Digitally engaged? Asia leads the world has been saved

Digitally engaged? Asia leads the world Voice of Asia, May 2017

16 May 2017

Digital engagement indices for government, business, and consumers clearly show that Asian economies are ahead in terms of digital engagement, with almost all Asian countries above the world average.

Economic takeaways

- Asian countries are winning the race for digital engagement against global peers with similar levels of economic development.

- This will underpin Asia as the focus of global economic growth over the coming decade.

- Government and business engagement is high relative to the rest of the world, but individual engagement is about average.

Explore Voice of Asia

Asia winning the race on innovation, growth, and connectivity

Economic growth and development in Asia

Voice of Asia is also available via PDF in the following languages:

Embracing digital technologies is central to Asian countries’ development strategies. Indeed, Joseph Schumpeter, one of the 20th century’s most influential economists, observed that innovation is the determinant of economic development.

But it all starts with engagement.

We take a look at digital engagement indices for government, business, and consumers. These indices show how Asian economies are more digitally engaged relative to global peers at similar stages of development.

Firstly, the indices present Asia relative to the rest of the world, and secondly, we drill down within Asia to consider the digital intensities of different countries and the likely changes over time.

Engagement indices

Digital technology has the potential to change economies and societies dramatically, but engagement is critical to reap the benefits that technology offers. Governments, businesses, and individuals need to actively participate in the digital world, and this happens to varying degrees globally.

There are many indices which measure different aspects of digital engagement; however, given the vast number of factors that comprise engagement, there is no widely agreed upon definition or global ranking.

Two of the most comprehensive indices are:

- The World Economic Forum’s Networked Readiness Index (NRI), which measures the performance of 139 economies in leveraging information and communications technologies (ICT) to boost competitiveness, innovation, and well-being

- The United Nations’ ITU Development Index, which is based on access, use, and skills sub-indices in relation to ICT

While country rankings may vary between the two indices, it is clear that Asian economies are performing well. The indices prioritise different measures, but Asian economies are consistently highly ranked. For example, Singapore is ranked 1st on the NRI and South Korea is 1st on the ITU Development Index.

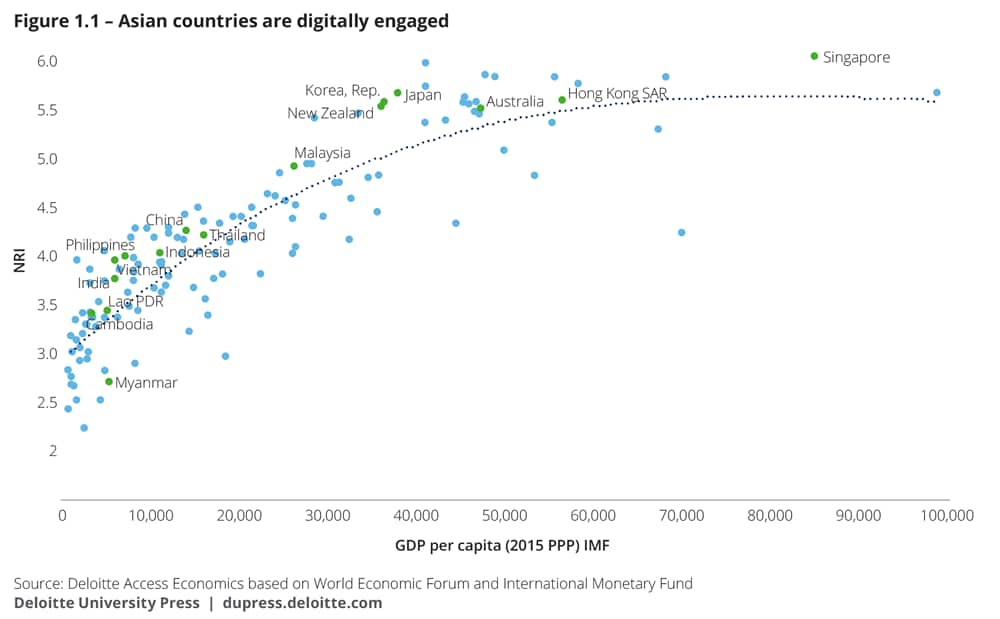

Figure 1.1 graphs each country’s NRI score against GDP per capita. Every country in Asia, apart from Myanmar, lies above the line of best fit, indicating above-average levels of digital engagement for the level of their economic development (as reflected by GDP per capita).

The graph clearly shows that Asian economies are ahead in terms of digital engagement, with almost all Asian countries above the world average. Singapore and Hong Kong are world leaders, while Japan lies in a group that has advanced network readiness, showing that higher use of digital technologies can lead to immediate gains. The large population bases in countries such as China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam have considerable opportunities waiting to be embraced.

Indeed, countries that have a high NRI score and low GDP per capita are poised to take advantage of the economic benefits that digital will bring. Countries in this group are well positioned to use increasing adoption of digital as an enabler for development. Countries with high per capita GDP, like Japan, can also benefit from the innovative use of digital technologies to increase productivity and generate the surplus needed to sustain the economy. This shows that the move to digital is for everyone across the region, as innovation via digital means the region can provide new sources of competitive advantage, create new jobs, and help alleviate socio-economic challenges.

Deeper insight and analysis

Economic takeaways

- In middle-income Asian countries, governments have been able to maintain strong growth agendas based on policies in areas such as trade, infrastructure, and savings. Today, these countries are pursuing growth agendas, with digital playing a leading role.

To better understand what is driving these results, Deloitte has created engagement indices specific to government, business, and individuals in a country. These indices give deeper insight and analysis into where economies are utilising the potential of digital, and where they could improve.

Figures 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4 graph government, business, and individual digital readiness against GDP per capita. The appendix provides details on how these indices were constructed.

When it comes to the roles government is playing, some broad trends can be observed across all countries:

- There is a relatively low level of engagement in the least developed economies because of constraints on public finances

- As economies develop, governments tend to adopt a proactive approach in many areas of economic development (including trade, infrastructure, and encouragement of saving), and their approach to digital is no different

- As the economies develop further, consumers and market forces come more to the fore in driving innovation and economic growth, with governments facilitating these forces through policy and regulation rather than direct active involvement

Do Asian economies follow these trends? Broadly speaking, they do appear to do so, albeit with some twists.

Figure 1.2 shows that in the least developed of the economies, Cambodia and Lao PDR, the governments have less engagement with digital technolgies than their global peers. On the other hand, the active agendas of the DGEIs for India, Malaysia, and South Korea reflect above-average government rankings. Asian economies tend to perform well in terms of government engagement, relative to other countries with similar GDP per capita.

The situation in the most developed economies is nuanced. Singapore performs particularly well in terms of government engagement on this index, both within Asia and also compared to the rest of the world. It achieves this through government action that actively invests in and promotes digital innovation. This is also the approach of others in the region—especially Malaysia—which see a vibrant digital economy as a key to unlocking greater productivity and lifting living standards.

Countries such as Japan have been pushing government-wide use of IT for more than a decade, and have created plans accordingly. At present, there is work going on for the promotion of initiatives such as the online use of administrative procedures, electronic provision of government information, optimisation of work and systems, improvement of government procurement related to information systems, and information security measures.1

In contrast, the approach of the Australian and New Zealand governments centres on supporting digital innovation mainly by keeping out of the way of market forces and avoiding over-regulation.

Like their governments, businesses in Asia have also generally embraced digital technologies more than their global counterparts for a given level of economic development (see figure 1.3). This observation, obviously, is not independent of the role being played by their governments as, for example, the broader environment in terms of regulation and the provision of infrastructure is crucial for businesses to be able to effectively use these technologies.

Nevertheless, the extent of business engagement depicted in figure 1.3 points to a competitive dynamic at play, with businesses considering it to be in their own interest to be leading edge if they are to survive in continually evolving and rapidly changing markets.

Success is breeding success.

In contrast to the results for government and business, consumers in Asia tend to be closer to the middle of the pack or even a little behind global counterparts (figure 1.4). In part, this is driven by a relative lack of access. Governments in the region are also conscious of this, specifically that the digital economy will need to develop in a way that is inclusive overall.

So the question to ask is: How is digital driving economic development?

Digital as a driver of economic advancement in Asia

Economic takeaways

- Asian countries are poised for development. Powered by digital, these countries have the opportunity to leapfrog development hurdles and make significant progress.

- Telephony and text are good platforms for consumers to drive change, but improved access and reduced device costs are inherent requirements for this to occur.

- Digital will have a greater impact on economies focused on services relative to resource-intensive economies.

- China is transitioning away from manufacturing and construction towards services, which will have an impact on its digital intensity.

As widely anticipated, Asia has assumed the mantle of being the centre of much of global economic growth in the 21st century. Countries have learned from each other and the momentum achieved across virtually all of eastern and southern Asia is set to continue. This would see the region account for a majority of the growth in the global economy over the coming decade.

Two core elements of the success of Asia’s economies over recent decades have been the opening of the traded goods sectors of their economies to market forces and the encouragement of the adoption of cutting edge technology wherever possible. These elements are related and have meant that these economies have been able to overcome hurdles to their development, bypassing old or second-best technologies and practices along the way.

Further, investment in digital infrastructure contributes to productivity in the same way as other forms of infrastructure. By boosting productivity and opening new channels of commerce, digital engagement ought to enhance economic growth beyond what would otherwise be the case.

Looking ahead, Asia’s engagement with digital technologies opens up even more opportunities to adopt best practices and technologies. For example, advances mean that:

- A fixed, copper-based telephony system will never need to be rolled out through many parts of India or Cambodia, or that

- Banking networks with physical outlets will not be needed to service the majority of Indonesia’s society that is currently unbanked.

In March 2017, Taiwan announced plans as part of its “Forward-Looking Infrastructure Construction Project” to invest US$ 1.5 billion over eight years to upgrade the country’s digital infrastructure. The investment includes improved access to broadband in regional areas, with a target of 90 percent broadband coverage nationwide.

The plans also include the development of a 5G mobile service network and an Internet of Things (IoT) network. These developments will help bridge the rural-urban divide and promote equal access.

Just how each country might embrace digital technologies to further its development goals will depend on the particular circumstances each country faces. The Deloitte engagement indices provide an indication of areas where different countries may focus their efforts.

Figure 1.5 shows how each of the countries ranks internationally across the three categories. In the less developed economies, there are opportunities for governments to take a stronger lead. In particular, Myanmar, Lao PDR, and Cambodia rank towards the bottom in all categories, and government action both in its own right and in support of business and consumers will be needed if they are to move up the rankings.

This situation contrasts with, say, Indonesia where the government ranking is high relative to its income. The chart does point to where there may be the greatest scope for improvement, namely individuals. And given the widespread use of mobile already in Indonesia for social interaction and basic commerce, there is a strong platform on which to build. This suggests greater opportunities as access to, and the price of, digital services improve.

Among the middle income economies, the contrast between Malaysia and Thailand is interesting. The Malaysian government has adopted a very proactive approach to the development of the digital economy. It has identified the technology sector as a driver of innovation and creativity. Through the Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation, the government seeks to promote inward investment in the technology sector and to support local technology businesses to compete in global markets. At the same time, the Malaysian government has also introduced initiatives designed to help individuals engaged as digital workers and entrepreneurs. The eRezeki and eUsahawan programmes were introduced in 2015 to provide both training and work opportunities to those interested in participating in the digital economy.

In contrast, government in Thailand has not been as aggressive in its adoption of digital in its own right, with business and consumers playing a relatively larger role. In Australia, the government has seen its role in the sharing economy as “getting out of the way,” that is, reduce regulatory barriers to innovation by business, rather than being actively involved in the development of the digital economy.

The Indian case is somewhat different; it’s a mixed approach, with the government and private players both pushing the digital agenda. One of the major initiatives by the Indian government has been to provide all residents with a unique identification code based on biometric data. The government is now using this vast digital identity library to significantly enhance the scope of e-government. This program is managed by UIDAI (Unique Identification Authority of India), which was established in 2009. This body has issued “Aadhar” cards to more than 1.1 billion people in India.

The usage of these cards has since evolved and increased, with benefits including greater efficiency in subsidy disbursals and helping targeting mechanisms for the government. Furthermore, the government has also recently unveiled a mobile phone-based payment system using the UID database of biometric identification.

While the government is keenly pushing the agenda of “digital India,” there have been notable successes in the e-commerce and fintech space, with at least 10 unicorns (billion US dollar valuation start-ups) as of the end of 2016 in India. These unicorns are encouraging integration across markets within the country as well as generating employment.

In drawing on some of these lessons, it is important to note that the composition of economies will have an impact on the potential role that digital technologies may play. In particular, digital technologies tend to be more important (relative to the total value-added of a sector) for sectors such as media, professional services, and finance, and relatively less important for parts of agriculture, mining, manufacturing, or trade.

To explore how important digital technologies may become for the different economies in Asia, we have developed an intensity map that reflects the existing industry composition of each economy.

Figure 1.6 maps the digital intensity of Asian economies against their NRI scores, based on their industry structure and the impact of digital on these industries. For countries such as Singapore, Japan, Australia, and, especially, Hong Kong, a large portion of the GDP comes from industries such as finance and information and communication. Therefore, the potential impact of digital is substantial.

By contrast, the economies of developed countries such as Vietnam, Cambodia, and Lao PDR are far more focused on industries such as agriculture, and as such, do not experience such an intense effect from digital disruption.

However, this means that as the less developed nations advance, digital may allow them to move through the stages of development more quickly. As they move to industries where digital has more of an impact, they will be able to benefit from the advances made by other countries and jump to the most up-to-date technology.

Of course, the economies in question are evolving rapidly. Figure 1.6 illustrates this for China, showing the path that China may take as its economy transitions to one relying more on the services sector.2 The economy is currently transitioning away from manufacturing and agriculture to services, with over half of GDP in China now coming from the services sector.3 As the impact of digital on the services sector is expected to be greater than that on resources, this transition will lead to an increase in the digital intensity of the Chinese economy.

Looking ahead: Keeping engagement front and centre

The Deloitte digital engagement indices highlight that Asian economies are leading the race. Across government, business, and consumers, Asian countries are more digitally engaged relative to global peers with similar levels of economic development. Singapore and Hong Kong are clearly the global leaders, but digital gives all economies the ability to overcome development hurdles. From online marketplaces to increasing participation in labour and financial markets, the digital world is their oyster.

This is all dependent on being digitally engaged. So, how engaged are you and how can you leverage digital as a government, a business, or a consumer?

Appendix A: Construction of the Deloitte indices

Engagement indices

The engagement indices are constructed from a range of existing indices and other publically available data. The full range of data sources include:

- The World Bank, “The ease of doing business,” 2016; in conjunction with PwC, “Paying taxes 2016: The global picture”; “World development indicators,” 2016.

- The World Economic Forum (WEF), “The Networked Readiness Index,” 2016; “The 2014/15 executive opinion survey.”

- The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “e-Government Development Index,” 2016.

- The Software Alliance, “The compliance gap: BSA global software survey,” 2014.

- The International Finance Corporation in conjunction with the World Bank, “Doing business 2015: Going beyond efficiency,” 2015.

- The International Telecommunication Union, “ITU world telecommunication/ICT indicators database, 2015.”

- UNESCO, “Tertiary education enrolment rates.”

- OECD, “Patent database”

- The IMF, “Financial access survey,” 2016.

- The Fletcher School, “Digital Evolution Index,” 2013.

Each index is comprised of several components coming from a combination of the above. In particular, the WEF’s Networked Readiness Index, the Fletcher School’s Digital Evolution Index, and the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Rankings were built into the indices.

Government engagement is made up of a combination of data profiling government use of digital technology, the extent to which they are creating a political and regulatory environment to foster digital development, as well as the quality of infrastructure established by the government to enable the use of digital.

Like government, business engagement is made up of business use of digital, but also includes measures of the business environment, for instance, innovation levels and start-up culture present in the economy.

Individual engagement is a compilation of usage measures (for example, mobile phone subscriptions, households with Internet access, and so on), as well as a demographic profile of individuals in the economy (for instance, education and income levels of the population).

Digital Intensity Index

The digital intensity map was constructed by examining the extent to which digital advances will impact an economy industry by industry. Each industry was then weighted by the extent to which digital would have an impact (for instance, impact of digital on finance and communication is larger than on agriculture and manufacturing). Data for these industry weightings come from the Deloitte Access Economics report: Digital disruption: Short fuse, big bang?

Asian countries were then assigned these weights in proportion to the industry makeup of their GDP (from UN data). The result being an “intensity” score for each nation—with those countries with a higher focus on industries set to be disrupted by digital scoring higher.

Future China was derived by reweighting current industry shares of GDP to a more services-focused economy, and then recalculating digital intensity assuming those shares.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.