Retirees of the future: Increased worries about income security and growing inequality Issues by the Numbers, August 2019

11 minute read

09 August 2019

Pension funds of major economies are stressed for resources in the face of aging populations and falling birthrates. Policy fixes exist, but some of the most popular will further increase income inequality among retirees. Ensuring retiree income-security is a tightrope walk for governments and current and future retirees alike.

It is not only the workforce of the future that presents challenges to business and policy leaders. With more of the current workforce contemplating their postwork future with increasing trepidation, policy changes by the private and the public sector are critical … and this must happen sooner rather than later.

Learn more

View the related infographic

Explore the Issues by the Numbers collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

Advances in health care, education and nutrition, declining birthrates, and a growing proportion of older adults have put the world economies in uncharted territory—of planning for retiree benefits. With fewer people entering the workforce, the exit of the older adults from the workforce is creating stress in many government retirement plans, particularly in those where retirement payments are funded by current workers (the pay-as-you-go systems). Some of these plans will potentially be in a fund deficit—where taxes coming in will be insufficient to make full and timely payments—in the near term. In other words, the retirement plans will be bankrupt—unless something changes.

Governments have a tough task on hand as there is more than what meets the eye. Although most governments are encouraging businesses to help ensure a financially secure retirement for their workers and are urging citizens to save for their own retirement income security, the reality is that most people depend on national plans for retirement income-security. However, national plans are stressed for funds and to shore up funds, they are pushing governments to increase retirement ages of workers. This worsens the hardships already borne by lower income workers and exacerbates the already increasing income inequality, even in retirement.

To illustrate the precariousness of the situation faced by a growing number of countries, we examine the national pension plans for six countries: The United States, China, Japan, India, Brazil, and the Netherlands.

The current state of affairs

The combined public and private retirement systems of the countries examined in this article cover a wide range of combinations of adequacy and sustainability.1 India ranks low on both factors, providing inadequate benefits and falling into the unsustainable range. Brazil ranks high in adequacy of benefits but ranks even lower than India on the sustainability scale. Japan’s pension system ranks slightly higher than Brazil’s in terms of sustainability, but below average in the adequacy of its benefits. China’s pension is equal to Japan’s in terms of benefits and somewhat higher in terms of sustainability. The United States has slightly higher sustainability and adequacy ranks, but it is the Netherlands that compares very well not only with this group but with the entire group of 34 countries that Mercer included in its study—second only to Denmark.2

As the cornerstone of most retiree security-systems is the public component, we focus our discussion on public financing schemes. For example, in the 24 countries from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for which data is available, private pension spending averaged 1.5 percent of GDP in 2013, equal to just 20 percent of the average public spending on retirement benefits.3 A description of the pension plan designs of the countries discussed in this article is shown in figure 1. These countries, with the exception of India, rely on a pay-as-you-go system (payments made by or on behalf of current workers flow to current retirees as a set or defined benefit) and coverage is universal or near universal. In India, workers get the payout from their individual accounts at age 58. The full retirement age for the more standard pension plans ranges from 50 years to 66 years. Benefit formulae generally factor in wages and years of work, and most programs are financed by a combination of employer and employee contributions, with some countries also including general transfers from the government.

Another important measure of retiree benefits is the replacement rate. Only India has a flat replacement rate of 87.4 percent across income classes, and while it looks impressive, it is not actually as useful as one might believe because a mere 12 percent of the population is covered by the plan (figure 2). The other five countries have progressive replacement rates, i.e., although high earners will receive higher-value pension amounts, lower earners receive a higher proportion of their prior earnings than their better-paid peers. Of these countries, only the Netherlands has mandatory private plans. With both private and public plans, the country has a flatter distribution of replacement rates, albeit rates in all three earnings groups are almost 100 percent.

Rough going ahead

While policymakers can debate as to what portion of retirement income governments should have responsibility for, what is not in debate is that all these programs will face challenges due to aging populations. Although Japan has the most severe imbalance between the size of the working population and the retiree population, all the six economies we are discussing are aging. Even Brazil and India, with their relatively younger populations, will likely face severe demographic headwinds in the future. In the next five years, the ratio of people aged 65 and older to working age population will average just under 30 percent for the OECD countries, but for all these economies that ratio rises rapidly after that (figure 3).

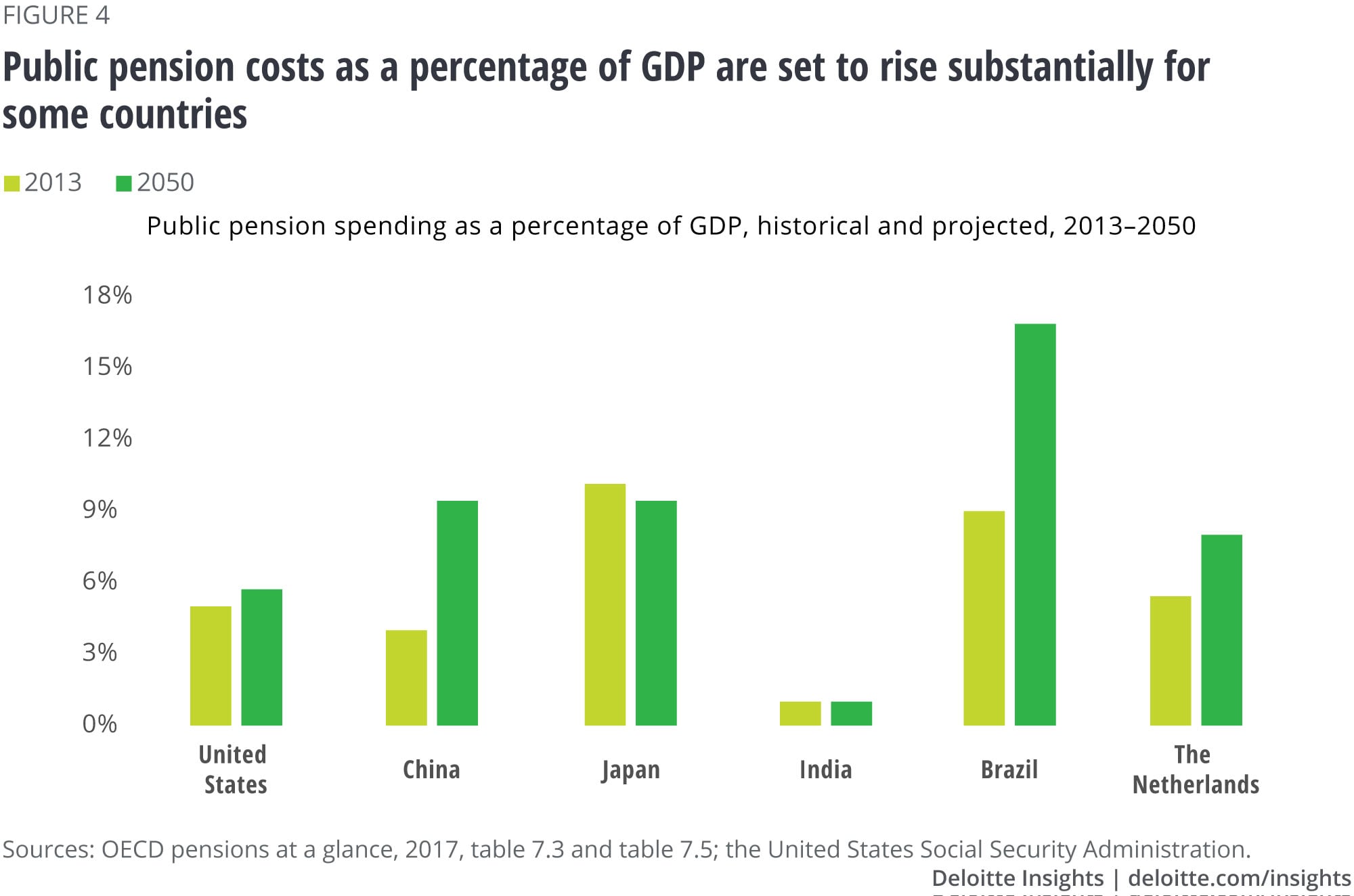

With fewer workers to support a growing number of retirees, the pay-as-you-go pension plans are going to get significantly more expensive. Three of the six countries discussed will see their public pension costs rise substantially as a percentage of GDP between now and 2050 (figure 4). India, Japan, and the United States will not see a large relative increase, but each for a different reason. In India, pension coverage is very low, and the country follows a fully-funded model. Therefore, public spending as a percentage of GDP could remain unchanged. Japan has undertaken reforms to rein in costs by changing the indexation scheme for benefits and gradually raising the mandatory contribution-rate from 13.9 percent in 2004 to 18.3 percent in 2017.40

The United States’ projected increase is not particularly large, but it is not clear how the system will be funded once the current source of public pension funds runs out. There is only one source of funds for the retirement portion of Social Security—the funds payed into the Old-Aged Survivor Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund. Until 2011, this trust fund was still growing relative to costs outlays (benefit payments and administration costs). However, according to the intermediate estimates in the 2019 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees, the OASI trust fund reserves will be depleted in 2034. After this point, only an estimated 77 percent of scheduled benefits would be payable.41 In addition, the United States has another major retirement funding issue. A large group of employees—approximately one-quarter of state and local government employees—are not included in the federal Social Security pension plan, but are covered by state and local plans, many of which are extremely underfunded.42

As for China, the public pension program faces a similar funding-crisis timeline. Public reporting indicates that accumulated pension funds are likely to peak in 2027 before running dry in 2035.43 Despite government support (more on this later in this paragraph), pension funds are likely to be in deficit in 2028 and accumulated deficits are projected to increase to 90 percent of GDP by 2050.44 For now, however, the government can and does make up shortfalls in the various plans. Each of the three two-tiered pension schemes (covering government workers, urban workers, and rural workers; detailed in figure 1) faces funding challenges. The plan for urban workers, for example, is fully funded in principle, but as the retiree population grew, administrators of tier-one funds reached into tier-two funds to make current payments. To add to this, employers fell behind in making their payments. A 2018 survey revealed that only 27 percent of companies paid their entire social security contributions.45 As a result, several individual and notional accounts at the second tier were depleted. Not all hope is lost, though, as the National Social Security Fund will likely be used to make pension payments.

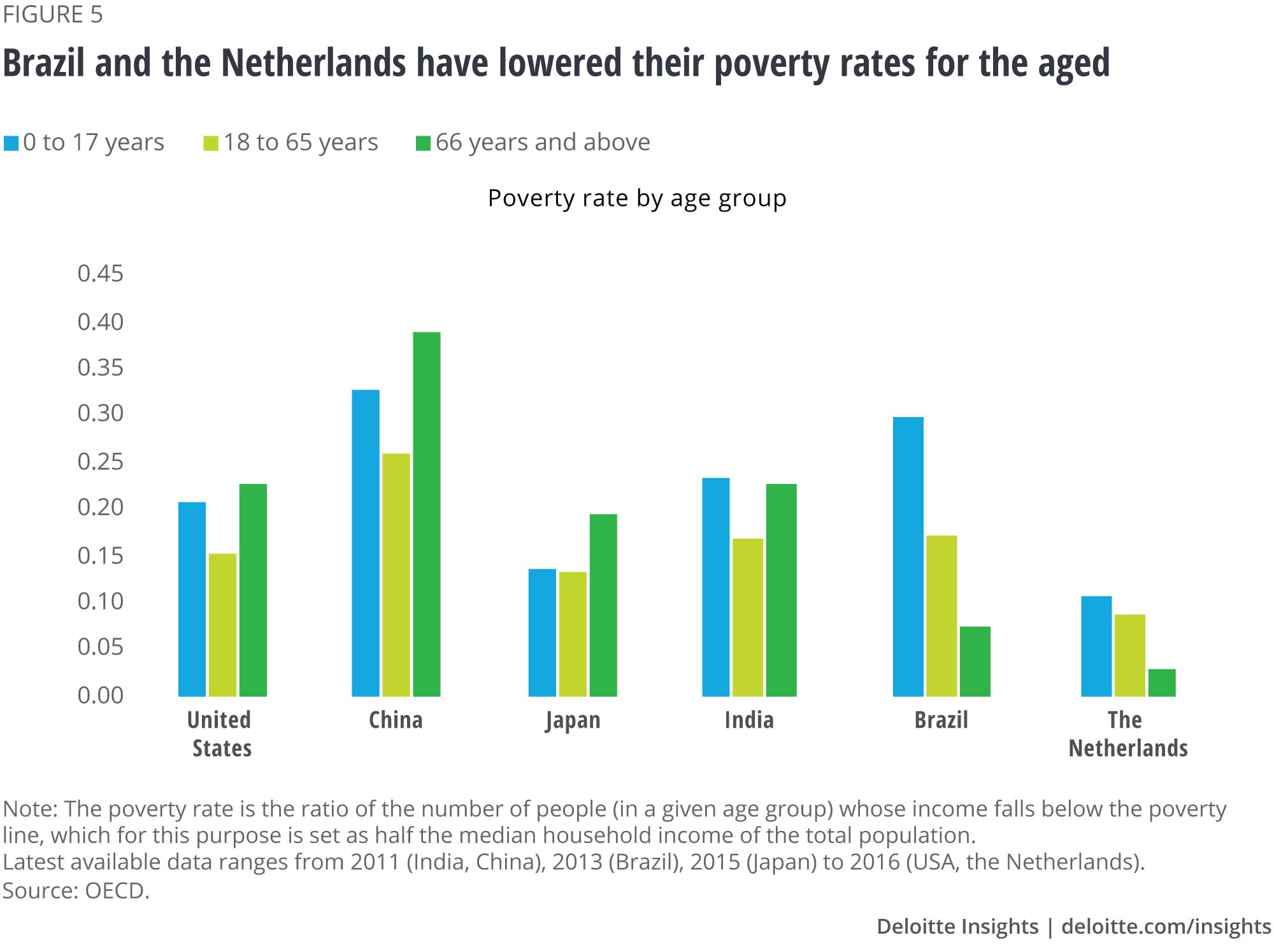

In general, the risk of poverty increases with age, and public pension funds are in a position to influence it to an extent with appropriate budget planning. For example, funds in the Netherlands and Brazil have been instrumental in reducing poverty among those over 65 to very low levels (figure 5). However, in China, the United States, and Japan, the poverty rates of the elderly are high and exceed even that of children, while in India, the poverty rate among those over 65 is roughly on a par with that of children.

Possible solutions could further increase income inequality among retiree populations

Shoring up public systems while figuring out how to lower (or at least not raise) retiree poverty-rates is a challenge. The two approaches usually considered are (1) increasing mandatory contributions and (2) raising the full retirement age. Each approach is likely to harm those at the lower end of the income spectrum and contribute to income inequality among those 65 years and older.

Income inequality has been increasing across the globe,46 and raising mandatory contributions will further exacerbate it. The fact that retiree benefits are almost always based on earnings contributes to increased inequality in the retirement phase, especially as the lower-paid workers are also much less likely to have access to private pension plans or to be able to save much toward their own retirement. There is also a substantial urban/rural divide, another type of inequality created in some countries. This is certainly true in India and China, and the state and local pension issues in the United States could also contribute to increase in geographic unevenness.

The other avenue to shore up the health of public systems is increasing the age when a person can receive full retirement benefits, but this can leave lower-paid workers worse off than the higher earners. Specifically, lower-paid workers are more likely to have physically demanding jobs and a higher likelihood of poorer health, causing them to take early retirement with smaller pensions. In contrast, the more highly compensated workers may be able to work longer, earning higher-than-full-retirement payouts (in countries that have that feature), as they accrue additional savings and private-pension balances and are able to put off drawing down assets for living expenses.

Besides these two popular solutions is the “means-testing” approach. A means-tested public pension system decides eligibility for pension payments based on income and assets. Retired workers with income and assets above a certain threshold are considered ineligible to receive full pension payments, despite having made contributions to the pension system. Such an approach, if adopted, could bolster state coffers, reduce retiree poverty, and narrow inequality after retirement by redistributing wealth. However, the approach has been criticized for discouraging savings, and transition to such an approach in countries where it does not already exist is likely to be contentious.

How will the responsibility for retirement funding change?

The current economic environment of low investment returns makes it harder for the funds to fulfill their pension obligations. As a result, there is a palpable retreat from defined benefit models to defined contribution models, with the burden of providing for the future shifting from the state and the employer to the worker.47 Defined contribution models are common in developing countries, but workers in developed countries are likely to feel unease at the idea of not being guaranteed a pension.48 Nonetheless, such a shift seems necessary from a financial-sustainability perspective.

Unfortunately, for older workers, it usually means more work and less leisure, a prospect that has been met with consternation. For instance, in the Netherlands, where the pension system is considered one of the best in the world, workers and trade unions were on strike, in June, against further increase in retirement age and proposed cuts to existing benefits.49 In Brazil, reform proposing a longer period of work before pension benefits can be availed has faced fierce opposition for decades.50 In Japan, the existing pension system catalyzes intergenerational conflict while proposed reform is usually met with political opposition. In the United States and China and even in India, existing pension systems are caught between workforce expectations and what can be provided. Amid all of this, the population of workers on the verge of retirement keeps growing … and so does the problem. The employees are increasingly focused on this issue, so too should the employers.

-

How do Americans spend their time? Infographic6 years ago

-

The services powerhouse: Increasingly vital to world economic growth Infographic6 years ago

-

America's growing generational wealth gap Infographic6 years ago

-

No college, no problem? Article7 years ago

-

Income inequality in the United States Article7 years ago