Architecture awakens Let the evolution begin

21 minute read

15 January 2020

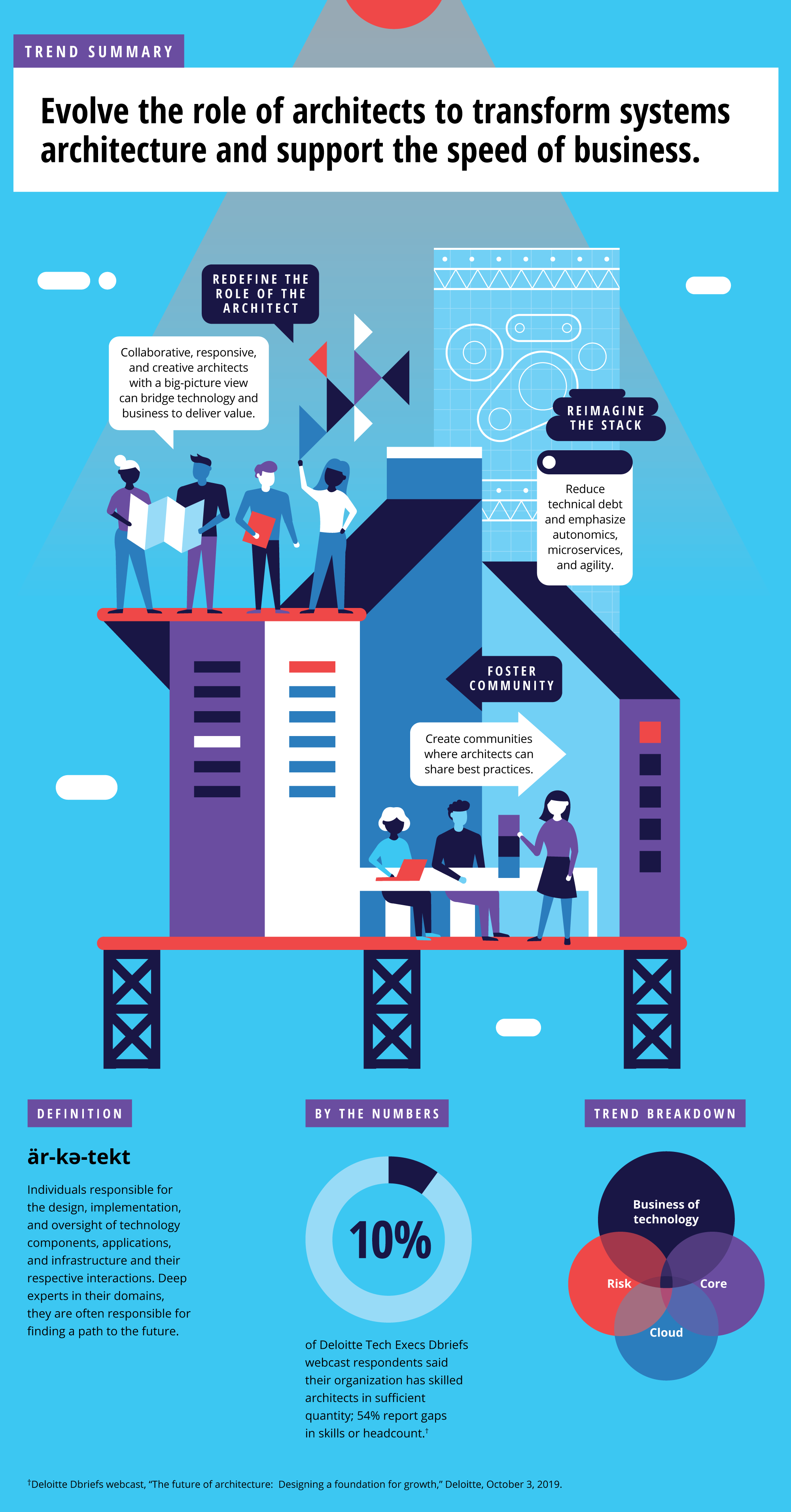

With technology architecture growing in strategic importance, we expect to see more architects playing a large role in system operations—and joining software development teams that are designing complex technology.

The architecture awakens trend is a direct response to external pressures many CIOs face today. Innovation continues its disruptive march across business and technology landscapes. Young companies—largely unburdened by legacy systems and technical debt—are moving quickly to harness digital advances. And some established organizations are struggling to keep pace, with IT systems that increasingly seem slow, rigid, and expensive. Deloitte’s 2018 Global CIO Survey found that only 54 percent of CIO respondents thought their organization’s existing technology stacks are capable of supporting current and future business needs.1

Learn more

View Tech Trends 2020

Download the Executive Summary PDF

Listen to The evolution of systems architecture design podcast

View the infographic

Watch the video

Create a custom PDF

Go straight to smart. Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Growing numbers of technology and C-suite leaders are recognizing that the science of technology architecture is more strategically important than ever. Indeed, to remain competitive in markets being disrupted by technology innovation, established organizations will need to evolve their approaches to architecture—a process that can begin by transforming the role technology architects play in the enterprise.

In the coming months, we expect to see more organizations move architects out of their traditional ivory towers and into the trenches. These talented, if underused, technologists will begin taking more responsibility for particular services and systems—and will become involved in system operations. The goal of this shift is straightforward: to move the most experienced architects where they are needed most—to software development teams that are designing complex technology. Once redeployed and empowered to drive change, architects can help simplify technical stacks and create technical agility that currently gives younger competitors a market advantage. They can also be held directly responsible for achieving business outcomes and resolving architectural challenges.

Moreover, companies embracing the architecture awakens trend will begin redefining the architect role to be more collaborative, creative, and responsive to stakeholder needs. Big-picture architects may find themselves working in the trenches on multidisciplinary project teams with application-focused architects and with colleagues from IT and business. Going forward, their mission will be to do bold new things not only with traditional architectural components but with disruptive forces such as blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning.

The architecture awakens trend is grounded in a business logic that CEOs, CFOs, and brand leaders understand: Investment, careful planning, and nurturing can make a company grow. And investing in architects and architecture and promoting their strategic value enterprisewide can evolve the IT function into a competitive differentiator in the digital economy.2

Architects go big

How do enterprise teams use architects today? Do they use them because they have to, or because architects make their lives easier and projects more impactful? A big metric of success for architects is that enterprise teams want to work with them. Unfortunately, in some IT organizations architects rarely work shoulder to shoulder with their business or even IT peers. To transition from “doing architecture” to delivering value, architects should be given opportunities to work in different ways, develop their skills, and become recognized leaders in their technology discipline.

These opportunities include:

- Driving agility and speed-to-market. As technology complexity and the pace of innovation accelerate, architects can play an instrumental role in helping to understand the bigger picture in terms of operating and managing complex system landscapes such as hybrid, multi-cloud, and edge workloads. Architects can also help define how DevOps and NoOps architectures and practices should be structured and help drive the cultural and training efforts needed to make the initiatives successful.

- Becoming more accountable for solution outcomes. Architects—like everyone else in IT—should be able to thrive within constraints of budget, schedules, and skill shortages. As architects begin working more closely with fast-moving development teams, their remit will expand to include designing for the specific architectural and technology needs of individual projects. For architects unaccustomed to working “in the weeds” with front-line technologists, this represents a sea change in approach. Architects, along with the rest of the team, should be held accountable for overall project outcomes.

- Increasing developer productivity. IT leaders can enhance developer productivity by building architectural concerns into off-the-shelf tools and languages, thus removing any need for developers to make architectural decisions. The work of tailoring developer tools and languages requires hands-on collaboration between architects and developers with architects obliged to stay grounded and current in a rapidly changing technology landscape.

- Balancing business and technology priorities. To the nontechnical business laity, architects can seem more like academics than technologists. Their proposals, while conceptually sophisticated, may be unbounded by real-life constraints of time and budget. As the architecture awakens trend picks up steam, architects will work to become more fluent in the goals and strategies of the business so that they can credibly make tradeoff decisions that balance technology and business priorities. Without this broader understanding of business, the architect’s role—and influence in the broader enterprise—will be limited.

- Optimizing operating costs. As organizations migrate to the cloud, there are a variety of different options with differentiated cost profiles and degrees of vendor lock-in to consider. Choosing infrastructure-as-a-service, platform-as-a-service, software-as-a-service, or function-as-a-service can lead to orders-of-magnitude differences in operational costs, depending on the nature of service/system usage and access patterns. System designers will increasingly need to move from static cost sizing and estimation to more dynamic predictions as part of the system design process.

- Spreading architecture’s message. It’s not uncommon for architects to feel that their companies underinvest in architecture. The unfortunate reality is that architecture will likely remain underfunded if architects cannot effectively make a strong business case for investing in architecture by connecting its value to specific business outcomes. They need to quantify the value of the business agility, product offerings, and innovative services that architecture enables—and spread architecture’s message across the organization.

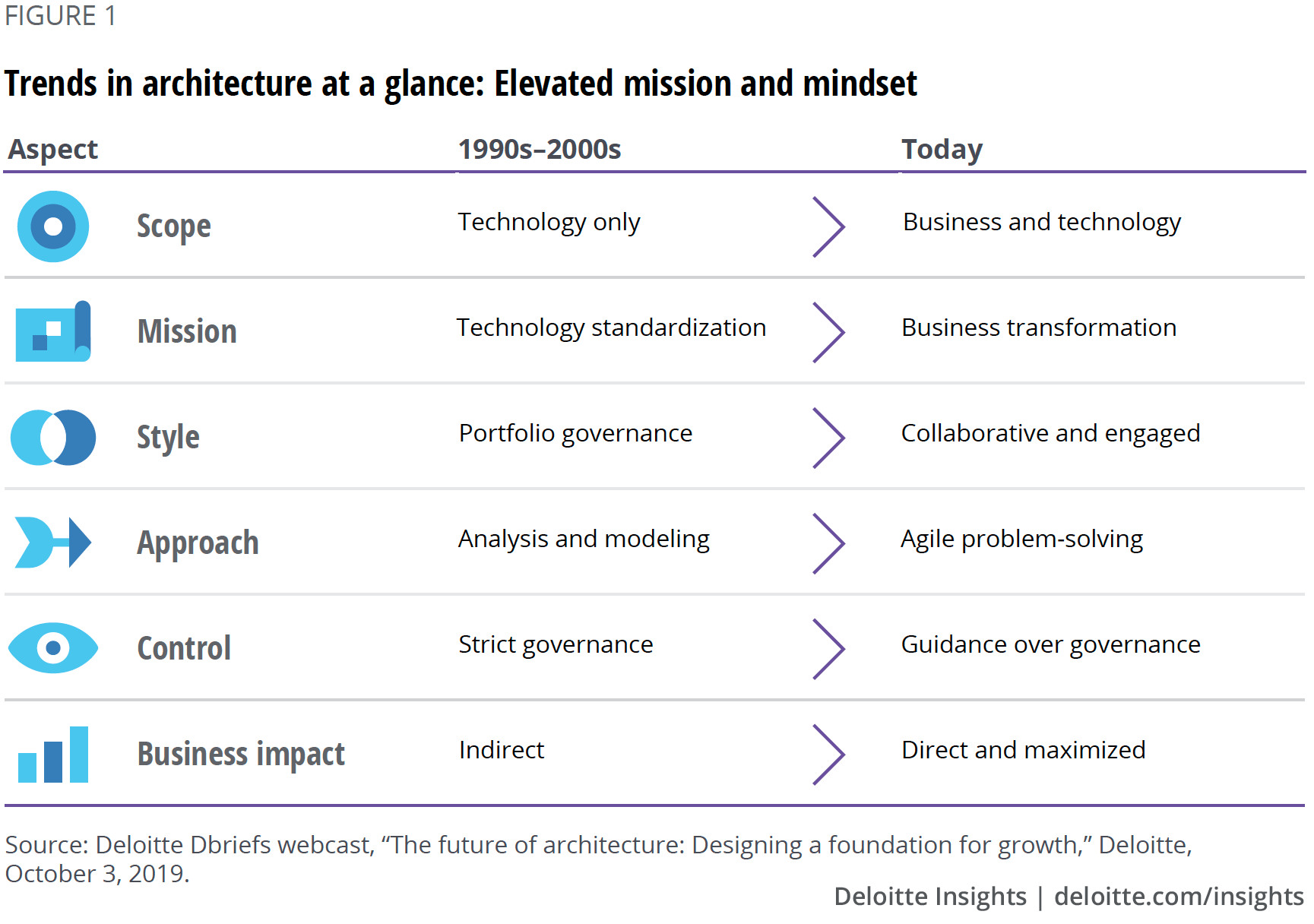

The good news is that many IT leaders are already thinking about ways to grow their architects’ roles. During a recent Deloitte Dbriefs webcast titled “The future of architecture: Designing a foundation for growth,” more than 2,000 CIOs, CTOs, and other technology leaders were asked to describe the future scope of the architect role in their organizations. Forty-two percent said that “architects will be expected to be both more technically specialized, and more attuned to the enterprisewide landscape.”3

Reimagining the technology stack

Incumbents not “born in the cloud” often find themselves hamstrung by decades of legacy technology that suffers from system and organizational inertia. In this environment, IT leaders struggle to deliver new capabilities within timeframes that the business demands.

In response, forward-thinking companies are rebuilding their technology stacks by emphasizing autonomics, instrumentation, and cloud-native tooling. What’s more, they embrace Agile techniques and flexible architectures that can help them compete in a rapidly changing world.4 The urgent need to build and maintain the kind of technical agility that currently gives younger competitors a market advantage is the primary force that will drive the architecture awakens trend over the next 18 to 24 months.

This imperative means that transforming your technology stack is not optional. Future-forward technology stacks should include DevOps and NoOps concepts, and utilize open-source technologies.5 Importantly, the transformed stack can help lower interest payments on technical debt, which will likely go a long way in helping IT create the budgetary headroom needed to deliver new digital products and services.

These kinds of changes won’t come cheap. But to make them more financially manageable, leaders should consider creating explicit budget lines for technology stack items, with business cases. Automated cloud management services, AI workbenches, code quality scanning services, regression test beds, and other architecture investments can potentially increase efficiency and thereby accelerate delivery, lower costs, and more. The goal should be to shift from best practices to deployable patterns, platforms, and tools.

Finally, consider funding exploratory projects that bring together small multidisciplinary teams comprising business experts, architects, and engineers, tasked with recreating existing business solutions using new technologies. Bounded, time-boxed research projects such as these can enhance technology strategies in a number of ways:

- They help IT leaders and stakeholders develop a better understanding of the strengths and limitations of various technologies—think cognitive agents, computer vision, or quantum—and how they could potentially affect architecture designs.

- They help development teams identify optimum technologies for a variety of business use cases—and the specific skill sets needed to eventually execute on these cases. For example, evaluating open-source options requires different kinds of analysis, since open-source developers don’t generally invest in responding to feature checklist requests.

- Exploratory projects can help IT and business leaders get a jump on the competition by uncovering new opportunities to reinvent the business and identify areas that are vulnerable to disruption. With this information, decision-makers can develop strategies for countering disruption (for example, acquisition versus build), for disrupting markets themselves, and for creating the architectural agility needed to pursue these objectives.

It’s not difficult to recognize a causal relationship between investing in technical agility and any number of potential strategic and operational benefits. For example, a flexible, modern architecture provides the foundation needed to support rapid development and deployment of solutions that, in turn, enable innovation and growth. In a competitive landscape being redrawn continuously by technology disruption, time-to-market can be a market differentiator. In this light, consistently funding technology stack modernization initiatives—while remaining mindful of tradeoffs—may be well worth the investment.

Architects reach fighting trim

As the roles of architects and the architecture function itself evolve, it will be important to preserve some aspects of the status quo. For example, even though architects may be working primarily as part of product and service teams, they will still need to connect with one another. CIOs should consider creating online and on-site communities where architects can share in-the-trenches learning, bounce ideas off of each other, and align their approaches to solution shaping and enablement. As an alternative, they could create a matrixed organization in which architects report to product teams and a centralized architecture function. In this model, architects can meet local delivery needs while continuing to share best practices with colleagues. Either way, the important thing is to recognize and sponsor valuable technologists. It’s not just a matter of helping them succeed in the near term. In today’s IT talent market, demand for technology engineers already exceeds the supply, which could put many architectural transformation initiatives at risk.6 Providing experienced architects with opportunities to mentor younger IT talent may soon become a CIO’s most effective means for meeting the staffing demands of tomorrow.

With disruptive change happening at an unprecedented pace, planning architecture deliberately has become critically important. Three decades ago, a small number of technology architects put in place architectures that have enabled their companies to continue processing transactions to this day. Of course, few things in the world of enterprise technology last decades, much less several decades. But the question bears asking: How can we build our systems today to accommodate the innovation and disruption that will surely continue for decades to come? By architecting them effectively. And who can do that? Architects.

Architecture has awakened. Let the evolution begin.

Lessons from the front lines

Enterprise architects get an upgrade

In a market disrupted by the rise of flexible lodging alternatives, hospitality companies are transforming operations to meet guest demand for technology-driven services, conveniences, and experiences. For example, in the last five years, InterContinental Hotels Group (IHG) launched a cloud-based guest reservation and revenue management system, created a common user interface across all hotel-facing applications, and embraced an advanced analytics solution that enables real-time use of structured and unstructured data.

To make the multinational hospitality company a more agile and responsive business partner, IHG’s IT team is modernizing processes and architectures. Cynthia Czabala, IHG’s VP of Enterprise Services, recognized that changes to the deployment and usage of architects could enable rapid adoption of strategic technologies, which would more effectively support the company’s business goals.7 “We needed a systematic process that would align us more closely with business priorities, allow us to rapidly evaluate and deploy technologies, and improve the efficiency of enterprise and solution architects and developers,” she says.

Czabala changed the deployment model for enterprise architecture, shifting the roles, responsibilities, and reporting lines of enterprise architects (EAs). Two-thirds of the EAs, originally part of her centralized team, were moved to serve directly on technical projects, managing business requirements and architectural approaches. Czabala pushed them out to the lines of business to help them better understand plans and priorities. The remaining EAs in the central, smaller team now have a more strategic role. They focus primarily on the first implementation of every technology architectures expected to drive strategic change across the enterprise, such as event-driven architecture, cloud, containerization, microservices, and other future-looking technologies.

In addition, the EAs who remain in Czabala’s centralized team are no longer required to be chargeable resources, freeing them from the constraints of project billing and allowing them to focus on the strategic work of vetting technologies, determining how they should be operationalized and governed, and delivering enterprisewide guidelines and reference models. No ivory towers here, though: EAs work hand in hand with project solution architects and lead developers to deliver and ensure the success of the initial project implementation.

Armed with the EAs’ standardized reference models and road maps, development teams are empowered to design and implement future deployments of these technologies, without duplicating development work or circumventing IT processes. “We trust development teams to follow the guidelines and standards without watching over them,” Czabala says.

All of the architects maintain a sense of community and stay in close contact via weekly architecture forums for sharing information on new concepts and approaches, EA-led working groups charged with building out standards and reference models, and bimonthly town halls that provide specific details about new coding techniques, tools, and technologies.

EAs are far more strategic now that they’ve switched their focus from developer oversight and governance to planning and implementing IHG’s future architecture. And they enable Czabala’s entire team to be more strategic as well. “Being closely aligned with the business and having resources that are looking forward allows us to develop an enterprise architecture roadmap that can evolve at the pace required by the business,” she says. “Working hand in hand with business teams to define and support business strategy helps us be more efficient at prioritizing investments and planning projects.”

Enterprise architects set the direction at Thomson Reuters

In a bid to redefine how it competes and innovates, Thomson Reuters is seeking new ways of designing and building agile, adaptable enterprise architecture. The company’s technology team is rallying resources and investments around digital platforms and defining common, reusable capabilities and services. In addition, the multinational media and information company is transforming its operational and organizational structures, says Jason Perlewitz, director of technology.8

Thomson Reuters’ journey began a couple of years ago, when it began migrating legacy data center systems and applications to the cloud; with an even mix of native cloud-built applications and legacy data-center applications, the company is now at about the halfway point. The company adopted a business-centric approach to technology that emphasized overarching corporate strategy and integrated business partners into the architectural decision-making process.

As part of this holistic approach, Thomson Reuters sought to restructure its technology organizations to optimize the development and use of common processes and reusable capabilities, systematize and speed innovation, and maximize the value of its technology assets across the enterprise. This included a cultural transformation to recalibrate the role of architects to bring both the voice of the customer and a business perspective to architecture development and forge deeper connections between technology operations and system design.

Previously, architects, developers, and operational support were siloed into separate teams that were not closely aligned; the architect’s role was to ensure technology standards and modern practices were incorporated into the technical direction of an entire suite of applications. Thomson Reuters integrated these groups into smaller, agile teams responsible for a single application or specific reusable component, embedding architects in individual teams.

Architects are still technology direction-setters who partner with developers and other technologists, but they’re also responsible for the integration of the application and its operational fitness. Leaders evaluate and incent them not just on traditional technological capability metrics but on operational and business measures that provide an indirect measure of how well technology is serving the business needs and help give architects a deeper understanding of the business mission.

Relevant business metrics include an application’s contribution to positive net promoter scores, customer recommendations, and customer retention and acquisition rates. Operational proficiency might depend on: the inclusion of built-in security, operational support, and system management; the ability to self-diagnose and provide heuristic automation and analysis; testability; and the number of service disruptions.

Technology leaders developed monthly forums to encourage information-sharing and collaboration and foster a sense of community. To support the culture, architects are evaluated via metrics that emphasize sharing and collaboration, such as leveraging reusable capabilities built by others and applying common processes to common problems. And a monthly forum serves as a readout from business functions, which share information and answer questions from technologists about strategy, customer needs, and other key topics.

Other initiatives aimed at increasing architects’ exposure to business and customer needs are percolating. For example, the technology and user experience teams are working on ways to integrate architects into customer meetings to discuss functions and features. Perlewitz is partnering with customer-facing business functions to position architects as the connective tissue between these functions and development teams.

Architects have become invaluable advocates of the platform-centric architecture evolution and technology organization restructuring. “They believe in our vision of making architecture more accessible to the masses and help promote it throughout the company,” Perlewitz says. “Their vocal support and engagement have made a significant impact in driving acceptance to change.”

Engineering an agile enterprise: National Australia Bank expands the role of the technology architect

National Australia Bank (NAB) is in the midst of a multiyear, multibillion journey to transform itself into a financial institution that can respond more quickly and efficiently to customer needs. To that end, the bank is replacing its legacy architecture with a flexible technology ecosystem. Just as important, the organization is reorganizing and training talent to support the digital transformation. Sergei Komarov,9 who has deep experience in enterprise architectural transformation, was hired as one of NAB’s technology leaders.

In early 2019, NAB restructured its enterprise architecture function to support more agile ways of working. Komarov sees technology architecture as a distillation of engineering experience at its core. Good technology architects should be hands-on—building and experimenting with different technologies and architecture models. They should take a holistic view and be accountable for making sure that the architectures they oversee are cohesive and that the parts fit together within the agile ecosystem.

To support this philosophy, NAB’s reorganization introduced a stewardship model organized by services that represent durable assets, or capabilities, of the bank. Three types of stewardship roles were created: service architects, specialized technology architects, and business-facing initiative architects. These complementary roles are vital to the overall architectural function, increasing agility across the bank. For many of NAB’s existing architects, the transition was a dramatic shift from a relatively isolated role to one that’s ongoing, collaborative, and future-focused.

First, each service architect is responsible for overseeing the modernization of a specific business domain service; they are expected to develop a deep understanding of their assigned service, its current and target states, and its proper role in the overall IT ecosystem. And their mandate involves addressing key questions: Is the service resilient and secure? Which applications or systems are destined for obsolescence? Which are up-and-coming? Where are redundancies? How can the service be simplified and improved over time? Is the service loosely coupled with other enterprise services?

Next, specialized technology architects provide in-depth knowledge of technologies that affect multiple services, such as distributed systems, data technologies, and microservices. Technology architects are concerned with specific technology patterns, practices, and tools applicable across many services; they set the technology standards that influence the work of the other two types of architects.

And finally, initiative architects are responsible for the design of a project or business-facing initiative. They work with business units to help them define and shape their technology needs to fit within the goals of the overall agile enterprise, utilizing capabilities delivered through enterprise services.

Agile organizations are built on collaboration—a significant change for architects accustomed to a more separate remit. NAB is using metrics to encourage teamwork and engagement, supported by social and training opportunities. Each architect has a billability target to help them balance their time between project deliverable–oriented work and more proactive strategic planning and thinking. This also helps foster a more effective division of labor that yields a combination of business acumen, expertise in emerging technologies, and in-depth understanding of NAB’s evolving technology estate to achieve common goals.

“The industry has sometimes been confused about the role of the architect in the context of agile, thinking that an agile organization doesn’t require any forethought, planning, or coordination,” Komarov says. “That’s magical thinking. Enterprises are beginning to realize that agility requires a cohesive, flexible IT ecosystem. And it’s the architect’s job to be an expert in the construction of such ecosystems.”

My take

Charlie Bell, Senior vice president, Amazon Web Services

With technology serving as the backbone for differentiated digital experiences, innovative products and services, and optimized business operations, enterprise architecture carries increasingly critical workloads. When it’s agile and scalable, enterprise architecture can drive value and help businesses realize their strategic vision. When it’s not, it can hamstring digital transformation, expand technical debt, and increase system and software entropy—ultimately leading to organizational inertia.

There’s never been a greater need for the steady hand of effective technical leaders who can build and manage flexible, architecturally sound systems aligned with business needs. When our customers meet with us, I expect them to ask questions about our road map or products, but most of them want to understand how our architects lead the design and building of enterprise systems in support of our business strategy.

However, we don’t have the traditional architect role at AWS. The responsibility for technical architecture design lies in the hands of our principal engineers, while our solutions architects help customers design solutions using AWS services. These roles are not functionalized, as is often the case with architects—we discovered that the best mechanism for enforcing common design and centralized thinking is organizing around products. In the early days, we needed a middle-tier application server, but we couldn’t find a cost-effective commercial product that was built for web-based workloads. Several teams were working on duplicative efforts to solve this problem; we took the best one, formed a team around it, and turned it into a product that others could consume.

Today we still use this same model to solve architectural problems. We don’t need to centralize principal engineers. Instead, principal engineers are assigned to product teams—such as Amazon Alexa, Amazon EC2, Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3), or Amazon DynamoDB. We’ve found that being focused on a specific set of customer needs for longer periods of time allows engineers to be more effective than moving between multiple short-term projects.

Our product development approach emphasizes starting with the customer and working backwards to the product. Before any idea is funded, the product team presents to AWS leadership a one-page internal press release that describes not only the finished product but the customer problem it solves, the specific customer impacted by the problem, and its advantages over existing solutions. The team also develops and presents a five-page Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) that includes so-called rude questions, such as, With what aspect of the product will customers be most disappointed?

The review process forces product teams—given a single hour to make their case to senior AWS leaders—to gain a deep understanding of the market, customer needs, and product benefits. I participate in reviews of almost all “working backwards” documents, as does our CEO. We discuss and debate the product’s merits, and if the review team decides to allocate resources, the team moves to the planning phase. Often, the review process reveals product weaknesses, and teams go back to the drawing board, make changes, and prepare the press release and FAQ for a second review. Being a part of this process helps orient principal engineers and product managers around a common goal and allows them to experience the pressures of delivery and customer needs.

As strategic members of our product teams, principal engineers help find solutions to Amazon’s most demanding problems. The chief arbiters of design are charged with delivering artifacts—from designs to algorithms to implementations. They establish technical standards, drive the overall technical architecture and engineering practices, and work on all aspects of software development.

Our principal engineers are visionary, but they’re also pragmatic. To earn the respect needed to be effective technical leaders, they need to be close to the project details. They don’t waste time developing abstract business requirement documents or hand off development guidelines and technology frameworks to project teams—they roll up their sleeves and pitch in. Principal engineers own all aspects of the services they build, from development efforts to operational responsibilities. They spend time with customers and understand and apply themselves to customer problems, but they’re also in tune with their product’s day-to-day operations, helping shape activities such as operational readiness reviews and change management. If something goes wrong with a service in the middle of the night, the principal engineer gets the call.

A self-organized community of principal engineers meets weekly to develop standards, share information, and build relationships. The group holds talks featuring topics such as the design of a specific service or the availability of new ideas or tools. Typically, hundreds of engineers are in the room, with additional thousands watching the video stream. Group members created a set of fundamental values that outline the overarching philosophy of the role and function; these tenets help set performance standards and serve as decision-making guidelines. The community also organizes design and operational reviews that give members opportunities to provide feedback on new services and solutions in development. Several times a year, members hold offsite meetings to build a sense of community and maintain alignment of the different product teams.

Principal engineers have worked in this way since I started working at Amazon more than two decades ago. Because it works so well for us, it’s almost unthinkable that we’d change. As their teams’ guiding technical light, principal engineers set the standard for engineering excellence, provide unprecedented understanding of customer problems, and equip our enterprise architecture to maximize our innovation speed.

Executive perspectives

Technical debt and legacy technology constraints can undermine even the best innovation strategy. If your organization is so hamstrung by system complexity that it is unable to take advantage of new tools that are disrupting your markets, your company is likely already losing its competitive advantage. CEOs typically do not engage directly with architects, but they can support architects in their expanded roles by creating an enterprisewide culture of risk-taking, innovation, and cross-pollination. This means encouraging everyone to step outside of their skill silos and broaden their perspectives by talking to others across the organization. Because architecture is now more strategically important than ever, it follows that architects should engage regularly with strategy stakeholders of all stripes. Diverse perspectives often lead to more effective decision-making—a rule of leadership that CEOs have long embraced. This same rule can benefit architects. They are, after all, the individuals who understand existing systems and constraints and are best positioned to design the strategies that will support emerging technologies and strategic priorities during the next decade.

As demands for computing and data services grow, CFOs, CIOs, and architects can collaborate to future-proof technology and reduce organizational technical debt. They should consider four key questions about their existing computing architecture. First, can the existing computing architecture meet the company’s growth needs, either organically or through M&A? Second, is it flexible enough to support strategy changes, for example, divesting a business without leaving stranded costs? Third, what are the primary risks to the architecture—for example, obsolescence, scaling, and technical debt? Finally, how will architecture shape future capital expenditure and operating expense models? For example, with the growth of cloud services, moving key architecture components to the public cloud may drive operating costs and capital expenditures to differ significantly from those in models. Working together, finance and IT can model out likely future tech costs and then allocate capital to flexible architectures that meet the changing needs of the business.

Risk lies in changes being made to existing technology stacks and systems. The more dynamic those changes are, the more important it will be to consider potential risk impacts from the earliest planning stages of any project. As you begin redeploying architects to IT’s front lines, consider embedding them in DevSecOps teams to make sure that architecture concerns are factored into any projects. Likewise, in architecture transformation initiatives, architects can take greater responsibility for understanding and addressing risk issues. Unfortunately, in some initiatives, planners treat risk as a box to check. Without a baseline understanding of a project’s risk profile, it becomes more difficult to determine the most effective way of managing risk in the future. Does the project require just only an initial assessment, or is it sufficiently dynamic to justify ongoing assessments? And what impact could flexible, component-based architectures have on overall risk profiles? The stakes are too high to answer these questions retroactively. Modernization and risk planning should be part of the same process.

Are you ready?

- What role do your most senior architects play in shaping future systems and services? How are they directly responsible for achieving business outcomes?

- What teams are your architects part of? With whom do your architects work daily—each other, software developers, business colleagues, end users?

- What programs do you have in place to recruit, grow, and retain skilled architects with both depth and breadth across technology architecture domains?

Bottom line

IT leaders at incumbents are realizing that the science of architecture—and the technologists who practice it—are more strategically important than ever. The architecture awakens trend offers CIOs an opportunity to move architects from their traditional ivory towers to the IT trenches where their talents can have greater impact. Empowered architects can then work at the vanguard of digital transformation efforts, turning rigid architectures into flexible platforms for future business success.

Learn more

- The future of work in technology: Get a glimpse of what awaits the technology workforce of tomorrow.

- Deloitte on Cloud Blog: Stay on top of the latest cloud news, views, and real-world insights.

- How open source software is turbocharging digital transformation: Explore the ways OSS is sparking collaboration and productivity.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

Human experience platforms Article5 years ago

-

Architecture awakens Article5 years ago

-

Horizon next Article5 years ago

-

Executive summary Article5 years ago

-

Introduction Article5 years ago