Loss of health insurance from the pandemic Helping Medicaid and health insurance exchanges know their future customers

15 minute read

20 August 2020

Many Americans who lost their jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic are shopping for health insurance coverage among health plans in Medicaid and exchange markets. Knowing these consumers’ behaviors can help plans serve their consumers better.

Executive summary

Millions of Americans have lost their jobs—and employer-sponsored health insurance—since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. While some people might be able to stay on employer benefits for a while or shift to their spouse’s or parent’s coverage, many others will have to seek coverage elsewhere.1 Early analysis indicated that most individuals who lost employer coverage would be eligible for subsidized coverage, either through Medicaid or the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health insurance exchanges.2

Learn more

Explore the health care collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Health plans that are already in Medicaid or exchange markets will likely see an increase in enrollees; other health plans may enter or expand into these lines of business. In designing their marketing strategies, health plans should understand what support and information their enrollees are looking for when shopping for plans and how to structure benefits and provider networks. Health plans should also want to support consumers who are facing challenges on multiple fronts—job loss, health, and other impacts from the pandemic.

Deloitte’s 2020 Survey of US Health Care Consumers can help shed light on the exchange and Medicaid populations from right before the start of the pandemic along with Deloitte’s Health Care Consumer Response to COVID-19 Survey, fielded during the pandemic. Both surveys show that people in Medicaid and exchange plans are increasingly interested in and using digital and virtual health tools. These are some of the behaviors and attitudes that are consistent with our vision of the future of health—a vision that includes consumers being more empowered to focus on well-being and managing their health conditions.

For people in health insurance exchanges:

- Consistent with what we found in earlier research, of all of our coverage groups (comparison is between people with employer coverage, Medicare, and exchange), exchange consumers are the ones most likely to be shoppers and use tools to look up costs. About a third of exchange consumers looked up information on prices of drugs and health care services compared to 29% (drugs) and 27% (health care services) of those with employer coverage.

- Even prior to COVID-19, they were already the largest users of virtual care and showed strong interest in using new technologies to manage their health.

- They use digital tools to track their health and are most willing to share their information. For example, 45% of exchange enrollees are using wearables for fitness, second only to the employer group, at 52%.

For people with Medicaid coverage:

- Consistent with earlier research—and counter to common assumptions about people with Medicaid—many in this group are eager and able to use technology to engage with the health care system and health plans and to manage their health.

- Medicaid enrollees (30%) are just as likely as those with employer coverage (31%) to say they use technology to monitor health issues (e.g., blood sugar, blood pressure, mood).

- People in Medicaid are already among the most likely to have had a virtual visit or consultation. Around a quarter had one of these visits in the last 12 months and another 10% had one in prior years. In 2020 (including during the pandemic) our COVID-19 survey showed the highest use of virtual health among Medicaid consumers compared with other insured groups.

In our 2020 Survey of US Health Care Consumers, 84% of people with Medicaid meet our definition of low income (having incomes at or below 250% of the federal poverty level), and 41% of people in exchange plans are low-income.3 Although people with all types of health coverage and at all incomes can face challenges with the drivers of health—factors outside the traditional health care system that impact our health, such as food security—these challenges are often especially acute for people with lower incomes. Lower-income people also face increased challenges getting access to mental and behavioral health services. The pandemic, with its disproportionate impact on low-income, disadvantaged populations, has shone a harsh light on the issues of disparities and inequity in health care.4

Among the survey respondents:

- Medicaid consumers and those who are uninsured are most likely to say they face challenges having enough money for food (47% for Medicaid) and being able to pay for housing (51% for Medicaid).

- Although fewer people with exchange coverage are likely to say they face challenges with these issues compared with the Medicaid population, at least a quarter of them said they do. With widespread unemployment, these issues are likely to have grown since March.

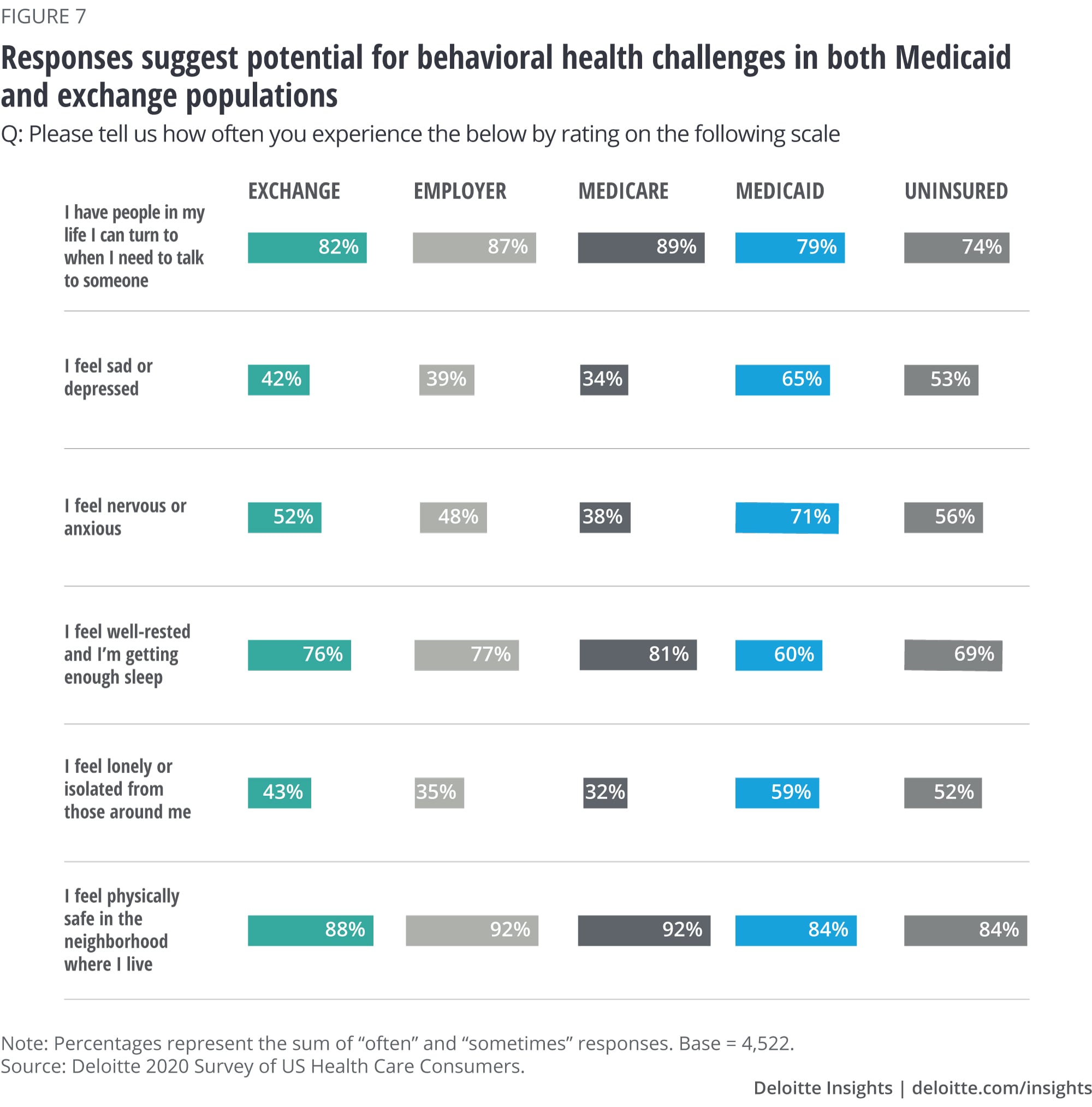

- Moreover, these populations face mental health challenges. In our survey, we found 71% of Medicaid consumers feel nervous or anxious and 65%, sad or depressed. Although the percentages are lower for the exchange population at 52% and 42%, respectively, they are higher than for most other groups. Our Health Care Consumer Response to COVID-19 Survey, fielded during the pandemic, found that people with Medicaid were most likely to report that they had felt anxiety or fear “a lot.” Medicaid and exchange consumers also were more likely to report they had felt uncertainty or lack of control “a lot.”

To attract enrollees, health plans offering or launching products in either Medicaid or exchange lines of business should take these findings into account, prioritizing investments in digital tools, benefits, and networks. Health plans may also want to consider how to approach people with empathy and sensitivity, and help them feel supported and understood during this time of uncertainty. Only about half of respondents to our Health Care Consumer Response to COVID-19 Survey felt supported by their health plans. Building trust with consumers is critical.

The COVID-19 pandemic is causing shifts in insurance markets

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to record job losses. From April to May 2020, more than 36 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits—levels not seen since the Great Depression.5 In addition to loss of income, many of these workers also lost access to their employer-provided health insurance coverage.

A key question for many health plans has been: Where will these individuals land? Some people who lose their jobs might be able to switch to an employed spouse’s coverage, get on a parent’s plan, or stay covered by their previous employer through a COBRA package. Policymakers have taken some steps to shore up employer-based coverage, and loss of coverage in this line of business is lower than might have been expected without these policies. But many people are likely to turn to coverage through health insurance exchanges, other individual market coverage, and Medicaid. The remainder will likely become uninsured, especially likely if they live in a state that did not expand Medicaid. Early analysis indicated that more than 26 million individuals would lose their employer-based insurance.6 The same analysis found that most (79%) of those individuals would likely be eligible for subsidized coverage either through Medicaid or the ACA’s insurance exchanges.

Many health plans may be looking at the expected enrollment increases in the exchanges and Medicaid enrollment and considering whether to expand their presence in or re-enter those markets. Obviously that decision will rest on important financial considerations. An analysis of health plan financial performance in the exchanges has found more stability in premiums and profits in recent years.7 Medicaid performance varies significantly by state, since states set premium rates, benefit packages, and other program elements.

Another consideration is risk selection—people coming from employer coverage may be relatively healthy, but competitive dynamics can be unpredictable. People are switching coverage at a time when health care spending is possibly even harder to predict than after the passage of the ACA. There is uncertainty about the cost of treating COVID-19, long-term effects of the virus in some populations, when nonurgent services will come back to prepandemic levels, the impact of missed care, and other negative effects on health outcomes due to the economic downturn and other stress factors.

While we do not have answers to how enrollment will evolve, we do have information on the perspectives and attitudes of both the exchange and Medicaid populations, which insurers could use to shape their consumer enrollment strategies.

About the surveys

Deloitte’s 2020 Survey of US Health Care Consumers sampled 4,522 adults (aged 18+) using an online panel chosen to ensure they are nationally representative with respect to demographics and insurance status. We fielded the survey from February 24 through March 14, 2020, before most states started social distancing policies. We fielded the Health Care Consumer Response to COVID-19 Survey in April 2020—at the peak of the COVID-19 crisis. That survey queried 1,159 health care consumers to understand the emotional toll of the pandemic and how their attitudes and behaviors in managing their health and well-being are changing.

Exchange and Medicaid enrollees are interested in health care digital and technology tools

Both populations are interested in and are using technology for a range of health care purposes. These include shopping for health care services (a more salient issue for exchange consumers, who face more cost-sharing), virtual visits with their doctors, and tracking their own fitness. This interest shows some degree of activation and agency in these populations, both of which we consider in our vision for consumers in the future of health. Health plans can offer these tools and expect pickup.

Demographics’ impact on responses

For the exchange and Medicaid populations, some of the differences we see in the responses to the survey questions may reflect differences in the demographics of people in our survey; we have not controlled for demographic or socioeconomic differences in the responses. Exchange consumers who answered our survey tend to be younger than the overall population and have lower incomes but the same level of education. Medicaid consumers, on the other hand, have lower incomes and lower levels of education.

Exchange enrollees shop around for best prices and coverage; Medicaid enrollees look for information on their conditions

One of the goals for the exchanges was to create a system where health plans would compete on price and other offerings, and consumers would actively compare prices and products. Consistent with what we found in earlier research, exchange consumers are shoppers. Many are willing to use cost tools: Thirty-four percent looked up price information on drug prices and 33% on service prices (figure 1).

Because Medicaid requires only minimal cost-sharing, shopping for price information is less relevant for people with coverage from this source. However, Medicaid enrollees are as likely to look up information about their health condition (52% compared with 51% for employers) and somewhat more likely to look up information about their medication (38% compared with 33% for employers) than most of the other groups.

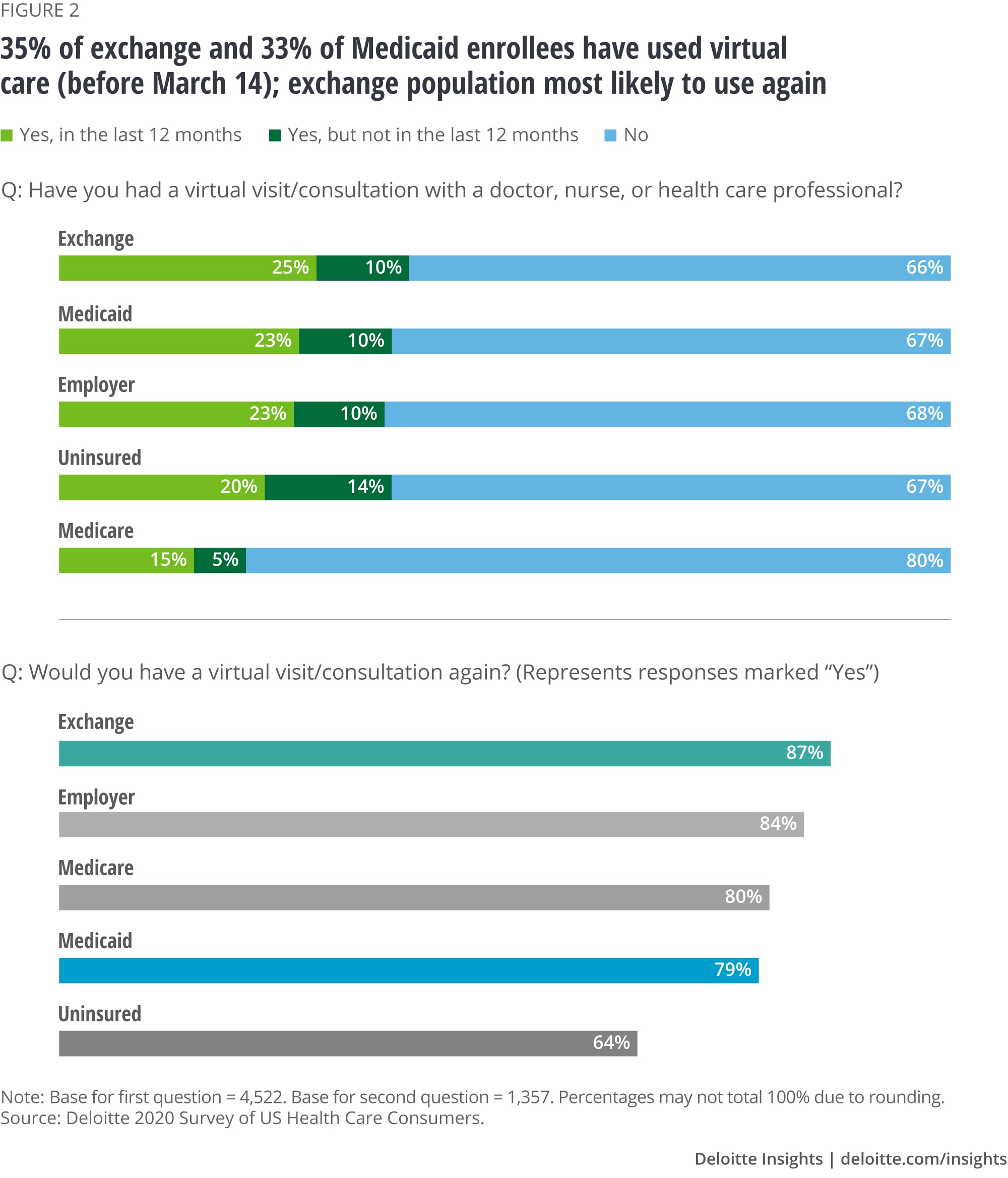

Exchange and Medicaid consumers like virtual care

Even prior to COVID-19, exchange and Medicaid consumers already were among the most likely to have had a virtual visit or consultation, and the COVID-19 survey showed this continued to be true for Medicaid. For the survey, we defined virtual health as allowing an individual to connect with a health care professional via a digital connection through a computer, tablet, or smartphone. Around a quarter had had one of these visits in the last 12 months and another 10% had had one further in the past. Exchange consumers had among the most positive response in terms of interest in a subsequent visit—87% would have one again. Medicaid consumers were slightly less interested in subsequent virtual visits (79%).

Note of course that in April and May of 2020, virtual visits have become common for enrollees in all lines of business. Our COVID-19 survey shows that most people say they will try virtual visits again, especially Medicaid and exchange consumers (figure 3). This data provides some evidence that interest in virtual health will persist even as face-to-face visits become common again.

Consumers are using digital health tools more

In general, consumers are using digital tools more for a whole host of purposes in health. Our survey found that exchange consumers—perhaps reflecting the skew our survey had toward younger respondents—was the group with the highest reported use of trackers to measure their fitness and health improvement, with 45% reporting they use these tools. Use was lower among people with Medicaid, although still fairly robust at 38%.

Among consumers using fitness trackers, exchange consumers were among the most likely to report data from their fitness trackers to their doctors (56% vs. 43% of people with employer coverage, for example). More than half of them said they are willing to share this type of data with health plans.

Exchange consumers are also most likely to report that fitness-tracking devices are likely to have a positive impact on their health. Among the exchange consumers with trackers and devices, 44% said the technology had improved their behavior a great deal, and 41%, a moderate amount.

Another common tool consumers used was for reordering a repeat prescription supply; 36% of both exchange and Medicaid consumers reported they had used tools for this purpose (figure 3).

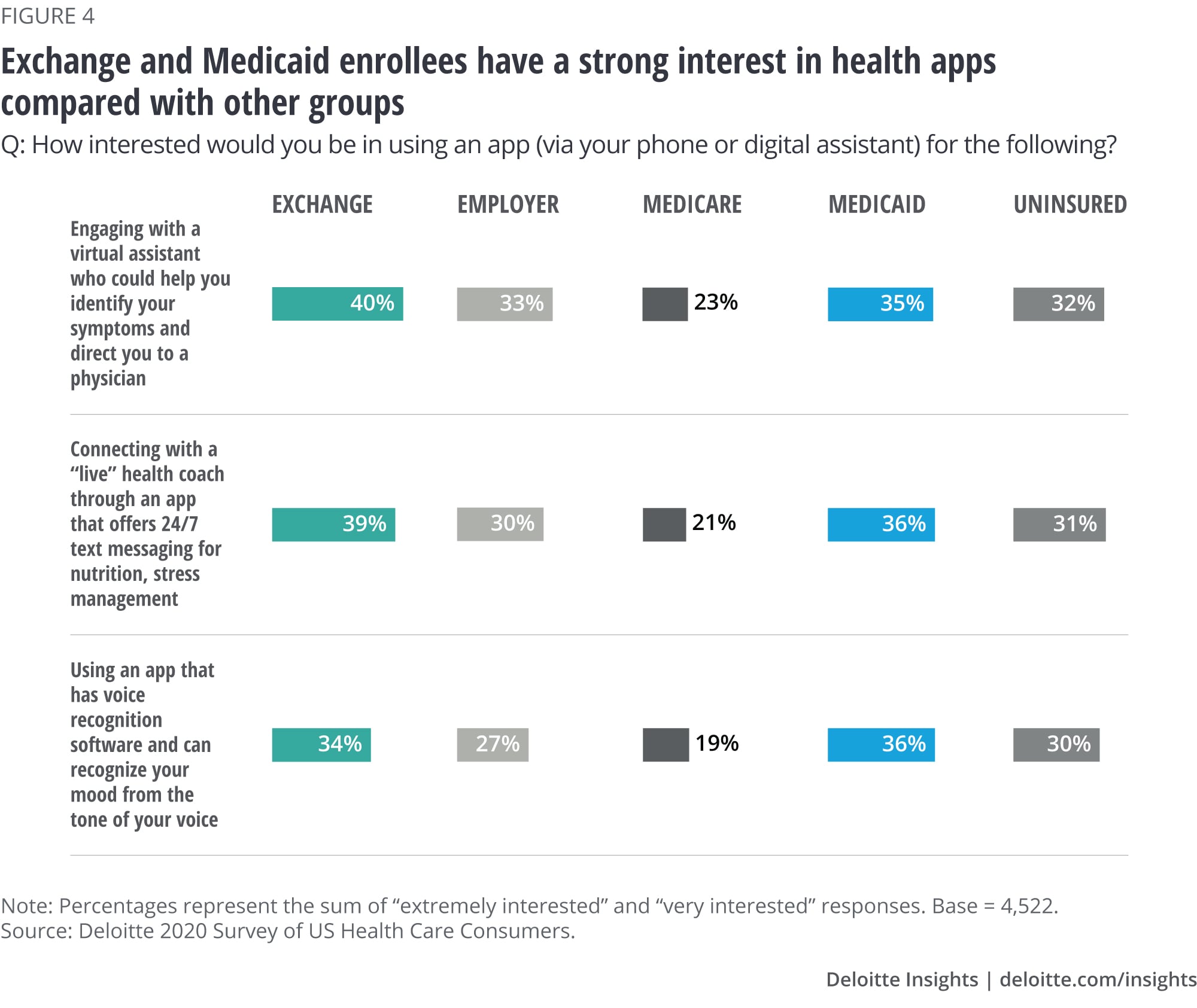

Finally, consistent with their interest in technology in general, both exchange and Medicaid consumers are interested in health apps for other purposes. For example, 40% of exchange consumers and 35% of Medicaid consumers are interested in engaging with a virtual assistant (figure 4).

Consumers are showing signs of loyalty to health plans

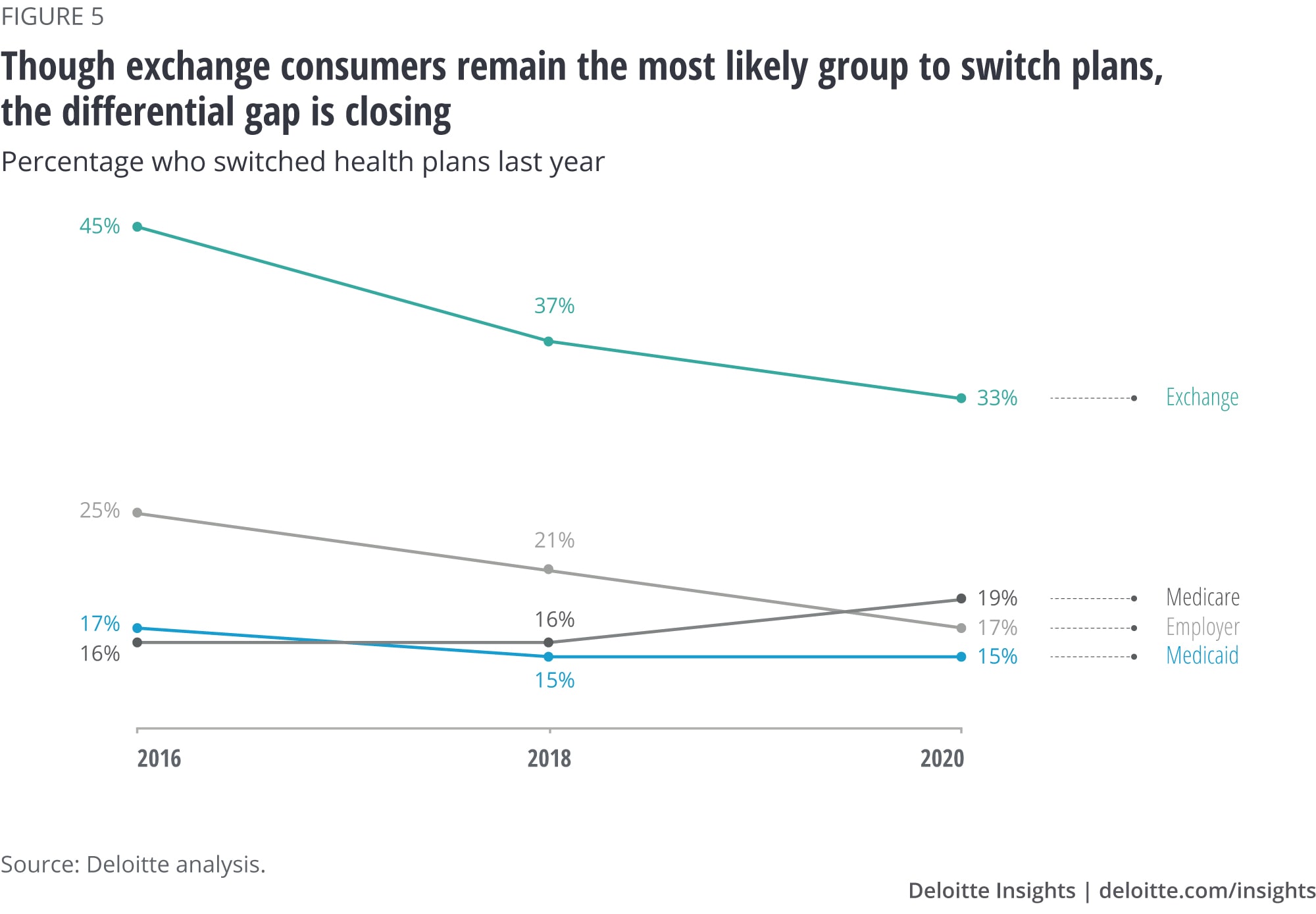

Health plans in the Medicaid and exchange markets have experienced high levels of enrollment “churn”—they lose and gain members as the latter get or lose access to employer coverage or their income or residence changes. Economic recovery from the pandemic may lead to more churn—as the economy and hiring recover, people who turned to Medicaid or exchange coverage might go to employer-offered coverage. Some employers under financial pressure might decide not to offer health insurance. If the recovery takes longer, churn might go up if states—facing significant budgetary pressure—take action to reduce the number of enrollees.

We did not directly measure churn in the survey, but we did ask respondents to tell us whether they had switched plans within the last year. Switching of plans among exchange consumers has declined over time, and it has been stable for people in Medicaid-managed care plans between 2016 and 2020. Switching fell from 45% of exchange consumers in 2016 to 33% in 2020; the length of time they had the same plan or policy was longer in 2020 than in 2016. This might reflect the stability in participation, benefits, and premiums in exchange products in recent years. Consistently over time, 15% of Medicaid enrollees we surveyed have said they switched plans in the last year (figure 5)

Health plans can help consumers address drivers of health through tools and services

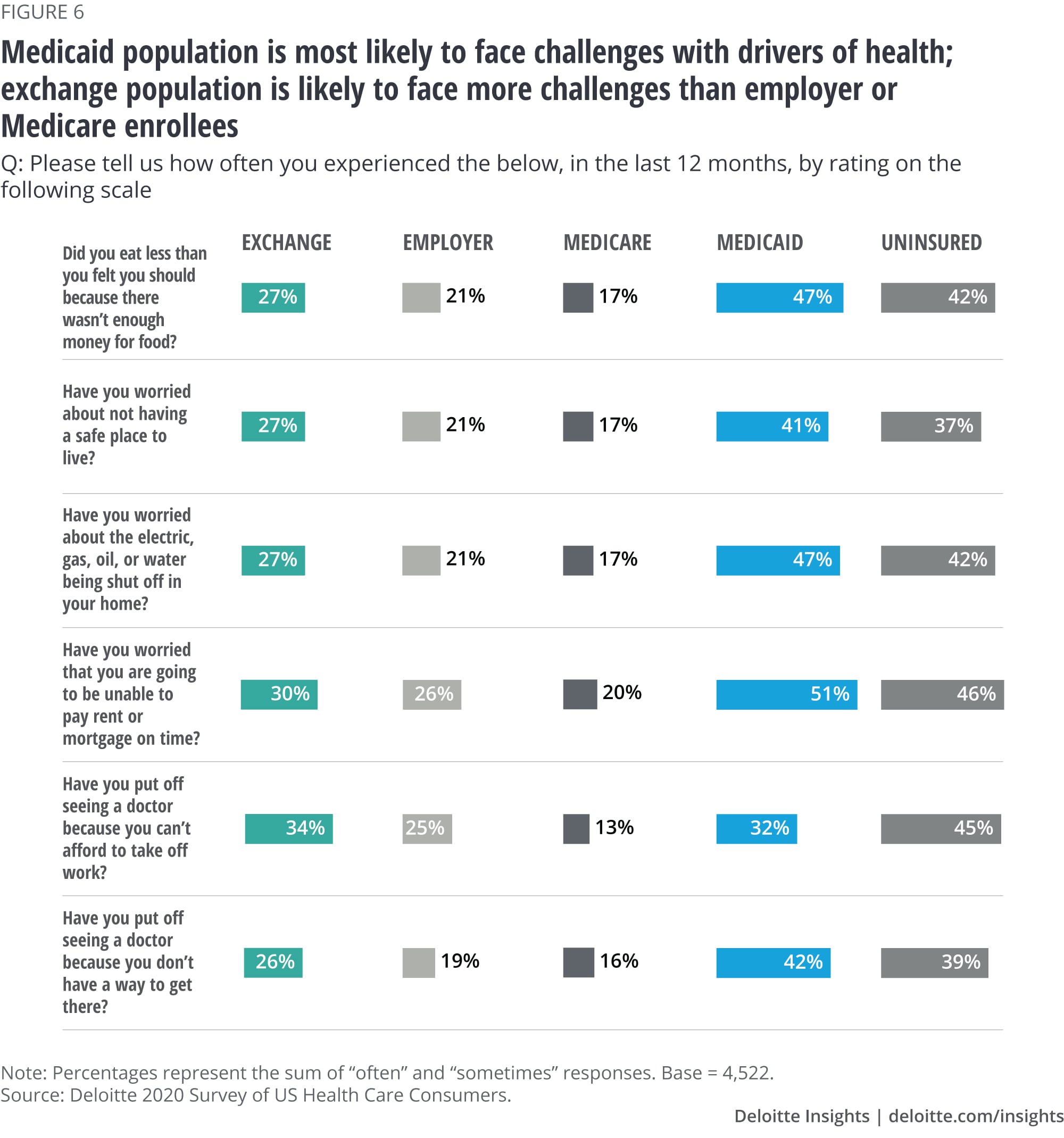

People with all types of health coverage and at all incomes can face challenges with drivers of health— factors outside the traditional health care system that impact our health, also known as social determinants of health. Some of these challenges are especially acute for people with lower incomes. COVID-19 has shone a harsh light on this already salient challenge. In our survey, 84% of Medicaid consumers meet our definition of low-income (having incomes at or below 250% of the federal poverty level), and 41% of exchange consumers are low-income.

Medicaid consumers and those who are uninsured are most likely to say they face challenges with issues such as having enough money for food or to pay for utilities (47% for Medicaid) and being able to pay for housing (51% for Medicaid). Although fewer exchange consumers are likely to say they face challenges with these issues than Medicaid consumers, at least a quarter did report these challenges. With widespread unemployment, these issues are likely to have grown since March (figure 6).

Decades of research has shown that the drivers of health greatly impact health outcomes. In recent years, health plans have implemented programs and partnered with communities to address these factors. We asked our respondents to indicate what services they might be interested in to help support their health beyond doctor visits and traditional care services. For exchange consumers, the most popular service (43%) is one that explains how health insurance works and what services they have access to that could benefit them, followed by a “one-stop shop for physical and behavioral health care” and help with paying bills (39% for each). For the Medicaid population, the most popular services are help with paying bills (51%), followed by the “one-stop shop” (48%).

Mental health issues impact many populations, and some of these problems have been exacerbated by social distancing, economic hardships, and other aspects of the pandemic. These problems are especially common in the Medicaid population. In our survey, we found 71% of people with Medicaid said they sometimes or often felt nervous or anxious, and 65%, sad or depressed. Although the percentages are lower for exchange consumers at 52% and 42%, respectively, these are high relative to most other groups (figure 7).

Our Health Care Consumer Response to COVID-19 Survey, fielded during the pandemic, found that Medicaid consumers were most likely to report that they had felt anxiety or fear “a lot.” Medicaid and exchange consumers were also more likely to report they had felt uncertainty or lack of control “a lot.” Health plans could consider strategies to connect members with services in their community or available to them through their benefits, including virtually. Many members might have access to virtual health options for mental and behavioral health, and consumers might need help accessing those services.

Implications for health plans

As health plans and states consider how to engage exchange and Medicaid consumers, our data finds that these consumers are using and eager to try a wide variety of digital tools. These tools can help in their search for high-quality and lower-cost services, support direct access to providers through telehealth and to other services, make enrollment processes easier and more efficient, and support better health. Not every tool is effective and yields a return on investment, but experimentation and learning how these work from the consumer perspective can be worthwhile.

Deloitte’s future-of-health vision contemplates consumers having agency—empowered to make choices, improve their health, learn about their conditions, and share their data to support insight development. Our focus in this paper on two populations that tend to have lower incomes suggests that there are many consumers in this group who are showing some of the attributes of the envisioned agency.

Medicaid and exchange consumers are more likely to face challenges with the drivers of health, problems exacerbated in today’s economic environment. Many health plans are already working to address these issues with benefit and program strategies, but the need will likely be even greater over the next few years.

Although this article focuses on differences in attitudes by insurance line of business, these groups of people vary on other important characteristics as well. Disparities in health care outcomes by race have been well known for years, and the coronavirus pandemic has illuminated long-standing differences in health status that have made some populations more vulnerable to COVID-19. Type of job and family living arrangements have also played a role.9

As health plans approach all their members, but especially people displaced and challenged because of the pandemic, economy, and social disruptions, they should approach people with empathy and sensitivity—with the goal of helping people feel supported and understood.

Our Health Care Consumer Response to COVID-19 Survey found that 52% of insured consumers say their plan gave them confidence about their safety, 51% say their plan made it easy to understand their benefits related to COVID-19, and 55% say the plan demonstrated an interest in their health and well-being. As consumers begin to re-engage with the health care system, hospitals, health systems, and health plans have an opportunity to remove anxiety and build trust with consumers. Consumers value empathy, reliability, competence, and transparency.10 Focusing on those elements, while questioning long-held beliefs about the health care system, can create a stronger level of consumer trust in health care.11

More on health care

-

The future of virtual health Article4 years ago

-

Medicaid in 2040 Article4 years ago

-

Is the hospital of the future here today? Article4 years ago

-

Health care Collection