Why is the housing sector booming during COVID-19? Economics Spotlight, November 2020

7 minute read

21 November 2020

Housing demand has been robust amid the pandemic due to high-wage remote workers’ continued strong economic positions, low mortgage rates, and millennials entering the prime homebuying age. That said, many renters and homeowners who lost their jobs risk becoming homeless.

The US economy posted record-breaking growth in Q3 as restrictions lifted and consumers and businesses reignited their spending and investment. Yet even with this growth, the economy remains smaller than at the end of 2019. Subsequent quarters are likely to be challenging as infection caseloads rise and states face the possibility of reintroducing restrictions. One sector that has been resilient through the downturn and is likely to remain so amid the ongoing recovery is housing. Housing permits and starts have returned to trend and are likely to grow further in response to the sharp acceleration in home sales since the middle of Q2.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Apart from the fact that buyers and sellers have found ways to navigate through the restrictions of the pandemic, a few factors have combined to boost housing demand. These include the continued strong economic positions of high-wage remote workers, historically low mortgage rates, and more millennials moving into prime homebuying age. Yet there are risks—the housing sector’s strong performance could be derailed by a resurgence in the pandemic and a continued thinning of housing inventory.

Furthermore, unequal impact of the pandemic has led to a dichotomy in the housing sector where although housing demand is robust among those whose jobs are less at risk, there are millions of renters and homeowners who have lost their jobs and risk facing eviction and foreclosure.1 As the economic recovery progresses, policymakers might soon be dealing with the myriad of issues that come with increased homelessness.

1. High-wage workers are driving housing demand

High-wage workers—workers who fall into the upper half of the income distribution—have been relatively unscathed during the pandemic. This is primarily because of the greater likelihood that they are employed in industries and have occupations where remote work is possible. Job security, negligible impact on income, and reduced spending on services due to the pandemic have left them with more money to spend on housing. Moreover, these workers are more likely to be current homeowners and are, therefore, more likely to benefit from rising home prices. This increased equity has allowed them to upgrade to bigger homes or to buy second homes. Finally, the likelihood that remote working will persist is driving demand for more spacious homes, and telecommuting is opening more affordable options to potential homebuyers who can now widen their search farther away from the workplace.

High-wage workers have escaped the pandemic’s economic impact and have more money to spend on housing

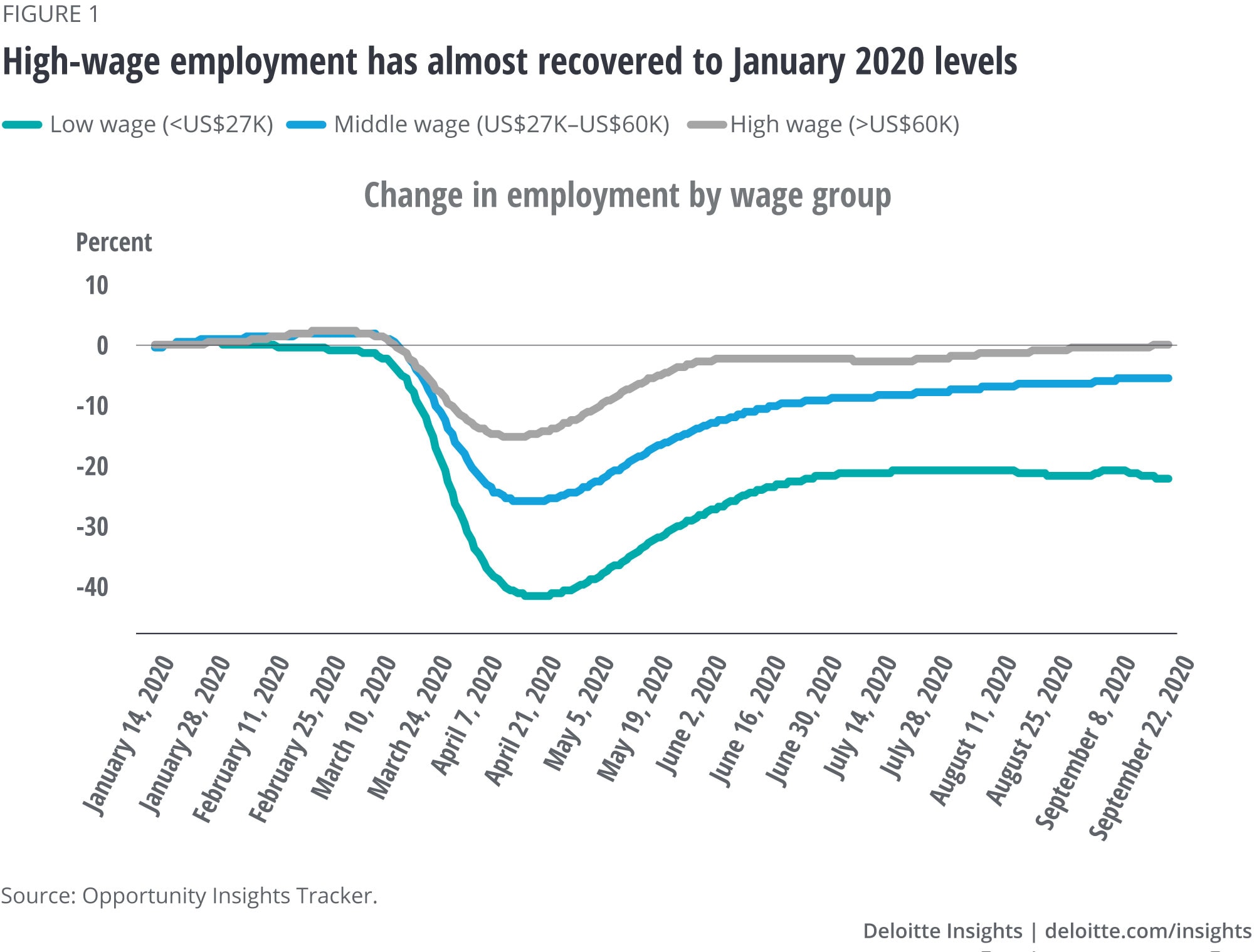

Data from the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker shows that by the end of September, employment among workers who fall into the upper half of the income distribution (roughly those who earn above US$60,000 a year) had almost recovered to its January 2020 level (figure 1).2 These workers are more likely to be employed in industries such as finance or professional and business services in which it is possible to work remotely without a loss of productivity or income. The economic impact of the pandemic has been disproportionately borne by workers who make up the lowest quartile in the income distribution (roughly those earning less than US$27,000 a year).3 Low-wage workers are more likely to be employed in high-contact service industries, such as leisure and hospitality, which have found it hard to generate demand as consumers choose to stay away.

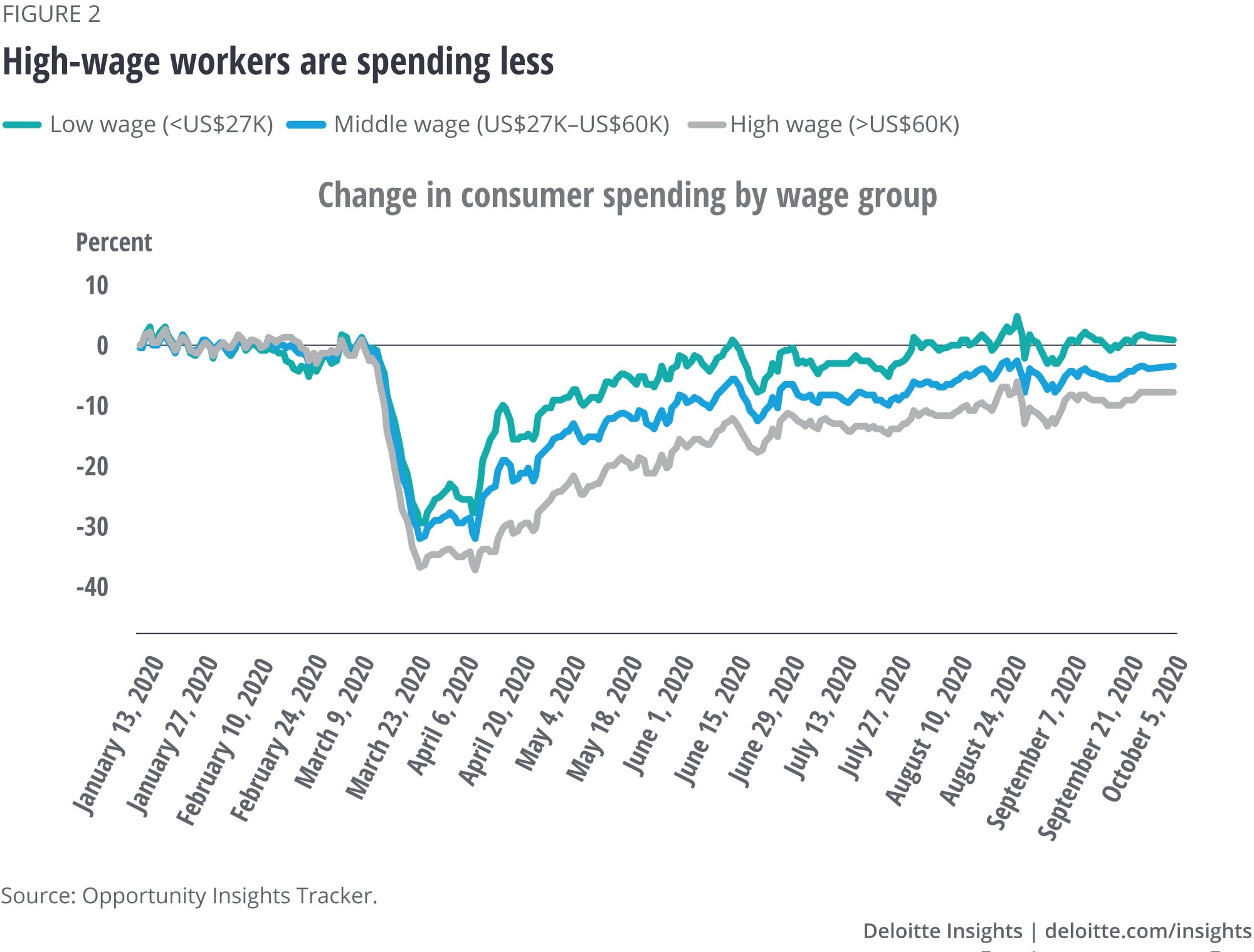

Data from the tracker also shows that high-wage workers were spending 7.5% less in mid-October than they did in January (figure 2).4 The lower spending is more than accounted for by a reduction in spending on services. Overall consumer spending in Q3 was a little more than 3% lower than at the end of 2019 because increased spending on goods was more than counterbalanced by decreased spending on services that account for roughly 65% of all consumer spending. This pattern leaves high-wage earners with more money to spend on big-ticket purchases such as home improvement, or in some cases, new housing.

Rising home equity is an additional benefit to high-wage workers

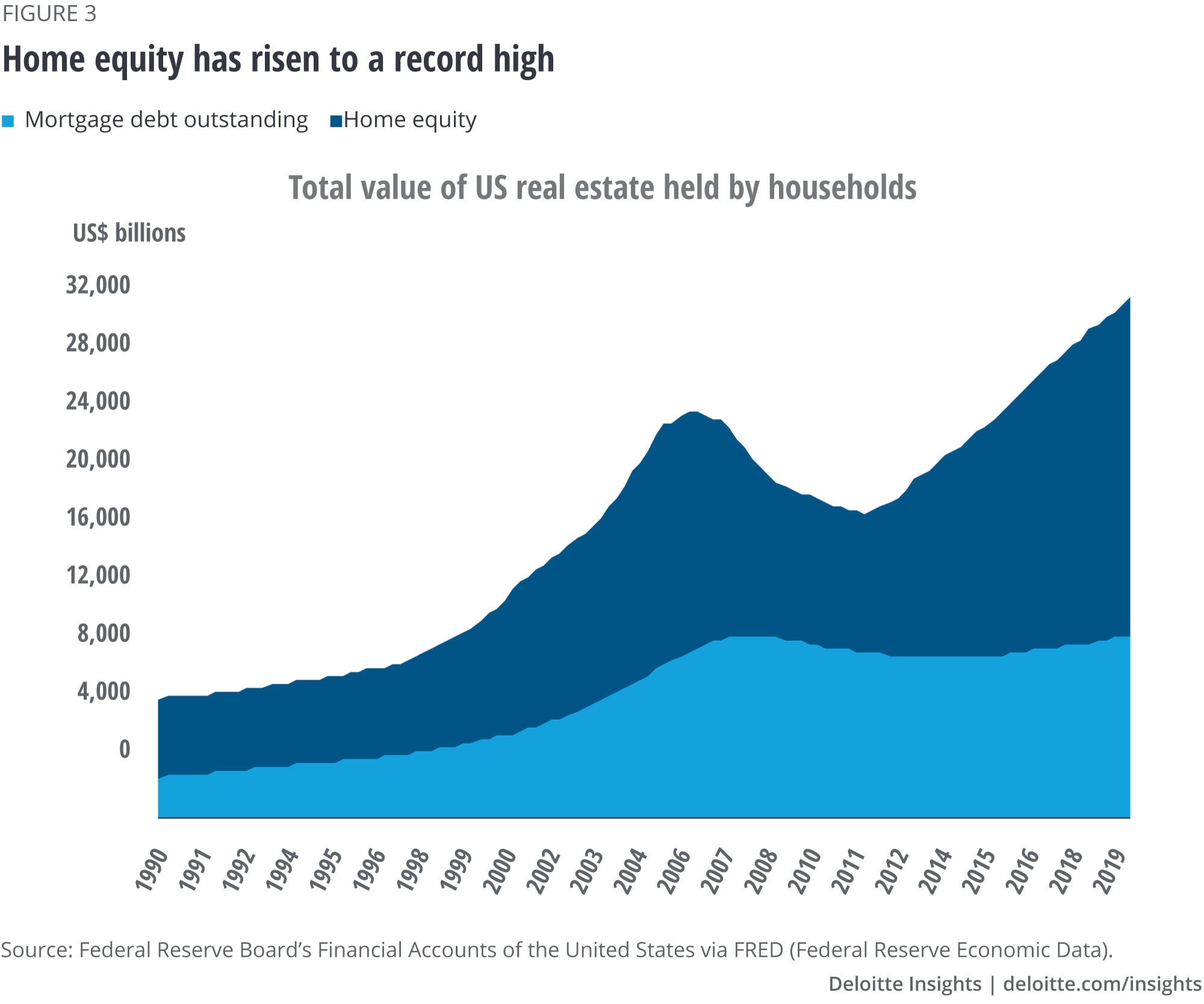

High-wage workers are also more likely to be homeowners. Four out of five households in the upper half of the income distribution own houses.5 Strong demand for housing and a shortage of housing inventory have sent nominal home prices higher. While this blunts affordability, especially for first-time homebuyers, it builds equity for existing homeowners (figure 3). Record-high levels of home equity allow high-wage remote-working homeowners the opportunity to upgrade to a bigger home or buy a second home.

Continued remote working is likely to increase the demand for space; telecommuting widens the options

A University of Chicago research paper found that 37% of jobs in the United States can be done entirely at home.6 It is highly likely that most of the workers in such jobs fall into the upper half of the income distribution. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates that the share of working days spent at home by full-time workers is likely to triple after the pandemic relative to pre-pandemic levels.7 Remote working is likely to boost the need for more space as houses become common arenas for living, working, and recreation. This has resulted in greater demand for bigger homes. The demand for more space is reflected in the outsized growth in larger mortgages.8 Moreover, the falling value of proximity to the workplace is likely to allow homebuyers to widen their housing search. High-wage city renters could become suburban homeowners or even choose to move to more affordable homes in smaller cities.

2. Mortgage rates are down, and affordability has trended up

The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy response to the pandemic as well as its revised approach to inflation means that short-term interest rates are likely to stay low until at least the end of 2023. The Fed is also keeping long-term interest rates low. Since March 2020, the Fed has purchased mortgage-backed securities at the fastest pace since initiating quantitative easing as a monetary policy tool in 2008.9 The Fed’s response to the pandemic has dropped 30-year fixed mortgage rates, which were already trending down since the 1980s, to historical lows (figure 4). This is arguably the strongest tailwind for the housing sector and is beneficial to both existing homeowners and new homebuyers.

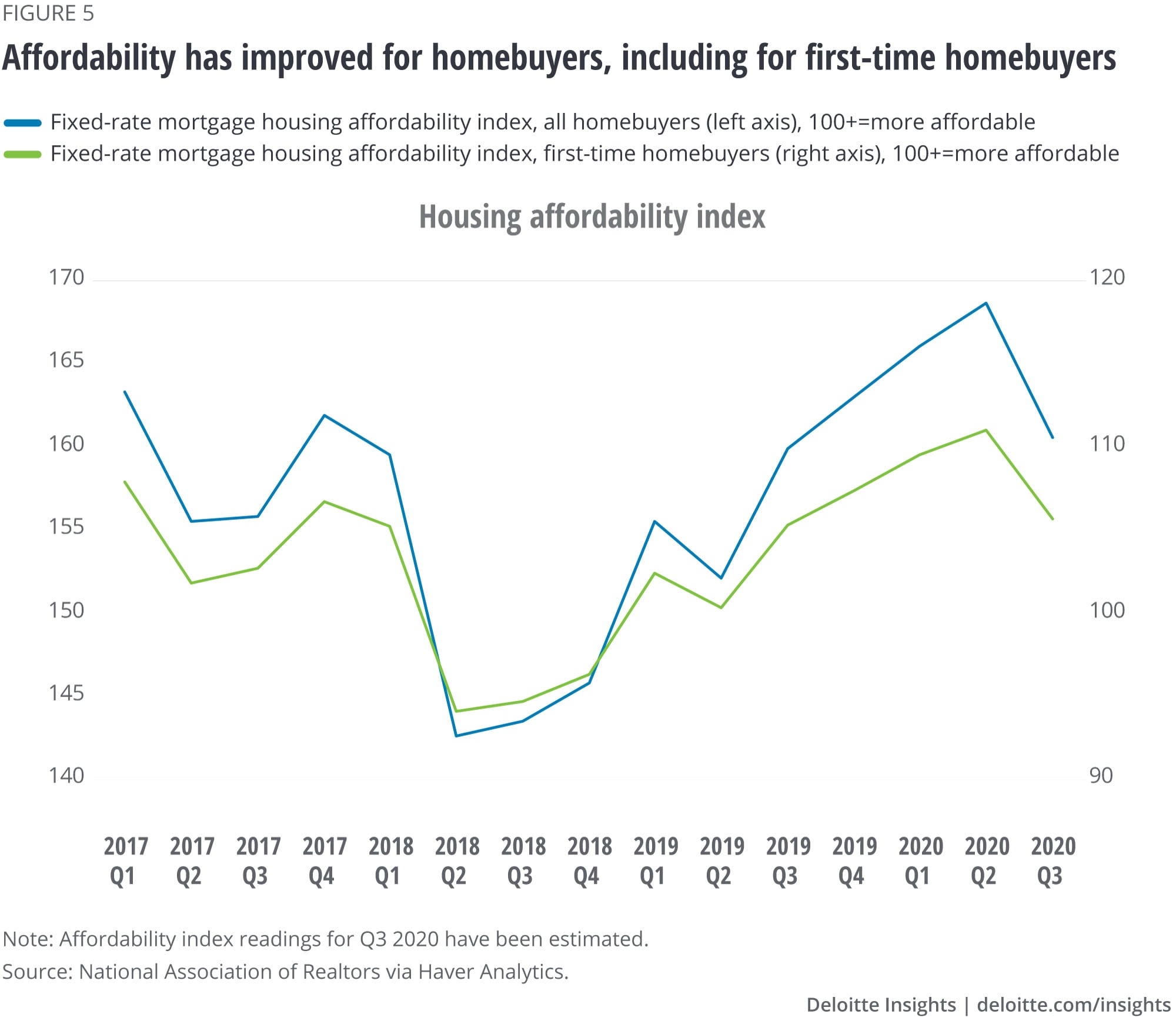

Falling mortgage rates and rising median household incomes have improved housing affordability, which has increased since mid-2018 for all homebuyers, including first-time homebuyers (figure 5). Though affordability took a hit in Q3 as home price appreciation likely overshadowed the fall in mortgage rates, it remains better than it was a year ago. First American’s Real House Price Index, which was down 9% from a year ago in January, was still down 6% in August.10

3. The millennial wave is coming of age

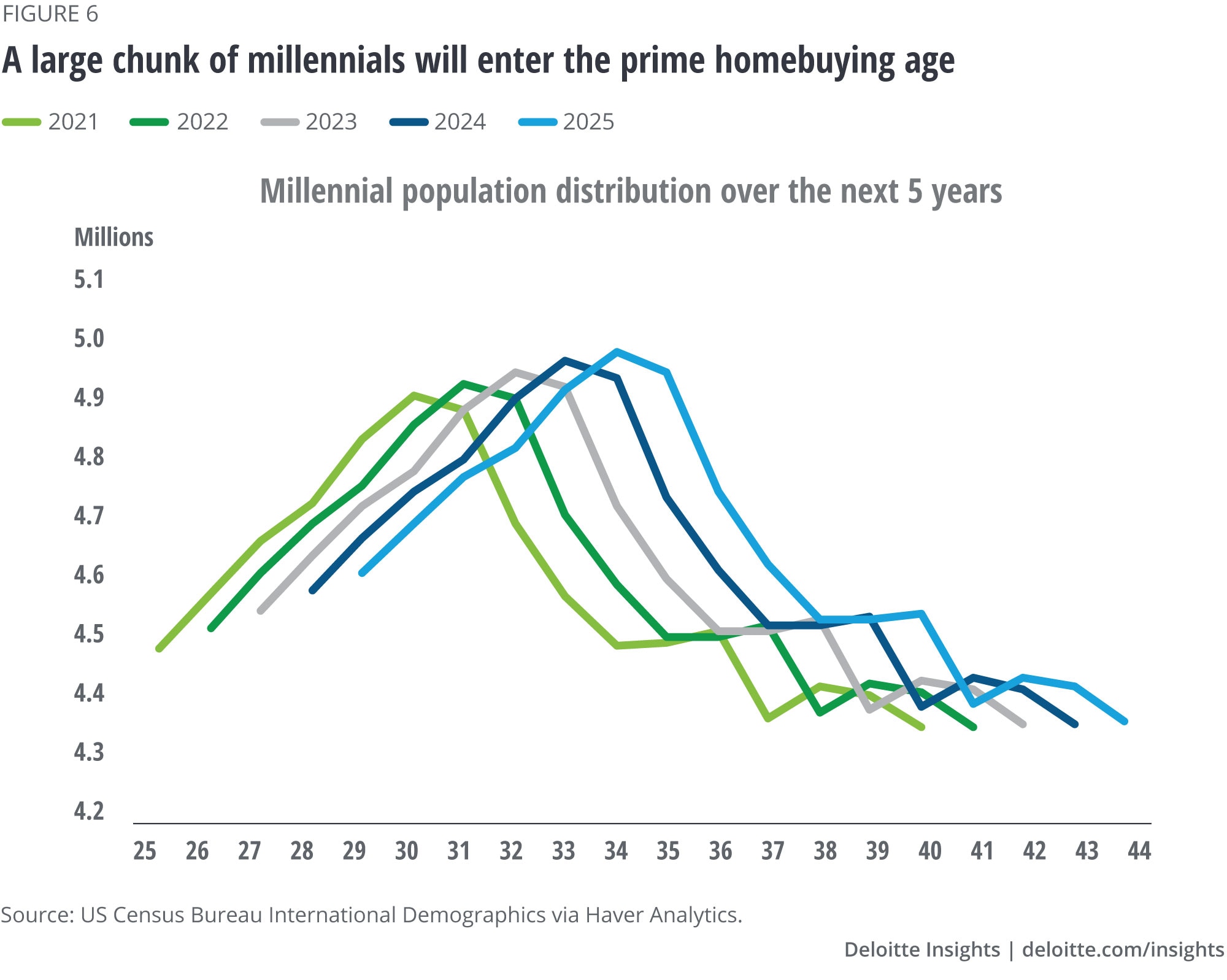

Americans are taking key life decisions, such as getting married and buying a house, later than in previous decades. The median age of first-time homebuyers has increased from about 29 years in 1981 to 33 years in 2019.11 This has implications for the millennial generation, which has often been tagged as a generation of renters—homeownership among the millennial generation is low at 43%.12 But this means there is room for increased homebuying, and the demographic distribution of the generation is likely to play a part. In 2021, a large wave of millennials will be on the cusp of entering the prime homebuying age for first-time buyers (figure 6), which is age 30–35. The number of millennials in this age group is projected to increase over the next five years. Millennials, while less likely to currently own homes, are increasingly likely to purchase homes. Millennials’ share of mortgage origination in 2020 is projected to exceed 50%.13

Is the housing boom likely to continue?

Elevated mortgage applications for purchase at the end of October indicate that housing market strength is likely to continue into Q4. However, there are some risks to the housing boom.

- The virus: If infections rise and lockdowns are imposed, housing construction activity could take a beating as it did in March and April. This could exacerbate the current inventory shortage.

- Thinning of the housing inventory: The lean housing inventory has raised the income required to qualify for a home loan at a time when the labor market remains weak. Even though the qualifying income is below median household income, and current demand for housing is being driven by higher-wage earners, a further thinning of the inventory, particularly of entry-level homes, might lock potential buyers out of the market.

- Housing demand is not endless: The pool of prospective buyers will continue to narrow as the boom continues. Furthermore, low interest rates, access to capital, and current needs might have brought forward a significant portion of future demand. In the medium to long term, a weak and protracted economic recovery will likely add fewer potential homebuyers to the housing market.

A tale of diverging realities

The housing boom is emblematic of the inequality that the pandemic has created. Income and wealth inequality narrowed between 2016 and 2019, but the gap might have widened in 2020. Not all existing homeowners are in a sweet spot. In July, we highlighted that millions of homeowners are struggling with mortgage payments due to a loss of income.14 Increased home equity might be a saving grace in the short term, but we could start to see a rise in foreclosures. The situation is direr for renters who, lacking the cushion of home equity, may face eviction. Therefore, even as we see home sales soar, homelessness could also increase.

More from the Economics collection

-

Eurozone economic outlook, September 2024 Article2 months ago

-

Brazil economic outlook, August 2024 Article2 months ago

-

G7 economies Article4 years ago