Recalculating the benefits of trade post–COVID-19 Economics Spotlight, October 2020

8 minute read

28 October 2020

With the pandemic aggravating the impact of the declining globalization growth and companies slowly moving away from China, the “world’s factory,” businesses are rethinking the structure and roles of GVCs in their operations.

COVID-19 has hit globalization growth badly. But was all well before the pandemic struck? Not quite. After World War II, globalization (measured as global exports as a percentage of the global GDP) enjoyed an upswing decade after decade due to various reasons—economic growth and integration; development of mechanisms and agreements to support and liberalize trade; China’s entry into the global marketplace; and the development of global value chains (GVCs)1 to name a few.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

But then came the 2008-09 recession. While many thought the crisis shook the world only temporarily, globalization’s march since then has never been the same. As the World Bank notes in its World Development Report 2020, the GVCs “powered the surge of international trade after 1990 and now account for almost half of all trade. This shift enabled an unprecedented economic convergence: poor countries grew rapidly and began to catch up with richer countries. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, however, the growth of trade has been sluggish and the expansion of GVCs has stalled.”2 While it’s true that globalization has suffered at the hands of COVID-19, the plunge we see today is also an extension of the downward trajectory that began in 2008.

Trade declines during recessions and the current recession is no exception. It’s no surprise that the plunge in global GDP has had a direct effect on trade. However, the situation around the current recession is different in the sense that it has been caused by a pandemic rather than a financial crisis or a supply shock, as has been the case in recent recessions. This has important implications for the types of industries impacted and the severity with which they are hit given that many individuals and governments purposely curtailed economic activity in a bid to curb the spread of the new coronavirus. Another policy response unique to this pandemic-driven recession has been the widespread implementation of temporary export restrictions primarily on medical equipment. While both of these policy actions may have implications for trade going forward, a unique facet tying the future of trade to this recession is that the virus originated in the Wuhan Province of China—a major manufacturing hub and home to many suppliers critical to production in the United States and across the globe. This has businesses rethinking the structure and roles of GVCs in their operations.

How the pandemic-driven recession is reshaping trade

The dollar value of merchandise trade fell by 5.8% in the first quarter of 2020 and by 21.1% (in year-on-year terms) in the second quarter. This is a sharper decline than the drop experienced during the financial crisis between the third quarter of 2008 and first quarter of 2009. Services trade was hit even harder, falling by 32.8% in Q1. The Q2 numbers, although based on preliminary and incomplete monthly data, indicate that services trade has experienced another substantial drop during the quarter.3

Analysis of year-over-year (YOY) data suggests that global merchandise trade fell by a fifth between Q2 2019 and Q2 2020, with all regions recording a contraction. North America experienced a 32% drop in exports and 23% drop in imports. The declines were slightly less in Europe, with contractions of 23% and 22%, respectively for exports and imports. Trade performance was uneven in South and Central America with a decline of 19% and 26% in exports and imports, respectively. As lockdown restrictions were lifted in much of Asia during the second quarter and demand for its exports improved, the YOY declines were less than other regions: a decline of 10% for exports and 17% for imports.4

The bulk of the decline in service trade can be attributed to a severe reduction in international travel as both business and personal travel was curtailed by governments, businesses, and individuals over safety concerns. Asia was hit the hardest with declines in services exported (including people traveling to Asia) and services imported (including people traveling from Asia), with the percentage decline in service exports and imports being roughly equal (i.e., -10% and -11%, respectively). The impact on North American and European services was smaller but declines in service imports (-6%) to North America exceeded the decline in services exports from North America (-4%), while the situation was reversed for Europe (-2% for imports and -5% for exports).5

Many industries have been feeling the impact of the trade slowdown, especially in the United States. In 2018, growth in merchandise trade began to decelerate before turning negative in early 2019 with both exports and imports falling (figure 2). With merchandise exports falling steeper than imports, the merchandise trade deficit has been on the increase in the ongoing recession. Exports and imports of services, however, continued to grow at moderate, but fairly stable rates until the start of the pandemic, at which time both exports and imports fell sharply and have yet to see any recovery. Services trade continues to produce a surplus, albeit in a lesser quantity at the moment.

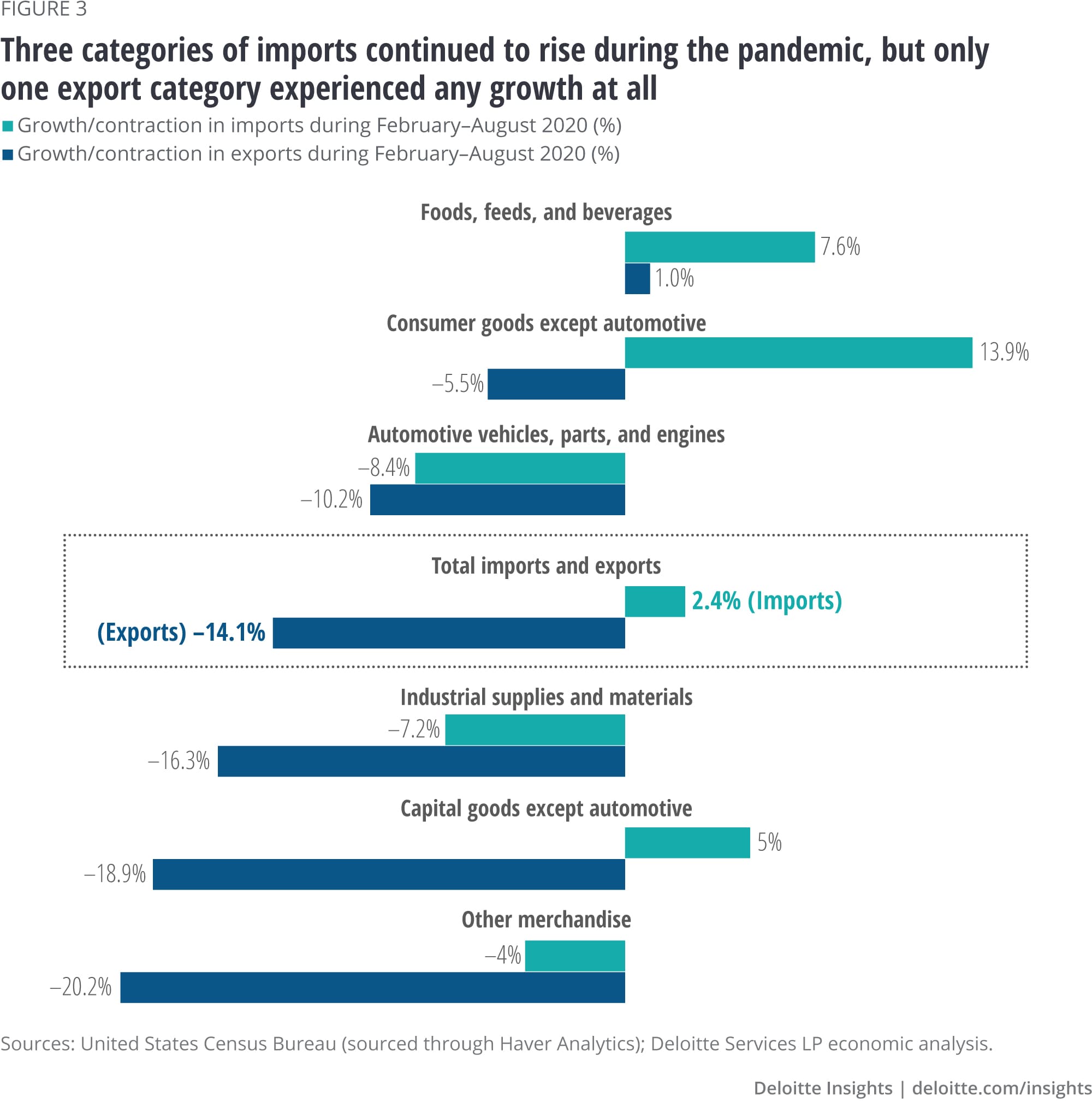

Trade in goods

With the world in recession, the United States found fewer foreign buyers to purchase its goods. Only exports of food, feed, and beverage managed to eke out a small increase between February and August 2020 (figure 3). The decline in exports—and indeed, the decline in imports—of industrial supplies and materials, however, overstates the contraction in trade of this category: energy-related petroleum products comprised around 24% of exports and imports of industrial supplies and materials in August. This is a subset that has wide price swings. Even though the value of exports and imports of energy-related petroleum products fell by 31% and 26%, respectively, between February and August, the volume (number of barrels) of both fell by less than 10%. Since industrial supply is a very large trade category, currently accounting for 33% of exports and 19% of imports in August, these wide price swings can overstate the underlying negative merchandise trade trends. The substantial increases in imports of consumer goods, except auto and foods, feed, and beverage, reflect the trends seen in retail sales—consumers are substituting goods (such as purchases in grocery stores) for services (purchases in restaurants).

One other factor that might be weighing on trade is the restrictions put in place on the export of certain medical goods, such as medicines, medical supplies, medical equipment and technology, and personal protective products (soaps, sanitizers, and face masks).6 By the end of July, nearly 90 countries, including the United States, had introduced export restrictions as a result of COVID-19.7 Globally, the United States is the top exporter and importer for each of these four categories except for medicines (where it ranks No. 6). For the United States, this grouping of medical goods accounted for 7% of goods exports and 8% of goods imports.8 These goods are scattered across the categories shown in figure 3—for example, medical equipment is in capital equipment, except automotive, and medicines are under consumer goods. While data is not available to account for the impact of these trade restrictions on trade flows, they have undoubtedly led to less trade.

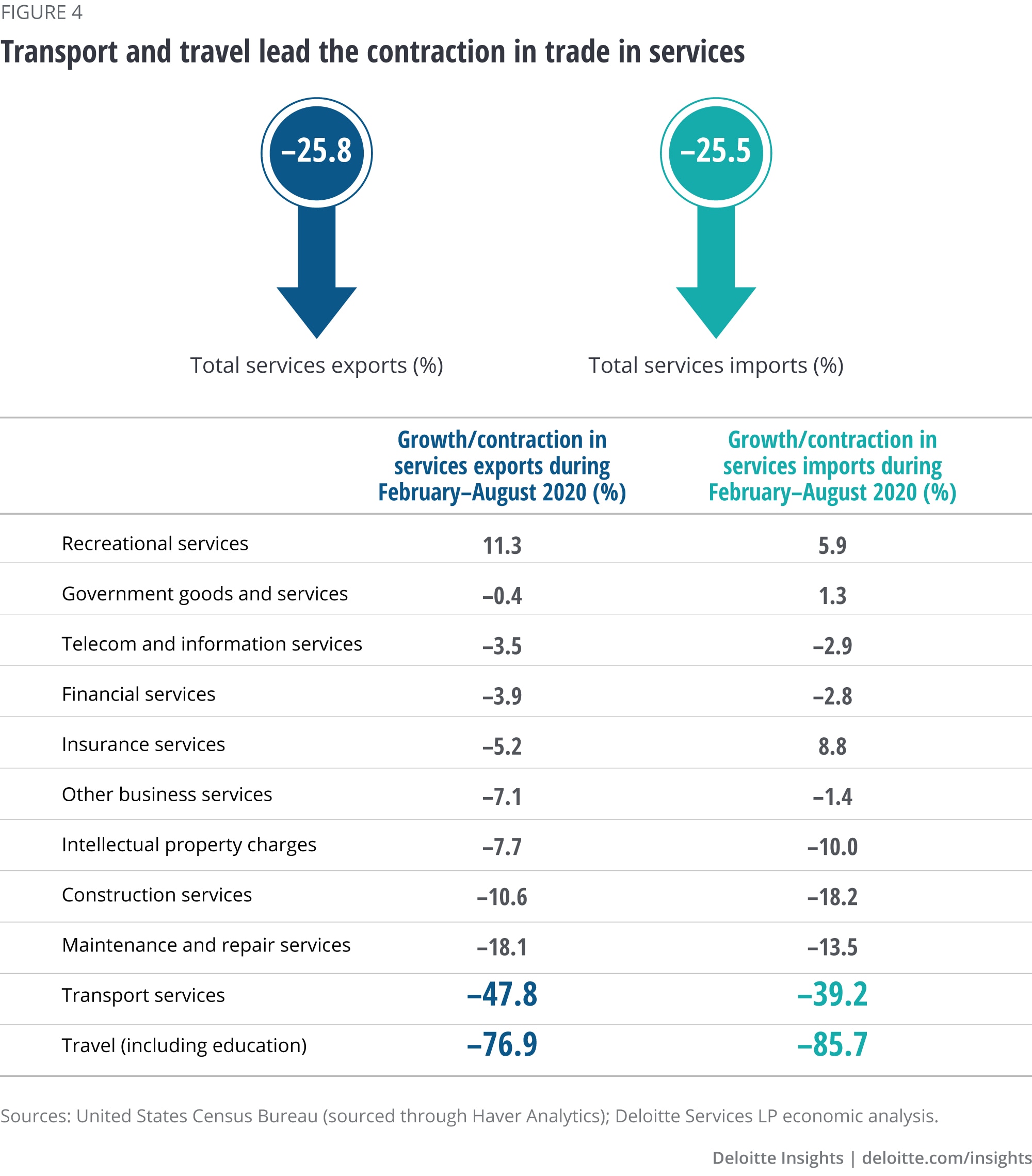

Trade in services

The only bright spot in services exports has been the 11.3% increase in exports of personal, cultural, and recreational services, which includes, on the plus side, increased exports of audiovisual services (including production, rental, and sales of audiovisual materials) and other related services such as online education, telemedicine, and sports gambling. Growth in these two subcategories has been partially offset by declines in the third subcategory related to live events. This category also had positive growth on the import side as people in the United States act similarly to people elsewhere substituting online for in-person activities, such as restaurants, bars, and live entertainment.

The two sectors with the biggest declines in both exports and imports are transport services (transactions associated with moving people and freight from one location to another and includes all modes of transportation, including air, sea, rail, road, space, and pipeline) and travel (including goods and services acquired by nonresidents while abroad for purposes of vacation, medical treatment, education, or business). The increase in imports of insurance service over the period may reflect US insurers increasing their own transfer of risk by purchasing additional reinsurance and the bulk of the reinsurance market is outside of the United States. Most of the other changes in exports and imports are likely tied to the global reduction in the economic activity.

So, what’s next for trade … and GVCs?

After an effective vaccine is developed and distributed or a new treatment option renders COVID-19 easily treated, trade, particularly trade in goods, will be able to stage a substantial recovery. However, the decline in goods trade that the United States saw starting in 2018 will require a change in the US policy to reverse. Trade wars or even threats of trade wars reduce the level of trade. As we wrote last year, “Tariffs and retaliatory actions have not only reduced the total amount of trade between the United States and China, they have also skewed the volumes of specific products being traded. However, at this point, the relative role of tariffs—compared to other factors, such as slowing growth in China—is unclear.”9 With the passing of a year, COVID-19 has not provided any additional clarity to the future of the US/China relationship.

The future of trade in services is equally murky. The level of exports of travel services in the first eight months of 2020 is around 60% below the level than it was in the first eight months of 2019 while the level of transport exports in 2020 is below 50% of its level in 2019. The strong growth in recreational services does not come close to making up the difference—in 2019, recreational services was only 8.2% the size of travel and transport. The big unknown is how much of transport and travel international trade will return?

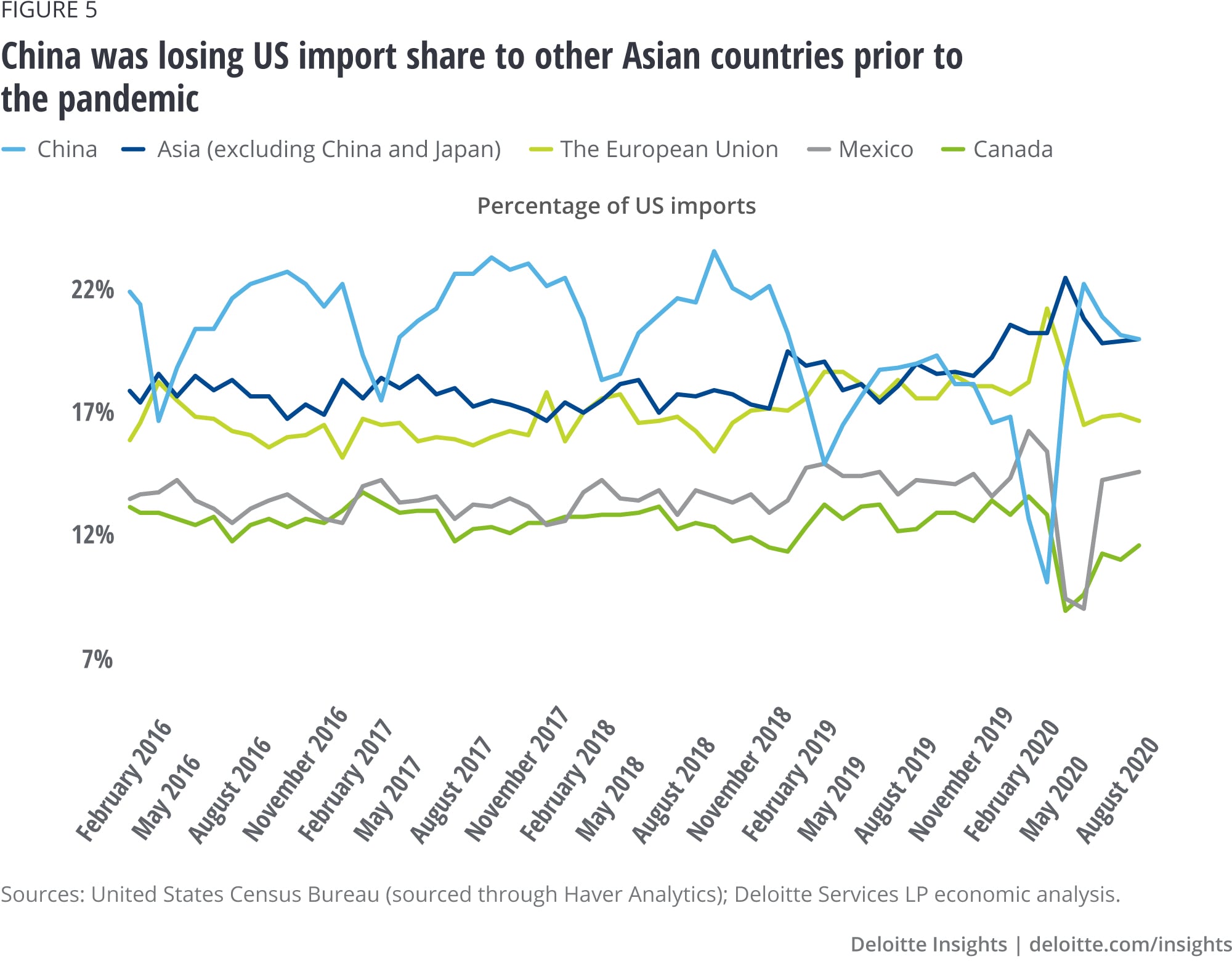

Before the pandemic, it looked like Asia outside of China and Japan was gaining on China (figure 5). It is notable that the normal spike in the share of imports from China ahead of the holiday season in the United States was muted in the fall of 2019 prior to the emergence of the virus and that China’s share of US imports did not rebound as normal as Chinese factories remained closed well after the normal shutdowns during the Lunar New Year celebrations. Even though China’s share of US imports has risen sharply in recent months, it remains to be seen if that is a temporary blip resulting from China attempting to fill backlogged orders. At present, China and Asia outside of China and Japan hold roughly equal shares of US imports. Meanwhile, Mexico has increased imports from the United States while Canada has reduced its share. Although certainly not conclusive at this point, this is some evidence of US companies moving away from Chinese suppliers in favor of suppliers in other locations.

As noted in COVID-19: Managing supply chain risk and disruption, the role of China as the “world’s factory” became a significant risk factor with the emergence of COVID-19. The shutdown of Wuhan and the loss of imports from tier 1 and tier 2 suppliers left many manufacturing firms without critical inputs. As companies work to manage risk going forward, they will be rethinking the configuration of their current supply networks. This might not be the end of globalization, but perhaps of rethinking what globalization will look like going forward in a postpandemic age.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the Economics collection

-

State of the US consumer: March 2025 Article3 weeks ago

-

Asia’s economic recovery Article4 years ago

-

India economic outlook, January 2025 Article3 months ago