Transforming the cost structure of government What will be your agency’s Act Two on budget reductions?

16 August 2018

Government bodies will likely face significant budget constraints due to rising costs in such areas as health care and education. Because it won’t be enough to massage budgets or make one-time cuts, agencies should seek lasting cost impact with the dollars they save.

Introduction

Budget pressures, a perennial worry for many government agencies for decades, are expanding due to rising health care and entitlement costs. In 2015, 22 US states had expenditures exceeding total revenues;1 30 states faced revenue shortfalls in 2017 and 2018 or both, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.2 At the federal level, even before recent tax cuts and concerns about rising interest rates, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted that long-term fiscal projections show that “the current federal fiscal path is unsustainable.”3

Learn more

Read more from the Government and public services collection

Subscribe to receive updates from the Center for Government Insights

Faced with substantial budget pressures, organizations—both public and private—are often understandably tempted to follow a familiar script: Hiring freezes. Stopping payments to consultants. Delaying expenditures—such as maintenance and training. Redrawing organizational charts to save some overhead. We call this phase Act One.

By their very nature, however, these Act One “solutions” are temporary or one-time moves. They may address the budget challenge but not the underlying economics of the enterprise. In the future, organizations will likely face significant, sustained budget constraints due to escalating costs in areas such as health care and education. When faced with these pressures, it will no longer be enough to massage the budget or make one-time cuts. Agency leaders should script an Act Two in which they move beyond tweaking the budget to transform the economics of delivering on their missions, creating a significant and lasting cost impact with the dollars they save.

Private sector companies sometimes follow the same Act One scripts. When earnings threaten to come up short, they may deploy hiring freezes or shift expenditures. But given the ever-present turbulence in today’s marketplace—from fluctuating commodity prices, disruptive technologies, shifts in consumer demand, competitors with lower factor costs or new business models, or other factors—firms often confront the need to transform their fundamental economics.

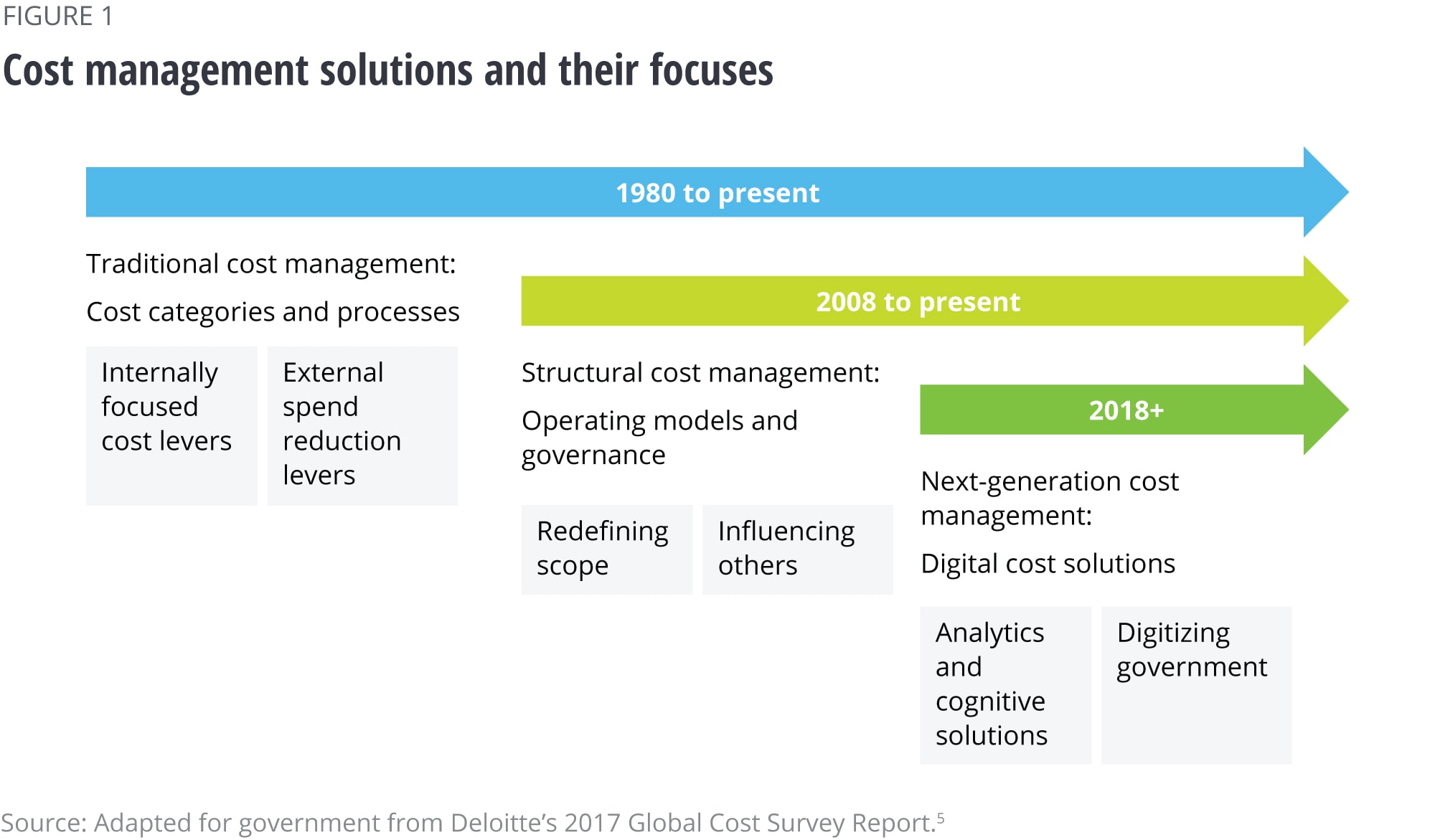

In 2017, Deloitte’s first biennial global cost survey identified three generations of cost management approaches—next-generation, traditional, and structural—that commercial enterprises have developed over the years (see figure 1).4 More than 86 percent of those interviewed (1,000+ C-level executives and senior managers from public sector and private sector organizations) expect to deploy some combination of these tools and approaches over the next 24 months. The study observed, “Cost management used to be something businesses only thought about when they were struggling. In recent years, however, it has become a standard operating practice that receives constant attention—in good times and in bad.”

Most private sector businesses have realized the benefits of the traditional cost management approach, and are now focused on mastering structural cost management and adopting next-generation approaches. And while the public sector has so far lagged behind business in cost management, a shift appears to be occurring. When faced with the likelihood of sustained budget pressure, more and more public sector leaders are considering the full suite of cost management tools that have already proven, or are now proving, their effectiveness in the commercial sector.

In this article, we do not intend to catalog all of these tools. Instead, for each of the three approaches, we identify key questions that can help government leaders identify opportunities to transform their agencies. These questions highlight high-impact opportunities that cover the full scope of the government value chain, from the supply chain, to internal people and activities, to program delivery, to citizens. We start by looking at the newest generation of cost management tools.

Next-generation cost management

A new era of digital tools is ushering in the next generation of cost management. In the past, when tasks were automated, the reduction in variable costs often came with high investment costs. Expertise was greatly valued but was difficult to scale as it resided with specific individuals and their experiences. Today, next-generation (NextGen) cost management utilizes newly developed digital tools to change the fundamentals of mission economics and work, enabling government agencies to do more with less. These flexible tools can be used to both enhance existing operations and enable entirely new approaches.

Among the most promising government opportunities in next-generation cost management are newly emerging applications in: 1) analytics and cognitive solutions, including both analytics (potentially supported by artificial intelligence, or AI) to increase effectiveness, and robotics to automate and augment labor; and 2) digitizing government, which includes cloud computing and, potentially, blockchain. Government leaders can explore the following questions to help take advantage of these developments and transform the economics of mission delivery.

How do you improve mission success without adding more people?

NextGen cost management: Digital methods and tools

NextGen cost management applies newly developed digital tools to change the fundamentals of mission economics and work. These emerging applications can both enhance existing operations and catalyze completely new approaches that can enable government to do more with less.

Sample methods and tools associated:

- Analytics and cognitive solutions

- Analytics (potentially AI-supported) to increase effectiveness

- Robotics to automate and augment labor

- Digitizing government

- Cloud computing

- IoT

- Blockchain

In 2016, the federal civilian workforce included more than 2 million employees at a cost of US$168 billion in salary and wages.6 For a large Midwestern state, the comparable dollar figure was more than US$2 billion. It is difficult to imagine a path toward transforming the economics of government that does not address the economics of people and mission. The good news is that the tools of next-generation cost management make it possible to increase and improve service in mission-focused work without needing to add staff.

Consider one perennial challenge: paperwork. At the federal level, research indicates that simply documenting and recording information consumes one-half billion staff hours each year and costs more than US$16 billion. The story for state government appears to mirror this experience; government employees of a large Midwestern state spend the same percentage of their time (10 percent) recording and documenting information as their federal counterparts do. Hiring more people would reduce the backlog and create more hours for staff to devote to higher-impact activities, but would do so at higher cost. Modern automation enabled by robotic process automation (RPA) and AI, however, can take over the burden of paperwork and other low-value activities, freeing frontline employees to handle higher-value, more mission-focused tasks.

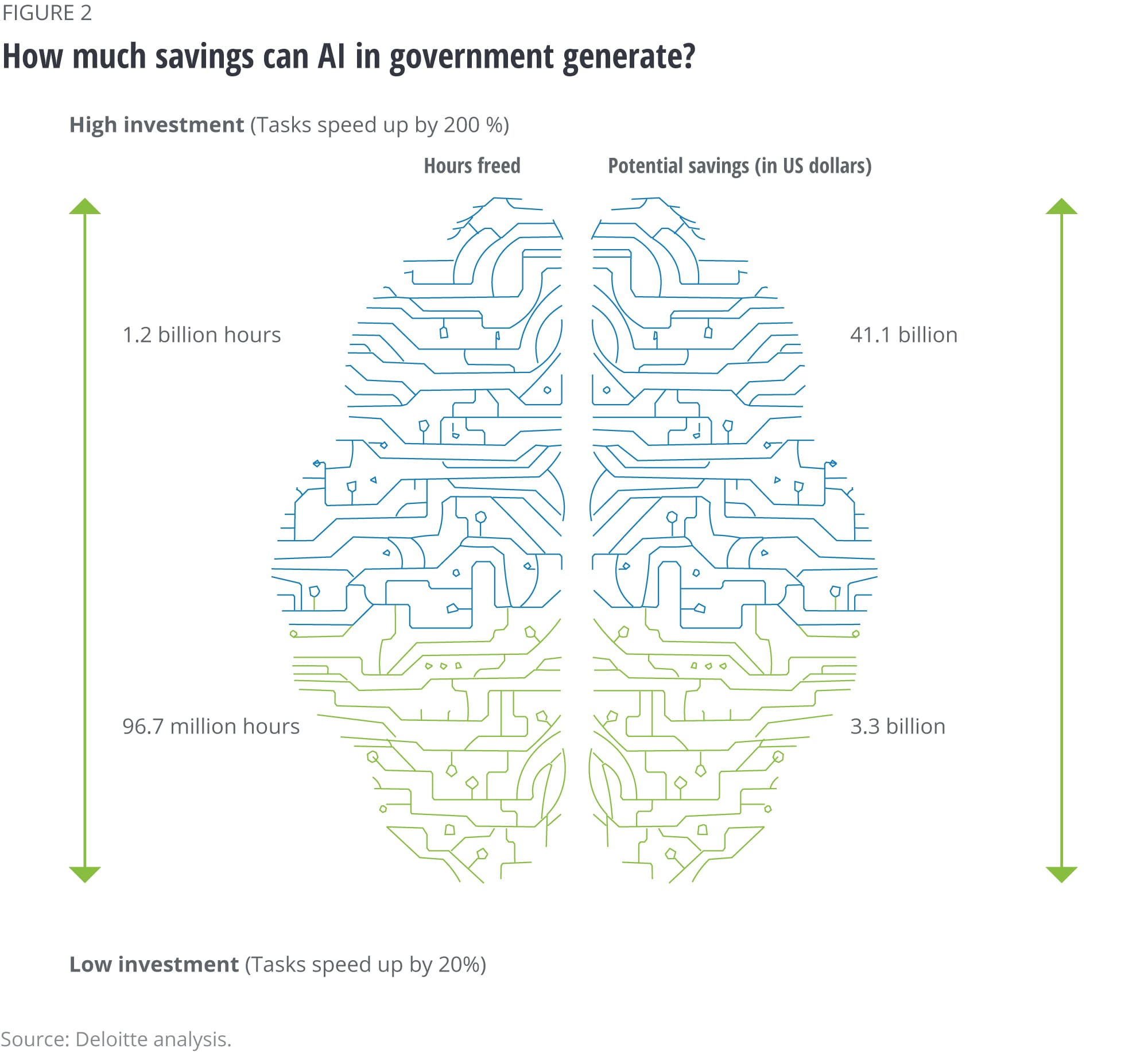

For the federal government, we estimate that high levels of investment in AI/automation could free up as much as 1.3 billion person-hours and save more than US$40 billion per year.7 Even modest application of RPA and AI could have a profound impact on government employee work (see figure 2).

When it comes to automation, agencies should consider their priorities. A cost strategy aims to reduce costs by using technology to replace employees, reducing headcount. A value strategy, on the other hand, focuses on increasing value by complementing human labor with technology or reassigning employees to higher-value work. For governments, a value strategy helps address the challenge of a workforce that often is not growing (due to age, retirement, and/or lack of budget) with growing citizen expectations.

How do you manage costs “smarter” in the future?

Many agency costs are the legacy results of past decisions. To make effective decisions regarding costs, leaders need up-to-date cost information. Otherwise, decision-makers will likely make choices based on some combination of out-of-date data, past precedent, and intuition based on past (and perhaps not applicable) experience. Next-generation data analytics tools can help leaders more effectively manage costs and tailor processes and services to both agency-specific challenges and evolving needs and conditions.

Governments manage three main categories of resources: people, physical assets, and money. Data analytics can help agencies make sense of operational data and turn it into usable insights to improve resource allocation in all three areas:

- Human capital is generally the most critical resource an agency manages, often exceeding one-third of the total budget. Data analytics can help agencies decide how to deploy staff to be most effective. For instance, Pennsylvania’s Bureau of Child Support Enforcement uses a “payment score calculator” to advise about caseworker outreach to noncustodial parents.8

- The second major category of resources includes equipment and physical assets, from weapons systems to field offices. Modern analytics tools help leaders make more objective decisions about deployment and investment in these assets. Data analytics leveraging connected sensors and real-time input from citizens, for example, can be used to optimize physical infrastructure and are a key part of what it takes to build a smart city. The SmartSantander project in Santander, Spain, uses this approach in real time to adjust energy use, the scheduling of trash pickups, and even how much water to sprinkle on the lawns of city parks.9

- The third critical resource government agencies manage is funding of outside organizations. This is handled through means such as grants, loans, and guarantees; the federal government distributes more than US$600 billion in grant funding each year. When awarding funding, the question of how government agencies should decide which organizations should receive grants is obviously crucial. One agency that is using data and data analytics to manage more than US$17 billion in grants is the United States Federal Railroad Administration (FRA),10 whose “enterprise data store” contains all relevant information on its high-speed rail grants and helps forecast the effect of investments on outcomes.

These are just tip-of-the-iceberg examples of the potential cost savings and mission enhancements government agencies can experience by using big data and data analytics strategically. But without the right technology infrastructure in place, government efforts to leverage data analytics and cognitive solutions may fail. Which brings us to the next important question.

How quickly can you move to and exploit the cloud?

IT costs are a major component of overall costs at the city, state, and federal level in most countries. The cloud offers agencies real cost-savings opportunities by converting what were large, upfront fixed investments (and subsequent maintenance costs) into lower operating costs that can flex capacity as demand requires. Despite these potential benefits, a 2017 Government Business Council and Deloitte survey of 328 senior government employees revealed only 24 percent of respondents believed cloud computing had a positive impact on their organization.11 Forty percent were unable to say if the cloud had any effect on their organization at all. So far, the pace of cloud computing’s rollout in government has been more of a marathon versus a sprint. What’s behind this slow adoption rate? Overall, the government has taken a “lift-and-shift” approach to implementation, allowing agencies to replicate in-house applications in the cloud without modifying their original design. This allows for a short-term cost savings, but it masks the potential impact the cloud can have on mission economics. Cloud computing’s real potential lies not in creating a cheaper version of today’s agency activities but in enabling new approaches to mission and costs.

Several agencies, including the US Department of Defense and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, are leading the government’s adoption of remote sensors as part of the rise of the Internet of Things (IoT).12 The IoT has the potential to transform agency economics as the flow of real-time data may make tasks such as periodic on-site inspections obsolete. But all that incoming data must be stored somewhere that it can be readily used—and the cloud fits the bill. Ensuring data accessibility in the cloud also sets the foundation for implementing the data analytics and cognitive solutions discussed above.

While the cloud enables next-generation cost management tools to work, next-generation tools also enable the cloud’s functionality. One of the most-cited barriers to cloud adoption in government has been security concerns.13 There is a recognized trade-off between security and access, an understanding that security requires more effort, more restrictions, less ease. Debate, when it arises, has often focused on how much convenience and access we are willing to forego in the interests of security. But tools such as risk modeling based on data analytics and biometric identification are reshaping the conventional security tradeoffs. These tools may simultaneously be powered by the cloud and make the cloud more secure.

How might you disrupt your agency’s business model?

The disruption in the commercial marketplace encompasses a whole new wave of business and service models; companies like Uber, Airbnb, and Amazon are reshaping entire industries. Blockchain has been suggested as the next technology that will enable disruption of industries in the near future.14 The effect of these digital technologies is so profound because they can reshape the relationship between economics and value that have shaped conventional patterns of operation. With the right set of next-generation tools, government agencies can redraw the relationship between resources and success by creating new models for organizing and pursuing their mission to deliver equal or better quality for less money. NESTA, a UK-based think tank, calls such an approach “radical efficiency,” the art of developing different and better models—not just lower-cost versions of existing ones.15

For example, Amazon and Netflix have built business models that deliver enhanced personalization and scale economies, breaking a historic tradeoff that insisted that low cost meant a one-size-fits-all solution for everyone. As a result, citizens now have higher customer expectations; they expect more personalized services without having to pay more to get them. As leading private sector companies have shown, these expectations can be met while preserving or increasing scale economies if they are fulfilled through next-generation digital tools. The US Army’s SGT STAR, for example, is an AI-based virtual assistant that answers recruiting questions. It does the work of 55 recruiters while using machine learning to tailor its responses to each potential recruit’s specific inquiries and concerns.

The most dramatic potential for personalized services at scale to reduce costs may be in health care. Telehealth, personal data monitors and remote sensing through the Internet of Things, and genetically tailored treatments could all fundamentally change the economics and experience of health services as we know them. It will take time for these technologies to come to fruition; perhaps they represent the “Third Act” in cost savings for some agencies. But what is exciting about these next-generation cost tools is that like cloud computing, they can offer cost savings today with the promise of more revolutionary cost savings tomorrow.

Structural cost management

The structural cost management approach takes a broad, integrated view of the organization and the larger ecosystem. While traditional cost management tools typically focus on individual cost categories or processes, structural cost management seeks to optimize an agency’s portfolio of activities using strategic choices and demand management. Its goals are to enhance operating models and build new service delivery models.

Structural cost management requires a deep understanding of cost accumulation. This means looking at what—and where—agencies are spending their money (appropriated, industrially, or working capital funded) and the degree to which those expenditures align with agency priorities. Going beyond simply targeting cuts to transforming agency economics also calls for leaders to analyze and understand what drives agency costs before they can explore potential structural cost management opportunities. Better data and analytical tools, new pressures, and recent success stories have all contributed to agency leadership’s continued interest in the structural cost management approach.

In the US federal government, we have seen an uptick in interest in structural cost management. This was prompted by the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which issued an executive order calling for agencies to examine if all of their activities were mission critical.16 The OMB followed up with guidance to help agencies evaluate if some of their activities would be better left to state or local governments, were redundant with other federal agencies, were too costly to justify their public benefits, or could be implemented more effectively and efficiently.17

Ireland has undertaken some of the most aggressive structural cost management efforts in recent years. Facing a massive budget deficit after the 2008 crash, the Irish government reduced the number of public agencies by 180, enacted a phased increase in the retirement age, and cut payroll by 3 percent.18 Cumulatively, these efforts reduced baseline spending by US$10 billion since 2008.19

Meanwhile, in Canada, the Strategic and Operating Review (SOR) under the Harper administration used a structural cost management approach to evaluate approximately US$80 billion of direct program spending. While its goal was to achieve US$4 billion in ongoing annual savings by 2014–2015, the exercise proved even more successful, reducing spending by US$5.2 billion.20

Once an agency leader casts aside the current structure of the organization and its activities, the number of possible options for change can be daunting. Below are a series of questions to help leaders identify significant opportunities for savings using structural cost management. To accomplish this goal, the questions also challenge conventional ways of doing business to enable exploration of truly different operating and delivery models.

What services can you share?

Structural cost management: Operating models and governance

Structural cost management approaches take a broader, more integrated view of the organization and the larger ecosystem. While this systems perspective opens up greater opportunities for savings, off-the-shelf solutions are less applicable and change can be more difficult to implement.

Sample methods and associated tools:

- Redesigning scope

- Shared services

- Core competences

- Portfolio optimization

- Influencing others

- Demand management

- Policies as cost drivers

Although shared services is not a new topic in government, so far, its deployment has been less extensive than it could be.21 Shared services in government goes beyond the benefits of consolidation within a single agency. For the last decade and a half, agencies have used shared services to source their mission support needs from a handful of other government agencies approved as service providers in particular areas, such as financial management, human capital, and acquisition. Motivated in part by the OMB executive order seeking innovation in cost management, agency leaders are now exploring a breadth of options for shared services.

Government seems ripe, in fact, for what we call service delivery transformation. This broad-scaled approach encourages integration of support services within and across agencies to achieve maximum economies of scale and other efficiencies while also expanding sourcing options to include alternative government and commercial providers and new models for service delivery and funding (including shared gains, for example). The goal of service delivery transformation is not simply to migrate services to a single large government provider; it is to find the best option for each service, wherever that option resides. When this type of transformation is successful, it frees up resources to improve outcomes and accountability for citizens.

In 2015, the US Department of Commerce (DOC) sought to streamline back-office service operations throughout the department’s 12 bureaus and the office of the secretary. To accomplish this, the DOC deviated from the traditional federal shared services path, which, for the last decade and a half, has had agencies source their mission-support needs from a handful of other agencies approved as service providers in particular areas such as financial management, human capital, and acquisition. The department instead developed a wider set of sourcing options; for each service it explored remaining in-house, moving to a third-party government operator, or shifting to a commercial provider.22 As a result, the DOC is expected to become the first cabinet-level department to adopt an enterprisewide combined service delivery model for all human resources, financial management, information technology (IT), and acquisition support systems.23

Just as the options for shared services have broadened, so have the reasons behind sharing. Cost and efficiency are only two of the benefits. A third important benefit is how it can affect key employees’ work responsibilities. From a human capital balance sheet perspective, utilizing more shared services models shifts the focus of employees away from their cost and toward the value they can create, or the return on human capital investment.24 When nonessential and/or less meaningful tasks can migrate to shared services, employees can devote more time to mission-critical work. In these ways, shared services can simultaneously cut costs and raise the value delivered by agency staff.

Why you?

The question, “What services can you share?” prompts government leaders to look for other organizations, government or commercial, that perform similar activities. The focus, historically, has been on back-room activities, which tend to be more common across large organizations. To date, leaders have been less likely to consider mission-focused activities as opportunities for migration to other providers. In our work, we are beginning to see greater interest in exploring alternative provider options for mission-focused work.

This reflects a pattern in the commercial world where firms identify their core competencies and then eschew noncore activities. Recently, we have seen government leaders perform this same analysis. To do this effectively, agency leaders should think of programs and activities not just in terms of the value they create; instead, they need to discern the added value their agency provides over other potential providers. This shifts the question from “Why do it?” to “Why you?”

This question requires government agencies to articulate what is distinctive about their own capabilities by exploring what would happen if a given program or activity were turned over to the next best alternative provider. Typically, this would involve comparing the value of keeping a program or activity versus eliminating it. But “gone” is not the proper default option. The activities in question might naturally be picked up by another organization, or might be intentionally migrated to another organization through an agreement, incentives, or a mandate. We have seen this, for example, in how the US Postal Service now handles passport applications.

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched ReImagine, a departmentwide effort to more effectively and efficiently fulfill its mission of improving the health and wellbeing of America’s population. As part of the initial transformation program design, over 150 HHS experts convened for an ideation session to identify priority challenges and potential solutions. During the brainstorming sessions, after a group prioritized around 25 top solutions from over 2,000 different concepts, the teams followed up by asking, “What role should HHS play, if any? Why?” They did this because they explicitly recognized that the best answer for which organization should handle an activity might be HHS, another federal agency, a state agency, an NGO, or even a commercial enterprise.

Investigating the “Why you?” question can be a nuanced exercise. A recent World Bank strategic planning effort looked at “the next best alternative provider” for the bank’s initiatives. Here, the next best option might mean a local development bank or commercial lender would assume a loan in a specific region. In another region, there might be no viable alternative to the World Bank due to unattractive loan- or region-specific risks or other issues. When a government organization examines its mission-related activities, such factors should be taken into account. To do this effectively, it may be necessary to unbundle a program or department, sending some activities to one place and some to another.

It is also important to think about finding a strong set of alternative providers. The OMB executive order mentioned earlier suggests agencies consider other agencies and state and local governments. Our discussions with federal government leaders have also included foreign governments, NGOs, citizen groups, industry associations, and private sector companies as possibilities. Of course, there may not be any viable alternatives, which brings us to our next question.

What is the right portfolio for your organization?

Commercial enterprises evaluating their portfolio of activities may discontinue products and services if revenues do not cover costs. This has been a major path to cost savings when firms employ structural cost management. It is not just the structure of the organization but also the structure of its portfolio of products and services that drives costs. The OMB executive order asks, “whether the costs of continuing to operate an agency, a component, or a program are justified by the public benefits it provides.”25 It is a worthwhile question, although in our experience working with government leaders, most government programs pass this test, and in many cases existing legislation would make jettisoning a line of activities impermissible. Perhaps a better question would then be, “Could the same resources have greater benefit for the mission if deployed differently?”

Answering this question is a major goal of evidence-based funding. A recent report from the Pew Charitable Trusts and the MacArthur Foundation defines evidence-based policymaking as “the systematic use of findings from program evaluations and outcome analyses (‘evidence’) to guide government policy and funding decisions.” The Pew-MacArthur report found that “most states have taken some evidence-based policymaking actions in at least one human service policy area” but that “advanced application is less common.”26 At the federal level, evidence-based policymaking has increased over the last decade27 but the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking created by congress and the president in 2016 noted, “Greater use of existing data is now possible in conjunction with stronger privacy and legal protections, as well as increased transparency and accountability.”28

Evidence-based policymaking may require, among other things, restructuring an agency’s portfolio of activities, and their related costs, by shifting funds to activities that yield better mission-related returns per dollar. While not a new concept, as data becomes ubiquitous and the cost of data analytics continues to fall, implementation has become more feasible.

Oregon, for example, is using data to advance more evidence-based programs and services. The state targets many of its grants to local public safety agencies to test strategies that reduce prison recidivism and save prison costs. In human services, Oregon’s Pay for Prevention initiative directs funds to evidence-based interventions; its goal is to prevent children and youth from entering the state’s child welfare and foster care systems in the first place, which would ultimately save tax dollars.29

How do you get people to accept lower-cost approaches?

Oregon’s experience using evidence-based policymaking illustrates how a state can optimize its portfolio, eliminating grants when less effective in favor of higher-return alternatives. However, changing an agency’s portfolio of services is not always so straightforward. For example, a government agency could realize significant cost savings, while also improving outcomes, if citizens would take advantage of the least expensive channels for meeting their needs. Shifting those still using paper to digital channels is probably the most widespread example. The CEO of a commercial firm can simply choose not to serve customers who want to use a costly channel. But a government agency has less discretion about its “customers;” typically, it cannot simply cut them off. It can, however, nudge them toward alternatives, which would result in a changing agency portfolio over time.

Nudging as a toolset grew out of the fields of behavioral economics and behavioral science. Eschewing traditional “carrots and sticks” motivational techniques, nudging restructures how choices are presented and communicated in order to influence people’s decision-making.30 Nudges gained attention with the 2008 publication of Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, in which the authors wrote: “Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.”

While nudges were not developed as a cost-saving measure, they have proven to help government leaders reshape portfolios to lower costs. In the United Kingdom, for example, nudges have helped shift citizens seeking renewals for disability parking away from filling out paper forms to using less-costly online renewals.31 Nudging has also been shown to reduce costs by encouraging compliance for agencies like the IRS and New Mexico’s Department of Workforce Solutions.32 And, importantly, nudges are being incorporated into next-generation cost management approaches to encourage employees to adopt and use new protocols.

Bonus: What policy decisions are your biggest cost drivers?33

As noted above, government agencies do not have the same flexibility as firms do, in part because they need to conform to governmentwide and/or agency-specific policies. For this reason, we add a fifth “bonus” question that looks directly at potential costly structural constraints imposed by policy. Policy choices can be a sensitive part of any government cost-reduction program; any proposed change is likely to be widely scrutinized. But structural cost savings can be found in policy stipulations. It is possible that by relieving particular policy constraints, agencies can then adopt lower-cost approaches without negatively impacting core services.

In speaking about the HHS ReImagine initiative’s human resources (HR) efforts, Christine Major, HHS deputy assistant secretary for human resources at the time, observed, “We’re continually asked to do more, do better, do faster [and] do cheaper, but at the end of the day, we’re still tied to a lot of the rules and regulations that haven’t changed.”34 HHS ReImagine seeks to, among other things, modernize HR systems to enable a higher-performing 21st-century workforce. As part of that effort, a small internal team is looking into possible changes it can make to current HR statutes and regulations, and ideas it could bring to congress.

Policy choices, in some cases, are rooted in long-ago decisions; they established rules, procedures, and processes appropriate for the time, but some may no longer be necessary due to social or technological changes. Does it really make sense to publish certain public notices in the newspaper in the Internet age? Should federal meat inspectors be required to look at each carcass or should they instead be deployed based on health risk? Does having a different license plate for each county in a state justify the costs of managing multiple inventories? For that matter, is having a service office in every county the best use of scarce resources?

Reexamining existing policies can also reveal current practices that may needlessly inconvenience citizens. What is really gained by requiring documents to be notarized? Why can’t someone simply take a photo of their latest utility bill and email it in, rather than dealing with the hassle of finding an envelope and stamp to mail in a paper copy?

While some policy changes may require legislation, others could be accomplished through executive action. In some cases, there will be good reasons for continuing current practice, but it never hurts to ask the questions. Leadership drives policy choices, and cost-saving directives can often help leaders think about policies through a different lens.

Traditional cost management

Traditional cost management approaches typically disaggregate the enterprise into discrete pieces such as a cost category or a particular process or purchased commodity. Proven methods and tools are then applied to drive out costs by improving productivity, leveraging scale, eliminating waste, and so on. Continuous incremental improvement then allows for future gains.

Compared to the structural or next-generation approaches, the traditional approach has the advantage of a well-proven track record and, in some cases, off-the-shelf solutions. But by focusing on individual elements, the tools and supporting methods have a more limited impact on the organization’s overall economics. This approach includes methods and tools that are focused on internally driven costs and others that deal with external spending (see sidebar, “Traditional cost management: Cost categories and processes”).

Traditional cost management: Cost categories and processes

Traditional cost management approaches typically disaggregate the enterprise into discrete pieces; for example, a cost category, a particular process, or a purchased commodity.

Sample methods and associated tools:

- Internally focused cost levers

- Consolidation and standardization

- Process reengineering

- Quality management and continuous improvement

- Real (physical) asset management

- External spending reduction levers

- Indirect and direct sourcing efficiencies

- Acquisition reform

- More effective supply chain integration

While many of the methods and tools associated with the traditional cost management approach will be familiar to government leaders, they have often been deployed in a tactical, narrow, and/or localized manner. When combined with next-generation and structural approaches, however, traditional cost tools can have a more transformative impact. To achieve this, government leaders should consider the following questions for their organizations.

How can you better exploit economies of scale?

The public sector often fails to leverage its size to realize significant economies of scale. Activities are often duplicated across functions, departments, or geographies within an agency, leading to potentially higher costs. Overall size does not automatically equate to scale economies; government leaders need to understand and take advantage of the specific factors that drive scale effects. If there are site-specific overhead costs, such as administrative functions, geographic consolidation can yield savings. If task specialization can lead to higher productivity and learning, for example, in an office that provides a variety of services to a variety of citizens, consolidating work assignments may boost productivity and reduce costs. If the return on technology investment depends on utilization, for example, having automated testing equipment for a regulatory agency, then consolidating activities can help make the business case for modernization.

Today’s scale-related opportunities, however, are not just about consolidation. In our discussions with agency leaders over the last year, we heard how splitting activities across functions can hamper efficiency, but we also heard how it can impede learning and opportunities for innovation. Across many agencies, different parts of the organization interact with the same clientele and other stakeholders, albeit in different ways. The scale effect that leaders seem most excited about today—that has the potential to be truly transformative—integrates the scope of the organization, exploiting scale in ways that enable experiences and information to be shared across the agency to gain new insights that enhance mission success and improve customer service. The US HHS’s ReImagine initiative is intended to better enable HHS to respond to current challenges in health care and in public assistance programs, and to align to the president’s management agenda. At its launch in 2017, HHS executives noted that while integrating IT across its organizational silos could eliminate IT redundancies and improve operational efficiency, even greater benefits could be gained by making data more transparent and shareable across the department’s agencies. This insight should make it possible not only to eliminate duplicative efforts across multiple agencies but also to bring new insights, solutions to, and early identification of (and coordinated, departmentwide responses to) emerging problems such as the opioid epidemic. This model of bringing together disparate data sources across the department, including relevant external sources, has already been tested during the Opioid Code-a-thon held in December 2017, with HHS and external teams coming up with innovative technology prototypes to address challenges around prevention, care, and treatment.

Does your current footprint make sense?

An enterprise’s physical footprint—its buildings and lands in various locations—is related to economies of scale and has been a typical focus in traditional cost management. Today, government organizations are taking a hard look at the assets that make up their current footprints. Both direct facilities costs and the additional costs associated with them (such as local management) represent significant expenditures. Every two years, the GAO releases its High Risk List of federal programs and operations that are especially vulnerable to waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement, or that need transformative change. The 2017 List once again includes “real property management,” as it has since 2003. The cost management opportunity is significant, with more than 250,000 owned or leased buildings and billions of dollars spent on operation and maintenance.35

Current physical configurations reflect past decisions, demographics, and needs. More importantly, they reflect historical tradeoffs among service delivery, costs, and physical proximity. Technology has fundamentally changed these tradeoffs. Thus, we find foreign ministries today, for example, completely rethinking the locations, staffing, and equipping of their embassies to reflect contemporary conditions, needs, and possibilities. States and cities have comparable asset management issues, albeit at a smaller scale, and over the years, they have explored both sales and sale-leaseback of properties.36 Significant savings may be found by asking and evaluating: What work should be done where? and Do we need all these facilities in light of today’s technologies, real estate markets, labor pools, and costs?

In 2016, the US government created new laws to help address real-property cost opportunities: the Federal Assets Sale and Transfer Act of 2016, the Property Management Reform Acts of 2016, and updated versions of the General Services Administration’s suite of Real Property Asset Management Tools.37 Together, these laws and tools encourage and enable individual agencies to find near-term savings by consolidating buildings, which reduces maintenance and operating costs. But to get real traction and improvements in real estate property management, government leaders may need to get more serious about allowing agencies to keep a significant portion of the funds generated when a property is sold and to reinvest some of those funds back into their portfolios.

What reforms can you make to acquisitions?

The acquisitions process, an area long targeted for reform, represents another typical focus of the traditional cost management approach. The US federal government spends more than US$300 billion on common goods and services every year,38 so even small percentage efficiency gains translate into significant savings.

The 2018 President’s Management Agenda (PMA) calls for a renewed effort in category management—leveraging common contracts and best practices to drive savings and efficiencies. Its goal is to achieve US$18 billion in annual savings from category management. Historically, many agencies purchase the same goods or services through individual contracts; this results in significant variations in pricing, lost opportunities for volume discounts, and hundreds of duplicative contracts.

Now, opportunities are emerging in acquisition reform to help meet this challenge. New providers and provider models (such as Amazon’s) along with new tools can offer greater visibility and responsiveness and lower cost in global supply chains by:

- Taking advantage of technology that now allows for centralized acquisitions systems for economies of scale and decentralized purchasing for quick response;

- Transforming the fundamental acquisitions model and mindset through, for example, Agile software development,39 which can enable lower cost and more nimble development and implementation; and

- Integrating the supply chain not just to reduce waste but also to improve speed, agility, quality, cost, service, and innovation by enabling a seamless flow of both materials and information. When combined with next-generation technologies, integrated supply chains can become digital supply networks40 as discussed in table 2.

What new tools can you use to cut waste, fraud, and abuse?

Any successful attempt to eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse is the equivalent of found money—money that could be spent delivering real value and improving program effectiveness. Consistent with traditional cost management tools like quality management and reengineering, this means taking a broader and more holistic approach. It also requires leaders to recognize, as cost of quality studies have shown, that an ounce of prevention can be worth many pounds of cure. While next-generation cost tools offer new opportunities (discussed below), agencies can achieve significant savings by taking a more holistic and prevention-focused approach to waste, fraud, and abuse using current technologies. Tennessee’s Medicaid program TennCare, for example, enforced statewide sharing of suspected fraudulent provider lists by making simple changes in policy, procedure, and technology—saving the state US$50 million in one year, according to TennCare’s former director.41

This broader view can include customers or their equivalent. Customer tools, like mapping the customer journey, segmentation, human-centered design, and understanding drivers of choice, were originally developed to enable growth for commercial firms. More recently, government organizations have applied these tools to a variety of target groups. While they are not usually cost-focused in this context, using them along with traditional cost tools can yield additional cost savings and/or improvements in program implementation and target group outcomes (e.g., citizen satisfaction).

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) has used human-centered design principles to identify potential improvements in system economics. The BOP mapped the experience of an individual moving from prison to a residential reentry center (RRC), or “halfway house.”42 This study led to proposed changes in procedures, such as working with eligible inmates to secure identification documentation prior to RRC transfer.43 The hope is that such efforts can reduce recidivism and lower the societal cost of incarceration.44

In summary, the traditional cost approach still has a great deal to offer government agencies in terms of savings in areas like those described here. Savings can be found within the agency, upstream with suppliers and purchases, and downstream with customers and their experiences. Traditional cost tools can have greater impact when they focus on new areas and more holistic solutions. But even when applied holistically, there are limits to what can be achieved within the current structure.

Conclusion: Looking across the three approaches

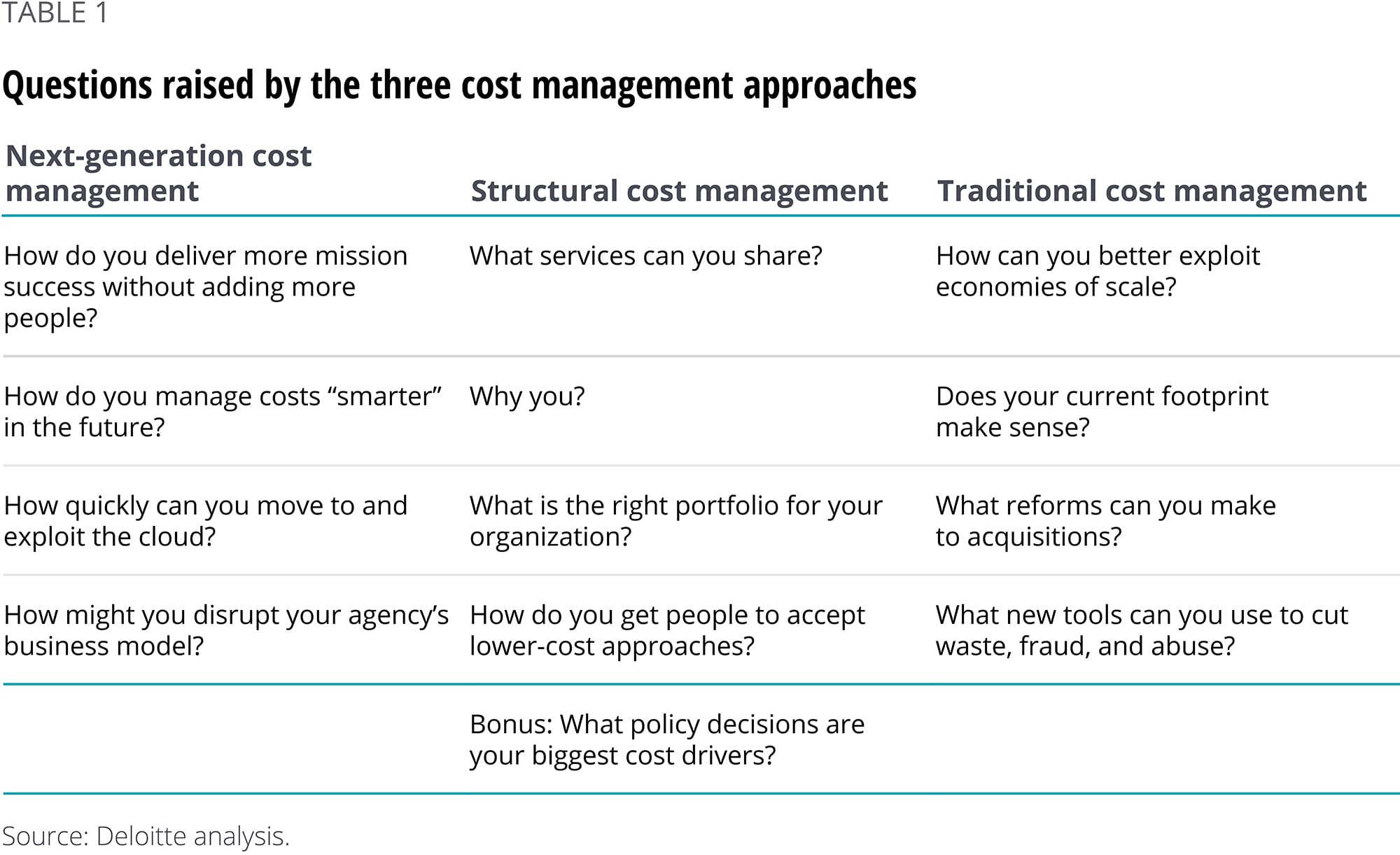

These three cost management approaches—next-generation, structural, and traditional—are different but not mutually exclusive. They differ in the tools used and in the maturity of those tools. They differ in the questions they raise when exploring opportunities (table 1). They differ in terms of a leader’s familiarity with and her or his degree of implementation certainty and control. This last difference warrants more discussion.

An individual team can manage implementation of traditional cost management tools given their limited scope. The organizational owner of a single process, operating unit, or activity can create cost savings by using familiar, traditional tools and approaches within their own piece of the organization—though we encourage leaders to think more broadly.

The structural cost management approach, by definition, cannot be accomplished within the existing boundaries and rules of current organizations. Its power comes from redrawing those lines. Therefore, leaders should first consider what can be improved within the framework of existing laws and regulations that would add the most value, and which approaches would first require congressional or other stakeholder approvals before proceeding.

Finally, the next-generation cost management approach could be applied narrowly within the existing structure, for example, by using AI to augment or automate a single activity. Or the digital tools could be used to create a new, innovative channel through which citizens might engage across an agency, in real time, such as through phone apps. In either case, the biggest difference with the next-generation approach is that it comes with a degree of uncertainty and ambiguity. These are emerging innovations. Leveraging their capabilities to transform agency economics will require elements of both implementation and discovery.

Private sector experience has shown the three approaches can be deployed effectively in concert. Acquisition and supply chain provides a useful illustration. Significant gains can be achieved by deploying any one approach on its own. But structural integration of first-, second-, and third-tier suppliers is tremendously simplified when agencies use traditional cost management’s category management function to reduce the number of contracts and suppliers.

Similarly, while the real-time data tools and analytics of next-generation cost management would benefit any supply chain, their value is dramatically enhanced when all parties involved have been selected for their willingness to share and respond to information. As this rationalized, integrated, data-enhanced set of suppliers and buyers uses real-time information flowing across the network, buyers can predict when delays may occur and how their actions may affect capacity and timing; meanwhile upstream, clearer windows into real-time demand allow suppliers to be more proactive.

Finally, when additional digital tools like additive manufacturing and IoT data from products in the field are incorporated, the system no longer behaves like a series of links in a chain but as a digital supply network.45 By moving across all three cost management approaches, governments can achieve a lower cost, highly efficient, agile, and responsive flow of materials coupled with a high-velocity, continuous flow of information and analytics.

Given the breadth and scope of tools from all three cost management approaches and how they can be applied, government agencies have a tremendous opportunity to stage an Act Two in cost management. Employing the three approaches in a complementary manner can not only help to transform an agency’s economics, but also improve mission delivery and services to citizens and businesses.