Horizon next A future look at the trends

15 minutes

15 January 2020

How can organizations see beyond what's new to what's next? A disciplined innovation program—aligned with business strategy and a long-term technology landscape—can help leaders chart a path to the next horizon.

“The best way to predict the future is to create it.” Peter Drucker’s well-worn adage contains at least two distinct ideas. The first: that initiative and determination trump passivity and idle speculation. The second? The notion that prediction is itself a fool’s errand because the future is essentially opaque and unknowable.

Learn more

Listen to the What's next? A future look at the tech trends podcast

View Tech Trends 2020

Download the Executive summary PDF

Watch the video

Go straight to smart. Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

But as we discussed in Tech Trends 2019, if you can be deliberate about sensing and evaluating emerging technologies, you can make the unknown knowable. The principled consideration of tomorrow can be a profoundly useful tool in guiding today’s business and technology decisions. Using a traditional one-to-two-year budgetary lens, a company might be inclined to incrementally adjust last year’s budget by factoring in next year’s forecast. A longer view challenges us to rethink this approach and make entirely new bets. Disciplined futurism can help us avoid overindexing on the past.

There’s an inherent tension in planning for the horizon beyond. While the full potential of the technologies explored in this chapter may not become clear for several more years, there are relevant capabilities and applications emerging now that can provide a foundation for what’s coming next. If you wait several years before thinking seriously about them, you may have to wait three to five years beyond that for your first nonaccidental gain. Because these forces are developing at an atypical, nonlinear pace, the longer you wait to begin exploring them, the further your organization may fall behind.

Prospection, not just prediction

Prediction is useful, but it is only one of the modes of thinking we employ when factoring for the future. A more appropriate umbrella term is prospecting. Futurists acknowledge that there are many prospective futures, and that organizations would be wise to actively maintain a “matrix of maybes”—an inventory of not-ready-for-prime-time technology prospects that may (or may never) drive widespread business impact.

This process of sensing, scouting, and scanning can help expand apertures for what is looming beyond the horizon, and for when and by whom. This last point is important. Companies can challenge “not invented here” organizational bias by embracing ecosystems of new players that can help make strategies real. It will no longer matter if the necessary talent and technology is built, borrowed, or bought. Armed with numerous à la carte prospects as an input, leaders can use research-based methods to determine which prospects are viable.

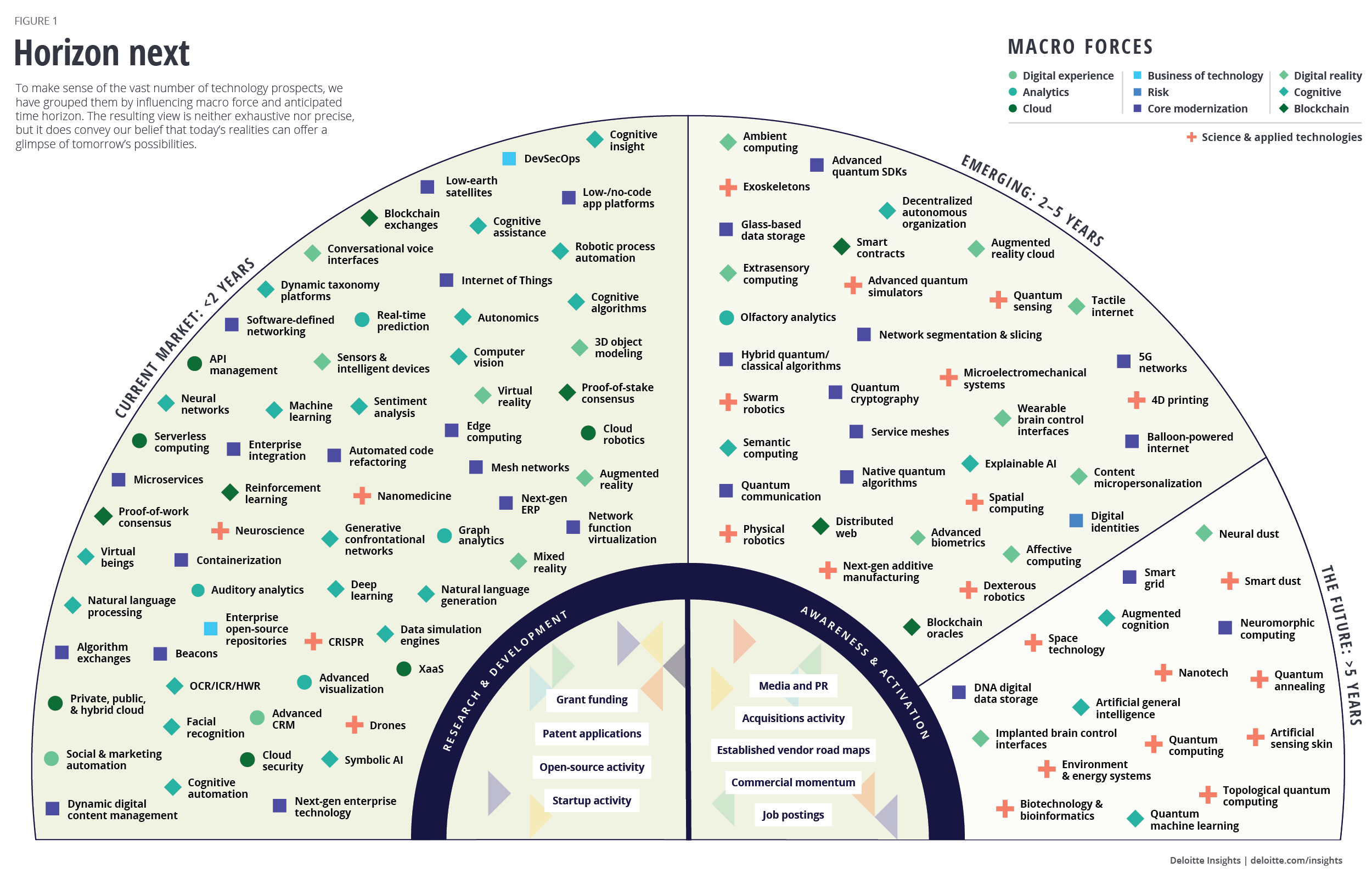

Research and development

Signals that can alert you to what’s happening in R&D come from several sources. Tracking activity over time can help triangulate investment, solution maturity, and patterns of advancement. A deeper understanding of each can give you the confidence you’ll need to tackle the hardest piece of the equation: timing any investment. Sources of intel include:

- Grant funding provides a window into prospects’ earliest momentum. Because transformational technologies are often born in academic and lab environments, a periodic pulse check on grant awards can help you learn more about individual initiatives and macro movements.

- Patent applications begin to spin off as concepts mature from ideas to inventions. Patent filings and awards, which are matters of public record, provide not only detailed visibility into what technologies are coming of age but, critically, how they are being designed and architected.

- Open-source activity is another helpful R&D lens. Twenty years ago, high-value software was largely a heavily guarded trade secret. Many of today’s emerging technologies are created out in the open, by collaborative amateurs and professionals.1 By studying open-source software trends, you can begin to detect those technology prospects that have the most gravitas and momentum.

- Startup activity and venture capital inflows can provide insights into the early inklings of a concept’s financial viability. By further monitoring startups’ commercial traction, you can begin to understand directional product-market-fit. In short, you can bear witness to a concept’s graduation from an experimental technology to a sustainable business model.

Awareness and activation

The first collection of signals track money and invention. The signals below are equally important, representing traction and growing impact across enterprises as they mature and are deployed in the world.

- Acquisitions activity tells the story of an emerging concept’s breakthrough from disruptive outsider to constructive insider. While any individual M&A deal may distract with gaudy financials or a curious strategic rationale, the landscape view is typically telling.

- Media and PR are also a “tell.” As accelerating technologies turn the corner from hope to hype, media research and sentiment analysis quantify the buzz, shining a light on new entrants’ marketability and virality. Some skepticism here is warranted, as hype cycles can distract and disguise barriers to investment.

- Established vendor road maps mark an organization’s enthusiasm for, and commitment to, a new technology. As organizations transition from PR and media campaigns to budgeted investment in strategy, processes, and people, the pivot from talk to walk begins in earnest.

- Commercial momentum formalizes an emerging technology’s coming of age. Whereas the aforementioned lenses are inherently supply-side in nature, commercial transactions, at scale, denote quantifiable market demand. These can be told via press releases, vendor case studies, keynotes, and even sometimes earnings reports.

- Job postings can be the final proof point for accelerating maturity. From salaried job openings to increases in demand on crowdsourcing marketplaces, expressed need for talent aligned to a given topic or technology is a great proxy for growing mindshare and investment.

Horizon next

To make sense of the vast number of technology prospects, there’s a clear need for a unified view organized by both the macro technology forces and by their anticipated time horizon. The construct in figure 1 is neither exhaustive nor precise. But it does convey our confidence that in a world of uncertain futures, it is possible to bring order to and focus attention on a meaningful collection of known technologies that can help you shape your ambitions, focus your investments, and chart a path to tomorrow.

Patterns between signals

Sensing, scouting, and scanning across horizons are techniques meant to help make the future more navigable. At the very least, they can define the playing field of potentialities. Unfortunately, the reality of the volume of concurrent advances and the accelerating pace of change can have the opposite effect: They can seem overwhelming while stoking cynicism, undermining the confidence of companies pursuing emerging tech. With so much going on, how can you possibly decide what matters, much less what to do about it?

Luckily, many of the individual technologies noted earlier are themselves building blocks of larger categories of change that have the benefit of being less volatile, more easily understood, and having clearer applications to one’s business or mission. The macro forces construct—enablers, disruptors, foundation, and horizon next—introduced in the macro technology forces chapter is an attempt to distill decades of technological change into a set of manageable clusters. Besides being more digestible, they remain relevant for longer periods of time, allowing momentum to build externally—consolidation of ecosystems, maturation of product and solution offerings, increased and increasingly insightful coverage by analysts and the media—and internally, with concrete examples of positive impact leading to growing investment appetite and positive word of mouth across the organization.

This is no ontological shell game. For most business and IT executives, the piece-parts that can lead to significant technology breakthroughs aren’t just ungainly—they’re incomprehensible. Much like traditional R&D and scientific labs, the combinations of underlying technology lend themselves to applications and products for the broader market. Looking forward is necessary, and some of the individual advances will no doubt lead to bold new thinking. That said, these broader categories will likely represent the biggest bang for the emerging technology buck.

Macro forces revisited

The macro technology forces have evolved over Deloitte’s 11 years of technology trends research. With our eyes on the next horizon, we’ll do a quick deconstruction of ambient experience, exponential intelligence, and quantum to look at today’s building blocks as we wait for technology advances required to realize the full vision.

But first, let’s apply this thinking to a more established, familiar concept such as cloud. In our first Tech Trends report in 2010, much of the dialogue with our clients focused on cloud’s definition, its potential impact, and its projected expanded role in enterprises. Seasoned CIOs were dismissive of the concept, arguing that it seemed like some old mainframe concepts being repackaged. The response 11 years ago is the same as today’s response: Those naysayers were not technically wrong, but neither was their thinking complete. Cloud is absolutely an evolution of essential mainframe concepts, from logical partitioning to distributed storage to virtualization. It also represents advances in standardized data transmission, network protocols, grid computing, multitenant resource pooling, identity and access management, dynamic provisioning, measured services (the ability to meter, bill for, monitor, and control underlying resources), and more, at scales historically unimaginable, at price points that would have been unthinkable, and with an unprecedented road map of expanding capabilities up, down, and across the technology stack. Choose your metaphor: “Cloud” is the meal made from these individual ingredients, the symphony for these instruments, the molecule for the atoms.

The most important fact is this: The focus has moved from conversations about what’s under the hood toward investments in the composite driving real business impact. The same is happening for the other macro forces at the horizon now and next and will, eventually, happen for those at the horizon beyond.

Each of the macro forces and the broader inventory of emerging technologies will mean different things to different industries and geographies. But one thing is universal: None of these individual technologies comprises a strategy. Balancing the maturing of each individual technology with the need to project potential business use cases as they come together is where the action is. It is also nearly impossible to do without an intentional, structured approach to sensing and incubation.

Path to tomorrow

Ambient experience, exponential intelligence, and quantum are the nascent macro forces we currently see on the distant horizon. Like cloud technologies before them, they will evolve over time and perhaps cross-pollinate with other forces to create something wholly new. For each, here’s a quick exploration of where they’re heading, and a snapshot of some of the technology breadcrumbs helping build toward that potential.

Ambient experience. Represents a world where the physical and the digital are intertwined with such elegance and simplicity that we shift to natural, intuitive, and increasingly subconscious (maybe even unconscious!) ways of engaging with complex technologies.

- Machine-to-machine interfaces

- Internet of Things

- “Smart” devices

- Computer vision

- Intelligent conversational interfaces

- Beacons

- 5G

- Edge computing

- 3D object modeling

- Spatial computing

- Dynamic digital content management

- Digital identities

- Brain-computer interfaces

- Extrasensory computing

Exponential intelligence. General-purpose superintelligence able to build algorithms, confident predictions, and automated responses across complex, dynamic, and constantly evolving domains.

- Deep learning

- Neural networks

- Symbolic AI

- Reinforcement learning

- Generative confrontational networks

- Semantic computing

- Advanced data management

- Advanced visualization

- Data simulation engines

- Cognitive assistance

- Autonomics

- Algorithm exchanges

- Dynamic taxonomy platforms

- Quantum algorithms

Quantum. Evolution of computing to harness the power of quantum dynamics to dramatically unlock new workloads and insights.

- Advanced quantum SDKs

- Hybrid quantum/classical algorithms

- Native quantum algorithms

- Quantum machine learning

- Quantum cryptography

- Quantum communication

- Quantum sensing

- Advanced quantum simulators

- Quantum computing

- Quantum annealing

- Topological quantum computing

My take

Martin Casado, General partner, Andreessen Horowitz

Enterprise business and technology leaders are not that different from venture capitalists. In an era in which innovation is a business imperative, we share many of the same challenges. We’re all trying to predict which technology trends have the potential to drive the most value.

There’s no secret formula for finding the next big breakthrough. Andreessen Horowitz partners sit through thousands of entrepreneur pitches every year and serve as board members for hundreds of startups. Those conversations are a window into the future—not necessarily because they allow us to identify the next new tech trend but because they give us insight into how current industry trends are evolving to influence enterprises in the future. Here are three current trends we expect to leave their mark on enterprises in the coming three to five years.

Ascendancy of data. In the past, a software system’s code dictated its performance, accuracy, security, and compliance. Increasingly, these characteristics are dictated by the data being fed into systems: The code (via machine learning) obediently learns from the data and spits out business insights and predictions. Technologists know how to handle code, but dealing with data is intrinsically more challenging. Data is heavy-tailed and complex, and like a fractal, it’s self-similar—closer to computational physics than to engineering. The toolsets for working with data are completely different than those for working with code. As a result, we expect the entire enterprise technology stack to be refreshed to accommodate data’s primacy over code.

The ascendancy of data also presents a volume challenge. The availability of inexpensive data warehouses allowed enterprises to amass vast amounts of data. But the economies of scale that are often seen with software and hardware products are missing—in fact, the unit economics of increasing data are almost always worse. Many entrepreneurs and business leaders seem to expect that turning an algorithm loose on a large volume of data will magically conjure valuable patterns and insights. But more data also means more noise, more redundancy, and more effort to keep it fresh. Identifying the value of their data can help enterprises develop a sustainable plan for using it to gain competitive advantage and build a defensible long-term business.

Cost and margin structure of cognitive technologies. Businesses are using machine vision, machine learning, and natural language processing to tackle problems at scale that we could never dream of before. Consider, for example, large operational centers that deal with huge amounts of data or industrial applications such as picking and packing agricultural products.

Software-driven business process automation historically helped companies achieve higher profit margins, but we don’t fully understand the margin structure for some cognitive technologies, particularly those that use a lot of data storage and computational power—for example, image processing, text recognition, and natural language processing. It costs roughly the same to use human workers to make complex judgments using unstructured and paper-based information as it does to use cognitive technologies to do the same. We can begin to see a cost differential when we use cognitive technologies to deal with more structured and electronic information.

The progress we’ve made has led some business and technology leaders to adopt an “end of theory” philosophy. In this line of thinking, even when a company doesn’t know a business problem exists, applying artificial intelligence, machine learning, and/or automation will reveal both the problem and its solution. But until it’s clear that leaning heavily on these technologies can actually lower costs, a good way to deliver value is to first understand the costs and margins of cognitive applications and, then, determine the appropriate combination of human workers and cognitive technologies that produces the best cost/performance ratio.

Bottom-up technology adoption. The decentralization of technology buying from procurement specialists to the business end user will continue to have huge implications for product design and adoption. For many years, CIOs and other technology leaders have been managing the security, support, and budget implications of this issue—variously termed consumerization of IT, “consumerprise,” B2C2B, or shadow IT—aiming to strike a comfortable balance between controlling technology and employee productivity and morale. Consider the user-driven enterprise adoption of consumer-branded smart watches, hardware security keys, SaaS productivity and collaboration solutions, and even open-source core infrastructure.

Today’s most promising startups are betting their businesses that bottom-up enterprise technology adoption will soon encompass nearly every enterprise technology product and solution. When everybody’s a technology buyer, products will continue to become easier to use and the cost per product or license will decrease. The shift to bottom-up technology adoption mandates a massive shift in the way organizations adopt and purchase technology. Businesses will need—soon—a comprehensive plan for addressing this purchasing shift.

***

The startups and entrepreneurs we talk to are our eyes and ears in the market. Their product and solution pitches help us understand consumer and business problems and how today’s technology and business trends are evolving to address them. By understanding how bottom-up technology adoption, the ascendancy of data, and the cost and margin structure of cognitive technologies are influencing their business models now and will continue to do so in the future, enterprises can take a step toward future-proofing their businesses to support agility and innovation.

Backcasting: From probable to profitable

By stepping back from the possible, through the probable, we can get to the sober work of backcasting: planning today’s technology decisions and investments in concert with tomorrow’s likely ends. Enterprising leaders see these emerging technology prospects not as threatening disruptions or distracting shiny objects but, rather, as the building blocks of their organization’s future.

There’s growing interest among enterprises in looking beyond what’s new to what’s next, and little wonder—an understanding of what’s coming can inform early budget planning and enable the relationships that make it possible to reap the associated rewards when the time comes.

But at present, many enterprises lack the structures, capabilities, and processes required to harness these macro forces and innovate effectively in the face of exponential change. It might be tempting to fund a stable of smart scientists and engineers and let them pursue ideas and technical proofs of concept in a vacuum. While this approach can bring technologies to life, this group often struggles to create solutions that truly add lasting value to the company.

Leading organizations have a disciplined, measured innovation program that aligns innovation with business strategy and a long-term technology landscape. They take a programmatic approach to sensing, scanning, vetting, experimenting, and incubating these future macro technology forces—until the technology, the market, and the business applications are ready on an enterprisewide scale.

Clarify the landscape of new technologies and players

With sensing, organizations can stay on top of new developments in technology, and identify and understand how they are driving advancement. Establishing a culture of curiosity and learning in your organization helps but likely won’t be enough, considering the pace of change and the complexity of emerging fields. To survey the landscape and unearth the technologies and companies that may be defining the future, leaders should consider several concurrent approaches.

- Sense-making. Many organizations are establishing internal sensing functions to explicitly monitor advances and imagine impacts on the business. Begin building hypotheses based on sensing and research. Identify a macro technology force and hypothesize its impact on your products, your production methods, and your competitive environment in early and mid-stage emergence. Then perform research around that hypothesis, using thresholds or trigger levels to increase or decrease activity and investment over time.

- Trusted collaborators. Companies can leverage their existing set of vendors and alliances to get the pulse of their direct and closest collaborators. Consider holding joint innovation workshops to understand the variables directly affecting an organization. It can help your organization tap into new thinking, and your established partners’ road maps can, in turn, spur new ideas. This can also start the process of collaboration within traditional circles while identifying and launching leading change agents.

- A nontraditional path. Some leading companies are also forging new relationships. Develop a broader ecosystem with nontraditional stakeholders—such as startups, scientists, incubators, venture investors, academia, and research bodies—which can lead to a wide range of fresh perspectives. In turn, your organization can serve as the lifeblood for startups, whose existence may rest on finding the right partners and customers quickly to create an interconnected market.

Harness the possible

At some point, your research reaches a threshold at which you can begin exploring the “state of the possible.” In early stages, forgo exhaustive business cases and instead focus on framing scenarios around impact, feasibility, and risk.

- Show versus tell. Look at how others in your industry are approaching or even exploiting these forces. At this point, show is better than tell. Try to collect 10 or more examples of what others are doing. These can help you and your colleagues better understand the technology forces and their potential.

- State of the practical. Once your organization better understands the future macro forces and their potential impact, convene around the “state of the practical.” Specifically, could those same approaches harm or benefit your business? What about this opportunity is desirable from a customer perspective? And importantly, do you have the critical capabilities and technology assets you will need to capitalize on this opportunity?

- Exploration into experimentation. To move beyond exploration and into experimentation, try to prioritize use cases, develop basic business cases, and then build initial prototypes. If the prototypes yield results—perhaps with some use case pivots—then you may have found a winning combination of technology, innovation, and business strategy.

Incubate new products, solutions, services, and business models

When the experiment’s value proposition meets the expectations set forth in your business case, then you can consider more substantial investment by moving into incubation, where you foster the growth of technology-driven products, solutions, services, and even new business models.

- Dedicated team. Some companies have established innovation centers that are separate from the core business and staffed with dedicated talent. These formal initiatives typically have incubation and scaling expertise. They may also have the capacity to carry out the level of enhancement, testing, and hardening needed before putting your innovation into production.

- Turtle or hare? Be cautious about moving too quickly from incubation to full production. Even with a solid business case and encouraging experiments with containable circumstances and uses, at this stage your new innovation is not proven out at scale. You will likely need an incubator that has full scaling abilities to carry out the level of enhancement, testing, and fixes needed before putting your new idea out into the world at full force.

Bottom line

Some think of technology innovation as nothing more than eureka! moments. While there is an element of that, harnessing advanced technology to create new opportunities is more about programmatic, disciplined effort, carried out over time, than it is about inspiration. Organizations should consider how to establish a program that can effectively identify, evaluate, and incubate these future macro technology forces to transform their enterprises, agencies, and organizations—before they themselves are disrupted. In a world of seemingly infinite unknowns, it is possible to focus attention on a meaningful collection of known technologies that, taken together, can help you chart a path to the next horizon.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

Human experience platforms Article5 years ago

-

Architecture awakens Article5 years ago

-

Horizon next Article5 years ago

-

Executive summary Article5 years ago

-

Introduction Article5 years ago