Cracking the code: How CIOs are redefining mentorship to advance diversity and inclusion Diversity and Inclusion in Tech

20 minute read

09 March 2019

CIOs are increasingly turning to forms of mentorship to help attract, promote, and retain women in the workplace. An effective mentorship and sponsorship approach can also help CIOs eventually win the IT talent war.

Many CIOs have found that attracting, retaining, and promoting IT professionals with diverse backgrounds and perspectives is easier said than done. To meet this challenge, many leading CIOs are increasingly deploying one particularly promising tactic: mentoring. Research shows women and underrepresented minorities who have an effective mentor—not only at work but also in early education—are more likely to enter and stay in tech-related careers.1 Given its promise, how are CIOs encouraging and promoting mentorship within their organizations, and what should they consider as they think about mentorship and sponsorship for the IT workforce?

Winning the IT talent war

Where did Ada Lovelace, born in 1815, find inspiration to become the first computer programmer?2 And how did Katherine Johnson, an African American woman, become John Glenn’s go-to mathematician who verified the computer equations that would control the trajectory of his 1962 space flight from blastoff to splashdown?3 Both women showed a talent for mathematics at an early age, but it was their mentors who set them on their unlikely career paths.

Learn More

Explore the Diversity and Inclusion in Tech collection

Read more from the CIO Insider collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive Leadership content

Many organizations have implemented diversity initiatives that have had little impact on the percentage of qualified women and underrepresented minorities holding IT leadership roles. The challenge is even greater where companies across all industries are competing for highly sought-out IT skills in what some describe as a “talent war.”

Sixty percent of respondents to Deloitte’s 2018 global CIO survey report that their top IT workforce challenge is finding and hiring the qualified talent their IT organizations need to fulfill their business mandates.4 Over the next three years, surveyed CIOs expect to have the most difficulty finding expertise in analytics, cybersecurity, and emerging technologies. Moreover, they need to augment technical expertise with the soft skills needed to collaborate with the business—creativity, cognitive flexibility, and emotional intelligence. CIOs looking to attract talent with this scarce combination of skills also face the challenge of appealing to workers who admire companies committed to having diverse IT workforces and leadership.5

Through our conversations with CIOs, we found that promoting diversity and inclusion within the IT workforce is a top-of-mind issue for CIOs and IT executives—one that is key in winning the war for talent, which also can contribute to innovative thinking and disruption within IT. Eighty-seven percent of CIOs say they have an authentic commitment to diversity and inclusion; however, less than 20 percent of US CIOs surveyed say they have formal initiatives in place to promote workplace diversity and inclusion.6 Clearly, there is more work to be done. One solution to increasing the diversity quotient is to attract, develop, and keep high-performing women and underrepresented minorities in the IT workforce.

CIOs at the vanguard of this effort are taking a holistic approach to building a diverse and inclusive IT culture, which we shared in Deloitte’s CIO Insider, Repairing the pipeline. In this report, the third in Deloitte’s CIO Insider series focused on executive women in IT, we take a closer look at mentorship and how it’s being redefined by CIOs to include advancement and guidance, not only internally within IT organizations, but also extending outward to create an ecosystem focused on enabling women and underrepresented minorities to succeed in IT careers now and in the future.

“Diversity in the IT workforce is probably the single most important factor that we have at our disposal to help build technology capabilities and drive innovation and disruption.”7—Rae Parent

Chief information officer, Corporate Technology, MassMutual

The difference a role model can make

As the role of the CIO shifts from “keeping the lights on” to leading technology-enabled business transformation and innovation, CIOs need IT teams with technical expertise and, more importantly, the ability to drive business strategy. Rae Parent, chief information officer, Corporate Technology, MassMutual, says that with the growing shift in required skills within IT, “the emerging CIO is no longer a career-deep technologist, but more so a technology-savvy business manager who drives innovative technological capabilities. And diversity in the IT workforce is probably the single most important factor that we have at our disposal to help build technology capabilities and drive innovation and disruption.”

It’s safe to say that no one company has cracked the code for building a diverse and inclusive IT culture. Having a mentor can make a big difference for women looking to start or advance in an IT career; in fact, a lack of mentors and female role models are the top two barriers experienced by women in technology.8

In 2018, Deloitte conducted a survey of women IT leaders, 9 most in their late 30s and 40s with seven or more years of work experience. Even in mid-career, many describe still not being taken seriously as women, not being heard, or being passed over for promotion. The women overwhelmingly agreed with one respondent who said, “I had to fight my way to the top without anyone believing I was capable.”

Over half of respondents said they did not have a mentor, but wish they had. Of those who did, male mentors were more common. This was in reverse correlation with age; younger respondents described having had more female mentors. The benefits of sponsorship are also powerful (see figure 1). Another study shows science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) women with a sponsor are 200 percent more likely to see their ideas implemented.10

On the flip side, many IT leaders and CIOs cite having an influential mentor or role model early in their careers help them get to where they are today. The women who did have mentors also described multiple types of mentors and sponsors, such as parents, partners, and professors, as well as direct reports, managers, and senior leaders who helped them in their journeys.11 Mentorship comes in different shapes and sizes—we have found that it’s not a “one size fits all” deal (see sidebar, “Mentorship and sponsorship defined”).

Mentorship and sponsorship defined

There are many ways that companies are addressing the need for effective mentoring—not only for current employees, but also by offering mentoring, sponsorship, and advancement opportunities to potential future employees during college and early education.

Mentoring relationships should be mutually beneficial; mentees receive valuable career advice, while mentors invest in the strength of their organization. Formal mentorship programs should use professional and personal aspirations as criteria to match employees with mentors. Sponsorships can forge cross-divisional relationships between leaders and entry-level employees. Sponsors can use their clout to advocate for the advancement of their protégé—they help them access opportunities and further career ambitions.

The classic business definition of a mentor is evolving as senior leaders recognize that they have much to learn from other generations—both on the job and outside of work. While the value of the programs is undisputed, the most successful relationships tend to be the ones that develop organically—not a “check the box” activity. Terri Cooper, Deloitte’s chief inclusion officer said, “At the core of these relationships, today’s talent is looking for leaders who have three key traits: authenticity, empathy, and willingness to collaborate.”

Traditional mentorship: This mentorship model features a long-term relationship in which a more senior professional offers career advice to a junior person. To be effective, each person should understand the other’s role and clearly define their expectations and goals upfront. A mentor acts as a confidant, shows the way to navigate workplace challenges, and has the “hard talks.” Mentoring promotes diversity by providing equal opportunities for every employee to develop and advance professionally. It helps organizations identify high-potential employees and ensures they are provided with the resources they need to develop and feel supported.

Sponsorship: An experienced senior person can sponsor a mid-level employee by actively advocating for the advancement of this person, often by providing exposure and engagement with senior leaders. A sponsor can speak to the person’s work performance and should be willing to advocate and “bang the table” for advancement and growth.

Reverse mentorship: The benefits of mentorship often flow both ways. In the concept of “reverse mentorship,” a junior person informs and teaches a more senior professional, often about new technologies, innovative approaches, and cultural/generational differences. Reverse mentorship often happens organically in a traditional mentorship relationship.

Building and measuring relationships that work

When we asked a group of 40 leading female CIOs to identify the single factor that keeps women out of IT leadership positions, more than half cited the lack of mentorship to help develop the skill set needed as the top factor, followed by lack of opportunities and work/life fit.12

As CIOs and other leaders look for opportunities to pair employees with mentors and sponsors, they should consider the specific needs of technologists within their organizations; sometimes a mentor outside of IT can help provide the broader business perspective and leadership employees need to pivot in their careers. Ideally, different individuals fill the mentor and sponsor roles because each serves distinct but complementary purposes and the roles are well defined.

The success of these relationships, whether formal or informal, typically hinges on natural chemistry and shared expectations going into the relationship. Maya Leibman, executive VP and chief information officer, American Airlines Group Inc., stresses that setting clear expectations upfront increases the effectiveness of the relationship. “A mentee needs to understand what she wants to get out of the experience and be able to articulate that to her mentor. And she needs to come with questions, stories, and examples to help direct the conversation to the areas where she needs help.”13 On the other hand, mentors should clearly explain what type of help they are willing and able to provide.

Rae Parent echoes the value mentorship relationships can have in dispelling stereotypes about technologists and outlining career paths within IT—especially for nontechnologists who may be interested in IT and can bring unique perspectives and diverse thinking to the IT organization.

She uses herself as an example, as a success story of a nontechnologist who has risen through the ranks within IT. Parent often tells her own narrative to underscore how critical diversity is within IT. “I majored in English, with a minor in communications,” she says. “I fumbled my way through learning how to code. But it taught me a different way to think, it helped me establish credibility, and it led to an exceptionally rewarding IT career.” Parent adds, “People often struggle with being effective mentees and being effective mentors. I tell my mentees our success is measured on, ‘If when you have a problem, or when you have an opportunity, you want to give me a call and bounce it off me.’ That is a successful mentor/mentee relationship.”

Shelley Zalis, CEO of The Female Quotient, reminds us that mentorship comes in different forms, “We believe in mentorship in the moment. There’s no one mentor that will give you everything. You can get bits and bytes from different people who have been there, done that. Mentorship is not just about wisdom being pushed down, it’s about sharing knowledge all around. And when it comes to sponsorship, everyone should have an advocate. The best sponsor is someone not like you, so you can grow outside your comfort zone.” 14 She also finds that mentorship and sponsorship programs can have a placebo effect and are not serving their intended purpose of advancing the pipeline of women.

While mentors and sponsors can inspire, propel, protect, and put their social and political capital and credibility toward advocating for advancement, IT organizations should think through how the investment, both time and people, and the benefits are measured and reported. Zalis also suggests, “First, we need to define the roles of the mentor and sponsor and create measurements for accountability. That is how we can truly leverage these relationships to move women from middle management—or what we call the ‘messy middle’—into leadership positions.”

Mentoring across: Employee resource groups and peer-to-peer networking

There can be a level of confidence in numbers—and formal or informal programs to facilitate mentoring and networking among peers with similar professional and personal attributes—career level, education, personal interests, etc.—can be critical in keeping women in IT. Angela Venuk, vice president, IT project management and governance for GameStop Corp., came close to leaving technology for good early in her career. She worked for a fast-growing technology company where she put a lot of pressure on herself to compete and be successful, believing that technology had to be a 24/7 job. When she married and decided to have children, she could not imagine that she could successfully combine a technology career with family life.15

Unfortunately, her story is a common one. What if Venuk had had a role model or mentor who could provide advice about how a working mother can succeed in an IT environment? When she was promoted, she became that advocate for women in a predominately male work environment. GameStop established several employee resource groups (ERGs) focusing on women leadership, veterans, African Americans, Hispanics, and employees with various disabilities. Each group has a leadership sponsor charged to advance and celebrate diversity and inclusivity in the work environment. The objective of the women’s leadership groups is simple: Prepare women and underrepresented minorities to be the best person for the job—and give them the confidence to put themselves out there. Venuk, who has participated in the women’s leadership program, explains, “The program has committees and sub-committees that are focused on the objectives of the program and has helped women in two-fold. One, it gives them a channel to network and learn from one another, and second, it provides them opportunities to hold leadership positions as part of the committee format. These positions give them real-life practice for leading a team of colleagues to build their capabilities as leaders.”

Leaders at GameStop have also established a cohort program called Amplify. Venuk is one of the leaders who leads a cohort of eight women from various functions of the business through a 10-month curriculum and provides opportunities to amplify their leadership. The program, which is sponsored by senior leadership across the company, just finished its second round and has had five women nominated from IT in each round. Women think through how to amplify their brand, influence, resilience, business acumen, and network among their peers. “While these programs are not just focused on technology, we've deliberately tried to include as many women from IT to really help them break the perceived glass ceiling in technology,” Venuk says.

Another example of peer-to-peer mentoring is Salesforce’s adoption of the Hawaiian concept of Ohana—that families, whether blood-related, adopted, or selected—are responsible for one another. Their Ohana groups are employee-led and employee-organized groups centered around common life experiences or backgrounds, and their allies. Ohana groups range far beyond typical ERGs, including groups for environmentalists and people of faith.

Jo-ann Olsovsky, EVP and CIO of Salesforce, says the Ohana groups are a key factor in driving inclusion within her extensive, diverse global IT team, “Our global IT equality council celebrates and honors the diverse identities of our IT Ohana. It’s the way we bridge global teams and drive positive outcomes throughout the company. It’s ingrained in our culture.”16

Everyone grows through reverse mentorships

The benefits of mentorship can go both ways, helping experienced managers as well as more junior employees. Mentorship often helps eliminate unconscious biases related to age, gender, and race, among others, by investing mentors in their mentee’s success. Likewise, reverse mentorship can help leaders stay in touch with their organizations and customers, while providing junior employees opportunities to understand and be heard by more senior and experienced people.

Reverse mentorship can be particularly important in IT. As digital natives, younger employees can push senior leaders to leverage emerging technology skills and help shift their thinking on how to incorporate these technologies. Diverse perspectives working together can lead to innovative solutions to old problems.17

Organizations can create formal opportunities for generations to learn from each other. For example, “lunch and learn” sessions can offer open and free-flowing dialogues between technology leaders and more junior employees. One Generation X technology executive observed, “Millennials see a problem or something that could work more efficiently, and they think, ‘we can fix this.’ Where leaders may see barriers; younger professionals see opportunities.”

Making it matter

Like diversity and inclusion initiatives, mentoring programs need sponsorship from leadership—often up to the board level. Deloitte’s 2017 Global Human Capital Trends report revealed that 38 percent of executives report that the primary sponsor of the company’s diversity and inclusion efforts is the CEO. Sponsors, mentors, and mentees also need measurable metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of the program on an ongoing basis.

When mentoring relationships—whether traditional, reverse, or peer-to-peer—occur informally, without stated goals and KPIs, there’s no objective way to evaluate their effectiveness. An ERG, for example, that develops from an individual’s passion for equality—but without formal leadership support and commitment—may offer a safe space for women and underrepresented minorities but have little effect on preparing and moving women and underrepresented minorities into leadership positions. In contrast, formal mentoring programs and ERGs with clear mandates and goals and support from leadership can provide measurable results that spotlight progress and opportunities for improvement.

Looking outward to build the long-term pipeline

What IT organizations are doing outside their four walls can be as important as their internal initiatives, especially when it comes to building a talent pipeline for long-term success. CIOs from companies of all sizes are collaborating with nonprofits, universities, community colleges, high schools, middle schools, and even elementary schools to advance interest in STEM careers among young people—especially young girls.

Starting as early as possible

Kateau James was one of the lucky girls. She took her first computer programming classes in 9th grade. At age 14, she applied for an engineering apprentice program. Several girls were selected—including James—although the admissions committee assumed that she was a boy. Remarkably, all of the girls ended up in a technology career. Today, James is a technology managing director at Deloitte.18

Her story isn’t typical. Many girls begin to lose interest in science and math before they even enter middle school. Perhaps because they succumb to stereotypes (“boys are better at math and science than girls”) or maybe it’s lack of encouragement from family or teachers. For CIOs to fill their long-term talent pipeline, they should engage girls early and overcome these perceptions. One way to approach this is to provide female role models and innovative early mentorship opportunities.

Salesforces’s Olsovsky believes that an important part of her job is being a role model for others—especially girls. “It’s important to get out into the community and all of our friend and family networks, and be part of the school systems, starting in junior high and high school—and even younger if you can—to help kids recognize all that they can accomplish,” she explains.

Her commitment is backed by research. A recent survey of more than 6,000 girls and young women aged 10–30 showed girls’ negative perceptions of STEM careers can change. Girls who know a woman in a STEM profession are much more likely to feel confident when they engage in a STEM activity (61 percent versus 44 percent).19 Unfortunately, many girls do not have a female role model in a STEM career.

The survey also showed that many girls do not realize that technology and computers can be used to help others. When girls are given examples of how technology can help the world, their positive perceptions of computer scientists improve by one-third, from 41 to 74 percent, increasing the likelihood that they will pursue technology careers.

Collaborating to build an ecosystem focus on the larger diversity agenda

Some corporations are building their future IT pipeline by partnering with schools and nonprofits to break down the barriers—real and perceived—that prevent young people, especially girls, from entering STEM professions.

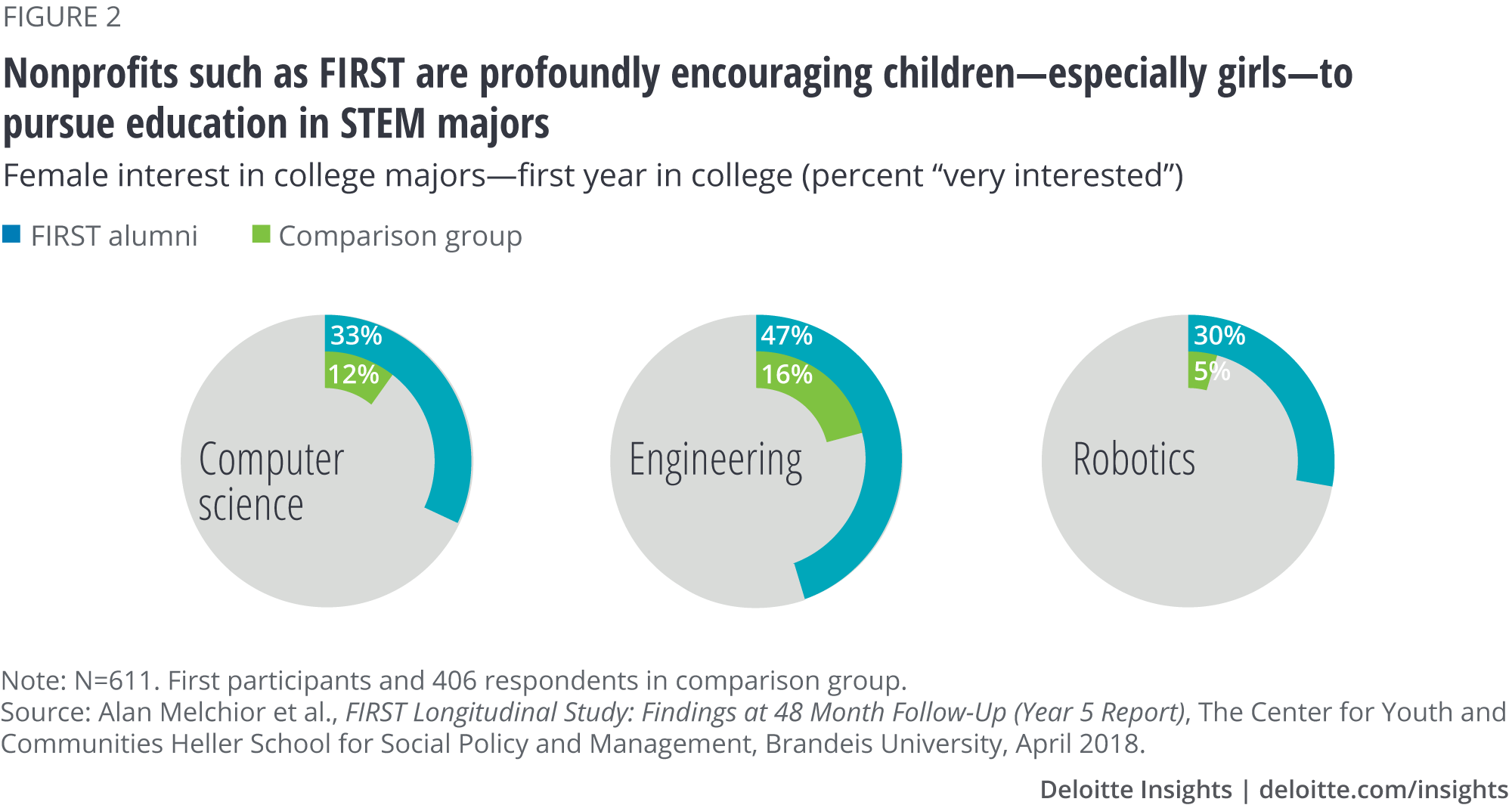

For example, FIRST® (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) is a global nonprofit that operates hands-on robotics programs for kids aged six to 18 years. Their goal is to inspire kids to become science and technology leaders by engaging them in fun, mentor-based programs. They offer age-appropriate learning challenges—spanning elementary through high school—that require a team of students, with their mentor’s help, to use STEM knowledge to solve a real-world problem. The organization works with more than 200 of Fortune 500 companies, which provide financial support, as well as a network of volunteers who serve as student mentors.20

A five-year longitudinal study showed that, compared to their peers, graduates of FIRST’s high school-level program are nearly twice as likely to be interested in majoring in computer science. These impacts are amplified in female alumni: They are three times more likely to want to major in computer science and engineering, and five times more likely to want to major in robotics than their peers (see figure 2). Overall, 40 percent of FIRST’s female alumni took a computer science class during their first year of college versus 11 percent of young women in the comparison group.21

More CIOs are now helping younger generations learn the skills they will need to join the IT talent pipeline. They are establishing win-win partnerships with organizations who have a commitment to encourage young girls and underrepresented minorities to help them understand and navigate the opportunities in STEM-related careers.

“It’s important to look at it as an ecosystem because there are a lot of different groups that have to come together, whether it's teachers or parents or universities or private companies like American Airlines, in order to move the needle on this, and we all approach it from a different, unique perspective,” says Leibman.

With Leibman’s sponsorship, American Airlines partners with two local organizations. One of the core programs that the IT organization at American Airlines sponsors is the SO SMART program—a mentorship program focused on young girls aged nine to 12 years, which mentors and teaches them about technology while providing them with career and life guidance. American Airlines also partners with the Dallas Independent School District to develop a software development and infrastructure support curriculum and programs focused on helping students graduate with a high school diploma and either an associate degree or 60 hours of college credit—with access to mentors from American Airlines and other private organizations.

The benefits of company sponsorship of youth mentorship programs extend beyond inspiring students to pursue STEM careers. When employees engage in these types of mentorship programs, they can develop leadership and negotiation skills through the experience of corralling a team of young people. Mentors who participate with a technology-focused team also gain practical exposure to new technologies—such as robotics, machine learning, and other tools the team is employing.

Getting back on campus

Even among those girls who pursue STEM education, fewer college women than men who major in computer science or engineering actually enter a STEM career. In a 2018 report, the Pew Research Center found that undergraduate women who major in computer engineering and computer science are less likely than their male classmates to be working in a computer-related occupation after graduation (38 percent versus 53 percent). The reasons college women gave for not working in technical fields include discrimination in hiring and promotion, difficulty balancing work and family, and lack of confidence that they can succeed.22

Lack of work/life balance is a perception that should be addressed. Olsovsky says she regularly encounters high school kids who do not want to work in IT because they think there is no work/life balance. She disagrees, “I’ve always thought it was the opposite—in IT, we actually have more ability to flex. My husband and four kids would tell you we have figured out a routine, and have found the right balance so that everyone in the family supports each other and makes it all work.”

A diverse slate expands beyond the outward appearance of a candidate, and includes thinking about recruiting from a diverse mix of colleges. For instance, hiring outwardly diverse candidates from Ivy League schools does not guarantee diversity of thought. CIOs should broaden their campus and experienced-hire search to truly build diverse teams with diverse perspectives.

Some companies are working to change young women’s perceptions of technology professions by offering opportunities for college women to work as interns in IT before they enter the workforce. Sheila Jordan, SVP and CIO of Symantec, brings in a large group of interns every summer. In 2018, she hired 60 interns—and 50 percent were women. Jordan reports, “These women were amazing, and just so impressive. The talent is here; the interest is there. You have to spend time to find those women and young girls. But we also need to do a better job at creating environments for women to continue to succeed; this is where tech specifically could do a better job.”23

Lessons learned

While mentorship is only one component of attracting, hiring, and retaining a diverse set of IT talent, the lack of mentors, sponsors, and role models remains a big barrier to parity within IT. Through interviews and research, we have determined that the following considerations can help CIOs think through the value and impact of mentorship as part of their diversity and inclusion initiatives.

1. Make it tangible

Formal mentorship programs are an important element of advancing diversity and inclusion, but they should have a structure that is tangible and can be evaluated.

Encourage formal development plans including stretch projects and assignments, opportunities to take on different roles, training programs, and coaching.

Measuring progress is important, but you should create an environment where mentors understand their roles and are empowered to support the advancement of their mentees.

Mentorships may fail when participants don’t have reasonable expectations for the outcome. Define metrics, timelines, outcomes, and responsibilities for the mentor and mentee upfront to hold everyone accountable.

2. But be flexible

Mentorship is not a one-size-fits-all deal. Individuals and their IT organizations may find that some types of mentoring work better for them than others.

Don’t expect cultures to change overnight. Some organizations look for a steady increase in women and underrepresented minorities over time as a measure of mentorship effectiveness.

Focus on cultivating a culture and creating an environment where everyone has equal access to mentorship opportunities, regardless of gender.

3. Lead from the top

Executive and board support are critical. Leaders should hold each other accountable through routine check-ins and report outs that focus on continuously improving programs.

Leaders can express mentorship and sponsorship programs in terms of metrics on gender parity across all levels of the organization and then measure the impact against key financial indicators over time.

Leaders also need to take personal responsibility for demonstrating inclusive behaviors and share the business case for diversity and inclusion. Our research indicates that organizations with inclusive cultures are six times more likely to be innovative and agile, eight times more likely to achieve better business outcomes, and twice as likely to meet or exceed financial targets.

4. Expand the focus

Realize that mentorship comes from many types of experiences and often occurs in the moment. It’s important to recognize that people may take away different things from different mentors and experiences.

Look for opportunities to partner with outside STEM organizations to mentor and provide role models for young people to make a long-term impact on the IT talent pipeline.

Partner with external organizations that may help pave the way to build meaningful commitment to advancement programs—sponsorship, returnship, and mentorship.

Peer-to-peer mentoring through networking and ERGs can help create ongoing opportunities for individuals to discuss issues and gain support.

Start at home and in your community. Be a role model for girls and young women by offering to visit and speak in classrooms and bringing youths to visit your organization.

The essence of mentorship

Ada Lovelace’s mother encouraged her daughter to pursue mathematics as an antidote to the irrational temperament of her father, poet Lord Byron. And Katherine Johnson’s mastery of math was recognized and advanced by the sponsor who selected her as the only woman among three African Americans to attend graduate school at West Virginia State University.

Developing an IT talent strategy that incorporates mentorship and sponsorship is an important arrow in the CIO’s quiver for winning the IT talent war—one that benefits individuals and organizations in many ways.

The essence of mentorship is to learn from another person—with different experiences, ethnicity, age, gender, personality, style, and ways of thinking all being part of the equation. When we started this project, we had planned to conclude with a “how to” list outlining how CIOs are using mentorship today to shore up their IT capabilities. But our conversations with CIOs prove that there’s no “right” way to mentor and mentorship comes in many different flavors. Indeed, approaches to mentoring are as diverse as the individuals involved. Perhaps more importantly, mentorship can be most effective when it reflects the authentic, generous selves of the mentor and mentee to help and learn from each other, which leads to diverse mindsets and thinking.

More in CIO Insider

-

Technology and the boardroom: A CIO’s guide to engaging the board Article5 years ago

-

Digital vanguard organizations Infographic5 years ago

-

Repairing the pipeline: Perspectives on diversity and inclusion in IT Article6 years ago

-

Trends in CIO reporting structure Article6 years ago

-

Manifesting legacy: Looking beyond the digital era Collection6 years ago

-

Smashing IT’s glass ceiling: Perspectives from leading women CIOs Article6 years ago