Surviving the pandemic budget shortfalls A playbook for state and local governments

41 minute read

09 September 2020

US state and local governments face severe budget challenges following the COVID-19 pandemic. Three types of strategy levers can help them survive the short term and possibly thrive in the long run.

Key findings

Introduction

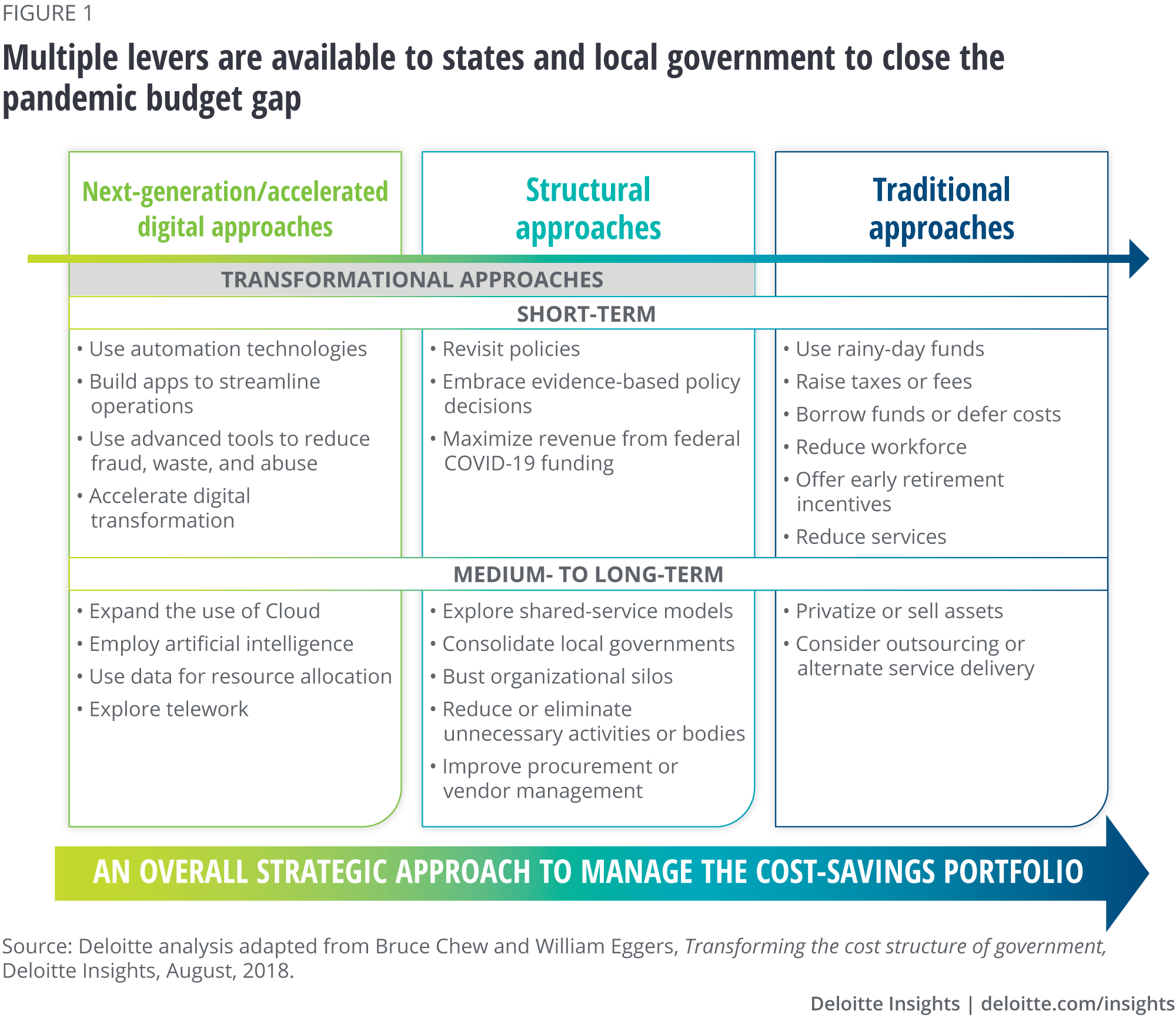

Owing to the sudden pandemic-driven revenue declines and increased costs, state and local governments are almost certain to be looking for ways to close budget gaps significantly in the coming months. Three types of approaches can be considered (figure 1), all of which are likely to play a role in addressing the fiscal crisis:

- Next-generation/accelerated digital: These employ tools and technologies to fundamentally alter the economics of government. They may require some investment but offer the potential for higher returns, as much as tenfold. These are not the huge system overhauls of the past—recent advances in technology make transformational shifts also possible within shorter timelines and more reasonable budgets.

- Structural: These approaches pursue substantive, structural changes to lower costs. They involve changes designed to improve efficiency and make better use of resources.

- Traditional: These seek to balance the books without fundamentally changing the cost equation. Instead of lowering costs, these approaches shift costs—to taxpayers, employees, citizens, or to the future. These generally generate immediate impact.

View approaches

- Use automation technologies

- Build apps to streamline operations

- Use advanced tools to reduce fraud, waste, and abuse

- Accelerate digital transformation

- Expand the use of cloud

- Employ artificial intelligence

- Use data for resource allocation

- Explore telework

- Revisit policies

- Embrace evidence-based policy decisions

- Maximize revenue from federal COVID-19 funding

- Explore shared-service models

- Consolidate local governments

- Bust organizational silos

- Reduce or eliminate unnecessary activities or bodies

- Improve procurement or vendor management

- Use rainy-day funds

- Raise taxes or fees

- Borrow funds or defer costs

- Reduce workforce

- Offer early retirement incentives

- Reduce services

- Privatize or sell assets

- Consider outsourcing or alternative service delivery

The perfect storm

Learn more

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

How big is the fiscal problem facing US state and local governments due to COVID-19?

The full extent won’t be known for some time and will depend on the course of the virus. Early indications are that the budget crunch will be extensive, and the impact will play out over multiple years.

Government revenues depend on the overall economy, and actions to stem the spread of the virus have drastically reduced economic activity. The economy faces multiple unknowns, including the trajectory of the pandemic and the return of consumer confidence.

The pandemic has reduced revenues, added emergency responsibilities to government, and increased operating costs, since many activities are more costly due to the virus.

Recent government revenue forecasts have been particularly challenging due to the uncertainty of the virus. All levels of government are likely to be hard hit, however.

States: According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of July 2020 most states with available forecasts were anticipating FY 2021 revenue drops of 10–20%.1 States may be better or worse positioned to weather this sort of storm depending on how hard they were hit by the virus, the state of their rainy-day accounts, and how well-funded their pension funds are.

Counties: According to the National Association of Counties, county governments collectively face a budget shortfall of US$144 billion in FY21, which includes US$114 billion in lost revenue and US$30 billion in added expenses.2

Cities and towns: According to a 2020 survey by the US Conference of Mayors and National League of Cities, 88% of municipalities anticipate painful reductions in revenue this year. The economic downturn is expected to hit almost every revenue source, including permit and utility fees and property and sales tax.3

Other: Local government authorities, including transit agencies, ports, and airports, are also likely to face revenue shortfalls.

And it’s not just about declining revenues. The COVID-19 pandemic is also saddling state and local government with a host of added costs. State and local governments are on the front line of pandemic response and these increased costs are expected to include:

- Public health response: This includes population health monitoring such as virus and antibody testing as well as tracking capabilities; health system monitoring and support, to ensure hospitals have needed supplies, monitor the availability of beds, ensure hospitals are fiscally sound; and managing the phased reopening including mechanisms to monitor and enforce a range of protocols in offices, restaurant, hotels, public buildings, and other places.

- Higher government operating costs: Government’s own operational costs will likely increase as they install new protocols to protect both their own employees as well as members of the public they serve. These protocols may include tasks such as regular health and temperature testing of government employees and citizens requiring in-person services, changes to government office space density, and enhanced cleaning protocols for mass transit vehicles. From schools to prisons, measures to address COVID-19 are expected to increase costs. In addition, as telework continues, enhanced cybersecurity, IT, and call center support may also increase.

- Surges in demand for government services: Government will see increases in demand due to COVID-19, not only in obvious areas such as unemployment insurance, Medicaid, and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits but also in health and human services, mental health, and backlogs from activities put off during the crisis.

The economic downturn is expected to hit almost every revenue source, including permit and utility fees and property and sales tax.

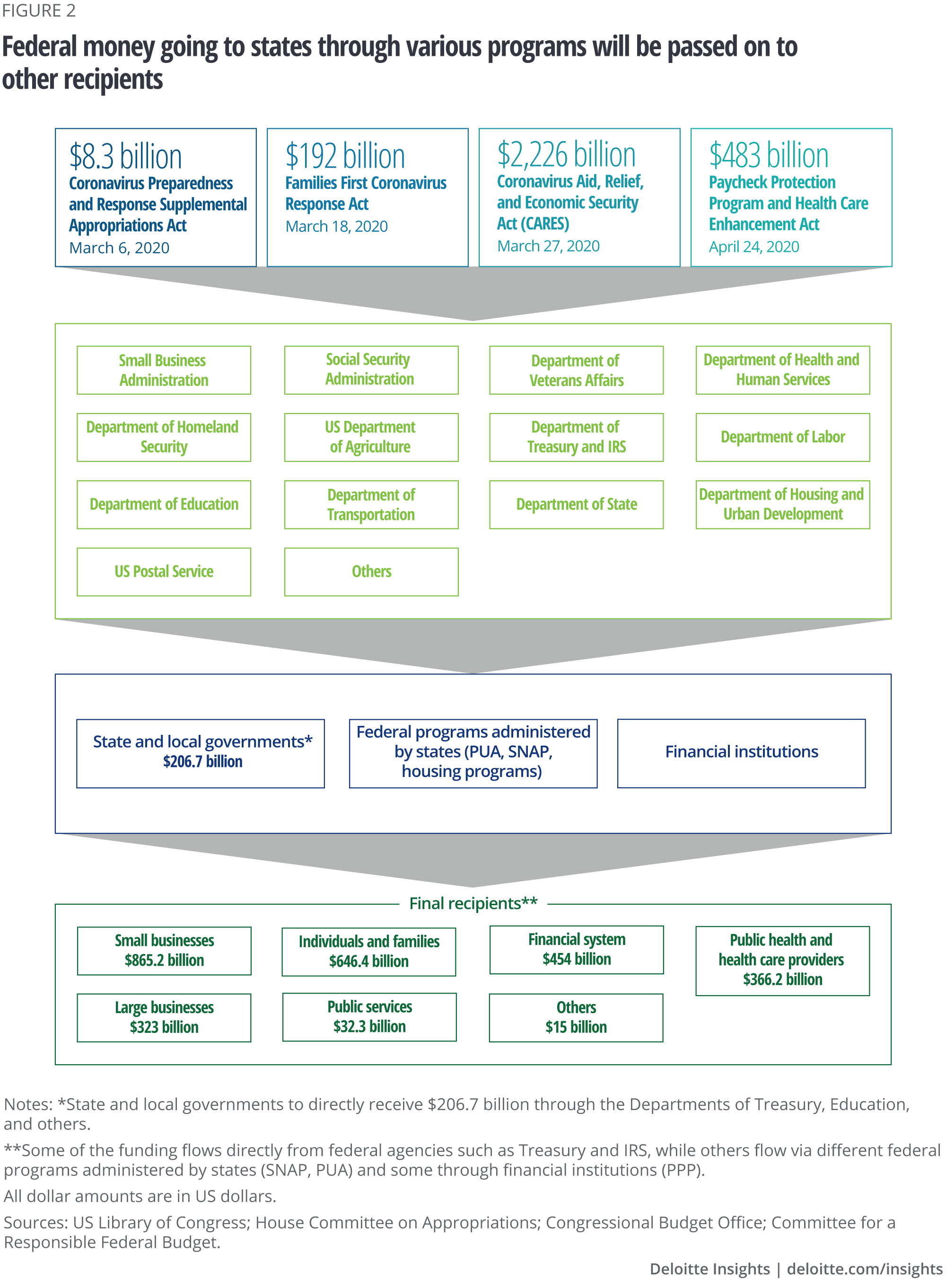

One source of assistance is the federal government. While much of the funding in the CARES Act and other early federal relief packages targeted individuals and businesses, some was earmarked for state and local governments (figure 2). While additional federal aid is likely, it’s not expected to be enough to plug the hole. Additionally, federal funds that are targeted to specific types of expenses may not be able to compensate for the full range of state and local government expenses or lost revenue.

The following sections detail the next-generation, structural and traditional approaches available to state and local governments to lower costs and close the budget gaps.

Next-generation and accelerated digital approaches

Sometimes big problems require big solutions. These next-generation and accelerated digital approaches offer the opportunity to foundationally alter the economics of public sector operations. Just as we have seen companies use emerging technologies to generate enormous market value, these innovations can help create tremendous public value. These approaches may require technology investments or changes in legislation or organizational culture. Ultimately, however, they can potentially repay the investment many times over.

View approaches

Short-term

Use automation technologies

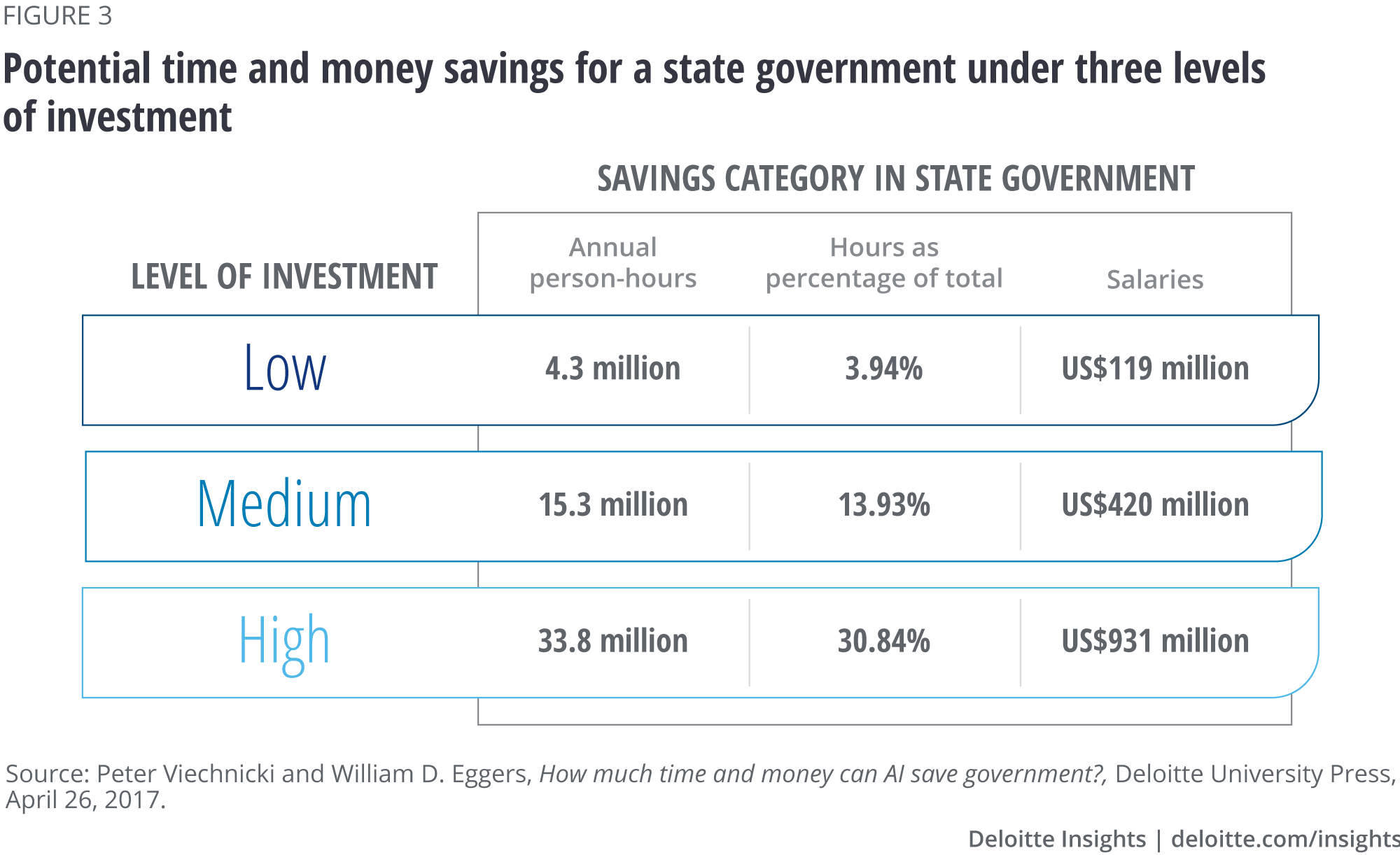

When most people think about technology solutions, they imagine big, high-cost systemic overhauls. Robotic process automation (RPA) however, can be a low-cost, lightweight technology solution that automates routine, low-value activities, freeing frontline employees to handle higher-value, more mission-focused tasks (figure 3).

Many state and local government workers spend millions of hours doing routine activities. Government employees of one large Midwestern state spend an estimated 10% of their time recording and documenting information. A Deloitte study estimated that automation in that state could save more than US$931 million per year.4

There are several examples of the potential benefits of RPA for governments. In New Mexico, the Department of Health and Human Services uses bots to make routine determinations regarding the benefits for which citizens qualify. In Ohio, bots are used to determine eligibility and automatically enroll newborns in Medicaid programs, saving time and streamlining the process.5

Figure 3 shows possible savings both in terms of dollars and worker hours. That’s because automation savings don’t necessarily mean layoffs. Especially in light of the increase in responsibilities for government due to the pandemic, automation would allow governments to shift employee effort away from routine activities and apply them to other priority responsibilities.

Build apps to streamline operations

You may be familiar with the phrase “there’s an app for that.” Well, in government, there are still a lot of processes that don’t have their apps yet—but that is changing.

For many years, Pennsylvania’s Department of Transportation managed the payroll of its highway maintenance workers using paper timecards. This paper-based process had an error rate of more than 80%. In addition, the process was tedious and time-consuming for staff. To streamline operations, in 2019, the department launched a new mobile app that allowed supervisors to log and manage the work schedules of workers. The app, which took only six months to develop, operates in real time, making it much easier for supervisors to manage work schedules. The department expects the new app to generate an annual saving of approximately US$7.5 million.6

There are many examples of digital apps in state governments that streamline operations. In 2017, the state of Washington launched mobile apps for child welfare services, looking to make it easier for those in the field to enter and access information.7 In general, such apps don’t require massive investment and can generate long-term cost savings while enhancing service quality.

Use advanced tools to reduce fraud, waste, and abuse

As the saying goes, “A penny saved is a penny earned.” If government can avoid making an improper payment, that means another dollar available to achieve the mission. Fortunately, new tools are emerging that can help state and local government to reduce fraud, waste, and abuse.

Technology tools such as data analytics may be one of the most cost-effective investments to reduce improper payments.

New data analytics tools, including social media monitoring and artificial intelligence (AI), can help to reduce improper payments. This is welcome news, since improper payments can be quite costly. In March 2020, the Government Accountability Office estimated that improper payments by federal agencies totaled US$175 billion in 2019,8 more than the 2019 state budgets of Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina combined.9

Technology tools such as data analytics may be one of the most cost-effective investments to reduce improper payments. The Office of Inspector General within the US Department of Health and Human Services indicates that the department saves US$5 for every US$1 invested in using data to find fraud. In one such effort, data analytics was able to uncover US$1.3 billion in criminal activity related to fraudulent prescribing of opioids.10

Soft-touch behavioral interventions, commonly known as nudges, can also help governments reduce fraud by encouraging accurate compliance. For example, to reduce overpayments in its unemployment insurance program, the New Mexico Department of Workforce Solutions designed simple pop-up messages to claimants. These messages nearly doubled the self-reported earnings, lowering improper payments from 5% in 2015 to 2.9% in 2016.11

If a state or municipal government hasn’t reviewed its anti-fraud efforts lately, it may discover that new technology and other approaches are now available that can generate meaningful savings.

Accelerate digital transformation

Digital workflows have the potential to dramatically reduce costs, often while boosting customer satisfaction. The business world has seen industry after industry revolutionized by digital, and while governments certainly have shifted more to online services, there are still plenty of additional opportunities to digitize processes.

When citizens aren’t using digital self-service tools to conduct business, public sector employees spend more time providing customer service on the phone or in person, which drives up operational costs. A recent Harvard Business Review study estimated that it cost businesses between US$7 and US$13 for every live service interaction.12 With government’s large customer base, going digital can translate to huge savings.

Self-service digital tools allow government organizations to devote fewer resources to call centers and field offices, and can also reduce error rates.13 States such as Massachusetts and Pennsylvania have shifted to electronic toll collection, making the process more seamless.14 Texas Health and Human Services Commission launched a mobile app to integrate eligibility and verify documents for all federal and state programs on one platform, improving the service delivery of these programs.15

In some cases, digital delivery models can help government raise additional revenue through improved services. For instance, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources used Google Maps technology to launch the Georgia Outdoor Map, which provides information to citizens on nature venues for hiking, fishing, and so on. While the information had been previously available, many citizens had found it difficult to access. The new digital service has led to an increase in the number of park reservations per day, which is expected to generate an additional revenue of more than US$200,000 per year for the department.16 A similar effort by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation has increased park reservations by 5% and cut costs by US$100,000 per year due to better service delivery.17

Transformational trends in government today

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Deloitte Center for Government Insights identified a set of nine trends that are shaping governments today.18 Government Trends 2020 highlighted important trends that have begun to penetrate the heart of government. While the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted government focus temporarily, these trends were gaining momentum because they offer the chance to provide better services at lower costs. Governments dealing with the pandemic and budget crises in the short term should keep these trends in mind when making decisions.

- AI-augmented government: Cognitive technologies that are upending the consumer world are coming to a government near you. The way governments respond to AI, both as a regulator and as a user, is expected to shape our societies and even geopolitics for years to come.

- Digital citizen: Unique digital identifiers open the door to integrated data and a seamless citizen experience, enabling dramatic leaps in service quality, massive efficiency gains, and the move to a digital delivery model.

- Nudging citizens for good: As the field of behavioral economics advances our understanding of how people make choices, “nudging” is replacing incentives and punishments—promising lower costs, better outcomes, and an enduring respect for human autonomy.

- The rise of data and AI ethics: Information is power, and power can be used for good or ill. Governments will play a major role in the rise of data ethics, not only as the “owner” of massive amounts of data but also as a regulator of corporate data use. As smart machines know more about us, privacy, equity, and transparency should guide their operations.

- Anticipatory government: Data analytics, scenarios, and simulations allow us to target likely problems before they erupt. From spotting fraud to combatting the opioid epidemic, an ounce of prevention really is worth a pound of cure, especially in government.

- Cloud as innovation driver: Cloud computing is already a key enabler for other innovative trends (for example, nearly 87% of companies using AI do so in the cloud19). Because cloud provides a mechanism to connect technology developers and users, its role as a foundation for innovation will likely only become more important (almost 50% of new software today is developed only in the cloud20).

- Innovation accelerators: Iterative, reality-tested, safe experimentation is critical to innovation, in everything from health care to currency. Accelerators, incubators, and government “labs” are part of the emerging trend. In addition, regulatory sandboxes are a way to allow private innovations much greater flexibility within a limited space.

- Smart government: As we see with smart cities, integrated, connected, and sustainable governments will deploy technology to serve citizens in a collaborative and comprehensive manner, improving everything from mobility to health care to the environment. Cities are at the forefront of the trend, but it is now coming to regions, universities, military bases, and rural communities, among others.

- Citizen experience in government takes center stage: How can large public systems deliver services that meet the needs of individuals? They can start by walking in citizens’ shoes and understanding that “one size fits all” won’t cut it. Customer experience tools can be used effectively to serve not just government’s customers but also government employees, regulated entities, and businesses.

For more information, see Government Trends 2020.

Medium- to long-term

Expand the use of cloud

IT costs are a major component of state and local budgets, and the cloud offers the potential for cost savings. By paying only for what they use, government can potentially lower operating costs and flex capacity as demand requires. Since 2011, the federal government has been pursuing a “Cloud First” and now “Cloud Smart” strategy of moving data and applications onto the cloud.21 While a 2017 survey found that cost savings is the top reason why public leaders choose the cloud,22 cloud can also improve operating efficiencies by making data sharing easier.

Another benefit of the cloud for state and local governments is to deliver services more efficiently. In Delaware, the Department of Services for Children, Youth, and Their Families moved to the cloud to improve the care delivered to children and their families. This allowed the department to more easily share data with other departments, which provided caseworkers with a more integrated view of the client, enabling them to make better and more timely decisions.23

By paying only for what they use, government can potentially lower operating costs and flex capacity as demand requires.

Employ AI

The growing toolkit of AI—computer vision, natural conversation, and machines that learn over time—has the potential to enhance almost everything government does, from education and health care to policing and transportation. AI technologies can help governments reduce costs and save money in several ways.

AI technologies can save worker time on manual processes, allowing them to move to higher-value work. For instance, paperwork is an activity that takes up a massive amount of worker time in government: A recent report found that employees at Colorado’s Child Welfare office spend 37.5% of their time only on paperwork—time that could be devoted to family support.24

AI technologies such as handwriting recognition can automate data entry. Speech recognition and automated translation can be used to enhance customer services, while optimization algorithms can assist with efficient scheduling.

AI technologies can reduce costs through real-time tracking via sensors. For example, smart streetlights can turn on or off depending on whether there are people nearby, leading to a reduction in energy costs. Los Angeles is using smart parking meters to dynamically set the price of parking based on demand, which has helped the city increase occupancy, and subsequently revenue by 2.5%.25

Finally, AI offers cost savings through better predictive capabilities. Cognitive applications, such as anomaly detection systems that employ neural networks, can understand and identify pertinent patterns in data and guide effective responses to problems. DC Water, an independent authority that manages the water supply in Washington, DC, adopted AI to reduce the cost of detecting defects in water pipelines. Autonomous robots are used to capture video of pipes, and the video is analyzed by an AI-based neural network to detect pipe defects. The new AI-based process has reduced the cost of inspection from US$7 to US$9 per linear foot to US$2 to US$3 per linear foot.26

In the coming years, AI has the potential to improve government’s operational efficiency and effectiveness in a significant way.

Use data for resource allocation

Governments manage three main categories of resources: people, physical assets, and money. Data analytics can help agencies make sense of operational data and turn it into usable insights to improve resource allocation in all three areas.

Human capital is generally the most critical resource an agency manages, often exceeding one-third of the total budget. Data analytics can help agencies decide how to deploy staff to be most effective. For instance, the New York Fire Department (FDNY) built a system called FireCast to help identify the buildings most at risk, in turn helping to prioritize inspections and deploy workers more effectively. FireCast runs algorithms using data gathered during FDNY inspections as well as from the city’s planning, buildings, environmental protection, and finance departments. Officials report that FireCast has eased workloads as well as directed inspectors to some of the city’s most fire-prone buildings, some of which hadn’t been inspected in years.27 Thanks in no small part to FireCast, New York City suffered no fire-related deaths in 2015, for the first time since 1916.28

Modern analytics tools can also help leaders make more objective decisions about investment in and deployment of physical assets. Data analytics leveraging connected sensors and real-time input from citizens, for example, can be used to optimize physical infrastructure and are a key part of a smart city. The SmartSantander project in Santander, Spain, uses this approach in real time to adjust energy use, schedule trash pickups, and even determine how much water to sprinkle on the lawns of city parks.29

The third critical resource government agencies manage is funding of outside organizations. This is handled through means such as grants, loans, and guarantees. One agency that is using data analytics to manage more than US$17 billion in grants is the US Federal Railroad Administration, whose “enterprise data store” contains relevant information on all its high-speed rail grants and helps forecast the effect of investments on outcomes.30

Explore telework

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the traditional office-based workforce. Governments’ forced shift toward a virtualized, work-from-home model demonstrated that many people could work effectively while working remotely.31 It was observed that even “in-person” interactions such as doctor visits or court appearances can be done remotely. Government’s rapid, mostly successful experiment with telework provides leaders with an opportunity to attract a younger, more agile workforce while simultaneously lowering physical infrastructure costs. On the flip side, citizens may appreciate not being required to appear in person to access services.

State and local governments can realize considerable savings by asking: In light of today’s collaboration technologies, what work can be done remotely? Some states are already considering telework as one of the cost-saving strategies for dealing with the current financial crisis. The state of Georgia, for instance, has estimated a savings of US$20 million in its FY21 budget through reduced spending on rent, travel, training, and meetings due to increases in telework.32 Similarly, the state of California is planning to expand telework for certain job classifications to reduce leased office space—and save money.33

Structural approaches

Structural approaches allow governments to save costs by changing what they do and how they do it—by enhancing operating models, building new service delivery models, and forming new delivery partnerships. However, these solutions require some amount of organizational change and may take some time to implement.

View approaches

Short-term

Revisit policies

In some cases, policy choices rooted in the distant past may no longer be appropriate due to social, technological, or political changes. Requirements to publish certain public notices in the newspaper in the internet age probably don’t make a great deal of sense. If cars were invented today, governments probably wouldn’t use a metal license plate to identify them—some sort of digital transponder could easily provide information about ownership and outstanding tickets, and be used to pay tolls, without worrying if snow or mud was obscuring the plate.

Some policy changes can generate significant cost savings with little impact. Requiring new photos on a driver’s license once every five years instead of once every two years reduces in-person transactions by 60%—with virtually no service-level impact. During the pandemic, some telehealth policies were changed, with the result that in many cases health care costs were reduced without major service issues.34

Changes to policies can also lower costs for government, and make it easier for citizens and businesses to interact with government. During the response to COVID-19, governments made a number of process and regulation changes—some of which are prompting a revisiting of the old rules. One example was the easing of rules around telehealth.35 In addition, changes were made to certain Medicaid policies, such as relaxing interview requirements for new applicants and renewing policies automatically for existing beneficiaries. A number of these changes were made rapidly as states were dealing with limited operational capacity and increased demand for health coverage.36 But the spirit of experimentation prompted by the pandemic may be an opportunity to challenge some of these policies and reimagine regulations in a way that not only save costs for government, but also result in better service delivery for citizens.

Requiring new photos on a driver’s license once every five years instead of once every two years reduces in-person transactions by 60%—with virtually no services-level impact.

Some policy changes may require legislation, while others can be accomplished through executive action. In some cases, there will be good reasons for continuing current practice, but it’s important to ask the tough questions. Leadership drives policy choices, and the imperative to reduce costs may encourage leaders to rethink policies.37

Embrace evidence-based policy decisions

Sometimes, government doesn’t know which of the various programs are delivering the most bang for the buck. Evidence-based policies can change that.

Using evidence to inform policy decisions is not a new concept. However, as data becomes ubiquitous and the power of data analytics continues to grow, implementing evidence-based policy approaches has become more feasible. Several states have been able to realize cost savings by using evidence to direct resources toward those policies that deliver results—in essence, a limited form of performance-based budgeting. Forty-nine US states have at least one formal mechanism to fund evidence-based programs.38

In the state of Washington, the Department of Social and Health Services combines data from 10 different agencies on 2.4 million beneficiaries of public assistance programs to evaluate which factors lead to better outcomes for individuals. This effort has helped the state improve health outcomes for high-risk Medicaid beneficiaries, resulting in lower costs and over US$68 million in savings for the state due to reduced nursing facility use, hospitalizations, and rehospitalizations.39

Oregon is another state using data to drive evidence-based decisions. Many of the state’s grants are directed to local public safety agencies to allow them to test strategies that reduce prison recidivism. In human services, Oregon’s Pay for Prevention initiative directs funds to evidence-based interventions; its goal is to prevent children and youth from entering the state’s child welfare and foster care systems in the first place, which would ultimately save tax dollars.40

Cities are embracing evidence-based approaches as well. What Works Cities, launched in 2015, has supported 100 US cities in leveraging data to enhance evidence-based policymaking.41

Washington’s Department of Social and Health Services’ effort has helped the state improve health outcomes for high-risk Medicaid beneficiaries, resulting in lower costs and over US$68 million in savings for the state due to reduced nursing facility use, hospitalizations, and rehospitalizations.

Maximize revenue from federal COVID-19 funding

The CARES Act included US$206.7 billion in direct aid to state and local governments.42 A thoughtful approach to applying for and using these complex funding streams can help governments maximize the funds they obtain as well as optimize the impact of these federal dollars.

To do so, state and local governments will need to understand how they might qualify for different relief packages, some of which come with an expiration date, driving states to act quickly. Funding rules can be complex, and states and local governments will need to think strategically. For instance, some spending may be eligible for different federal programs with different rules; one program may reimburse at a rate of 75 cents per dollar but have no cap, while another program may offer 100% reimbursement but come with a reimbursement limit. Additionally, a relief package under FEMA, for example, might tightly constrain eligible spending while CARES funding could accommodate a broader range of expenses.

Strategically allocating the expenses to different relief funds can make a big difference in how states benefit from federal support. Given the complex nature of the relief funds, state and local governments are facing a large accounting, tracking, and reporting effort to demonstrate how relief funds are being deployed. If they are unable to demonstrate to federal auditors that these funds were correctly used, there could be potential clawbacks and ex post facto denials of payments from the federal government. To address these challenges, states should consider creating a central project management office to coordinate relief activities across state agencies, including applying for funds, documenting their use, and reporting on the impact of the spending.

Finally, governments should identify opportunities to invest in technology with federal dollars wherever possible, since governments that upgrade their operational infrastructure, such as adopting digital technologies or migrating to the cloud, can generate long-term cost-saving efficiencies. However, the early federal relief funds largely limited state and local money to pandemic-related expenses. As additional federal funding becomes available, there may be greater opportunities to use them on technology enhancements.

Medium- to long-term

Explore shared-service models

Sharing back-office functions—such as IT, HR, finance, and procurement—can result in significant cost savings for government. Shared-service agreements can take many forms, including local agreements between two cities, counties, or school districts. In some cases, a larger city may provide surrounding municipalities with services on a contract basis. The city of Tyler in Texas, for example, entered into an agreement with the city of Whitehouse in 2018 to provide all IT-related services such as software upgrades, data backups, systems administration, and troubleshooting, at a cost of US$75,000 annually. As per Whitehouse city estimates, it would have cost US$40,000 extra annually if the city provided these services itself.43 Another example is Oakland county in Michigan, which provides IT services to around 100 agencies and departments around the state.

In other cases, a separate state entity altogether may be established to provide shared services to multiple participants. New York’s Digital Towpath is an intergovernmental cooperative that provides various e-government services to 161 mostly small towns and villages in New York state, including a website contact management system, electronic records management, and email services.44

While the focus of shared services, historically, has been on back-room activities, leaders have begun to consider mission-focused activities as opportunities for migration to other providers.45 One example is a joint effort by Gloucester and surrounding counties in New Jersey to share correctional services. Since correctional facilities include high-cost activities such as around-the-clock personnel, pooling these services resulted in savings of more than US$21 million in 2018.46

Another notable example of shared services is in the United Kingdom, where 626 shared-service arrangements between local governments have resulted in a cumulative cost savings of US$1.68 billion to date.47 These partnerships include everything from finance and procurement to fraud detection and housing services. One of the largest examples, originally called Local Government Shared Services (LGSS), was established in 2010 when Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire County Councils merged their corporate services. A decade later, the collaboration has expanded, adding a third partner council and now managing corporate services for customers across local government, health and social care, emergency services, education, and more.48

Consolidate local governments

Consolidating local governments could lower costs without impacting services. In many areas of the country, county governments often exist in a slim region between state, city, and town governments, with imprecise responsibilities. Indeed, in the late 1990s, Massachusetts eliminated most of its county governments.49

Municipal governments, too, sometimes lack the economies of scale for efficient operation. Illinois, with 6,963 governments, has the highest number of any state, and local government consolidation is being considered.50 For instance, in April 2019, Naperville township took advantage of a new state law that allows it to take over the responsibilities of road districts that are separate tax bodies in Illinois. More recently, Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker signed another law that allows McHenry County voters the right to decide if they want to absorb the county’s 17 township governments.51

Local government consolidation is not a one-size-fits-all solution, but it may offer opportunities to reduce costs with minimal impact to citizens.

Bust organizational silos

From emergency response to health care, government missions often cross agency boundaries. Silo-busting organizational changes can deliver permanent cost reduction by targeting and consolidating multiple agencies or departments that perform similar tasks. Rather than focusing on agencies, such changes organize services from the point of view of citizens and businesses.52

Integrated eligibility systems offer a good example of silo-busting. By combining the processes to determine eligibility for programs such as Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and SNAP, governments can avoid duplication of effort, potentially reducing costs while also making it easier for applicants, many of whom access multiple benefit programs.53 COVID-19 has given government an opportunity to review their operating models and think of new ways of cross-agency and cross-government collaborations.

Many state and local operating silos are rooted in federal funding mechanisms. Presently, federal funds that flow to different agencies often have a narrow focus and tight controls on how the money can be spent. Some issues—such as the opioid crisis—cross departmental boundaries, involving public health, law enforcement, education, and more, but it can be difficult to use funds in a collaborative manner. Similarly, smart cities involve transportation issues, energy, environment, and more—but often lack an integrated funding mechanism.

Challenging the prevailing approach isn’t easy, but given the challenging circumstances, a push for more flexibility could help state and local governments to serve their constituents more efficiently.

Reduce or eliminate unnecessary activities or bodies

Difficult financial circumstances are a good time to conduct an overall review of state agencies, programs, boards, and commissions to determine if there are opportunities to eliminate, redesign, or restructure any of them.

Excessive occupational licensing can create a barrier to entrepreneurship, and also create a confusing patchwork of boards to enforce these regulations. A 2012 report by Kentucky’s Legislative Research Commission found 571 boards and commissions in the state, noting that “there is no central repository of information” on these boards and “their exact cost is unknown.”54 Separate oversight bodies for various occupational licenses—each with independent staff and systems—can create hidden costs for business and government alike.

Organizational streamlining with an eye to reducing redundancy can translate to millions of dollars in cost savings. In 2019, Arkansas consolidated its 42 executive branch agencies down to just 15, resulting in US$26.7 million in savings.55

Improve procurement or vendor management

A third of state government spending goes into purchasing goods that cover everything from police cars to office stationery.56 During the early stages of the pandemic, there were instances in which government’s procurement process limited its ability to quickly procure essential medical supplies at a reasonable cost. Competing against one another to procure in-demand items from the same suppliers, some states ended up paying 15 times the usual price for medical equipment.57

Buying consortia that bring cities and counties together can help governments lower procurement rates. A digital procurement system can also substantially improve procurement processes by increasing competition, speeding transactions, reducing administrative costs and staff time, consolidating purchasing, and driving down prices. The state of Georgia, for example, has moved fully to an e-procurement system, replacing paper-based tenders. This shift has made the state’s procurement process more transparent and efficient.58

Emerging technologies have the potential to further transform public procurement to allow governments to save significant costs. For instance, AI technologies can be used to identify patterns in large volumes of data generated through purchasing and support procurement decisions. The Utah Division of Facilities Construction Management’s procurement system drew on AI capabilities to address the chronic problem of state construction projects going over budget. The system, which collects information on both price and performance, was used to objectively select the project contractor instead of relying on human judgment. It was used to procure the US$2.96 million Bridgerland Academic Training center, which was delivered on time and on budget.59

Traditional approaches

The upside of traditional approaches is that they generate results quickly and require little in the way of organizational change. The downside is that they don’t change the underlying cost structure of government, as they tend to defer costs or shift them to other stakeholders rather than streamline operations. Some of these traditional approaches will no doubt be a necessary part of an overall response to budget shortfalls, but they are unlikely to close the deficit gap on their own.

In addition, during a crisis of this sort, strong cash flow management should be an important part of the overall financial survival strategy. This may include placing restrictions on discretionary spending by agencies, deferring certain expenses, as well as requiring higher levels of approval for backfilling open positions.

Short-term

Use rainy-day funds

These funds are designed to soften the impact of economic downturns and will likely be the first place that states look to deal with the current deluge. While helpful, most state rainy-day funds will only begin to cover the shortfalls caused by the pandemic. At the beginning of the fiscal year 2020, the median rainy-day fund balance of states was 8% of their general fund expenditures.60 Unless the economy rebounds in a way that few economists expect, tapping into their rainy-day funds will still leave states facing massive budget gaps.

Raise taxes or fees

Raising the tax burden on individuals and businesses is a traditional approach to raising government revenues. On the plus side, such revenues can be generated fairly quickly. On the downside, they impose costs on individual taxpayers and businesses at a time when you want to encourage, not discourage, economic growth.61 Following the pandemic, some governments have scrapped proposals for tax increases62 while others have increased tax rates.63

Instead of raising taxes, some state governments might consider generating revenue from new sources. For example, some states have considered expanding their tax base by legalizing marijuana, casino gambling, and/or online sports gaming, which could bring additional revenue to state governments but which might not be desirable for every state. State governments could also alter policies to tax new types of online exchanges, including the shared economy and digital downloads.64 These approaches can help governments broaden their tax base and better mirror the changing economy, but must be weighed in terms of their overall impact.

Borrow funds or defer costs

Borrowing is another option, and the CARES Act sets aside US$454 billion for the Federal Reserve System to buy public and private debt, including notes issued by state and local governments.65 While borrowing could conceivably help address immediate revenue declines, this option will not be feasible for many cities and states for several reasons. Most states have legal limits on their ability to borrow for the purpose of covering operating costs. Borrowing is prohibited by law in four states—Arizona, Colorado, Indiana, and Nebraska—while in another 12 states, borrowing requires voter approval, which may not be easy to quickly obtain.66 Additionally, for states that choose to borrow, the cost of borrowing from the federal reserve may be higher than borrowing from traditional public or private markets. As a result, only one state, Illinois, has made use of federal borrowing as of June 2020.67 And while borrowing can help ease short-term pain, it creates risk for further strain on limited state resources in the future.

Governments may also choose to defer costs to the future by putting off maintenance of physical infrastructure or delaying planned upgrades to facilities.

Yet another way to shift costs to the future is through deferring contributions to pensions funds, or even through issuing pension obligation bonds. Most cities and states, however, view borrowing in whatever form as a short-term approach that merely delays the tough choices, since borrowed funds will need to be paid back with interest.

Reduce workforce

One of the most effective, though painful, short-term cost reduction measures is workforce cuts. The reason is simple: Employees’ salaries and benefits account for a significant portion of city and state costs. In 2018, the combined full-time equivalent employment of state and local governments stood at 16.6 million, and the total March 2018 payroll costs were US$82.6 billion.68 Not surprisingly, some states have already instituted hiring freezes or announced layoffs and furloughs of existing employees. According to the US Department of Labor, approximately 1.5 million state and local government employees were laid off or furloughed between February and June 2020.69 Ohio and Maryland announced hiring freezes in early April, and Pennsylvania removed 2,500 part-time workers in the same month.70 At the municipal level, the city of Los Angeles has ordered hiring freezes and 26 days without pay for all non-public-safety workers over the next fiscal year.71

Although straightforward to execute, these approaches can come at the hefty cost of service cuts and lower workforce morale. Moreover, due to seniority rules, hiring freezes and layoffs will often impact younger employees, exacerbating existing imbalances in the public sector workforce, which already skews older.72

Offer early retirement incentives

Offering early retirement incentives by increasing benefits for workers close to retirement can take some employee costs off the books and typically results in an exodus of older state workers. Unfortunately, these early retirement packages also carry some potential disadvantages. First, the retirement incentives increase future pension costs, negating potential cost savings over time. In addition, the most experienced employees tend to be the first to take the retirement package and these departing workers may leave a knowledge gap that negatively impacts operational efficiency.

Reduce services

Service reduction options range from reducing library hours and closing fire stations to cutting services for the elderly, reducing funding for anti-poverty programs, and reducing public funding for colleges and universities. The state of New York, for example, has cut US$8.2 billion from local aid to municipalities, schools, and health care programs.73 While difficult choices of this sort may be necessary in the short term, service reductions adversely impact those who rely on these programs at a time when some services may be needed most.

Medium- to long-term

Privatize or sell assets

As government grapples with this daunting economic downturn, states and localities can consider selling or leasing public enterprises and assets (figure 4). In doing so, governments can turn dormant physical capital into financial capital. State and local governments can also benefit financially by putting the assets on the tax rolls. For instance, local governments with underperforming assets such as parking lots, water facilities, and golf courses can use those assets to raise revenue.

On the downside, asset sales can be tricky, because they may require legislative approval, and it may take a year or more for the financial benefit to be realized. Moreover, selling or leasing can impact future revenue streams of government.

Consider the example of Chicago, which in 2009 was facing large budget challenges, and entered into a 75-year lease of its parking meters to a private contractor to generate immediate cash.74 The deal brought in US$1.16 billion, some of which it used to close a large operating budget shortfall. While useful at the time, today’s city leaders must now manage their budget without this revenue source.75

Consider outsourcing or alternative service delivery

In outsourcing, a service currently performed by government workers is contracted to an external provider, either a for-profit company or to nonprofits or academic institutions. For certain services, it may be possible to reduce costs without diminishing service quality with the help of outsourcing. Commonly outsourced activities include residential waste collection, janitorial services, fleet management, vehicle towing, inspections, property assessment, and school bus services.76

There are pros and cons to such outsourcing, and the process should be carefully managed to save costs without reducing service quality.

An overall strategic approach: How to close the budget gap

Governors and mayors have a broad menu of possible techniques for closing their budget gaps. But how should they tackle the challenge of executing an overall plan for budgetary recovery?

The first thing to recognize is that in many jurisdictions, the size of the budget gap, while not known precisely, is likely to be so large that “brute-force” approaches are unlikely to succeed. It probably won’t be possible to rely solely on traditional approaches such as tapping rainy-day accounts or skipping payments to the pension fund.

It’s also important to understand that closing the budget gap will be a process that will unfold over time in the midst of uncertainty. This includes uncertainty about the economy and the trajectory of the virus in different geographies. It includes uncertainty about federal recovery funds, as well as uncertainty with respect to new challenges that may arise (cyberattacks, hurricanes, global recessions, and so forth.)

This means that you can’t make a list of projects, assign them to different people, and expect to succeed. What you need is a dynamically managed portfolio of projects.

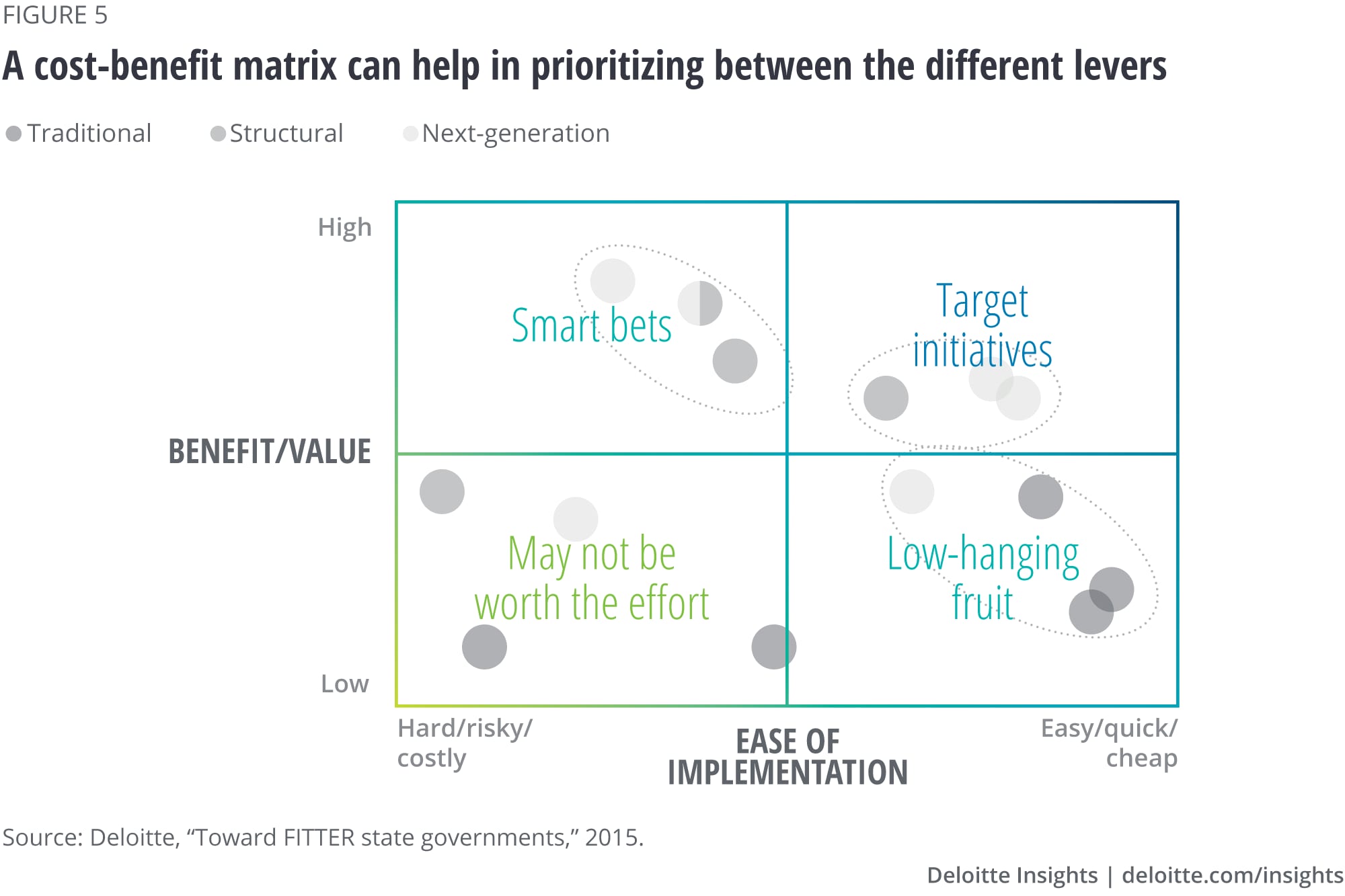

A matrix such as the one in figure 5 can help. It places possible initiatives in one of four quadrants based on two factors: their potential cost-saving benefit, and the difficulty—including cost, risk, and speed—of implementation.

Various types of initiatives—next-generation/digital, structural, as well as traditional—may appear in any quadrant of the matrix. To place projects within this matrix requires data. How much might be saved by combining two departments? Can we save money by outsourcing fleet management? It will also require an assessment of how difficult an initiative might be, and those difficulties might be technical, legal, organizational, or political. Ideas are a good starting point, but a data-driven winnowing process can surface which projects are worth pursuing.

Creating a portfolio that will balance the budget will likely require a mix of approaches—but which ideas offer the best return? Which can be achieved quickly? Which may offer large potential savings, but come with political or execution risk? Each quadrant offers different opportunities.

Target initiatives: The upper-right quadrant includes approaches that generate high value with minimal difficulty/cost, and these should get strong consideration for pursuing. Projects in this quadrant might include policy innovations that have proven effective in other jurisdictions, tech solutions with a strong track record, and the like.

Low-hanging fruit: The lower-right quadrant includes initiatives that are straightforward to accomplish but offer limited cost-saving value. These approaches also should be strongly considered, and include many of the traditional approaches (using rainy-day funds, deferring maintenance, skipping pension payments, and so on) that are relatively easy to do and generate short-term cash, but are of relatively low value in that they often incur future costs. In addition, small process innovations, minor outsourcing, and other cost-saving ideas in this quadrant can add up to significant savings.

Smart bets: The upper-left quadrant has high potential payoff but can be costly, risky, or difficult to achieve. Ideas in this quadrant often require more rigorous scrutiny to assess the potential benefits and risks. For example, merging all or parts (typically back-office operations) of multiple departments could be worthwhile—or it could be a long, difficult effort that generates little value. The same might be true for more ambitious technology implementations. Ideas in this quadrant may require some financial investment and greater participation from senior leaders—resources that are in short supply—and thus pursuing only a select number of ideas from this quadrant is advisable.

May not be worth the effort: The lower-left quadrant contains hard-to-implement ideas with limited value that are generally not worth pursuing.

A bit of good news for those looking for cost-saving ideas. In the past, technology projects were frequently high-cost, somewhat risky endeavors. Recent advances have made technical initiatives less costly, faster, and less risky than ever before. RPA and AI, for example, are two technologies where benefits can be obtained quickly, with little investment, and then scaled up.77 The investment and execution profiles of today differ significantly from just a decade ago. Similarly, new workforce and business models, such as telework and the sharing economy, offer greater flexibility and innovation potential.

Recent advances have made technical initiatives less costly, faster, and less risky than ever before.

Much more goes into a budget rationalization exercise than merely deciding which levers to pull or which projects to execute. After initially choosing which cost-saving strategies to pursue, managing the portfolio should be a dynamic process that will stretch governments’ ability to execute on a number of fronts. The four principles below should be kept in mind as governments take on this effort.

1. A vision from the top

A simultaneous top-down/bottom-up approach, in which leaders provide a high-level vision but execution is driven by the front lines, will likely be needed. This approach starts with governors and mayors setting broad parameters and constraints on which levers will be pulled. Some leaders decide that education spending can’t be reduced, or taxes can’t be raised, or that layoffs must be avoided. These leaders have been elected to set these strategic priorities and articulate a policy vision for how they want to navigate these turbulent waters. Once given these objectives, it will be up to the overall management team to produce a plan, and for multiple execution teams to deliver on that plan.

2. A team focused on closing the gap

In normal circumstances, you might be able to simply ask all your department heads to “find” a few percent in cost savings. But these aren’t normal times, for three reasons. First, agency heads are dealing with the ongoing consequences of the pandemic—from new workplace protocols to customer service backlogs to new workplace safety challenges. To expect them to manage through the crisis while also finding significant cost-saving or revenue opportunities is likely unrealistic. Second, the size of the budget gap will likely require some solutions that cross organizational boundaries—for example, shared services, some technical investments such as cloud migration, and the elimination of duplicative efforts. This is almost guaranteed with structural solutions, which, by their nature, restructure processes, activities, and responsibilities. Third, there will be important interdependencies between the initiatives. It would jeopardize success if, for example, the IT team shaves off some cloud functionality to save dollars in a way that undermines the ability of social workers in the field to quickly obtain critical information in real time. It is not just good management to think of the set of initiatives as a portfolio, the overall savings come from the integrated set inclusive of interaction effects.

To close a gap of this size, a team of skilled professionals needs to wake up every day with only one goal: How are we going to close the gap? This team should have ready access to the chief executive—and vice versa. Whether this is an internal team of public employees on loan from various agencies, an outside consultancy, or (most likely) a combination of the two, this team should see the big picture, helping department heads dig deep to execute the changes needed to meet the challenge. Over time, progress toward the goal should be tracked, and the portfolio of projects adjusted based on changing circumstances. Projects may underperform, taxes may fail to generate expected revenue, or the budget gap may grow or shrink—but a centralized project management office can track the portfolio and keep leaders informed of progress toward goals.

3. Be bold

The current budget situation is so dire that it is unlikely that state and local governments will be able to bridge the gap through a series of small jumps—whether by cutting travel and training or eliminating discretionary expenses. Those actions may be necessary, but they will certainly not be sufficient. You will need a portfolio of actions that includes a few big, bold ideas that go beyond incremental savings to allow you to cut costs by 60–90%. A central team that is willing to challenge the orthodoxies—backed by a leader who is willing to take on the sacred cows—can help discover opportunities that won’t be found by “rounding up the usual suspects.” Technology is likely to be a component of some of these bold ideas, as we have seen in the private sector, with disruptive innovation radically changing the economics of shopping, movie viewing, data gathering, and more. The “big bets” quadrant above is the usual home of such opportunities, and they can be challenging to implement.

4. Bring in outside perspectives

To find innovative bold ideas, it can be helpful to engage outside experts. Whether academics, business organizations, and other volunteer advisors, employee groups, or consultants, an outside perspective can be critical to help discover unexpected innovation. These outsiders should bring deep knowledge about how government and private sector organizations have successfully attacked similar fiscal challenges. Familiarity with emerging technologies can also be essential. These outsiders can help to generate cost-saving ideas and ground expectations in reality.

Governments that follow these principles should be in a better position to develop a comprehensive plan that not only addresses their current financial challenges but also helps them become resilient to similar events in the future.

More on COVID-19

-

COVID-19 and the virtualization of government Article4 years ago

-

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

Governments’ response to COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

The heart of resilient leadership: Responding to COVID-19 Article4 years ago