Digital platform as a growth lever Platform strategy can help companies transition from a “make one, sell one” model to become network orchestrators

16 minute read

29 July 2020

Deepak Sharma

Deepak Sharma Maximilian Schroeck United States

Maximilian Schroeck United States Anne Kwan United States

Anne Kwan United States Venki Seshaadri United States

Venki Seshaadri United States

Most enterprises struggle to leverage technology to simultaneously drive growth and operational efficiencies. This article, 11th in a series, discusses the adoption of a digital platform strategy to monetize new and existing offerings amid ongoing digital transformation.

Introduction: The age of platforms is here

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is well underway, with smart manufacturing, 3D printing, and other technologies driving fundamental market shifts and waves of digital-driven disruption. Many companies are seeing value being created and captured in novel ways, moving away from legacy products as standalone offers and toward the data and insights products and solutions generators. As this IoT-powered world matures, B2B enterprises must rethink their products and services to thrive in an Industry 4.0 environment—or risk being left behind by more nimble, digital-native competitors. In industries from advertising to manufacturing to enterprise software, value increasingly lies within data and information flows.

Learn more

Explore the Digital industrial transformation collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Over the past year, our Digital Industrial Transformation series has aimed to help organizations navigate this shift.1 In the series’s first article,2 we discussed how companies can capitalize on an Industry 4.0 environment by embedding new digital technologies and capabilities into their legacy assets. This article extends that idea, offering a perspective on how those same digital technologies and capabilities can be monetized via platform-based strategies.

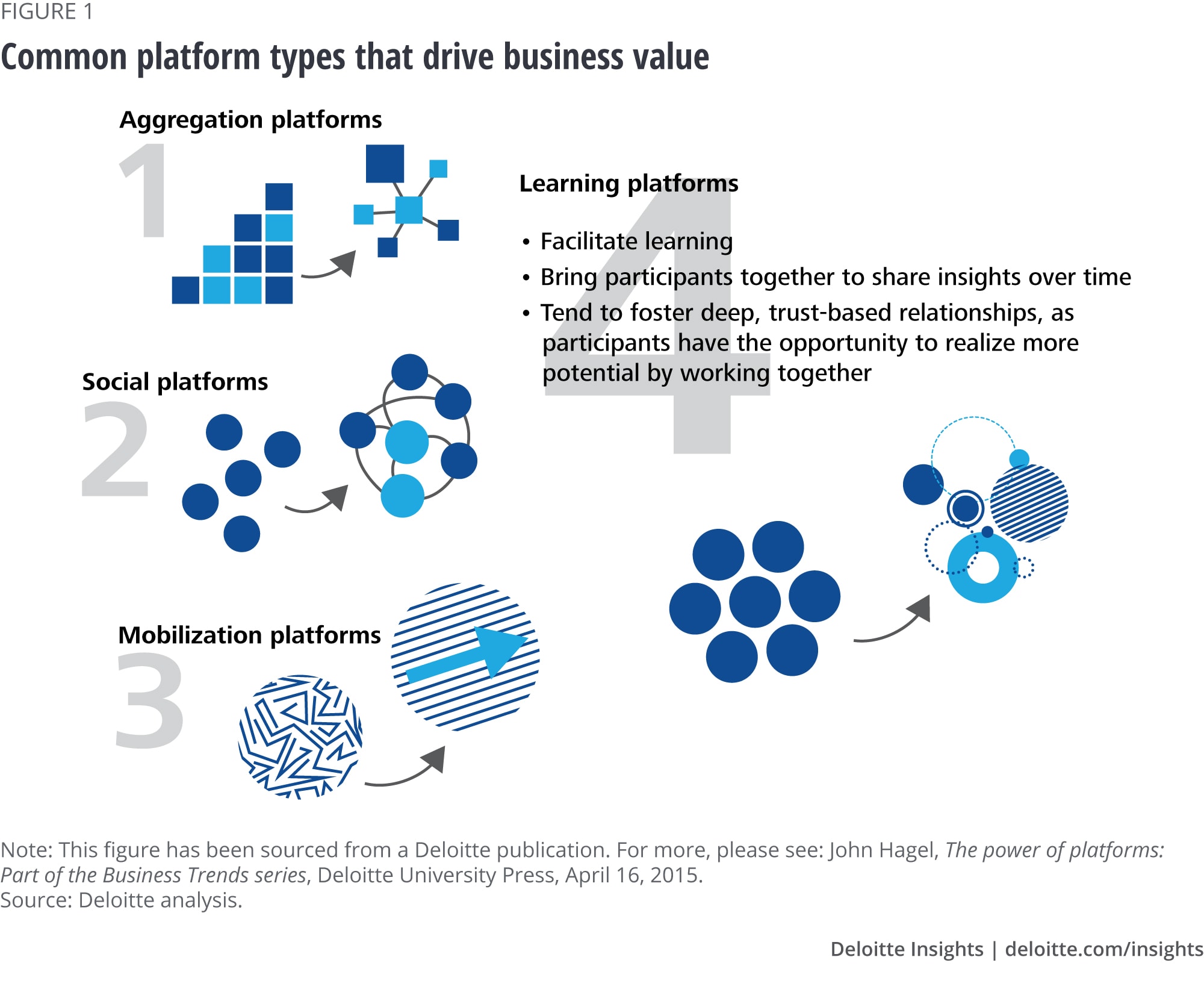

Once a novel idea, digital platforms have become increasingly common. At the most basic level, platforms help to make resources and participants more accessible to each other on an as-needed basis. Platforms are typically created and owned by a single entity—an orchestrator—that works to assemble a mix of foundational offerings compelling enough to encourage other players’ active participation. When designed correctly, platforms can become powerful catalysts for rich ecosystems of resources and participants. What occurs in these ecosystems varies depending on the nature of the platform and which players it convenes. Deloitte has categorized platforms into four categories (figure 1) that represent how an organization can create value for itself and participants.3

When designed correctly, platforms can become powerful catalysts for rich ecosystems of resources and participants.

Aggregation platforms bring together a broad array of relevant resources and help users of the platform connect with the most appropriate resources. These platforms tend to be transaction- or task-based and include marketplace and broker platforms.

Social platforms, which include some of the most widely known social networking sites, are similar to aggregation platforms in that they bring together many stakeholders. That said, social platforms are unique in the long-term nature of the relationships they facilitate—the goal is less about completing a transaction than about aligning individuals around areas of common interest.

Mobilization platforms take common interests to action. These platforms go beyond conversations and interests and focus on moving people to act together to accomplish larger goals. Because of the need for collaborative action over time, these platforms—including supply networks and distribution operations—tend to prioritize long-term relationships over isolated and short-term transactions. These platforms span a broad range of industries, including financial services, consumer products, and automotive.

Learning platforms are multisided networks that facilitate the transfer of knowledge, bringing together participants to share insights over time. These platforms tend to foster deep, trust-based relationships, with participants able to realize their potential only by working together.

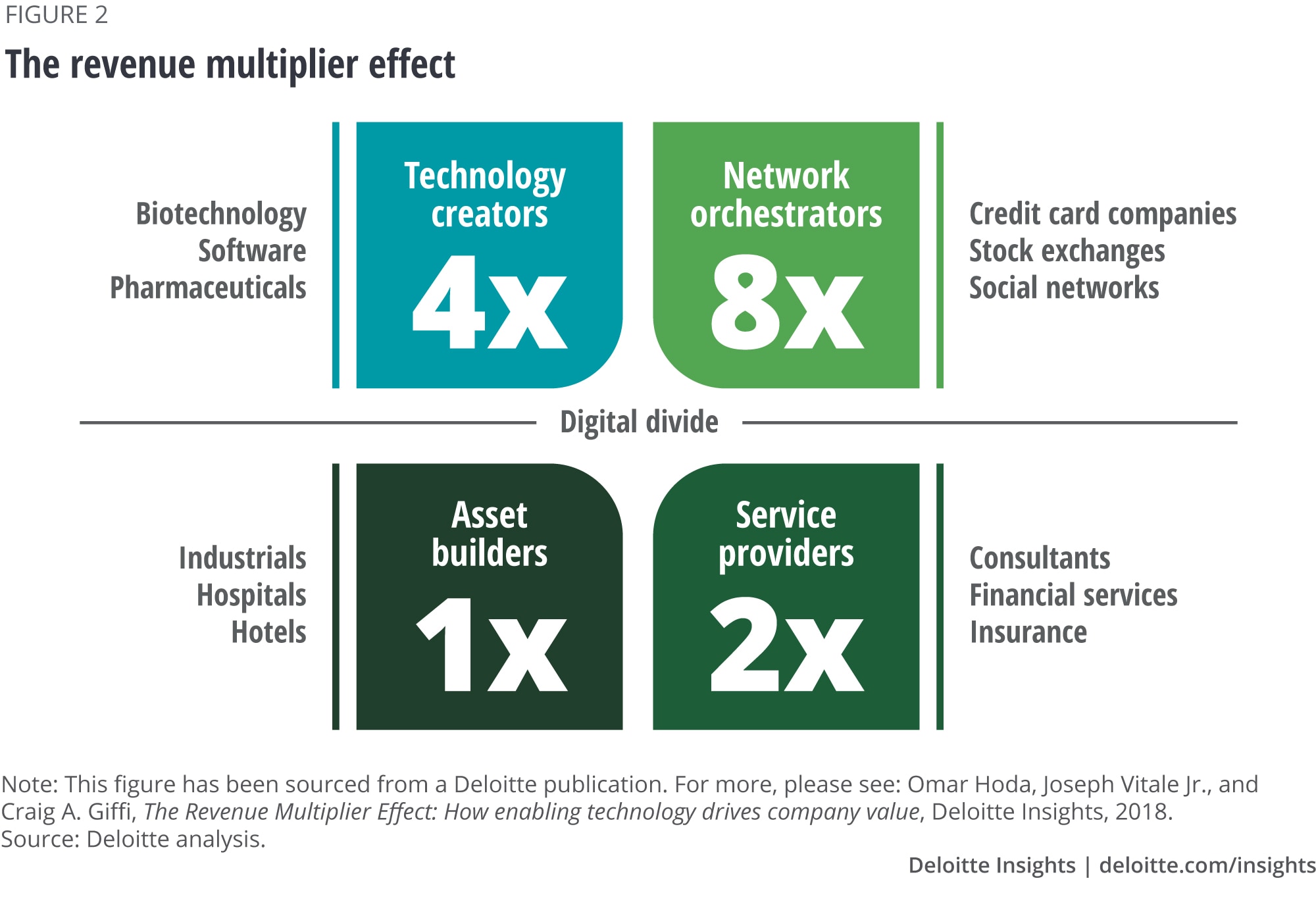

Together, these types of platforms are forecast to capture some US$10 trillion in global value over the next decade.4 Much of this value will be unlocked by companies that use platforms to fundamentally change the nature of how they operate and deliver value. Specifically, platforms can represent a transition from a traditional “make one, sell one” model to that of a network orchestrator, a “many make” model. This pivot insures against digital disruption and harnesses network effects to create, market, and sell goods, services, and/or information. Engineering this shift in your company’s identity and business model can pay dividends. In fact, Deloitte analysis bears out that the market values companies that are network orchestrators, with an average revenue-to-market-capitalization ratio of 8X versus 2X for service providers and 1X for asset builders.5 Figure 2 outlines how these valuation differences bear out across different industry archetypes.

Considering these benefits, it should come as no surprise that more and more executives are showing an interest in realizing the promise of platform-based strategies for their own businesses. That said, not every organization has a clear path to becoming a network orchestrator; many entities might be best suited to simply participate in one or more platform ecosystems. In evaluating whether to proceed with a platform-based strategy, leaders should begin by considering the following questions:

- Does our business align with a platform-based business model?

- Can we occupy major influence points on the platform to connect disparate parties?

- Can we develop a trust-based relationship with other partners on the platform?

- Do we have the capabilities to build and sustain a platform?

Further, orchestration of a platform requires specialized skills, executive support from the highest levels given the investments required, a strong competitive position (including key points of strategic control), and a compelling “right to win” to appeal to the end customer and other ecosystem players. If you believe your organization has what it takes to create a platform-based business, read on.

Preparing for platform transformation: A fundamental shift in business, culture, and mindset

For new platform entrants, a common error is to underestimate just how difficult it is to monetize your existing offerings, data, or capabilities in a new way. Building a platform demands an enterprise-level transformation; it requires new, digital ways of doing business and all that comes with them, including major adjustments in your people, your processes, and your technology systems. For many, the most challenging part of the journey lies in knowing where to begin and how to balance measured thinking with bold and decisive decisions.

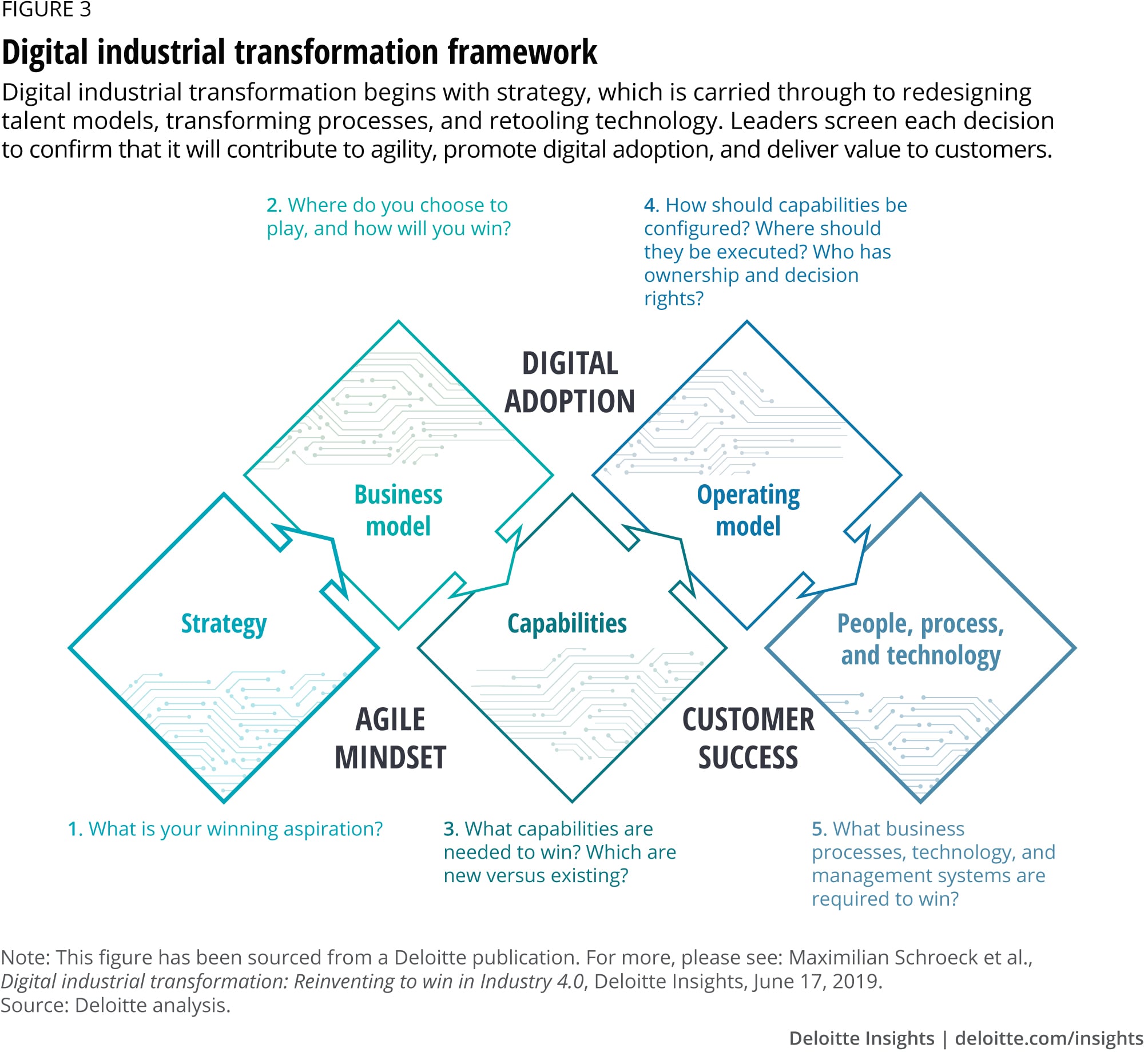

At Deloitte, we approach these issues through the context of the digital industrial transformation framework, which acts as a guide for organizations embarking on large-scale digital transformation. Launching a digital platform, for example, will require revisiting each of these five elements, starting with strategy formulation. From there, strategic choices carry through to business model redesign, development of necessary capabilities, creation of an operating model, and finally, acquisition of necessary people, process, and technologies. Figure 3 illustrates the interplay between these decisions and how, together, they create the basis for digital transformation.

The rest of this article will offer a deeper dive into steps one and two—developing your strategy and business model—and provide useful tools that you and your team can leverage as you begin your platform journey.

Define the platform vision: What value and for whom?

The first step in developing a platform strategy is to develop a compelling vision. Just as an organization might articulate a vision for a new business unit or product line, platform entrants should develop a compelling vision that articulates the goals and aspirations for its platform-based business. In this series’s second article, Setting the north star, we discuss critical success factors for a vision,6 including how a vision should be a clear, simply articulated message that ensures all stakeholders can understand the aspiration and intended outcomes. It should be mobilizing, clarifying employees’ purpose and keeping them engaged. It should foster alignment, allowing each function to begin to drive toward digital transformation goals. And it should excite customers and partners, signaling that the organization is positioning for the future in a way that can complement their Industry 4.0 aspirations.

It can be helpful to distill your vision into a single vision statement, which outlines this long-term end state for the platform and communicates its purpose to employees and other internal stakeholders. Put simply, your vision should answer three questions:

- What value is exchanged? Outlines what the “currency” of your platform is, which could include some combination of information, data, or goods and services.

- Who is involved? Outlines the participants in your platform, which will include some combination of producers (internal/external), consumers, and other stakeholders.

- How does it work? Outlines the respective tools and functionalities that bring stakeholders in, facilitate sharing, and match participants, etc., in your platform.

A vision statement could follow, for instance, the construct “[Platform Name] is a [category] platform that helps [core participants] to facilitate [essential exchanges] through [key functions].”

Of course, while the vision statement is a useful tool for galvanizing internal support and alignment, it is only a starting point. The vision statement is meant to be directional and can be refined over time. This statement can help us make choices about how to bring this vision to life. Indeed, you and your team have an infinite set of permutations and combinations of strategies at your disposal. Will you cater to small and medium-sized businesses or large enterprises? Where in the customer’s buying process should you invest most heavily? Will you aim to monetize via a subscription model or something more consumption-based? The sum total of these decisions is the composition of a strategy, which is nothing more than a set of choices on where (and where not) to focus.

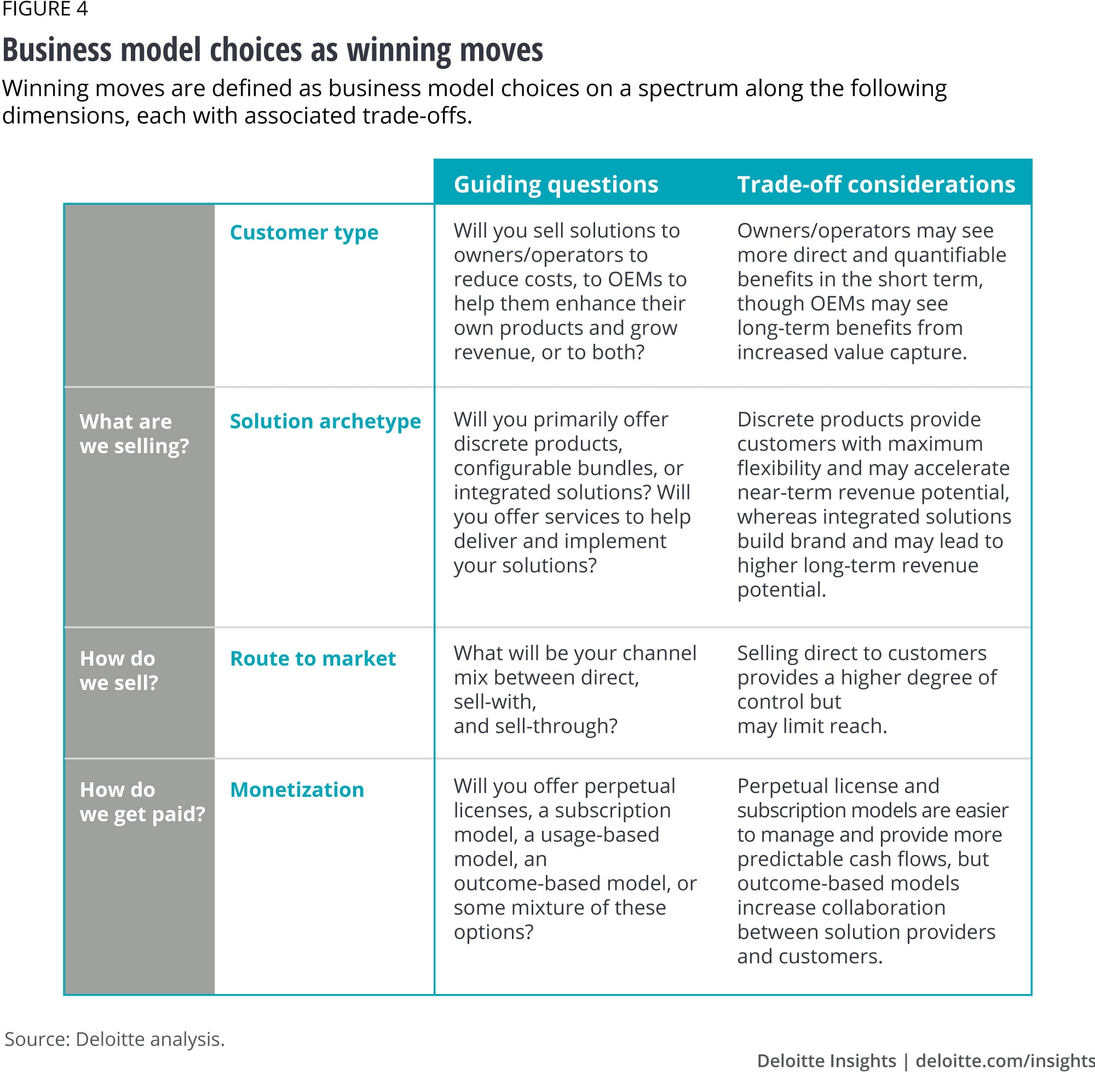

Deloitte’s business model framework, introduced earlier in this series, can help guide an organization in navigating these distinct yet interrelated choices. Figure 4 outlines three questions that collectively represent all the major elements of a successful platform strategy.7

- What will you sell? What portions of the digital solution stack will you offer? Will you target original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) or owners/operators?

- How will you sell? On which ecosystem partners will you rely to sell through and sell with? Are there new ecosystems you need to forge, and new partners to recruit?

- How will you get paid? Will you charge a subscription, or charge based on consumption or outcome?

Customer type: To whom will you sell your solution? What needs will you address?

The first and most important decision is determining which customers your platform will serve. This includes developing a robust understanding of both the users who will use your platform as part of the natural flow of their work/life and the leaders who may make the enterprisewide decision to migrate a current process to your platform. But how to identify a set of users to target? This depends largely on what pain points your platform is aiming to address. Although you could endeavor to build a platform that aims to mitigate every unmet need, it is imperative to identify the two or three pain points that are both compelling enough to support a digital business and something your organization has a “right to solve.” If the unmet needs addressed do not markedly improve customers’ status quo, or you don’t have a viable path to address them, then the platform will be unsuccessful. If done correctly, the upside is limitless. This process requires a deep understanding of unmet needs along the customer journey—from awareness to purchase to after-sales support.

Granted, identifying where opportunities lie can be difficult, and sometimes the thorniest issues are hidden in plain sight. Consider the Amazon experience as an example. As the company rapidly scaled its e-commerce business, Amazon and its partners found themselves building the same technical infrastructure, over and over again.8 The process was duplicative, repetitive, and costly. What if Amazon could build an internal business unit dedicated to the development of out-of-the-box infrastructure solutions, for use in its rapidly growing e-commerce verticals? It was from this seemingly mundane observation that the Amazon Web Services (AWS) platform was born. Simply by addressing its own issue, AWS was able to unlock a massive universe of customers facing the same challenges.

Solution archetype: What are the platform offerings and supporting capabilities?

The second decision involves platform offerings—the actual products or services that your platform will make available to target customers. Of course, the decisions made here should be anchored in your understanding of the platform’s target customers.

Consider Salesforce, whose marketplace platform brings together businesses of all kinds, independent developers, and implementation consultants in addition to the company’s own relationship managers and product developers. In its early days, when the platform was in startup mode, Salesforce targeted small and medium-size businesses that could benefit from the simplification of IT functions that Salesforce was seeking to create. It was this focus that—at least in part—led to the creation of the Salesforce AppExchange, a crowdsourcing marketplace for customer relationship management (CRM) solutions known for its ease of use and accessibility, for even small customers.9 More recently, Salesforce has launched what it calls “Salesforce Essentials,” optimized for small businesses.10

Route to market: How do we sell?

Having identified target customer type and offering set, the next decision focuses on the route to market, or how to sell. Implicit in the decisions made here are choices about whether to build capabilities, buy capabilities, or partner with a third party in order to deliver the desired experience. After taking stock of a company’s internal capabilities, it may become clear that partnerships are necessary to execute the desired customer experience. Partnerships can often be an ideal course of action if the need for differentiation or strategic control over that capability is low. If rapid speed to market is required or if market uncertainty is high, partnerships can be a lower-risk way of testing a new market. For example, AWS partners with consulting firms to sell and implement AWS solutions, as this offers AWS greater market penetration while helping partners differentiate their business offerings to clients.11 For more information on the decision to build, buy, or partner, see our article on strategic alliances, Ecosystem-driven portfolio strategy.12

Also implicit in this step is the identification of your platform delivery mechanism. This involves a deep understanding of how customers and partners would prefer to interact with your product and service offerings and is key to enabling an efficient customer experience. Do customers value the asset-light, cost-effective approach that a cloud-based solution might provide? Or would they prefer a licensed, on-premise solution that might better accommodate customers who prioritize data security and privacy? Salesforce’s customers, for example, place a premium on scalability, which makes the company’s out-of-the-box, cloud-based solution a natural fit.13 Similarly, Amazon provides modular, cloud-based physical storage and distribution capabilities to vendors while offering users a seamless online experience.14

Partnerships can often be an ideal course of action if the need for differentiation or strategic control over that capability is low.

Monetization model: How do we get paid?

Finally, monetization is an important consideration to ensure the sustainability of the platform. Organizations should first determine the offer structure (free or fee-based). If fee-based, there are other options to consider, including fixed-/pre-paid, subscription (unlimited), subscription (predefined), freemium, consumption-based, and outcome-based. Selecting the monetization model depends on how customers intend to interact with the platform. For example, Amazon’s pay-as-you-go model allows customers to adapt to changing business needs without overcommitting budgets or missing capacity.15 Similarly, Salesforce works on a subscription (predefined) model and charges a fee based on tiers of usage and functionalities for users.16 Monetization strategy will be important as you start to communicate the platform vision with internal stakeholders and begin to validate the idea with customers and partners.

These decisions, taken together, form the initial basis for your organization’s entry into a platform business. Note that these decisions can—and probably should—change as the platform evolves. Business blueprints can serve as powerful tools if they include flexibility for your business model to change and evolve as you receive feedback from customers. For example, Amazon’s initial business model began as an online bookstore but left enough flexibility to reinvent the company several times over—first to a general e-commerce platform and then to a data warehousing solution.17

Identify assumptions and uncertainties ahead: Why might we be wrong?

Building this business blueprint is like a grand experiment for your company. As with a scientific experiment, your blueprint should be anchored in hypotheses about your platform business model, informed by high-level market analysis and an understanding of your company’s capabilities. Inherent in this preliminary understanding of your platform are assumptions and beliefs about how your platform might drive value and about the ecosystem of partners and users it will convene. Our success depends on pressure-testing these hypotheses and, in so doing, understanding exactly what we know and what we don’t know about the potential of this idea. Essentially, we want to identify our blind spots by asking, “Why might we be wrong?”

So how do we test these blind spots? At Deloitte, we use a balanced breakthrough model, a framework that tests feasibility, viability, and desirability to identify where weak points might exist in a vision and corresponding blueprint.

Desirability: Do customers and/or partners need the platform? This question aims to understand the motivations and core beliefs of our customers and partners. Every successful platform innovation has been fundamentally human-centered. As such, we must ask ourselves pointed questions about whether the platform vision and blueprint choices resonate with the people whose unmet needs we seek to address. Questions to ask about your vision and blueprint include:

- Will customers change their behavior to use the platform?

- Do platform capabilities (as imagined) address users’ unmet needs in a compelling way?

- Is there sufficient incentive for partners to join the ecosystem created by our platform?

Feasibility: Can the platform be developed? A new platform can be extremely valuable and can certainly provide the basis for an improved customer experience, but a desirable idea is not enough. Your platform vision and blueprint must be feasible and implementable. Questions to ask here include:

- Do we have the capabilities to develop the platform as we have imagined it?

- Do we have the appropriate in-house talent to make this happen?

- Can we accelerate platform commercialization by connecting it with more mature ecosystems?

Viability: Is there value for our enterprise? Is the opportunity significant enough? This factor speaks to financial opportunity. Questions to ask about your vision and blueprint include:

- Can we effectively monetize the offerings in our platform?

- Will users be willing to pay?

- Can we create a competitive position with this platform given the current (and future) market landscape?

Thinking through these questions of desirability, feasibility, and viability can help refine your platform concept, strengthen your business blueprint, and identify (and mitigate) blind spots that could jeopardize your platform in the future. That said, simply cataloging these issues can only be so helpful. At a certain point, you and your team will need to get out into the field and rigorously test these hypotheses. In the next section, we’ll discuss how you can use a minimum viable platform (MVP), and other techniques, to pressure-test your platform concept.

The path to commercialization: Developing an MVP

Just as scientists might use controlled experiments to test assumptions about the world around them in an iterative, data-driven way, you and your team will need controlled experiments to test assumptions about the platform. In our case, these “experiments” are known as iterations of MVP, a version of a new platform that includes only the most essential elements—such as a barely working prototype—to test how target customers will react to your platform. An MVP should meet the following requirements:

- Build our initial set of capabilities within a predetermined time frame to validate our thinking with customers/partners

- Allow for flexibility to scale offerings from the MVP

- Test our most critical uncertainties—for example, does the platform offer capabilities that address customers’ unmet needs in a compelling way?

For the most ambitious leaders, it can be difficult to purposely constrain the scope of your efforts. In a world where tech giants are transforming industries and reaching billions of users through expansive network effects and multiside marketplaces, it may be difficult to take a step back from your grand vision and settle for a more limited, preliminary iteration. It should be noted, though, that many of the most significant platform-based companies—those now shaping our world—started with humble prototypes in the beginning. Amazon, for example, which now touches nearly every industry with a variety of software, hardware, and commerce offerings, started by selling books, with an MVP that Jeff Bezos thought could effectively test his vision.18

The common thread among all these MVP efforts: Leaders invested in developing just enough of the platform so that a small set of customers could react to something. Even these massive platform-based companies began with what were essentially wire-frame models that they presented to customers and asked, “What do you think?” Indeed, customer feedback (and mechanisms to collect it) will be key to understanding how your platform vision and blueprint choices resonate with customers. This feedback will help you to tweak functionality, adjust the value created, and even make go versus no-go decisions down the road.

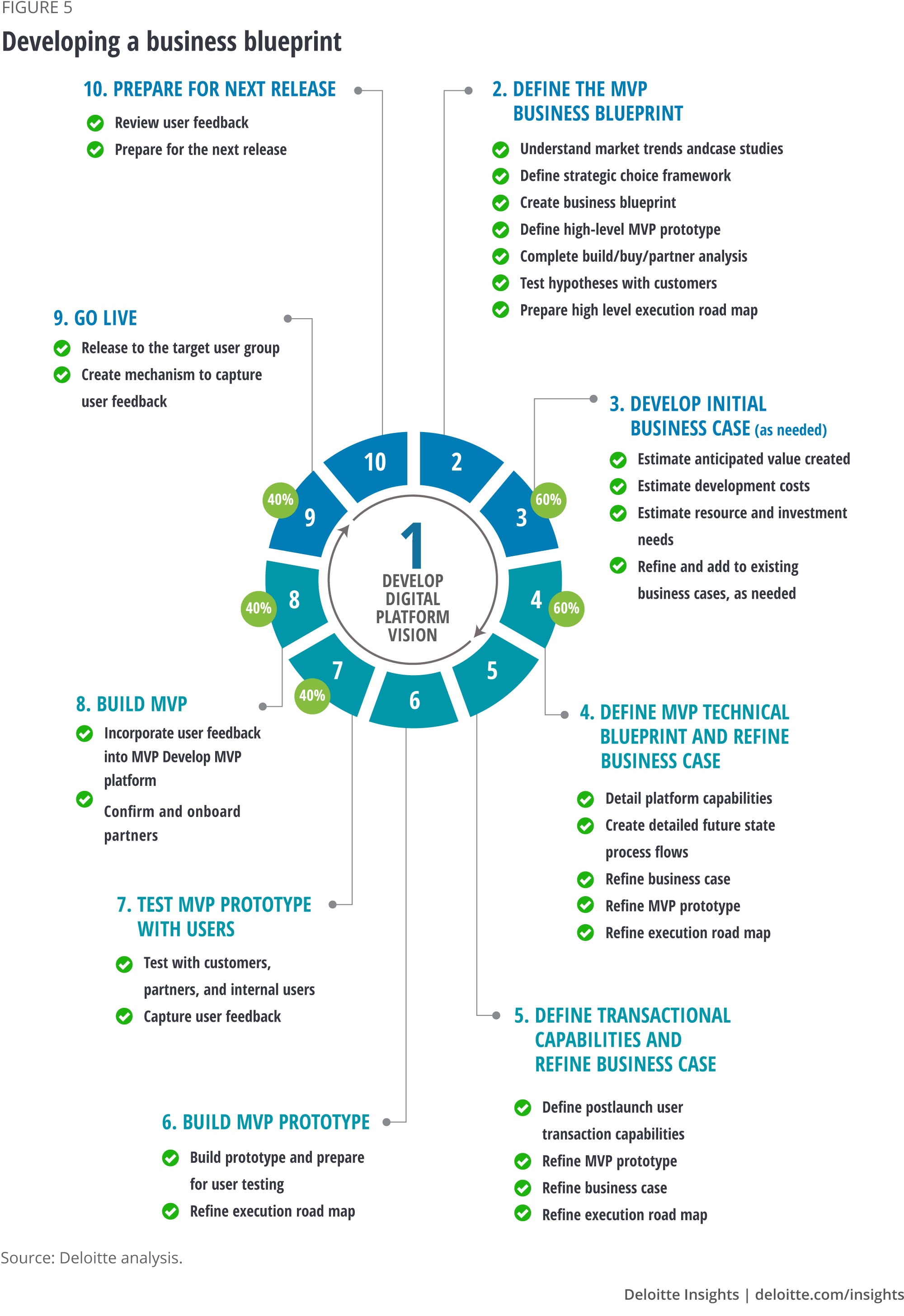

The initial MVP is only the first step in a larger effort. As you receive confirmation from the market that your platform business blueprint is on the right track, you can introduce subsequent MVPs that will be tested through iterative, agile sprints. Navigating this process, as figure 5 illustrates, will feature a concurrent push and pull of developing functionality on the one hand and testing with customers on the other.

The common thread among these MVP efforts: Leaders invested in developing just enough of the platform so that a small set of customers could react to something.

These activities will not occur without concerted investment and resources, and you and your team will need to take a series of actions to ensure this process has what it needs to succeed. First, you’ll need a strong execution team. Tap dynamic individuals who can both manage the present and envision the future simultaneously. Second, you’ll need a robust governance model complete with well-defined roles, a transparent decision-making process, and progress tracking at the initiative- and program-level. Third, it is important to avoid measuring this dedicated team under status quo performance measures. It is entirely possible that this team could succeed, making significant progress in the development of the platform, and yet still “fail” under traditional performance metrics, such as profitability. For more information on developing an operating model, see our article Architecting an operating model: A platform for accelerating digital transformation.19

Conclusion

While these initial steps in developing your platform business are important milestones, they collectively represent the beginning of a longer transformation journey. A journey that begins with the initial MVP is winding and will require patience and vision.

Salesforce’s journey is a case in point. It took the CRM giant roughly 10 years—an entire decade—before it grossed US$1 billion in annual revenues.20 Those 10 years also hold the key to the company’s success. When the dotcom bubble burst in 2001, wiping out many of its clients, Salesforce stayed the course and doubled down on leaders’ vision of being “a world-class internet company for sales force automation” and continued with an aggressive marketing strategy themed around “end of software.”21 Over the next several years, as new as-a-service companies arrived in the market, Salesforce continued to expand its ecosystem and capabilities through offerings such as AppExchange and IdeaExchange, offering third-party developers a platform to build and sell custom applications on top of Salesforce, and inviting customers to contribute new feature ideas for future releases.22 “We believe,” says chief innovation officer Simon Mulcahy, “that our digital platform offerings are powerful enablers of customer-centric transformations and a value multiplier for everyone in the Salesforce ecosystem.”

All of this is to say that the road ahead, while rewarding, will not be necessarily easy. Companies planning to embark on a platform journey need to critically think of their value proposition and steadfastly work to build a robust partner and user ecosystem, while continuing to drive value for its ecosystem participants.

Explore the Digital transformation collection

-

Scaling up anything as-a-service Article5 years ago

-

Customer-centric digital transformation Article5 years ago

-

Architecting an operating model Article5 years ago

-

Digital transformation as a path to growth Article5 years ago

-

Staying focused and on track in Industry 4.0 Article5 years ago

-

Digital industrial transformation Article5 years ago