Behavior-first government transformation Putting the people before the process

23 minute read

25 August 2020

Transformation involves changing systems, processes, and organizational structures, but ultimately true transformation is always about changing human behavior. Here’s how government can make it happen.

What makes transformation successful?

Governments are known for moving slowly and at times resisting change. Yet in the face of COVID-19, government has impressively shown it can quickly and effectively implement a new distributed, technology-based operating model, rapidly develop and adopt sweeping new policies, and rapidly adapt in the face of continually changing circumstances.

Learn More

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

This experience might bolster confidence in government’s ability to transform itself. But transformation calls for more than a brief exhibition of novel methods; to be transformative, change has to stick. In some places, we are seeing more questions on “When can government operations return to normal?” than asking “How do we support and sustain valuable elements of this transformation?” Opinions differ in what the appropriate timing should be, but there is a powerful sense that things should return to the prepandemic status quo as soon as it is safe.

This reaffirmation of the old ways of doing things persists while the COVID-19 pandemic is transforming life as we know it, putting citizens at risk, and placing pressure on our health care systems, supply chains, and businesses. The impacts are expected to last for many years, spurring cascading changes in all aspects of life—how we work, study, socialize, and deliver services. To stay ahead of these changes, public sector organizations will need to adapt quickly, truly transforming themselves so they can lead the way through recovery and to a new state of resilience.

So, the recent speed of change in government should not foster false hope. The sweeping, sustained transformation that the COVID-19 era demands can be incredibly complicated and difficult. If you’ve ever made a New Year’s resolution, you know how hard it is to break old habits. Reshaping behavior is even harder at the organizational level, where the prevailing culture and decades-old processes and systems all conspire to reinforce old ways of working, no matter how urgent the need for change.

When experts try to explain why so many transformation initiatives fail, both in the commercial world and at government agencies, they rarely talk about habit or other human factors. It’s much easier to focus on a project’s most expensive, visible, or contentious elements, such as new technologies, process redesign, or changes to the organizational chart. But the human element can be crucial to the success of organizational transformation.

This is true when you’re aiming for transformation with a capital T, such as designing and implementing an entirely new operating model. It’s also true when you’re trying to make some aspects of an existing model work better, or when you’re trying to build a new capability. No matter what kind of change an organization wants to implement, it’s crucial to understand how the proposed changes will affect people as individuals, and what it might take—psychologically, emotionally, or politically—to make them change their behavior. After all, if people keep doing the same things in the same way, what has really been transformed?

Even when leaders understand that they need to encourage behavioral change, they often aim for that goal using strategies without a proven track record. For example, they might offer financial incentives to employees who meet certain performance targets, without clear evidence that this kind of reinforcement works in that context. What if the motivating factors that can overcome inertia in a certain situation have more to do with how employees feel about their work, or how they cohere as a community?

Fortunately, thanks to the work of behavioral psychologists and economists, as well as neuroscientists, we understand much more than we used to about human behavior and its drivers. This work has demonstrated, for example:

- What typically motivates people—a sense of purpose, a sense of autonomy, and the ability to grow in one’s job1

- Why people engage in “predictably irrational” behavior, and how we can harness this understanding to shape and nudge behavior2

- How to use customer analytics and customer experience techniques such as human-centered design to drive workforce experience3

We also know that transparency can help a transformation initiative succeed. By keeping stakeholders informed about all aspects of the effort and inviting feedback, project leaders can gain insights into human motivation and behavior, and how their employees are experiencing the change, as those factors pertain to their particular project. This can help leaders understand which aspects of the transformation are working and which are not, and it helps to build trust among everyone involved.

This is the third part of our series on government transformation post-COVID-19.

“Behavior-first change” applies insights from a range of disciplines including anthropology, behavioral economics, neuroscience, and psychology to better understand and influence human behavior—and governments are beginning to apply it to their transformation initiatives. In fact, with more than 200 behavioral insights units in government worldwide, the public sector has been at the forefront of this movement. So, we’re not proposing a behavioral change approach as something radically new. Instead, we’re suggesting government agencies that might already be applying these techniques externally can systematically apply these insights to their own transformations—whether “capital T” programs or more focused efforts—to improve the chances that these programs will realize their intended outcomes.

More principles for successful transformation

While an understanding of human factors is always crucial, several other themes can be important to a successful transformation (figure 1). The initiative should be:

- Purpose-driven: It inspires the people who will experience the transformation with a sense of purpose and meaning.

- Deliberately designed: It establishes the optimal strategy and business case, putting the right teams and ecosystem in place to achieve the intended results. These elements are made clear and tangible to the project team and stakeholders to drive targeted decision-making and prioritization throughout the project.

- Future-proofed: Participants continuously align intent and execution, anticipating and responding to what customers, the workforce, and stakeholders will need, not just now but in the future.

- Authentically led: Leaders are authentic and accountable, challenging the status quo and leading change within their teams.

- Intentionally delivered: Leaders plan carefully, tailor their delivery, and employ transformation to drive business outcomes and adapt the strategy as necessary.

- Data-driven: Leaders rely on data to inform decisions and validate the course of action before employing the change.

- Sustainably optimized: The organization’s “transformation muscle” is developed, through culture and capabilities, to support ongoing change.

Tapping into what really motivates people

For many years, most workplaces have used the “carrot and stick” approach to motivate employees. Do a great job, and you’ll reap a reward—a promotion or a favorable assignment. Do a bad job, and you’ll be punished—passed over for promotion, stuck with undesirable assignments, maybe even fired.

That method may have a long tradition behind it, but it’s not the one we need today, says business author Daniel Pink. According to Pink, extrinsic motivation—the promise of reward or punishment—works only for employees who perform simple, routine tasks. For most employees in the 21st century workplace—the ones whose success requires initiative, creativity, and independent judgment—intrinsic incentives do a much better job.4

Intrinsic incentives are motivators that work from within, spurring employees to perform great work for the sake of personal fulfillment. Pink shows how intrinsic motivation comes in three varieties:

- Purpose: The employee’s sense that work has meaning: Do it well, and you could make a real, positive difference—for the work unit, larger organization, community, or the world at large.

- Autonomy: The ability to direct one’s own work. If employees control when, where, how, and with whom they work, they feel more deeply engaged and are more likely to innovate.

- Mastery: The sense that the employee is learning, growing, and improving. People who continually master new skills feel powerful; their jobs are interesting, and they look forward to going to work.5

ReImagine HHS

One example of purpose working as a transformation motivator is ReImagine HHS, an enterprisewide strategic planning and transformation initiative launched by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in April 2017. To define the purpose of ReImagine HHS, transformation leaders focused on outlining a future-state vision—making the department’s operations more efficient and effective, and improving customer service—to staff and communicate a clear, mission-focused "why" for their efforts.

From the start, leaders worked to make participants feel that they were all working toward the same end. Career staff from all of the department’s 25 divisions took part in the initiative, starting with an ideation session that convened more than 200 employees to discuss potential solutions.

Although many expected the career civil servants and political appointees to form separate camps, an exercise conducted during the ideation session revealed that the two groups largely agreed on their goals for the program. One of the themes that emerged was that, despite disparate missions across the different departments and agencies, there was a strong need to support decision-making and planning with data—and so a priority emerged to invest in data analytics and reporting across the enterprise. Based on this ideation, HHS developed a list of six strategic shifts intended to transform the department’s operations and culture.6

This exercise created a sense of cohesion that has nourished the entire initiative in the months and years since its launch. As employees developed pieces of the strategy and then started to execute that plan, their common sense of purpose convinced them that ReImagine HHS was their program—not simply another initiative du jour imposed from on high. This sense of ownership grew so strong that even when the political appointee leadership changed in 2018, ReImagine HHS kept moving toward its goals.

Similarly, leaders of any transformation initiative who want to motivate employees throughout the organization should clearly define the “why.” Employees should see a clear link between the concrete steps required to accomplish change and a compelling, mission-centric goal. This purpose-based motivation will be more powerful if people at multiple levels in the organization are involved from the very start in finding or creating that link between the overarching vision and work at every level.

As employees developed pieces of the strategy, and then started to execute that plan, their common sense of purpose convinced them that ReImagine HHS was their program—not simply another initiative du jour imposed from on high.

IRS’ modernization

Traditional management takes a top-down approach: Leaders determine how an organization will operate, what employees do, when and where they do it, and what tools they use. According to Pink, though, employees produce much more value when they can decide how best to accomplish their own work.7

While a large transformation requires executive leadership and support, a successful effort also needs significant input from all levels of the organization. Instead of making detailed plans and giving directives, top leadership can take a new role: enabling and supporting the efforts of grassroots participants.

When the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) launched an ambitious modernization initiative, for example, much of the energy behind that effort came from rank-and-file teams that devised and executed their own solutions. Unlike other organizations engaged in transformation initiatives, the IRS did not receive a mandate to transform its tax administration, nor did it receive the funding and resources an agency typically needs to support a sweeping change initiative. But, along with facing aging infrastructure and shrinking resources, leaders understood that to deliver the level of service that citizens demand today, the IRS needed to modernize its information systems and make its operations simpler, more efficient, and more customer-centric.8

In response, the IRS developed a plan that focused on improvements in four critical areas: taxpayer experience, core taxpayer services and enforcement, IRS operations, and cybersecurity and data protection.9 Inspired by these efforts at the enterprise level, many units within IRS launched initiatives of their own, developing new concepts of how the system would operate, creating new strategic planning offices, and otherwise investing in their own strategic change capabilities.

For example, the income tax team, Wage and Investment, got involved early by examining the agency’s CONOPS and designing a new one. Team members looked at their end-to-end process to define potential improvements. Then they executed an improvement plan.

Transformation programs that stem from a peer-to-peer need to change the organization can develop great staying power. That can be especially true when leaders give the people who want the change, the space and autonomy to develop solutions and put them into action. Moreover, a decentralized approach to managing change typically works best when each leader involved in strategic planning can determine how best to use his or her agency’s capabilities and has ownership of the outcomes.

Designing environments that better enable and empower humans

Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book Nudge introduced the powerful concept of choice architecture: the idea that subtle tweaks to choice environments can significantly impact our decisions. By designing choice environments in ways that work in harmony with human psychology, we can prompt better decisions that harness the predictable irrationality that arises from our cognitive limitations.10

A key element of behavioral science is the use of choice architecture and other techniques to try to influence the choices people make. It turns out that our “decisions” are often the result of subconscious, nonrational influences. If the default option for our 401(k) is to invest, we are more likely to save for retirement. If we know our neighbors are recycling, we are more likely to recycle.

Behavioral science combines insights from psychology, anthropology, economics, and neuroscience to explain how people choose to act under specific circumstances. More than six decades of research in the field reveals that people often act irrationally, despite their best efforts to do the opposite. This holds true for program designers as well. By not putting the end user first, they often design programs in a manner that fails to resonate with how the human mind works.11

Government agencies have been in the vanguard of the behavioral science movement, testing nudge theories in hundreds of real-life settings around the world.12 And behavioral science appears to be particularly useful in getting employees to adopt new technologies that can improve efficiency and effectiveness in an organization.

In most cases, adopting a new technology requires that people change their habits and behaviors—something that isn’t always easy to accomplish. Many government projects aiming to digitize operations and services struggle with user adoption because they don’t adequately consider user needs throughout the development process. In particular, they often fail to consider how people actually think and act.

A number of behavioral science themes contribute to technology rejection among government employees and the citizens and businesses they are trying to serve:13

- Cognitive overload: We live in a fast-paced, constantly changing environment. With finite physical and cognitive resources, give people too much to consider, and they will often forgo specific steps and tasks, often unconsciously.

- Black boxes: When leaders fail to communicate to employees why a change has been made, employees are less likely to see the value of working in a new way. Similarly, if their buy-in is not considered, the entire change may run counter to how employees conduct their work effectively. Also, if they do not perceive a positive result, it may feel like the action is not worth doing. How can leaders overcome this problem? Stories. From the Bible to the Quran to ancient Greek myths, stories have had immense power to influence human psychology and behavior.

- The power of inertia: Behavioral insights reveal that people usually take the path of least resistance.14 In most cases, we stick to the behavior and habits we have already developed. For technology adoption, in the short term, it’s easier to adhere to the old way of doing things than it is to learn a new method. Richard Thaler offers a powerful way to overcome this challenge: “If you want people to do something, make it easy.”15

A number of strategies from behavioral science can help overcome these challenges. First, give workers the opportunity to personalize the new approach to their current way of working. This not only can help initial buy-in but can lead to more staying power of the new behavior.16 Second, give employees the opportunity to trial the new way before it’s fully rolled out. Third, find ways to lower the perceived risk (performance, financial, safety, psychological) of making the change.17

Adopting a new technology requires that people change their habits and behaviors—something that isn’t always easy to accomplish.

How behavioral science helped an agency eliminate a six-month backlog

Most states provide several avenues for citizens to apply for state-sponsored benefits programs. For programs ranging from unemployment insurance to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), applicants rely on quick and timely processing to determine their eligibility.

While they could apply online, many people still prefer to fill out paper applications. In these cases, state employees have to convert that paper into electronic information. But with such a large variety of both benefits programs available and households applying, entering this information requires a great deal of labor and mental effort.

With more than a dozen different programs that require eligibility determination, one state human services agency accumulated a six-month backlog of paper applications that needed to be entered into its information system. To address this problem, the agency leadership team used predictive algorithms to forecast how many backlogs it could expect in the coming weeks, days, and even hours. Leaders then adjusted staff accordingly and, at especially busy times, supplemented regular employees with temporary workers.

To address the cognitive overload issue, managers built profiles that highlighted which kinds of issues each worker was most efficient at resolving. They then rearranged the choice architecture of the employee work environment in two major ways:

- A list of 10: Each employee received a personal list of 10 backlogs to resolve each day. Since these lists were tailored to each worker’s specific strengths, employees no longer suffered cognitive overload, and they lost far less time in switching from one type of benefits application to another.

- Agile adjustments: As needs changed, so did task assignments. Work lists could be adjusted every two hours when needed. They could also change based on how quickly or how well a worker was getting through his or her assigned list.

In addition, program leaders rearranged the agency’s incentives system to place value on a more meaningful metric. Before, workers gained rewards based on how many backlogs they had resolved. Now, leaders tracked and rewarded employees based on the number of citizens they helped. This change produced two improvements: It discouraged employees from working only on the easier backlogs, and it more directly connected employees to the people they served. Managers also used data analytics to produce large aggregate dashboards that were updated in real time with the number of citizens the employees had helped in each program.

Thanks to these changes, employees gained a more agile and transparent environment where they could see the value they brought to their state in their work. Within 10 weeks, the state had completely eliminated six months of backlogs while also increasing employee morale and providing a greater sense of purpose.

To address the cognitive overload issue, managers built profiles that highlighted which kinds of issues each worker was most efficient at resolving.

When technology-based transformations fail, the reasons often have less to do with the technology itself than with the behavioral hurdles that keep people from willingly undertaking new action. These hurdles can be overcome. Government program administrators can kindle buy-in by leveraging behavioral science–based design principles that put human considerations before technology.

Unlocking insights into workforce experience using human-centered design

Every organization is composed of individuals. When you implement change in an organization, you alter certain aspects of those individual human lives. Transformation interrupts long-standing routines, pushing people to use new processes and tools. It might rearrange employees’ daily working lives, giving them different colleagues, supervisors, and responsibilities. It might change the way they’re rewarded for their efforts. People who work in different roles will experience the change differently. A person’s temperament and personal needs could also influence what the change feels like to that individual. According to an American Psychological Association 2017 work and well-being survey, workers experiencing recent organizational changes were more likely to report chronic work stress than employees who didn’t experience changes (55% vs. 22%). Employees experiencing change also reported feeling more cynical and negative toward others during the workday than those who didn’t (35% vs. 11%).18

An individual’s experience of change will help to determine how well that person embraces the new program. If change makes employees’ lives more difficult, or if it arrives with no explanation of how the transformation will help employees and support the organization’s mission, they are likely to resist. But if employees understand how the change will benefit them in the long term, even if the disruption feels uncomfortable at first, they might become strong advocates.

If change makes employees’ lives more difficult, or if it arrives with no explanation of how the transformation will help employees and support the organization’s mission, they are likely to resist.

That’s why it’s important to consider human experience in a transformation initiative. Designers should approach the project with empathy, engaging directly with the impacted employees or getting into their minds as much as possible, so they can create the program with stakeholders’ wants, needs, goals, and values in mind. Designers should also try to understand and address the cognitive biases that might prevent some individuals from making the behavioral shift needed to support the transformation.

While discovery research with the leaders helps in framing the challenge, ethnographic research—studying people in their natural environment—helps in understanding employees deeply and why they behave the way they do.19 Using insights gained from this research and from behavioral science, designers can create the right nudges to drive the change they seek. They can also use those insights to craft communications and resources that will resonate with employees and other stakeholders, naturally getting their support for the transformation initiative.

When commercial organizations are trying to spur change—such as improving their product assortments or increasing sales—they often conduct research to understand the customer experience. As part of that work, they use factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, or geography to divide the customer base into meaningful segments. The goal is to understand what different groups want and need from their products, and what it’s like for the people in each group to use those products. A 22-year-old, single, African American woman in Brooklyn could have different values in mind when she shops for jeans than does a 60-year-old, married, Mexican-American woman in Tucson.

As an organization plans for a major transformation, it can do similar research into the workforce experience. And as it designs strategies for communicating the upcoming changes to employees, it can use a segmentation approach. That doesn’t mean, for example, simply tailoring the message differently for people who work in different departments. It means moving away from merely executing change processes to designing change experiences for the people involved. For example, will some departments be split up and their members reassigned, while others stay put but will need to start using a complex new software suite? The change will look very different to members of those two groups, and program leaders should communicate with them accordingly.

Cyber safety awareness at the NIH

As part of a large program called Optimize NIH, the National Institutes of Health launched an initiative called Optimize IT Security, part of which was a communications campaign to increase NIH stakeholders’ awareness of cyber safety.

As part of the campaign, the NIH conducted work in four phases:

1. Discover: Researchers conducted interviews with key stakeholders to learn about their need for a cyber safety awareness campaign. They also crowdsourced ideas for the campaign from a larger number of employees. This information helped the design team develop a compelling message about the danger of cyberattacks and why people across the organization need to pay better attention to cyber safety.

The team then divided the population at the NIH into stakeholder groups and, for each group, developed a set of personas corresponding to people in that group.

2. Define: For each persona, researchers developed a journey map, defining all the changes of thought and experience those people would experience as they passed through the stages of change readiness: awareness, understanding, knowledge, adoption, and commitment.

Then the team mapped the stakeholder groups based on two factors—their level of risk, defined by their access to data and their public profiles, and their potential to drive cyber-safe behavior in other groups.

3. Develop: Based on information developed in the discover and define phases, the team made recommendations about how to structure the cyber safety awareness campaign. They suggested that the campaign should be personal, focusing on individual stories and real-life cyber risks; leadership-led, engaging leadership as change makers to drive change at all levels; evidence-based, leveraging global cyber safety metrics and trends; engaging, inviting participation, adoption, and collaboration across the NIH; inclusive, encouraging accountability for cyber safety across all levels and disciplines; and sustainable, promoting enduring change in the larger organization.

4. Deliver: The team delivered several communications products for the campaign and engaged the NIH team in determining the products’ prioritization. After that, the team also developed a plan to monitor and continuously evaluate the campaign so that the changes would be anchored sustainably.

When designers consider the employee experience or codesign solutions with them, employees are more likely to support the transformation because they find it beneficial to participate in the new system, program, or process. As program leaders explain the transformation initiative to employees, they should communicate with empathy, using messages tailored to the experiences of different groups. They also should develop incentives, rewarding members of different groups for accepting any initial inconvenience or discomfort they might feel as change takes hold.

When designers consider the employee experience, employees are more likely to support the transformation, because they find it beneficial to participate in the new system, program, or process.

Transparency as an enabler of change

The most successful transformation teams share results throughout the transformation process—even when something isn’t working. Transparency can be a powerful motivational tool because positive momentum builds on itself, while the sharing of lessons learned can improve efforts on other workstreams. Regular reporting also gives the transformation team information about what is and isn’t working, allowing team members to make real-time adjustments. When a team reports its progress toward shared goals internally, those efforts will probably focus on day-to-day status changes. When the team shares its results far beyond its immediate members, often a picture of larger changes and the value of the overall effort will emerge. Behavioral science work shows the importance of communicability and observability: innovations that are observable diffuse more rapidly. If it is an unobservable innovation, then communication is key to enable people to support the change.20

As a team reports its activities and their results, it soon becomes clear whether people have been encouraged to change their habits, or whether the team needs to keep searching for the right motivation. Transparency can also reveal whether particular efforts to nudge people into new behaviors are working, or if it will take a different kind of nudge to spark the right kind of change. In addition, feedback from stakeholders may quickly reveal whether the transformation plan is properly addressing the experiences of various stakeholder groups. When the transformation team provides project updates, that helps team members—as well as colleagues not enmeshed in the day-to-day running of the program—appreciate the group’s achievements and celebrate its progress. Based on information in these reports, the team can continuously refine its approach to transformation, doubling down on tactics that have proven useful and rethinking tactics that have not. Such flexibility can help avert the change fatigue that often hits staff in organizations that pursue change over and over with varying results.

The Marine Corps reengineers its rifle squad

Throughout its 244-year history, the US Marine Corps (MC) has always stood ready to change and adapt. But the recent reorganization of its rifle squad structure represented an unusually big leap forward.

The rifle squad, traditionally a group of 13 individuals with precise roles to play in combat, has been central to all the operations of the MC since the 1950s. As new technologies have emerged, the MC has given the squad new equipment, but it has not changed the legacy structure. For decades, the squads required a relatively constant and predictable flow of munitions to support three automatic weapons in the field.

In recent years, however, the MC’s clear mission—supporting the war fighter in the theater of battle—has driven the enabling areas to change their systems and rewrite old habits. As a result, the MC has totally reorganized the rifle squad, bringing the number to 15 by adding an assistant squad leader and a squad systems operator. It has also assigned the squad new gear, including a small quadcopter drone—the first to be used at the squad level—new night vision devices, and new grenade launchers. The new structure quadrupled the number of automatic rifles, requiring the MC to institute new ordering procedures, munitions volumes, and maintenance schedules. These dramatic changes in staffing and equipment created a need—and an opportunity—to make similar transformations in areas of the MC that provide support to the rifle squad.

The MC didn’t make changes based simply on discussions of new ideas; it conducted experiments to learn which ideas produced the best results. To test its concept for redesigning the rifle squad, along with other potential changes, the MC assigned an entire battalion to operate as an experimental team. While carrying out all of their regular duties, members of that battalion also implemented new ideas and deployed new technologies, providing feedback to the MC Warfighting Lab on ideas and technologies that worked well, those that might work better with some modification, and those that seemed to offer no benefit.

Because the experimental battalion works in public, and members continuously interact with their peers, the results of these experiments are completely transparent. Everyone can see how well each idea works out and can base future decisions on data that emerges from the tests.

The Marine Corps didn’t make changes based simply on discussions of new ideas; it conducted experiments to learn which ideas produced the best results.

When an organization changes and tests operational procedures in full view of everyone concerned, people learn and share knowledge more quickly. This practice builds trust in the current attempt while ensuring that the next attempt will bring even more improvement.

Making it happen

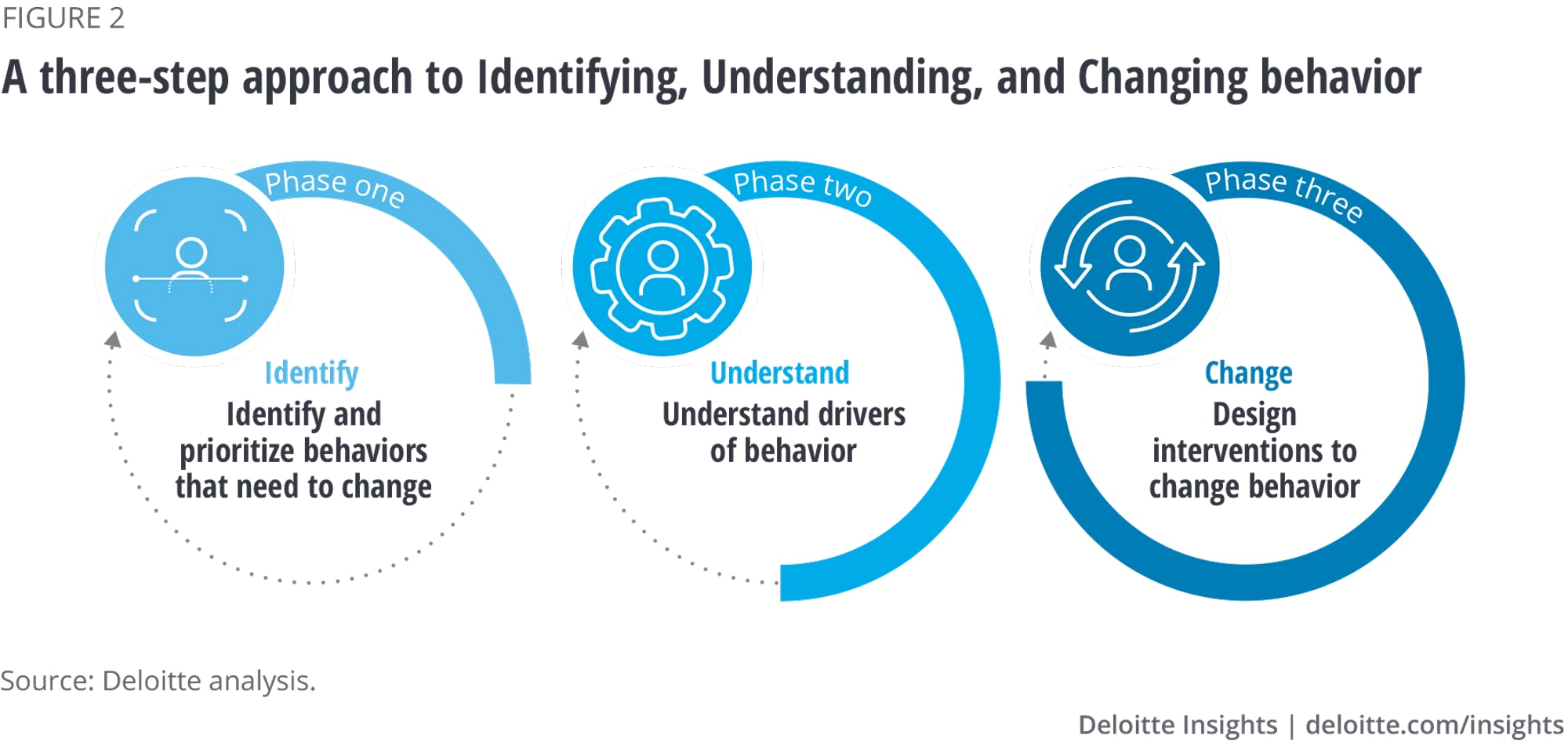

A behavioral insights approach (figure 2) focuses on identifying current and target behavior, understanding behavioral drivers, analyzing the barriers and enablers to behavioral change, designing targeted interventions, and understanding which interventions could make the most difference by testing and evaluating them. The interventions can range from changing incentives to using more complex techniques drawn from behavioral economics and psychology.

Phase 1: Identify

Identification of desired target behaviors is an important first step toward behavioral transformation. This can be broken down to a list of precise behaviors and should be defined using the 5Ws framework (Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?) to ensure they are tangible and specific enough to change. For example, “increasing retirement savings of a household” is top-line target behavior and can be decomposed to precise behaviors such as “opening a new retirement account” or “setting aside more money per month.” The identification exercise then leads to prioritizing these behaviors and assessing the current behaviors against these goals.

Phase 2: Understand

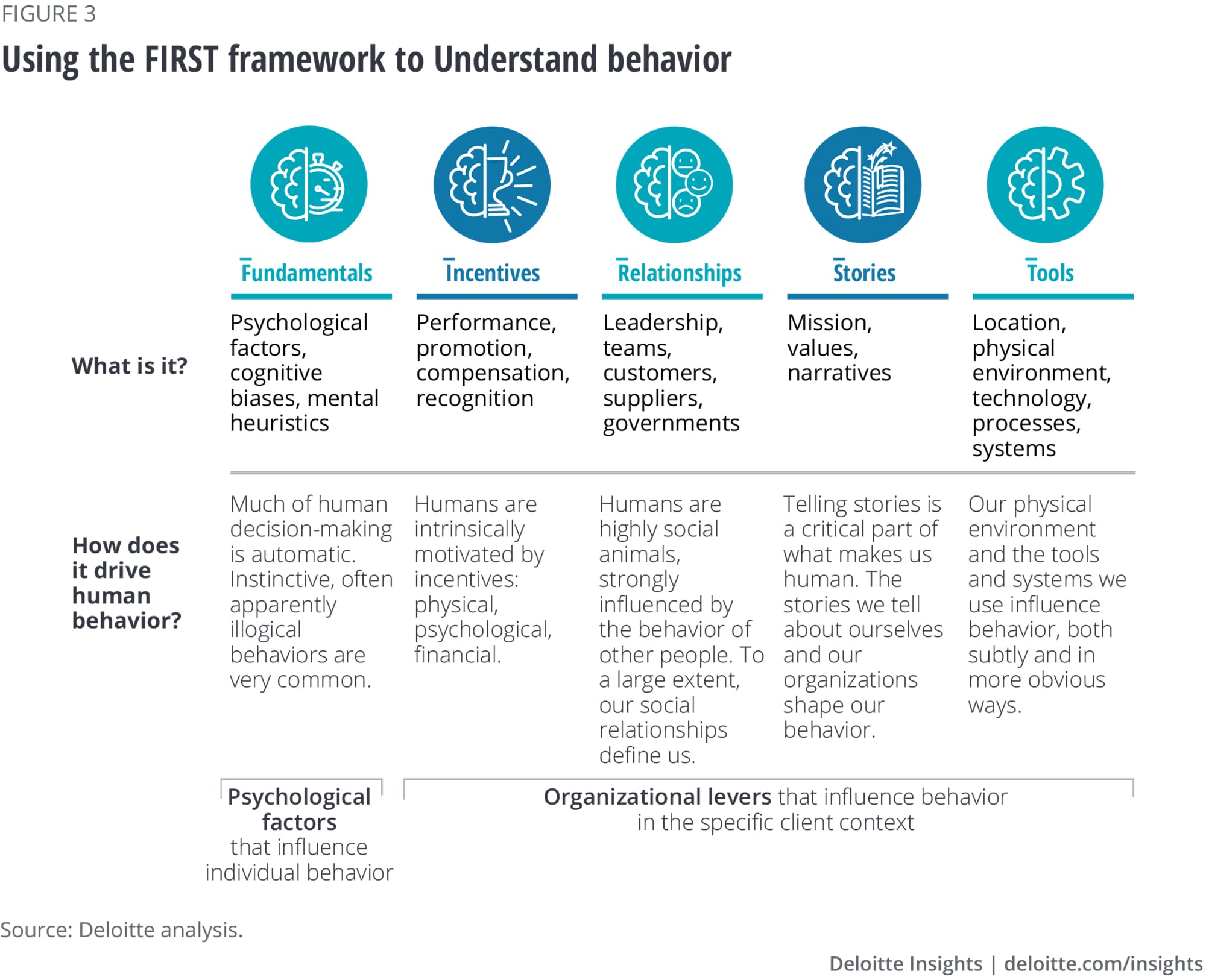

The FIRST framework (figure 3) can then be applied to understand behavior by analyzing the common drivers. The fundamentals lie in examining the psychological factors and cognitive biases that make much of individual decision-making automatic. Incentives, relationships, stories, and tools can be useful in facilitating conversations with appropriate stakeholders around shifting organizational levers, taking into account the consequence of these changes.

Phase 3: Change

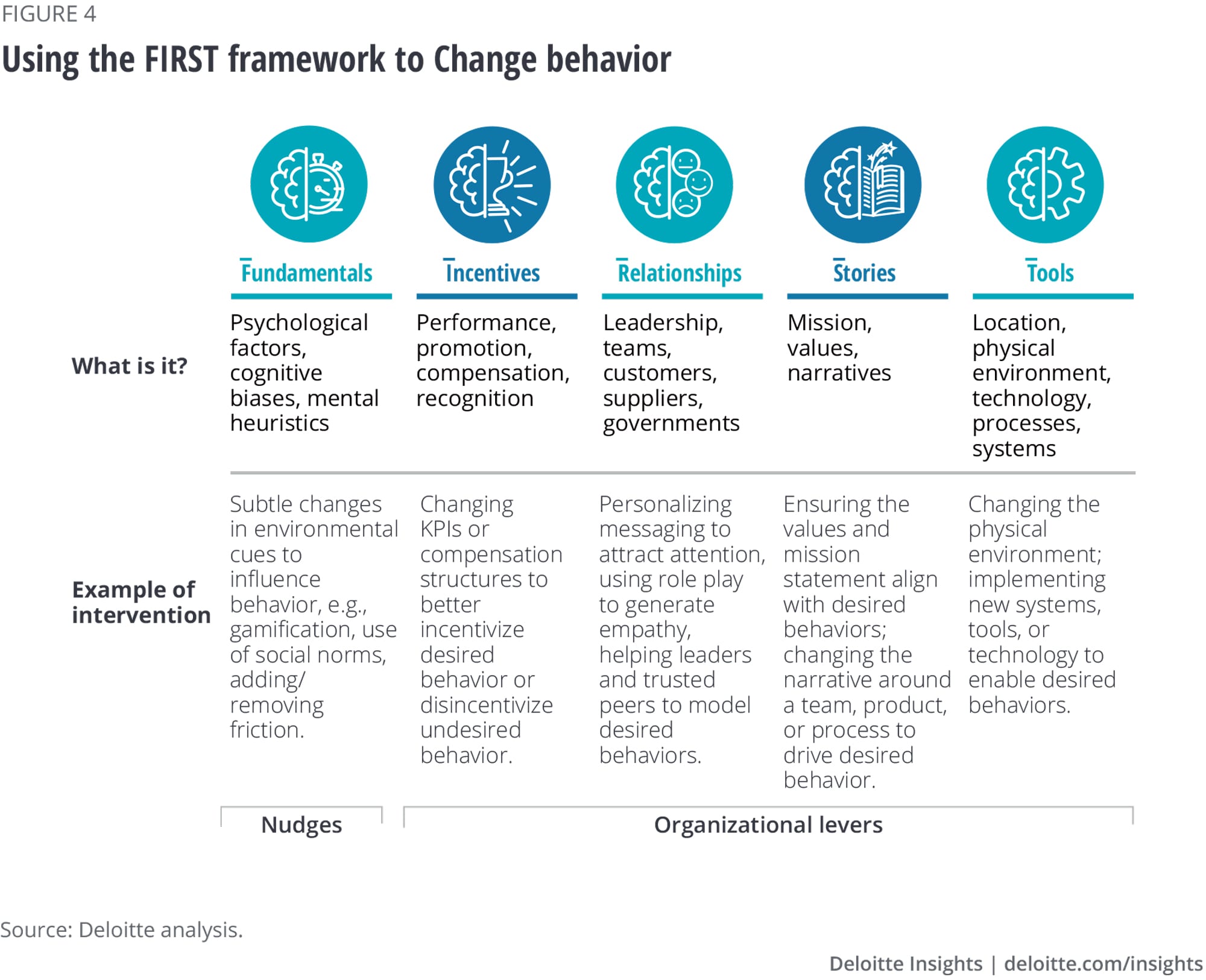

The outputs of the understand phase are then used to design behavioral interventions such as nudges, gamification, and organizational levers to shift to target behaviors (figure 4).

Transformation to get to thrive

An organization is not an optimized machine, but a complex, adaptive ecosystem. When one area makes a change, other areas throughout the organization may also have to change in order to keep the whole system operating smoothly. But organizations can’t change without convincing their people to also change and adopt behaviors that will support the larger organizational transformational efforts.

Because the components of an organization are so complex and interrelated, organizational transformation is never a “one-and-done” endeavor. After the initial transformation, the changes require ongoing management. It’s not enough to track the results; it’s also important to continually evaluate the results and make adjustments. As government organizations respond to COVID-19, the changes they put in place today will influence how well they navigate the eventual recovery, in terms of both human health and the economy. Successful changes made now can also position organizations to thrive in the longer term. Using transformational strategies that account for human behavior, government organizations can lay the foundation for greater resiliency far into the future.

Explore more COVID-19 content

-

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

The heart of resilient leadership: Responding to COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

Governments’ response to COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

New architectures of resilience Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 insights Collection

.jpg)

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.231.231.desktop.jpeg)