Pathways to the university presidency has been saved

Pathways to the university presidency The future of higher education leadership

18 April 2017

The dynamics of higher education in America today are driving the demand for a new set of skills and capabilities for tomorrow’s leaders. Learn how the role of college president is being transformed, the reasons behind these changes, and what the future implications may be for universities.

Key highlights

Learn More

Explore the Higher Education collection

The role of the college president has no analog in the modern business world.

It is accountable to a dizzying array of stakeholders and constituents, on campus (students, faculty, and administrative staff) and off; parents who are hyperinvolved in every aspect of their child’s experience; community leaders seeking to influence the university’s role in town; alumni who want to maintain the experience they had as students; and, in the case of public institutions, political leaders who demand greater accountability even in the face of dwindling state support.

The job requires administrative and financial acumen, fundraising ability, and political deftness. Presidents must be accessible and responsive but also measured and restrained in an era driven by 24/7 news coverage and the inflammatory nature of social media. They often need to balance the pressures of society to improve the “return on investment” of education at their institution as well as manage the pressure from community and political leaders around critical issues such as sexual assault and legalized guns on campus. Presidents must chart a difficult path with their academic deans, providing incentives for individual schools to excel and grow while fostering collaboration and cooperation with each other to drive the overall health of the academy.

The range of leadership skills with which they surround themselves is vast—athletics, academics, finances, marketing, fundraising, and research to name just a few, all housed within a model of shared governance that could drive almost any traditional business leader to distraction.

In this look at the college president, we examine what it’s taken to be effective and excel in the role today, and how the dynamics of higher education in America are driving a new set of skills and capabilities for tomorrow’s leaders. Deloitte’s Center for Higher Education Excellence, working in partnership with Georgia Tech’s Center for 21st Century Universities, conducted this study through a combination of an extensive survey, in-depth interviews, and the first-ever analysis of presidential CVs. Among the highlights of our findings:

Varied pathways. While the provost’s office has long been the most frequent stopover point on the way to the presidency, the paths prospective presidents now take are becoming more complex, fragmented, and overlapping. Academic deans are increasingly moving right to the top job and bypassing the provost’s office altogether. This is particularly the case at small colleges, where the institution as a whole is akin to the dean’s job at a large university.

A new role for the provost. The provost is no longer simply regarded as the No. 2 person on campus. Rather, today’s provosts often have a set of skills that complement the president, rather than replicate them. The shift in responsibilities means that the provost’s role might not always be the best preparation for the presidency, especially if the provost is involved primarily with academic affairs and internal issues.

President as fundraiser-in-chief. Fundraising is essential from a president’s first day in office, according to the survey, and only grows in importance over time in the position. But that doesn’t mean presidents are ready and willing to take on fundraising tasks. Despite the attention given to this issue over the past several years, preparing presidents to cultivate donors hasn’t improved much, if at all.

A need for formal leadership development. Investments in leadership often lag behind their importance to presidents. While nearly two-thirds of presidents surveyed said they had coaches or mentors to help them prepare for the role, only one-third indicated that they still receive coaching to succeed in the job. Presidents identified leadership development as the second most important professional training opportunity needed on the job (after fundraising).

Emphasis on short-term wins at the cost of long-term planning. There is increasing pressure on presidents to look for quick wins. As a result, many are looking for the proverbial low-hanging fruit on their campuses where they can show fast results, not only for their own boards but also for search committees for their next job.

Even without the pressures bearing down right now on higher education, many college presidents are likely in the final years of their tenure, given the demographics of those currently in the top job. A wave of departures is expected to come among presidents over the next few years. Where their successors will come from remains a key question for governing boards and other key stakeholders on campuses. What follows is a primer to help leaders recognize the challenges they may face and how to potentially rethink leadership for higher education in the 21st century.

Introduction

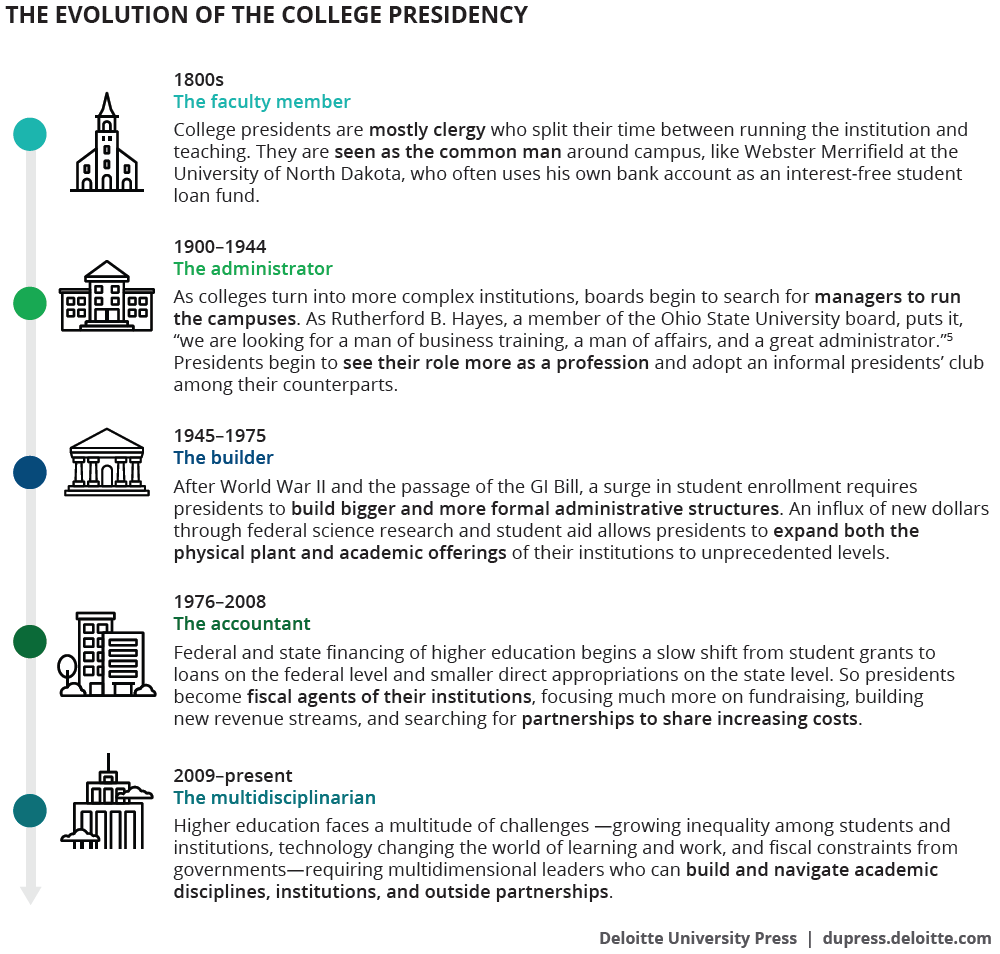

While college presidents these days are often compared to corporate CEOs, for much of the early years of American higher education they were often seen as little more than an extension of the faculty. Most presidents were clergymen who regularly taught classes, rarely traveled far from the campus, and even prided themselves on knowing every student by name.

At the turn of the 20th century, the college presidency started to take on an expanded role, as institutions increased their academic offerings. Out went the ministers as presidents and in came more professional administrators. When John H. Finley was announced as president of City College of New York in 1903, he received a letter from the University of Chicago’s president assuring him that while “there are plenty of men to be professors; there are only a few to be presidents of colleges and universities.”1

By the 1930s, a book about college presidents described the job as “the business manager of a great plant, a lobbyist often at the general assembly of the state… and a peripatetic raiser of funds.”2 The decades after World War II—with the arrival of Baby Boomers to campuses and new federal spending with the onset of the Cold War—marked a new role for presidents as dominant figures in higher education’s expansion. Indeed, during this era two giants of the college presidency rose to power—the University of California's Clark Kerr and the Rev. Theodore Hesburgh of Notre Dame.

The economic slowdown of the mid-1970s, and the resulting cuts in federal and state higher-education spending, meant that college governing boards started to look for leaders who could be better fiscal managers and, increasingly, fundraisers. In 1976, Kerr would describe presidents hired in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s as “kind of out of date,” adding the presidential type now needed was a “a kind of super-accountant.”

It was in these waning years of the 20th century that the college presidency began to turn into more of a profession sought by academics who switched jobs every few years and navigated through campus bureaucracies to better learn how to run complex institutions. Searches for presidents grew longer and more extensive and were managed by executive search firms that increasingly focused solely on higher education.

In 1986, the American Council on Education (ACE) published its first study of the college president. It found that campus leaders were mostly white males in their early fifties.3 Four in ten presidents at the time were in their forties, and most came to the position through the provost’s office.

In subsequent surveys since then, ACE found that little has changed about the people holding the top job on campuses—except they are graying and not staying in the role as long. Nearly six in ten presidents are in their sixties and their average tenure in the job is seven years, down from eight and a half years a decade ago.4

A pipeline running dry

What’s worrisome about these trends is that the traditional pipeline to the job risks running dry in the decade ahead, as the enormous demographic and financial challenges facing institutions intensify. Not only are presidents aging, but public flameouts are ending their tenures early. Several presidents have faced high-profile ousters in recent years.

Where their successors will come from is more of an open question among search committees than ever before. While the provost’s office remains the most common launching pad for presidencies, there is evidence from surveys of sitting provosts that many no longer aspire to the top job, nor in some instances have the broad set of skills necessary for the changing demands of the role.

Much like at the turn of the 20th century and then again in the 1970s, the college presidency today is in a state of change. As institutions look to hire the next generation of leaders, what skill sets should they be looking for? Where will presidents come from in the future? What training will they need to succeed and thrive in the top job?

This report aims to answer those questions and more with the results of a groundbreaking study on the future of the college presidency. In 2016, Deloitte’s Center for Higher Education Excellence and Georgia Tech’s Center for 21st Century Universities embarked on nearly a year of research that included a survey of more than 150 current four-year college and university presidents, in-depth interviews with two dozen presidents and trustees, and data mined from more than 800 CVs of sitting presidents of four-year colleges to get a better sense of their career paths.

Our hope is that this study informs planning for trustees and college executives as they grapple with the coming leadership changes and provides a roadmap for how higher education can better prepare and select its next generation of presidents.

Methodology

Planning for this report began in the spring of 2016, as a joint project between Deloitte’s Center for Higher Education Excellence and Georgia Tech’s Center for 21st Century Universities.

The initial phase included a literature scan of previous research on the state of the college presidency, in part to inform a survey of college presidents that was fielded in August 2016. We would like to thank the following individuals who provided their insight and expertise on the survey questions: Scott Cowen, Richard Ekman, Wes Moore, Carol Quillen, Shelly Weiss Storbeck, and Diana Chapman Walsh.

Surveys were sent via email to 1,031 presidents of four-year colleges and universities. Completed responses were collected from 165 presidents, yielding a 16 percent response rate. Respondents represented 112 private institutions and 51 public institutions.

For the CV analysis, data was collected on 840 presidents, gleaned from publicly available information on institutional websites and through other sources, such as LinkedIn. The following students at the Georgia Institute of Technology assisted in the CV analysis: Rebecca Hull, Jing Li, Sarah Scott, and Lu Yin.

Presidents and trustees—from a diverse representation by geography, institution type (public, private), campus type (single, multiple, online) and student body size—were interviewed by authors and a note-taker from Deloitte between January and March 2017. All interview subjects were offered anonymity to allow them to be frank in our conversations. Some waived the offer, but most of the quotes presented in the report from those interviews are without attribution to maintain consistency.

The changing presidency

A hundred years ago, the college presidency was described by academics as a “club” in which members had a similar pedigree and recognized the problems each other was dealing with on their campuses.5

The modern college presidency lacks any sort of cohesion.

Our study found that fewer college leaders arrive at the top post in the same way as in the past or agree on the issues that face their campuses. How presidents define their role largely depends on the type of institution where they serve (research university vs. liberal arts college or public vs. private), how long they’ve been in the job, and the route they took to get there.

While the provost’s office has long been the most frequent stopover point on the way to the presidency, the paths prospective presidents now take are becoming more complex, fragmented, and overlapping. Two primary developments seem to be responsible for these varied routes:

Academic deans are increasingly moving right to the top job and bypassing the provost’s office altogether. This is particularly the case at small colleges, where the institution as a whole is akin to the dean’s job at a large university. Deans these days are essentially mini-presidents and are seen as academic entrepreneurs on campuses with decentralized budgeting models. What’s more, they frequently work with advisory boards and are prodigious fundraisers who oversee thousands of students.

The president of a small, liberal arts college told us that the route from dean to president is a recognition that higher education’s often lengthy and sluggish climb to the top of the organization doesn’t work for a new generation of leaders.

“Highly creative people need faster paths, or they are going to go elsewhere to find them,” the president said. “It is difficult to speed up the traditional route. We need to find ways to promote people more quickly, and need quicker paths to the presidency than provost.”

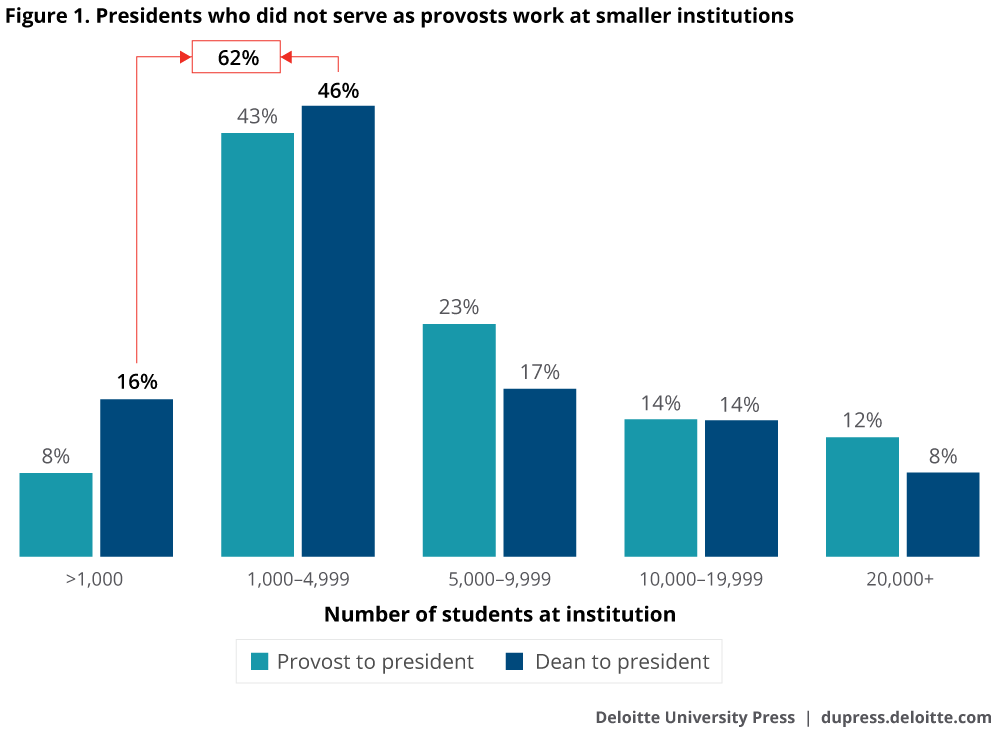

Of the presidents in our CV analysis who never served as a provost, two-thirds lead institutions with fewer than 5,000 students (see figure 1). Those who went right from dean to president are newer to the job than those who were provosts first, indicating that this pathway is likely a more recent trend.

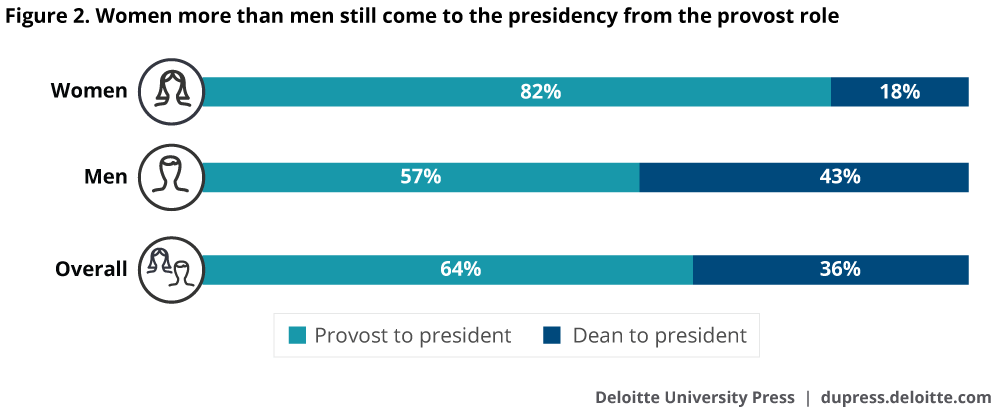

There is also a significant gender gap between the traditional provost pathway and the fast track from dean (see figure 2). It’s much more common for women to stop at the provost’s office on their way to the presidency. According to our study, three times as many men as women went right to the presidency from the dean’s office.

- The provost is no longer simply regarded as the No. 2 person on campus. Rather, today’s provosts often have a set of skills that complement the president, rather than replicate them. There is a “bit of separation occurring between the provost and the president,” a trustee at a large public research university told us. The provost is focused “inward and down,” working with faculty and students on the academic experience. Meanwhile, the president is looking “up and out,” focused on relations with the governing board, the public, alumni, and in many cases, political leaders.

This external focus is a critical role for a contemporary president to play in a day and age when social media can turn a minor dustup into a national story and impact an institution’s brand almost overnight. The “president owns the brand and the larger experience of ‘the university,’” the trustee said.

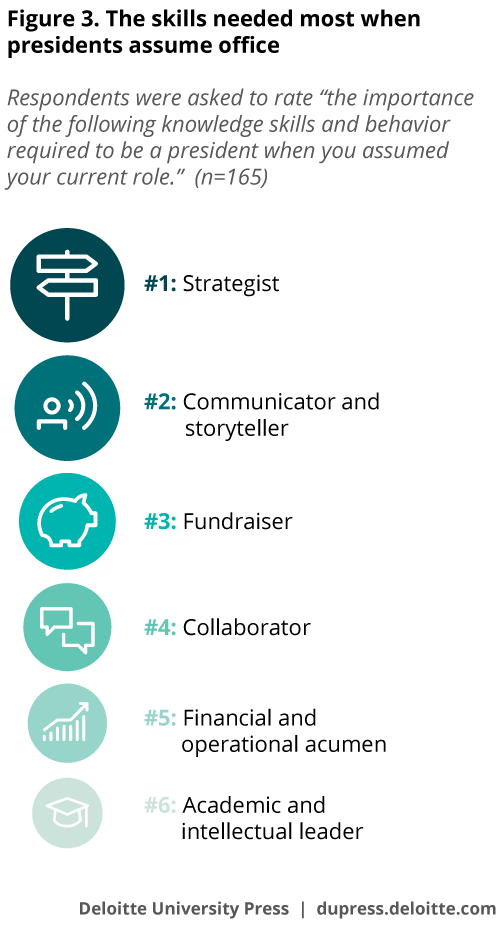

The shift in responsibilities means that the provost’s role might not always be the best preparation for the presidency, especially if the provost is involved primarily with academic affairs and internal issues. In our survey, presidents told us that being an “academic and intellectual leader” ranked last among a set of skills and behaviors most needed when they assumed office. At the top of the list: strategist, communicator, and storyteller (see figure 3).

“Universities have big goals and big aspirations, but can be very linear places with very incremental strategic plans,” said the president of a large, public land-grant university. “They need nonlinear planning and a strategy mind-set to reach big goals.”

The way presidents view the skills required for the job differs depending on how long they’ve been in the role.

In general, veteran presidents surveyed tend to think of higher education as a collegial, intellectual community where they are the academic leader. New presidents, meanwhile, see themselves through a financial and operational lens and as a leader who needs to get things done despite the collaborative nature of campuses—a CEO role, not in the top-down sense, but rather a general manager surrounded by a skilled executive team.

These often opposing opinions of the campus leadership role influence the competencies presidents think are required for the job and who they believe will fill their offices in the future. Presidents in the job for more than 15 years value academic and intellectual skills and consider the provost as their likely successor; presidents with less than a decade of experience say financial and operational acumen is most important and say the person next in line for the role will most likely come from the private sector (see figure 4).

Best prep for the presidency? Take on a range of extra work

During our interviews, we asked presidents about the advice they would give to others seeking the role. Here’s what an experienced president of a large urban public research university told us:

- Seek breadth and depth. Get the broad experiences to understand how universities work. “Amazing what you can learn doing things nobody else wants to do,” the president said.

- Look outward. Gain experience working with external partners and relationship building. “As president, you're the external person, not internal.”

- Acquire budget experience. Money is the critical tool to realizing any plan as president.

Here are three ways this campus chief told us that great leaders differ from the good ones:

- Pay attention to the culture and process. “They matter a lot. If you get the process right, you can do anything.”

- Be a planner. “Remember, you’re always playing chess. Must always be thinking three moves ahead.” Don’t move from one press release to another. “That means you are reactionary. Publicity will follow if you’re being strategic.”

- Have a goal and a pathway to get there. “If you don't know where you're going, you'll end up somewhere.”

President as chief fundraiser

Where there is agreement among presidents—no matter the size of the institution or their tenure in the position—is on the outsized role fundraising plays in their job and how many of them still feel unprepared for it. Clark Kerr first recognized the need for the president to be chief fundraiser in the 1970s, when state and federal support for higher education began to wane.6 The trends Kerr identified have only accelerated since then, and, in many ways, have been made worse by the flatlining of wages in the United States that have made it difficult for even middle-class families to afford rising tuition prices.

Presidents told us in our survey that “fundraising/alumni relations/donor relations” and “strategic planning” rank as the most important responsibilities in their day-to-day job (see figure 5). Fundraising, in particular, is essential from a president’s first day in office, according to the survey, and only grows in importance over time in the position.

But that doesn’t mean presidents are ready and willing to take on fundraising tasks. Past surveys of presidents dating back more than a decade have diagnosed the gap between the importance of fundraising in the top job and the lack of training for it. The results of our survey show that despite the attention given to this issue over the past several years, preparing presidents to cultivate donors hasn’t improved much, if at all.

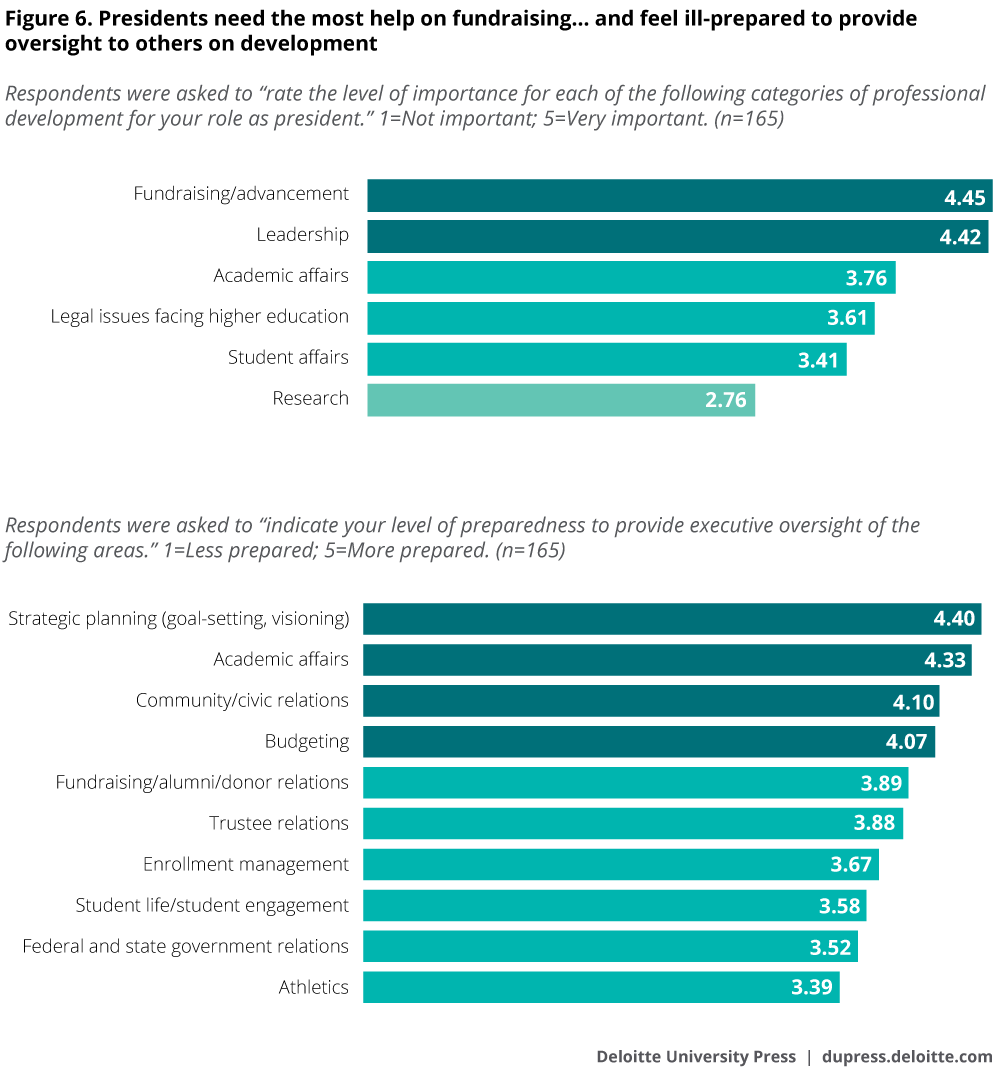

Indeed, in our survey a wide gap existed between the perceived importance of fundraising to a president’s professional development and the ability of the campus executive to provide oversight of fundraising. When asked in the survey to gauge their preparedness to provide oversight on a range of campus issues, presidents ranked fundraising and alumni/donor relations sixth out of ten—below strategic planning, community relations, and budgeting. No wonder presidents said fundraising was the most important skill needed for their professional development (see figure 6).

Preparing for the presidency

Unlike chief executives of Fortune 500 companies who tend to go to business school and are groomed by organizations for the top role, historically being a college president has involved mostly on-the-job training. When institutions were smaller and less complex, presidents could easily move up from the faculty to lead the campus with little instruction. But today’s challenging higher-education environment requires leaders who are adept at navigating various stakeholder groups through a period of rapid change.

Survey of university presidents

Deloitte’s Center for Higher Education Excellence sent a survey via email to 1,031 presidents of four-year colleges and universities. Completed responses were collected from 165 presidents, yielding a 16 percent response rate. Respondents represented 112 private institutions and 51 public institutions. This interactive graphic depicts some of the insights gleaned from Deloitte’s analysis of the survey data, and allows users to explore and create their own customized views.

Even so, no formal training regimen exists to prepare for the presidency. Our survey found that investments in leadership often lag behind their importance to presidents. While nearly two-thirds of presidents in the survey said they had coaches or mentors to help them prepare for the role, only one-third indicated that they still receive coaching to succeed in the job.

Presidents surveyed identified leadership development as the second most important professional training opportunity needed on the job (after fundraising). “Leadership development is stigmatized in higher education,” the president of a public university told us. “There is knowledge out there that can help people become better leaders, but it’s vilified among faculty members who don’t understand it.”

Compare the attitudes toward leadership development in higher education to the corporate world, where, in a survey of 10,000 HR and business leaders by Deloitte, 78 percent identified leadership development as the top issue for companies around the world. Some 84 percent of global organizations offer formal learning programs for leadership development, and US companies spend more than $31 billion on leadership development programs annually.7,8 According to Deloitte’s research, leading organizations invest significantly in leadership development by:

- Employing a leadership strategy aligned with the vision and objectives of the business

- Leveraging a data-driven, evidence-based approach to identify leadership potential

- Providing intensive coaching and continuous development experiences at all levels of the organization

By taking these steps, organizations are able to reap the following benefits:

- Clear articulation of the experiences, exposures, expertise, and expectations of effective leaders

- Earlier identification of high-potential talent for development and selection

- Measurable returns on investment spent developing high-potential talent

Companies that demonstrate the highest maturity level in leadership development are 10 times more likely to be highly effective at identifying effective leaders than other organizations.9 High-maturity organizations approach succession management at multiple layers of the organization, not just the top, and approach succession as a continuous process rather than an activity or event.10

Throughout our interviews with presidents, they often reminded us that the leadership track in higher education is too often seen as a step back from the primary goal in academia: teaching and research. “Colleges are among the few places where taking a leadership position is tantamount to going over to the dark side,” the president of a private research university told us.

Five practices for creating an effective leadership development ecosystem

Effective leadership development occurs not just in training sessions, but also within the business context. No matter how sophisticated an organization’s leadership programs, if the day-to-day workplace does not support leadership development, such efforts will likely produce limited returns.

Up to now, organizations have focused primarily on training the “fish”—the individual leader or high-potential candidate—but have neglected the “pond”—the organizational culture and context—in which the fish swims.

Research by Deloitte shows that organizations that create a “pond” conducive to leadership growth are more likely to grow “larger fish”—stronger leaders—and achieve stronger business results. Leading organizations do this by implementing the following practices:

- Communicating the leadership profile. When you define what the organization stands for, and which capabilities enable leaders to execute the strategy, that helps set expectations for what leadership should look and feel like. Leaders should work together to communicate the capabilities, behaviors, and attributes leaders should display. Such stories form the basis for identifying and developing future leaders, and building the leadership pipeline.

- Cultivating a culture of risk-taking. To work effectively in fast-changing environments and technologies, budding leaders must learn to take appropriate risks. But the ability to take risks is influenced by the level of risk tolerance in the workplace. An organization that is mature in its approach to leadership will encourage individuals to explore new concepts and ideas every day. In an organization that rewards risk-taking, and recognizes that failure provides valuable lessons, leaders feel encouraged to explore, innovate, and build teams to exploit new ideas.

- Sharing knowledge for leadership development. To stay competitive, leaders should be aware of what’s going on in the larger organization and beyond. Leaders grow best in a culture where knowledge flows freely. Sharing information about new offerings and services, personnel decisions, or customer feedback in other areas of the organization helps people develop a deeper understanding of the business. It also gives them greater exposure to what is percolating in the organization and broader market. Equally important, when people hear about shared successes and failures, they gain new insights into the activities of leaders and their decision-making processes.

- Exposing leaders to each other and to enriching experiences. The most effective way to develop new leaders is to expose them to peers and colleagues, as well as to customer feedback, new external contexts, and social networks. Coaching and mentoring are common ways to expose high-potential leaders to diverse challenges and solutions. Another key practice is to provide an external perspective—for instance, through leadership consortia, externships, or shadowing programs that expose people to the needs of the organization’s customers and partners.

- Creating strong ties between HR and business leaders. In organizations that are high in leadership maturity, HR uses its expertise in leadership development to collaborate closely with business leaders. Those leaders, in turn, apply and model leadership learning in the workplace. These “power teams” coordinate development efforts, ensure that business leaders go beyond passive sponsorship, and actively work to promote the growth of other leaders. The contact does not always have to be initiated by HR—it can also be brought about by business leaders helping HR.

Source: Andrea Derler, Anthony Abbatiello, and Stacia Sherman Garr, “Better pond, bigger fish: Five ways to nurture developing leaders in an ecosystem for growth,” Deloitte Review 20, January 2017, /content/www/us/en/insights/deloitte-review/issue-20/developing-leaders-networks-of-opportunities.html.

Future challenges for campus leaders

Presidents are in the midst of a period of rapid change with new challenges coming from nearly every corner of campus. Institutions are welcoming student bodies that are more racially and ethnically diverse than any cohort of students higher education has previously served, and many are arriving with enormous financial need. Technology is transforming how prospective students evaluate and select an institution, how they interact with their peers and faculty, and how faculty provide instruction. Globalization and automation are prompting debates about the very nature of what students need to learn to compete in a new economy.

Many presidents may be in crisis mode or know their next misstep might lead to the end of their tenure. The increased professionalization of the presidency could also mean that many executives expect to lead multiple institutions by the end of their careers.

The ever-changing demands on college presidents and the ambitions of the men and women holding the job are beginning to shift our understanding of the elements necessary to have exceptional chief executives. Our research uncovered four key challenges in play between higher-education institutions and their top leaders that often turn into barriers to successful presidencies:

Short-term thinking. In our interviews, we found increasing pressure on presidents to look for quick wins. As a result, many are looking for the proverbial low-hanging fruit on their campuses where they can show fast results, not only for their own boards but also for search committees for their next job.

“Presidents approach their job with the expectation that they’ll be judged on what they can finish,” said the president of a private university. “They think, ‘I’ll only be here five years, so I should only focus on what I can do in that time before I move on.’ They run their schools like pseudo-corporations. It’s short-term thinking. You might satisfy the immediate issue of the day, but this is unsustainable as a model.”

This short-term thinking surfaces in a variety of ways, including academic programming tied to the current job market; technology purchases that simply patch rather than solve problems; enrollment plans that ignore demographic shifts among students; fundraising that focuses on immediate dollars rather than building a pipeline for future commitments; and strategic plans that are completely rewritten each time a new president is installed.

“Presidents need courage to make bets on the long term, while telling the short-term story that creates ongoing support they need,” said the president of a public land-grant university.

Bad fits. The revolving door among presidents means that colleges and universities are looking for presidents more often. In this war for talent, search committees often have outsized ambitions about what they want in their next president, and this lack of alignment tends to lead to bad fits with hires who last only a few years on the job.

A trustee at a private institution that recently hired a president said that while the pool of candidates was “generally good,” he was “surprised that not everybody had all the experiences we were looking for. We did have a few presidents in the pool, but not as many as I thought we would. We thought we would see more wanting to move up the scale. What we had were lots looking at this opportunity as their first-time position.”

Often the market of available candidates is unable to support the aspirations of the search committee or the institution is looking for the wrong kind of president for its most pressing problems.

The president of a private university told us he recently received a call from a search committee looking to hire a president who would turn the university into a national brand. “I know the last president was fired,” the president said. “The individual really sold the opportunity. Selectivity and tuition discount rates were suboptimal for what they wanted to do. He should not have been speaking about his institution in the way he was.”

One attribute of effective presidents is that they are in sync with the DNA of their institutions. But the career climbers among academic administrators too often apply for presidencies at a range of disparate institutions with varying missions and needs because they simply want to be a president somewhere.

Are presidents prepared for a new era of student activism?

In recent years, colleges across the country have been roiling with student activism that is largely unfamiliar to presidents who came of age during the student protests of the 1970s, a different kind of era. A number of presidents have been caught up in high-profile debates with students, and a few have been forced to step down as a result.

Today, students—and their parents—tend to view themselves as customers who are always right, especially as the price of higher education continues to climb. What’s unclear is whether presidents are prepared to manage this new generation of students.

In our survey, presidents ranked “student life/student engagement” No. 8 among a list of 10 areas of responsibility in terms of their level of confidence in providing executive oversight.

In many ways, their lack of confidence is a reflection of the importance of student affairs in a president’s daily life. When asked about the most important responsibilities in their current role, only 2 percent of presidents ranked “student life/student engagement” among their top three (only athletics ranked lower).

But several presidents said during our interviews that leaders who ignore the will of students do so at their own peril. “We need to have a profound interest in the role that students play,” said the president of a private university who still teaches once a year to stay connected to the issues facing students.

“Presidents sometimes are tone deaf to the needs of students,” the president said. “Some don’t like spending time with them, and they rely on their senior team to tell them what’s going on. That’s not sustainable. We need to be able to understand ourselves what’s happening in our community.”

A longtime president of a large public university told us that he always wanted to lead a land-grant institution but that many of his counterparts lack a guiding ideology about the mission of their campuses. “That’s how you end up with bad fits—a private university provost becomes president at a public land-grant, for example,” the president said. “Even if you’re a wonderful person and an accomplished leader, if you’re a bad fit, you won’t be successful.”

This is particularly relevant to search committees looking for nontraditional candidates who often don’t have experience working in higher education. In our survey, sitting presidents overwhelmingly agreed that campus chiefs need to have previous academic experience. Only 14 percent said private sector or business candidates would be the right fit for their institutions. As one president of a private university told us, the most successful presidents “have a profound respect and belief in the very idea of the university.”

“If you come in with the mind-set that they need to be disrupted, it won’t work,” this president explained. “We are limited by the kind of institutions that we are. We have a thousand-year trajectory that we have to look at, while always acknowledging that there is new technology and new approaches to what we do.”

Good presidents vs. great presidents. Institutions are increasingly looking for transformational leaders to either take a campus to “the next level” or fix long-standing problems. Great leaders are often described as powerful, stimulating, and exciting. They energize campuses with inspiring narratives. But that doesn’t mean they need to be dominant leaders with the loudest voice, said one president at a public university.

“I personally admire administrators who are deft, who have the ability to handle a problem without broadcasting it to the world that they have a problem and how they are handling it,” they observed. “The best presidents solve the problems that no one ever sees.”

The question for presidents and boards is how fast leaders should move on an agenda. “Academics has a natural ‘constrainer’ feature built in—peer review, shared governance,” said the president of a public land-grant university. “Presidents have to know this and be able to successfully navigate with and against it.”

Various stakeholder groups also have strong opinions about what a new president should do the first day on the job. Presidents are hired in part on the vision and ideas they articulated during the interview process, but then they arrive on a campus that already has projects and plans in progress. The newly installed leader and the board “need to do a careful dance” about priorities, a relatively new president at a small liberal arts college told us. “Boards do a president a real disservice when they hand over strategic plans to be executed. Presidents are not CEOs, their power is more diffused, and they have to get buy-in.”

Great presidents usually spend time setting the groundwork for change before turning into a more disruptive force. Other times presidents need to stabilize the programs or finances before moving on to tackle strategic issues.

Both approaches call for leaders who can stay long enough to have multiple phases to their presidencies. John DeGioia, the president of Georgetown University, is an example of a leader who spent his first years in office balancing the university’s books. DeGioia then turned in recent years to extending the institution’s international reach and global brand while overseeing a $1.67 billion capital campaign.

“I was in a turnaround, but once things started getting better, expectations changed,” he said. “Presidents need to resist the urge to rush. It is very hard to guide these places through the disruptions.”

According to the president of a large public university, this ability to shift between short-term demands and long-term strategy separates great presidents from good presidents: “Pressure is often focused on achieving short-term goals—good presidents achieve these goals—great presidents find ways to build long-term capacity and success in the institution.”

The search process. Our interviews generated plenty of criticism about the search process for presidents, and whether the system as currently designed produces the best candidates.

For one, boards and search committees often look for new presidents in response to a controversy stirring on campus or to find a leader with a contrasting style to the one being replaced. A president who works in a large state university system told us that an uptick in student activism recently has meant that leaders with backgrounds in student and legal affairs are popular picks right now, “even though the situation campuses are facing is a narrow aspect of the president’s job, and may be temporary.”

Second, search committees are, at times, designed to fail. In an effort to give everyone a voice in the process, committees usually include a mix of diverse constituencies—faculty members, students, and trustees. While the group might come to an agreement in drafting a prospectus about what it wants in the next president, many times people on the committee end up evaluating candidates through their own position in the institution’s structure. So committees cast a wide net for candidates, even embracing nontraditional applicants, but in the end compromise on the least offensive hire.

Third, few people on the search committee understand the job they are trying to fill. “This is one of my particular beefs about the search process,” the president of a large public university told us. “They conjure up what they think are the most important qualities, and that’s why candidates probably all end up looking identical after a while.”

A matter of debate: Succession planning in higher education

Nearly three-quarters of presidents in our survey said they have not identified potential successors. As the tenure of presidents gets shorter, the need to launch a new national search every time a president departs could impede institutional momentum.

The solution increasingly suggested by board members is for higher education to take a page from the playbook of the corporate world and create a de facto CEO succession plan for college presidents. A survey by InterSearch found that 74 percent of North American companies have a succession plan for their top executive.11 Research by DDI shows that it takes less time for leaders promoted internally to be effective compared with those from the outside. What’s more, it takes externally hired leaders two years to catch up to those promoted internally.12

One trustee at a university whose president stepped aside suddenly told us the “board was left scrambling and had to turn to someone who didn’t want the job.” As a result, the board put in place succession planning as part of its review process for the new president. “Institutions need to know who is up next for president and provost,” the trustee said.

While succession planning has become more common at large universities among executives right below the presidential level, many senior academic leaders bristle at the suggestion that institutions need to build internal pipelines to the presidency. Perhaps it’s because more than half of the presidents in our survey believe that external candidates make better presidents anyway.

“Succession planning is hard to do in higher education,” said Mary Sue Coleman, president of the American Association of Universities and former president at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and the University of Iowa. “We take the attitude that we’re going to do a national search and find the best person.”

The next generation college presidency

Even without the pressures bearing down right now on higher education, many college presidents are likely in the final years of their tenure given the demographics of those in the top job. A wave of departures is expected to come among presidents over the next few years.

Where their successors will come from remains a key question for governing boards and other key stakeholders on campuses. Presidential transitions, especially if they occur frequently, tend to stunt the growth of an institution. Searches typically take six months or longer; once new presidents arrive, they go on “listening tours” for their first year; and then they embark on a lengthy strategic-planning process. By then, 18 to 24 months would have passed since the president started.

Higher education’s talent factories

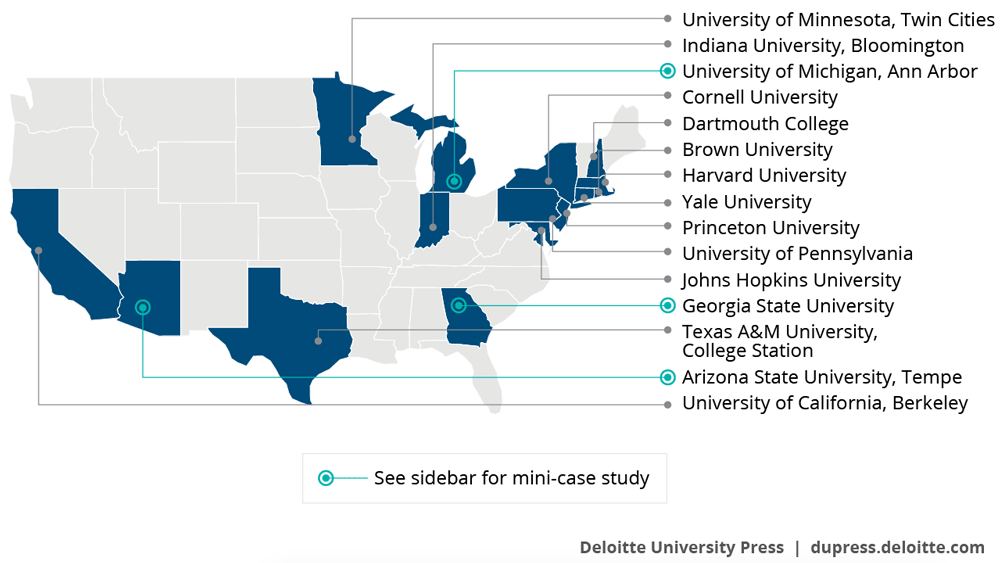

Our study of more than 800 CVs of sitting presidents found that many leaders had institutions in common in their employment history. We analyzed the data in the CVs to identify presidential “talent factories.” These are campuses where a number of presidents have held a position as a faculty member, dean, provost, or senior staff at some point in their careers.

Institutions in the Ivy League dominated the list. The University of Michigan at Ann Arbor was the top public institution on the list, perhaps because of its size. (It has 19 schools and colleges.) Two other public institutions made a surprise appearance on the list: Arizona State University and Georgia State University.

The report includes mini-case studies of three of the talent factories: University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Arizona State, and Georgia State.

In the absence of succession planning in higher education, it’s unlikely that the search process will change much in the years ahead. But based on our research, here are five strategies and approaches that can help improve the pipeline to the presidency and can give the next generation of campus leaders the opportunity for effective tenures:

- Develop intentional training and leadership development opportunities aimed at prospective college presidents. Many leaders in higher education no longer have the time to learn on the job or become adequately trained within the narrow scope of senior-level positions that historically have led to the presidency. Rather, they should consider professional development opportunities that give them the big-picture view of the institution, its various functions and academic disciplines, as well as higher education as an industry. Such programs could evolve at the campus level, like those that have been developed at Georgia State, University of Michigan, and Arizona State (see case studies), or could be national in scope, such as the Aspen Presidential Fellowship for Community College Excellence or the Arizona State-Georgetown University Academy for Innovative Higher Education Leadership.

- Align short-term tactics and long-term strategies. There are few incentives to encourage leaders to experiment with new ideas and models for the future. Too many governing boards and presidents are worried about the near term and thus focus on quick wins that might result in a publicity spike or help in the rankings. Higher education is a long game; the most fundamental role presidents play is unlocking the capacity of the institution to support its mission and the community members engaged in its work. Boards should set clear long-range goals for presidents and evaluate them not only on their annual performance, but also how well they are progressing toward the more distant horizon.

- Gain a better understanding of the role of presidents among search committees and set up a transition team to onboard the president. The group responsible for hiring presidents often lacks deep understanding of the job. The panels should include sitting presidents or former chief executives who can provide the best perspective to the search committee members on the skills and competencies needed in the role. Search committees should also avoid ending their work once the president is hired. Presidents need assistance in the transition to the role, and search committees should be reconstituted into a transition committee or a transition coach should be hired to help the new president build momentum for the first few months in office.

- Develop a willingness to look beyond traditional backgrounds. Search committees pay lip service to nontraditional candidates, but rarely take the risk of actually hiring them. What’s more, academic leaders typically bristle at the prospect of a new president who comes from a nontraditional background. Given the diverse set of skills needed to run institutions these days and with provosts increasingly saying they don’t want to be presidents, search committees may have little choice but to consider candidates from nontraditional backgrounds. But not hailing from academe doesn’t mean candidates are intellectual lightweights or can’t adjust to the norms of the academy. After all, intellectuals don’t end up just in academia. Being transparent and following a well-publicized process in the search to gain buy-in from stakeholders can be critical to gaining acceptance of these new leaders.

- Build relationships with various stakeholders both on- and off-campus. Presidents are hired by a board and report to a board, but when on campus, most of the interaction presidents have is with faculty and students. The latter group, in particular, is gaining influence on campuses, and presidents would be wise to pay attention to the rising activism among their ranks. The presidency has largely become an external job, and as a result, presidents spend their time increasingly off campus. College leaders should spend more time on campus engaging with faculty members and students and weaving themselves into the fabric of the institution they represent on a daily basis.

Talent factory: University of Michigan at Ann Arbor

A key line in Michigan’s famous fight song, “Hail to the Victors,” is “the leaders and best.” The university has long thought of itself as rising to challenges, “willing to be out there when others aren’t,” said Mary Sue Coleman, Michigan’s president from 2002 to 2014. During Coleman’s tenure, the university defended the use of affirmative action in its admissions policies before the US Supreme Court and entered into a groundbreaking partnership with Google to digitize the print collection of the university library.

The “unique combination” of tackling grand challenges and the decentralized nature of Michigan, with 19 schools, some the size of entire institutions, tends to develop leaders for other colleges and universities, Coleman said. “Our deans had to be entrepreneurs and raise money,” she said.

Although Michigan is among the top universities when it comes to its administrators going elsewhere to become college presidents, Coleman said the university was never intentional about training its leaders. Michigan does have informal leadership programs for department chairs and deans, where they learn about the particulars of university finances and fundraising, among other subjects.

Coleman said those meetings were useful for administrators, but she is skeptical about building more deliberate pathways to the presidency. “I think people need to demonstrate their leadership,” she said. “It’s up to the president and provost to look deep in organizations for people showing leadership ability and give them the opportunities to shine.”

Talent factory: Georgia State University

In recent years, Georgia State University has received plenty of attention for how its innovations around student advising and financial aid have produced big gains in the university’s retention and graduation rates. Georgia State was named one of the most innovative universities by US News & World Report.13 Its president, Mark Becker, was singled out as one of the 10 most innovative college presidents by Washington Monthly.14 And it’s a founding member of the University Innovation Alliance.

Such accolades have drawn the attention of other institutions looking for leaders. “They’re attracted to candidates from here because of our accomplishments,” Becker said. “The publicity has also improved the pools of candidates for administrative positions at Georgia State.”

The university also follows a more deliberate path to preparing future leaders. Each month during the academic year, the university hosts a series of gatherings for department chairs and deans about university operations—everything from budgeting to leadership. “We realized we didn’t have a lot of bench strength and the only way we’d get it is to develop it,” Becker said.

Becker said higher education has a sufficient amount of talent waiting in the wings to fill its leadership void. More faculty members should be encouraged to take on administrative roles, he said, since their pathways tend to be flat unless they assume different tasks. “A lot of people have success in academe but they get bored and stuck in a rut,” Becker said. “They have the skills to succeed in administration and there’s a broader set of careers out there for them.”

There is no doubt the life of the college president and the pathway to the top job have evolved greatly over the last century. Further changes can be expected, if not predicted.

“There is no prototype of a president going forward,” a president of a public land-grant university told us. “Presidents need the skill sets of a politician, an academic, and an entrepreneur. This used to be a reflective life, but now you have to drive so many airplanes, and all at once.”

Talent factory: Arizona State University

As president of Arizona State University since 2002, Michael Crow is one of the longest-serving college presidents in the United States. In that time, he has turned ASU from a middle-of-the-road state institution into a model of public higher education in the 21st century.

But any university is about more than just one person, and a few years ago many leaders and faculty members at ASU began to wonder about what’s next after Crow. “We realized that we needed to embed the mission and the culture throughout the university and have leadership abilities infused throughout the faculty and staff,” said May Busch, an executive in residence in the president’s office.

In that role, Busch, a former Morgan Stanley executive, created a leadership academy for three dozen faculty and staff members who attend three two-day offsite sessions during the academic year. Part of the goal of the program, now in its fifth cohort, is to build better connections between schools, departments, and disciplines across a vast enterprise. “The future is about interdisciplinary thinking and research and people need to be better equipped to think like that,” Busch said.

But Busch said the program is more than just an attempt at succession planning. “Succession planning is just a bunch of names in a drawer,” she said. “We’re trying to develop who can think for themselves and have the behaviors of entrepreneurs.”

The university is now extending the reach of the program, piloting an academy for senior administrators. (The university also runs the Academy for Innovative Higher Education Leadership, a national leadership development program, in partnership with Georgetown University.)