Redesigning work in an era of cognitive technologies has been saved

Redesigning work in an era of cognitive technologies Deloitte Review Issue 17

27 July 2015

Cognitive technologies, a product of the field of artificial intelligence, can and will be used to eliminate jobs. But leaders face choices about how to apply cognitive technologies. These decisions will determine whether workers are marginalized or empowered, and whether their organizations are creating value or merely cutting costs.

Rapid progress in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) has provoked intensive debate about the implications of this trend for society. Some see a driver of economic growth and boundless opportunities to improve living standards. Others see existential threats ranging from killer robots to widespread technological unemployment. Though we believe the worst of the fears are overblown, cognitive technologies—the products of the field of AI—cannot be ignored. They are an emerging source of competitive advantage for businesses and are on their way to ubiquity at work and at home.

Artificial intelligence researchers have sought to develop techniques to enable computers to perform a wide range of tasks once thought to be solely the domain of humans, including playing games, recognizing faces and speech, making decisions under uncertainty, learning, and translating between languages. We distinguish between the field of artificial intelligence and the technologies that emanate from the field, which we call cognitive technologies. Commonly used cognitive technologies include machine learning, computer vision, speech recognition, natural language processing, and robotics.1

Listen to the related podcast, “Redesigning work in an era of cognitive technologies”

Over the next three to five years cognitive technologies likely will have a profound impact on work, workers, and organizations. These technologies can and will be used to eliminate jobs. But they will also make it possible to redesign work, creating new opportunities for workers and greater value for businesses and their customers. Business leaders should understand the four main automation choices and the cost and value strategies we describe. And they should tune their talent practices to attract and develop the skills, including creativity and emotional intelligence, which will become relatively more important in an era of cognitive technologies.

Conflicting views

There is an active, often sensationalist, debate underway over the impact of cognitive technologies on employment. One side forecasts massive unemployment as these technologies take on work formerly done by people. The other predicts a new incarnation of a familiar historical pattern of technological change: New technologies increase productivity, which increases wealth, drives economic growth, and creates demand for workers with new skills.

A widely cited recent analysis by researchers at the University of Oxford is an example of the dark side of the debate. The study estimated that 47 percent of total US employment is “at risk” from computerization over the next decade or two.2Gartner Group, an information technology research firm, takes a similar position, forecasting that “one in three jobs will be taken by software or robots by 2025.”3 Three Gartner analysts have offered a starker “strategic planning assumption:” “By 2030, 90 percent of jobs as we know them today will be replaced by smart machines.”4

Not everyone believes organizations should begin preparing for a future without jobs and workers. David Autor, a prominent economist and authority on the interplay of technology and employment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, believes the degree to which machines will substitute for human labor is often overstated. “The challenges to substituting machines for workers in tasks requiring adaptability, common sense, and creativity remain immense,” he writes. He argues that strong complementarities between machines and human labor, which “increase productivity, raise earnings, and augment demand for skilled labor,” are not receiving enough attention.5 Rodney Brooks, a robotics expert and founder of two prominent robotics companies, believes that technologies like robotics are more properly seen as “getting rid of a really dull job that we shouldn’t be torturing people with” rather than putting people out of work.6

We favor the more positive view of the future. While good progress is being made in applying cognitive technologies to narrow domains, automating entire processes or jobs is rare and unlikely to become common in the near term. More likely, especially in the next three to five years, parts of jobs will be automated by cognitive technologies. Workers—including knowledge workers—will be interacting with automated smart machines, as airline pilots and workers in advanced factories do today. For this reason, it is crucial for business leaders to take a closer look at the coming impact of cognitive technologies on work, workers, and organizations.

Cognitive technologies and the automation of work

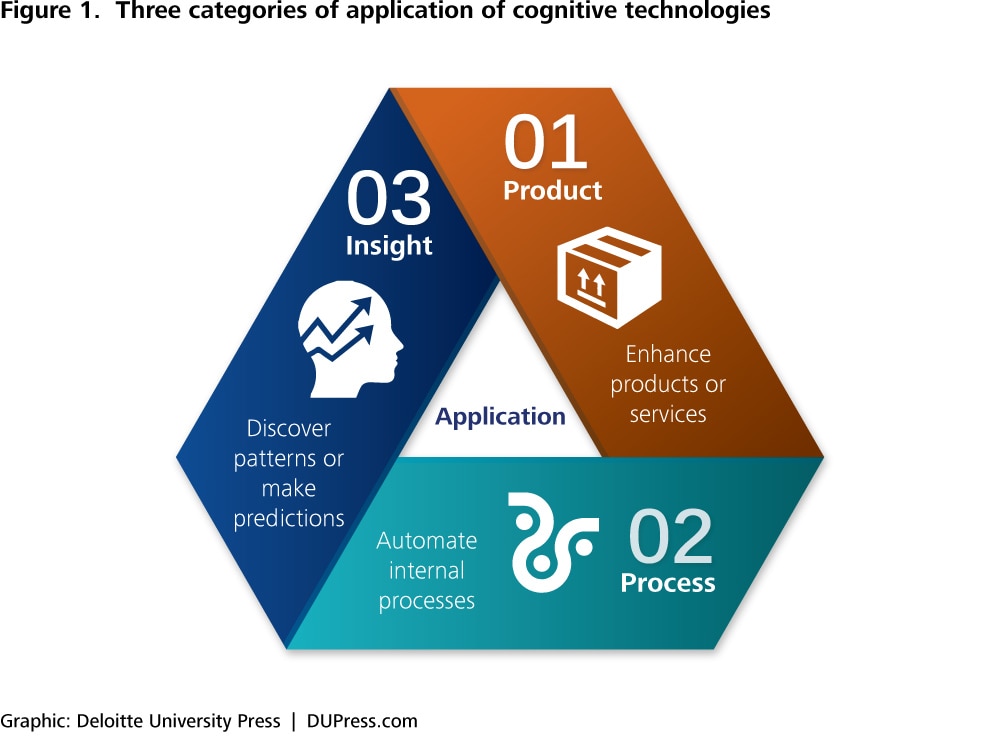

In previous work, one of us (David) along with other colleagues analyzed over 100 applications of cognitive technologies. We found these applications tend to fall into three categories: product, process, and insight (See figure 1).7 Each category of application has distinct impacts on work and workers.

Product applications embed cognitive technologies in products to provide “intelligent” behavior, natural interfaces (such speech and visual), and automation. The impact of product applications on workers ranges from none (robotic toys or intelligent thermostats), to marginal (robotic vacuum cleaners may reduce hours demanded of house cleaners), to significant: Autonomous vehicles are displacing mining truck drivers and train operators,8 and may one day take jobs from taxi drivers or truckers; robots may reduce demand for bricklayers9 and tile setters.10By integrating products that use cognitive technologies into their business processes, organizations are deploying process applications, which we describe next.

Automating an organization’s own work

Process applications use cognitive technologies to enhance, scale, or automate business processes. Examples of this include automating data entry with automatic handwriting recognition, automating planning and scheduling with planning and optimization algorithms, and automating customer service with speech recognition, natural language processing, and question-answering technology. By definition process applications tend to have a direct impact on workers whose jobs were fully or partly automated. As we’ll see below, automation may present challenges to organizations and doesn’t always produce the desired results.

Automating insight

Insight applications use cognitive technologies to reveal patterns, make predictions, and guide more effective actions. Intel, for instance, has employed machine learning to recommend to its sales force which customers to call next and what to offer them.11 Some insight applications can be seen as a form of automation: The decision of what to do next in a given situation, rather than being made by a person, is being made by a machine. Other insight applications enhance, rather than automate existing decision making processes, or perform analyses that were not being done before. Sometimes they join a form of machine learning to other cognitive technologies such as computer vision or natural language processing. For instance, a startup company is combining computer vision and machine learning algorithms to infer the performance of retail stores from satellite images of their parking lots.12

The unintended consequences of automation

The history of automation extends back hundreds of years, and includes manufacturing (industrial automation), aviation, and clerical work (office automation).13 Today, cognitive technologies broaden the reach of automation to new areas, including tasks that traditionally required human perceptual and cognitive abilities. Although automation is undeniably valuable, decades of research have shown that it does not always deliver the benefits it is intended to and can have unintended consequences. As business and technology leaders contemplate using cognitive technologies to automate work, they would do well to learn from the history of automation to avoid repeating its mistakes.

The idea of introducing automation to improve upon the flawed performance of humans may seem compelling. But automated systems can have flaws too. And leaving human operators to handle only the tasks that could not be automated may create its own problems. For instance, tasking humans with monitoring a process that has been automated can cause errors and anomalies to go unnoticed. Studies have shown that it is effectively impossible for even a highly motivated worker to pay attention for more than about half an hour to an information source that hardly changes.14

People tend to lose their skills if they are not practiced regularly. This can lead to the ironic situation in which, precisely when humans need to take command of an automated system, such as an autopilot, they are ill-prepared to do so. Occasionally this has had tragic consequences.15 Even without deskilling, researchers have found, excessive, poorly designed automation can reduce attention and performance on some tasks. Studies have shown that in driving, for instance, too much automation, such as the use of cruise control, can make drivers—especially less-skilled drivers—less vigilant, reducing performance at tasks such as emergency braking.16 Other studies have found that automated systems (like bad bosses) can undermine worker motivation, cause alienation, and reduce satisfaction, productivity, and innovation.17

Technology commentator Nicholas Carr has argued that ill-conceived automation strategies have negative consequences that transcend effectiveness and safety. They can undermine our identities and sense of self-worth.18

Organizations face automation choices

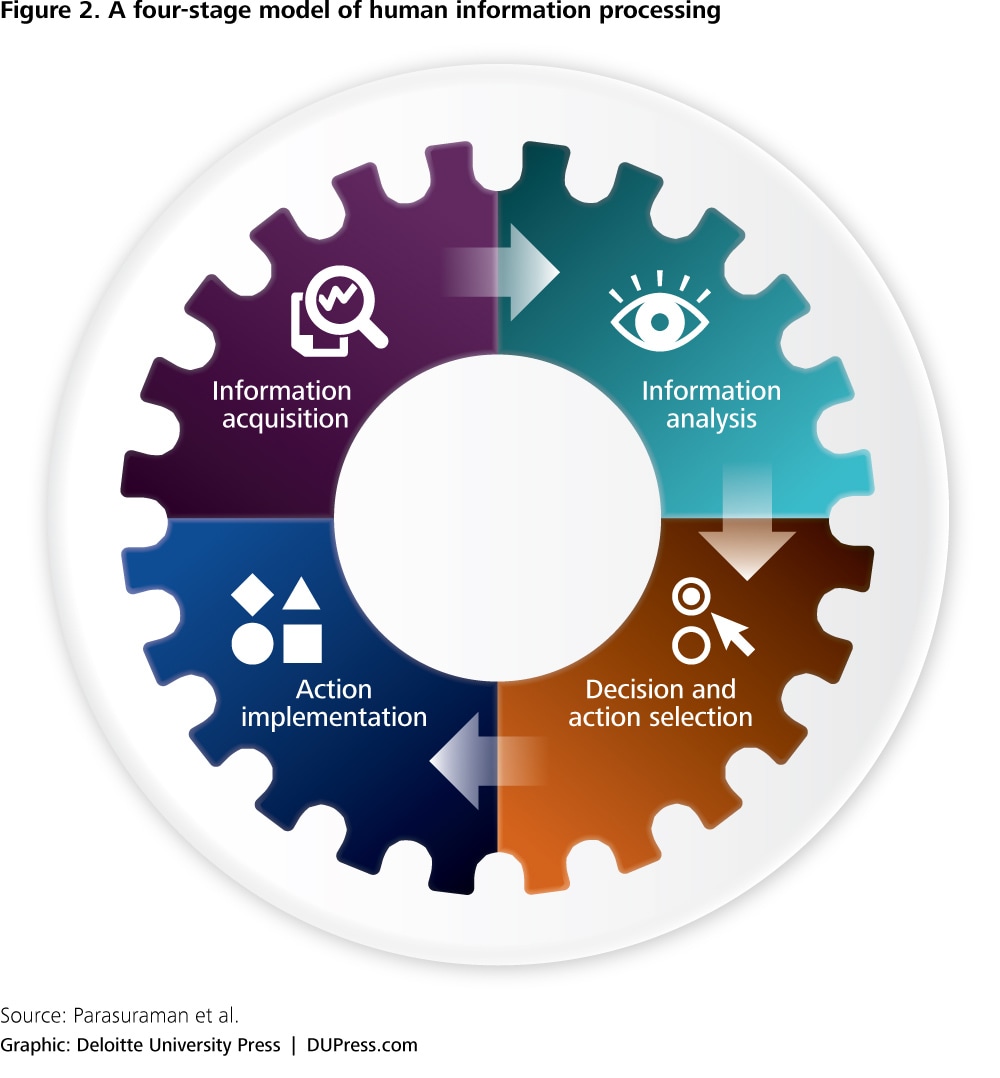

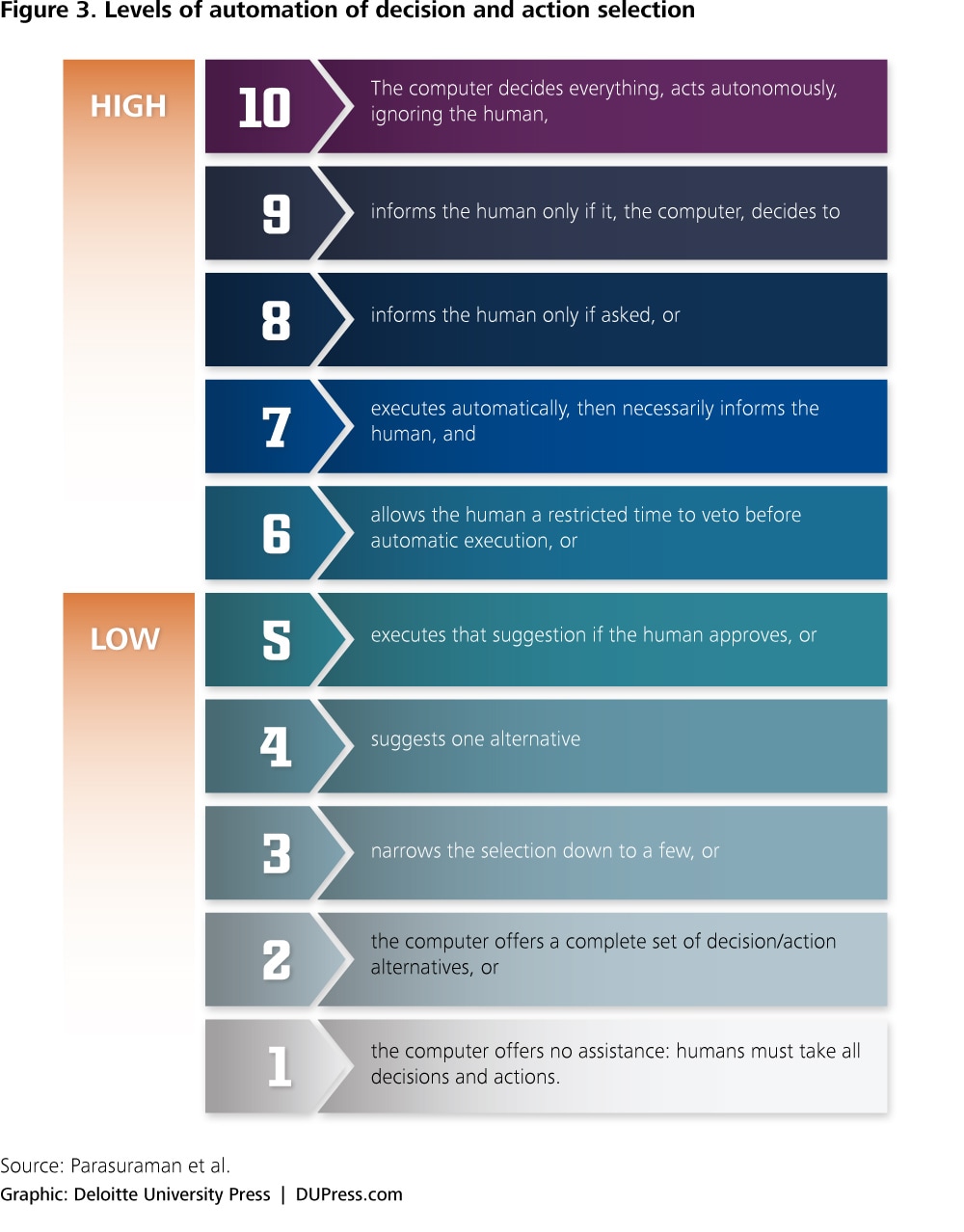

Recognizing the potential problems associated with automation, researchers have looked for objective ways to determine which functions of a system should be automated, and to what degree. To address this need, Parasuraman et al. developed a framework to analyze automation options. It proposed that automation can be applied to four broad classes of functions: 1) information acquisition; 2) information analysis; 3) decision and action selection; and 4) action implementation (see figure 2). Within each of these types, automation can be applied across a continuum of levels from low to high, that is, from fully manual to fully automatic(See figure 3).19

The authors suggest that an automation design should be evaluated first by examining its consequences on human performance and second by considering factors such as automation reliability and the costs associated with the consequences of the actions or decisions. This widely cited work is one of multiple attempts in the field to guide automation design decisions.20

From replace to empower: A talent-technology model

To complement the academic work on automation design, we propose a framework that highlights the perspective of the worker affected by automation and enables us to assess the business implications of various automation choices. This framework may be particularly useful for leaders of organizations considering the impact of cognitive automation on creative or knowledge work.

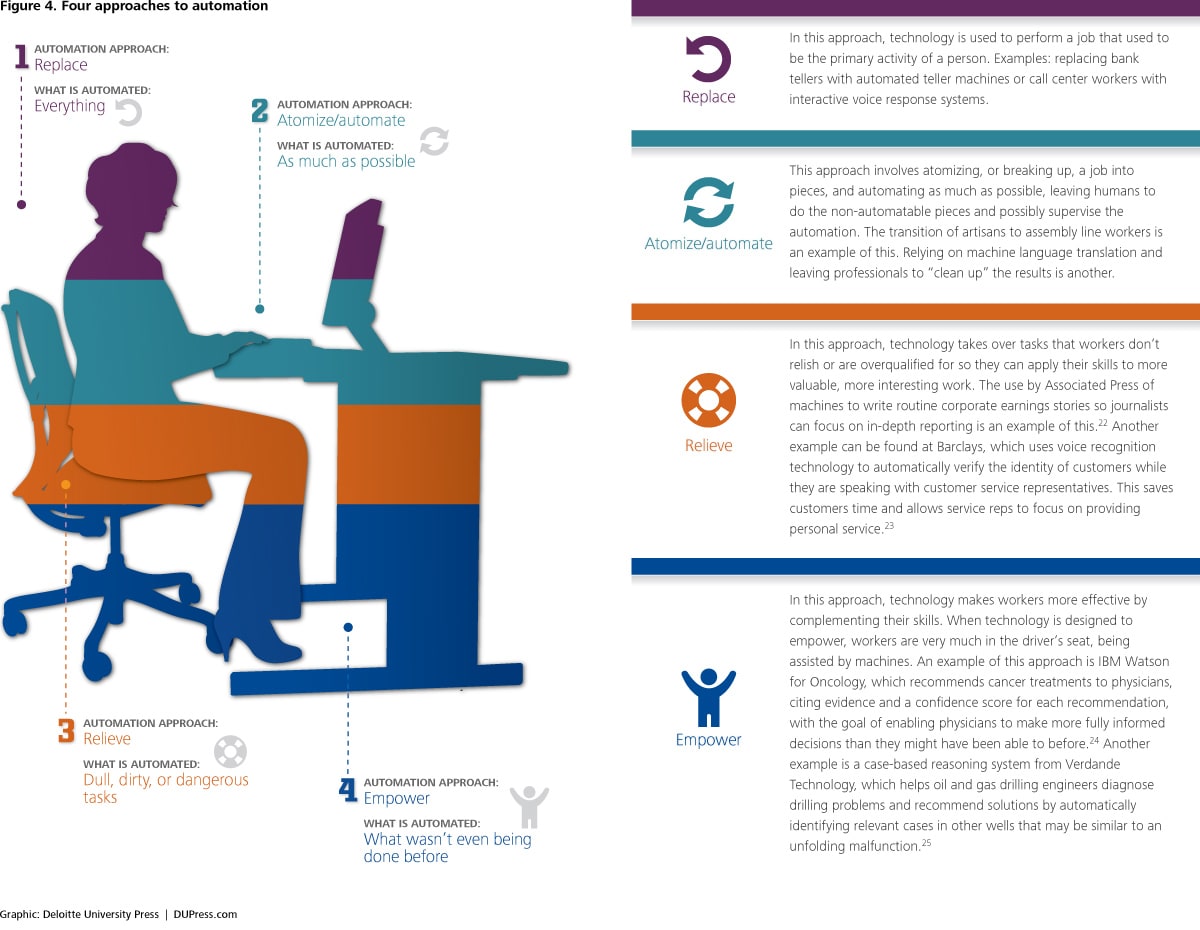

Viewed in terms of its impact on the worker and her relationship to her duties, we identify four main approaches to automation, summarized in figure 4.

Neither the type of job nor the technology used to automate it necessarily determines which automation approach to follow. This is a choice to be made by systems designers and, even more importantly, leaders and strategists. We can illustrate how the four automation choices play out by focusing on one job—translator—and one cognitive technology—machine translation. Each of the four choices entails applying translation technology in different ways, with correspondingly different impacts on human translators.

With the replace approach, the entire job a translator used to do, such as translating technical manuals, is eliminated, along with the translator who did it. In the atomize/automate approach, machine translation is used to perform much of the work—imperfectly, given the current performance of machine translation—after which professional translators edit the automatically translated text, a process called post-editing. Many professional translators consider this “linguistic janitorial work”: It devalues their skills.21 A relieve approach might involve automating lower-value, uninteresting work and reassigning qualified professional translators to more challenging material where quality standards are higher, such as marketing copy. Finally, in the empower approach translators use automated translation tools to accelerate or improve some of their tasks—such as suggesting several options for translating a phrase—but leave the translator free to make choices. This increases productivity and quality while leaving the translator in control of the creative process and responsible for aesthetic judgments.

Maximizing the value of workers and machines

When it comes to the impact on and use of labor, organizations need to do more than sort through the four main automation choices enumerated above. To properly evaluate their options, organizations need to choose between a cost strategy and a value strategy.

- A cost strategy uses technology to reduce costs, especially by reducing labor

- A value strategy aims to increase value by complementing labor with technology or reassigning labor to higher-value work

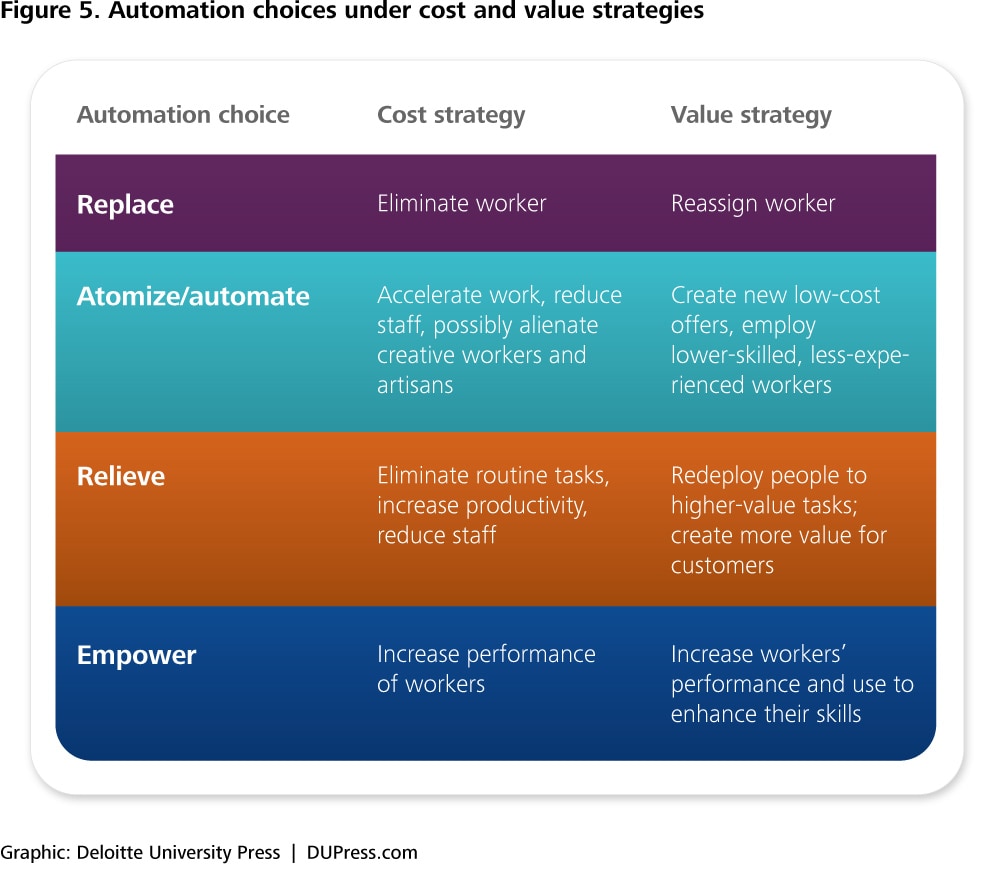

Here’s how each of the four automation choices could play out differently under the two strategies.

Replace. With the cost strategy, organizations replace workers with cognitive computing systems that perform equivalent work. The financial appeal of this choice is clear, but limited to the cost savings that it might achieve. Organizations may produce greater value by reassigning workers to new roles, or expanding their roles. Or they might seek to deploy cognitive systems that not only substitute for human workers but provide superior performance, measured in speed or quality, for instance. These are examples of the value strategy.

Atomize/automate. Atomizing and automating work to reduce labor costs is an example of the cost strategy. As we’ve seen, it can be disempowering and alienating to creative people, the highly skilled, or artisans. A value strategy might use this approach to create new lower-cost offerings that serve the needs of a new market segment. For instance, translation service providers could offer a range of qualities at different prices by varying by the level of automation used in the translation and using less-experienced translators to perform post-editing.

Relieve. A cost strategy might realize the benefits of efficiency with this automation choice by reducing headcount. An example is call centers that automate first-tier customer support in order to reduce staffing levels. A value strategy, on the other hand, might expand or shift the focus of the workers to higher-value tasks. For instance, when a new automated engineering planning system saved the expert-level engineers of the Hong Kong subway system two days of work per week, they reallocated their time to harder problems that require human interaction and negotiation.26

Empower. A cognitive system may empower lower-skilled workers to perform tasks that were formerly performed by higher-skilled workers. This is an example of the cost strategy at work. A value strategy might employ a system not only to empower lower-skilled workers but also to train them and build their skills. It might also be designed to enhance the performance of even highly skilled workers.

It should be noted that cognitive automation, even in systems intended to empower workers, may meet with resistance. An illustration of this can be found at Intel, which, as mentioned earlier, developed a cognitive system to improve sales productivity. The system used machine learning to classify customers and guide sales people on what to offer different customers. Some members of the sales team were initially resistant to following the advice of the machine learning system, possibly because they resented that their salesmanship was being subordinated to a machine. But after an initial group of sales people adopted the system and saw a dramatic improvement in sales productivity, the rest of the sales team was quick to follow.27 If the essence of a sales person’s work is building and maintaining relationships with customers, a little automated assistance that prioritizes customer calls and recommends offers may be an empowering use of technology.

Examples of how the four automation choices could play out differently under the two strategies are summarized in figure 5.

Some skills will become more valuable

As organizations put cognitive technologies to work they have to consider more than what to automate and to what degree and whether to adopt a cost or value strategy. They also must take a fresh look at what skills they are going to need in their workforce. As routine tasks are increasingly subject to automation by cognitive and other technologies, the skills required to perform those tasks will tend to become less valuable. On the other hand, the skills required to perform broadly or loosely defined jobs—skills such as common sense, general intelligence, flexibility, and creativity—and those required for successful interpersonal interactions—such as emotional intelligence and empathy—are likely to become relatively more valuable. This is because, as economist David Autor points out, “tasks that cannot be substituted by computerization are generally complemented by it.” Technology increases productivity, raises earnings, and augments demand for skilled labor. Workers with spreadsheet skills likely receive higher pay than clerks working with pencil and paper before them, for instance. Construction workers skilled with power tools and sophisticated machinery command higher wages than unskilled manual laborers.28

Autor identifies a number of skills that tasks resistant to computerization tend to require. These include problem-solving, intuition, creativity, persuasion—required to perform what he calls “abstract” tasks—and situational adaptability, visual and language recognition, and in-person interactions—required for what he calls “manual tasks.” It is not hard to find examples of tasks like these that have been automated, though. Consider for instance: Google Maps solving navigation problems, Chef Watson devising new recipes,29 suggestive selling on Amazon.com, and robotic store clerks at retailer Lowe’s.30 Automating narrowly defined tasks like these is much easier than automating broadly defined ones. Even if automated navigation and scheduling and configuring are here today, automated general problem solving is not on the horizon. As cognitive technologies automate narrowly defined tasks, the skills and temperament necessary to size up and execute broadly defined tasks—such as critical thinking, general problem solving, tolerance of ambiguity, drive, and resourcefulness—are likely to become more valuable.31

Flexibility, creativity, critical thinking, and emotional intelligence

Designing products, services, entertainment, or built environments that delight people is unlikely to be a job for computers any time soon. The skills these kinds of tasks require, therefore, are likely to become relatively more valuable. There are tools that can make this kind of innovation more reliable, such as best practices, market research, A/B testing, and the like. But the core task of creating something novel, beautiful, or delightful requires not only technical skills specific to a discipline such as product design or film making, but also humanistic skills of empathy and openness to serendipity. Organizations that employ these skills to understand and delight their human customers have always been able to distinguish themselves and will continue to.

Providing the highest-quality customer service experience is also likely to remain a job for people. Even as cognitive technologies make possible increasingly high-quality and personalized automated service, there is currently no substitute for the quality of experience provided by a well-trained and well-equipped human possessed of a high emotional intelligence, energy, and empathy. Businesses that seek to develop and maintain high-value relationships with demanding customers will continue to rely on the human touch in relationship management and service.

Computers remain better at providing answers than at asking questions. But insight starts with posing important new questions. And questioning the actions and decisions of machines is essential to using them to free us, rather than constrain us.

We expect creative skills to become ever more valuable. As noted above, we have seen some demonstrations of computer behavior we would call creative, such as Chef Watson recommending novel combinations of ingredients. But machine-powered creativity requires a human pilot. Even Chef Watson needs human chefs to decide how to prepare ingredients that Watson has selected. Rather than replacing human creativity, cognitive technologies will complement human creativity.32

Critical thinking skills are also likely to become relatively more valuable as cognitive technologies become able to mimic other skills. Computers remain better at providing answers than at asking questions. But insight starts with posing important new questions. And questioning the actions and decisions of machines is essential to using them to free us, rather than constrain us.

Leadership and strategic workforce planning in an era of cognitive technologies

Introducing technology into a workplace always affects workers and organizations. Cognitive technologies, because they extend the power of information technologies to new kinds of tasks, affect work and workers in new ways. This presents challenges that require multidisciplinary solutions. In conversations with dozens of chief human resources officers, we have found that few companies have plans in place to address these challenges.33

Business, talent, and technology leaders should work together to analyze the issues and opportunities presented by cognitive technologies and propose a path forward. An effective approach could include the following elements:

- Forecast. Technology leaders assess the current capabilities of cognitive technologies and develop a view of the trajectory of their performance over the next five to ten years.

- Analyze impact. Business and talent leaders analyze the adoption of cognitive technologies among competitors and leading firms in other sectors and its impact on work design and workforce requirements.

- Develop options. Joint business/technology teams develop options for applying these technologies in current and future business processes to generate business value, including operating and strategic benefits.

- Create scenarios. Based on the applications identified above, talent leaders use the talent-technology model presented here to develop scenarios for redesigning work and restructuring workforces. Scenarios should consider, among other factors, how increasing productivity may reduce the demand for labor in certain functions and how certain skills will become relatively more important while others will become relatively less so.

- Run pilots. Develop and deploy pilots of cognitive applications in one or more processes and talent leaders study the human capital impacts, opportunities, and challenges.

- Develop skills. Talent leaders plan to recruit for and develop the skills likely to become relatively more important, including creativity, flexibility, empathy, and critical thinking.

As cognitive technologies continue to evolve and find new applications, they will often be used in ways that complement work—helping workers be more productive and produce higher-quality results. Leaders should thus look for ways of keeping people “in the loop,” rather than assuming that the best application of cognitive technologies is to eliminate labor entirely.34 They should also identify opportunities where cognitive technologies could help alleviate skills shortages. And they should consider both cost and value strategies, as described earlier.

Strategic workforce planning needs to evolve beyond a focus on talent and people to consider the interplay of talent, technology, and the design of work and organizations. Traditional workforce models assume limits on the kinds of tasks information technology can be used for. Increasingly, those assumptions no longer apply. As cognitive technologies advance in power, organizations are going to need to bring more creativity to workforce planning and the design of work. The greatest challenges may lie in developing a deeper understanding of the integration of cognitive technologies and work.

No one right answer

The adoption of cognitive technologies will change the employment landscape in the coming years. It will inevitably lead to the elimination of some jobs. It will also lead to the redesign of other jobs and the introduction of new kinds of work. Workers whose skills are complemented by cognitive technologies will thrive; those whose skills are being supplanted by smart machines may struggle.

Leaders face choices about how to apply cognitive technologies. These choices will determine whether their workers are marginalized or empowered, and whether their organizations are creating value or merely cutting costs. There is no single right set of choices for organizations to make. As leaders prepare to bring cognitive technologies into their organizations they should consider which set of automation choices will fit best with their talent and competitive strategies.