Shaping the future: Delivering on the promise of Indian higher education Insights from the 2019 Deloitte Deans’ Summit

9 minute read

13 August 2019

India has the demographic edge: a young talent pool that is estimated to become the world’s largest by 2030. But is the higher education sector up to the challenge? Here’s a look at the issues the sector faces and some solutions.

India’s higher education sector has supplied some of the world’s best talent. The CEOs of some of the biggest Fortune 500 companies—Microsoft, Google, Mastercard, and Adobe—are a product of the Indian higher education system. The landscape has also expanded over the past decade—from 436 universities in 2009–10 to 903 in 2017–18 and from 26,000 colleges to over 39,000.1 Student enrolment, at 36.6 million, is the third-largest in the world, next to China and the United States.2

Learn more

Explore the Future of higher education in India collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

Besides, India is already in the middle of the “demographic dividend” with a surge in its younger and working-age population, which is estimated to become the world’s largest by 2030.3 India is expected to account for about 20 percent of the total young talent pool supplied by the non–Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) G-20 countries.4 Given this scenario, India’s higher education sector will continue to play a critical role in driving the nation’s talent competitiveness.

However, global forces of change—the rise of artificial intelligence (AI), the fourth industrial revolution, the future of work—are disrupting the ways in which we learn and work. For instance, there is a growing debate about the impact of AI and automation on jobs, shelf-life of skills, and changing learning models in the digital era. Other factors, such as the growing cost of education, funding constraints, and the rise of nontraditional ways of learning, are altering the education landscape globally. Add to this the growing challenge of the skills gap across sectors, which has made it imperative to align learning with the industry demands.

The Indian higher education sector is at a critical juncture; it needs to prepare well for such disruptions. This article will focus on some of the key challenges faced by the Indian higher education sector, including the quality of research, matching market demands, lack of funding alternatives, and attracting and retaining high-quality faculty. Moreover, the study will discuss broad strategies such as developing an educational ecosystem, evolving learner-oriented curriculum, and driving efficiencies in the current educational system to deliver best-in-class talent and support a growing economy.

Understanding the Indian higher education sector

In April 2019, Deloitte conducted a Deans Summit, attended by deans, directors, principals (all will be referred to as deans in this article) of 63 top-tier institutes in India. The deans from various institutions—including business, engineering, and other undergraduate schools—took a deep dive into the challenges faced by the higher education sector and discussed ways to address them. In addition to the deans’ roundtable discussion, Deloitte surveyed the 63 deans, more than 900 alumni, and over 3,000 current students from these institutions. The insights gathered from the Solutions Lab and the survey have been captured in a series of four articles covering the following topics:

- Future of higher education

- Future skills of educators

- Reengaging alumni

- Future of work

This article focuses on the “future of Indian higher education” and is a culmination of research, conversations with the deans, and a survey of different stakeholders in the higher education market.

Key challenges impeding the performance of the higher education sector

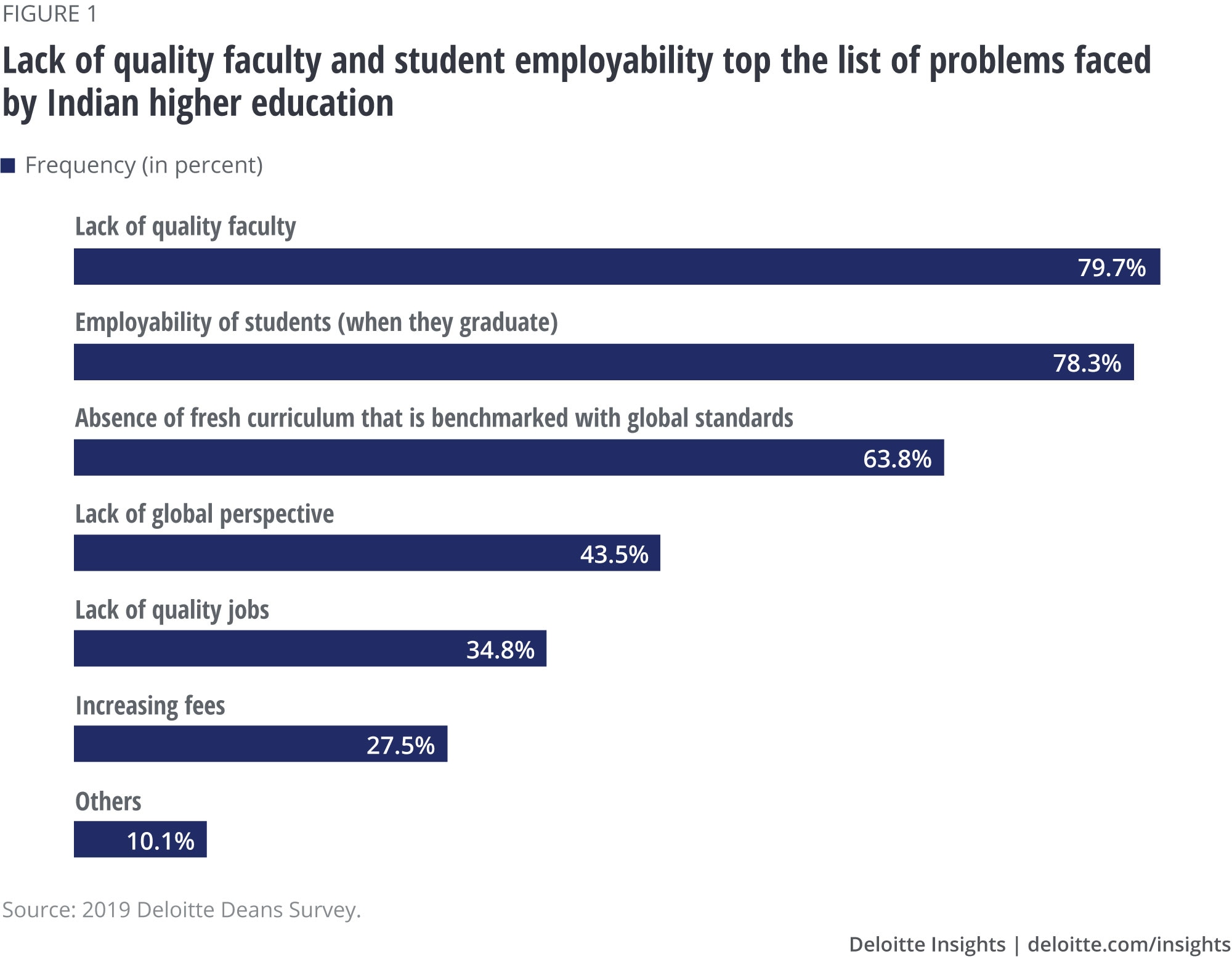

While Indian higher education has grown tremendously in terms of enrollment, some areas still need attention. Challenges include gaps between the skills being imparted and the skills needed at the workplace, skill gaps among faculty, a paucity of funding channels, and the amount and quality of research being carried out in these institutions (see figure 1).

The growing divergence between curricula and market demands

In the postindustrial era, the skill sets one obtained in college or university served one for a lifetime—an engineer who picked up his skills in college could hope to tap into them throughout his career. However, over time, the shelf life of skills has declined. Educational institutions, unfortunately, have not kept up with these changes. Sixty-four percent of the deans in our survey think that the absence of a fresh curriculum is a challenge for the Indian higher education system.

The growing gap between college curricula and market demands is a major challenge for the higher education sector today and has led to a widening skills gap in the talent entering the market.5 For instance, next to China, India is the largest producer of STEM graduates—2.6 million in 2016 versus China’s 4.7 million.6 However, according to the India skills report in 2019, only 47 percent of the available talent is employable.7 This is reflected in the 2019 Deloitte Deans Survey: Only 28 percent of the deans believe that their students are industry-ready.

The quantity and quality of research

There is much debate about the quantity and quality of research around the world. One view is that the extensive research published globally is putting tremendous pressure on the peer-review system, which in turn affects quality. Besides, many people question the value of research papers that are not freely available for everyone to read: Only 25 percent of global research is available through open access platforms and without a subscription.8

However, despite these drawbacks, research—as measured by the number of publications, number of citations, citation per document, and the H index9—remains one of the factors that determine the quality of higher education. Deans identified the quality of research in India as a big challenge during the Solutions Lab.

The importance of research in education, especially higher education, can be traced back to the 19th-century Humboldtian model of education in Germany, which proposed research as a core component of university studies. Since then, the quantity of research has improved. According to some estimates, more than 30,000 scientific journals are publishing over 2 million articles every year globally.10 The number of publications from India has steadily increased over the years, but it still lags leading countries such as the United States, China, United Kingdom, and Germany. The same is true for the H index of faculty and researchers in India.

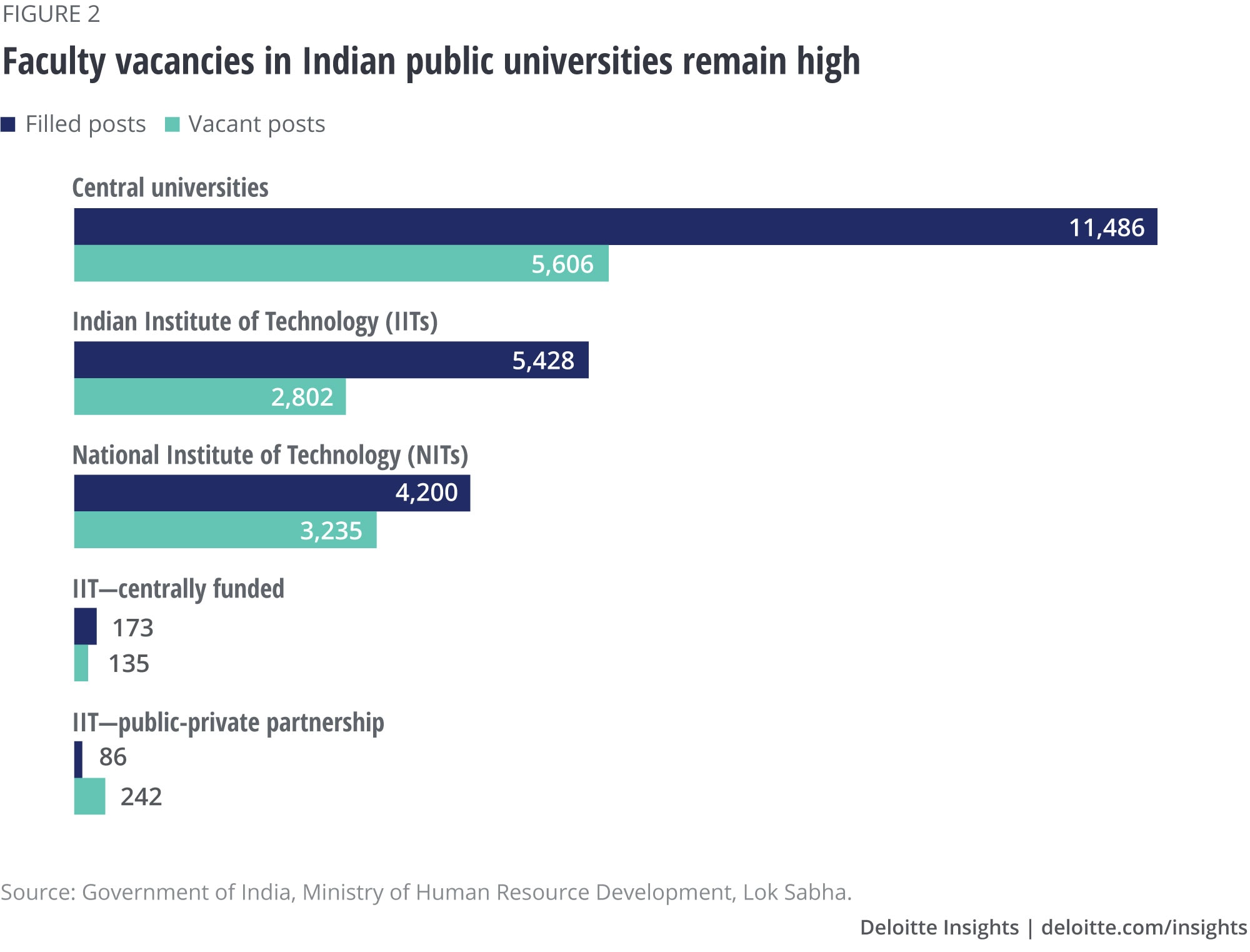

Faculty vacancies and skills gap could dampen the quality of education

Faculty vacancies in public higher education remain high (see figure 2).11 According to the dean of an undergraduate college, “The current lot of permanent faculty is inadequate. There are about 19–20 open positions in my institute, of which only 5–6 have been appointed.”12

Not only the students’ but even the faculty’s skill sets are not in tandem with the needs of the institutions. Nearly 80 percent of deans in our survey say that lack of quality faculty is the biggest challenge for the Indian higher education sector. More than 90 percent believe that the faculty needs to upskill more than once a year to match industry expectations. According to the dean of an engineering institute, professors in the engineering schools need to be trained by specialized institutes to bring the latest thinking to the classroom—train the trainer.13

While acknowledging the need for more research, deans also call for a balance between research and teaching. There is a need to identify which faculty member can drive research and who can facilitate teaching at institutions.

Lack of funding alternatives

The quality of research is also a function of adequate sources of funding. Insufficient funding was another top concern identified by most engineering and business school deans during the Solutions Lab. As one of them said, “The decline in public funding, coupled with a lack of the corresponding rise in tuition fees, has put pressure on the current education system.”14

The numbers also show that public funding for higher education has stagnated. In 2015, India’s expenditure on research stood at 0.62 percent of GDP versus China’s 2.06 percent.15 Public funding for education remained at around 3 percent of GDP in the past five years against 6 percent for other developing nations such as Brazil and South Africa.16 The Draft National Education Policy (NEP) 2019, however, offers hope, with a proposal to increase public investment in education to 6 percent of GDP.17

Structural and learning reforms needed to become truly best in class

The Indian education landscape is in the process of transforming into a more targeted, learner-oriented model. Moving ahead, it will be crucial to design innovative solutions to accelerate the performance of the higher education sector to meet market demands, improve access to students, and drive efficiencies in operations.

Create a broader education ecosystem

Currently, the various components of higher education—educational institutions, students, alumni, regulatory and accreditation agencies, employers, and governments—operate in silos, resulting in barriers for students.

There is a need for a broader education ecosystem; ideally, one that goes beyond the university and includes industry, government, regulatory agencies, and think tanks. Globally, partnerships do exist between industry and higher education. For instance, Arizona State University’s (ASU) “InStride” initiative helps businesses provide their employees with university learning and degrees from global institutions.18 The for-profit program, in which a private equity fund has a majority stake, addresses two important issues for the broader ecosystem:

- It allows employers to educate and reskill their employees continuously.

- It tackles the funding issue by generating funding through a private equity fund.

Institutions can explore a “Partnership University” model where businesses and other employersemployers—such as the government, research institutions, and think tanks—help the institution in preparing talent for the knowledge economy. For instance, businesses can provide insights on curricula, financial assistance for equipment, and other essential resources.19 Institutions can partner with employers to include apprenticeships and internships in the curriculum that provide the same amount of credits as a course.

However, creating such an ecosystem is not easy and calls for immense coordination. Moreover, the government, as well as the regulator, will have to build the necessary framework. Policies proposed in India’s Draft NEP in 2019 show promise in this direction. For instance, it calls for a single regulator and a rigorous accreditation process for the entire higher education system.20

Strike a balance between learning and job-readiness

According to the dean of a B-school, “People are more concerned with getting a job on the very first day of the placement season rather than looking at whether the job offered will lead to a sustainable career ahead.”21 This is a contentious issue in today’s educational system across the globe. Students, who put in four years of learning, are, after all, justified in expecting to be employed at the end of it. On the other hand, a sole focus on employment could diminish the focus on learning. What’s needed is a balance between the two schools of thought.

Universities need to strike a balance between learning and employment opportunities. One way to approach this is to integrate some of the key employment skills—such as problem solving, critical thinking, communication, and entrepreneurial abilities—into the curriculum. Not only will this help shift the focus to practical methods of learning but it can also ensure a relatively smooth transition to employment.

Besides, the profiles of those accessing Indian higher education have evolved over the years to include not just traditional students, but also employees and other adult learners. Education and learning need to center around the preferences of the learners, and this calls for migration from traditional modes of learning.

Educational institutions can explore an “Experiential University” model where students alternate between classroom learning and work related to their field of study. It allows both employers and students to evaluate fit before committing to a full-time position.22

Promote interdisciplinary learning

Today’s learner is not content with a constricted education model and wants to mix and match disciplines. The onus of executing this is mostly on the universities (and on the regulator). Interestingly, some states such as Maharashtra have already moved in this direction. For instance, Dr. Homi Bhabha State University (HBSU) has created the state’s first cluster university that will provide students access to subjects across disciplines and campuses from 2019.23

There is a need to move beyond the system of rote learning and facilitate students in choosing their own learning paths. Such interdisciplinary learning can help students broaden their knowledge beyond a single domain.

Expand online education

Virtual modes of learning are popular across the world. India’s e-learning market is likely to expand to over 9.5 million users by 2021.24 Building a credit-system for such learning will be important to encourage students to leverage these courses as part of their overall education. For instance, the Ministry of Human Resource Development’s (MHRD) SWAYAM offers free online courses,25 which allow students to continue “life-long learning” and help them to reskill and upskill.

Institutions can explore the “Subscription University” model where the institution becomes a platform for continual learning for both technical and soft skills—throughout a student’s lifetime. Students walk in and out of the system to gain and update their knowledge and skills by paying an annual subscription fee.26

Improve funding and cut costs

While developing a viable ecosystem will likely plug some of the gaps in funding and research quality, the Indian higher education sector needs a systemic reform as well. Take, for example, the lack of funding for research, a huge constraint for educational institutions. Public funding for research is available mostly to public universities—and just a handful of private institutions.27 As one dean of an undergraduate school put it, “Promote a system of rewards to promote a culture of research and conditional sabbaticals for research purposes. Explore ways to look for a donor, maybe alumni, to sponsor such programs.”28

The Indian higher education sector can also experiment with performance-based funding models that drive funding based on parameters such as retention rates, graduation rates, research output, or even global student exchange. For instance, in Denmark, funding for institutions is partly based on students’ graduation rate.29

In addition to innovative funding models, there should be efforts to cut costs. Institutions can explore a “Sharing University” model that allows sharing of repetitive activities with other institutions to leverage individual institutions’ strengths. Some of the shared services include career services, centralized marketing function, and admissions.30 The emergence of the Cluster University model discussed earlier is the right step toward sharing resources across institutions.

Conclusion

The Indian higher education sector is at a crossroads. Students want skills that can help them thrive in the market and employers desire talent that can match and evolve based on market demands. However, the gap between talent demand and supply persists. This is primarily because educational institutions continue to operate in silos, and there is no formal ecosystem in which employers can regularly engage with students as well as faculty.

The digital-age education system calls for personalized and dynamic methods of learning, a better-equipped faculty, new parameters to gauge student and faculty performance, and innovative models of funding. A broader and a more collaborative coalition among educational institutes, employers, students, professionals, regulators, and government entities can help plug the existing gaps and drive reforms in the Indian higher education sector.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more on higher education

-

The Reimagine Learning network: Tackling persistent problems Article5 years ago

-

3D opportunity for higher education Article5 years ago

-

How government and business can team up to reskill workers Article6 years ago

-

Student success by design Article6 years ago

-

Understanding workers' expectations in Europe Article6 years ago

-

Future of public higher education Article6 years ago