Medicaid in 2040 Five big changes

12 minute read

18 March 2020

Medicaid could look radically different by 2040, driven by five major changes.

The future undoubtedly will bring tremendous change to the world of health, and Medicaid is no exception. As described in Forces of change: The future of health, early diagnosis and prevention will become the focus of our health system in 2040, eclipsing the current focus on treatment and cures.1 In some cases, the onset of disease may be delayed or eliminated altogether; cancer and diabetes could join polio as eradicated diseases.

Learn more

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

As the rest of the health care industry transforms, what does this change mean for Medicaid beneficiaries and Medicaid agencies? Medicaid’s mission may still be to improve the health of people with disabilities and lower incomes so they can get the health care services they need, but the way Medicaid accomplishes this will change.

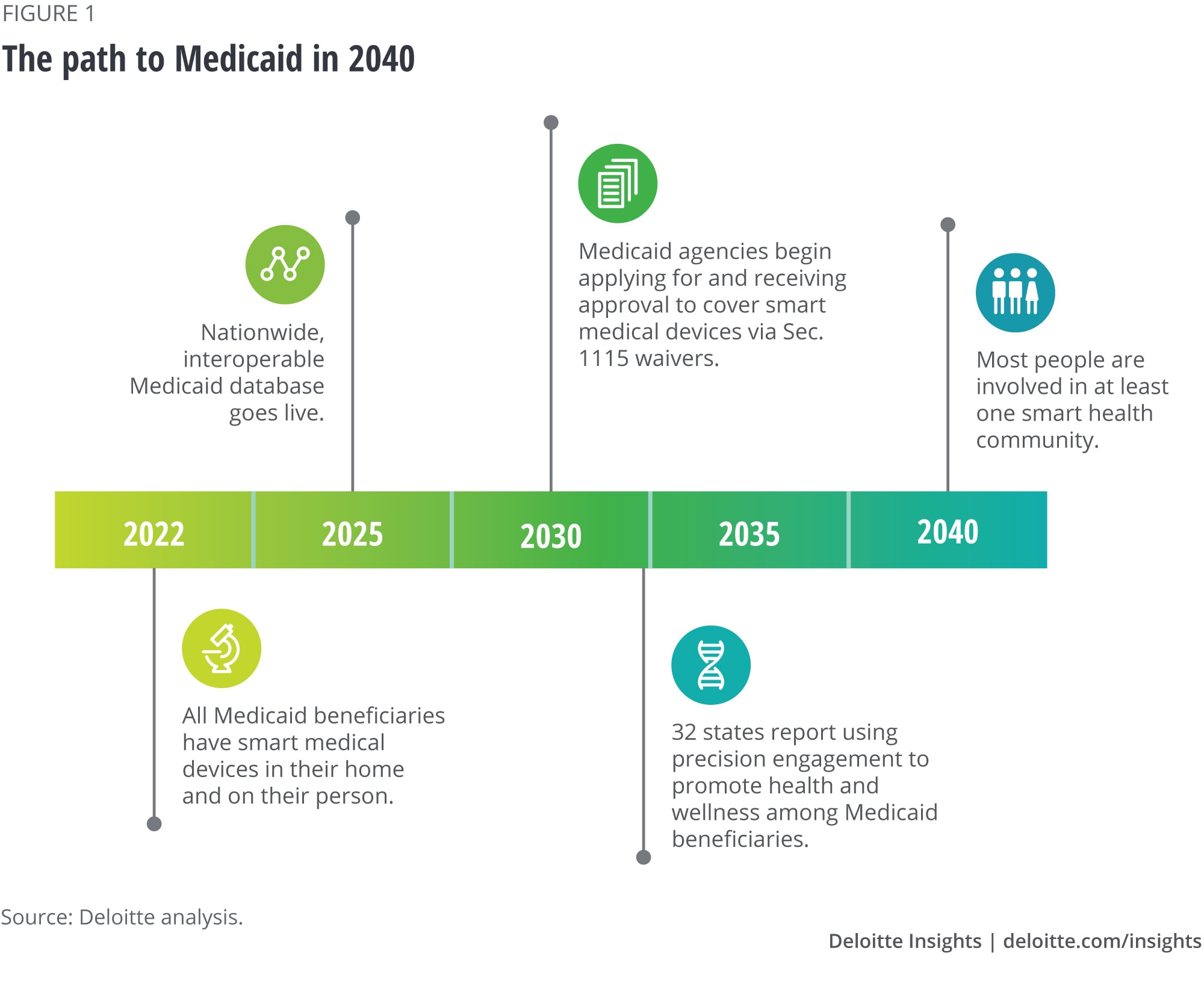

State Medicaid leaders and policymakers are hungry to know what the future of health care holds, so they can prepare their programs for the changes ahead. More importantly, an enhanced understanding of what Medicaid could look like in 20 years can help leaders be more effective today in driving their programs toward the future (figure 1). To build a picture of what the Medicaid world might look like two decades from now, we gathered a group of subject matter specialists with deep knowledge of the larger health care and Medicaid ecosystem. While no one can precisely predict the future, we asked this group to imagine a possible future; what follows isn’t a definitive prediction of what will happen, but an informed judgment about what could happen. The consensus was that five big changes could impact Medicaid and its beneficiaries in 2040:

- Smart medical devices will be in the hands of all Medicaid beneficiaries, empowering them to manage their own health and wellness.

- A nationwide database of Medicaid and health care data will exist, visible to all health care stakeholders, including Medicaid patients.

- Managed-care organizations (MCOs) may not exist in the future; “wellness organizations” may rise in their place.

- Customized behavioral interventions, known as precision engagement, will drive wellness and preventive care.

- Localized health hubs will play a larger role in the health care of the future.

The potential benefit for Medicaid’s roughly 74 million enrollees is significant, as sophisticated tests and tools mean that much prevention and care will take place at home. Health care will increasingly be directed and driven by consumers who are empowered to take control of their own health. Individuals will be at the center of the health model.

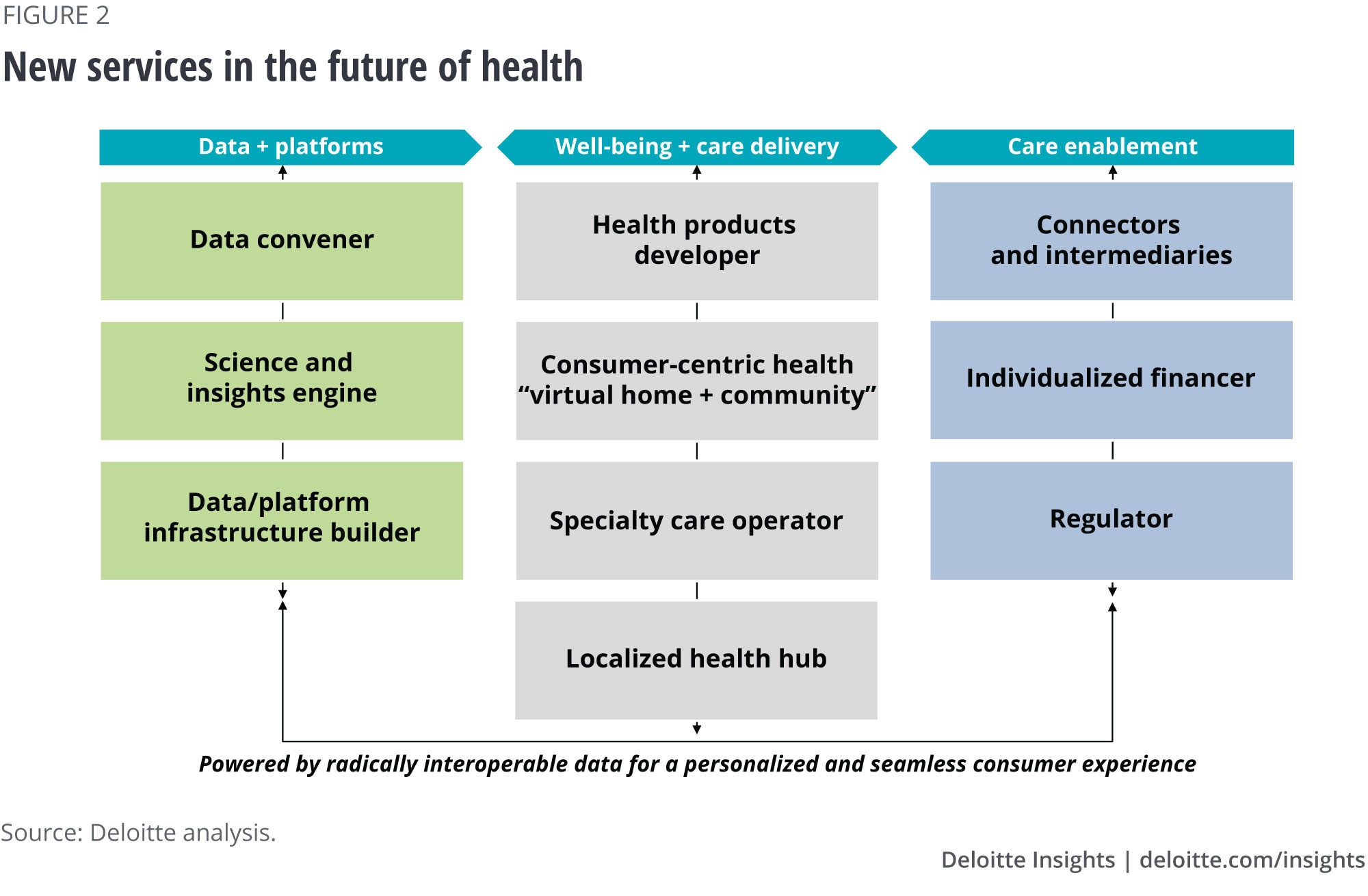

Interoperable, always-on data will promote closer collaboration among health care stakeholders, and new combinations of services will be offered by current providers and new entrants (figure 2). But these changes will require those who administer Medicaid programs to think in new ways to effectively interact with these evolving business models.

1. Smart medical devices will be in the hands of all Medicaid beneficiaries, empowering them to manage their own health and wellness

In the year 2040, all Medicaid beneficiaries will have smart medical devices, both at home and on the go. These devices will be used to:

- Manage health conditions via sensors, telehealth, and remote patient monitoring.

- Provide well-timed nudges that promote healthy lifestyles and medication adherence.

- Foster smart health communities—geographic or virtual communities that leverage data, technology, and behavioral science to provide a sense of community to individuals, empowering them to proactively manage their health and well-being.2

How might Medicaid beneficiaries use smart medical devices in the future?

Racquel is a 32-year-old Medicaid beneficiary who is on maternity leave from her job and home alone with her newborn most of the day. She feels overwhelmed and isolated and has been diagnosed with postpartum depression. Like most people, Racquel has a virtual assistant at home, which she uses for everything from inquiring about the weather to ordering groceries for delivery. Her virtual assistant can also detect changes in her mood, based on the sound and pitch of Racquel’s voice.

Today, the virtual assistant has detected an alarming change in her mood, and alerts Racquel’s mental health provider. The mental health provider reaches out to schedule an emergency video consultation to assess whether Racquel requires in-person assistance or whether her medications need to be adjusted. The 20-minute consultation confirms that Raquel is okay and offers support and mental health strategies, encouraging her to leave the house and attend the local New Moms group with her baby.

The New Moms group, which meets at a local library, is an extension of the virtual group by the same name. It is a smart health community in which new mothers share useful tips about a range of topics, including managing postpartum depression. Data about Racquel’s mood, which is assessed and collected by her virtual assistant, demonstrates that her mood improves when she participates in the group, either online or in person. The virtual assistant often “nudges” Racquel to log into the group’s console when her mood dips below a certain threshold, and it will encourage Racquel to attend an in-person meeting if one is being held that day within five miles of her home.

Will Medicaid beneficiaries across age and eligibility groups have the ability and know-how to use smart technologies?

By 2040, younger Medicaid beneficiaries will be “tech natives”—individuals who have never known life before smart technology. But even people in their seventies and eighties (today’s boomers and Gen X) will have used smartphones and other smart devices for decades, and will be fluent in technology and its many uses. Moreover, technology companies will have developed apps and devices that are tailored to individuals who may have had difficulty using smart devices in the past, including Medicaid beneficiaries who are blind or have motor-skill impairments. There will also be a proliferation of apps that target various Medicaid eligibility groups, including pregnant women, individuals with mental health and substance use disorders, and the elderly, offering new ways for these groups to monitor their own health.

What if Medicaid beneficiaries can’t afford smart medical devices?

States will provide smart medical devices to beneficiaries as a covered benefit. Years of data are likely to show that using smart technologies for preventive health and chronic care management leads to net savings for Medicaid programs. As such, many states will have received permission from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) via Section 1115 waivers to provide smart devices as a covered benefit as early as the year 2030. In 2018, Ohio Governor John Kasich signed the Technology First Executive Order, making Ohio the first state in the country to emphasize expanding access to technology for people with developmental disabilities.3

Will Medicaid beneficiaries be required to use smart medical devices to receive certain kinds of care?

While there will be no requirement that Medicaid beneficiaries purchase or accept smart medical devices as covered benefits, there are many services that will no longer be available in person, both in Medicaid and throughout the health care system. For example, routine monitoring for hypertension, diabetes, and obesity will be conducted via smart medical devices in the home. Relevant data will be transferred to a patient’s primary care clinician, who will do any necessary follow-ups. By and large, beneficiaries will find the services convenient and of high quality, prompting most beneficiaries to proactively embrace them.

2. A nationwide database of health care and related data will exist, visible to all health care stakeholders, including Medicaid patients

In the year 2040, a nationwide database will exist that makes available Medicaid health care and other relevant data. This data will be interoperable among all health care stakeholders—primary care providers, labs, pharmacies, public health agencies, and long-term care providers, among others—and fully accessible to patients themselves. This includes not just health care data but also information on factors such as social determinants of health that can be mined for predictive analytics and more comprehensive health management. For example, connecting data from housing programs and Medicaid could help address the needs of a homeless person with mental health issues.

This database will help improve the quality of care by providing a more holistic view of the patient, reducing inefficiencies and administrative burdens, and aligning financial incentives.

Ethical standards for collecting and using data will have paved the way for the adoption and use of interoperable data systems. The US federal government will have revised the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act to enable data-sharing while also protecting patient privacy. Physician associations will have developed a model for how proactive genetic testing data is incorporated into primary care, while the US Congress will have worked with states to develop standards to govern how and with whom this data is shared. As a result, Medicaid beneficiaries will receive care tailored to their specific risk factors.

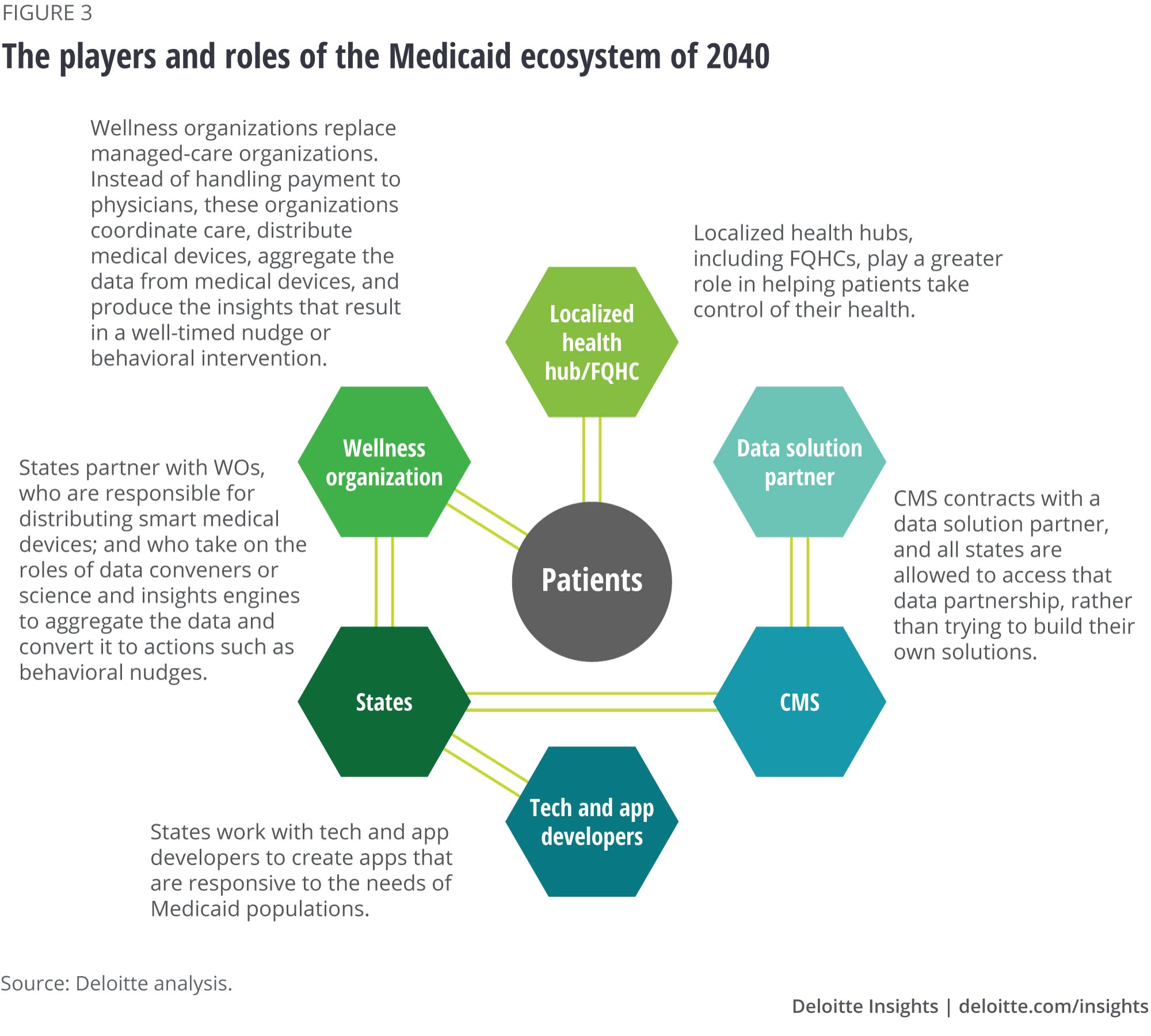

States will be creative at finding ways to convince beneficiaries to share their data. They also will take a bigger role around data convening. For instance, CMS might contract with a data solution partner, and all states will be allowed to access that data partnership, rather than trying to build their own solutions.

With data-sharing in place, state Medicaid agencies are now well-positioned to coordinate with other health and human services organizations as well as community-based organizations to address drivers of health and other areas of health and wellness.

How might Medicaid beneficiaries use interoperable data in the future?

Eric is a six-year-old Medicaid beneficiary who lives with his single mom, Sarah. Eric has an ear infection. Taking Eric to the doctor would mean Sarah would have to miss her restaurant shift to take a bus across town with Eric to the nearest health center. Fortunately, she has other options. Rather than taking him to a clinic or doctor’s office, she uses an at-home diagnostic test to confirm his diagnosis. Open and secure data platforms allow Sarah to verify the diagnosis, order the necessary prescription, and have it delivered to their home via drone. Or maybe the ear infection never materializes because the issue is identified and addressed before symptoms appear. In this case, a prescription might not be needed at all because of the early intervention. This approach empowers Sarah to act quickly and address health issues at home, while allowing physicians to focus on complex cases that truly require human intervention.

3. Managed-care organizations may not exist in the future; “wellness organizations” may rise in their place

Over two-thirds of today’s Medicaid beneficiaries are served by MCOs, which states contract to manage the health care of their beneficiaries. Many MCOs today are part of larger health insurance companies that also serve individuals in the private health insurance market.

In the future of health, health insurance companies likely will not exist as they do now. Advanced risk models will substantially alter the nature of risk pools (a group of individuals whose medical costs are combined to calculate premiums), and prevention and self-management of health will eclipse treatment in medical facilities. Instead of insurance companies, there will be individualized financiers that create specific, tailored, and modular financial products that individuals will use to navigate their care; catastrophic care coverage packages will also be available. Some individual financiers will include noninsurance financing products (for example, loans, lines of credits, and subscriptions).

The changing role of health insurance companies in the private market may lead to other models in Medicaid as well. Instead, a new organization may emerge—the wellness organization (WO). WOs will be in charge of ensuring that Medicaid beneficiaries receive the social services that impact the drivers of health (such as food, transportation, and housing); coordinate care with doctors and hospitals (both in-person and virtual); distribute smart medical devices; and ensure that patients understand how to use these devices.

How might Medicaid beneficiaries interact with wellness organizations in the future?

Doug is a 63-year-old Medicaid beneficiary who is food-insecure. He has lived by himself since his wife passed away two years ago. He earns the minimum wage in an expensive urban center and often has trouble paying his rent and affording groceries at the end of the month. Doug is also diabetic; his condition has been well managed for over a decade with medication, remote-patient monitoring, and the occasional telehealth visit. However, because he is sometimes unable to afford healthy food, he often buys less expensive food that is high in sugar. This causes his blood sugar to rise, countering the positive impact of his medication and the long walks he is prompted to take by his virtual assistant.

When Doug first became eligible for Medicaid several years ago, he was assigned to a WO. The WO screened him for various drivers of health and identified him as being food-insecure. The WO connected him with community-based food organizations, such as area food banks. Now, when Doug’s smart medical device shows a poor nutritional reading for more than two consecutive days, the WO alerts the area food pantry. In turn, the food pantry sends a balanced meal to Doug’s home within four hours. These services are all covered by Medicaid.

4. Precision engagement will drive preventive care

Every Medicaid beneficiary is different. Indeed, every person is different. As such, driving down health care utilization and associated costs via lifestyle changes requires knowing when and how to engage each and every individual consumer. By 2040, this is exactly how Medicaid agencies and WOs will be engaging with Medicaid beneficiaries.

As an analog to precision medicine—which tailors medical treatments to the individual characteristics of each patient—precision engagement combines data science, artificial intelligence technologies and machine learning algorithms, and behavioral science to learn the preferences and decision biases for each individual.4 This science then identifies behavioral interventions most likely to motivate a patient to change a behavior and stay engaged in a treatment protocol. Big data can be used to deliver the right nudge to the right patient at the right time to improve healthy behaviors and adherence to medication or treatment. Just as individuals respond differently to drugs, they will respond differently to well-designed, personalized engagement interventions.

How might precision engagement appear for Medicaid beneficiaries in the future?

David is a 47-year-old Medicaid beneficiary with asthma. David’s state Medicaid agency and WO know a lot about him beyond his demographic and socioeconomic information—his needs, preferences, and behaviors. For example, through many years of interacting with him, they also know that he prefers to receive recommendations through an app rather than his virtual assistant, the progress of his asthma care journey to date, and how he responds to social cues and incentives. They know, for example, that he responds well to competitive incentive schemes, such as those that provide some kind of reward to an individual within a group who makes the most progress toward a particular goal. They also know that he does not respond well to supportive incentive schemes such as “buddy” programs, although his spouse does. This information helps the WO design incentive schemes that help David manage his asthma and many other aspects of his health, and practice preventive health. This precision engagement keeps David healthy and out of the hospital.

5. Localized health hubs shift focus from health care to health

In 2040, most health care that is not delivered virtually will be delivered in localized health hubs that will serve as centers for education, prevention, treatment, and a more holistic focus on health, often in a nontraditional or retail setting. Additionally, localized hubs will connect consumers to virtual, home, and auxiliary wellness providers.

The federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) of today can also be considered a localized health hub of the future. These include community health centers, migrant health centers, health care for the homeless, and health centers for residents of public housing—currently serving more than 27 million people in the United States. They provide care as well as employment to local communities. In addition to physicians and nurses, they are also staffed with social workers and mental health professionals to provide holistic care. They are already integrated into the community today and in the future, with virtual health capabilities, can become more dynamic.

It will be imperative to modernize and strengthen FQHCs and similar safety net providers so that they can serve the most vulnerable Medicaid beneficiaries and play a greater role in the Medicaid ecosystem (figure 3).

How might localized health hubs help Medicaid and public health programs come together in the future?

Helena is a 41-year-old Medicaid beneficiary who recently lost her job. She hasn’t been feeling well for the past few days but has avoided going to a doctor since she has several job interviews scheduled. After finishing one of the interviews, she stops at a local pharmacy and notices that it is a localized health hub. She visits the pharmacy-based clinic and gets help with some diagnostic tests and checks her blood pressure and weight. Helena has high blood pressure and has been stressed since she lost her job. She knows she hasn’t been eating right or managing her condition well. Using one of the tablet computers in the hub, she learns more about managing her condition and downloads a mobile meditation app for reminders and tips on managing stress on the go. She also signs up for a virtual session with the in-house diet counselor.

Looking ahead

The next two decades are sure to bring many changes to the Medicaid program. By peering into the future, however imperfectly, program administrators may be able to see possibilities that aren’t readily apparent when dealing with day-to-day challenges.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More about health care and the public sector

-

Smart health communities and the future of health Article5 years ago

-

Social determinants of health for Medicare, Medicaid enrollees Article6 years ago

-

Social determinants of health and Medicaid payments Article6 years ago

-

Innovation in the Military Health System Article6 years ago

-

Medicaid and digital health Article6 years ago