Radio: Revenue, reach, and resilience TMT Predictions 2019

11 minute read

11 December 2018

Do people really still listen to radio? They sure do—even young people—and advertisers would do well to take notice of them.

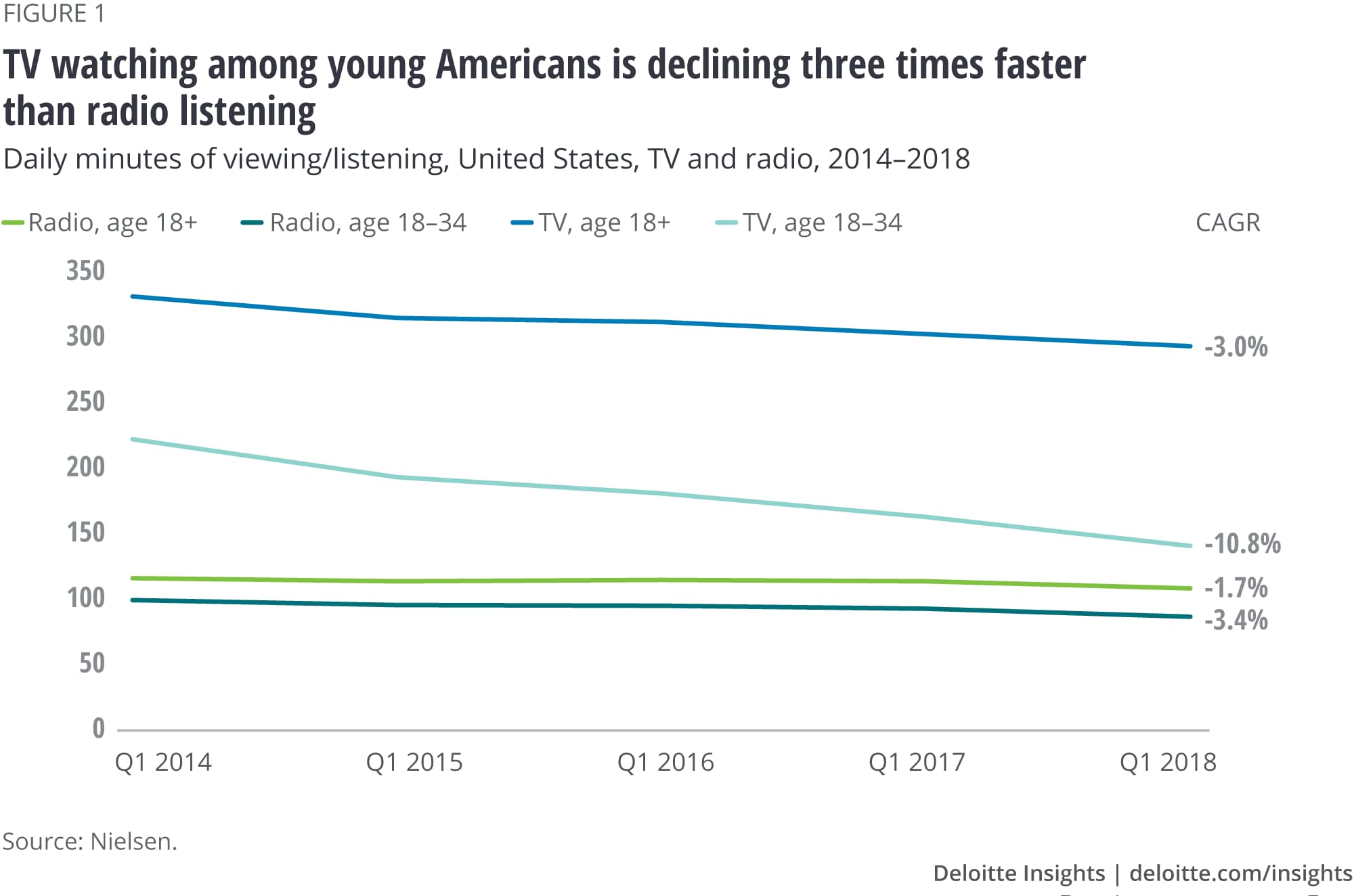

Deloitte Global predicts that global radio revenue1 will reach US$40 billion in 2019, a 1 percent increase over 2018. Further, Deloitte Global predicts that radio’s weekly reach will remain nearly ubiquitous, with over 85 percent of the adult population listening to radio at least weekly in the developed world (the same proportion as in 2018), and reach will vary in the developing world. Combined, nearly 3 billion people worldwide will listen to radio weekly.2 Deloitte Global predicts that adults globally will listen to an average of 90 minutes of radio a day, about the same amount as in the prior year. Finally, Deloitte Global predicts that, unlike some other forms of traditional media, radio will continue to perform relatively well with younger demographics. In the United States, for example, we expect that more than 90 percent of 18–34-year-olds will listen to radio at least weekly in 2019, and they will listen to radio for an average of more than 80 minutes a day. In contrast, TV viewing among 18–34-year-olds in the United States is falling at three times the rate of radio listening (figure 1). At current rates of decline, in fact, American 18–34-year-olds will likely spend more time listening to radio than watching traditional TV by 2025!

Many readers may scoff at these robust predictions for radio. “That can’t be right … nobody listens to radio anymore.” But radio has commonly been underestimated. Radio is the voice whispering in our ear, in the background of dinner, in an office, or while driving the car. It is not pushy or prominent … but it is there.

How do we know this? Radio listening measurement technology varies by country, but in many markets, the data is collected using passive technology devices worn by consumers that pick up radio programs via an undetectable (to humans) embedded audio signal. When asked to self-report their radio listening habits, humans tend to underestimate it, believing we listen to less than we actually do (see sidebar, “Radio is underreported, but resilient”).3 But the measured reality is that radio is still alive and well.

Radio is underreported, but resilient

In the United States, AM/FM radio listening activity is measured by Nielsen. In 48 major markets, the measurement is done passively through a wearable device called a Personal People Meter (PPM). In smaller markets, a diary system is used. Each year, about 400,000 Americans participate in the measurement program.

The PPM device picks up an inaudible audio signal embedded in AM/FM radio programs. This form of measurement is the gold standard, and it is used as the currency for radio ads and ratings. While not perfect, it is considered highly accurate. According to Nielsen data, more than 95 percent of adult Americans heard an AM/FM radio program at least once in June 2017.

However, human beings are less accurate at measuring and recalling their radio habits. In the back seat of a car pool, in a restaurant, or even in our own homes, radio is unobtrusive but often present, and we consistently report listening to radio less—much less—than passive technological measurement systems say we do (figure 2).

To highlight the tendency to underreport radio listening, consider an August 2018 Deloitte survey that asked people of various ages if they ever listened to radio (any AM/FM radio broadcast, online versions of broadcasts, or satellite radio). When compared to Nielsen data for roughly the same time period, people in every age group underreported radio reach by between 25 and 43 percentage points, with younger listeners underreporting more than older listeners.

There are likely various reasons why radio listening is so consistently underreported in surveys. It is less obtrusive than TV and less novel than watching video on a smartphone. It is often perceived as “merely” background to a lunch or a commuter’s drive. But the radio is on, the sound is coming out of the speakers, and our ears are hearing the radio (and the commercials) even if we are not consciously reminding ourselves, “Hey, we’re listening to the radio.”

Radio’s weekly reach—the percentage of people who listen to radio at least once—has been remarkably stable in the United States. Not only has reach hovered around 94 percent for the last few years, but that number is essentially unchanged from the 94.9 percent figure in spring 2001 (when Apple introduced the iPod).4 Canadian radio reach is only a little lower, at 86 percent.5 Further, an August 2018 Deloitte Global survey found that, of those who report listening to live radio, over 70 percent say they listen either every day or on most days. This finding was consistent for both the United States and Canada, and across all age groups: A majority of radio listeners are tuning in as part of their daily lives.

Learn more

Listen to the related podcast

Watch the video and view the infographic for this prediction

View TMT Predictions 2019, download the full report, or create a custom PDF

It is true that Canadian radio revenue (among both private and public broadcasters, including satellite radio) has been declining, but only very gradually. From 2012 to 2016, total Canadian radio revenue declined 1 percent to C$2.2 billion (US$1.1 billion).6 However, if we exclude public sector radio (whose revenue has been cut back), the decline in private radio revenue only averaged 1.1 percent per year,7 while satellite radio has actually been growing at about 6 percent per year.8

Neither is the resilience of radio purely a North American phenomenon. In Q1 2018, for example, not only was radio ad spending in the United Kingdom up 12.5 percent year over year (after a lengthy period of decline), but radio advertising was the fastest-growing type of advertising, outpacing even internet advertising.9

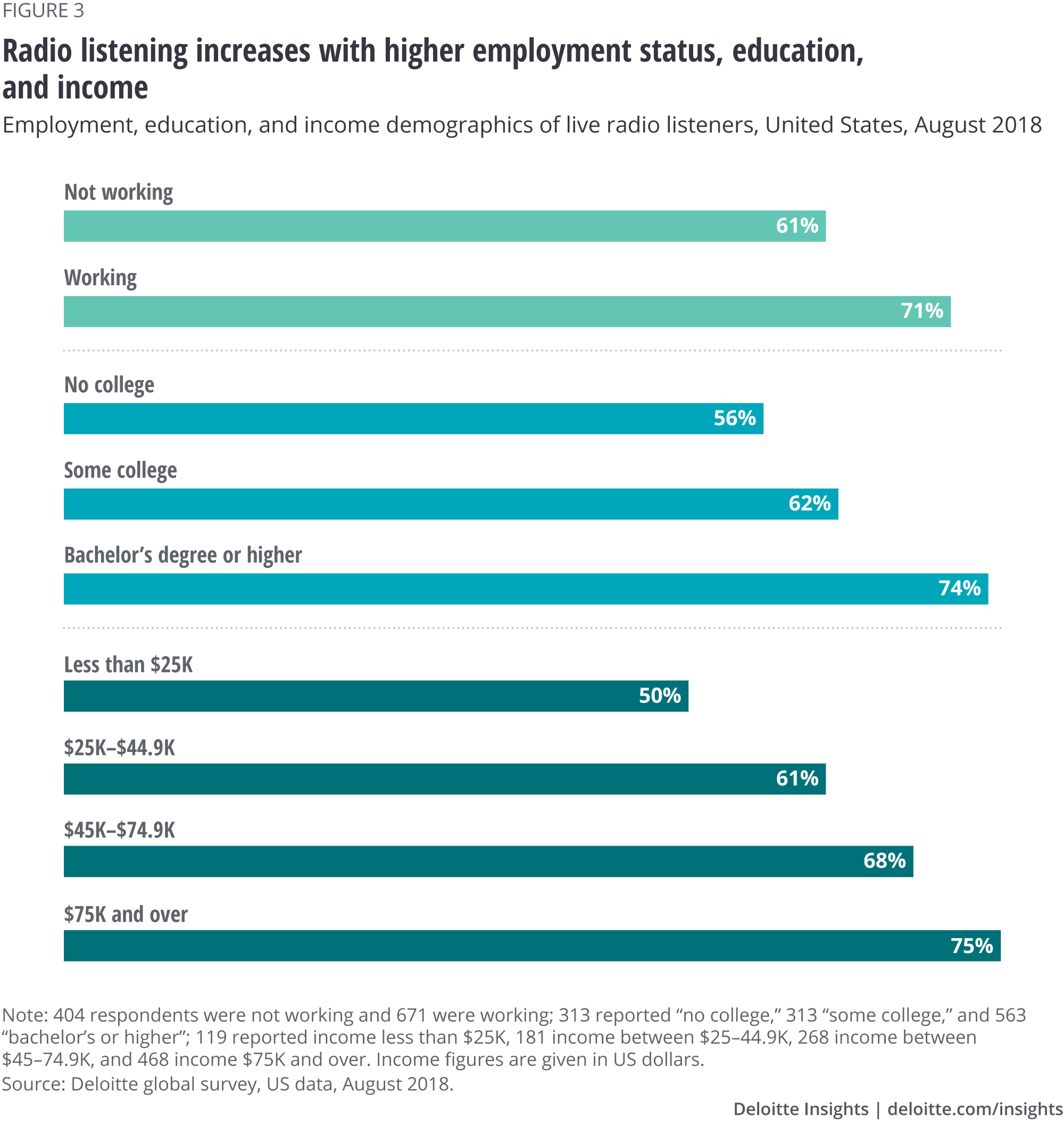

A major reason that advertisers still like radio is its demographics. One might think, since radio in North America is popularly perceived to be largely free and ad-supported, that it would appeal mainly to demographics that are of less interest to those who buy advertising. The exact opposite is true: The August 2018 Deloitte Global survey found that the percentage of Americans who report listening to live radio is higher for those who are working, those with more education, and those with higher incomes (figure 3). Keep in mind, too, that, because radio listening in this survey was self-reported, the real numbers are likely 25 percentage points higher for older demographics and 40 percentage points higher for younger age groups.

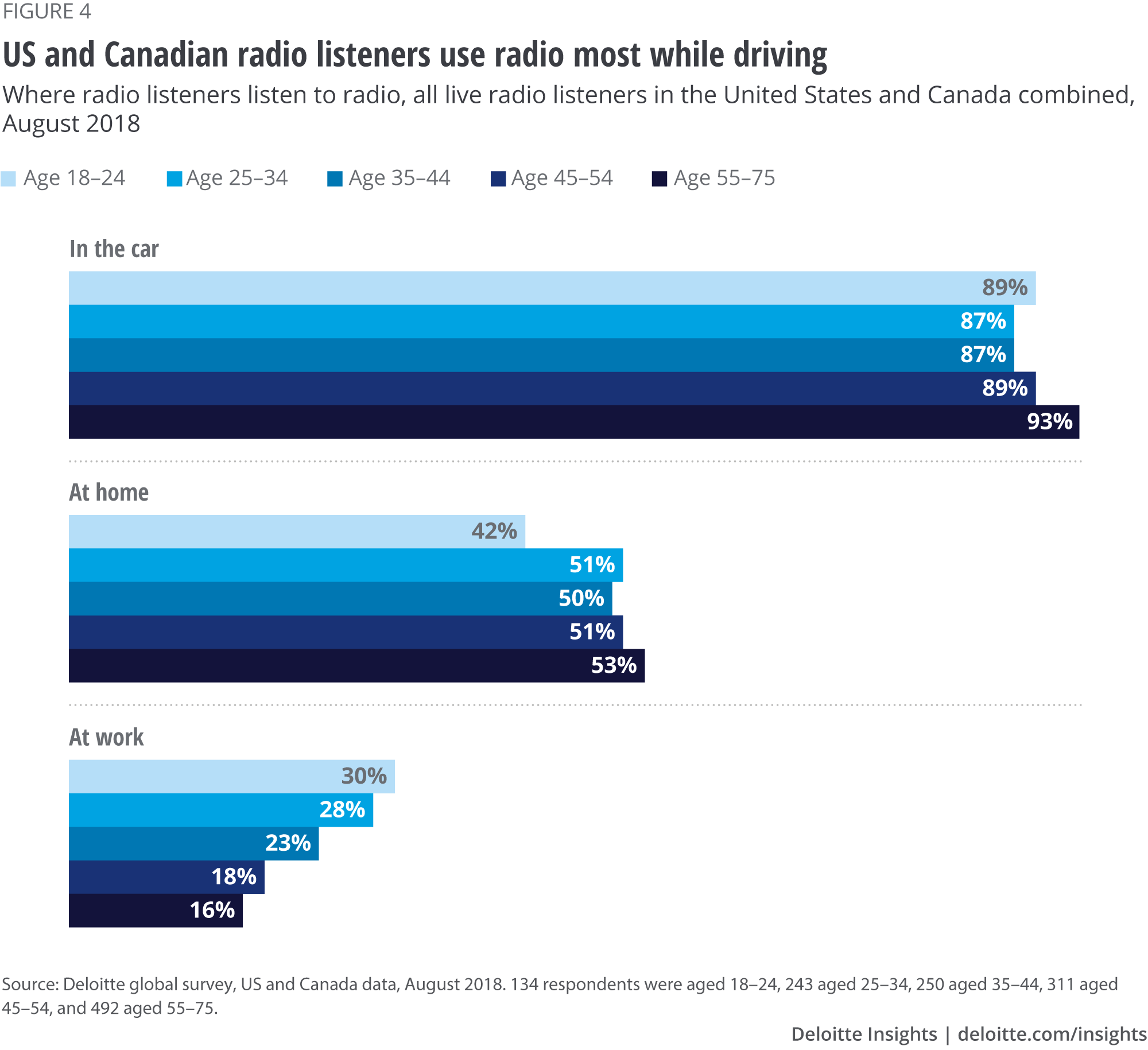

When considering radio’s attractiveness to advertisers, it is important to note that radio’s popularity varies significantly from country to country in both reach and revenue generated per capita, with the United States and Canada at the extreme high end for the latter.10 Likely due to these countries’ commuter car culture and the dominance of radio being listened to in cars (figure 4), radio listeners in the United States are “worth” US$67 per year in radio revenue per capita for the industry as a whole. In contrast, the radio industry in Canada and Germany makes about US$20 less per listener per year. In Sweden and Australia, the radio industry makes just under US$40 per capita per year; in the United Kingdom and France, around US$25 per capita per year, and in most other countries for which data exists, less than US$10 per capita per year (figure 5). Interestingly, there seems to be no clear correlation between radio reach in each country and industry revenues.

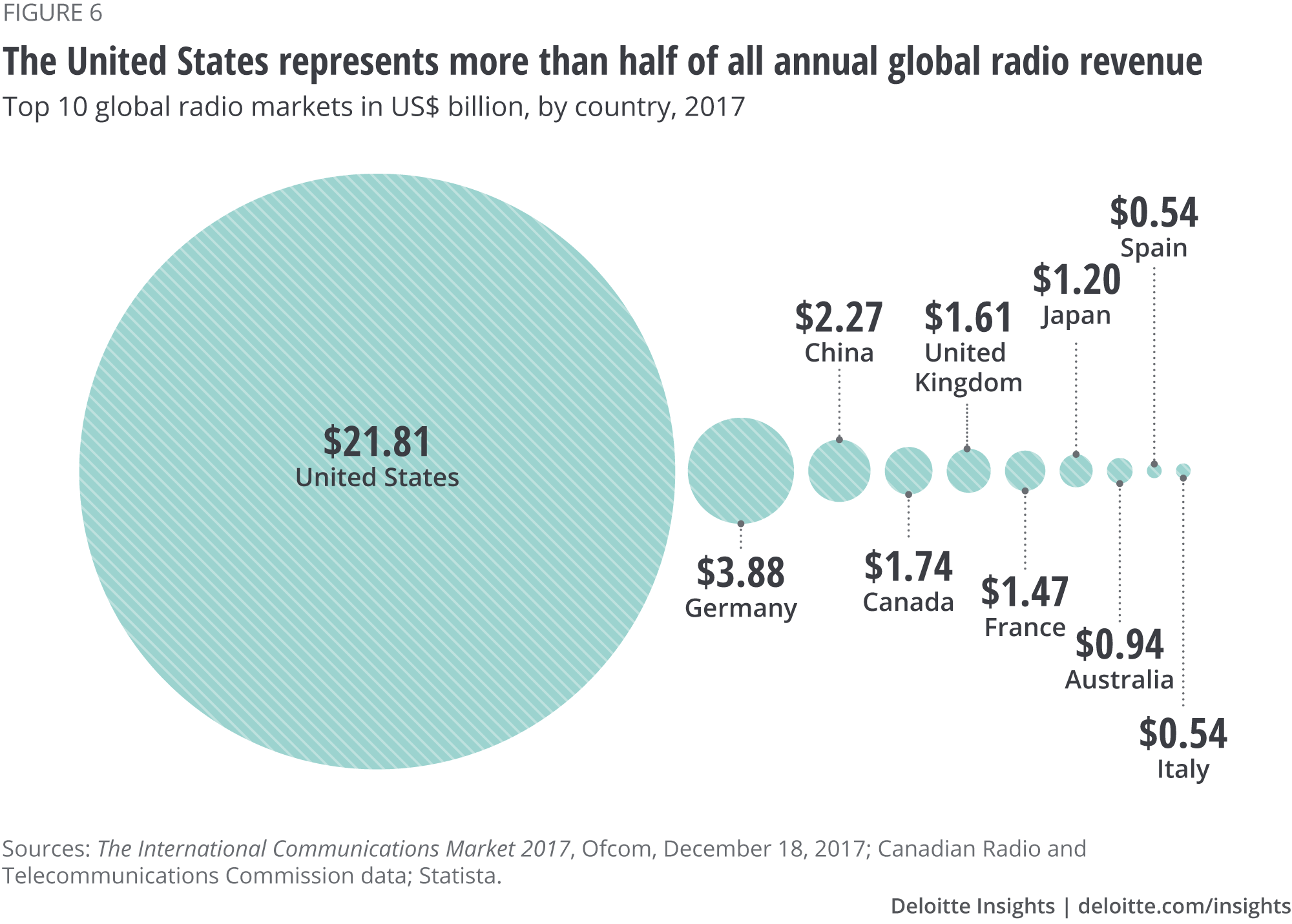

When one talks about the “global radio industry,” the size of the US market—driven by its large population, radio’s high reach into this population, and the very high value per capita of US radio listeners—makes it represent over half of all global radio revenues in 2017 (figure 6). From the same figure, even excluding the United States, radio’s global market is worth nearly US$20 billion per year, and so remains important. It is also critical for both the radio and advertising industries to understand just how country-specific the radio market is. What is true in North America may not be true in Europe, Africa, or Asia—and what holds in one country may not hold in the next. Radio per capita revenue in Germany, for instance, is three times higher than next door in the Netherlands to the west, and 13 times higher than in Poland to the east.11

Bottom line

The obvious implication of all of the aforementioned aspects is that radio is not going away, and it should be a big part of the ad mix for those buying advertising. However, the importance of radio in advertising may not be well known: A 2018 UK study found that, even though radio had the second-best ROI for brand building, advertisers and agencies ranked it sixth out of seven.12 If these results reflect typical attitudes, radio appears to be the most undervalued ad medium for brand-building. But if advertisers come to appreciate radio’s value, the share of ad dollars that radio receives is likely to be stable at worst, and may even rise—as it did in the United Kingdom in Q1 2018.

At least some of what will be required to help radio attract more advertising revenue is better dissemination of the reality behind radio’s resilience. Most people in the media industry hold negative assumptions about radio’s effectiveness, largely due to entrenched myths that denigrate radio’s reach and daily listening minutes, its popularity with young audiences, and its demographics with regard to income and education. The industry itself is partially to blame for these misunderstandings, and an aggressive campaign of mythbusting—always backed up by hard evidence—will likely need to be a key strategy for broadcasters and their industry associations worldwide.

One widespread belief about radio is both truth and myth at the same time. It is widely assumed that the most common venue where North Americans dial in is in their cars. This is true: Around 90 percent of radio listeners in the United States and Canada, across all age groups, do listen while in the car (figure 4). But the flip side of that belief—that North Americans listen to radio only in their cars—needs some mythbusting. While not as prevalent, people in North America definitely are listening to radio in places other than cars. As we saw in figure 4 earlier, about half of North Americans aged 25–75 listen to radio while at home (although only 42 percent of 18–24-year-olds do so). A nontrivial proportion are also listening at work, with the percentage being highest for 18–24-year-olds at 30 percent, declining to half that for those aged 55–75 years.

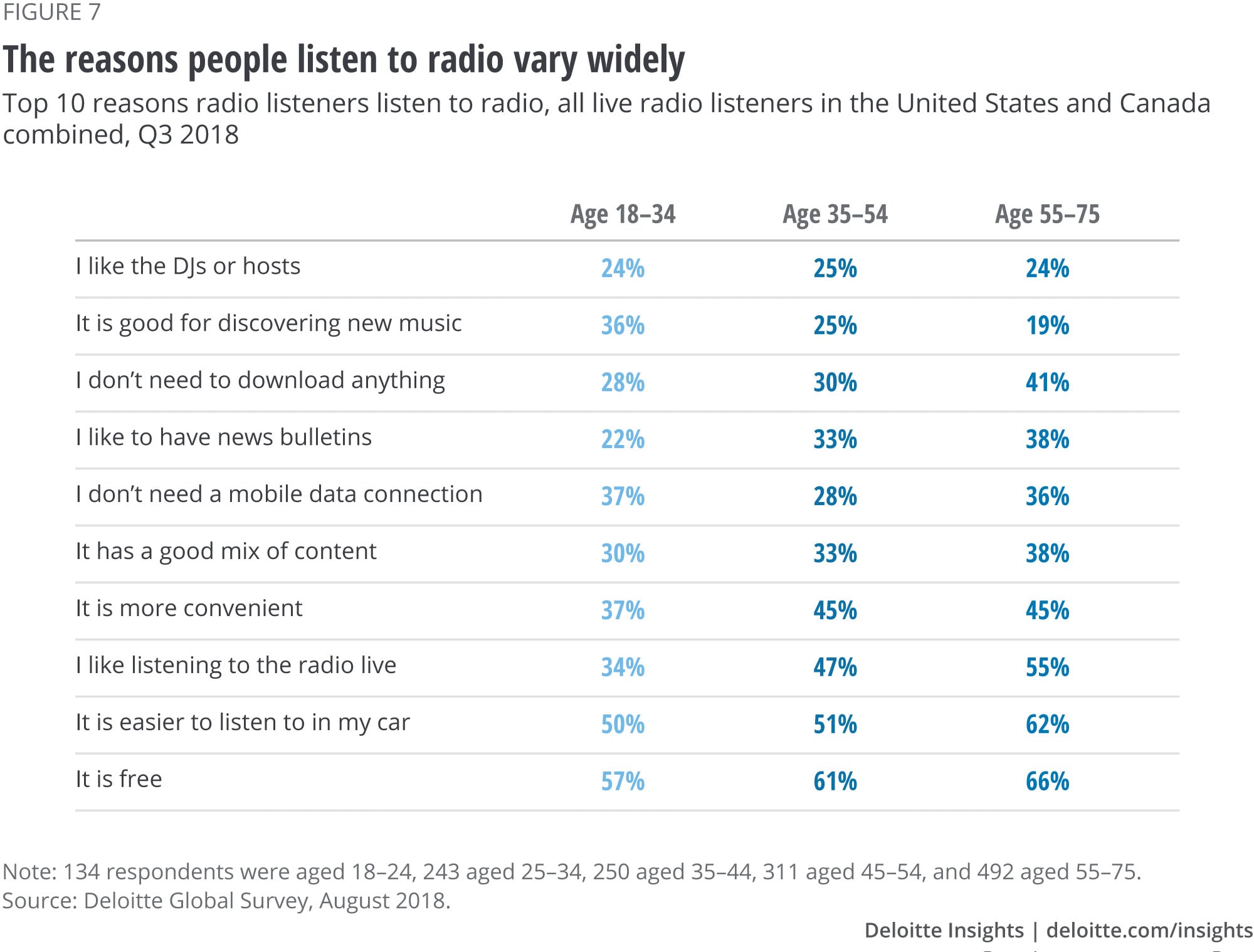

Perhaps our most challenging finding is that there is no single, powerful, universal reason that people who listen to radio decide to listen (figure 7). Should a radio broadcaster spend a lot of money on attracting top DJs or hosts for the morning drive?13 That will certainly attract or retain some listeners, but only about 25 percent across the various demographics. Playing new music so that listeners can discover new acts works well for the 18–34-year-old audience, with 36 percent saying that this is one of the reasons they listen to radio at all—but only half that proportion of 55–75-year-olds listen to radio for discovery. For some demographics, the facts that radio is live, free, and easy to listen to in the car were the only reasons that more than half of radio listeners gave for listening.

Our last takeaway is almost paradoxical. In the realm of traditional media, print newspapers are locked in an ongoing struggle for profits—and, in some cases, even their very existence. And although TV ad revenues continue to grow, at least a little, the decline in TV watching by young people—in multiple countries, TV watching by the youngest demographic has gone down by about 50 percent in the last six to seven years—suggests that TV almost certainly faces challenges ahead.14 Radio has no such existential crisis or looming demographic cliff. In 2017, radio attracted about 6 percent of global ad spending (about 9 percent in North America), and in 2019, it will likely be around 6 percent again.15 These advertisers know that advertising on radio works, and it needs to be part of any ad campaign.

Many things have changed since the year 1962, in which the hit movie American Graffiti was set. But driving around in a car and listening to music, news, and a loudmouth DJ is still very much part of the US cultural fabric in 2019. In a world where digital changes everything, radio may be the exception.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

Artificial intelligence: From expert-only to everywhere Article6 years ago

-

Quantum computers: The next supercomputers, but not the next laptops Article6 years ago

-

Does TV sports have a future? Bet on it Article6 years ago

-

3D printing growth accelerates again Article6 years ago

-

Radio: Revenue, reach, and resilience Article6 years ago