Psychological barriers to the elevated future of mobility Are consumers ready to take to the skies?

26 November 2018

Engineers are making flying-car dreams come true. But for aerial passenger vehicles to become part of the new mobility ecosystem, creators and operators must convince skeptical consumers that airborne drones are both useful and safe.

Introduction: We were promised flying cars

Would you climb into an air taxi? The question isn’t purely speculative: In a previous article, Elevating the future of mobility, we discussed how passenger-bearing vertical takeoff and landing vehicles are expected to soon expand transportation into new modes.1 Creators intend to make urban science fiction a reality, reducing hourlong commutes to minutes in the air, improving productivity, reducing pollution, and improving the overall quality of life by replacing at least some driving in cities around the globe with autonomous aerial passenger vehicles.

Engineers have long worked on solving technological problems: For such aircraft to be viable, they would seemingly need to accommodate two to five passengers, be energy-efficient, and be far quieter than a traditional helicopter. It’s a tall order. But ultimately, the biggest barrier to the elevated future of mobility likely isn’t technological—it’s psychological.

In short, most consumers are skeptical of the idea of travel in these new short-range autonomous airborne vehicles, even after 90 years of onscreen portrayals—beginning with 1927’s Metropolis—to get them used to the idea.2 This shouldn’t surprise anyone—people have always hesitated to be the first to climb aboard new forms of transportation, whether hot air balloons, steam trains, gas-powered automobiles, prop planes, or self-driving cars. And to consumers, aerial vehicles seem, understandably, more inherently hazardous than earthbound vehicles.

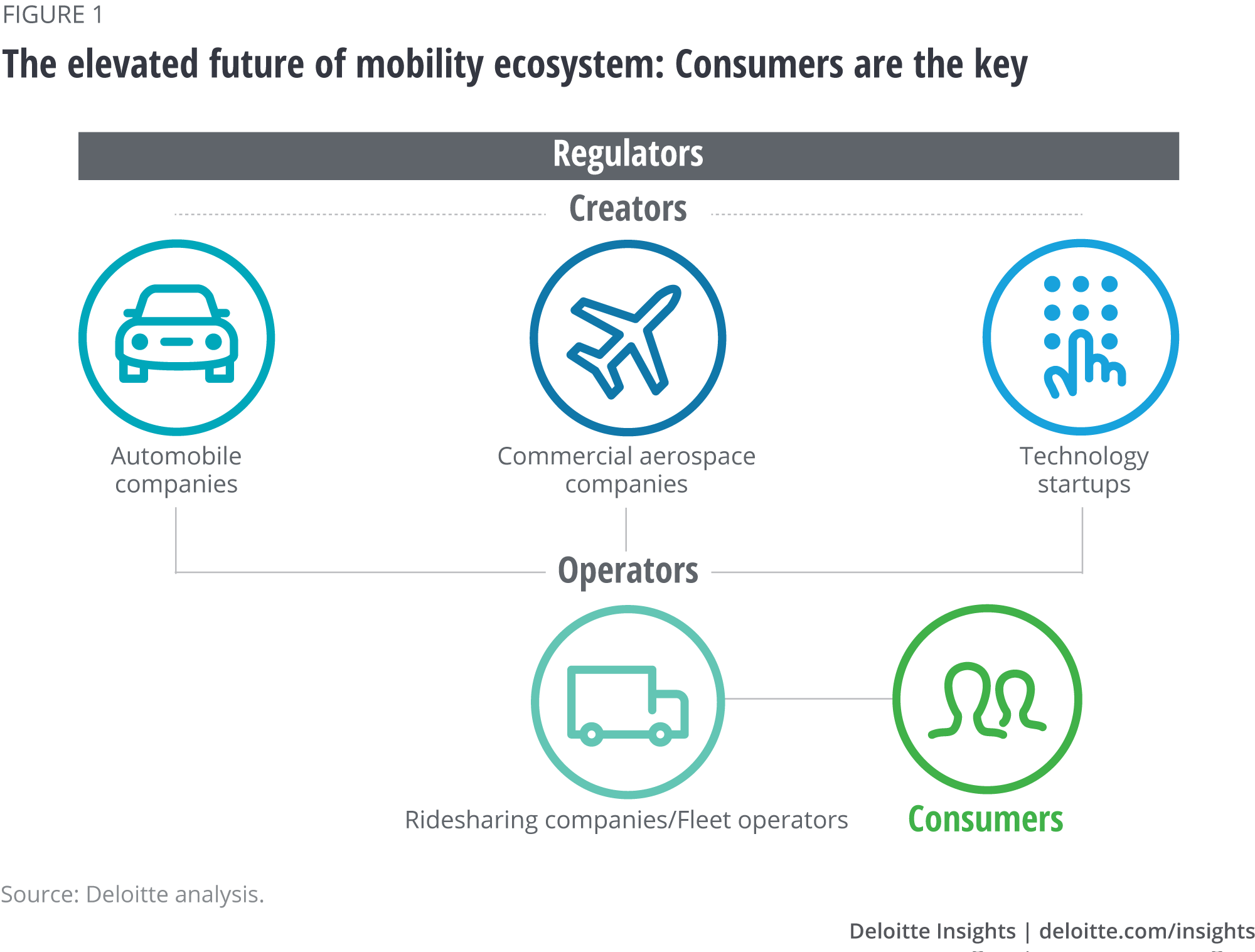

That skepticism is as big a challenge for operators of next-generation aerial passenger vehicles as the technology is for engineers. Without broad popular acceptance of the idea, the elevated future of mobility may never get off the ground, and quadcopter cars could be relegated to entertainment for affluent hobbyists.3 Shaping consumer attitudes will likely be the joint responsibility of regulators, creators, and operators of these new aerial systems. People will need to feel confident that the vehicles are safe, reliable, and predictable—and that they’re actually improving society.

First, it’s key to understand consumers’ current attitudes toward these vehicles—and what key stakeholders can do to transform consumer perceptions and eventually make taking to the sky a part of commuters’ and travelers’ daily lives. To measure the dimensions of psychological barriers, Deloitte conducted a global survey this year, asking consumers about their perception of autonomous aerial passenger vehicles, with respect to their safety and perceived utility—two barriers to the acceptance of these vehicles of the future.

At the core of the elevated ecosystem: Consumers

Regulators, creators, and operators all have critical roles to play to make the elevated future of mobility ecosystem commercially viable. (See figure 1.) But the entire ecosystem revolves around the consumer: Unless ordinary people embrace this next-generation mode of transportation—incorporating airborne options into their daily lives along with more traditional modes—cars will likely stay earthbound. Passengers would need to feel as though aerial vehicles are, at least sometimes, the best way to get them where they want to go.

Operators’ role will be vital in the embryonic stages. Even with much still speculative, the pattern of initial adoption will almost certainly not follow that of the venerable automobile industry, which began by emphasizing an ownership model and introduced operators at a much later stage. In setting up a strictly autonomous system without a private-ownership option—meaning no freelance drivers zipping by above city streets—operators could help aerial passenger vehicles find a market in the early stages by emphasizing affordable access.

Skeptical about safety

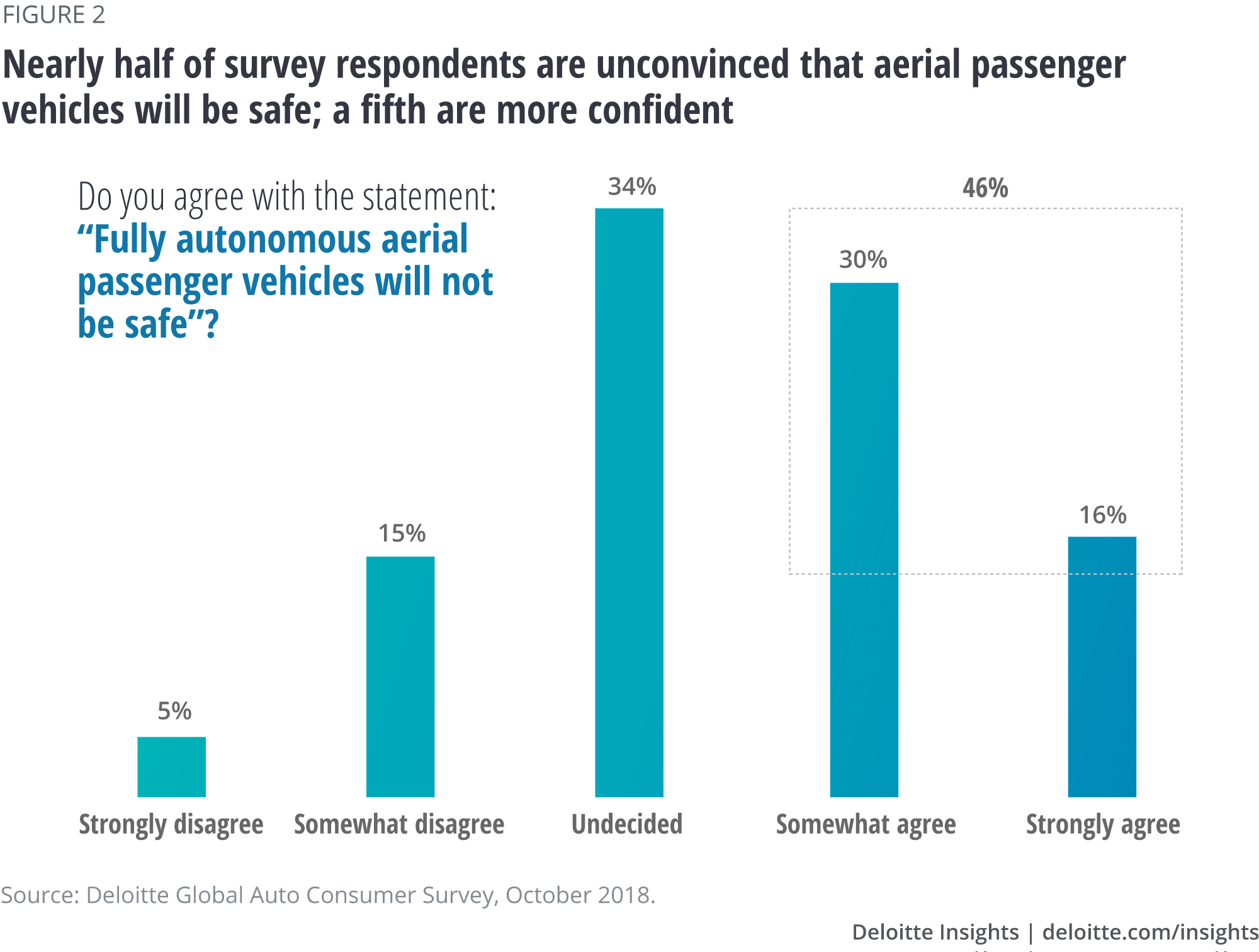

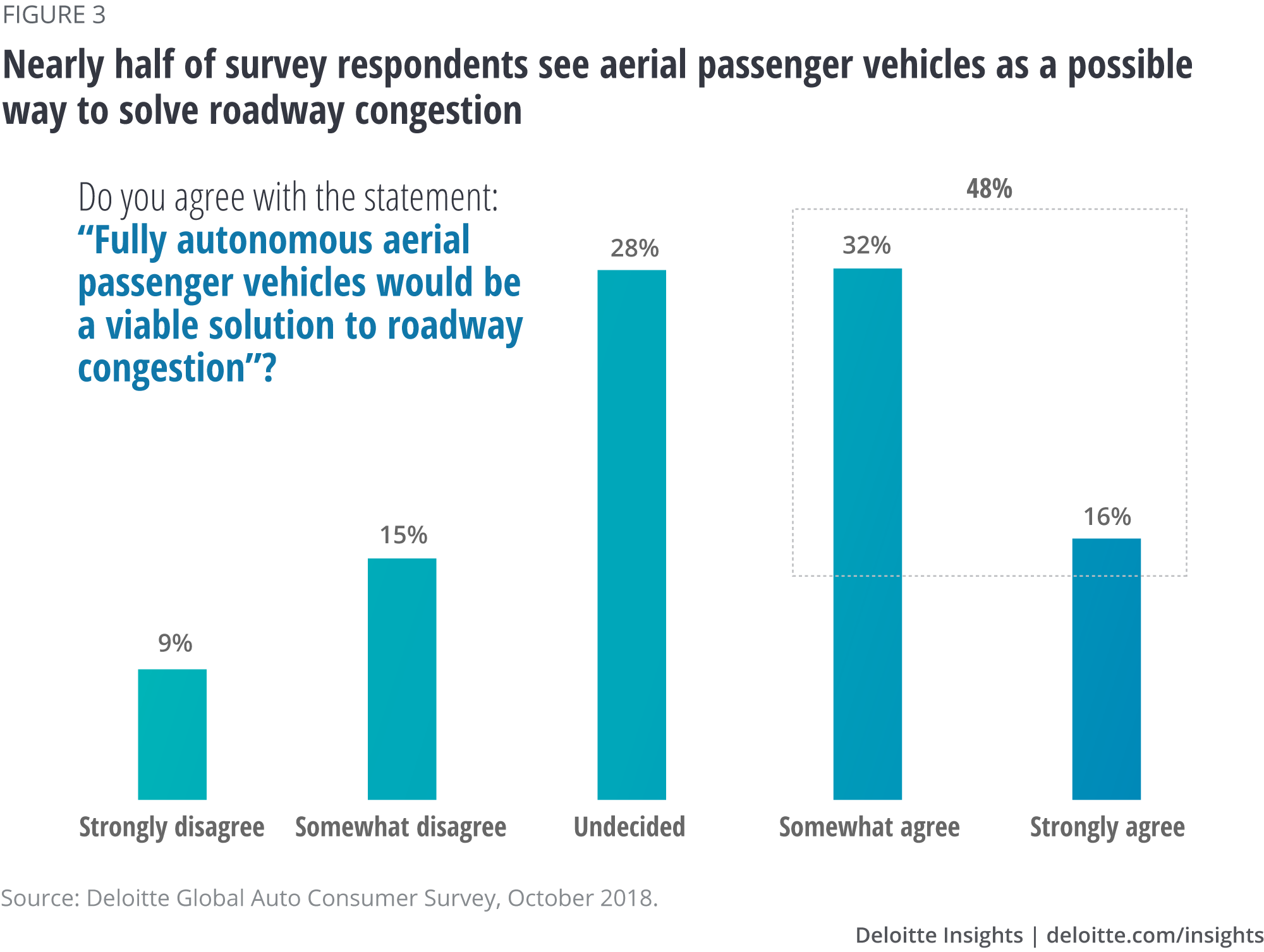

In a recent global survey, Deloitte asked consumers a series of questions about their perception of autonomous aerial passenger vehicles, with respect to these vehicles’ safety and perceived utility. The sample size for the survey was 10,300; regions covered include the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, France, China, Japan, and Australia. The results suggest that many consumers, even now, see clear utility in next-generation aerial passenger vehicles but—unsurprisingly at this point—seem to harbor serious concerns about their safety.

Globally, nearly half of the survey respondents view autonomous aerial passenger vehicles as a potentially viable solution to roadway congestion. But initial impressions show how far operators need to go: 80 percent of the total respondents either believe that these vehicles “will not be safe” or are currently uncertain that they will be safe. (See figure 2.)

Responses across national borders were comparatively consistent, though Japanese respondents expressed particularly high safety concerns, with 87 percent of consumers seeing autonomous aerial passenger vehicles as unsafe or remaining undecided, while only 73 percent of Chinese consumers agreed with that assessment. In the United States and United Kingdom, 79 percent and 83 percent, respectively, expressed the same apprehension regarding safety.

Country differences emerged far more clearly on the question of whether people can readily envision such vehicles helping to alleviate roadway congestion: In China, almost three-quarters of respondents expressed enthusiasm, while only 44 percent and 38 percent of US and Japanese respondents agreed.

Driving future adoption demands changing consumer perceptions

How to boost consumer confidence in the elevated future of mobility? In short, the industry should focus on changing perceptions of the safety and utility of autonomous aerial passenger vehicles. And considering the mental leap necessary for millions of passengers to feel safe climbing into a flying car, the challenge shouldn’t be understated: Changing consumer attitudes is expected to require a significant effort by every ecosystem stakeholder—regulators, creators, and operators. There’s already plenty of consumer apprehension around the safety of self-driving cars,4 and once those cars leave the ground and begin competing for airspace with recreational drones, package delivery drones, and larger autonomous aerial cargo vehicles—as well as existing objects and infrastructure—passengers will likely need that much more reassurance that it is safe to take to the skies.

Some steps that stakeholders can consider:

Regulators

- Follow a stringent certification process to ensure that these vehicles are at least as safe as a piloted commercial aircraft.

- Focus on creating a robust traffic management system for autonomous aerial vehicles—and integrating it with existing systems.5

Creators

- Equip these vehicles with enhanced safety equipment such as advanced detect and avoid sensors6 as well as safe emergency landing systems to help assure consumers of their safety.

- Demonstrate high levels of reliability and safety margins on all vehicle components.

Operators

- While developing and introducing services, maintain a zero-tolerance stance on safety, since any accident could set back consumer attitudes by months or years.

- As operators will collaborate with manufacturers to increase these vehicles’ market reach, they should create more consumer awareness of their safety and utility.

Conclusion: The importance of social acceptance

This next era of elevated mobility, one in which we might well see autonomous aerial passenger vehicles soaring past high-rise office windows, has a lot to learn from the aviation industry—particularly, how airlines and government agencies built social acceptance of aircraft as a new mode of transportation, back in the early 20th century. To help instill public confidence in an era of barnstorming and daredevils, the American aviation industry lobbied the federal government to create safety regulations, resulting in the 1926 Air Commerce Act.7

Today, aviation is one of the safest modes of transportation, with a fatal accident rate of only one per 16 million large commercial passenger flights.8 Most of those incidents take place during takeoffs and landings, where there is most human intervention, and safety has improved as automatic systems have taken over more of the entire process.9 Players in the new mobility ecosystem are counting on consumers’ eventual comfort with self-driving cars—and perhaps that would help people feel safer when operators introduce autonomous aerial passenger vehicles as an option for commuters or daytrippers.

Less human involvement means fewer overall safety concerns. At least, that’s what it should mean, as advocates of self-driving cars well know.10 It will take more than a few reassuring TV ads to convince millions of passengers to climb into autonomous aerial vehicles. But as public confidence in both air and road travel illustrates, the elevated future of mobility seems within reach.

Explore the Future of Mobility

-

Forces of change: The future of mobility Article6 years ago

-

The future of parking Article6 years ago

-

Seleta Reynolds aims to bring 21st-century mobility to a city built for cars Article6 years ago

-

Elevating the future of mobility Article6 years ago

-

The future of mobility for the media and entertainment industry Article7 years ago