Learning in the flow of life 2019 Global Human Capital Trends

8 minute read

11 April 2019

In a competitive external talent market, learning is vital to an organization’s ability to obtain needed skills. But to achieve the goal of lifelong learning, it must be embedded into not only the flow of work but the flow of life.

Learning is the top-rated challenge among 2019’s Global Human Capital Trends. People now rate the “opportunity to learn” as among their top reasons for taking a job,1 and business leaders know that changes in technology, longevity, work practices, and business models have created a tremendous demand for continuous, lifelong development. Leading organizations are taking steps to deliver learning to their people in a more personal way, integrating work and learning more tightly with each other, extending ownership for learning beyond the HR organization, and looking for ways to bring solutions we use in our daily lives into the learning environment at work.

Learn more

Watch the related company story videos for this trend: Kraft Heinz, Team4Tech, Unilever

View 2019 Global Human Capital Trends

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Download the full report or create a custom PDF

Deloitte’s 10th annual Global Human Capital Trends Report is coming soon. Get it first by signing up!

Our top-rated trend for 2019 is the need to improve learning and development (L&D). Eighty-six percent of respondents to our global survey rated this issue important or very important, with only 10 percent of respondents feeling “very ready” to address it. Why are we seeing such high levels of concern?

Evolving work demands and skills requirements are one big reason. Our conversations with business leaders reveal that they, as well as workers themselves, are worried about how technologies such as robotics and AI could change jobs and how people should prepare to do them. Their concern is warranted: While some jobs are disappearing due to technology—38 percent of our survey respondents expect to eliminate certain jobs due to automation over the next three years—many more are being transformed. In fact, the most significant workforce and talent issue for C-suite executives that our respondents identified this year was “transitioning to the future of work” (28 percent), followed by the need to redesign work (25 percent) and reskill the workforce (24 percent). Moreover, 90 percent of our survey respondents told us their organizations are redesigning jobs, and 32 percent are doing it substantially. Given that many jobs are changing, it may come as no surprise that, according to a recent World Economic Forum report, more than half (54 percent) of all employees will require significant reskilling and upskilling in just three years.2

Reskilling has become a growth imperative for organizations, many of which have seen positions go unfilled for months or years for lack of the right talent to fill them. It’s become increasingly apparent that organizations in today’s tight talent market cannot depend solely on recruitment to find people for those roles. Low unemployment rates and tight labor markets for skilled workers in many countries have made it difficult to hire “ready-made” workers in a timely manner (it takes an average of 42 days to fill an open job today).3

Our survey respondents appear well aware of the major role learning must play in obtaining badly needed skills. When we asked them how they will deal with issues of job redesign, more leaned toward training than toward hiring as a way to obtain the talent they need (figure 1). Eighty-four percent also said that they were increasing their investment in reskilling programs, with 53 percent saying that they would increase this budget by 6 percent or more. And 77 percent of organizations are increasing their learning team’s head count, elevating learning to the second-fastest-growing role in HR.4

But despite the efforts and investments being made, our survey results suggest that L&D teams are not moving the needle far enough. Yes, many L&D groups are taking positive steps such as adopting agile and self-directed learning models, acquiring new libraries of content, and moving L&D closer to the business. But while 50 percent of our respondents reported that their L&D departments were evolving quickly, 14 percent said that this evolution was not happening fast enough. And with regard to learning culture, only 11 percent of our respondents—one in nine—said that it was “excellent,” with a further 43 percent rating it as good. The call to action is clear: Organizations must work to instill an end-to-end cultural focus on learning, from the top of the organization to its bottom, if they want to meet the talent challenges that lie ahead.

Learning and work: The new organizational ecosystem

Rapid and ongoing changes in the nature of work itself are changing the relationship between learning and work, making them more integrated and connected than ever before. This creates a challenge and an opportunity to build robust work-centered learning programs, helping people consume information and upgrade their skills in the natural course of their day-to-day jobs.

To help accomplish this, we believe a new model may emerge which takes inspiration from the evolution in information technology development we have seen in recent years. As the pace of technological change has increased, IT teams have evolved from sequential, “waterfall” design-develop-test-operate models to new agile models, sometimes known as “DevOps,” that integrate system design, development, security, testing, and operations into a team-based, connected process. In similar fashion, we anticipate new approaches to integrating learning and work to arise, perhaps combining development and work into “devwork”—building on the realization that learning and work are two constantly connected sides of every job.

To help enable the creation of this “devwork” environment, we anticipate that business and HR leaders will need to:

- Seek out opportunities to integrate real-time learning and knowledge management into the workflow. With cloud-connected mobile and wearable devices becoming almost omnipresent, and the introduction of augmented reality devices, organizations will be able to explore new approaches to virtual learning in which learning occurs in small doses, almost invisibly, throughout the workday.

- Make learning more personal so that it is targeted to the individual and delivered at convenient times and modes so that people can learn on their own time. Here, technology can play an important role. With growing numbers of learning providers now offering video, text, and program-based curricula in smaller, more digestible formats, organizations have an opportunity to craft approaches that allow their workers to learn as and when they see fit.

- Integrate learning with the work of teams as well as individuals. As teams become more important in the delivery of more types of work, organizations will offer learning opportunities that support individuals as members of teams, providing content and experiences specific to the context of a worker’s team.

Joint ownership, joint accountability

Just as “DevOps” combined software development and IT operations, “devwork” must also look to shared ownership to enable success. There is a growing view, reflected in our survey, that the responsibility for learning and development should be coowned: between workers and their organizations, between HR and the business, and among organizations, educational institutions, and governments. In our survey, 38 percent of respondents said they felt that L&D and the business should share responsibility for learning; of those who said that learning at their organization was not currently positioned for success, 48 percent said that it should move to being a shared responsibility between L&D and the business.

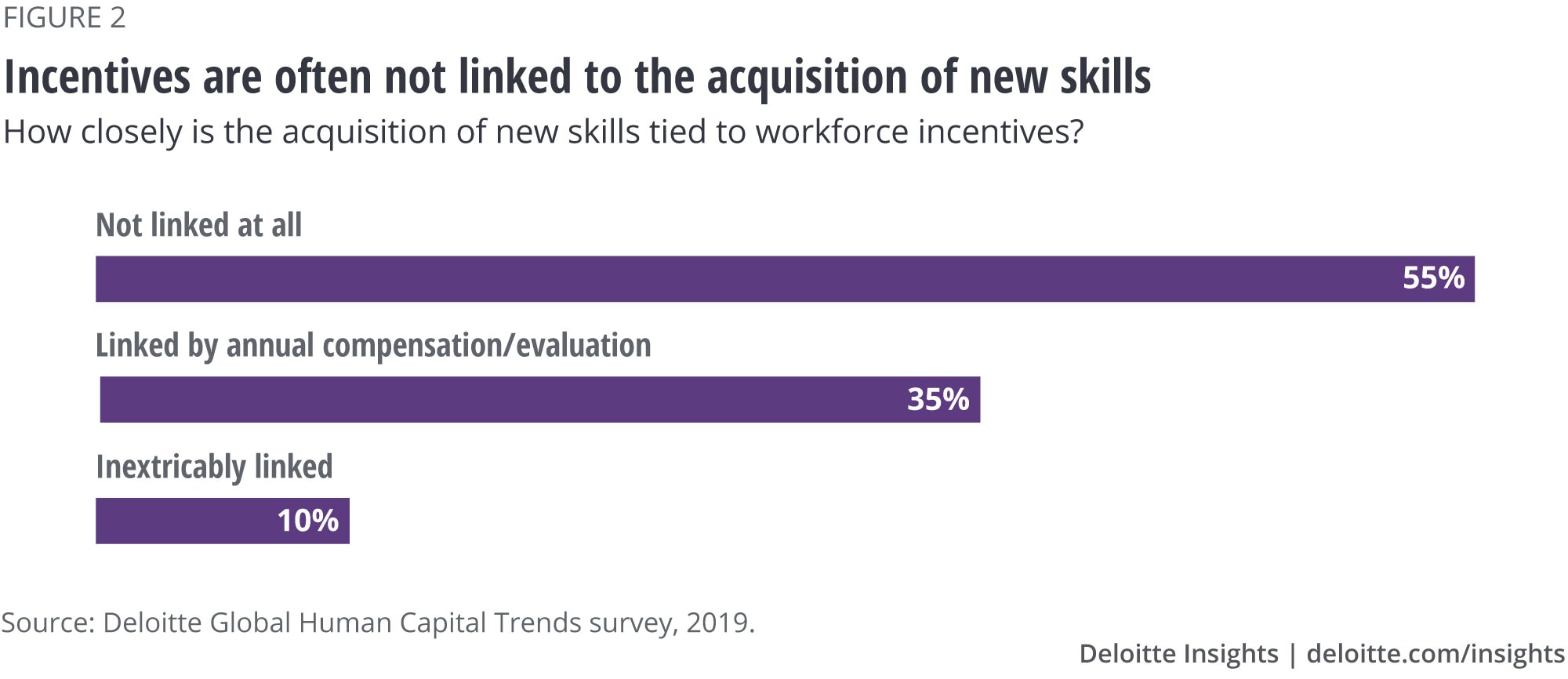

This shared responsibility does more than create joint ownership; it enables joint accountability for success—an area that our survey suggests remains a significant gap in most organizations. Despite often major investments in learning, many organizations are not linking performance incentives to their learning programs, increasing the risk that their learning investments may go unused and unappreciated. It is sobering in this regard that 55 percent of this year’s survey respondents said that incentives were “not linked at all” to the acquisition of new skills (figure 2), suggesting that ample opportunity exists to create and strengthen this connection. Organizations that put incentives in place to help make sure that managers support learning, and that employees find learning opportunities practical to pursue, are likely to reap benefits both in terms of new skills learned and in terms of encouraging a learning culture.

Recoding learning into the flow of life

Integrating learning and work may not be the last challenge that organizations—and individuals—face. Consider that one in four workers in the United States will be 55 or older by 2024.5 (To put this in context, in 1994, workers over age 55 accounted for only about one in 10 workers.6) Business and talent leaders, not to mention workers themselves, now need—for the first time—to plan for careers that can span 50–60 years out of a potential 100-year life.7 Longer life expectancies, combined with frequent job changes and the accelerating rate of skills obsolescence, call for significantly new approaches to creating diverse portfolios of learning and work experiences to support people who may work in many different fields and disciplines during their working lives. The challenge may be nothing less than to integrate ongoing learning into the flow of life.

If that is the challenge, then the solution must not only be embedded into the ways in which we work, but the ways in which we live. Enter the emergence of learning experience platforms (LXPs), the latest and possibly most pervasive trend in the area of learning technology. LXPs represent a much-needed evolution from today’s traditional learning management systems (LMSs). Where LMSs have historically been focused on business rules, compliance, and catalog management, LXPs are true content delivery systems whose functionality mirrors common technologies people use in their day-to-day lives such as streaming video and social media.8 With LXPs, content can be integrated into any system to offer on-demand learning; material can be organized into channels or playlists based on specific topics, skills, or learning objectives; and users can share and rate content, leave comments, and receive recommendations using dynamic social settings.9 In this way, the LXP becomes not just a tool for how people learn at work, but a solution for how people learn in life.

In a world where technology is changing jobs and people are living longer lives with more diverse careers, organizations have not only an opportunity, but a responsibility, to reinvent learning so that it integrates into the flow of work—and life. In the age of the social enterprise, organizations will realize that creating and maintaining a culture of lifelong learning is not just part of their mission and purpose, but is what gives their workers meaning both in and out of the workplace. And nothing is more personal than that.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

Accessing talent Article6 years ago

-

Talent mobility Article6 years ago

-

Rewards Article6 years ago

-

HR cloud Article6 years ago

-

Looking ahead Article6 years ago

-

2019 Global Human Capital Trends Collection