Seven lessons COVID-19 has taught us about data strategy How governments can maximize the value they derive from data

12 minute read

30 September 2020

Data has played a major role in governments’ efforts to combat the effects of COVID-19. Several key lessons have emerged that can shape governments’ data strategy even beyond the pandemic.

Data has enabled rapid pandemic responses

Data drives better decisions. Governments are not new to data-driven decision-making—their efforts to use data to replace intuition with objectivity span decades.1 In the current COVID-19 crisis, too, governments have quickly reacted to available data and developed strategies to combat the effects of the virus on people, governments, and the economy. Using data, analytics, and emerging technologies, governments made informed policy decisions to enforce restrictive protocols such as travel bans, school closures, quarantine measures, and social distancing to reduce the spread of the virus. In addition, data has informed policy decisions around the release of economic aid, reopening of cities, improving public health capacity, and much more.2

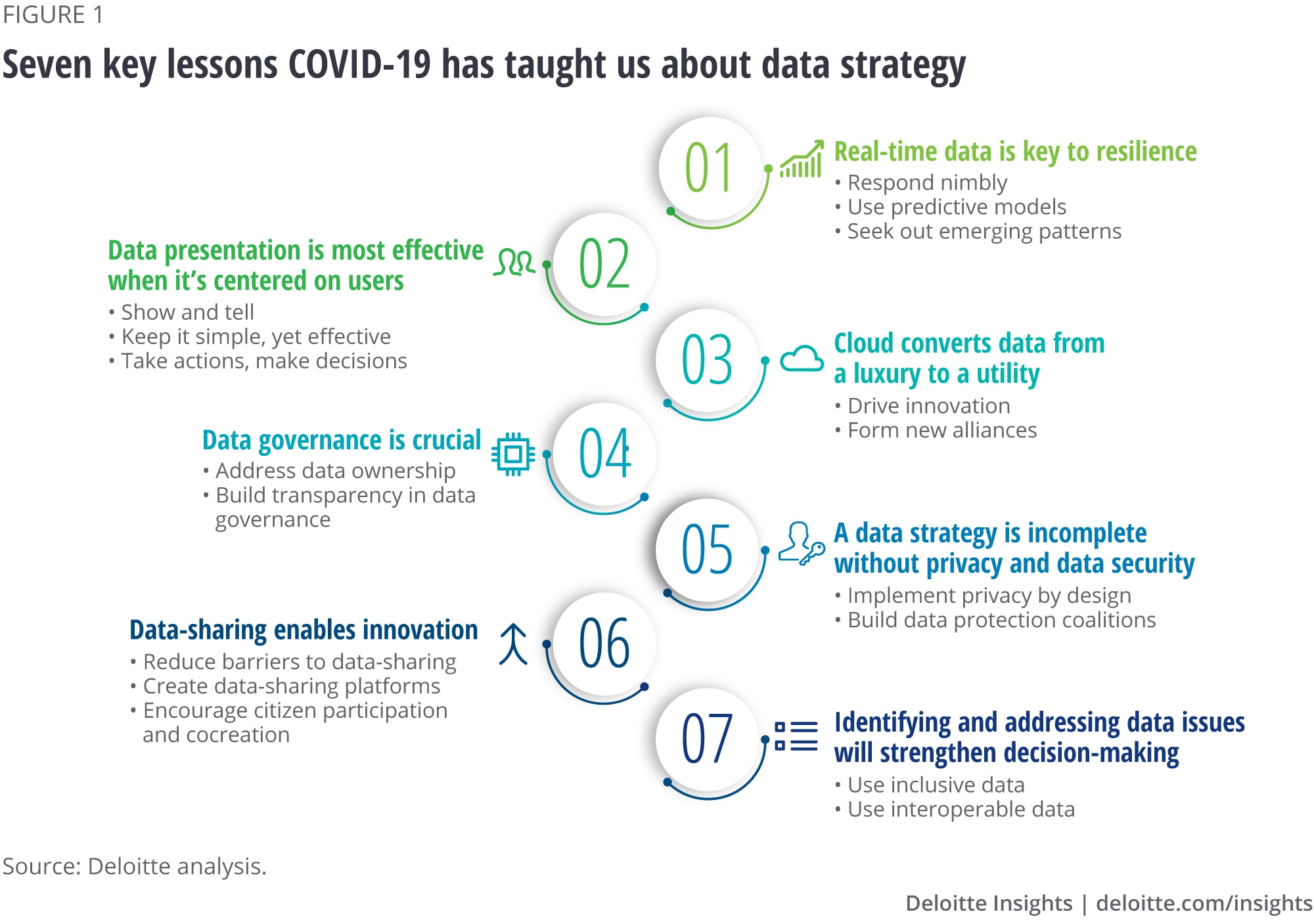

This response has highlighted some key data strategy lessons for governments. From the collection, expiration, and presentation of data to governance and privacy issues, the following seven lessons (figure 1) have emerged postcoronavirus:

- Real-time data is key to resilience

- Data presentation is most effective when it’s centered on users

- Cloud converts data from a luxury to a utility

- Data governance is crucial

- A data strategy is incomplete without privacy and security

- Data-sharing enables innovation

- Identifying and addressing data issues can strengthen decision-making

Learn more

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte‘s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

This article provides a quick look into how these principles have helped tackle the pandemic and brought about a change in the thinking of governments when it comes to data strategy.

1. Real-time data is key to resilience

To address current uncertainties, governments have accelerated more real-time, data-intensive approaches.3 These approaches leverage available economic and health data to track and model the spread of the virus, develop therapeutics and vaccines, and manage health care capacity, while also helping ensure a safe passage back to the new normal.

Real-time or “high-velocity” data can be used in multiple ways.

Respond nimbly

Governments have tapped into fast-moving, real-time data to respond quickly. Taiwan, for example, was able to combat the spread of COVID-19 with the help of digital democracy tools focusing on three principles: fast, fair, and fun. The government quickly responded to the threat by testing flight passengers from Wuhan as early as in December 2019. It also activated the Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC), an effort established in 2003 after SARS, to ensure resilience against the COVID-19 spread. To avoid shortages of face masks, it mapped the real-time availability—updated every 30 seconds—of masks in 6,000 pharmacies across the country. Finally, it quickly addressed rumors and conspiracy theories on social media—within two hours—to avoid the spread of misinformation.4 These tools were key in keeping infection rates in the country as low as 45 infections per million people.5

Use predictive models

A host of governments, academic, and health care institutions developed models to predict the virus spread. For example, The US Department of Homeland Security’s National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center developed a predictive modeling tool to evaluate the natural decay of the virus on surfaces. It developed an online calculator to assess the decay of the virus with a combination of environmental factors such as relative humidity, UV index, and temperature.6

Seek out emerging patterns

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) can enhance the usefulness of data by identifying patterns. To assist researchers in tracking changes in the genetic structure of the virus, a group of health care specialists developed an innovative COVID-19 genotyping tool. Using data from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data’s COVID-19 data set, the tool compares samples from individual hospitals with global samples. The AI-driven platform takes minutes to generate results—an effort that would have previously taken days. The results provide an understanding of the outbreak and the genetic pattern of the virus, and are assisting in the development of therapeutics and vaccines to fight the virus.7

For a real-time data approach to be effective, processes should be enabled by digital systems that produce data on a real-time basis. Those not yet on the digital transformation journey should move in that direction.8

2. Data presentation is most effective when it’s centered on users

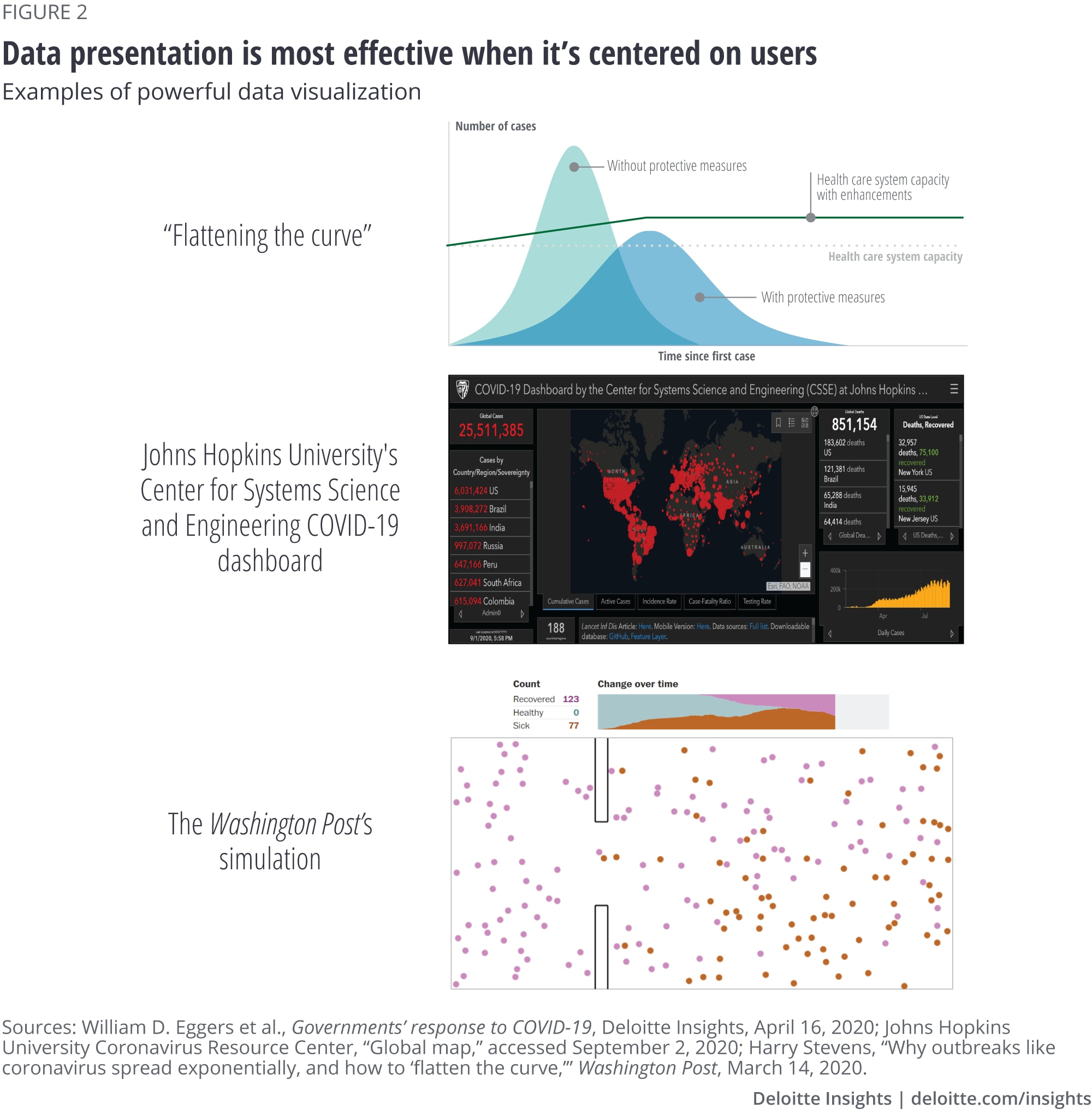

Using the basic principles of data visualization, governments and other institutions are working to make COVID-19 data more easily understandable and accessible.9 With COVID-19, we’ve seen the power of a good visualization to go viral and change behavior. Some popular examples include “Flattening the curve,”10 the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 tracker,11 and the Washington Post’s animated-dots simulation that showed the viral spread in humans over a period of time (figure 2).12

Several key takeaways have emerged from leading examples of COVID-19-related data visualization.

Show and tell

The human brain processes images 60,000 times faster than it does text.13 This means that data shown on a map is more meaningful and can be processed with greater efficiency than numbers on a spreadsheet. The Washington State Department of Health displays important COVID-19 information using visualization tools and metrics on its website for citizens’ and policymakers’ better understanding.14

Keep it simple, yet effective

Data collected and published regularly by government should be designed keeping the end users in mind. It should be simple and quick to understand, yet powerful and clearly conveys the desired message.

Take actions, make decisions

The end goal of data presentation is to improve decision-making and take action. National dashboards should allow users to compare between countries and regions on the same graph, providing a bird’s-eye view of the situation. The COVID-19 Healthcare Coalition’s COVID-19 Decision Support Dashboard organizes a large amount of vital, complex data into red, yellow, and green indicators that guide reopening strategies for governments and businesses. Additionally, it allows users to tailor their search to focus regions, facilitating comparison and enabling insights on how areas are coping and the effects of policy changes over time.15 The value of data is determined not by the data itself but by the message conveyed, decisions made, and actions taken.

3. Cloud converts data from a luxury to a utility

Cloud’s importance has also been elevated as a result of the pandemic. Many governments had to abruptly shift to cloud to allow telework, ensure uninterrupted functioning of critical tasks, and provide real-time data updates on the spread of the virus. A sudden transition to a virtual environment has led to a massive increase in the amount of data stored on the cloud.

The pandemic has nudged governments to increasingly use the cloud for a host of other reasons.

Drive innovation

The US Department of Defense created a cloud-based health information management system to build “virtual critical care wards” where COVID patients can be admitted to field hospitals around the country as necessary. The patients can then be monitored with the help of local sensors and wearable devices by a tele-connected critical care team.16

Form new alliances

A move to cloud-based tools has accelerated information-sharing and increased connectivity across the ecosystem. A number of organizations including The Future Society, Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI), and UNESCO joined forces to organize data collected on the pandemic globally, to assist world leaders to make better decisions and take actions.17

4. Data governance is crucial

The current pandemic has highlighted several data usage concerns and raised important questions about data governance, driving pressures for robust data governance frameworks that include data ownership and transparency.

Address data ownership

Data control and ownership is an ongoing concern; one study found that 79% of individuals want to be informed when their data is shared.18 Establishing frameworks to determine the purpose of the data, who manages it, and when or how it can be captured and stored can make data usage more ethical and effective, even under the pressure of a pandemic. For example, in the COVID-19 app of the UK National Health Service (NHS), the Department of Health and Social Care, along with NHS England and NHS Improvement are the designated data controllers that decide the purpose of data collection, whether data should be further shared, the duration for which the app can retain the data, and more.19

Build transparency into data governance

Transparency raises trust and increases the likelihood of compliance with rules and guidelines. When Singapore rolled out its contact-tracing app TraceTogether, the government was transparent about the logic, code, and algorithm used. Additionally, a policy brief and a government report explaining the rationale behind the app, the protocol, and the codebase was published to facilitate an open review.20

A “purpose-built” system should show users what data is being collected and how it is being used, as well as outline the ability of the citizen to control both. Going forward, with user controls, citizens can adjust how much data they wish to share and for what benefits with different government agencies. This could help increase citizens’ willingness to part with some privacy and share data for the greater good.21

5. A data strategy is incomplete without privacy and data security

With vast troves of personal data being collected by governments, there has been obvious concern about data protection. Since the pandemic exploded in early 2020, instances of data breaches, phishing scams, ransomware attacks, and frauds targeting government, health care, and citizens have been on the rise.22 Cyberattacks reported to the FBI increased 400% in the early days of COVID-19.23 In April, the United Kingdom's National Cyber Security Centre took down 83 phishing attempts within a day of introducing its new suspicious email reporting service.24 Due to the increasing level of concern, data security and privacy have to be a part of government’s DNA.

Implement privacy by design

Privacy is an essential component of data strategy in the post-COVID world. The concept of privacy by design aims to protect individuals’ privacy by incorporating it upfront into the design of technologies, processes, and infrastructure.25 For example, Google and Apple have joined hands to help the US health authorities control the spread of the virus through their app with privacy built into the system. The privacy steps include anonymizing data, use of cyclic keys (instead of static) to protect identity, and explicit user consent to upload activity data to the cloud.26

Anonymizing data by either encrypting, removing, or replacing sensitive data within the data sets, while still ensuring the essence of the data set, is a common approach used to protect privacy. For example, in Belgium, telecommunication operators are providing mobile-location data to be combined with health data to generate a collective anonymized data set to guide the government’s response to COVID-19.27

Build data protection coalitions

Staying on the right side of legal, ethical, and privacy concerns requires constant effort and monitoring by governments, citizens, and the private sector. For example, Estonia sought assistance from the private sector to develop a contact-tracing app that protects citizen privacy according to guidelines from the European Data Protection Board.28 In another example, the Global Privacy Assembly, comprising 30 data protection regulators across countries, launched a COVID-19 taskforce to address governments’ privacy concerns, along with promoting innovation through data to battle the pandemic.29

With extensive collection of personal data in recent times, the need for stronger data privacy laws has become more urgent in many countries. For example, two federal COVID-19 privacy bills—the Public Health Emergency Privacy Act and the COVID-19 Consumer Data Protection Act—were introduced in the US Congress to help ensure transparency of data collection after user consent, and restriction on data usage.30

6. Data-sharing enables innovation

The pandemic has pushed governments to evolve existing data-sharing and interoperability norms to accelerate cross-sector and cross-border collaboration, ultimately fostering innovation as well.

Reduce barriers to data-sharing

Some countries established special data-sharing frameworks to respond to the pandemic. For example, until the pandemic ends, the Italian government is following a special legal framework to allow collection and sharing of health data by public health institutions and private players that are a part of the national health ecosystem.31 Such arrangements provide an opportunity for governments to reexamine their existing data-sharing processes and realign them for the future.

Create data-sharing platforms

The US National Institutes of Health introduced a central secure repository with COVID health records of numerous patients in the country to help researchers understand the behavior of the virus and develop treatments effectively. The platform gathers medical records from health providers in the country and organizes and standardizes the data to make it accessible to researchers.32

Encourage citizen participation and cocreation

In Germany, the National Disease Control Center’s smart devices app allows citizens to voluntarily donate personal data such as heart rate, temperature, and sleep patterns. The data is then anonymized and used to predict early symptoms. The insights allow health authorities to track patients all the way down to their postal codes.33 In Taiwan, the government’s collaboration platform, vTaiwan, brought together citizens, academia, and software developers to develop various tools to effectively respond to the virus; the real-time face mask maps mentioned previously were an outcome of the collaboration.34

Governments should continue to be open to nontraditional methods of data collection for better and accurate policy-making in the post-COVID world.

7. Identifying and addressing data issues will strengthen decision-making

Data-driven decisions are only as reliable as the data itself. The pandemic highlighted significant drawbacks in data currently available to governments, such as biases, reporting inconsistency, and lack of completeness. Analysts and decision-makers should identify and correct these data issues as they make critical decisions that can impact people’s lives. For example, the virus affects men and women differently, which should guide vaccine development—but data dashboards often show no gender breakup in the cases.35 Data should, ideally, represent race, age, ethnicity, gender, and living and social conditions to avoid inequality and bias, and facilitate better decision-making.

Use inclusive data

To ensure its pandemic response policy was inclusive, the Italian government included a member of the European Disability Forum in the taskforce while designing phase two of reopening.36 The UK Office of National Statistics is adapting existing surveys by making them more inclusive to understand the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable populations; the office is trying to collect new data, in addition to the census data, on disabled populations, ethnic groups, and others.37

Use interoperable data

With so much rapid change on the ground, to avoid biases and ensure reliability, data should be collected from multiple sources. Existing and new data standards can also reduce data disparity. For example, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) is a standard used by many health care organizations for managing and reporting health data. In May 2020, to fast-track electronic reporting of cases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed an app based on the FHIR standards. The new tool added COVID test results to a patient’s electronic health record and enabled health care providers to automatically send patients to public health departments without human intervention.38

The pandemic has shown once again that data is one of government’s greatest assets. While data is available in abundance, governments need integrated and holistic data strategies to maximize the value they derive from the data. These seven key lessons from the COVID-19 response provide the opportunity for governments to refresh and strengthen their existing data strategies.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Read more COVID-19 content

-

Transforming government post–COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the virtualization of government Article4 years ago

-

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

Governments’ response to COVID-19 Article4 years ago