the plans to mitigate the impacts becomes clearer. Several advisory bodies and public-facing groups promote inter-ministerial cooperation, such as the Net-Zero Advisory Body, the Cabinet Committee on Economy, Inclusion and Climate, and the Privy Council Office’s Climate Secretariat. Ensuring these bodies are empowered to facilitate cooperation between and within governments continues to be essential.

If activities across governments happen in a siloed manner, it will result in, at best, inconsistent or stalled progress. At worst, there could be contradictory climate action, leading to an inability to meet climate goals, deeper mistrust, and greater inequities, especially if the federal government fails to work with the provincial/territorial governments on mutually agreed-upon outcomes. Departments and agencies will not only require strong and consistent direction, but also more financial and political support to enable effective action to reach climate equity.

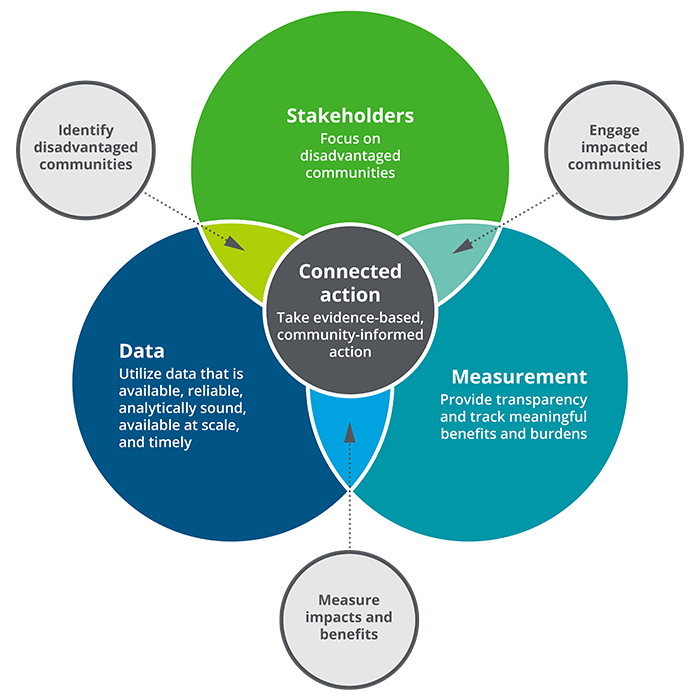

Three key elements are essential to enabling the large-scale, connected action needed for a whole-of-government approach: engagement with the most impacted rightsholders and stakeholders; robust data collection; and transparent measurement and reporting (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

A framework for connected action

Source: Deloitte analysis, Deloitte Insights, deloitte.com/insights

It’s important to note that FNMI Peoples have not endorsed the colonial structures of the Canadian government. Many FNMI nations are sovereign bodies with self-governance structures, even where these governance structures are not federally recognized. Since 1975, the Canadian government’s policy has been gradually advancing to recognize FNMI sovereignty through modern treaties and self-government agreements, such as section 34 of the 1982 Constitution Act (the Charter of Rights and Freedoms), which provides protection of treaty rights. However, much work remains to be done on the journey toward reconciliation. The importance of recognizing FNMI leadership structures as partners in climate action in a whole-of-government approach cannot be overstated.

A renewed approach to stakeholder engagement

To address climate injustice, the distinct experiences of communities that are historically and currently marginalized need to be better understood, including the barriers they face in accessing employment, education, health care, and social inclusion. There also needs to be recognition of how these experiences may result in apprehension or resistance in engaging with the government.

The ways governments interact with communities will continue to evolve as new tools become available and as the sharing of data becomes more common among stakeholders. Advanced analytics increases governments’ ability to collect, visualize, and understand data. Modern tools should be leveraged to empower early, open, and continual consultations with the public, especially the groups that stand to lose the most from the climate transition. Feedback from such community engagement efforts should be used in the development of formalized mechanisms that establish inclusion throughout the decision-making process.

Canada has laid some of the foundations for establishing a whole-of-government response—now it’s time to commit to it

Canada has finally recognized the right to a healthy environment for the first time in federal law.25 The implementation of this right will account for the principle of environmental justice, ensuring environmental harms do not disproportionately impact marginalized groups. This significantly builds on the federal government’s Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy plan, which aims to integrate “climate considerations throughout government decision-making.”26

While the plan covers many topics related to climate equity, it’s not comprehensive in addressing the ways climate equity intersects with the various levels of government. A more systematic and thorough detailing of how the federal government plans to contribute to and maintain intergovernmental alignment, combined with a more comprehensive integration of climate equity as a central principle, is needed. Moreover, the name of the plan itself reflects the intent when the promotion of climate equity should be about the well-being of all Canadians, including but not limited to economic well-being. The recent recognition of the right to a healthy environment and the corresponding implementation framework presents an opportunity to centre climate equity and develop plans for a whole-of-government response.

In 2022, the federal government released the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan, which pulled together input from the provincial/territorial governments, Indigenous communities, and the public to create a sector-by-sector path to reach its emissions reduction targets.27 It’s a good example of using a whole-of-government approach. Unfortunately, the plan is light on equity principles. Later in 2022, the first National Adaption Strategy and Action Plan was released, an attempt by the federal government to prepare for and respond to the effects of climate change by outlining long-term goals in five key areas: disaster resilience, health and well-being, nature and biodiversity, economy and workers, and resilient infrastructure.28 While all these areas have substantial impacts on climate equity, in-depth analysis conducted by the Canadian Climate Institute identified some serious deficiencies in the plan, such as inadequate funding to achieve goals and the absence of new approaches to improve policy coordination across government agencies.29

Parliament has been making efforts to address a crucial element of climate equity through a private member’s bill, Bill C-226, which would compel the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to create a national strategy within two years to tackle environmental racism.30 If passed, this bill may encourage the amendment or reform of other legal structures, such as zoning laws that dictate land use (often leading to situations of inequity), the enforcement of environmental protections and anti-discrimination legislation, the removal of legal barriers for environmental grievances, and the centring of FNMI environmental leadership. In conjunction with the newly recognized right to a healthy environment, these actions would represent positive momentum toward creating the legislative environment necessary for accelerated climate equity.

To continue building momentum toward climate equity, we have five recommendations:

- The federal government should adopt a whole-of-government approach, implementing a mandatory climate equity lens with clear and ambitious objectives for all relevant departments. An intergovernmental task force could work to integrate the climate actions of provincial/territorial and municipal governments across their jurisdictions, tailored to the specific needs of their communities. This could be done by strengthening the Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy plan, including a more comprehensive integration of climate equity principles.

- The federal government should recognize FNMI leadership structures as leading partners and establish government-Indigenous climate equity working groups that inform climate decision-making processes. Indigenous-led environmental assessments should be recognized as a best practice.

- The whole-of-government approach should have an integrated community engagement mechanism that prioritizes disadvantaged communities—especially racialized and low-income groups that have been historically marginalized—and that ensures participatory decision-making for climate equity issues.

- All levels of government should establish consistent and reliable climate equity funding, mobilized through existing climate funding mechanisms to reduce duplication and administrative costs. Equity principles should be integrated into all climate projects that receive government funding.

- The federal government should convene stakeholders across the public and private sectors to design appropriate data-gathering and data-sharing mechanisms that are inclusive of the data and methods in FNMI, POC, and other marginalized communities (and leverage other standard data sources, such as the census) to collect information on environmental racism and other climate equity issues. The whole-of-government approach should remain flexible as more information becomes available. All data should be included in timely, clear, transparent, and continual reporting to the public about progress.

Conclusion

Climate change is not neutral—populations are impacted disproportionately along social and economic fault lines. Any response to climate change must consider climate equity to prevent marginalizing people further.

This report provided an introductory overview of the concept of climate equity, emphasizing the comprehensive response that will be needed as Canada attempts to address climate change. We believe achieving climate equity will require the full force of all levels of government in a whole-of-government approach as the country strives with the rest of the world to transition to a low-carbon future.

Endnotes

Explore Content

- Climate change disproportionately affects marginalized communities

- Achieving climate equity will require an equitable transition toward net-zero

- Governments at various levels are well-positioned to meet the complexity and scale required to achieve climate equity…

- A whole-of-government response is best for advancing climate equity

- Canada has laid some of the foundations for establishing a whole-of-government response—now it’s time to commit to it

Recommendations

Equitable transition in Canada

Climate change does not affect all of us equally

Sustainability and climate | Deloitte Canada

Learn how we could create a more resilient and sustainable future for your organization and the environment.