Midstream: Charting a new course amid market dynamism Decoding the O&G downturn

8 minute read

23 April 2019

The midstream sector is crucial for the oil and gas industry’s success, but much has changed with the entry of shales and altered trade flows and routes. How can the sector thrive amid this uncertainty?

The midstream segment is not only a key element in the O&G industry’s biggest supply story but also appealing to many energy-focused investors for its consistent free cash flow generation in the past. However, the segment, despite its critical role and stable fee-based business model, has struggled to create additional wealth for its shareholders during the downturn as well as the recent upturn in 2017–18. The short-cycled production profile of shale resources and altered trade flows and routes have brought new challenges to this segment, keeping it under pressure. How have various sub-segments in the midstream segment responded to this complex business environment?

Although many industry pundits have provided piecemeal perspectives across the phases of the downturn and recovery, a consolidated analysis of the past five years and a complete perspective covering the entire O&G value chain could help stakeholders—from executive to investor—make informed decisions for the uncertain future.

With this in mind, Deloitte analyzed 843 listed O&G companies worldwide with a revenue of more than US$50 million across the four O&G segments (upstream, oilfield services, midstream, and refining & marketing) in an effort to gain both a deeper and broader understanding of the industry. The ensuing research yielded a six-part series, Decoding the O&G downturn, which sets out to provide a big-picture reflection of the downturn and share our perspectives for consideration on the future.

In part four of the series, we explore the state of the midstream segment—assessing its overall health, identifying possible reasons behind its flat performance, analyzing its investment profile, and comprehending the importance of revamping commercial and capital arrangements in this volatile market environment.

Learn more

Create custom PDF or download the full report

Read all articles in the series—Decoding the O&G downturn

Browse the Oil, Gas & Chemicals collection

Read an article featuring these insights from Rigzone

Read an interview with Deloitte’s Andrew Slaughter

Read an article on this report from Oil & Gas Journal

Subscribe to receive related content

Investors proceed with caution

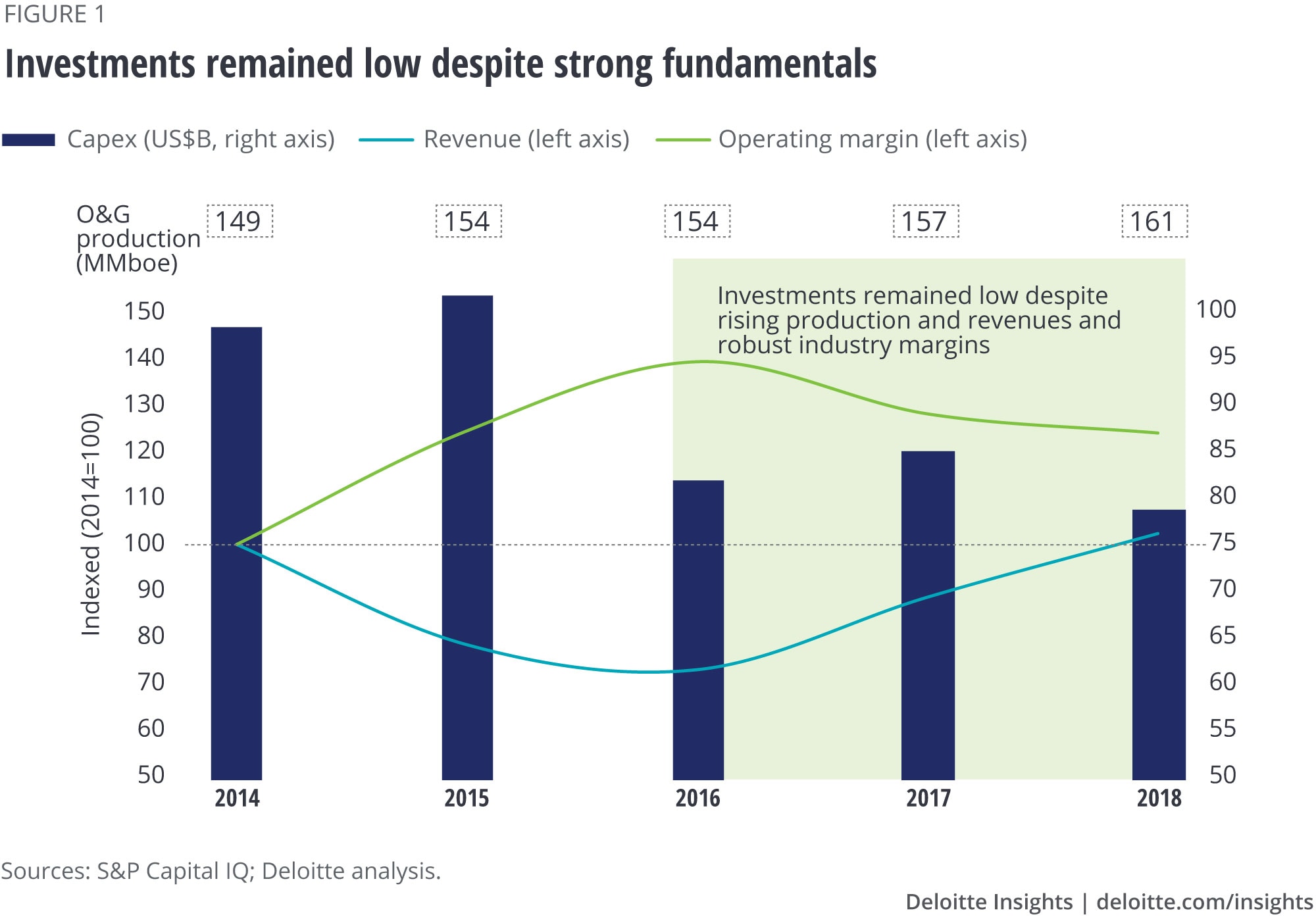

A supply boom and strong demand for both crude oil and natural gas have enabled a highly advantaged business environment for midstream companies worldwide. Global O&G supply grew by 11 percent, while demand expanded by 8.5 percent over the past five years.1 Robust volume expansion (especially emergence of LNG and the coming of new supply centers) and a stable fee-based business, as expected, explain the strong growth in both top and bottom lines of midstream companies worldwide (figure 1). In fact, the companies paid dividends to the tune of US$19 billion while keeping their leverage ratio flat at 51.5 percent.2

However, the picture is quite different on the investment and value creation front. The midstream sector has remained cautious even as upstream players expect future growth. This seems clear from falling midstream investments—midstream capex CAGR across all regions has remained in the range of -7 to -11 percent during the past four years.3 And while investors have acknowledged the discipline exhibited by companies, they expect a much faster pace of infrastructure growth to absorb growing supplies and meet latent demand—the market capitalization of global midstream companies in 2018 was 4 percent lower than in 2014.4

Unlike in other O&G segments and industries, investors in midstream typically use the common lens of a yield-focused mindset to evaluate the segment across the globe. However, changed supply conditions on the upstream side and varying infrastructure needs and regulations of countries could require a deeper assessment by regions and a more differentiated view by investors. While the US midstream sector seems to find it challenging to manage capital cycles in a more dynamic shale world, non-US companies are facing issues that are unique to the part of the value chain they operate in. And given the criticality of midstream infrastructure, even short-term uncertainty in resolving these challenges could pose risks to future O&G volume growth.

US midstream: Both reactive and proactive strategies fail to deliver

After the oil downturn started in mid-2014, midstream companies, skeptical of the sustainability of then high-cost US shale production, broke the linear relationship with upstream investments and slashed their capital programs. Despite realizing that they were risking their future growth, most midstream companies reduced their investments seeing rising cost of capital, falling returns, and high distribution commitments. But then, shale companies surprised them by delivering phenomenal volume growth even in a low-price environment. However, because of the time taken to build pipeline infrastructure, midstream companies could not catch up. The result: Many midstream companies lost notable volume growth potential as capacity bottlenecks pushed E&Ps to either delay completions or explore other transportation options.

Realizing that being reactive was not working, most midstream players then followed a proactive approach and increased their spend on infrastructure development by 25 percent in 2017 despite their high cost of capital: ROC (return on capital)–WACC (weighted average cost of capital) spread averaged around -1 percent when midstream investments went up in 2017.5 Further, visible shale volume growth appeared to entice them to maintain their high capex in 2018 as well (figure 2). But this growth came with a high cost of capital, and thus lower margins.

With oil prices falling and volatility returning in late 2018, now, there is a risk of supply growing less than anticipated or planned for. Although shale production has consistently surprised to the upside, some estimates caution against possible pipeline overcapacity of 15–40 percent over the next five years in some shale plays.6 This could explain the underperformance of US midstream companies, where both reactive and proactive investment strategies have failed to deliver in a highly dynamic shale environment.

One may rightly argue that midstream investments self-balance over a period of time, and the lag or lead in infrastructure growth is intrinsic to this business. But shale’s dynamism and intensifying competition likely require a much closer alignment of upstream growth and infrastructure planning in the United States.

Non-US midstream: Bound by regional differences

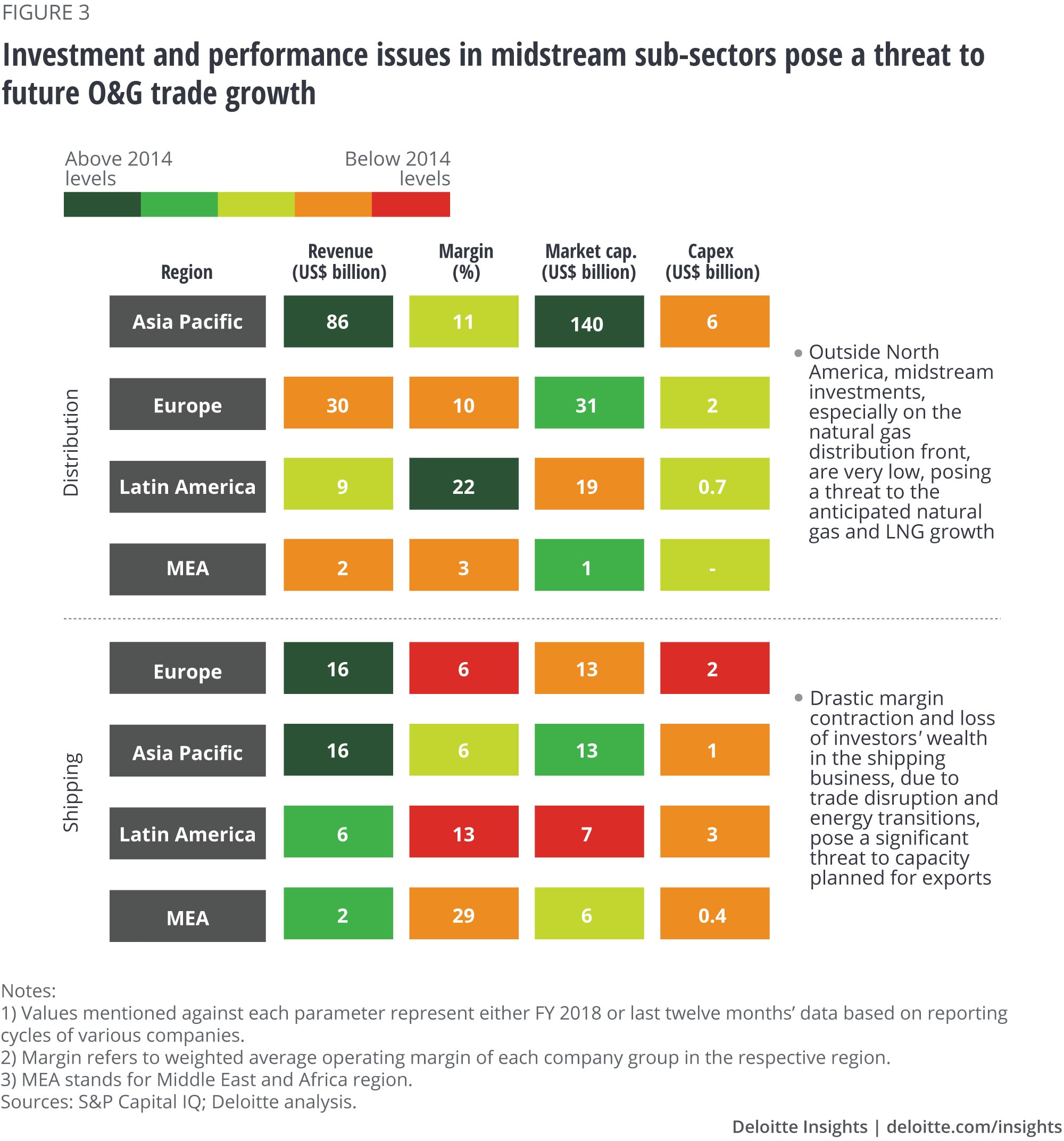

Global growth in natural gas as a fuel for the future and altered trade flows due to the shale boom have had a profound impact on international midstream companies. While Asian gas distributors seemed highly cautious about the projected “high” gas demand growth in the region, the shipping industry seems to have struggled to align with changing trade patterns and geopolitical uncertainties (figure 3).

Gas distribution: Growing strong, yet failing on last-mile connectivity

Gas distribution companies, especially in Asia-Pacific (APAC), witnessed one of the best performance periods as low commodity prices, and growing supply of LNG from Australia and the US helped them capitalize on old infrastructure investments. Revenue and market capitalization for these companies reached an all-time high of US$86 billion and US$139 billion, respectively.7

However, from a sector that is expected to be the backbone of future LNG growth in the region, one might also expect a solid growth plan apart from good financial performance. Instead, investments to expand the APAC distribution infrastructure reached a 9-year low of US$6.3 billion in 2018.8 What might be more concerning is that not only mature gas markets such as Japan and South Korea curtailed investments, all developing nations except China also underinvested during the past five years. The total spending level of developing countries was US$1.5–2.5 billion per annum less than their peak levels of US$7 billion in 2015.9

A possible explanation for this seems to be the demand uncertainty from the industrial sector due to volatility in oil-linked gas prices as well as the easy availability of cheap alternatives such as coal. Moreover, inconsistent state regulations, limited access to capital, and slow-paced evolution of commercial frameworks appear to degrade the investment case—distribution companies are still batting for a fixed annuity-based pricing model that can not only take away the volumetric risk but also allow them to raise cheap capital against that annuity.

With an intense focus on accelerating its gas economy, China implemented several pricing reforms to increase industrial demand—a 20 percent cut in nonresidential city gate price followed by the establishment of local trade hubs and exchanges.10 Even after many thoughtful efforts, the country could only keep its gas distribution investments flat, which may not be enough considering its ambitious road map to expand LNG imports. It seems to imply that gas distribution investors remain cautious and may only buy the story of LNG growth once state policies and regional pricing become consistent and predictable.

Shipping: Sailing in troubled waters?

Shipping and transportation companies, particularly in Europe and Latin America, saw a modest gain in the top line but witnessed one of the roughest falls in their bottom line—the companies’ operating margins fell by 20–25 percent in the past four years (figure 3).11 Unlike other business segments where underinvestment was an issue, huge capital inflows and investment during 2013–2016 seem responsible for today’s oversupplied situation in the shipping market—annual capex spends in the region during 2013–2016 was US$9 billion, as against an average of US$2–3 billion in the past.12 The result: Since 2016, fleet utilization and freight rates (excluding for LNG) have collapsed by 80–90 percent.13

This buildup in capex, or demand estimation, was in anticipation of connecting new supply centers (including shales) with established demand centers. New supplies came, but they changed the state of the O&G industry to a buyer’s market, added significant volatility to crude and natural gas price differentials between markets and grades, and altered established trade flows and shipping routes. The problems of overcapacity were possibly compounded by the potential of a trade war, US sanctions on Iran that reduced ton-mile demand due to fewer long voyages, construction of many cross-country pipelines (Sino-Myanmar, Sino-Russian, East-West Petroline, etc.), and tighter regulations on the emissions front.14

Although rising LNG trade is providing one source of growth to the sector, the performance of oil and product transportation is still key for generating predictable cash flows. It is likely that the opportunities in the liquids market might be limited in the future and could need timely actions to monetize. Some of those include potential increased product movement due to huge investments in the Middle East, International Maritime Organization (IMO) 2020 regulations, and aging very large crude carriers (VLCCs).15 Also, it is time that O&G ecosystem should realize the importance of shipping for future growth and enable an environment where this sector could generate sustainable returns.

Lessons from the downturn

The global midstream industry seems to be in a phase of transition, whether in its growth and investment cycle, the mode and cost of raising capital, or variability and competition in the business. The issues and even the opportunities are often very region-specific in this sector and so will typically be the strategies to successfully navigate this environment. However, some broad considerations could help companies prioritize their focus areas:

- To minimize lag or lead in their infrastructure planning, US midstream companies may adopt new commercial arrangements that optimize risk–reward between operators and shippers. Contracts, for example, where midstream companies pay an upfront rebate in exchange for dedicated throughput, and even linking these rebates to some key upstream performance metrics (drilling or volumetric efficiencies).

- Shipping companies could start to differentiate themselves by delivering extra value to their clients by leveraging digital solutions. By running advanced autotuning algorithms on diverse data sets (spot prices, contractual obligations, port fees, weather data, etc.), shippers can not only help upstream players seize spot opportunities, but also turn idle asset time into opportunity, manage disrupted schedules due to end-market constraints, and understand the exact financial consequence of day-to-day business decisions.

- Gas producers and distributors along with local regulatory bodies can attain last-mile connectivity and overcome demand uncertainty issues by using market-based pricing mechanisms instead of multiple formula-based prices, becoming indispensable partners of governments in making their smart cities program a reality, and exploring new contracting models such as gas trading among bulk gas purchasers to even out seasonality in demand.

Midstream is both a driver and beneficiary of the tight oil boom and rising trade of natural gas worldwide. However, it is essential for midstream companies to stay ahead of evolving market dynamics so that infrastructure, time, and capital are allocated to where they are most needed and become a win-win for all stakeholders. Given supply and demand of fuels determine infrastructure needs, having a complete perspective across the O&G value chain is critical for midstream companies. Explore the entire Decoding the O&G downturn series to gain a 360-degree view on the industry.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More insights for Oil, Gas & Chemicals

-

Oil & Gas Collection

-

From bytes to barrels Article7 years ago

-

Refining at risk Article7 years ago

-

Following the capital trail in oil and gas Article10 years ago

-

A renaissance in the domestic oil and gas industry Article11 years ago

-

Global renewable energy trends Article6 years ago