From siloed to distributed Blockchain enables the digital supply network

13 minute read

01 February 2019

Blockchain offers great promise in relieving many supply chain pain points and enabling the ongoing shift from linear supply chains to connected digital supply networks.

Blockchain’s relevance to digital supply networks

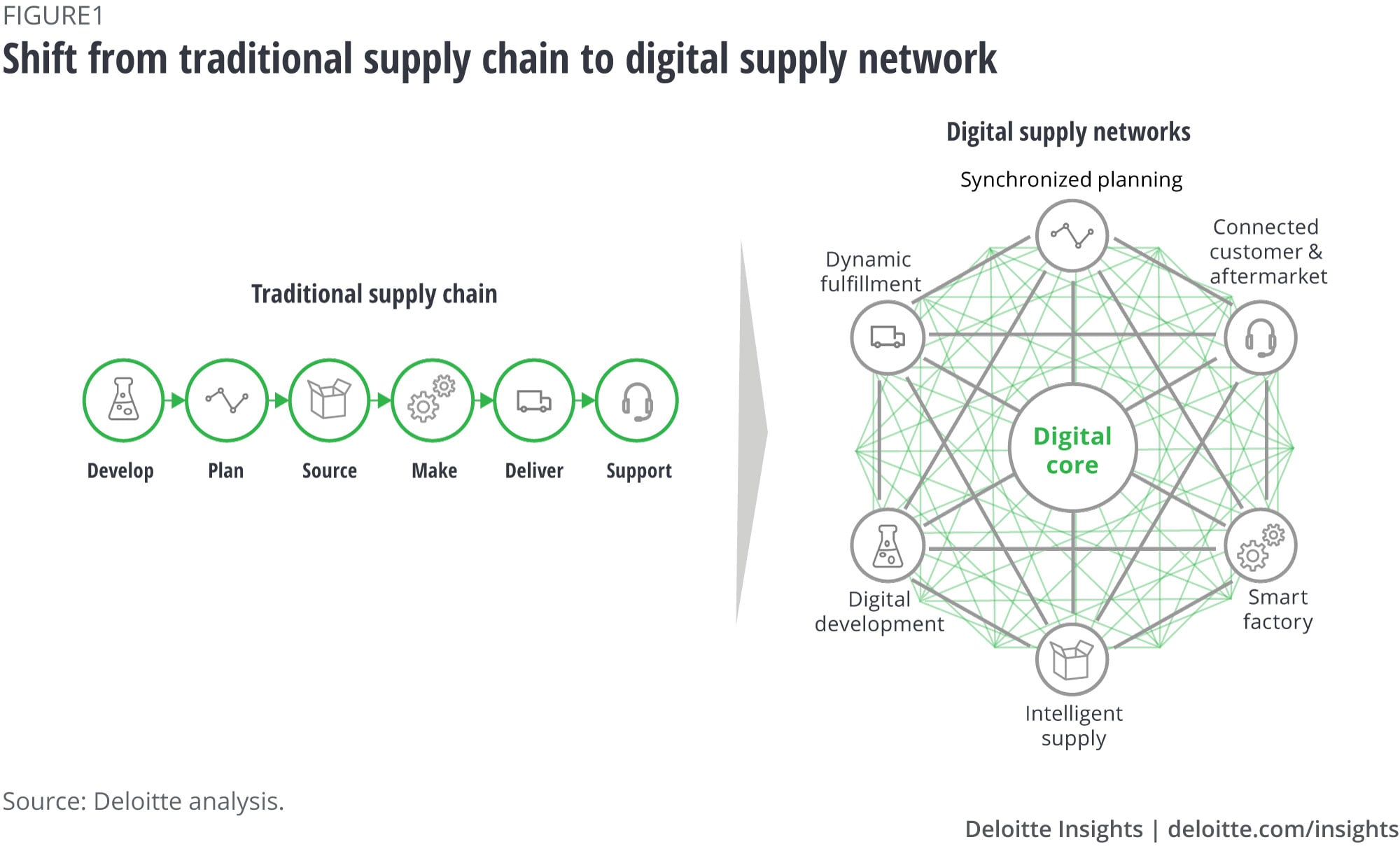

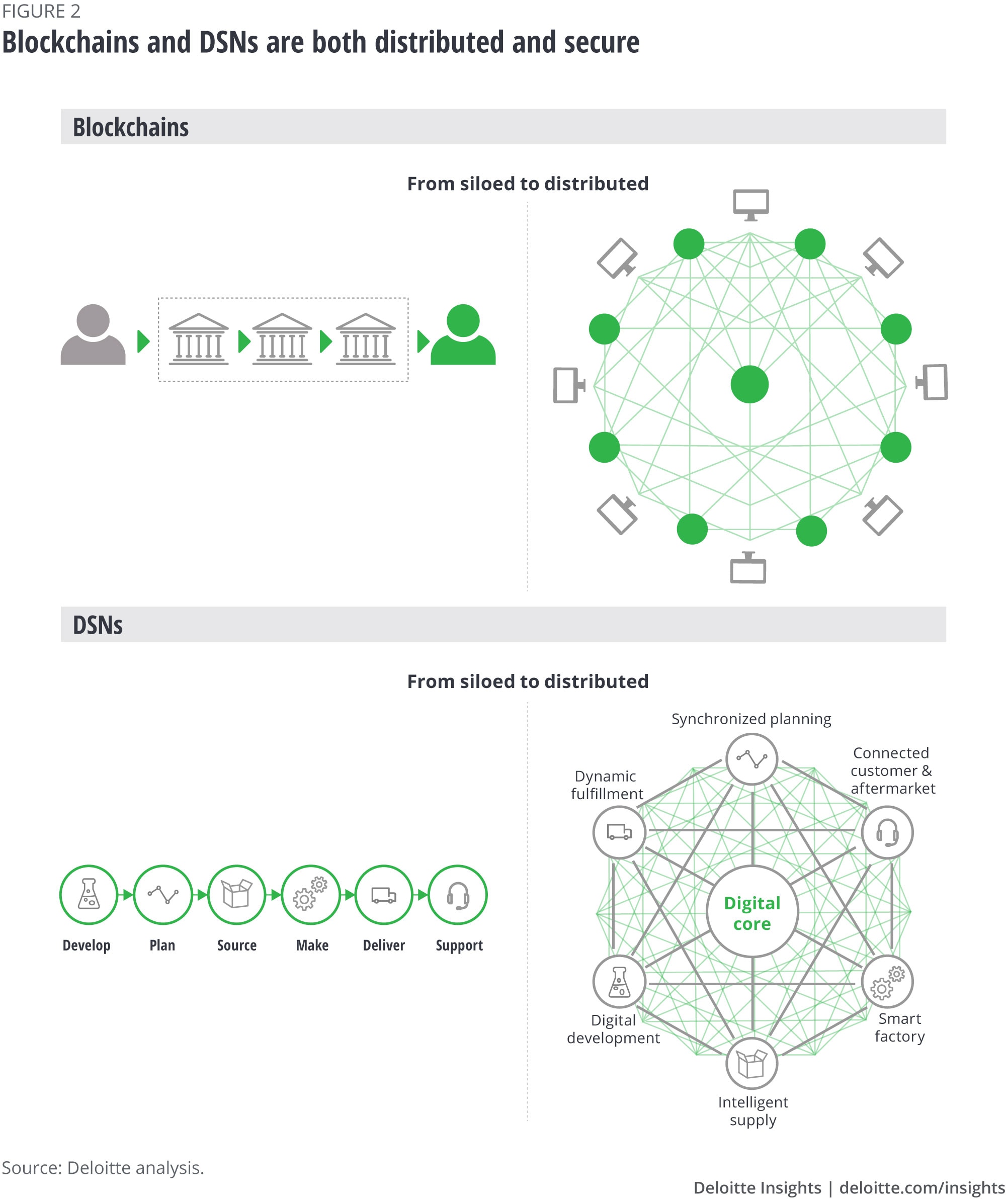

A growing digital divide exists between organizations that embrace the transition from linear supply chains to digital supply networks (DSNs)—and those that do not. This evolution of linear and relatively siloed processes into a set of dynamic and interconnected nodes creates significant operational advantages for organizations, enabled by a set of wide and diverse technologies.

For logisticians and supply chain managers warily eyeing these changes amidst the sea of headlines, this report centers around one emerging technology, blockchain, and its role in the future of supply chain.

As Deloitte’s earlier research asserts, blockchain and its capabilities—disintermediation, immutability, and auditability—offer a great deal of promise in relieving many supply chain pain points.1 After all, blockchain is a transaction mechanism, and supply chain is fundamentally about a life cycle of value-added transactions among stakeholders. And as a distributed peer-to-peer protocol whose incented stakeholders securely share critical information, it’s one of the technologies that will serve as an enabler of the ongoing shift from linear supply chains to the connected state of digital supply networks.

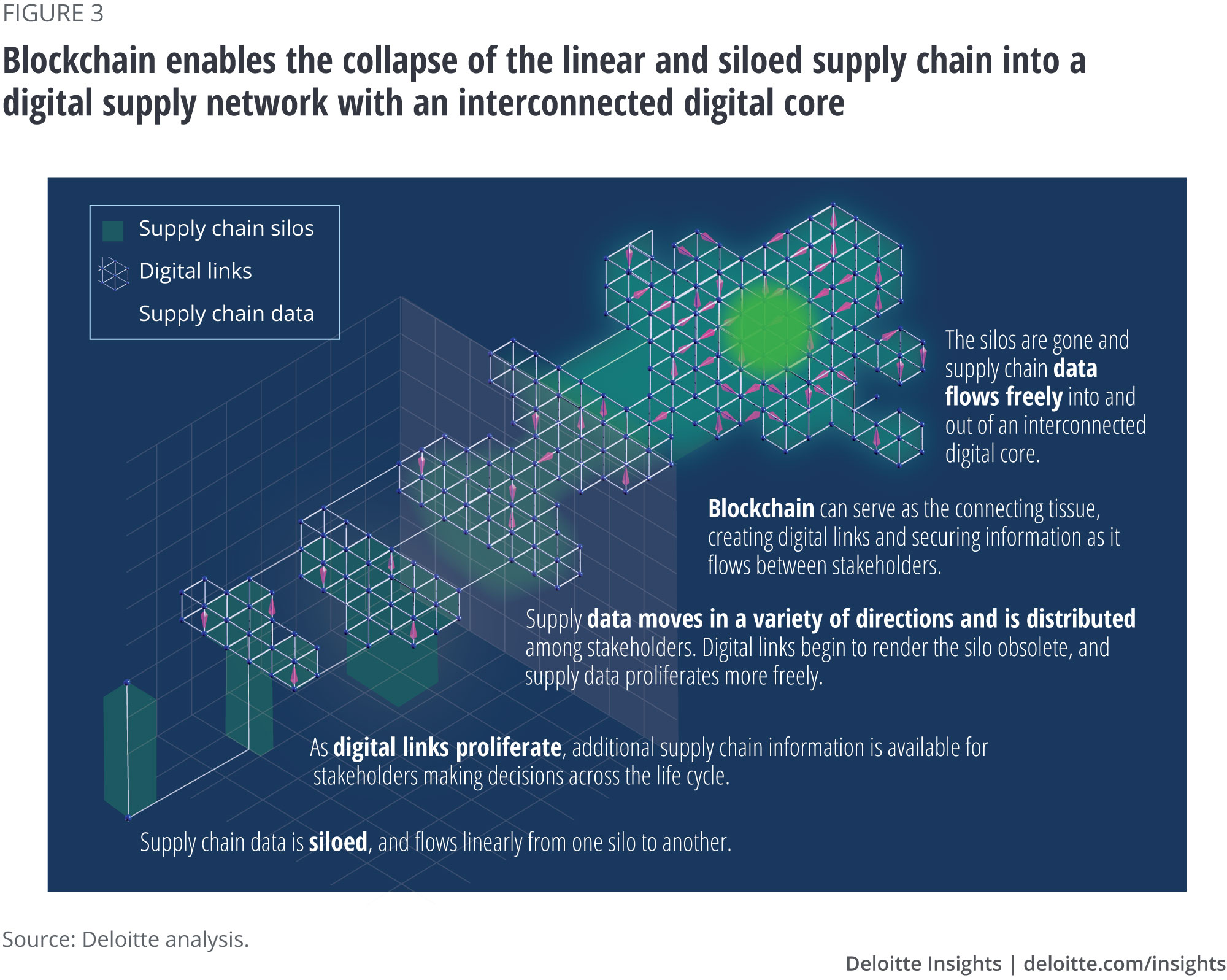

As this process unfolds, what was siloed will increasingly become distributed as blockchain enables existing linear systems and data to unite with commonly relevant sharing of information. Perhaps more importantly, as that transition continues, silos collapse to reveal a new interconnected digital core, with blockchain as the connecting tissue among the supply nodes, a critical element of the digital core stack.

In this report, we attempt to expand the discussion around supply chain and blockchain. In so doing, we provide an informal taxonomy of two primary adoption areas within supply chain, and then examine blockchain’s specific role as an enabler—and sustainer—of the DSN. We conclude with our thoughts on how to identify an explicit value proposition for blockchain within a supply chain context, some basics on how to get started with implementation, and a brief look at what lies ahead.

For more background on blockchain, including its foundational operational features, please see: Blockchain: A technical primer.

For more information on the DSN, see: The rise of the digital supply network.

From traditional supply chains to digital supply networks

Figure 1 depicts the transformation of a linear and static supply chain sequence to a dynamic digital supply network, with a digital core. In a pre-DSN state, information travels in a step-by-step sequential manner—from develop to support. DSNs overcome the delayed action–reaction process of the linear supply chain by employing real-time data to better inform decisions, provide greater transparency, and enhance collaboration across the entire supply network. There is potential for interactions from each node to every other point of the network, allowing for greater connectivity among areas that previously did not exist.2

The collapse of traditional supply chain nodes into an open, digitally interconnected network likely creates new value and new opportunities for cost reduction, such as the ability to more closely tie procurement processes to inventory or better communicate with customers on the status of their orders. This mirrors the value creation that blockchain provides, both in the formation of connected nodes and in the move from linear and often-siloed transaction processes toward a shared accounting of the state of an asset, as depicted in figure 2.

Blockchain in a supply chain world: Two primary adoption areas

Typical examples of blockchain within a supply chain context tend to focus on physical-asset-tracking applications, such as tracking the location of an asset at a given point in time. This makes sense given that blockchains are asset-exchange mechanisms and supply chains often remain focused around the movement of physical products. But blockchain can be used by stakeholders for much more than the tracking of assets. It is thus important to move the supply chain and blockchain discussion beyond the traditional and relatively narrow realm of asset tracking and into both the wider range of asset management applications—tracking, tracing, and discovery—and from there into the even broader domain of supply chain visibility and data protection applications.

Moreover, assets in a blockchain context may refer to more than just information that describes the state of a physical asset. Such assets may include native digital assets as well—those assets that never assume a physical state and are not necessarily tied to a physical asset or process. Examples of such native digital assets may include descriptive information contained within a software license, or a unique identifier that refers to a largely digital business process, such as an invoice number or IT service ticket number.3

Toward that end, we identify two primary adoption areas for blockchain applications to serve as an informal taxonomy or a way to think about which supply chain areas blockchain is likely to impact:4

Asset management. A supply chain has a range of assets in motion at any given time. Knowing where these assets came from, where they are, and what refinements to each are made along the way is critical to the effective running of an organization. As such, the application of a blockchain layer can help in the management of those assets in three specific ways—tracking, traceability, and provenance. Asset tracking focuses on capturing the state of a physical or native digital asset in real time or at predetermined times or conditions, and potentially includes locational or other specific asset attributes. Traceability focuses on the capture or recovery of the history of an asset, often to pinpoint a flaw or fault, but also for auditability and compliance purposes. Provenance use cases in blockchain concern transfer of custody and tend to focus on high-value assets, where reassurances about counterfeiting, point of origin, or lineage are treasured.

Visibility and data protection. Supply network visibility and data protection use cases are those where a set of stakeholders within a supply chain identify commonly relevant information and use a blockchain to securely share that information for an anticipated common benefit. These use cases tend to derive from business processes not rooted in a physical asset. They are broader than individual asset management use cases and often focus on native digital assets. Importantly, they can tie the broader elements of an organization’s supply chain together—linking together procurement mechanisms, asset management, operations and maintenance, and sourcing and inventory systems—and eventually linking each of these processes to the broader organization: finance, human capital, IT strategy, etc.5

Blockchain as a digital supply network enabler

Earlier, we observed the parallel between the decentralizing, distributed nature of blockchain and the journey from linear supply chain to DSN, and identified two likely adoption areas for blockchain within a broader supply chain context. But the question remains: As we continue to progress toward DSNs, what specific roles does blockchain play?

Away from silos and toward distribution

The first specific role for blockchain within DSNs is as a uniting layer allowing information to move from a siloed state toward a distributed one. Recall how information generally flows in a traditional, linear pre-DSN supply chain: develop, plan, source, make, deliver, support. Each step in this linear chain is largely dependent on the step before it. Inefficiencies and mistakes in one step may propagate to subsequent steps. In addition, each linear step is also largely insular and siloed, resulting in a cascade of inefficiencies and lacking the visibility that may provide insight into the processes within other steps and the accompanying opportunity for course correction as needed.6

The first specific role for blockchain within DSNs is as a uniting layer allowing information to move from a siloed state toward a distributed one.

A blockchain layer can serve to unite the siloed systems and data of the linear pre-DSN environment with transactions of commonly relevant pieces of information. Essentially, blockchain can serve as the transaction fabric uniting existing linear systems; it does not require a “rip and replace” scenario.7 By distributing predetermined categories of information between existing systems and stakeholders, what is created is not a new system but a digital realization of the existing ecosystem of which these participants are already a part. Insights into one portion of the life cycle are shared with stakeholders in others in a developed application programming interface (API), and a new degree of transparency leapfrogs traditional silos, freeing up data to travel in less rigid and linear a fashion. However, we must emphasize that blockchain does not summarily resolve all barriers to cooperation: These stakeholders will still need to have, or be able to obtain, the predetermined categories of information about an asset, render it readable by the format that the API requires, as well as address other critical data standardization issues.

The output of applying blockchain in this manner is not a DSN, per se, but it’s potentially one element in getting there. The process of transitioning away from a siloed and linear method of interaction is thus the first enabling role of blockchain in the shift toward DSNs.

Blockchain as the connecting tissue

The second role is what occurs as the distribution process progresses. The multiplication of cross-life cycle digital links continues between supply chain participants and nodes and their existing functions, and, over a long enough time, something new is created. With each additional connection between the nodes and each tie back from the supply chain functions to the enterprise operations of an organization (such as finance), the silos start to collapse, revealing in their wake an interconnected core (figure 3).

In this instance, the second and specific role of blockchain is to serve as the connecting tissue itself, an enabling component of a dynamic, interconnected, new core stack that securely ties assets—be they physical assets, enterprise workflow outputs, or other—together.8 This enables a DSN that represents a supply chain ecosystem to emerge. It also inspires the ability to reimagine enterprise functions, such as finance, as well as middle- and back-office functions as part of larger global ecosystems supported by digital technologies.9

The second and specific role of blockchain is to serve as the connecting tissue itself, an enabling component of a dynamic, interconnected, new core stack that securely ties assets—be they physical assets, enterprise workflow outputs, or other—together.

And, as ever more information is rendered digitally within these interconnected networks, blockchain can potentially serve as the mechanism for its exchange. Indeed, blockchain may even become one of the primary mechanisms for exchange of industrial information (a topic for future analysis).

The sensors are coming

As these evolutions take place within organizations, another critical element of the broader digitization process is the linking of the digital and the physical. Why are organizations pursuing the digitization of their physical assets and accompanying processes? Not just because the cost of chips and data storage continues to decline, but, more importantly, because organizations have identified business problems that can be addressed using sensor data.10 Indeed, discussion around blockchain and DSNs very often includes physical assets and, accompanyingly, sensor data. In supply networks, the opportunities for the deployment of sensors are vast, and the risks of inadequate asset visibility or system transparency are real.

Sensor adoption can also be understood along a curve. Solving an important business problem, say for a very unique pain point or particularly sensitive asset, such as a critical manufacturing subcomponent, will often justify a larger investment to address the problem or manage the asset. This higher cost may come from the procurement of a more advanced sensor, a greater number of sensors, or a more robust pace of sensor data collection. However, as the costs of sensors and of the chips in them drop, these more substantial means of asset management will continue to cost less and thus be likely suitable as solution elements for a greater and greater range of lower-value assets. This is how we move into a world of ubiquitous sensors.11

The value proposition: Just because you can doesn’t mean you should

In much of the popular literature, blockchain technology is often touted as a series of “blockchain can” capabilities, with the technology, and not the implementing stakeholders, as the actor.12 This is typically linked in some generic way to how blockchain will solve a particular problem, with benefits mentioned but no real detail about what drives the cooperation between stakeholders or the specific assets they’ll transact between each other. Often missing, or not emphasized, in the literature is a description of the specific value proposition justifying the costs of implementation and maintenance of the protocol.

There is no magic in blockchain. It has value because it offers a secure and distributed mechanism for value exchange.13 The maintenance of that mechanism incurs costs, costs that are presumably lower than current centralized processes or add enough value to justify bearing them. When large-scale investment takes place without a mature concept of how the end result will compare with anticipated benefits, necessary experimentation can wind up sidelined, and investment likely dries up.

Take the case of asset tracking, for example. When network stakeholders share mutually relevant information about an asset, they can benefit from decreased friction across the asset’s life cycle, or the ability to use this shared information to optimize operations. This, in turn, incentivizes the cooperation between those stakeholders. So, the value proposition is that the investment in this method of cooperation is either cheaper than the existing siloed or insecure way of doing things or adds enough benefit to justify any additional cost incurred if no process for cooperation between the stakeholders existed beforehand.

What’s needed is for that value proposition to be made explicit and, wherever possible, quantifiable. Where the benefits of a blockchain-based solution are measurable—the decreased friction, the security, potentially the uniting of existing systems, etc.—and outweigh the costs in the context of the solving of a business problem, a value-driven—and explicit—case for adoption is made. Put more simply, the space between the cost of implementing a blockchain solution and the higher cost of an existing centralized or shared legacy process is where enterprise adoption will be found. And the critical element here is that it’s not a function of gaining capabilities but of reducing friction, and the resulting reduced cost and “process drag.”

The space between the cost of implementing a blockchain solution and the higher cost of an existing centralized or shared legacy process is where enterprise adoption will be found.

Getting started with an implementation roadmap

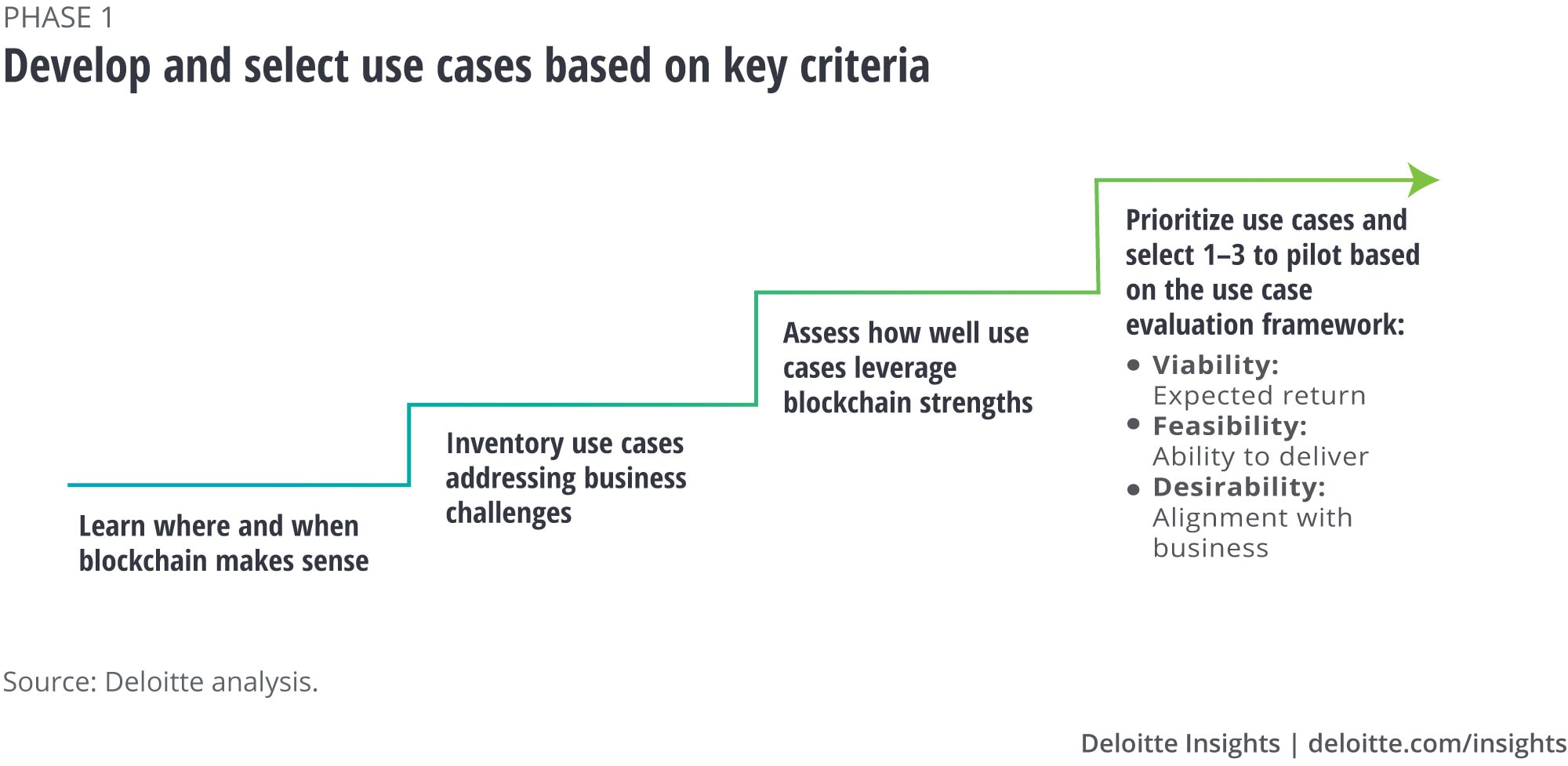

How should an organization actually get started moving from value proposed to value realized? One way is to follow a three-phase implementation roadmap, first introduced in Blockchain to blockchains, to help solutions grow in scope, scale, and complexity.14

Phase 1: Develop and select use cases based on key criteria

Not every supply chain challenge necessitates a blockchain solution. After understanding where and when blockchain makes sense, it is critical to build an inventory of use cases that answer to specific business challenges. To do that, forget about blockchain for a bit. Instead, work with all of the DSN stakeholders—from logistics and distribution experts to the product team to sourcing and procurement staff—and hammer in on the major supply network problems that the organization is facing. As your organization seeks to address these challenges, blockchain may emerge as an effective solution for some of them. However, it is individual to each enterprise. For one organization, blockchain may be most effectively used for asset tracking; for another, data protection. Those supply network challenges that leverage blockchain strengths should be considered further, and those that do not can be rapidly identified as requiring other solutions.

Critical questions to answer for phase 1

- What is the asset to be transacted across nodes? Is it a physical asset or derived from a physical process?

- Which nodes are involved in the asset life cycle?

- How will the state of the asset be verified? The states could include transfer and current ownership of the asset.

- What incentivizes the stakeholders to work together, or consort?

- What problem is solved?

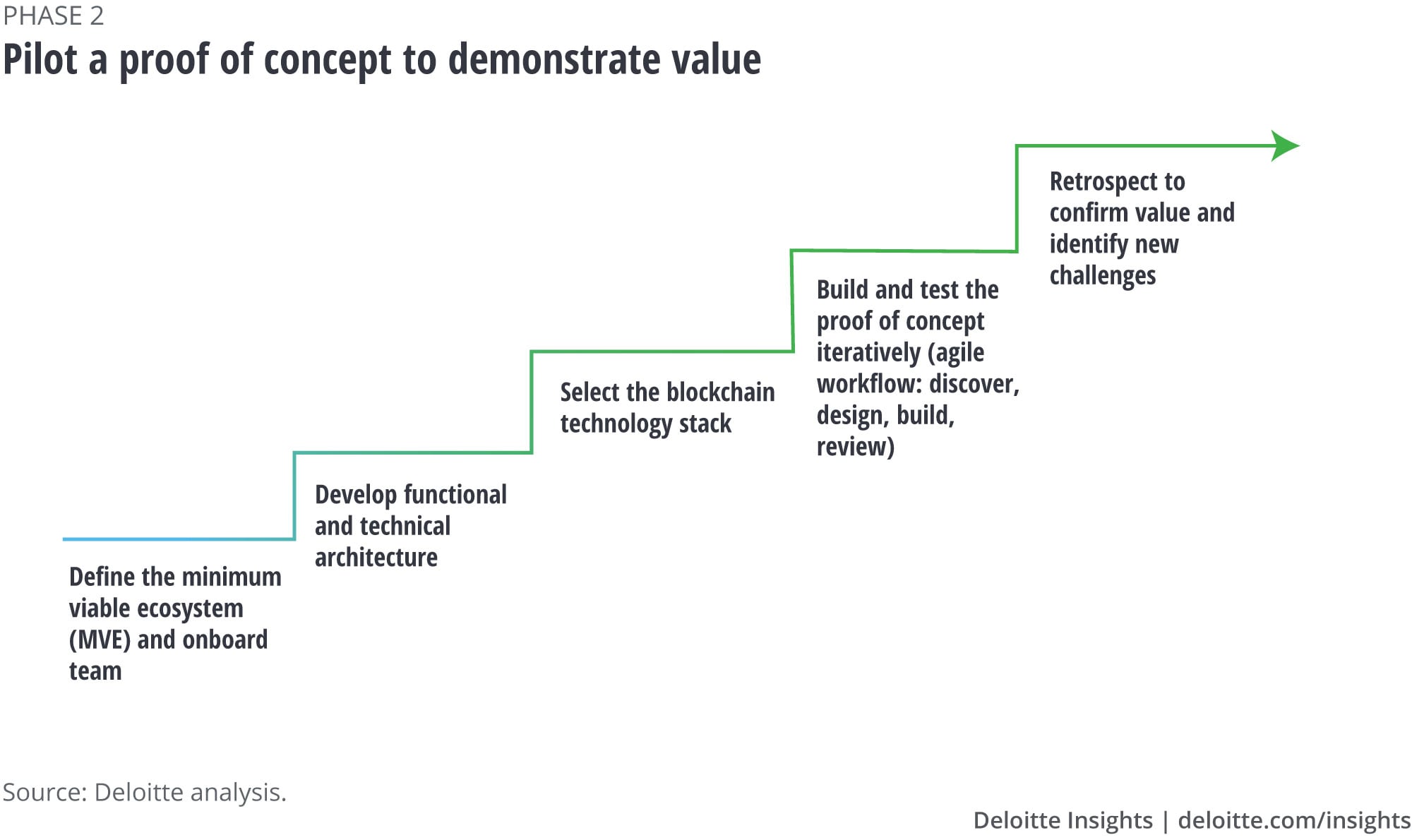

Phase 2: Pilot a proof of concept to demonstrate value

In this phase, a use case is shaped and, importantly, tied to the technical elements required for the solution to be delivered. This phase should create a prototype that can be piloted to prove that the concept works and demonstrates value. Those outcomes are expressed as not only technical success (did it work?) but, more importantly, as value delivered (did we see the anticipated benefit?).

Critical questions to answer for phase 2

- Are all the shared problem’s necessary supply network stakeholders joined by the process?

- Does the functional architecture address the needs of the logisticians and supply network managers who will interact with the solution?

- Does the technical architecture tie cleanly to the asset? What other digital technologies are already in use?

- What specific intermediary technologies are used if a physical asset is involved?

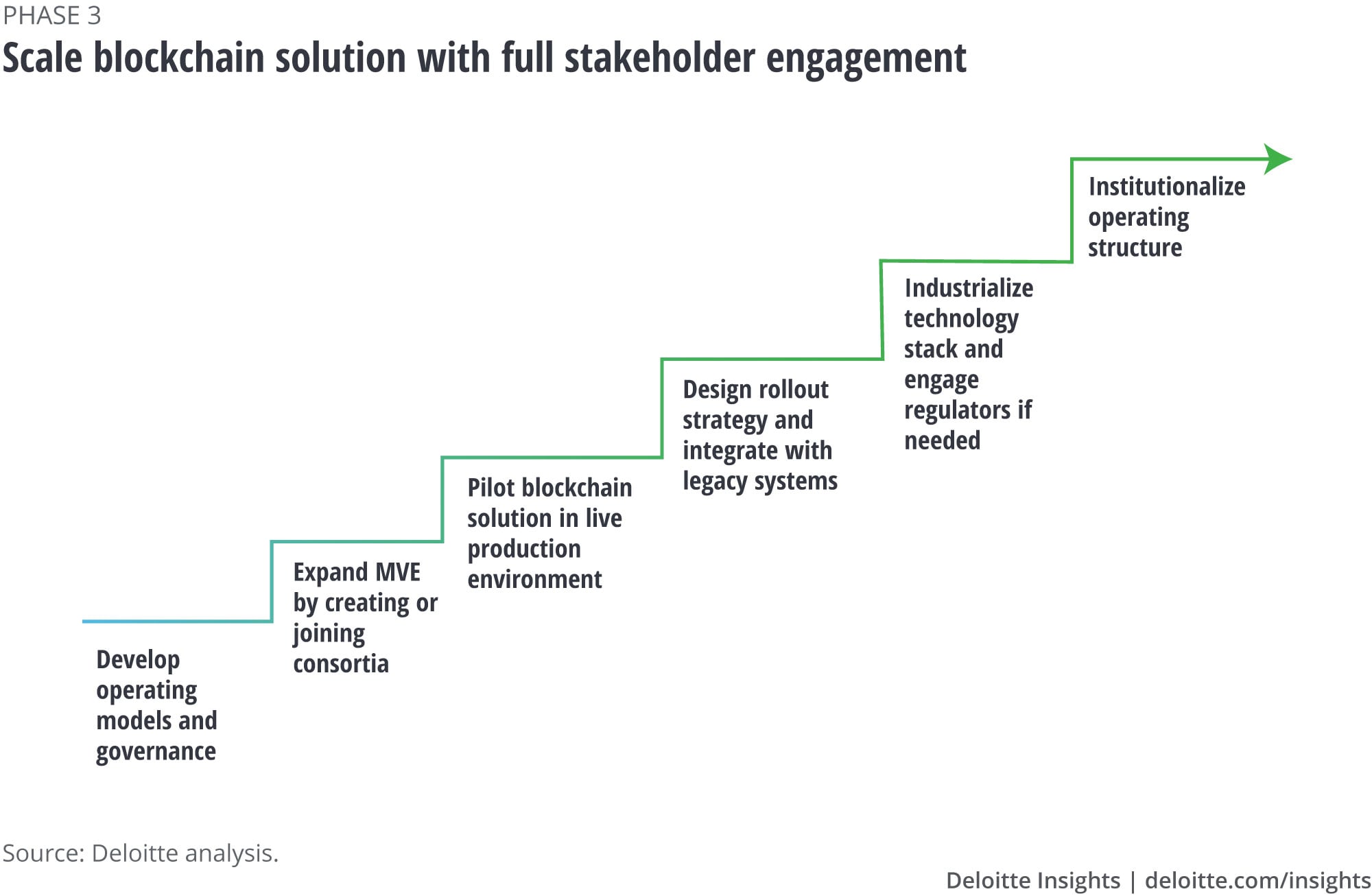

Phase 3: Scale blockchain solution with full stakeholder engagement

Upon demonstration of the value of the solution, critical questions of governance and implementation remain. Often we hear from leaders who, after a successful proof of concept, are ready to start making systems integration decisions. However, for an implementation to be successful, it is critically important that organizations consider operating models and governance. To avoid misunderstandings among stakeholders, teams should answer the key questions of governance, rollout strategy including talent and training implications, consortia formation and management, data ownership, and integration, all before taking a solution live. Such is the case not only because blockchain, like the DSN, is a multistakeholder protocol, but also because stakeholder engagement from the outset may promote shared participation, new business models, and value chains across what can be seen as a common ecosystem. In such fashion, blockchain may incentivize industry players—even direct competitors—to share specific information elements in solving commonly relevant problems while protecting critical IP.15

Critical questions to answer for phase 3

- Do all DSN stakeholders understand each one’s relationship to the asset and the benefit they’ll derive from joining the consortium?

- How will the live production environment rollout be managed in accordance with typical supply network workflow needs?

- What other assets might the solution add value for, and how much overlap between stakeholders is there?

To avoid misunderstandings among stakeholders, teams should answer the key questions of governance, rollout strategy including talent and training implications, consortia formation and management, data ownership, and integration, all before taking a solution live.

Proliferation through organizations and across industry: The road ahead

As the value proposition for blockchain technology within a DSN context comes into focus and successful enterprise adoption stories become commonplace in 2019 and beyond, an accompanying mindset shift needs to take place. As a greater number of assets are brought online, the fundamentals of the scalability of blockchain do not necessarily change, and supply-chain-focused blockchains join with other value chains to create beneficial ripple effects across assets and asset classes.

For example, we can envision a blockchain solution that allows the direct joining of internal finance and supply chain functions with outward-facing vendor or customer-focused interactions, uniting the back office with the rest of the organization via real-time reporting for action. That degree of connectivity itself can create faster closing of the books at end of reporting periods, better cash management, smarter predictive supply ordering, and the ability for finely tuned micropayments and microservice offerings. In shipping, we can envision micropayments being made automatically to a shipping company from a procurer when a physical asset crosses state lines within a specified time frame. Similarly, it is possible that a self-driving truck owned by a distribution firm initiates a micropayment directly to a slower-moving truck ahead of it to allow the first truck to pass in the left lane in a timely fashion.16

With more physical or business event data capturable or quantifiable by digital means, the ability to understand and remove inefficiency in the interactions between products, services, vendors, and others multiplies. Those lowered barriers to connectivity free up space for monetization of existing activities that up until now were not economical to optimize, such as the trucking microtransaction described above.

In this way, blockchain has the potential to become a key part of the industrial grid. Further, with each new supply chain innovation, connectedness will increase through cyberphysical interactions and sensor data, broader Industry 4.0 considerations, and the larger convergence of a wide variety of emerging technologies, including blockchain. Such will ultimately serve to increase supply chain responsiveness and transparency.

Explore the Blockchain collection

-

Capturing value from the smart packaging revolution Article6 years ago

-

Blockchain and the five vectors of progress Article6 years ago

-

Adapting to food labeling laws through blockchain and IoT Article6 years ago

-

Managing risk across the extended enterprise Article6 years ago

-

Assessing blockchain applications for the public sector Article6 years ago