China Focused fiscal relief to counter coronavirus

If the Chinese government can sustain measures to contain the coronavirus while providing focused fiscal relief to help wavering small and medium enterprises amid the economic standstill, normalcy could slowly resume by Q2.

The coronavirus hit the Chinese economy unexpectedly in January 2020. Within weeks, many countries have drastically reduced or even closed air traffic with China.1

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics Collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

The Chinese government has taken drastic measures, as evidenced by the lockdown of Wuhan—the capital of Central China’s Hubei province, where the outbreak emerged—on January 23 in order to prevent the virus from spreading.

As of February 28, the number of confirmed cases in China had reached 78,961 (following a change in the diagnostic criteria for Hubei on February 13).2 On one hand, the number of new infections outside Hubei (kept below 100 for the seventh consecutive day) is encouraging. On the other, the draconian containment measures imposed by the government make human movement prohibitively difficult, which in turn impedes progress in the resumption of business. According to the latest release by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China, the national average return-to-work ratio of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) hovered around 30 percent by late February.3 Factory production suspension has indeed resulted in supply chain disruptions of some global companies.

The draconian containment measures imposed by the government make human movement prohibitively difficult, which in turn impedes progress in the resumption of business.

However, in the past month, financial markets in China and Hong Kong have shrugged off the jitters caused initially by the outbreak. The Hang Seng Index (one of the proxies for the Chinese economy) tumbled nearly 6 percent in the last week of January, but has since then made up the losses. Meanwhile, the US equity market, which posted impressive gains in 2019 (about 30 percent), had been hitting all-time highs until mid-February, which cannot be solely explained by the Fed’s accommodative monetary stances.4 The widely watched US 10-year Treasury yield fell below 1.4 percent on February 28 from 1.88 percent at the beginning of 2020.5

But despite encouraging news on infection containment in China, the fast spread of COVID-19 in countries such as Italy, Iran, and Korea has raised the risk of a potential pandemic (WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros has warned that coronavirus has "pandemic potential," but isn't there yet).6 As a result, the US equity market has seen corrections of 10 percent within a week due to coronavirus fears. This suggests that investors are bracing for a slowdown in the growth of the global economy in 2020.

A sharp slowdown in Q1

The most important questions around the epidemic revolve around three things: its economic impact on China, its spillover effect on the global economy, and the ramifications of China’s policy responses. If history is any guide, the SARS outbreak, which emerged in Beijing in 2003, is clearly the most relevant benchmark from the perspectives of infection, fatality rates, duration, and economic impact. In the end, 2003 turned out to be a reasonably good year for the Chinese economy, because pent-up demand in H2 powered it ahead once the worst was over.7 Of course, one could also argue that China, along with emerging Asian markets, had then just come out of the Asian financial crisis with low asset valuations, low leverage, and an undervalued RMB—which made reflation much easier. The Chinese economy at that time was due for a recovery, and China’s accession to the WTO (in November 2001) began to yield dividends. Today, the economy is gradually maturing. Even a 6 percent GDP growth requires some fiscal stimulus.

Importantly, the Chinese economy is facing headwinds both structurally and cyclically (see the most recent Voice of Asia).8 According to WHO and various other international organizations, the economic cost of SARS—taking into account its impact on the service sector, the knock-on effect on neighboring economies, investments on hold, etc.—to the global economy was around US$40 billion. The coronavirus will have a much greater impact, given the sheer size of the Chinese economy today, the country’s integral role in the global manufacturing supply chain, and the increasingly important place of Chinese tourists in the world tourism map.

The coronavirus will have a much greater impact than SARS, given the sheer size of the Chinese economy today and the country’s integral role in the global manufacturing supply chain.

In December 2019, our forecast for China’s 2020 GDP growth was 5.8 percent, a shade lower than 6 percent—the implicit official growth target.9 We also assumed that fiscal stimulus would be moderate given corporate debt levels. The coronavirus outbreak has clearly changed the forecast and China’s policy mix. The economy was immediately hit by contracting activity related to the transportation and hospitality sectors.

We think resumption of business could reach 70 percent nationwide by the end of March. The key would be to remove certain bottlenecks on transport and people movements within the next few weeks. SMEs, especially those with thin margins and high fixed costs, could feel a severe pinch. However, if the government can sustain measures aimed at containing the virus—even at the cost of economic activities now—normalcy could slowly resume by Q2.

Based on our observation, the government continues to ratchet up measures to contain the virus. For example, people’s movements are being tracked simultaneously by employers and local communities. If the number of daily new infections outside Hubei continue to fall with minimal cases abroad, calm will slowly return. So far, coronavirus’s fatality rate, at 2.3 percent, is relatively low, and it is much lower among the young, suggesting that older people with preexisting vulnerabilities have been affected worse.10 Assuming containment measures work (there is a decline in the number of people affected), the impact on corporate investment is likely to be insignificant, but consumption and trade will certainly take a hit in Q1. Trade could take a bigger hit if an outbreak emerges in other countries.

However, as they say, desperate times call for desperate measures. We expect policymakers to come up with a slew of policies including fiscal relief and monetary easing throughout H1 of 2020. Again, the comparative advantages of China’s governance model—swift execution of central government policies—will be on full display.

Beijing’s toolkit

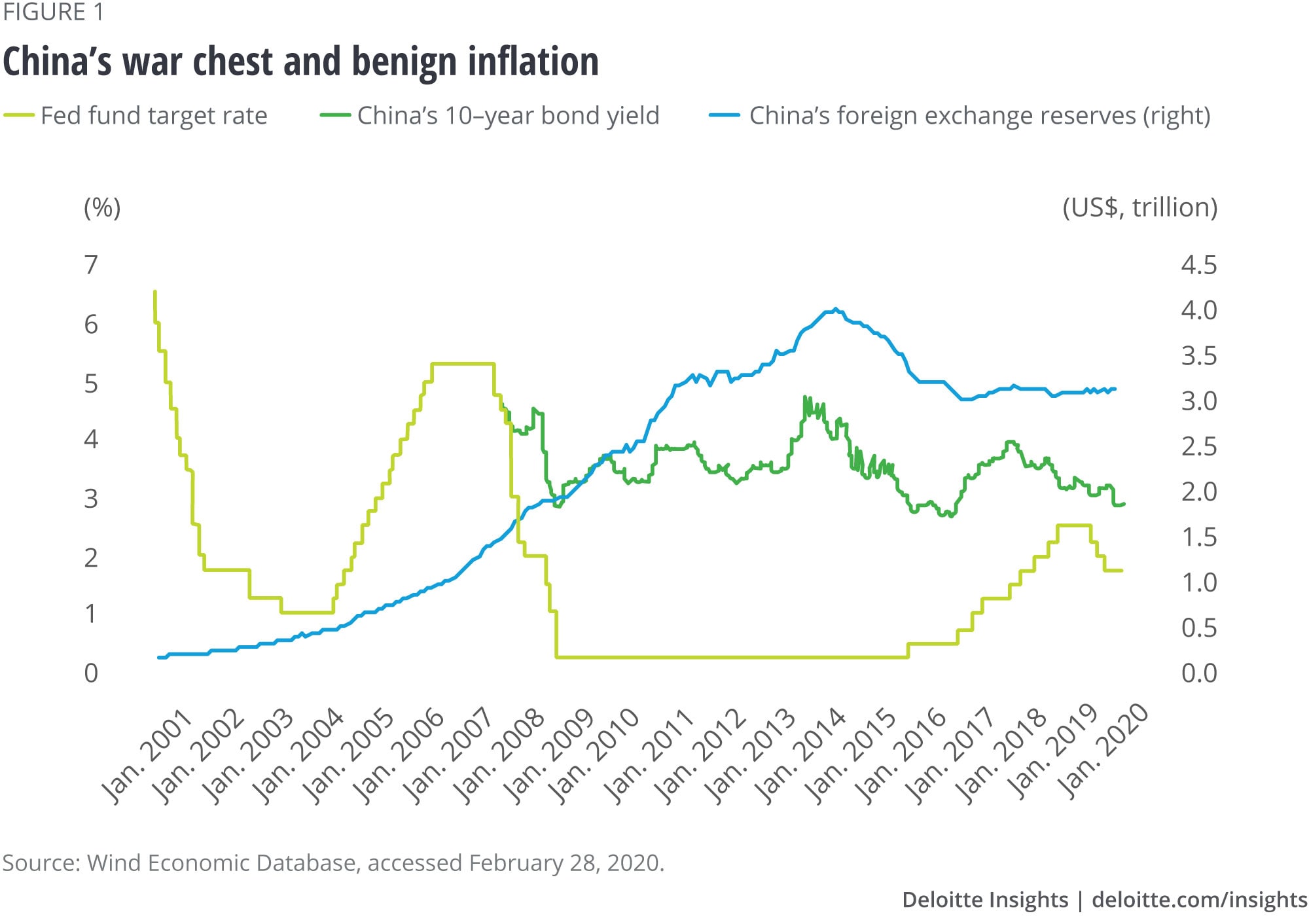

Let’s look at what’s in China’s policy toolbox. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) could easily slash the reserve requirement ratio (RRR) for commercial banks several times this year. The goal would not be to boost banks’ profitability, but rather to act as an incentive for banks to provide credit in a more focused manner to those affected by the epidemic. In other words, the PBOC should do everything it can to alleviate a liquidity crunch. The large US$174 billion injection of liquidity by the PBOC to the economy on February 3 was intended as a signal to commercial banks not to engage in credit grudging should firms face a liquidity crunch.11

The last monetary easing in November 2019 was merely 5 basis points, suggesting that the PBOC purposefully saved ammunition for “desperate times.”12 The current epidemic clearly warrants all sorts of countercyclical measures including making the RMB exchange rate more flexible. The completion of the Phase 1 trade deal with the United States has resulted in a ferocious rally of the RMB against the dollar. Why not keep a slightly weaker RMB exchange rate as an additional lever of monetary easing? In addition to countercyclical measures, the Chinese government could implement a moratorium on tax filings for SMEs or waive certain mandatory contributions, such as social security and housing provident fund, for six months or even longer. Moreover, it could also step in via government procurement. In short, China has ample policy leeway to help SMEs.

Spillover unlikely to change global inflation dynamics significantly

Based on our baseline scenario—which can be summed up as a sharp slowdown of consumption in Q1 but higher pent-up demand in H2 propelled by countercyclical measures—spillover effects will be mainly seen in economies that have either close links with China (e.g., Australia, Southeast Asian countries, and Korea) or a strong dependency on Chinese tourism (e.g., Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China, Vietnam, and Thailand). However, even for these two types of economies, the impact is expected to be transitory (Thailand’s GDP growth could be reduced by 0.2 percent in 2020 on the back of the virus). In the case of Australia, whose exports to China are about one-third of its total exports, China’s investment cycle will be profoundly felt. Moreover, China’s tourists and demand for education (about US$5 billion in 2019) have fueled the Lucky Country’s consumption boom. The impact of the virus could result in estimated economic cost of US$4 billion, according to Deloitte Access Economics, but it has prompted the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to ease monetary policy on March 3.13

In conclusion, the epidemic, whose duration remains difficult to predict, has prompted us to revisit our key forecasts for the Chinese economy.

So far, revisions in the market on GDP growth range from 0.1 percent to 1.2 percent. We are more sanguine and see a different growth trajectory—a bad Q1, a flat Q2, and a V-shaped recovery in H2. Estimated GDP growth of 5.3–5.5 percent is therefore a more plausible scenario. There is one caveat: Even if the coronavirus is behind us, commitment to the Phase 1 trade deal could well become a focal point during this US election year. Unlike in 2003, how Beijing will reflate the economy will have a profound global impact this time around. This is why the guiding principle for stabilizing the economy and ultimately ensuring social stability is to focus most fiscal relief on SMEs, which are more vulnerable to economic shocks.

We are more sanguine and see a different growth trajectory—a bad Q1, a flat Q2, and a V-shaped recovery in H2.

Sectoral impact of coronavirus

In line with our top-down views, the epidemic will have a limited impact on most industries. The consumer sector will bear the brunt of it in February and March. Lost revenues in catering, retail, travel services, and property transactions—revenues have been virtually zero since late January—will not be fully offset by likely higher pent-up demand in future. But consumers’ psyches seem to remain intact, as evidenced by the strong rally of the stock market dominated by individual investors.

The outbreak has highlighted the importance of e-commerce at a time when consumers are confined to their homes. While e-commerce has empowered Chinese consumers, its last-mile constraint is also being heightened amid the outbreak. On balance, we are relatively sanguine about manufacturing on the basis that corporate capex spending is expected to stay intact, but auto sales could see at least a 5 percent decline compared to our previous forecast of a flat growth in 2020. Some sectors will benefit from the virus due to inadequate investment. Shortages in medical supplies and poorly equipped prevention of infectious diseases could lead to an investment boom. We also see higher investment in online education, online entertainment, and telecommuting platforms.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the economics collection

-

COVID-19 and the investment management industry Article5 years ago

-

A view from London Article1 day ago

-

Brazil economic outlook, March 2025 Article4 weeks ago

-

Global economic outlook 2021 Podcast4 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q1 2025 Article2 weeks ago

-

India economic outlook, January 2025 Article2 months ago