Asia’s economic recovery Staggering along in an uncertain world

8 minute read

21 August 2020

Asian economies have been hit hard due to the spread of COVID-19. And recent data reveals that while nascent recoveries are likely underway in many countries, these haven’t been swift.

In Asia, home to some of the fastest-growing economies in the past decade,1 COVID-192 has put the brakes on rising prosperity. Given the virus’s health risks and the resulting need for social distancing, travel and hospitality have been hit hard, and so has consumer expenditure. With demand affected both at home and in key markets of the United States and Europe, production has weakened. The economic impact has been uneven across countries, likely due to differences in the trajectory of the pandemic so far, subsequent policy responses, and the size of the most-affected sectors in different economies.3 Until the threat of COVID-19 ceases to exist, economies are expected to underperform their potential. And any recovery is unlikely to be swift.

Economic activity is expected to contract this year in Asia

Learn More

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app.

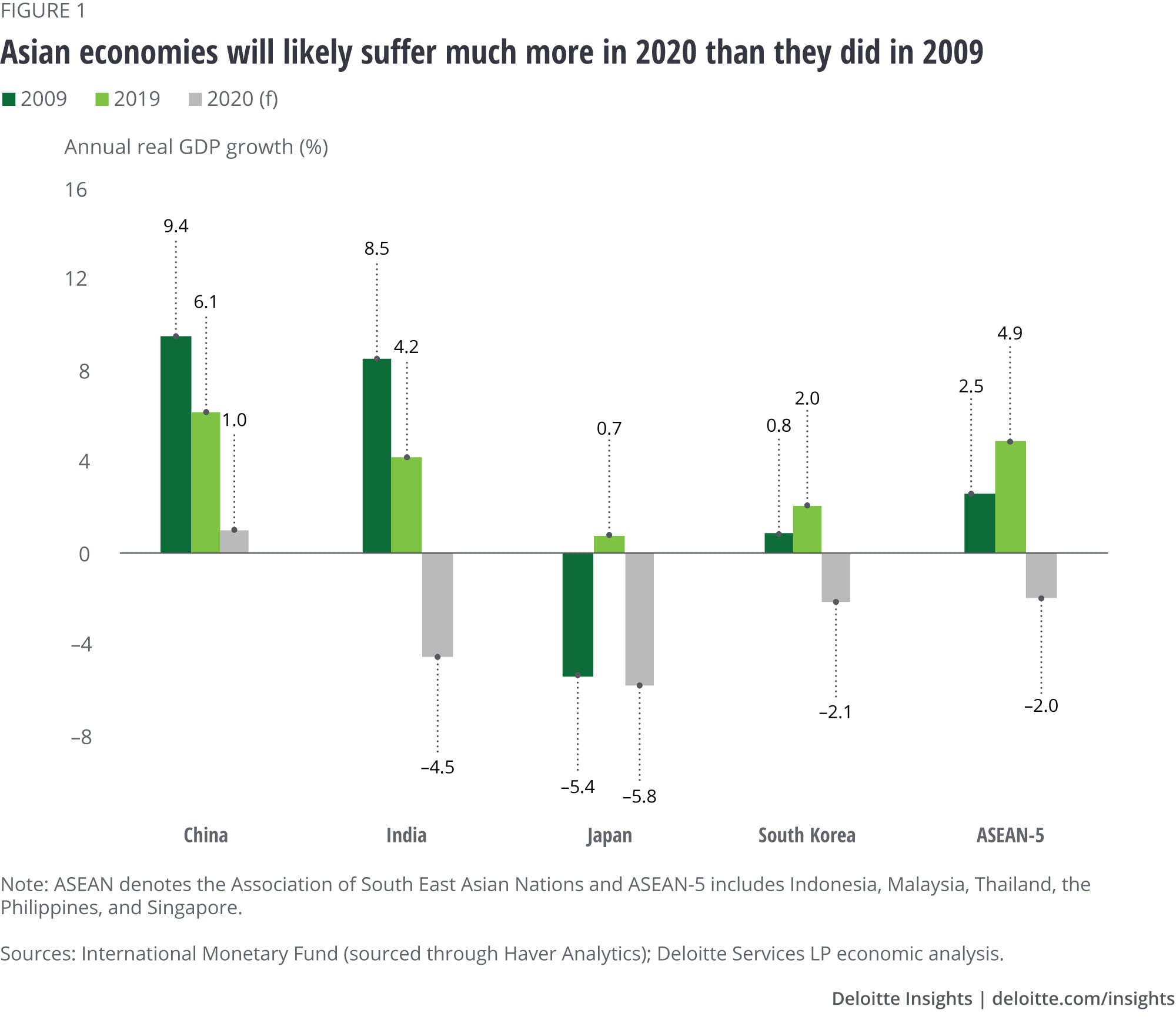

The latest trends in economic data reveal that the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 may turn out to be a small blip compared to the current economic situation in Asia. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the world economy is set to contract by 4.9% this year, compared to just a 0.1% decline in 2009 when the previous downturn was raging.4 And Asia is unlikely to escape unscathed. The IMF expects the emerging and developing Asia5 to contract by 0.8% in 2020, a sharp contrast to the 7.6% expansion in 2009 and average annual growth of 7.0% in the previous decade. Growth in China is set to slow sharply while India’s economy will likely contract in 2020. And it’s not just emerging economies in the region that are experiencing economic weakness; advanced economies like Japan and South Korea are also expected to contract (figure 1). Although growth may pick up in 2021, the scenario is still uncertain, and much depends on the trajectory of the pandemic.

Lockdown and reopening: A tale of two woes

To thwart the spread of COVID-19, many economies were quick to enforce lockdowns and social-distancing measures, but these all but halted a large share of economic activity. Over the past few months, economies have begun to reopen, with varying degrees of social-distancing measures still in place—and with mixed country-level experiences. Regardless, people remain worried about their well-being,6 thwarting a return to prepandemic levels of activity.

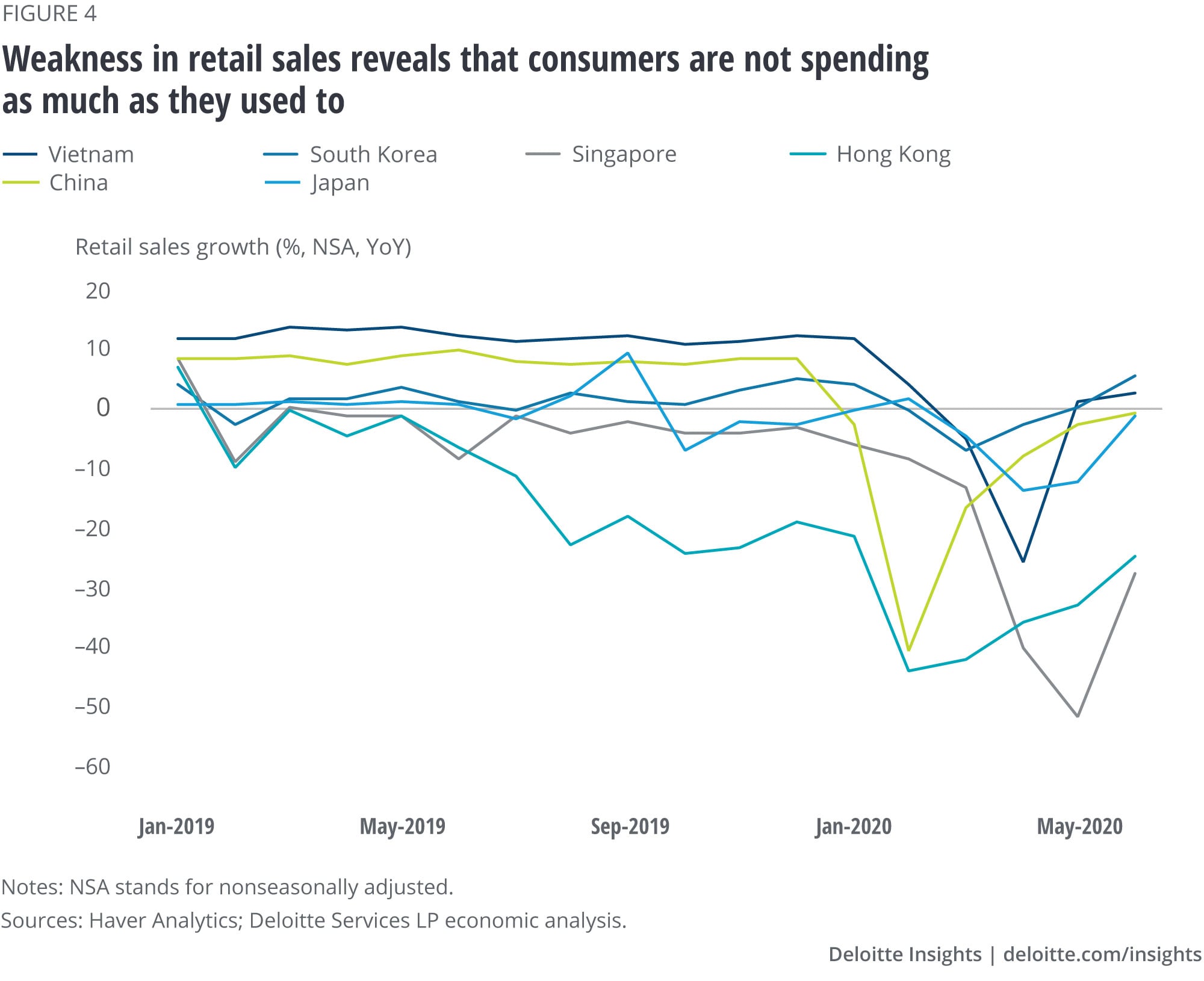

Phase 1, lockdowns and social distancing

China enforced lockdowns mostly in Q1 2020 and India in mid-March and extended them till early June. Expectedly, consumer spending fell sharply. In China, retail sales fell 19.6% year over year7 in the first quarter compared to an 8.3% rise in the same period a year before. In South Korea, sales fell 3.3% in March when daily new cases of the virus peaked. Spending on nonessential items and in establishments where social distancing is difficult was hit the hardest. A good example is sales at restaurants and bars. In Hong Kong,8 business receipts in food services fell by 31.2% in Q1, while in Singapore, where cases rose again in April and May, the index for food and beverage services fell by 51.9% on average.

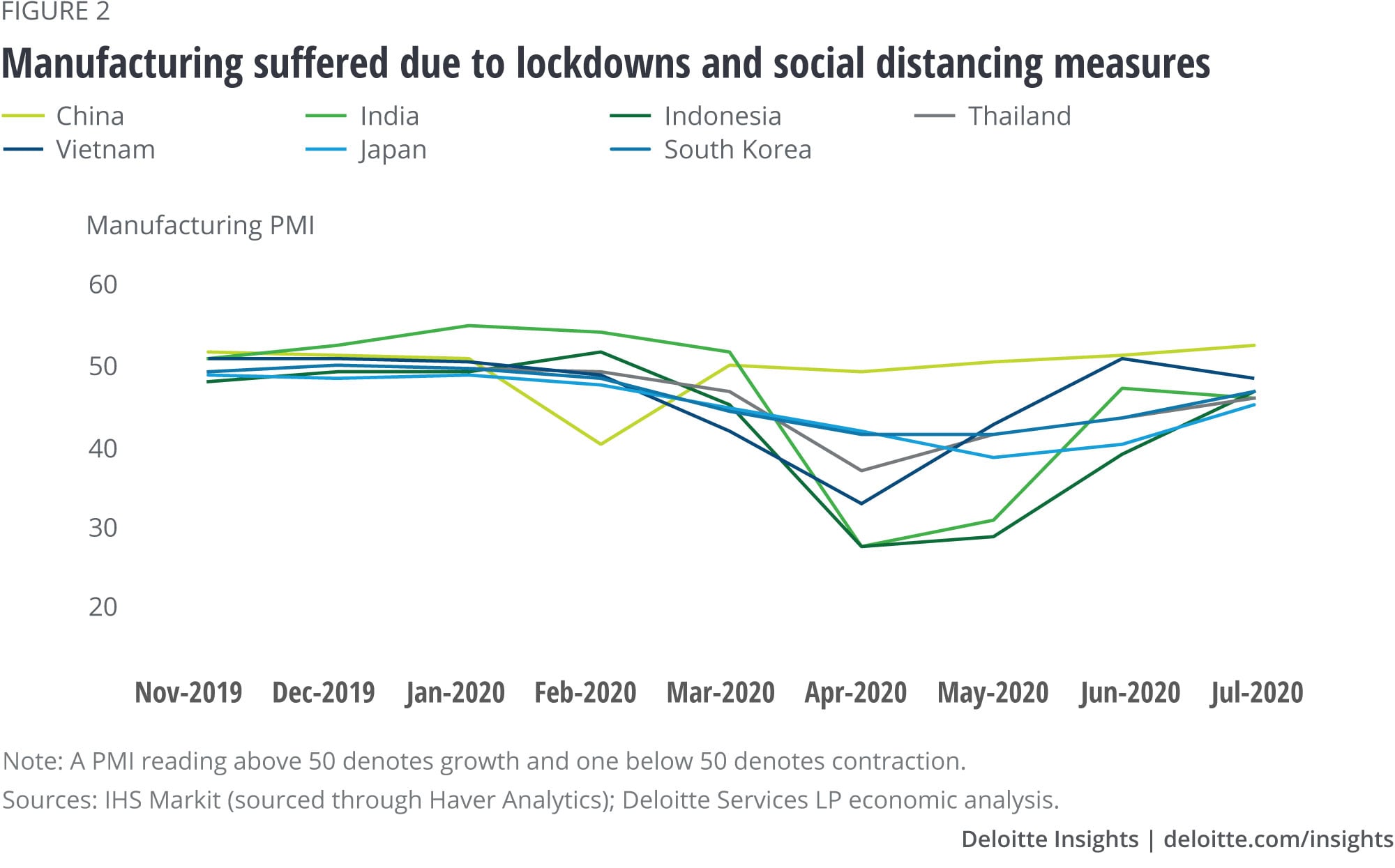

As for manufacturing activity in China—as measured by the purchasing managers’ index (PMI)9—it fell sharply in February before bouncing back in March (figure 2). India and Indonesia were affected most in April and May, while in Japan, where strong restrictions were in place from mid-April to mid-May, the steepest decline in manufacturing activity was in May.

For economies in South Asia and Southeast Asia that have large tourism sectors, the pandemic and continuing restrictions on travel have meant that tourism incomes have dried up. In Thailand, international tourist arrivals dropped 42.8% in February, 76.4% in March, and then fell to zero in April and May. The trend is similar for other key tourist destinations in the region (figure 3). Smaller and less-diversified economies, such as the Maldives and even Sri Lanka, seem set for a bigger impact on growth. For example, with tourism interlinked—directly and indirectly—to nearly two-thirds of the Maldivian economy, the jolt to the sector this year will likely result in strong GDP contraction.10

Air travel too has suffered a lot due to travel-related restrictions, which continue to be in force in many countries. Passenger movements at Changi Airport, Singapore, fell by 99.5% in April and May.11 Other air travel hubs like Hong Kong and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, show similar declines in passenger traffic.12 According to the International Air Transport Association, passenger traffic for Asia-Pacific airlines is forecasted to fall 53.8% in 2020, thereby leading to a 27.5% fall in revenues.13

Phase 2, unlocking and the absent V-shaped recovery

Removing lockdowns didn’t result in a swift move back to pre-COVID-19 levels of economic activity. There are three reasons for this. First, some “unlocked” economies still have a high number of cases. In India, for example, new cases averaged over 35,000 per day in July. This means that although the economy isn’t in lockdown, social distancing regulations are still in place, including local lockdowns and reduced capacity in offices and business establishments. Second, even where countrywide virus cases have dropped, local virus clusters are still cropping up. For example, in June, there were fears of a cluster in Beijing, China, and small clusters emerged around Seoul, South Korea.14 Consequently, social-distancing measures are still in place. Last, but not least, no cure or vaccine has been found as of the writing of this article. So, even as economies open, people and governments are being cautious. Restrictions on large gatherings and travel are still in force in countries while people limit their movements for fear of catching the virus.

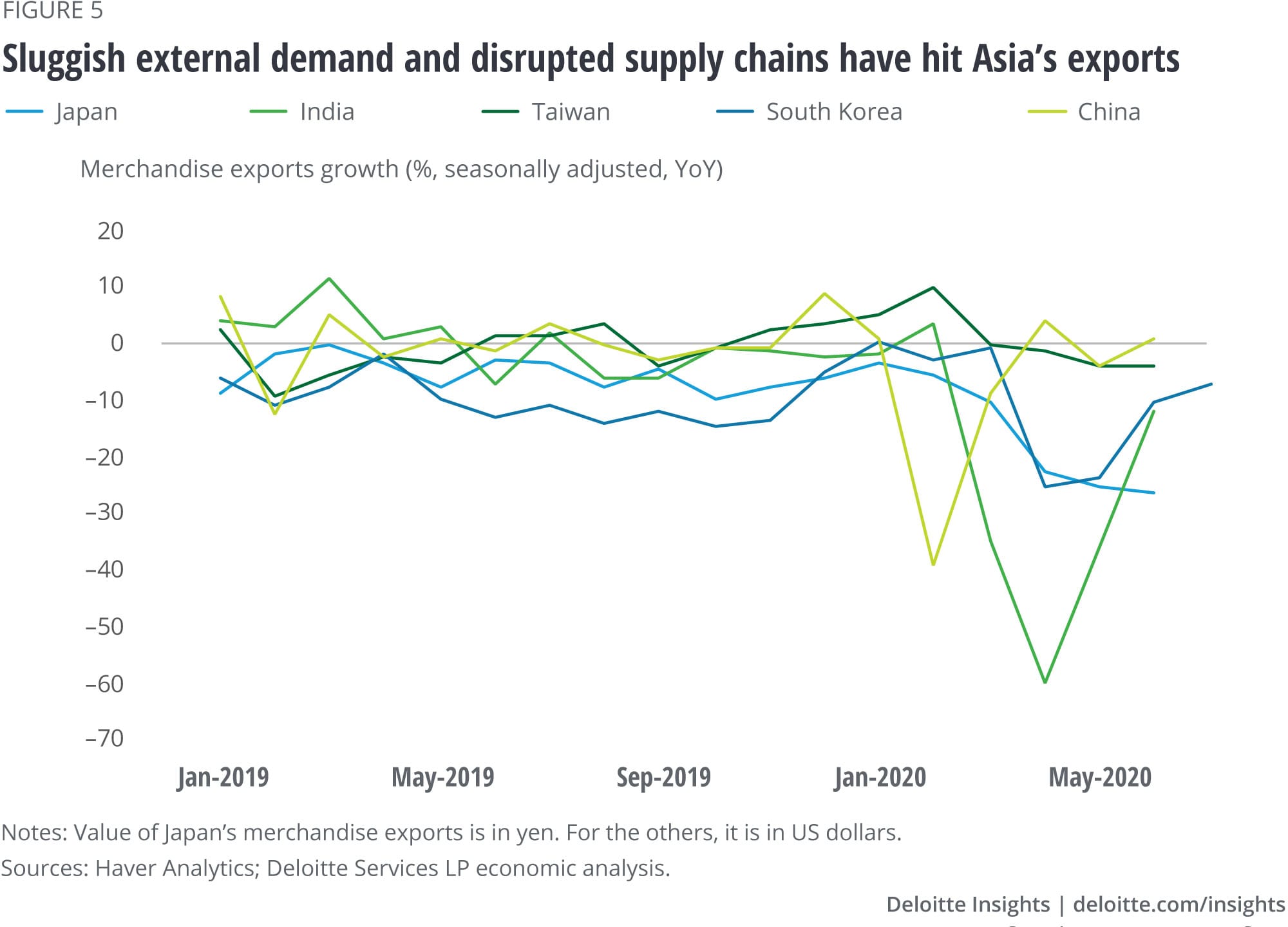

Given this situation, key sectors continue to lag. Manufacturing has rebounded in some countries but remains below pre-COVID-19 levels (figure 2). Meanwhile, consumers are still holding on to their purse strings. Retail sales, for example, may have rebounded a bit in South Korea and Vietnam, but the dip in sales continues for others. Similar trends in key markets outside Asia means that Asian exporters continue to feel the pain of weak external demand (figure 5).

Interestingly, although economies are slowly picking up the pieces, not much has changed for tourism and aviation. Travel restrictions, especially those on international travel, remain. It is also unlikely that people will flock for vacations within their country given risks from the virus itself.

Stimulus in the time of uncertainty: It’s a slippery slope

While Asian economies are expected to continue recovering, the recoveries are unlikely to be fast or complete until better treatments or a vaccine makes its way to a large share of the region’s (and the world’s) population. Even in China, for example, where the virus is relatively more in control, a return to growth in Q2 is welcome news, but the 3.2% rise is far lower than the 6.2% expansion in the same period a year before. Unfortunately, as of writing this report, there is no approved vaccine although there are several ongoing trials around the world.15 Even if a vaccine is found eventually, ensuring its supply and delivery will take time, especially in countries with large populations, such as China and India.

In such a scenario, there is a limit to how much governments can do—or achieve. While fiscal authorities and central banks have been quick to support economic activity in the short term, a decision on whether to continue doing so and to what degree will depend on prevailing fiscal conditions and the need to hold firepower for later if the pandemic continues. Emerging economies in the region will also be wary of stress on sovereign ratings from any fiscal deterioration and its impact on their currencies. And any attempt at credit-fueled consumption will likely not be effective if people remain anxious about the virus. Also, funneling too much credit into the economy may lead to deteriorating debt levels, as happened to many countries after the global downturn of 2008–2009.16 In China, for example, overall debt surged to 317% of GDP in Q1 2020 from 172% back in 2008.17 Central banks will also likely be wary of a rise in business bankruptcies if economic growth doesn’t revive fast.18 Such bankruptcies will worsen the burden on countries already dealing with high nonperforming assets, such as India.19 Interestingly, if travel restrictions and social-distancing requirements continue, sectors such as food services, tourism, and aviation are at a higher risk of bankruptcy. Given that sectors such as tourism are labor-intensive,20 any rise in insolvencies there may lead to higher unemployment, poverty, and income inequality in some economies.21

A possible double whammy could be any escalation in restrictive trade and investment practices. To this end, Asian policymakers will be hoping that rules of global trade and finance outdo the protectionist rhetoric in many parts of the world,22 and that the pandemic itself enables more global cooperation to race to find a vaccine or better treatments. That would be one gift that the region and the world can do with.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore our COVID-19 content

-

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

US Economic Forecast: August Update Article4 years ago

-

The long and short of short-time work amid COVID-19 Article4 years ago