The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Building recovery on a foundation of trust

21 minute read

22 April 2020

Resilient leaders shift organizational mindsets, navigate uncertainties, and invest in building trust in order to develop a recovery playbook that serves as a solid foundation for the post-COVID future.

Resilience is a way of being

Whereas organizations used to describe agile change as “fixing the plane while it flies,” the COVID-19 pandemic has rewritten the rules of upheaval in modern times. Those of us leading any organization—from corporations to institutions to our own families—are not fixing the plane in midair, we’re building it. Times like these need leaders who are resilient in the face of such dramatic uncertainties.

Learn more

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Explore more resources for resilient leaders

Connect with our COVID-19 client PMO for help at covidclientpmo@deloitte.com

This article is featured in Deloitte Review, issue 27

Download the issue

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

The first article in this series described the essential foundations leaders need in order to effectively navigate through the crisis.1 Resilient leaders are defined first by five essential qualities of who they are, and then by what they do across three critical time frames: Respond, Recover, and Thrive.

As we progress into the Recover phase of the crisis, resilient leaders recognize and reinforce critical shifts from a “today” to a “tomorrow” mindset for their teams. They perceive how major COVID-19-related market and societal shifts have caused substantial uncertainties that need to be navigated—and seized as an opportunity to grow and change. Amid these uncertainties, resilient leadership requires even greater followership, which must be nurtured and catalyzed by building greater trust. And resilient leaders start by anticipating what success looks like at the end of recovery—how their business will thrive in the long term—and then guide their teams to develop an outcomes-based set of agile sprints to get there.

Resilience is not a destination; it is a way of being. A “resilient organization” is not one that is simply able to return to where it left off before the crisis. Rather, the truly resilient organization is one that has transformed, having built the attitudes, beliefs, agility, and structures into its DNA that enable it to not just recover to where it was, but catapult forward—quickly.

The mindset shift: From today to tomorrow

“The historic challenge for leaders is to manage the crisis while building the future.”—Henry Kissinger2

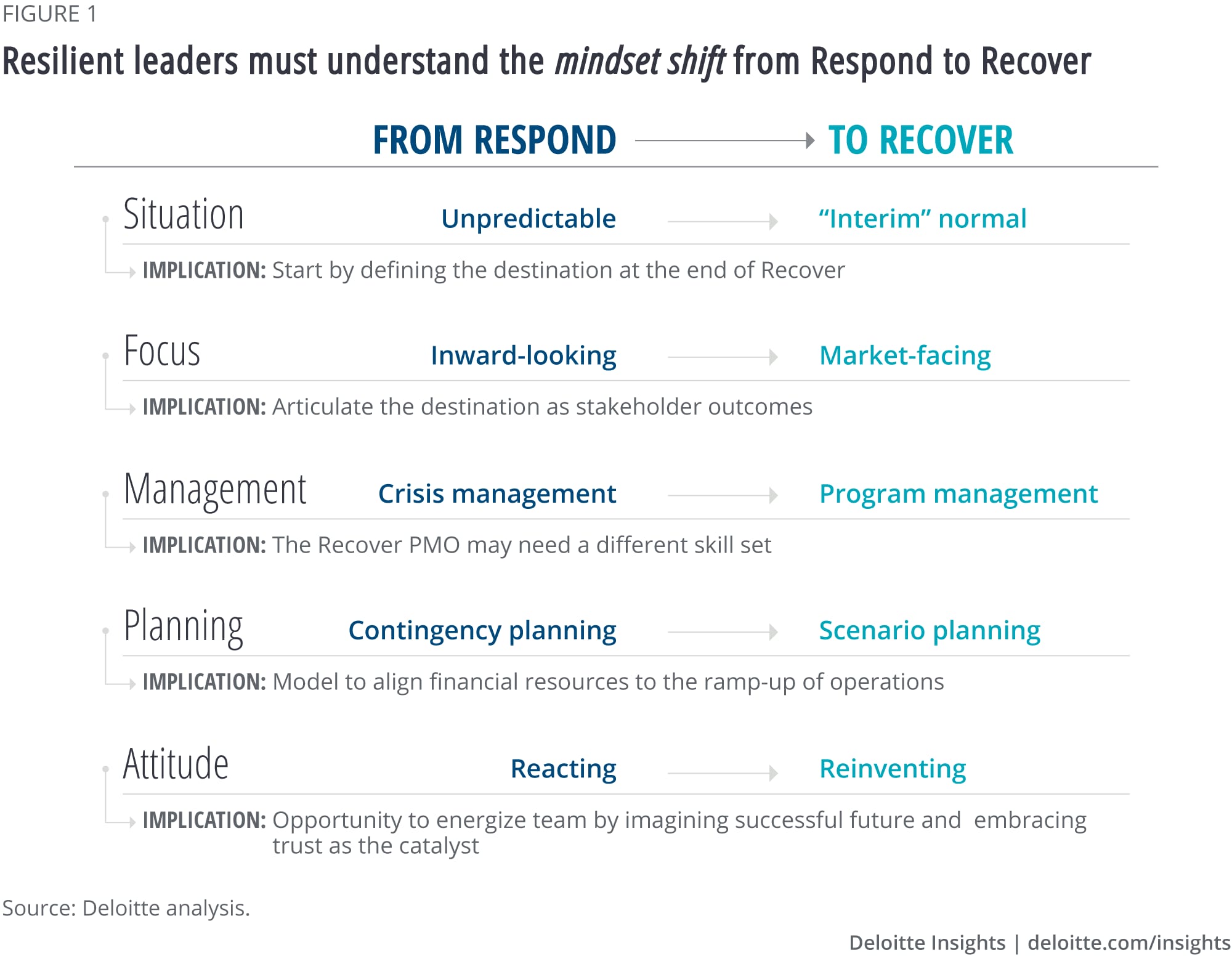

For many of us as leaders in the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, the days started to blend together. In fact, some have said that the COVID-19 world has only three days in the week: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. In that spirit, resilient leaders need to shift the mindset of their teams from “today” to “tomorrow,” which involves several changes that have important implications for the path to recovery. Specifically, as shown in figure 1:

- The situation shifts from the unpredictability and frenetic activity of the early Respond period to a more settled, though still uncomfortable, sense of uncertainty (an “interim” normal). The implication: The situation invites leaders to envision the destination at the end of Recover.

- The focus of leadership expands from a very inward (and entirely appropriate) focus on employee safety and operational continuity to also include embracing a return to a market-facing posture. The implication: Leaders should envision the destination in terms of desired stakeholder outcomes, not internal processes.

- Management goals shift from managing the crisis—keeping the organization functioning—to managing the transition back to a restored future. The implication: The Recover project management office may need a different skill set than the Respond project management office.

- Planning shifts from short-term contingency planning to mid- and long-term economic and scenario planning to understand the related impacts on operations, employees, financing, and so forth. The implication: It is critical to model the alignment of financial resources to the cash required to ramp-up operations.

- Leadership attitude shifts from a primarily reactive mode to anticipating how to reinvent the organization. The implication: Leaders should seize the opportunity to energize their teams by imagining a successful future and embracing trust as the catalyst to get there.

The only certainty is … uncertainty

“The recovery from the COVID-19 crisis must lead to a different economy.”—António Guterres, ninth Secretary-General of the United Nations3

The substantial shifts in society, its institutions, and its individuals during the crisis have introduced major uncertainties into our familiar structures. Assumptions about what is true and stable—for example, the freedom to move unrestricted in free societies—have been upended. These shifts have resulted in macro-level changes in and uncertainties about the underpinnings of business and society that resilient leaders must navigate:

Changes in the social contract. Societal expectations of corporations are being reframed to ensure the viability of all stakeholders. The implicit contract between businesses and their stakeholders has always been based on accepted—and generally unspoken—assumptions about “the way things are.” But the way things are has changed, and that contract is being rewritten. For example, in the implicit “future of work” contract, remote work may be both more productive for the organization and more desirable for employees. Further, there are new considerations around work/life balance, job fluidity, and employee well-being gaining prominence in ways that suggest these factors are reshaping a new standard for how, where, and when we work.

Changes in the roles and rules of institutions. As the crisis unfolds, we find business doing government (such as by instituting employee stay-at-home orders before local authorities) and government doing business (such as by providing material financial support in exchange for equity), while nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other agencies are doing both (such as the World Health Organization shipping more than 2 million units of personal protective equipment to 133 countries).4 Concurrently, public-private partnerships (such as the U.S. National Institutes of Health teaming with American and European government agencies and over a dozen biopharmaceutical companies to coordinate an international research response to the pandemic5) herald a new form of cooperation that blurs traditional public/private boundaries, and may presage greater collaboration between government and business.

Unpredictability in financing sources and uses and in capital markets. The pandemic has sent financial shock waves through economies, sectors, governments, financial institutions, treasurer’s offices, restaurants, nonprofits, and purses. The sources and uses of cash and the movement of liquidity during the crisis have been unpredictable. Leaders will need to plan for wide variations in their financial position and needs, all of which are dependent on the disease’s progression, the level of government stimulus, and the pace of economic recovery.6 They will also need to evaluate their ability to handle a potential mounting debt burden and the impact this will have on government and financial institutions.

Permanence of customer behavior changes. The crisis has already had a profound impact on customer behavior. As China’s markets reopened, a segment of consumers who visited physical stores was reluctant to touch anything.7 Consumer research by Nielsen asserts that, after the crisis, people’s daily routines will be altered by a new cautiousness about health,8 suggesting that some shifts in behavior could be long-term. The significant increase in home deliveries has even increased the influence on behavior of an emerging player in the value chain: the independent delivery company. Leaders will need to anticipate whether and how the pandemic has permanently altered behaviors, experiences, expectations, and the role of digital engagement.

Expectations for physical, emotional, financial, and digital safety. Recovery will create anxiety among stakeholders as the post-COVID world takes shape. Understanding the fears that stakeholders are grappling with—and how their expectations for safety and security have changed, perhaps permanently—will be critical for leaders as they seek to restore confidence and chart a new path forward. It remains to be seen how the four “epidemics” researchers have identified—COVID-19 itself, fear of the virus, fear about the economy, and even fear of the ultimate vaccine—will ultimately be resolved.9

“To get the world back on track requires controlling all four horsemen of the COVID-19 apocalypse—which makes the response far more complicated.”—Joshua Epstein, professor of epidemiology, New York University School of Global Public Health10

Each of these shifts represents a significant area of uncertainty for leaders as the world heads toward a new and yet-to-be-defined equilibrium. Amid the uncharted waters of the COVID-19 crisis, leaders should expect a significant increase in the number of “unknown unknowns”11—or at least a precipitous contraction of confidence in what we once knew to be true. We have gone from a world of widely agreed-upon absolutes to a relative world where our feet are firmly planted in midair.

Yet we also see new business models emerging amid these uncertainties. An e-commerce supplier in Asia-Pacific opened up its logistics capabilities to third parties;12 a major telecom company transitioned a large scale tech transformation to 100 percent virtual delivery;13 the strategic partners of a technology firm stood up a temporary finance function within days to provide critical services despite a pandemic-imposed hiring freeze;14 and dozens of hospitals in China opened online fever clinics via a digital platform to meet the exponential growth in demand for online health consultations.15

Trust as a catalyst of recovery

During the Recover phase, resilient leaders need to inspire their teams to navigate through these significant COVID-related uncertainties. But great leadership requires even greater followership—and followership is nurtured by trust. Indeed, many leaders have built a significant bank of trust from deftly navigating through the early frenzied unpredictable stages of the crisis.

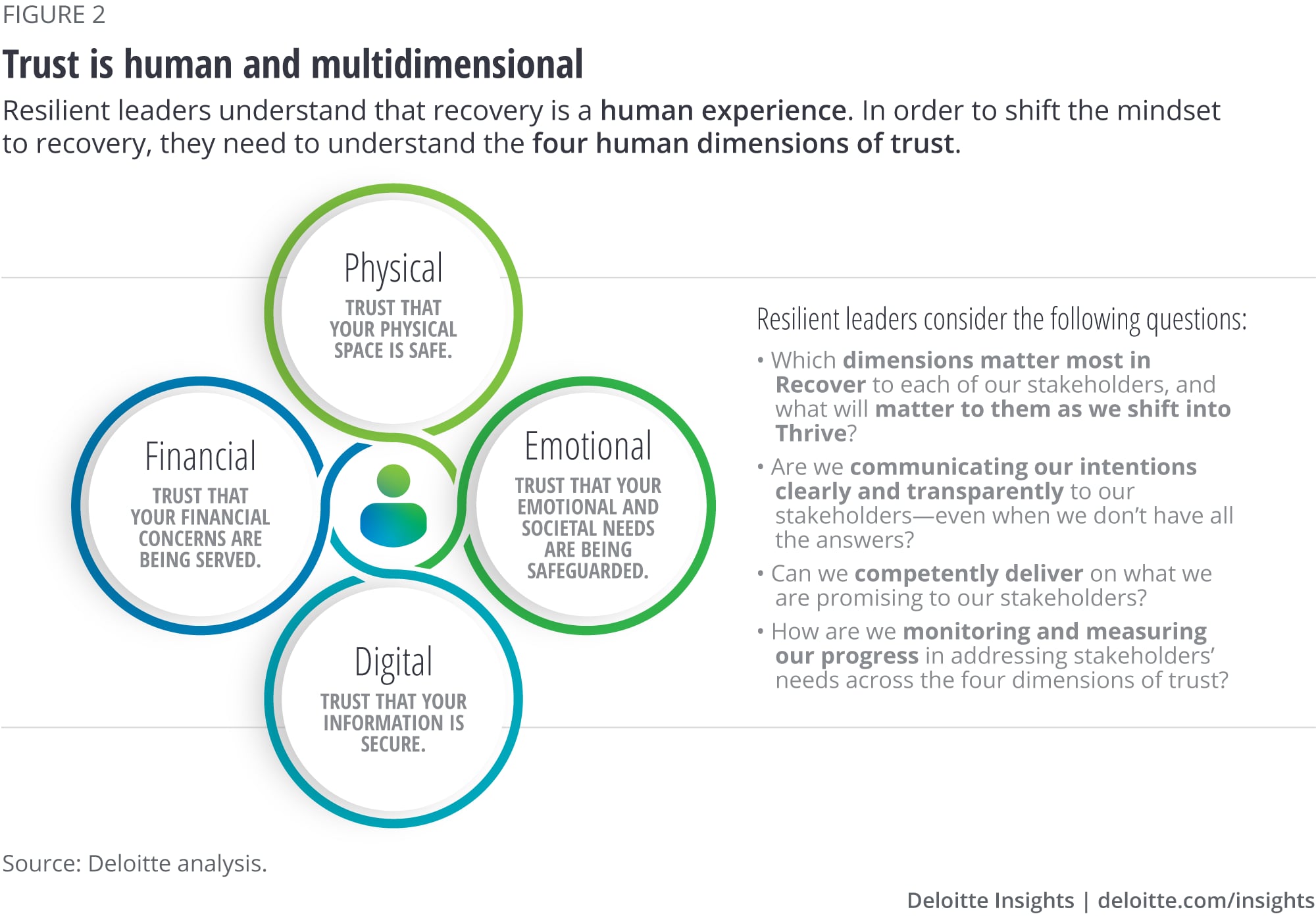

Although some may think of trust as an abstract, ethereal concept, it is, in fact, a quite tangible foundation that is essential to successfully reaffirming a strong relationship with stakeholders through the recovery. Two attributes of trust are particularly relevant in this regard.

First, trust is a tangible exchange of value. It has no value in isolation, but represents value only in an interaction with others—for example, customers, suppliers, employees, investors, and team members. Likewise, trust is only built in relationships, where a real, genuine give-and-take provides mutual value. Trust is also accretive: Invested wisely and prudently, it grows through repeated affirming experiences; when invested poorly, it rapidly depreciates. Further, research demonstrates that trust also yields results such as economic growth and shareholder value,16 increased innovation,17 greater community stability,18 and better health outcomes.19

Second, trust is actionable, and human, along multiple dimensions. Trust is nurtured and built among stakeholders along four different dimensions: physical, emotional, financial, and digital (figure 2). And trust starts at the human, interpersonal level. COVID-19 has heightened stakeholder sensitivity across these four dimensions, which offers greater opportunities to act to build—or lose—trust. For example, trust may be built among employees when leaders thoughtfully consider how to reengage the workforce in the office (such as by reconfiguring the space to honor social distancing), or when they go to great lengths to preserve as many jobs as possible rather than just preserving profits. Similarly, trust may be built among customers when organizations add extra security measures to protect customer data from cyber threats.

Author Stephen Covey summed up the trust calculus well: “Trust is the glue of life. It’s the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It’s the foundational principle that holds all relationships.”20 And social impact investor Andy Crouch highlights the interplay between trust and an organization’s recovery efforts: “In order to find our way to the new playbook for the mission and people that have been entrusted to us, we will need to act at every moment in ways that build on, and build up, trust.”21

Anticipate the destination

A recovery of this scale and scope hasn’t been accomplished in most of our lifetimes, and it is complicated by the complexity of simultaneously navigating rapidly changing governmental mandates, fragile supply networks, nervous team members, and cautious customers.

Given the market uncertainties, companies that try to recover by relying on conventional wisdom may discover that the world they thought they knew is no longer there when they arrive. The way in which leaders created plans and playbooks in the past may no longer be relevant, especially if those plans and playbooks focus on either a functional or internal view. Organizations that are successful in the Recover phase must make clear choices about where, how, and when they want to emerge using these four moves:

- Define the destination. Envision what being wildly successful looks like at the end of recovery, and determine what immediate steps can be taken to move quickly and decisively toward it.

- Anticipate outcomes. Ensure that the path to success is defined by stakeholder-focused outcomes rather than internally focused functional processes.

- Run sprints. Use agile principles to navigate the range of uncertainties—beyond just epidemiological factors—that the organization must traverse in the journey from its current state to the destination.

- Judge your timing. Carefully sense when it is appropriate to pivot to Recover.

Imagine, for instance, the retail unit of a major telecom company. The destination at the end of recovery might include reopening 50 percent of its retail stores, shifting 50 percent of its customer renewal activity to being Web-based, and consolidating repair activities into central hubs in metropolitan areas. Its recovery playbook would detail the path to desired outcomes for customers (such as a new, touchless store experience, enhanced online ordering, and the establishment of repair hubs); employees (such as reopening stores and retraining workers for new needed skills); and suppliers (such as replenishing the supply chain to match demand estimates)—with provisions for adjusting those plans as the company learns more about consumer behavior, market needs, and competitive threats.

Define the destination

Defining the destination first and then working backward is an approach that can help leaders create more aggressive and creative plans. Envisioning the leadership team in a position of success is emotionally enabling, and it frees the team from some of the constraints of the present. It also disrupts incremental thinking, which often hampers creativity.

Identifying immediate quick wins to move rapidly and decisively toward the destination is important. Many companies find that the crisis has dissolved bureaucratic boundaries, making decision-making more streamlined and action more responsive to accelerate outcomes.

Leaders will need to ask key strategic questions when defining the destination (for instance, “What is most important in creating advantage: strategy, structure, or size?”). The answers can suggest a variety of tactics to pursue during recovery, such as accelerating implementation of pre-COVID-19 strategic options, scaling pilots in progress, birthing new organic businesses, and even finding deal opportunities among distressed companies and brands.

A recovery lab can be an excellent way for senior leadership teams to explore these strategic questions. The tangible outcome of such a lab is a recovery playbook that has been codesigned (and therefore owned) by the entire senior management team. Beyond the playbook itself, the intangible benefit of doing this is that it encourages the senior team to mesh around a common goal, purpose, and set of outcomes.

Since the recovery project management office (RPMO) needs to be chartered, leaders should also consider whether they have the right team for this phase’s remit. This could be a great time to tilt the composition of the COVID-19 response team to include more operational expertise, recruiting team members with more execution-based skills and expertise. Also, given the added complexity of various stimulus programs and local regulations, the RPMO may have an elevated role in supporting functions such as legal and tax. Reporting within the RPMO should include a balance of internal operating metrics and external indicators that can provide real-time insight into macro recovery indicators. Organizations may need to invest in new data sources in the short term to provide required information about the pace of recovery.

Finally, modeling the financial impact of the recovery playbook is a critical check and balance. Does the plan hold up under various economic scenarios? Does the organization’s projected liquidity enable it to rebuild operations and working capital commensurate with the plan?

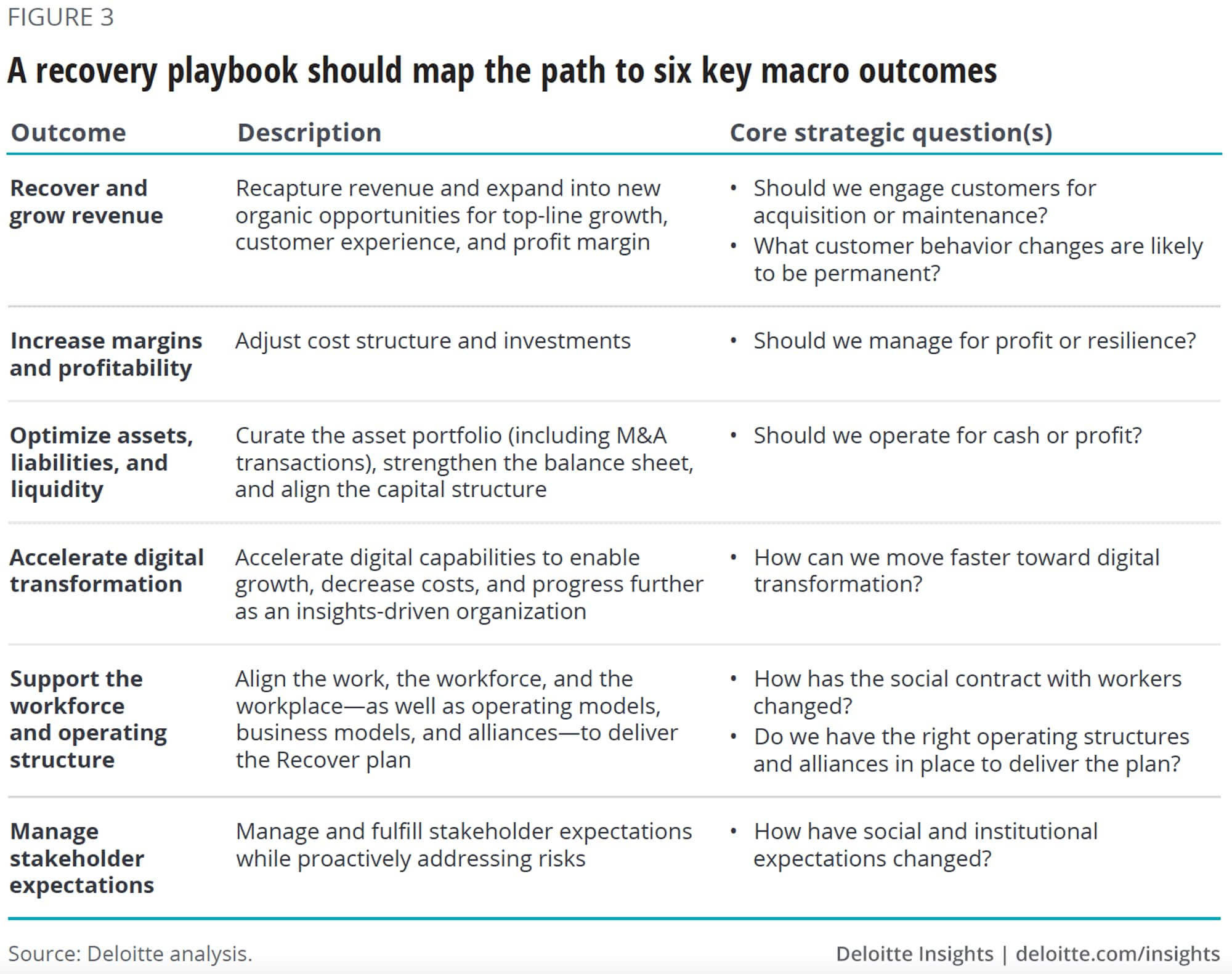

Anticipate outcomes

We have identified six key macro outcomes that a recovery playbook should address (figure 3), and several core strategic questions for the C-suite to consider in setting scope and direction for the recovery plan.

In the first article of this series, we specified six priority functional areas to be addressed during the Respond phase: Command Center, Workforce and Strategy, Business Continuity and Financing, Supply Chain, Customer Engagement, and Digital Enablement. A functional focus was entirely appropriate in the immediacy of the Respond phase. However, as noted above, the shift from Respond to Recover requires a mindset pivot from an internal, functional view to the outcomes-based view described here.

See the appendix to this article for more detail on what the C-suite should consider when developing the recovery playbook.

Run sprints

Agile delivery principles are essential on the Recover journey. Not only might the destination shift as new issues emerge, but “unknown unknowns” can cause unexpected detours. Running the Recover program in short (such as six-week) sprints enables leadership and the RPMO to monitor the program and make mid-course corrections.

In the Respond phase, organizations around the globe demonstrated a remarkable agility to change business models literally overnight—implementing remote work arrangements, offshoring entire business processes to less-affected geographies, and collaborating with other organizations to redeploy furloughed employees across sectors. In each situation, the urgency of getting results trumped typical bureaucratic orthodoxies. Resilient leaders will harness those experiences to embed rapid, agile decision-making into the culture throughout the Recover phase, doing away with traditionally cautious, silo-based mindsets.

“The shift has happened in days, not months. Businesses may be able to learn how to move faster, acting in more agile ways, as a result.”—Amy C. Edmondson, Harvard Business School22

Judge your timing

One of the core questions many companies are already asking is, “When should we pivot to Recover?” But the boundary between Respond and Recover is blended rather than a bright line. Due to the pervasive, far-reaching medical and economic variables, there is no simple, mathematical answer to the question. Effective sensing and AI mechanisms can be critical inputs to augment what is still a qualitative decision of when, where, and how to restart.

The right time to activate the recovery plan will vary across geographies and sectors, and even among different companies in the same geography and sector. Regions where the infection rate has subsided will be more able to sustain activation than regions where the disease is still spreading. Sectors that have suffered a lesser impact, such as media or technology, may shift to recovery much earlier than heavily affected sectors such as transportation or leisure. And each company will have its own operating nuances: Those with widely dispersed back-office support centers or better visibility up the supply chain, for instance, may be able to begin recovery efforts sooner than those that do not.

Leaders weighing when to pivot to recovery also must consider startup lead times. For instance, a retailer may be able to reopen in days, while some process manufacturing industries may require months for a shuttered plant to be recalibrated to required tolerances.

What’s normal … next?

As organizations emerge from Recover and transition into the Thrive phase, trust, coupled with the five qualities of resilient leadership, serves as a strong foundation on which resilient leaders can build the business models to address the new markets that will emerge.

What might life be like after the crisis passes, and what will it take to thrive in a world remade? In a collaboration between Deloitte US and Salesforce, some of the world's best-known scenario planners developed four distinct scenarios that consider the potential future societal and business impacts of the pandemic (see sidebar, “The world remade by COVID-19: Scenarios for resilient leaders”).23 The team explored possible disease progressions and severity, the level of collaboration within and between countries, the health care system response, the economic consequences, and social cohesion in response to the crisis. The four scenarios provide a view of the future three to five years from now, created through a structured process to stretch leaders’ thinking, challenge conventional wisdom, and drive better decisions today.

The world remade by COVID-19: Scenarios for resilient leaders

The passing storm. The pandemic is managed due to effective responses from governments to contain the virus, but it has lasting repercussions that disproportionately affect small and medium businesses as well as lower- and middle-income individuals and communities.

Good company. Governments around the world struggle to handle the crisis alone, with large companies stepping up as a key part of the solution accompanied by an accelerating trend toward “stakeholder capitalism.”

Sunrise in the east. China and other East Asian nations are more effective in managing the virus and take the reins as primary powers on the world stage.

Lone wolf. A prolonged pandemic period spurs governments to adopt isolationist policies, shorten supply chains, and increase surveillance.

Sociologists have observed that history does not move linearly, but rather in cycles punctuated by a crisis approximately every 80 years.24 Such generational cycles have been found in Old Testament, Homeric, and Islamic cultures, and have been proposed by prophetic archetypes such as Lao-Tzu and Buddha. Researchers have identified seven such cycles in Anglo-American history since the mid-15th century, with the last crisis being World War II … 80 years ago:

Each time, the change came with scant warning … Then sudden sparks ... transformed the public mood, swiftly and permanently. Over the next two decades or so, society convulsed. Emergencies required massive sacrifices from a citizenry that responded by putting community ahead of self. Leaders led, and people trusted them [emphasis added]. As a new social contract was created, people overcame challenges once thought insurmountable—and used the crisis to elevate themselves and their nation to a higher plane of civilization. … [It] is history’s great discontinuity. It ends one epoch and begins another.25

As resilient leaders embarking on recovery, we embrace trust as the essence of resilient leadership. Invest it wisely and it will yield extraordinary returns.

Appendix: C-suite considerations for the recovery playbook

Recover and grow revenue

Strategic questions

- Should we engage customers for acquisition or maintenance?

- What customer behavior changes are likely to be permanent?

Key considerations

- With the shutdown of the past several months, the organization should determine if customer behaviors and brand preferences have moved or changed. While many organizations may assume that they can message customers as they did pre-crisis, there may be a need to market new features of products and services to remain relevant and win back share.

- Because many customers have sampled new service delivery models, from virtual health care to home grocery delivery, it is possible that they have rapidly adopted what they perceive as safer and more convenient models of interacting with brands.

- The crisis likely created the opportunity for innovation to create new products, services, or markets by designing around constraints. Companies may find opportunities for cross-industry collaborations that did not exist before the crisis.

Increase margins and profitability

Strategic question

- Should we manage for profit or resilience?

Key considerations

- Most value chains pre-crisis were optimizing for operating efficiencies. The crisis revealed unexpected implications of this approach, such as that auto production could be held up by a single part that was no longer available in an affected area. Leaders should define where on the profit versus resilience spectrum they want their organization to sit across all operating categories.

- For example, given the uneven pace at which recovery is expected across industries and geographies, it is likely to be more important to enable sufficient flexibility, as well as visibility upstream and downstream, in the supply chain than to make tactical changes to the flow of goods.26 While the organization lays the groundwork for alternate supply chain arrangements based on geographic and business resilience considerations, trends around concentration of supply may naturally reverse themselves to provide for future flexibility.

- As organizations incorporate customer demand expectations and patterns into supply chain planning, understanding customer demand signals based on data rather than intuition will be critical. The crisis may have exposed deficiencies in the availability and reliability of the data required to make meaningful decisions.

Optimize assets, liabilities, and liquidity

Strategic question

- Should we operate for cash or profit?

Key considerations

- Alignment of key lending and investor stakeholders on terms, timing, and capital availability is critical in this phase. Reorienting these stakeholders around cash generation versus profit generation may require some resetting of expectations.

- Assuming that the organization has taken steps to bolster its overall liquidity in the Respond phase, the critical consideration is the sufficiency of liquidity to fund operations during recovery across multiple economic cases over the next 18 to 24 months.27 The more detailed the modeling around these cases, the better, given the large number of unprecedented factors (such as stimulus payments, local regulatory edicts, and so on) that could potentially impact cash flow.

- Tapping into the myriad of government assistance programs is also important in supporting this outcome.28

- The possible entrance of different classes of investors into the market (such as venture funds, sovereign wealth funds, and vulture investors) has the potential to place added stress on the organization as it executes its recovery plan. Staying alert to these external forces and leveraging the board for counsel and advice will remain critical to ward off this threat.

Accelerate digital transformation

Strategic question

- How can we move faster toward digital transformation?

Key considerations

- At many organizations, the pace of digital transformation reached hyperspeed as a result of the crisis. While many were already taking an agile approach to digital transformation, the crisis likely exposed deficiencies and forced organizations to move faster. The crisis may have also unearthed some opportunities to pursue competitive advantage as well.

- In the Recover phase, leaders should prioritize the most important digital investments and potentially rethink the technical architecture. Just as with supply networks, the ability to draw on an extended network of digital solutions may provide a more resilient infrastructure and allow the organization to focus on its most strategic applications.

- The ultimate challenge may be around funding the investments needed to drive digital enablement. With the pace of change accelerating in technology, putting the organization on a path to constant and ever-growing investment in digital will prove challenging.

Support the workforce and operating structure

Strategic questions

- How has the social contract with workers changed?

- Do we have the right operating structures and alliances in place to deliver the plan?

Key considerations

- Social distancing and other new practices and regulations have dictated changes in work, the workforce, and the workplace—the most prominent being the widespread shift to remote work. A big consideration is whether certain of these changes should become permanent. In some instances, for example, productivity may have increased as more tools to virtualize the workforce came into use.

- Once decisions have been made around where and how work will be done, several tactical decisions will be required, such as:

- Whether employees should return all at once or on a phased basis over time

- How the organization will ensure worker safety and well-being as the business recovers

- Now is also the time to determine whether offshore and/or outsourced capabilities are sufficiently diversified or whether they need to be reconsidered. The anticipated uneven reopening of markets and geographies will add an unusual amount of complexity to this analysis.

Manage stakeholder expectations

Strategic question

- How have social and institutional expectations changed?

Key considerations

- Boards have become acutely aware of their responsibilities, and also of their contributions to the financial, physical, emotional, and digital well-being of management, employees, investors, and other stakeholders.29

- Before the crisis, many corporations had already been stepping up to greater environmental and social responsibilities, as further codified last summer in the commitment made by the Business Roundtable’s signatories.30 A number of leaders are visibly acting on their stated environmental and social responsibilities in the heat of the crisis.31 Senior leaders should set expectations for the range and measurement of their organizations’ ongoing environmental and social responsibility efforts as they embark on the critical Recover phase—for their companies and for our globe.

Explore our COVID-19 content

-

Connecting for a resilient world From Deloitte.com

-

United States Economic Forecast Q3 2024 Article1 month ago

-

Potential implications of COVID-19 for the insurance sector Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the investment management industry Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 potential implications for the banking and capital markets sector Article4 years ago

-

The economic impact of COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) Article4 years ago