What might be expected of consumer spending in a COVID-19-driven business cycle? Economics Spotlight, April 2020

9 minute read

30 April 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to hit consumer spending and trigger a recession in the United States. To understand how spending may evolve in a likely downturn and subsequent recovery, we analyze previous business cycles while acknowledging that this is an unprecedented situation.

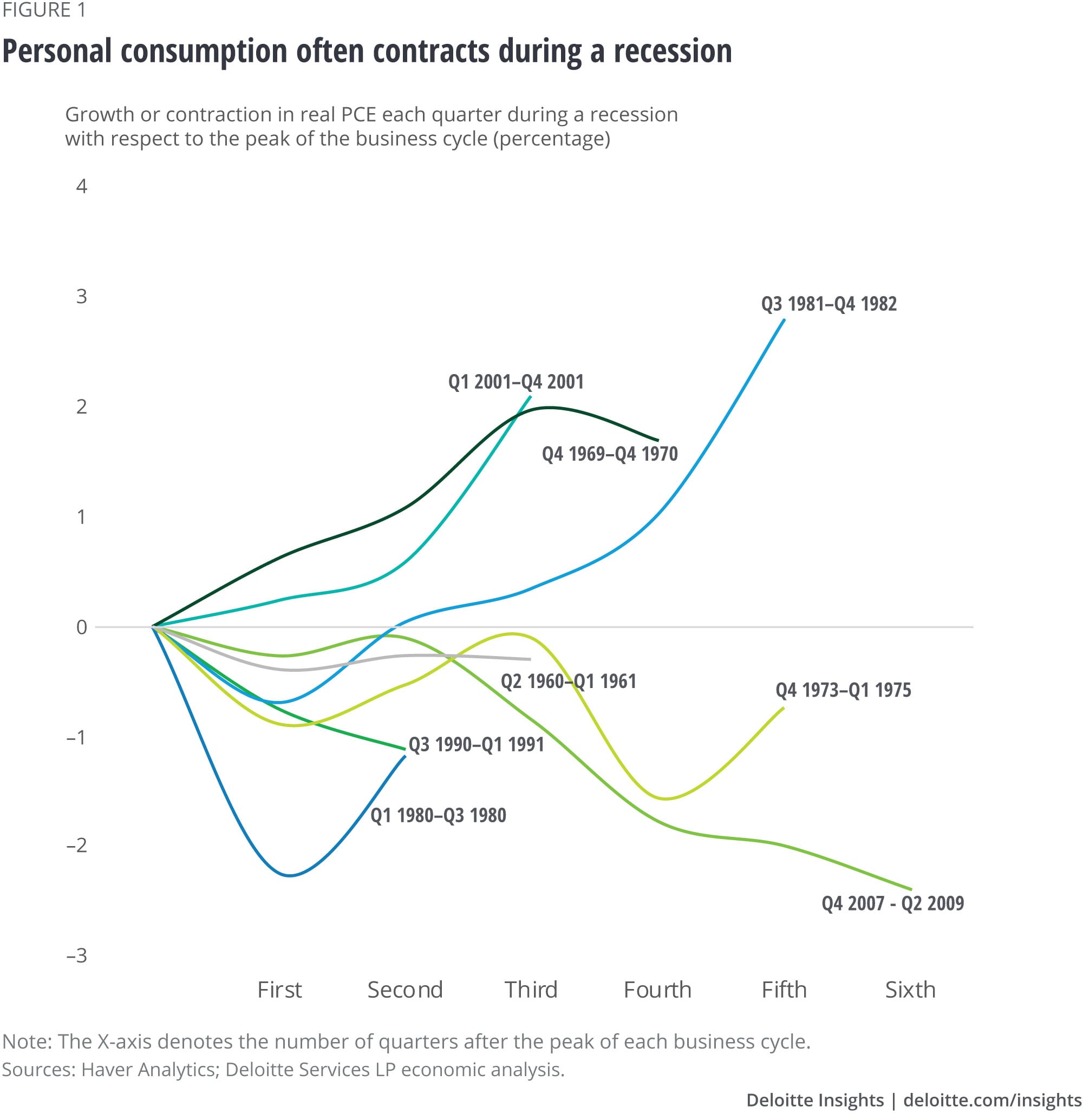

As the United States stares at a likely sharp recession this year1due to the impact of COVID-19, a key casualty will be consumer spending as households hunker down2 and businesses shut shop to prevent further spread of the virus. Analysis of data on real personal consumption expenditure (PCE)3 reveals that consumer spending often declines at times of economic contraction.4 Rising unemployment, slowing incomes, and uncertainty over economic prospects during a recession often force consumers to cut back spending and save more. PCE, for example, fell by 2.4 percent during the 2007–2009 recession.5 In fact, in every recession in the last 60 years barring the one in 2001, consumer spending has been affected (figure 1). And even in the recession of 2001, spending on durable goods—a key component of PCE—fell by 0.1 percent in the second quarter of the year before recovering.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Analysis of such consumer spending trends in previous business cycles offers insights for businesses as they prepare for potential hardships this year. Knowing what goods and services consumers generally cut back on as the economy contracts, and where the spending surge occurs as an expansion starts will help businesses plan for the subsequent recovery. Yet, it is worth noting that the scenario likely to unfold in the weeks and months ahead is very different from previous ones—the expected hit to consumer spending this time is not due to any economic factors but is a health-related one. And the scale itself may be uncharted territory for businesses.

Trends in overall PCE vary across business cycles

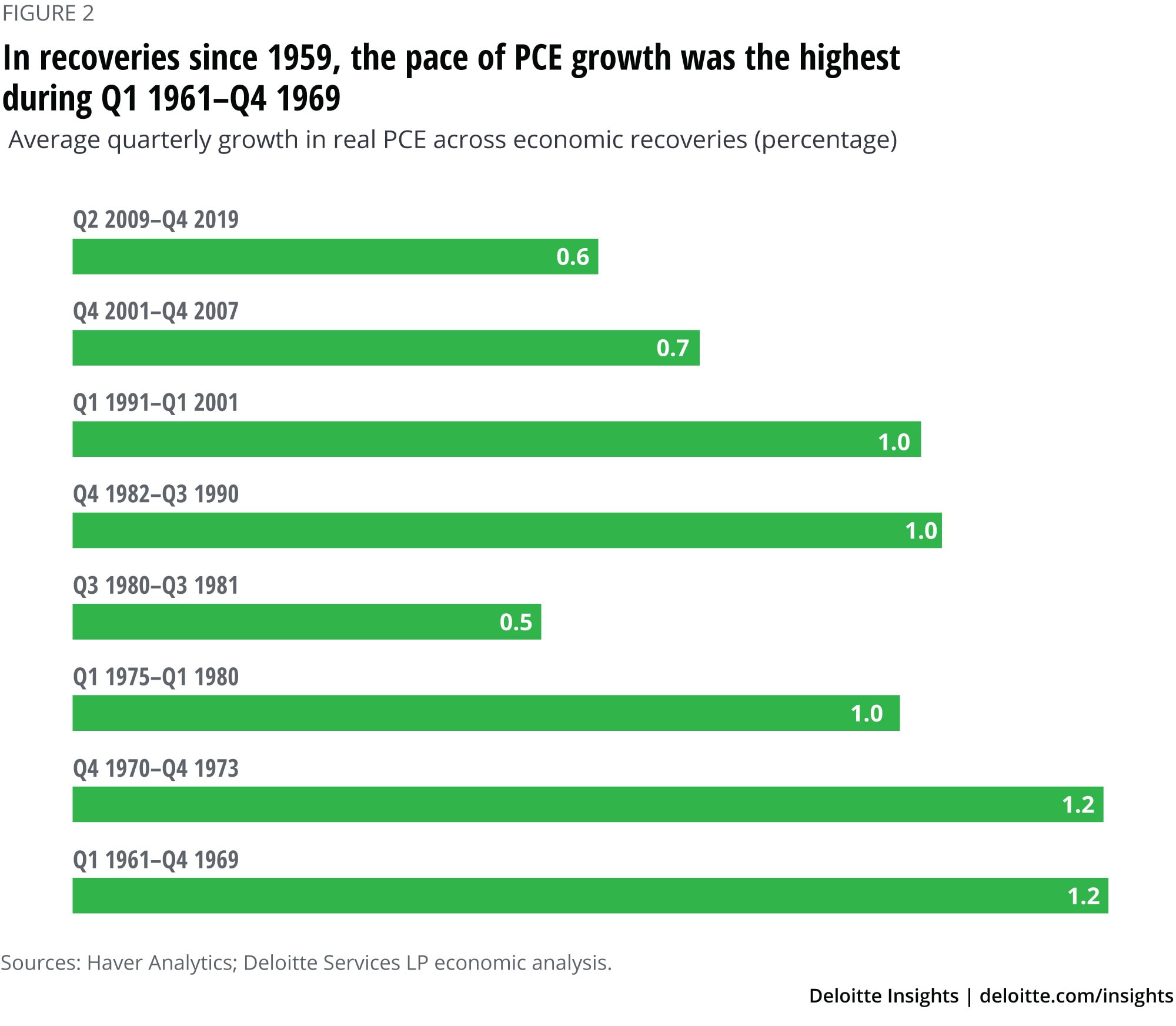

Figure 1 reveals that overall consumer spending does not follow a set pattern during a recession—spending may decline throughout a recession, at different times during a downturn, or not contract at all. The story is the same for economic expansions. It took about 11 quarters for PCE to cross its peak of Q4 2007, much more than in the previous seven recessions since 1959. That is not surprising given the scale of the economic contraction during 2007–2009. Yet, the last recession doesn’t stand out in terms of total growth in PCE in the subsequent recovery: Consumer spending rose by 28.7 percent between Q2 2009 and Q4 2019, much lower than in the economic expansions of Q1 1961–Q4 1969 (51.3 percent) and Q1 1991–Q1 2001 (47.3 percent). And not only does total growth in consumer spending vary across economic expansions, but also does the pace of growth (figure 2).

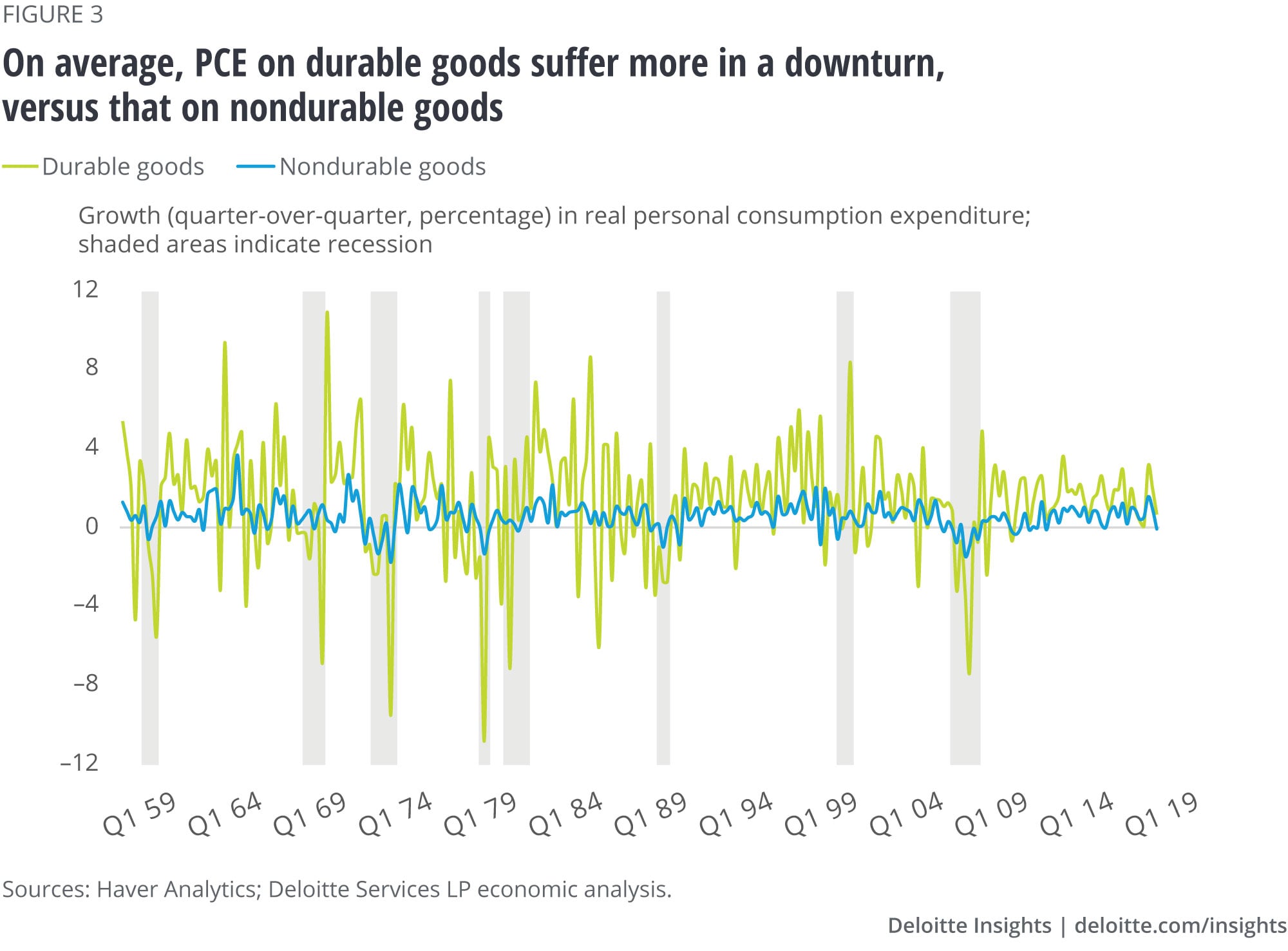

Durables are the worst hit during a downturn yet surge the most in an expansion

Spending on durable goods—a segment that includes automobiles, furnishings, and recreational goods among others—is hit relatively more during a recession than spending on nondurable goods (figure 3). After all, people spend on groceries even during a downturn, but plans to buy a new car may likely be postponed amid economic uncertainty. PCE on motor vehicles and parts, for example, fell by 21.3 percent between Q4 2007 and Q2 2009—the period of the last recession—a much steeper fall than the 2.9 percent decline in food and beverages purchases for off-premise consumption during the same period. Relative to goods—durable and nondurable—services are typically less impacted during an economic downturn. In the last recession, for example, PCE on services grew by 0.2 percent in contrast to contractions in spending on durable goods and nondurable goods.

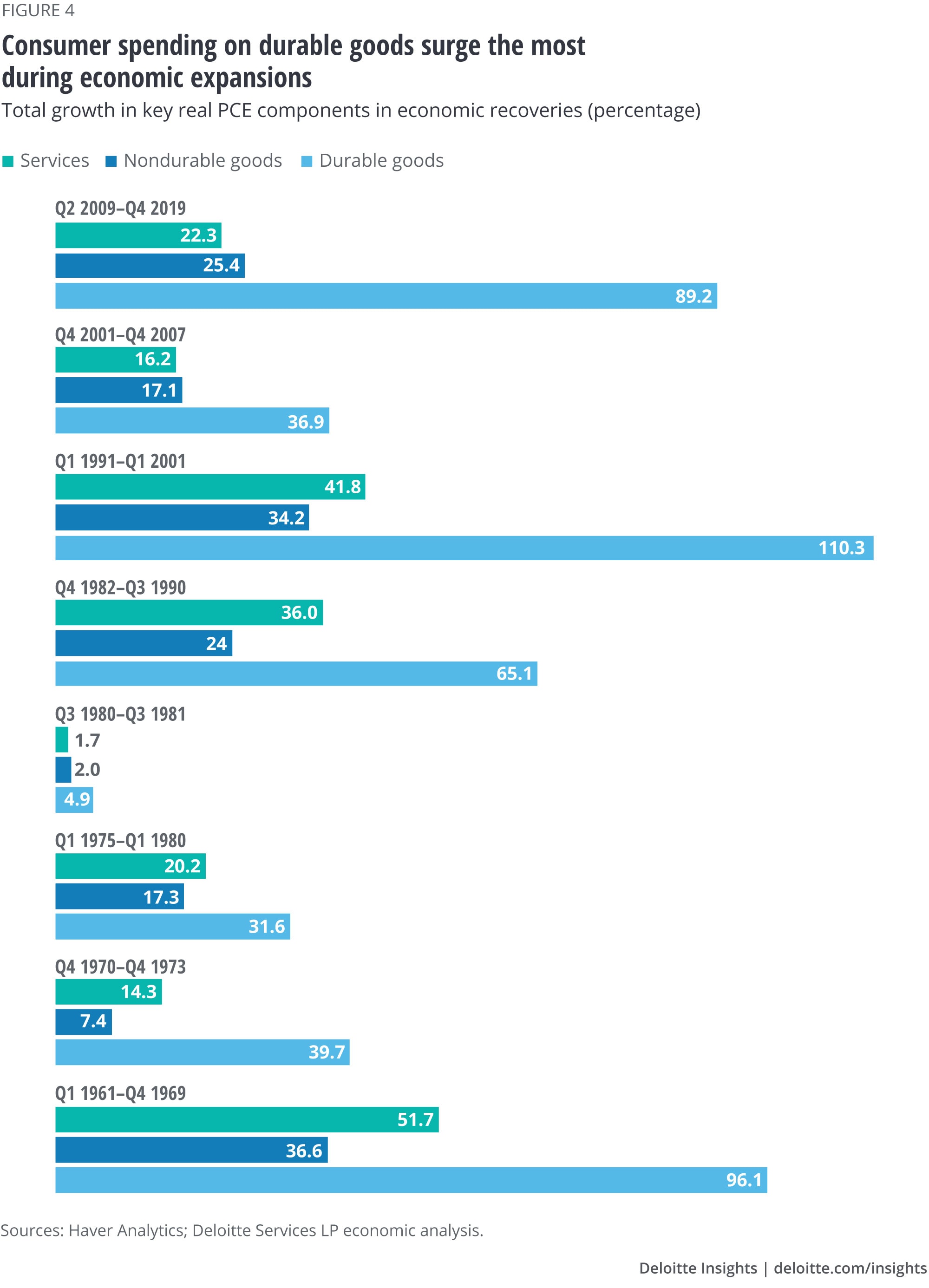

However, while spending on durables suffers the most during a downturn, it tends to bounce back faster than others in the subsequent economic recovery (figures 3 and 4). Consumer spending on durables, for example, surged by 89.2 percent between Q2 2009 and Q4 2019, much higher than the corresponding increase in spending on nondurable goods (25.4 percent) and services (22.3 percent) during this period. Figure 4 reveals that the rise in PCE in durables in the Q2 2009 expansion is not the highest on record in the last 60 years—that happened in the recovery from Q1 1991 to Q1 2001, followed by the one from Q1 1961 to Q4 1969.

To understand how spending varies across different types of durable goods, nondurable goods, and services in business cycles, we examine the period since 1990 (also see sidebar, “Why the focus on the last three business cycles?”).

Why the focus on the last three business cycles?

Comparing consumer spending across long time periods may not be ideal given that the consumption basket has changed much over the years. Back in 1959, for example, 54.4 percent of nominal PCE was goods; 60 years later, that figure had fallen to 30.9 percent with the share of services steadily increasing during this period. Even within goods, there are distinct changes in shares over this period: The share of durables in total goods PCE went up to 33.9 from 26 percent during 1959–2019. And within durables, motor vehicles and parts’ share in consumer spending has been giving way slowly to recreational goods and vehicles. A key component of recreational goods and vehicles is video, audio, photographic, and information processing equipment, and media—tablets and laptops would form a large part of this segment; these devices were barely used by consumers 60 years back.

Consequently, to keep the comparisons in spending across business cycle more balanced, the rest of this article analyzes PCE data in more detail for the last 30 years. This period includes three business cycles. A recession is the phase from peak to trough of economic activity; the subsequent expansion runs from the trough of the previous recession to the peak of the next one.

- Recession of Q3 1990 to Q1 1991, and the subsequent expansion from Q1 1991 to Q1 2001

- Recession of Q1 2001 to Q4 2001, and the subsequent expansion from Q4 2001 to Q4 2007

- Recession of Q4 2007 to Q2 2009, and the subsequent expansion from Q2 2009 to Q4 2019

Spending on motor vehicles and parts fell the most in the recession starting Q3 1990 …

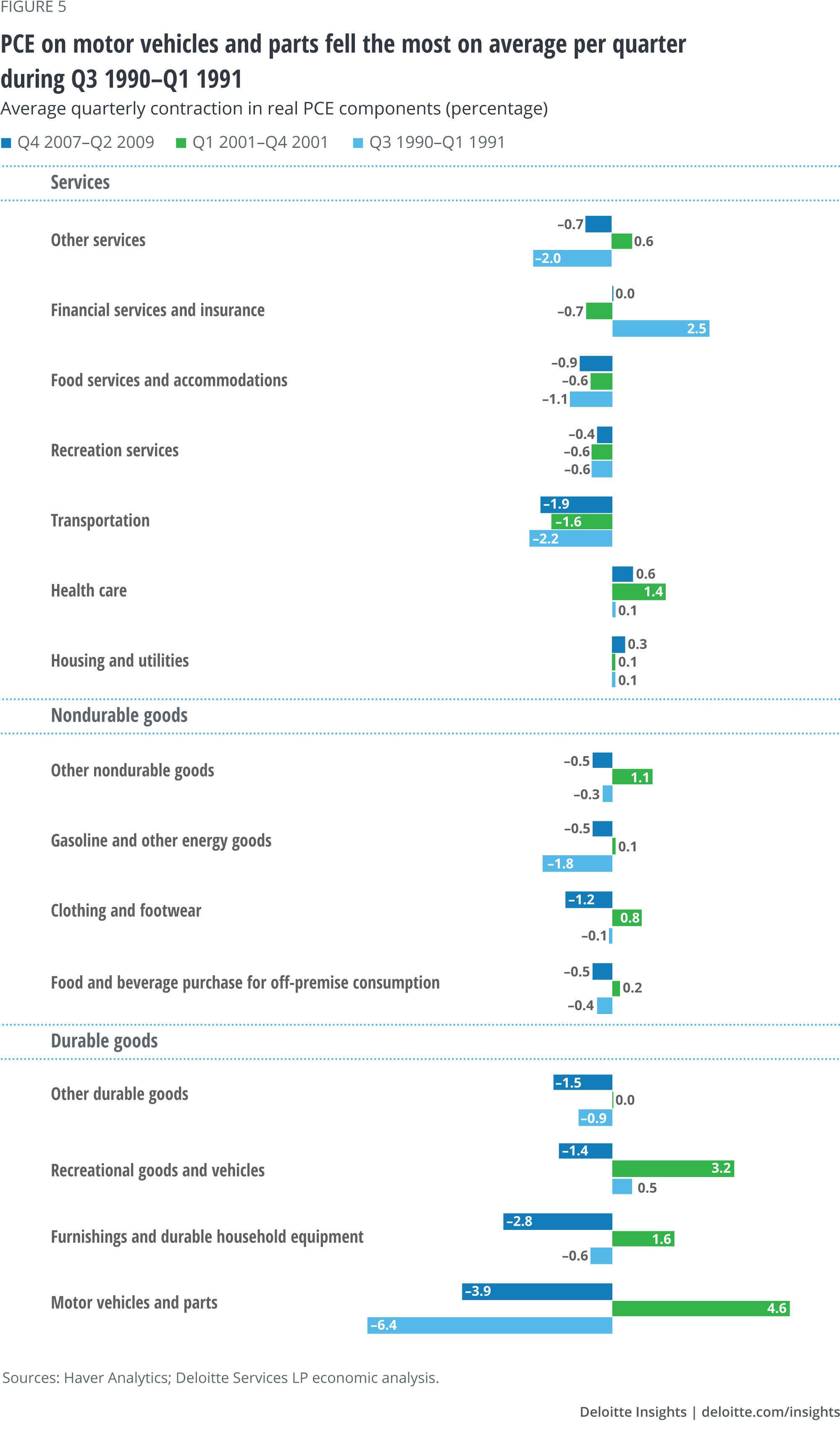

A key component of PCE on durables is motor vehicles and parts. And the segment took quite a hit during the recession of Q3 1990–Q1 1991 when spending fell by 6.4 percent each quarter on average. That pace of contraction is, in fact, the highest in all recessions since 1947 (from when PCE data is available). Among durable goods, spending on recreational goods has suffered the least in the last three recessions (figure 5). Within nondurable goods, the pace of contraction in spending was the highest for clothing and footwear in the last recession. And within services, spending on food services and accommodation, transportation, and recreation have contracted in the last three recessions. Spending on health care, however, does not show any cyclical trend—after all, ailments and their treatment are not dependent on recessions and recoveries.

A key trend that stands out is the rising spending on key PCE categories in the recession of Q1 2001–Q4 2001. No wonder then, that, overall PCE grew by 0.7 percent on average every quarter during that period, in contrast to contractions in consumer spending in the recession before and the one after.

… yet, recreational goods and vehicles stole the show in the last three recoveries

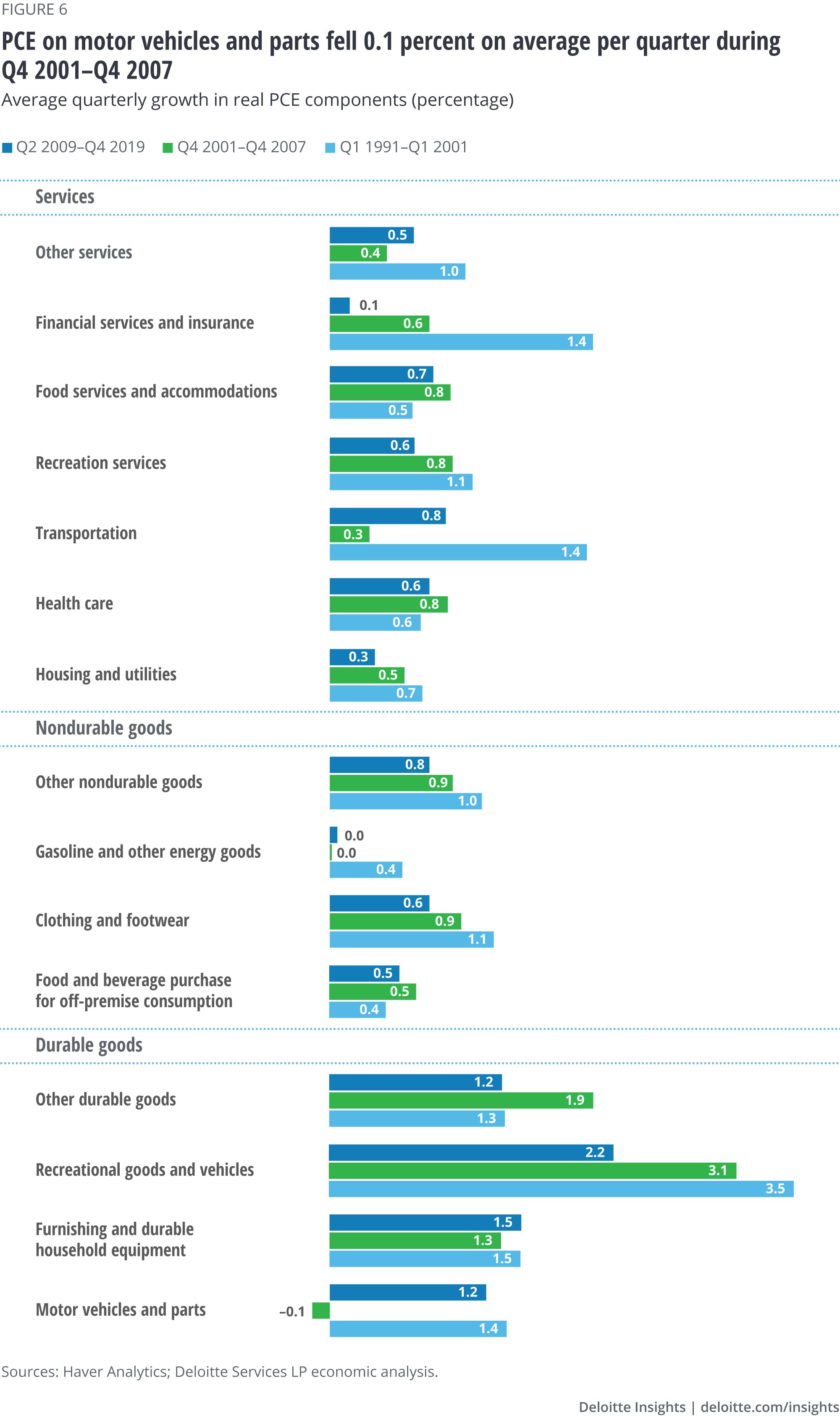

In the three expansions since 1990, spending has risen at the fastest pace for recreational goods and vehicles. Although the pace of growth in spending on recreational goods and vehicles has slowed, it was nevertheless high at 2.2 percent on average per quarter in the last expansion. While consumer spending on motor vehicles typically surges after recessions, in the expansion following the recession of 2001, spending fell slightly on average per quarter.

Within nondurable goods, the pace of increase in spending on clothing and footwear has gone down over the last three economic expansions (figure 6). This is in line with findings from the Consumer Expenditure Survey, which shows that the share of clothing and footwear on average consumer spending has gone down over the years.6 The pace of growth in spending on financial services and insurance has also slowed over the past three recoveries. Figure 6 also reveals that compared to spending on durable goods, spending on most services grows relatively slower during a recovery.

Digging deeper: Spending at out-patient departments and hospital visits don’t change much in a business cycle, but PCE on new cars does

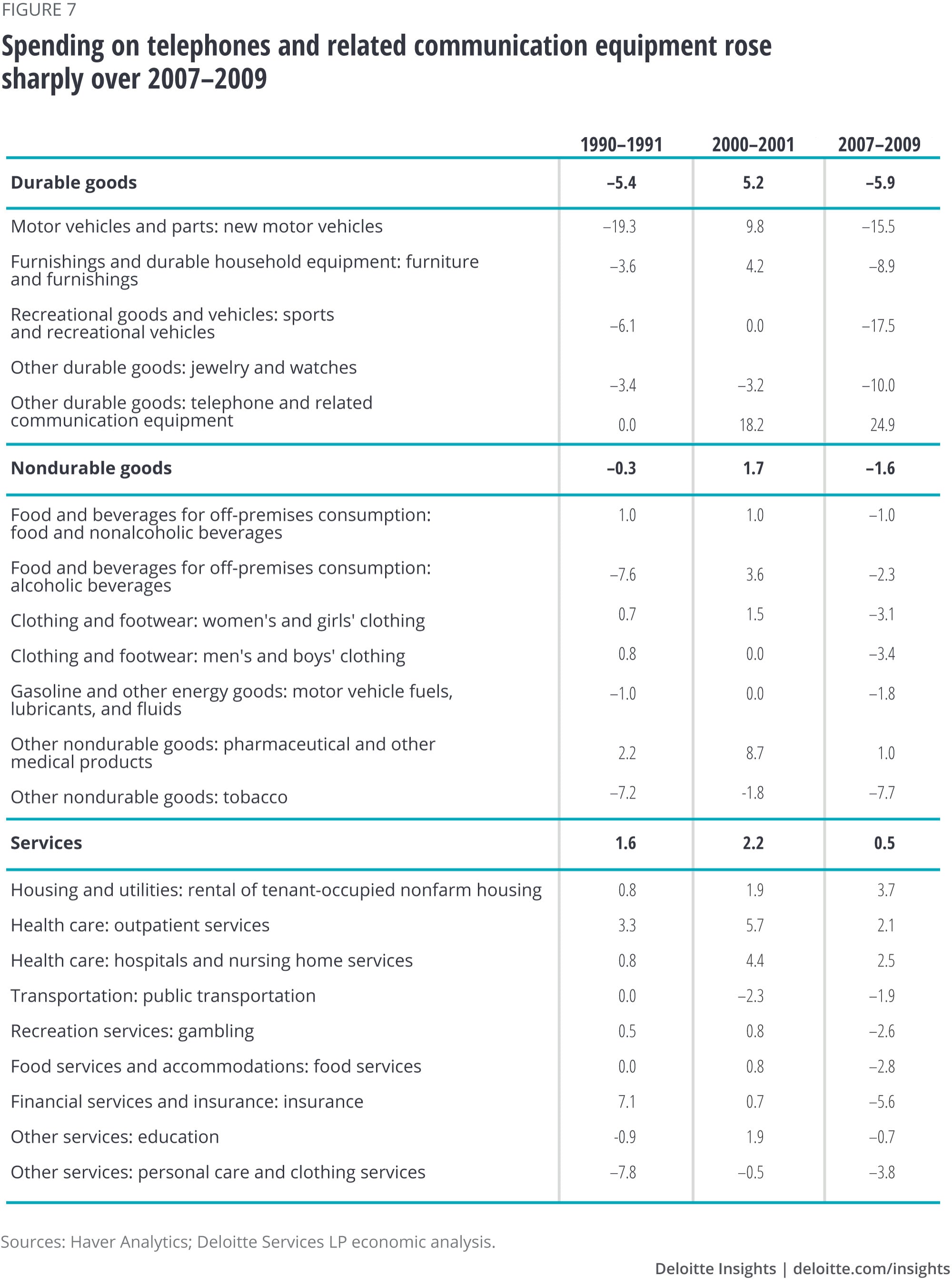

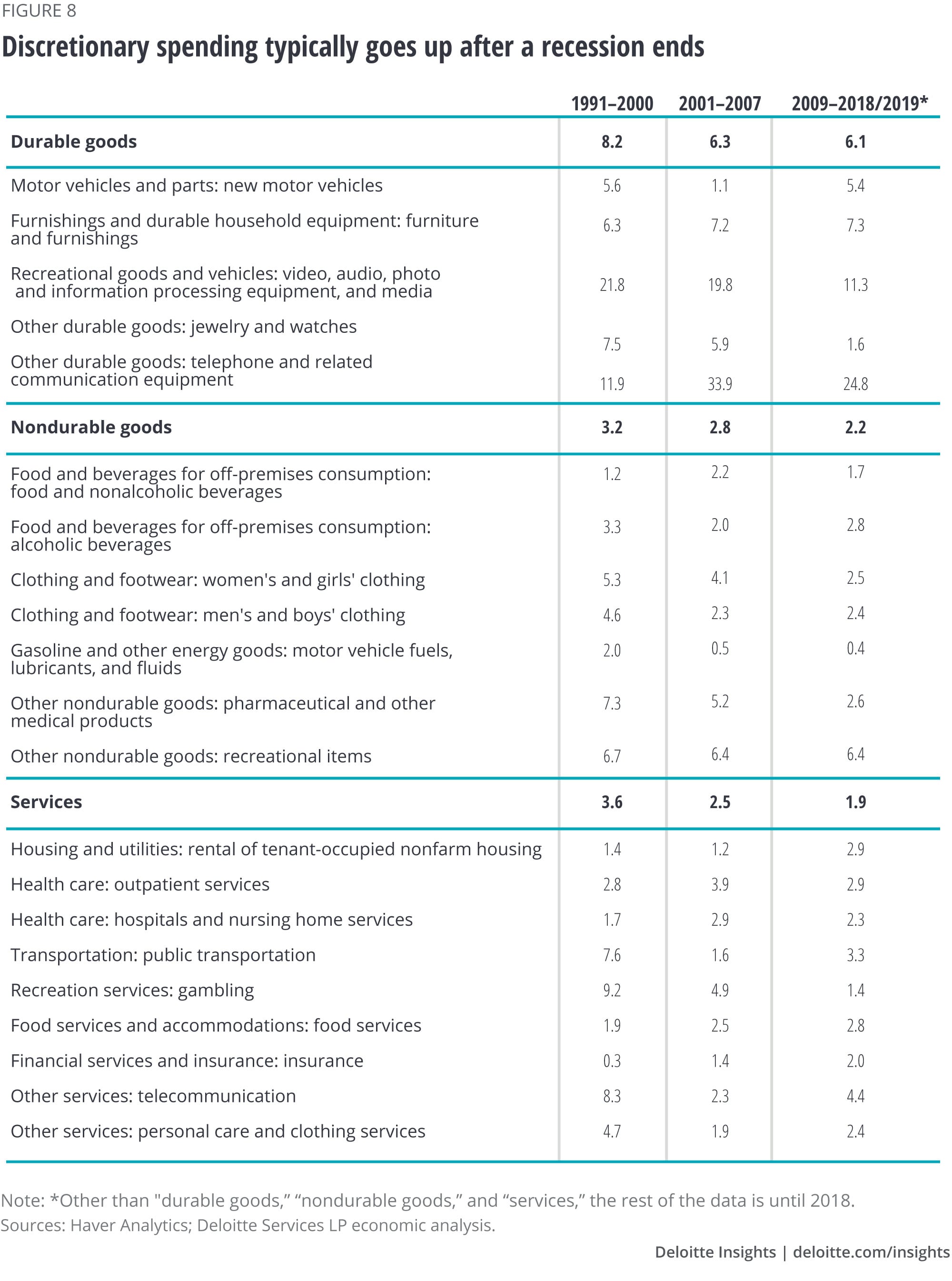

While the quarterly PCE data stops at a few broad categories, a more granular view of consumption spending patterns across business cycles is available from annual data. Figure 7 shows some key components of durable goods, nondurable goods, and services spending. Under durable goods, the most notable are strong contractions in new motor vehicles (a subcomponent of motor vehicles and parts), and sports and recreational vehicles (a subcomponent of recreational goods and vehicles) during the recessions of 1990–1991 and 2007–2009. Spending on both tend to bounce back in a recovery as figure 8 reveals.

Consumers also tend to cut down on spending on jewelry and watches during a recession. Interestingly, consumers continued to increase spending on telephones and related communication in the last two recessions, a trend that has continued into the subsequent expansions as well: PCE on telephones and related communication equipment rose by 33.9 percent on average per year during 2001–2007 and by 24.8 percent between 2009 and 2018 (figure 8).

Among nondurable goods, spending on tobacco fell in all three recessions and spending on alcohol (off-premise consumption) also fell in two of them. While purchases of alcohol bounce back in a recovery (figure 8), the same cannot be said of tobacco—it is likely that the fall in spending on tobacco in the last three business cycles is part of a trend of declining number of smokers in the economy.7

The data on services offers a few interesting insights. First, consumer spending on rent grew during the last three recessions. It rose the most in the recession of 2007–2009, likely due to the decline in homeownership.8 Second, although spending on health care continued to grow in recessions, PCE on dental services fell during the recessions of 1990–1991 and 2007–2009. Finally, given the discretionary nature of spending on services such as eating out, consumers tend to slow spending on such activities during a recession and then scale up as the subsequent recovery takes shape.

This storm’s a bit different though

While trends presented in this article hint at the goods and services that are likely to be hit most as consumers respond to the expected downturn in economic activity, the scale of the recession itself could be much harsher than recent ones. To set some context, real GDP fell by 2.5 percent in 2009 during the previous recession, the highest annual decline since 1946. This year, according to Deloitte economists, the economy will likely contract by 8.3 percent (with a 50 percent probability)—and this is actually the best case scenario.9 With unemployment likely to surge—initial unemployment insurance claims added up to a little less than 10 million in the last two weeks in March—and social-distancing measures expected to continue, it is expected consumers will cut back on spending. According to Deloitte’s baseline forecast, consumer spending is likely to fall by 4.7 percent in 2020, with spending on durables expected to contract by a staggering 21 percent.10 Spending on food services, recreation, and travel are also likely to be hit hard.

Businesses can draw comfort from the current expectation that the disease outbreak will likely begin to recede at the end of the second quarter.11 Whether households get back to their old spending habits, and how fast, will however depend much on how they emerge—economically and emotionally—from this unprecedented crisis.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the Economics collection

-

United States Economic Forecast Q1 2025 Article2 weeks ago

-

Slow growth in wages: Is the reason occupational shifts? Article5 years ago

-

US-China economic relations monthly update Article4 years ago

-

Canada Economic Outlook Article5 years ago

-

Japan economic outlook, February 2025 Article1 month ago

-

What to expect when you’re expecting … a recession Article5 years ago