South Africa Laying the foundations for recovery

8 minute read

13 March 2020

Policymakers have little wiggle room left to stimulate demand, and need to continue their focus on rolling out structural reforms to revive the economy.

The South African economy has been under severe pressure, lagging many emerging markets and most of its African peers. Just in the past decade, unemployment has steadily increased from already high levels, economic growth has weakened and public finances have deteriorated substantially. The fragile domestic environment is further exacerbated by slower-than-anticipated global growth. Given South Africa’s limited resources, structural reforms are vital in unlocking the economy’s growth potential, and the pace of reform implementation needs to increase.

Learn more

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

An uncertain global climate

The global climate and its recovery are uncertain, and many downside risks persist. In early February, Standard and Poor’s1 already downgraded China’s growth expectation largely due to the recent coronavirus outbreak. According to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) January 2020 World Economic Outlook (WEO) update, emerging markets will likely underperform, dragging down global growth.2 Global growth is estimated at only 2.9 per cent in 2019 (down from 3 per cent in the October 2019 WEO update), and forecast at 3.3 per cent for 2020 (down from 3.4 per cent) and 3.4 per cent for 2021 (down from 3.6 per cent). The full impact of the COVID-19 outbreak however is still being estimated and it is not unforeseeable that further downward adjustments will be made to growth forecasts. The worse-than-expected global projections are contributing to sub-Saharan Africa’s (SSA), including South Africa’s, woes.

Not all is lost – economic growth for SSA is expected to remain moderate, albeit slower than initially projected, estimated at 3.3 per cent for 2019 and forecast at 3.5 per cent for 2020 and 2021. By comparison, emerging and developing economies are forecast to grow better, at 4.4 per cent in 2020 and 4.6 pe cent in 2021.3 Nevertheless, the African Continental Free Trade Area (commonly known as AfCFTA) agreement has increased confidence for future growth.4 In particular, only this past decade, countries such as Ethiopia, Ghana and Rwanda have doubled their economies in size, growing as much as 7 per cent or more on average.

However, some of the regional economic powerhouses in SSA are struggling. Weak oil prices, alongside the need for economic reforms, have adversely affected Africa’s largest economy, Nigeria. Severe drought conditions in Kenya have weighed down growth.5 South Africa’s economy is also struggling, with high unemployment, weak economic growth and excessive public debt.

The stressed South African economy

South Africa’s macroeconomic performance has been marred with structural rigidities, political instability, policy uncertainty, underperforming state-owned enterprises (SOEs), drought and unpredictable electricity supply. Together, these have been a significant drag on business and consumer confidence – business confidence dropped to its lowest in 20 years in 3Q19,6 while in 4Q19, consumer confidence fell to its lowest since 4Q17.7 In fact, the current business downcycle has been the longest since 1945.8

Similarly, gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP – often seen as a proxy for investing in a country's future – has been on a downward trend, reaching 18.2 per cent in 2018 (down from the 2008 high of 23.5 per cent) and estimated to have declined further in 2019.9 The unemployment rate increased to levels last seen during the 2008 global financial crisis, registering a high of 29.1 per cent in 2019.10 Meanwhile, inflation remains subdued. In the most recent monetary policy statement, inflation is expected to average 4.1 per cent for 2019; the policy rate was decreased by 25 basis points, with the reserve bank highlighting the urgent need for structural reforms.11 However, the economic deterioration, alongside an ever-increasing public debt, leaves little wiggle room for fiscal support. Unfortunately, this, in turn, limits inclusive growth and support for the vulnerable, which are critical for a country as unequal as South Africa.

The low-growth rut

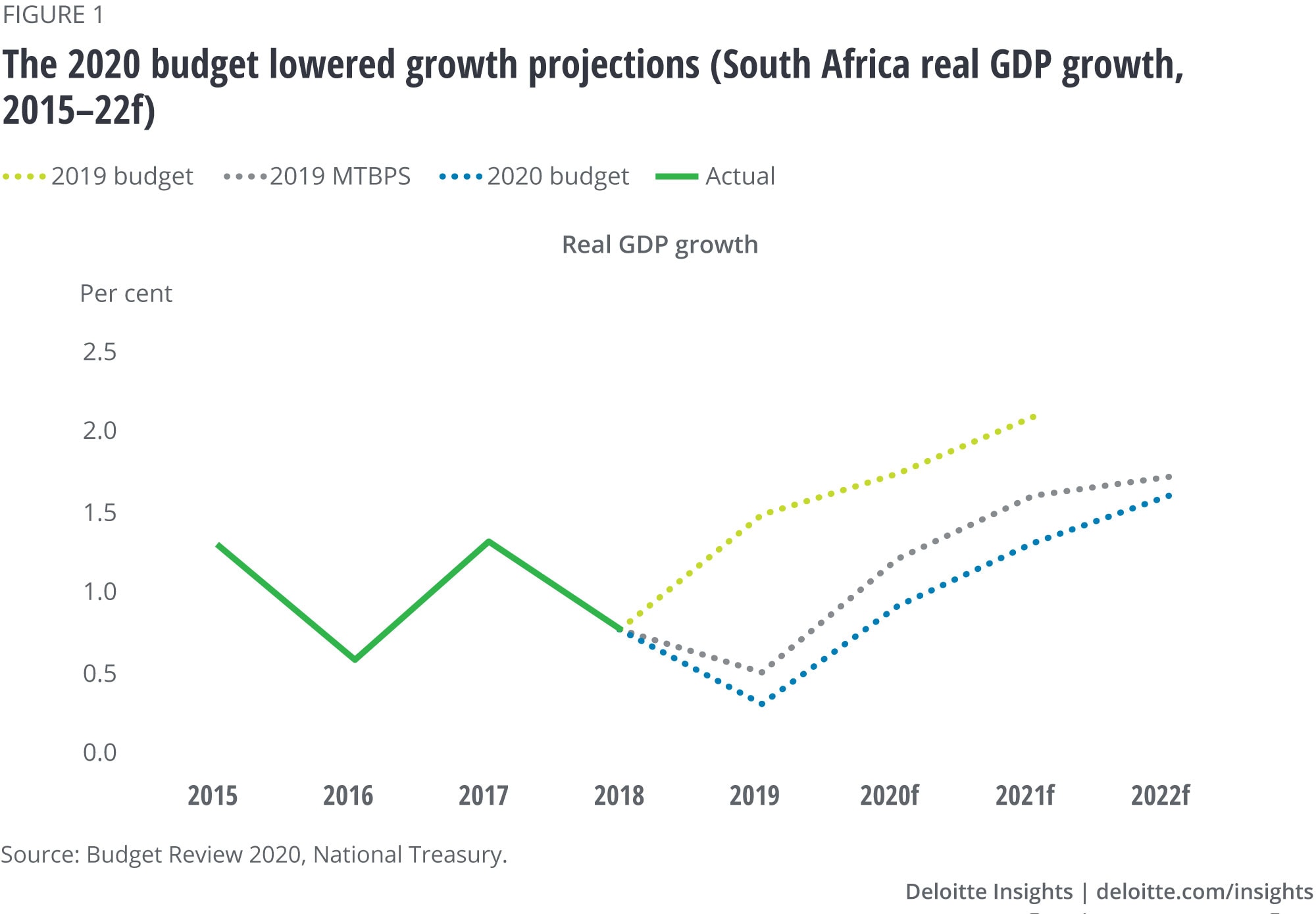

Growth remains persistently sluggish, with the 2020 budget read in February 2020 yet again lowering GDP growth projections (figure 1).12 GDP growth is estimated at only 0.3 per cent for 2019 (down from an expected 0.5 per cent in the 2019 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement or MTBPS). Data released by Statistics South Africa in March 2020 lowered the 2019 estimate to 0.2 per cent, with the country slipping into a technical recession in 2019 (two consecutive quarters of negative quarter-on-quarter growth).13

Medium-term growth forecasts remain around 1 per cent, at 0.9 per cent for 2020 (down from 1.2 per cent), 1.3 per cent for 2021 (down from 1.6 per cent) and 1.6 per cent for 2022 (down from 1.7 per cent), according to the 2020 budget. The slower estimates are partly attributed to the ongoing electricity supply woes. Additionally, persisting structural impediments that are eroding competitiveness and productivity, policy inertia that is slowing reform implementation, more electricity shortfalls and financially weak SOEs together with the potentially adverse impact of COVID-19 on a small open economy like South Africa, pose some of the greatest risks to the country’s economic recovery.14

The effect of the weak economic environment is far-reaching and deep – the IMF recently highlighted that GDP per capita growth has, in reality, been negative for the past five years,15 effectively making South Africans poorer over this period. This will continue to be the case over the next three years.16

The rising debt burden

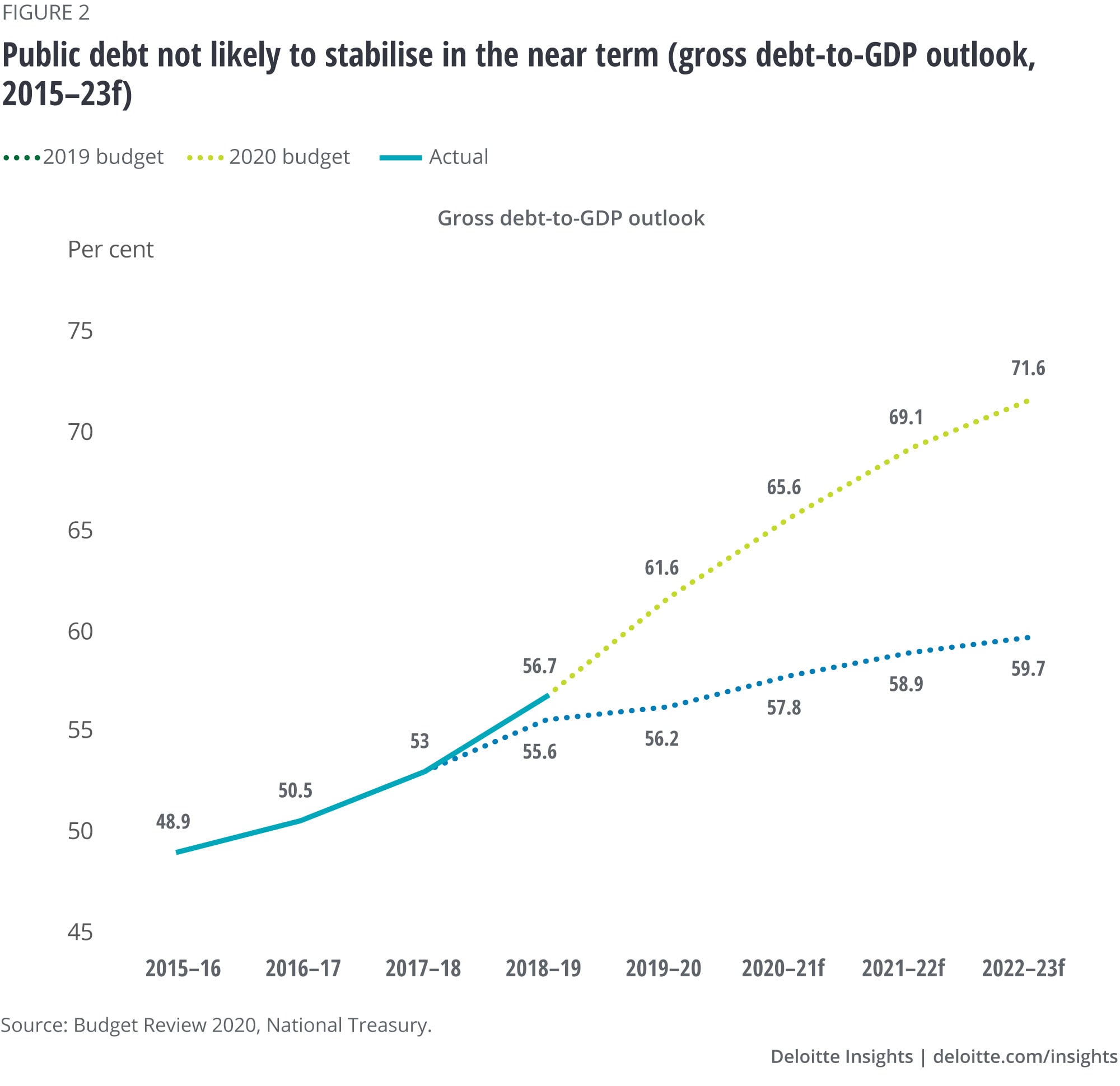

The enduring low growth has led to lower-than-expected individual, corporate and value-added tax collections, worsening already weak public finances. The consolidated budget deficit is expected to widen further from 6.3 per cent of GDP in 2019–20 to 6.8 per cent in 2020–21, narrowing to 5.7 per cent in 2022–23.17 The outlook for the gross debt-to-GDP ratio has deteriorated significantly since the 2019 budget where it narrowly exceeded 60 per cent before stabilising. The latest estimates, as already hinted towards in the 2019 MTBPS read in October last year, point to public debt not stabilising in the medium term (figure 2). The gross debt-to-GDP ratio is now estimated at 61.6 per cent for 2019–20 and projected to reach 71.6 per cent in 2022–23, substantially exceeding the 60 per cent threshold.18 Kick-starting growth, boosting revenue collection, changing the composition of expenditure and reforming SOEs will be required to stabilise the ballooning public debt burden.

Additionally, debt-service costs have increased and are now the fastest-growing expenditure item for the government. These are expected to grow by 12.3 per cent over 2020–21 to 2022–23. In comparison, health is expected to grow 5.1 per cent and economic development 6.6 per cent.19 Growing debt-service costs, lacklustre growth and financially weak SOEs have added a significant strain to the fiscus, and the sheer size of these interest costs could potentially crowd-out social and economic spending, such as education, health and social grants.

On the path to economic recovery?

The downside risks to the domestic economy and the fiscus remain substantial, the biggest being unreliable power supply and multiple financially weak SOEs. Restructuring of the electricity sector, with ZAR230 billion allocated over the coming decade towards this end, will be important to create a stable and secure source of energy supply to households and businesses alike.20 SOEs – budgeted to receive a further ZAR129 billion over the medium term – will still need to explore sustainable plans to improve governance and operations alongside stabilising their finances.21

Given South Africa’s economic and fiscal deterioration, widely expected tax increases were not tabled in the budget. The Finance Minister recognised that the already-small tax base and stressed business environment could not have endured further tax increases. The budget provided some tax relief for individual taxpayers, and signalled the possibility of reducing corporate income tax rates in future in line with international trends. On the expenditure side, proposed measures to stabilise finances include trimming the public sector wage bill, reducing wasteful spending and shifting the composition of expenditure from consumption to investment, particularly to infrastructure development.

While some commentators felt that the budget speech was mainly to appease ratings agencies and avoid South Africa from losing its last remaining investment-grade rating, the reality is that little resources are available to tackle major economic obstacles. Urgent structural reforms are critical to revive the South African economy.

The National Treasury has emphasised the need for economic reforms previously. For instance, a number of short-, medium- and longer-term interventions were proposed in a Treasury-published policy paper, 22 while the 2019 MTBPS highlighted that some of these reforms could be implemented using minimal state resources.23

The 2020 budget also focused on the need and urgency for structural reforms, especially for building business confidence and stimulating private sector investment.24 Part of the government’s economic reform agenda thus includes lowering the cost of doing business through modernising network industries, preferential measures for small businesses, and restructuring SOEs and inviting private sector participation into sectors such as electricity generation. It also includes implementing the ‘reimagined’ industrial strategy through developing master plans that will boost investment, exports and employment in prioritised sectors.

As reforms need time to gain more momentum, many might furthermore might not have an immediate impact on GDP growth, given a lag in the associated benefits. They do, however, have the potential to unlock higher and job-creating growth opportunities in years to come. Immediate reforms could thus create fertile ground for critical longer-term reforms.25 For example, by lowering the high barriers to entry for businesses, the government can foster competition as well as inclusion, supporting both fiscal sustainability and inclusive economic growth.

Nonetheless, necessary reforms have been difficult to implement and require political will. And while South Africa has the foundations in place for an economic recovery, it is running out of options. Stepping up structural reforms is crucial, with trade-offs only becoming more difficult the longer such reforms are postponed.

More from the Economics collection

-

Eurozone economic outlook, September 2024 Article2 months ago

-

A view from London Article5 days ago

-

Monetary policy in emerging economies Article5 years ago

-

Monetary policy in advanced economies Article5 years ago

-

Russia: Political news overshadows economic performance Article6 years ago