Human inside: How capabilities can unleash business performance Companies need human capabilities more than ever. What can organizations do about it?

57 minute read

26 June 2020

As business pressures only increase, organizations need to help develop workers’ human capabilities—curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and courage—and encourage their application across all levels and departments.

Introduction

In the future of work, a paradox is becoming increasingly apparent and important: The more advanced and pervasive technology becomes, the more important humans are to the equation—humans as customers, humans as buyers, humans as engines of growth and innovation, humans as users, collaborators, and stakeholders. And leaders are seeing fresh importance in the ways in which organizations deploy and develop their people to create new value and navigate increasing ambiguity.

Learn More

Explore the future of work collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

As unexpected events proliferate and the pace of change quickens, companies are under more pressure than ever: performance pressure to deliver not just consistent financial returns to investors but noteworthy and increasing returns, pressure from customers for products and services that don’t just meet needs but deliver more and different value, and pressure from talent, for material well-being and aligned values and support for opportunities and individual development. In the short term, the immediacy of any one of these pressures can seem irreconcilable with the others.

And this only becomes more pronounced when large unexpected events further accelerate the pace of change. For a company looking to grow and thrive in a fast-paced and ambiguous future, meeting these needs for increasing returns and new types of value and meaning will require differentiation and deep relationships. Human capabilities—curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and courage—applied by workers across all levels and departments will be key for the type of differentiation, relationships, and new value creation needed to navigate these pressures and sustain success.

Collectively, these enduring human capabilities are like superpowers. They course beneath the surface or lay dormant in every member of the workforce with the potential to deliver real benefits. They help navigate ambiguity and deliver greater impact. Organizations can draw on these powers to accomplish far more—to jump higher, run faster, see farther, maybe even challenge the laws of the universe.

An untapped opportunity

But employees’ powers are largely dormant or undiscovered: In our research, we have found few companies focusing on developing capabilities across the organization.1 A few focus explicitly on a single capability; most often, companies target only leaders and high-potentials for development. Many workers don’t feel they have permission or opportunity to use their capabilities often in their daily work.

Why aren’t companies more focused on developing and making use of the human capabilities in their organizations? Why is this still an unrealized opportunity?

More than anything, based on our conversations with executives, the answer appears to revolve around two questions for leaders: 1) Can capabilities—curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and courage—drive significant corporate performance? 2) Given that these capabilities seem nebulous, what can a leader do to build them within an organization?

Why aren’t companies more focused on developing and making use of the human capabilities in their organizations? Why is this still an unrealized opportunity?

The business benefits

What can organizations gain from cultivating these capabilities across the workforce? Tangible benefits:

- In an environment where customers demand new and more targeted types of value, the ability to create more and more value. Capabilities can enable new value creation by helping workers identify unseen problems and opportunities and develop approaches to address problems and opportunities more effectively and with greater impact.

- In an environment where specific skills become obsolete faster, a workforce able to continuously adapt and acquire needed skills.2

- In an environment where companies struggle to access the talent they need, the ability to better access talent and increase motivation by making the day-to-day work experience more satisfying and meaningful.

Cultivating capabilities is a win-win, delivering value for the company, the customer, and the workforce.

These capabilities are increasingly relevant in today’s business environment.3 Rapidly changing conditions, new and unforeseen needs, the breakdown of standardized processes and the status quo—none of it feels academic or futuristic. This is immediate, and the past several months have seen any number of examples of workers responding to and redefining around that immediacy.

Consider: Floor staffers at retail fabric-hobby stores, recognizing dual needs—for PPE and meaning—quickly developed a “mask-making bundle” for customers who would find purpose making masks to support local essential workers. When automakers were asked to produce ventilators, manufacturing engineers and workers on factory floors found novel ways to repurpose equipment. Around the world, medical workers and others tinkered with ways to make ventilators serve more patients or fashion new ones from unexpected supplies. Frontline employees have hustled to anticipate rapidly changing needs while adapting to changing conditions.

Imagine if these weren’t one-off examples born of crisis. Imagine what you could accomplish if everyone in your workforce was applying all of their human capabilities as these groups have done, not to a pandemic but to daily problems and opportunities, large and small.

How to approach cultivating capabilities

The good news: Not only are human capabilities more necessary than ever—there are initiatives leaders can undertake, now, to begin drawing out and strengthening capabilities in their organizations.

And capabilities can only help in an environment that may never return to “normal.” Unforeseen, and unforeseeable, problems and complications, as well as opportunities, will continue to pop up. They won’t all be large or pervasive but may prove no less significant to the organization. Pixar president Ed Catmull describes the imperative thus: “We must meet unexpected problems with unexpected responses.”4 His solution for embracing that reality: more people solving more problems, without permission, all the time. Doing so provides a perfect training ground for cultivating capabilities. In the right environment, problems can intrigue and motivate—piquing our curiosity, capturing our imagination, demanding creativity, and creating urgency and commitment.

For companies, human capabilities aren’t nebulous—they can achieve real business impact. To get there, leaders need to encourage greater application of human capabilities to the work of the organization, especially for frontline workers.

How can organizations move to cultivating employees’ capabilities?

Redesign the work environment. Many environments today can be indifferent or hostile to human capabilities.

Redesign business practices. Focus on the broader practices for learning in a workgroup.

Focus on the capabilities. Capabilities can be exercised in the flow of work through a set of behaviors. These behaviors can be coached.

Support frontline managers. The frontline manager or supervisor is central to both coaching behaviors and creating an environment where workers can apply capabilities.

Daunting? Maybe, but organizations don’t have to wait to get started. These efforts can be tackled in parallel and not as a big-bang rollout to the whole company at once, either. Cultivating capabilities isn’t a one-and-done effort—it’s ongoing, part of how work gets done. Individuals and the organization can get better at it with practice and support.

What do we mean by “human capabilities”?

Human capability: Attributes that are demonstrated independent of context. Capabilities have value and applicability across different outcomes, sectors, and domains; they do not become obsolete.

Skill: The tactical knowledge or expertise needed to achieve work outcomes within a specific context. Skills are specific to a particular function, tool, or outcome, and they are applied by an individual to accomplish a given task.

The distinction between capabilities and skills is deliberate; the way we use and develop them and the ways they are applied, practiced, and assessed is fundamentally different.

Working definitions:

Curiosity: Seeking to learn through questions and exploration

Imagination: Seeing potential that hasn’t been seen before

Creativity: Innovating new approaches; using resources in unexpected ways

Empathy: Understanding and considering others’ feelings, experiences, needs, and aspirations

Courage: Acting despite uncertainty or opposition

These enduring human capabilities are:

- Innate—everyone has these capabilities, in that they are observable in young children, without special training. Like muscles, capabilities can be underdeveloped and atrophy from lack of use.

- Improvable—capabilities aren’t conducive to training. People will start at different levels of strength or atrophy, but as with muscles, capabilities can be strengthened and developed through exercise.

- Interconnected—capabilities work together, building on and balancing each other; they should be cultivated together.

Why do capabilities matter?

Organizations face constant trade-offs on where to invest time, energy, and capital. The stakes around these trade-offs only become more heightened as companies face increasing pressures both immediate and longer-term. The pace of change is accelerating and in ways that are viscerally felt in every part of our lives, around the globe. Not just technology. Advances in core digital technologies have been accelerating for many years, but those advances have now spawned acceleration across every other field, from health care to farming to getting from point A to B, and changed our expectations as consumers and workers along the way. The implications of much of this change are unclear and possibly unknowable but it is both rich with opportunities and out of sync with the status quo.

In this environment of increasing ambiguity, rapid change, and demand for increasingly specific and personalized value, companies must find new ways to use their people and technology to create and deliver value. The most human of capabilities may hold the keys for unlocking new value.

Cultivating human capabilities offers tangible business benefits

Curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and courage.5 That’s hardly a comprehensive list of the important contributions that humans bring to work, but we chose these five because anyone in the workforce has the potential to access, use, and strengthen these enduring capabilities under the right conditions;6 because we believe they have not just the most potential impact but are actually most critical to creating and sustaining value in the business environment of tomorrow and beyond; and because many organizations today largely overlook them.

Human capabilities such as imagination and curiosity can feel nebulous, difficult to quantify, even “fluffy.” But once applied to the work of the organization, capabilities offer a wide range of benefits. The organizations that choose to focus on and invest in cultivating capabilities can realize fruitful, long-lasting benefits that will position them to unlock new value and achieve accelerating results.

Capabilities help organizations: see previously unseen problems and opportunities, evolve new approaches to increase impact, support workers to continuously adapt and acquire skills, expand horizons, and create a win-win environment where workers can better grow and develop.

See previously unseen problems and opportunities. These new problems and opportunities are uncovered because capabilities help workers read and understand context in much richer and real-time ways. Context can be thought of as the environment and relationships around someone or something—now, in the past, and in the future. It helps workers see and understand the needs, aspirations, and constraints/conditions of customers, internal participants, and other stakeholders.7 Capabilities are critical to delivering value because in today’s diverse world, organizations can no longer do the same thing for everyone; they must consider the context of the various groups they serve. For example, when a group of autoworkers donned a 30-pound “empathy belly,” they developed insight into the needs of other stakeholders, including pregnant women, when designing and configuring vehicles. Empathy and curiosity helped uncover pain points and opportunities to create improved, differentiated customer experiences.8 Workers began to question how other stakeholders’ unique needs and desires might affect their interaction with the company’s products and services.

Capabilities’ benefits are hardly limited to improving workers’ ability to uncover problems and opportunities specific to customer needs—they also support workers’ understanding of what might create value for colleagues. Workers can use capabilities to anticipate and respond to peers’ needs and aspirations. Consider: A member of an analytics team at a retail organization may notice peers on the finance and accounting teams opening multiple dashboards from various data visualization tools to support their work; empathy helps the associate see the burden the process puts on others; curiosity and imagination help her see an opportunity to provide integrated, meaningful data to colleagues; excitement about the potential value fuels her courage to reach out to peers to form a workgroup tackling this issue. When workers use capabilities to anticipate colleagues’ needs, they will uncover problems and opportunities that will lead to continuously reinventing and improving the way their organizations work.

Evolve new approaches to increase impact. Using capabilities to discover unseen problems and opportunities is a first step, but capabilities can also deliver new value by helping workers develop approaches to those problems and opportunities. For example, a recent Harvard Business Review article highlights how supermarket data could be used to generate not only coupons but tailored recipe suggestions based on customer purchase data. Capabilities might uncover a common but “unseen by the company” problem of unused groceries and further help generate a creative, imaginative solution that provides new value to customers—reduced waste and novel meal ideas.9 When workers from all levels, departments, and roles actively search for and identify new problems and opportunities, they can surely produce new approaches that result in a plethora of projects, solutions, and products to explore and develop. These unseen problems and opportunities will bring the opportunity to deliver new, untapped value for the organization.

The entrepreneurship that many companies desire in hiring10—mobilizing resources to move from insight to valuable approach—arises from an individual’s capabilities coming together in the right motivating and supportive environment. Capabilities can help workers better respond to unexpected situations when addressing these unseen problems and opportunities. Over the last few decades, customer demand has evolved to focus more on personalization in the form of specialized products and individualized services. In parallel to this shift, technologies and services that automate and manage routine tasks have grown significantly, leaving workers to focus more on nonroutine tasks and exception handling. Despite the greater need for exception handling, many organizations still rely on strictly defined processes and procedures. Workers who use their capabilities to address each unique situation will be exposed to more insights and potentially useful approaches. When faced with a nonstandard problem, workers can tap into their capabilities to effectively respond by developing unique approaches that deliver increased impact for the organization.

Support workers to continuously adapt and acquire skills. Workers are no longer guaranteed that the skills with which they enter the workforce will be relevant over the next few years, let alone throughout their entire career. Because of skills’ shrinking half-life, many organizations are scrambling to rapidly upskill and train their workforce just for today’s work. As described in the 2019 Human Capital Trends report Learning in the flow of life, while 77% of respondents reported leaning toward “training rather than hiring” for the skills needed, many are beginning to understand that L&D groups can’t keep up with demand through training programs and tools.11

In an economy that desperately needs more and more new skills, refreshed more and more often, organizations that cultivate capabilities will benefit from workers who are more eager and motivated to acquire new skills through a variety of channels in the flow of work and life. When faced with a challenge or obstacle, curious workers may seek to learn a new tool, research a specific topic, or opt into additional training.12 Consider the example of a pizza chef who got curious about technology when he was tasked with calibrating a new set of kitchen-automation tools. His passion for pizza kept him tinkering with the machines, and he quickly realized that to progress, he needed to know more about AI and machine learning. He sought out everything he could, including talking to technologists in other industries, taking online learning, connecting with a hacker community, and working with a restaurant equipment vendor to develop mobile ovens.

Using capabilities to continuously upskill also helps workers be more adept at navigating the challenges and uncertainty of the future. In the Human Capital Trends survey, 81% of respondents saw the “ability to lead through more complexity and ambiguity” as a requirement of 21st-century leaders, but the front line feels it, too.13 Capabilities help workers gain more than new skills—similar to muscles, when capabilities are used regularly they strengthen each other and create a reinforcing cycle of skill adaption and deepened capabilities.

Expand horizons. The core value of this set of innate capabilities is to expand horizons and “open the aperture,” enabling the company to see more than most organizations see by helping look more broadly across the boundaries of functional silos and industry or market definitions, more deeply than the transaction, and across time to what might emerge. The capabilities amplify other initiatives and enable additional capabilities such as critical thinking, analytic thinking, sense-making, emotional intelligence, teaming, and social intelligence (figure 1) that help organizations focus efforts and act together more effectively as technology and social expectations profoundly change the work, workplace, and workforce.

Without the innate capabilities to help the organization look up and around, however, other developed capabilities will tend to deliver marginal, incremental impact. This problem will only worsen as technological acceleration and deeply interconnected global systems lead to more rapidly changing conditions, sudden and significant disruptions, and increasing pressures. As problems and opportunities continue to surface at an increasing rate, innate capabilities will be critical to knowing where to apply focus and effort to create value.

Improve workers’ growth, development, and meaning. While capabilities can help drive business performance, they are also beneficial for individual employees, providing new avenues for workers to develop more rapidly and reinvent themselves. When workers are encouraged to find new approaches or see context differently, their day-to-day work becomes more engaging and provides constant learning opportunities. Using capabilities helps workers move away from routine, standard tasks to developing, implementing, and learning from new approaches. In a world where many workers perceive AI applications as a growing threat, using capabilities can help them reinvent and provide new value to the organization—and make work more personally satisfying and meaningful. Organizations that use capabilities to support worker development have a strong value proposition to both incoming and existing talent by providing them with career paths that offer constant reinvention and opportunity.

Myths and misconceptions

Long-held misconceptions can get in the way of realizing these benefits. Two of the most pernicious are that the workforce lacks these capabilities and that the organization finds them useful only at certain levels. When confronted with the need for capabilities, some leaders respond, “That sounds great, but most of my people can’t do that” or, “People don’t want to put in that effort” or, “Where would we even start?” Organizations that do focus on capabilities often limit that training to leaders, high-potential individuals, or specific departments or teams. Such limits reinforce the belief that capabilities are applicable for only a small subset and that they are peripheral rather than essential. Limits can also undermine the individual motivation for everyone else to begin using underused capabilities; a constrained program becomes self-fulfilling. When organizations provide additional training, development, and mentoring opportunities to only leaders and high-potential individuals, they send a message to the rest of the workforce that they aren’t worth investing in.

Believing that most of the workforce lacks these capabilities is not only demotivating—it contradicts research suggesting that most people have curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and courage, attributes that can be strengthened and developed through exercise or allowed to atrophy through disuse. Exercising capabilities takes effort—it can feel uncomfortable and risky to expose our imperfect grasp. Yet our recent Worker Passion Survey revealed that most workers are eager to use their capabilities, with 84% reporting that they already possess the innate capabilities. Despite their readiness, more than half of respondents perceive that they are prevented from using their capabilities due to their organization’s focus on speed and efficiency and reliance on set processes and procedures.14

Similarly, when organizations focus only on areas such as product development, research, and marketing, they miss out on the accelerated new value other parts of the organization can produce when using capabilities. Companies can benefit from building capability muscles across the workforce. We focus specifically on how to cultivate them in the frontline because that is likely where most organizations have ignored and discouraged them—and where they are most in need, now, to increase performance.

Exercising capabilities takes effort—it can feel uncomfortable and risky to expose our imperfect grasp.

The innate capabilities really are essential: The muscle analogy is apt, but in some ways, capabilities are more like amino acids that interact in chemical reactions to create energy, power the muscles, and move the body to perform. You can’t cherry-pick only one and say that in aerospace we only need to focus on creativity, but in retail we need to focus on empathy, and imagination will be the capability for the movie and gaming industry. To be effective in the work environment, we must integrate the enduring human capabilities with other abilities as well as with opposing capabilities—for example, blending imagination with critical thinking, curiosity with analysis, and reflection with action. Using capabilities, every worker can get better at reading and responding to context, noticing what’s changed and what’s stayed the same, and recognizing when a tool or approach is no longer appropriate.

Each of the five capabilities offers specific benefits that enable seeing and addressing unseen opportunities to create value.

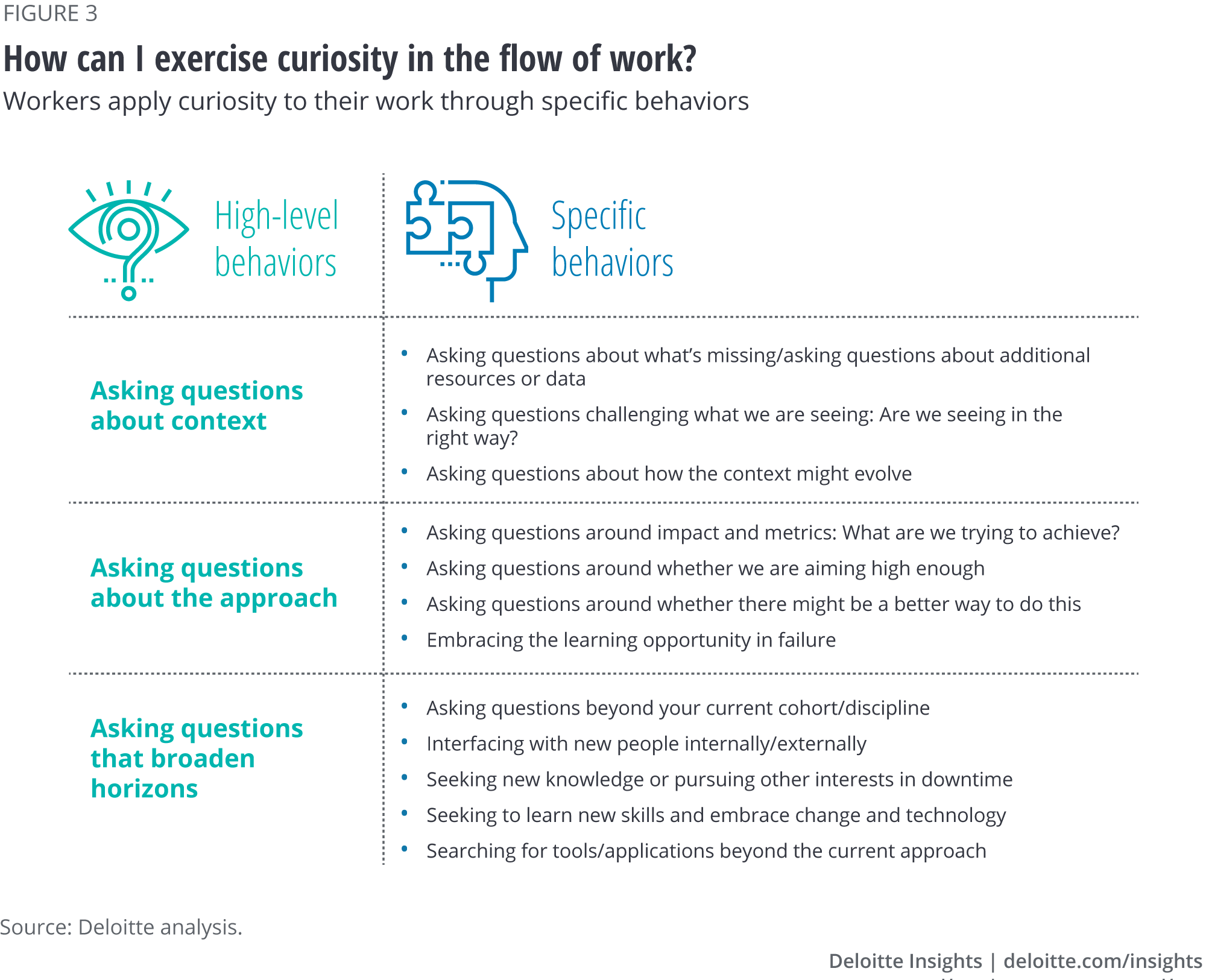

- Curiosity is the inherent realization that there are additional information, resources, and perspectives beyond what is currently visible and seeking to discover them. This often takes the form of questioning. Curiosity benefits work in three ways: Asking questions about context helps surface hidden problems and opportunities; asking questions about the approach helps surface new ways to address problems or opportunities; and asking questions that broaden horizons helps expose adjacencies and blind spots from which opportunities (or disruptions) might emerge. In a recent survey, 84% of workers believed that a curious colleague is most likely to bring an idea to life at work.15

- Imagination supersedes what is “known” to expand our outlook. It is about seeing what doesn’t yet exist, either because it hasn’t been recognized or because it hasn’t emerged or couldn’t be created.16 It is possibly the most critical for relevance and survival in an environment where boundaries and definitions blur and disruption can come from anywhere, anytime. Imagination benefits work in three ways: Looking for existing problems and tools helps to surface opportunities that haven’t been seen; looking for problems and opportunities that might emerge helps keep the organization focused on the implications of rapid change; and identifying new forms of value or impact helps orient the organization toward continuous creation of new value.

- Creativity aims at a solution, finding novel combinations of tools and resources to address a defined question, problem, or opportunity. In the 20th century’s predictable world of mass markets and scalable efficiency, many saw unnecessary risk in diverging from the status quo, and many organizations still carry that aversion. However, the pace of change has led to more frequent and more novel exceptions to the standard processes, while consumers’ demand for more personalized solutions has made standard products and services insufficient. Some organizations have captured significant value by developing new ways to address needs and problems. Job postings data reflects the increased attention with one prominent analysis dubbing creativity “the top soft skill companies need most” in 2019 and 2020.17 It is important to highlight that while many companies incorporate creativity in their leadership trainings, the real value will emerge when the creative behaviors are dispersed throughout the whole organization. Creativity benefits work in three ways: identifying new approaches, framing or designing new approaches, or evolving approaches for greater impact.

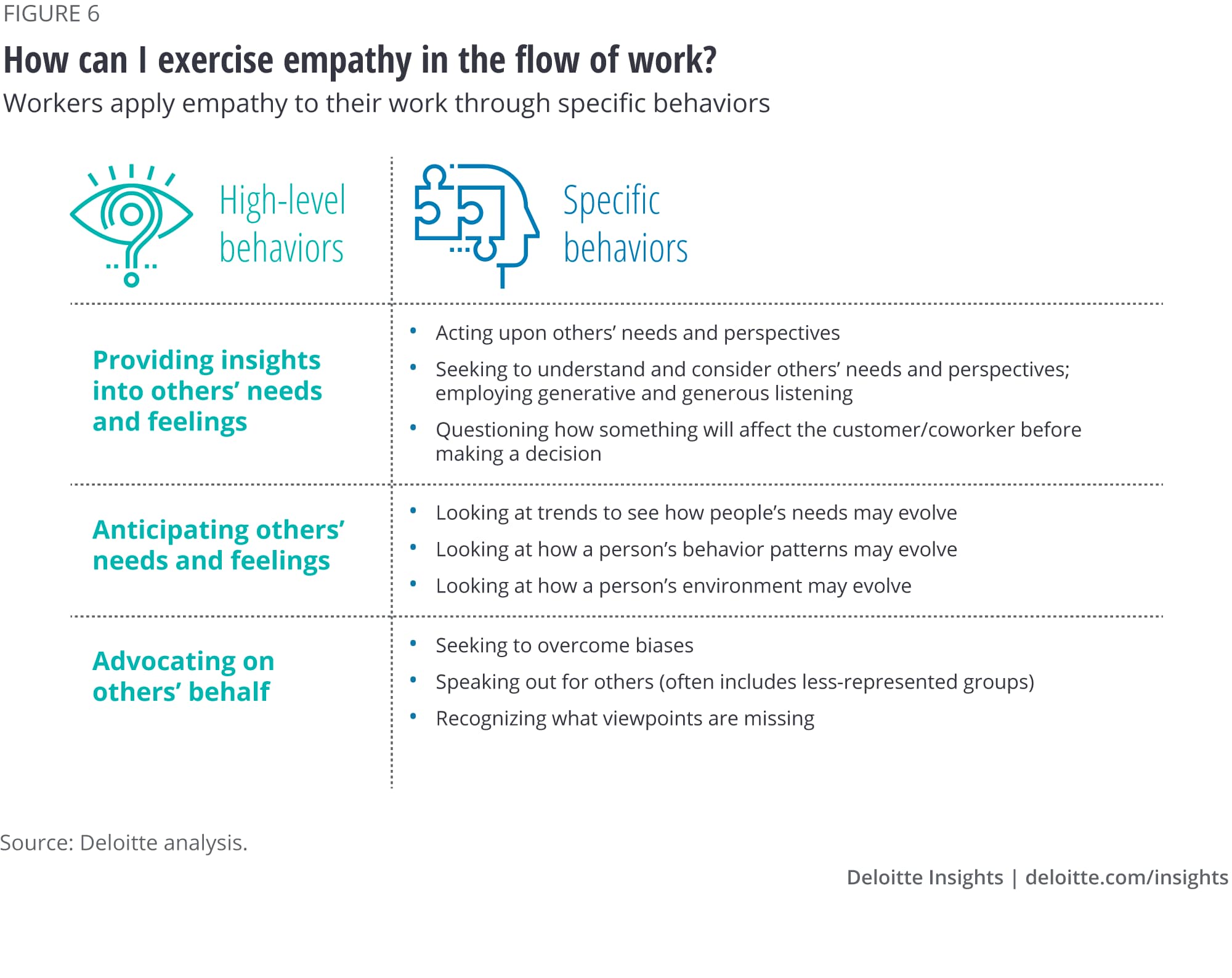

- Empathy is the inherent recognition that others—coworkers, bosses, reports, customers—have different needs, aspirations, and preferences that are informed by the individual’s unique context, which evolves over time based on experiences and personality. It pairs with curiosity, an interest or care that prompts asking What don’t I know or see about this person that might be relevant? In conversations, company leaders often cited empathy as being more essential than the rest, a building block for 21st-century workers; as a cornerstone of design thinking, awareness of empathy has risen. Beyond product development and customer service, empathy among peers and between management and staff can help break a transactional mode of interacting that smooths the way for practicing the behaviors of all of the other capabilities and working more effectively together. Empathy benefits work in three ways (figure 6): Providing insights into others’ needs and feelings helps to understand context that can inform how customers might perceive value; anticipating others’ needs and feelings can reveal opportunities to create new value that the customer hasn’t yet articulated, and how to approach delivering value to them; and advocating on others’ behalf can help the organization oriented on creating real value and meaning for actual customers, partners, and workers.

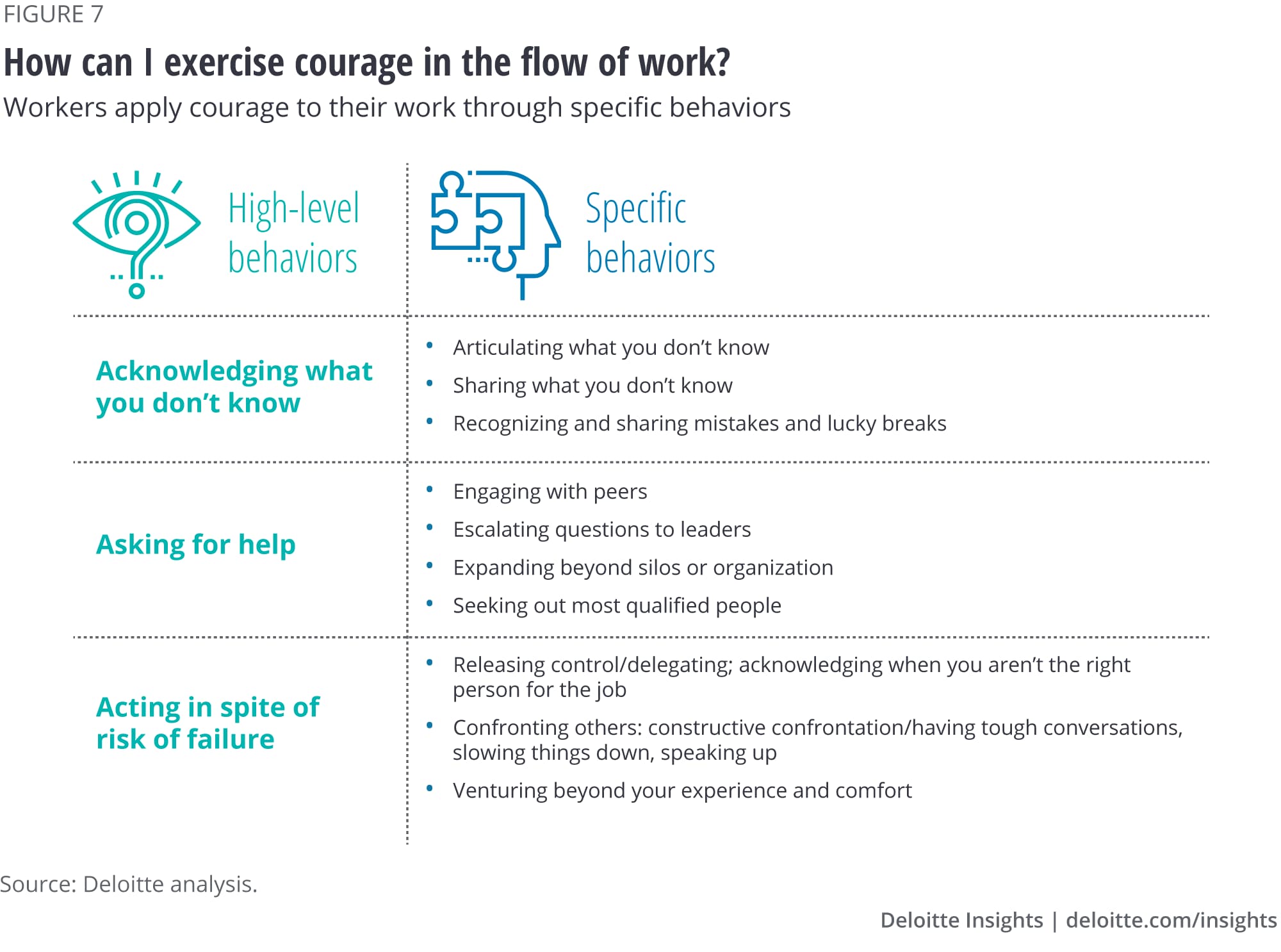

- Courage at work is action-oriented and directed at moving the group toward better outcomes or embracing the personal risk inherent in practicing new behaviors to get better at capabilities. When courage is directed toward meaningful action, in service of achieving something, rather than just directed at overcoming fear, it strengthens itself. In a world with more uncertainty, people may feel real fear around the workplace, results, and performance as well as about their own potential, future relevance, and identity; courage to act is more important than ever. Courage benefits work in three ways: acknowledging what you don’t know, asking for help, and acting despite risk of failure.

In a changing world, capabilities are needed more than ever

The current disruption, uncertainty, and rapidly changing environment have shaken and uprooted long-held beliefs and practices, underscoring how maintaining the status quo is no longer an option. Organizations that have resisted embracing remote work have rapidly adjusted to the new environment or found ways to stagger in-person work. Remote, distributed work environments and necessarily fragmented schedules are shifting and calling into question the relationships between managers and their workers. Many organizations have embraced greater flexibility as workers speak up about increased personal demands and responsibilities. Millions of people are using new work practices and tools and being asked to find ways around set processes and rigid policies. In parallel to these organizational changes, both consumer and business customers are discovering new needs and aspirations, whether an increased need for safety or desire for stability. Opportunities will arise to help make sense of and satisfy these needs.

However helpful they may be now, cultivating capabilities is far more than a response to the ongoing crisis. The biggest opportunity is addressing new value. The crisis has been a catalyst for many organizations to rethink the needs of their workforce and customers; they should also assume that those preferences and the rationale behind them will continue to evolve and change. The internal and external forces that organizations face open the door to the broader opportunity to shift practices and focus on cultivating capabilities.

However helpful organizations may find capabilities now, cultivating them is far more than a responseto the ongoing crisis. The biggest opportunity is addressing new value.

As the world continues to grow more complex and inextricably linked, capabilities will be critical to helping organizations achieve accelerated impact. Skills will continue to be important, but capabilities could be the difference-maker in helping businesses unlock new, undiscovered value. However, cultivating enduring human capabilities across the entire workforce is a largely unexplored opportunity. Few if any companies today focus on the bundle of capabilities—companies that have initiatives to encourage capabilities tend to focus on a single capability and are not driven by the business. Executives have typically focused on more immediate and familiar issues such as speed, cost, and new product development, both because human capabilities (and the benefits from them) don’t seem tangible and because there has been no clear path forward to broadly cultivate these capabilities.

In the remainder of the article, we’ll explore what companies can do to cultivate capabilities.

How to cultivate capabilities throughout the organization

Again, a key reason why few companies work to cultivate capabilities throughout the organization18 is that capabilities themselves may seem abstract, with unclear benefits and no actionable path forward for cultivating them. We’ve addressed the former, why capabilities matter—articulating the benefits to the business—in the first part of this article. In this second part, we will address the latter, how to cultivate capabilities across the workforce, describing both what is required for cultivating capabilities and an approach for acting on it.

Organizations looking to cultivate capabilities across the workforce must both change the broader work environment to address the larger obstacles to applying capabilities and focus on specific behaviors that exercise the capabilities. (Here we’ll look primarily at the significant opportunity to focus on the capabilities themselves, since we’ve written extensively about the work environment elsewhere.) With these two requirements, some have asked, isn’t there a third element? Aren’t the workers themselves most responsible for developing their own capabilities and applying them at work? Indeed, individuals have a role: to bring a growth mindset and willingness to try. The organization can’t provide that, but the environment itself has such a significant influence on motivation, in terms of drawing out and encouraging passion19 and development opportunities, that we focus here on what the organization can do.

Change the environment

Many work environments today don’t encourage workers to apply their curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, or courage to their day-to-day work. True, organizations routinely offer personalized learning journeys, flexible and digital workspaces, collaboration tools, and even programs for everyday innovation. More than a dozen years after Daniel Pink introduced the business world to the power of empathy and play in the “post-information age,”20 capabilities regularly show up in hiring requirements. Why, then, are so few workers called upon to use their capabilities? The rules, processes, technologies, and mindsets engrained in the “way we do business” get in the way. The work environment—including management practices and systems, hierarchies, and the work itself—can create a whole set of obstacles21 that challenge the organization’s ability to cultivate capabilities.

For example, many workers and managers feel a sense of constant urgency; others are consumed by completing tasks and performing to time and efficiency-based metrics. In our 2020 Worker Passion Survey, 83% of workers across levels reported spending more than half of their time on routine, predictable tasks.22 Until they get some relief—time or slack through automating routine tasks, reducing the culture of consensus, refocusing on meaningful metrics—they are unlikely to experiment with a new approach or to step outside the known routine to seek information or unpack a problem’s unseen dimensions.23 As we’ve written about previously, organizations can address time/slack through redefining work itself. By shifting the objective from efficiency to new value and shifting frontline employees’ day-to-day work to identifying and addressing unseen problems and opportunities, leaders clear the way for workers to use their capabilities. Without redefining work, the opportunities to apply capabilities to work will be limited.

Management practices and systems shape the culture and environment in which managers and workers will try to apply their capabilities. Operating in a command-and-control or policing role with administrative responsibilities, the manager may lack time to notice, listen, or coach. If a performance target is the only priority, they won’t make space to hear or encourage workers or to reflect on their approach. When a manager repeatedly fails to respond to a worker’s curiosity or shows no interest when a worker brings up a creative approach, it can kill the motivation to do the sometimes difficult and uncomfortable work of applying capabilities. Micromanagement, lack of trust, compliance-orientation—all can squash the use of capabilities. As new challenges demand new approaches, practices such as managing to budget or quarterly performance management can limit the sense of potential impact and appetite for risk: If my group experiments with our approach, that work will be out of budget or, I’d like to explore the data, but I am assessed on how many reports get filed.

By orienting around frontline workgroups and new business practices, leaders create a structure for diverse groups to engage on complex challenges while also supporting each other’s development.

Rooted in rigid processes and hierarchies, traditional practices may be poorly suited to encourage and support the types of decisions and activities needed to address emerging opportunities and novel challenges. By orienting around frontline workgroups and new business practices, leaders create a structure for diverse groups to engage on complex challenges while also supporting each other’s development. As more and more work moves into workgroups, the manager is freed to support, guide, and connect groups with each other and other resources.24

It’s easy to visualize airy spaces, whiteboard walls, stylish furniture, and stylish people when we talk about a creative or imaginative work environment. But what matters is the integration of physical and virtual to facilitate rather than block flows, the flexibility to continuously shape the immediate environment to the need, and access and visibility to both. Access to information fuels curiosity. Access to others fuels creativity and empathy. Access to experimentation tools fuels imagination. Physical, virtual, and systemic structures can get in the way. While companies push to make L&D platforms available, the systems, tools, and data sets that could support exploration and experimentation in the daily work are often restricted, guarded in a silo, or hidden behind unnecessary title or job-description access requirements.

The workforce may be physically and organizationally too segmented to have conversations that could spur connections or form teams to tackle complex problems. If getting access to a resource or reaching out to others requires approvals, people will stick with what they have and what they know. Leaders can address these issues through redesigning the work environment to foster richer connections, provide opportunities to take on meaningful challenges, and amplify learning and impact.25

Addressing these obstacles (figure 2) to create a more conducive environment is not a prerequisite to beginning to cultivate capabilities, but it is required to sustain them. Unless and until you do, no program will deliver the impact or results you seek. Eliminating or mitigating these obstacles will take time and ongoing vigilance, and leadership should work on them in parallel with encouraging capability-related behaviors.

Ultimately, the success of initiatives to cultivate capabilities will be bounded by the degree to which organizations redefine work to focus on value creation, orient around workgroups, and redesign the work environment to support rapid learning within and among workgroups.26

Change the behaviors (in the work environment)

People, executives to frontline, are generally interested when we talk about applying human capabilities in a way that is essential rather than peripheral to work. But they are skeptical about how they can build capabilities in their own organization. Most struggle with how to make these abstract characteristics tangible. Are they just personality-dependent? Beyond telling everyone to be more creative and covering the walls with colorful posters, how do you know if they are—and what would you tell them if they aren’t? Our research has found that most leaders can’t answer these questions—a key reason why few focus on cultivating capabilities in their workforce.

Our perspective on focusing on behaviors in the work environment in order to cultivate capabilities stems from three insights:

- Effective application of this set of capabilities can’t be trained or taught through familiar types of programs—they emerge from and are developed through the organization’s work under the right conditions.

- Individuals exercise capabilities in the workplace through tangible behaviors in the flow of work.27

- The frontline manager/supervisor or workgroup leader will have the greatest influence on whether and how individuals exercise these behaviors. The manager has the strongest impact on the individual and the day-to-day environment that either draws out and encourages or stifles the capabilities.28

We propose a behavior-centric approach to cultivating capabilities in the workforce. Behavior, and behavioral change, is a more familiar concept, with a wealth of research, tools, and techniques. Through the lens of behavioral change, we can break capabilities into specific work-oriented behaviors that can be made relevant and coached. Behavior and learning models provide further insight around the relationships between readiness, motivation, ability, and prompts29—each of which is unique to the individual in the context of their work and organization—with which a manager can tinker and customize to group needs based on where people are starting from.

To use a lens of behavioral change on cultivating human capabilities in the workforce, we need to translate the capabilities into behaviors that are tangible and also most beneficial to the type of work and the way the business environment is evolving. We defined a set of behaviors for each capability based on the capability’s work-related benefits and the behaviors that would generate those benefits. These target behaviors serve as a manageable set of points that managers can coach, observe, reinforce, and build on with their people. It isn’t an à la carte menu—the intent is that, over time, workers in a group would be exercising all of the behaviors in the flow of work, across all of the capabilities, in order to realize the most benefit.

What follows is a discussion of each of the five capabilities rooted in those behavior sets. For each capability, we discuss how it delivers benefits to business through the specific target behaviors.

Curiosity: Seeking to learn through questions and exploration

The target behaviors in figure 3 are a tangible way that workers can apply curiosity in the flow of work. For example, a worker might question their own current context by taking a mental inventory of the tools and information they typically use to do their work and asking, What other possible tools, data, or resources am I missing? They might broaden horizons by asking what tools other departments are using and looking beyond the organization, seek to learn more about how technology is spawning a new type of tool, or ask how a peer in a different industry approaches a similar type of problem. Individuals might ask questions about the group’s actions and the reasoning behind their approaches: How are we defining success? Is there a better way to do this? Are we aiming high enough? What does failure indicate?

A worker tasked with using a new robot to calibrate assembly machines might ask what else the robot is capable of and, after seeking to learn more about how other companies are using this type of robot, might question whether the current task is the best use of the robot. Ultimately, by seeking to understand beyond what was initially presented on the manufacturing floor, the worker might ask questions and bring in perspectives leading to additional insights and opportunities for the group to deploy the robot on more hazardous and impactful machine maintenance.

Note that questioning the approach is not the same as analyzing a process in search of opportunities to standardize activities—questioning the approach sheds light on the nature of and rationale behind the activities relative to changing needs or requirements. The behaviors that broaden horizons tend to work with imagination to extend beyond the present to better understand context and approaches that haven’t yet emerged. For example, imagine an industrial manufacturer implementing IoT technology in the railyard. The “switchers” (employees that move railcars around) might apply curiosity by asking about what else the technology could do, how different scenarios would be handled, how others were using it, and whether parts of the application could be done differently—their curiosity broadens their own understanding of the technology, providing the spark for future applications of the technology against other challenges. Their questions also expand the implementation team’s perspective and understanding, resulting in a more valuable tool.

Curiosity is foundational, almost prerequisite to applying any other capability effectively, but in practice, it is often misinterpreted to be merely asking questions. Not all questions are created equal, and curiosity-as-questioning goes bad when the questioner peppers colleagues with a never-ending series of superficial or disconnected questions unrelated to the outcome the group is trying to achieve. Another way that question-asking fails is when a leader mistakenly believes the yes/no/status questioning of subordinates equates with curiosity. The target behaviors home in on the types of higher-impact questioning that can help to identify and better address unseen opportunities. Curiosity is enhanced when it is fueled with accessible information and met with interest.

Imagination: Seeing potential that hasn’t been seen before

Imagination may be the hardest capability to exercise. “Failure of imagination” is commonly cited to explain lack of planning or inadequate response to a disruptive but not entirely unforeseeable event, yet people often miss its relevance to their own work. The target behaviors in figure 4 are tangible ways in which people can apply imagination in the flow of work. For example, a worker might identify problems or opportunities that already exist but that haven’t been noticed before by looking at the data sets (software, hardware, other resources) from which they already pull to create a monthly report and playing with possible interpretations of the exceptions to delve into whether the data clean-up they do is indicative of anything beyond disparate data definitions. They might discover that a “known problem” of disparate data actually reflected contradictory policies for the same customers, a frustrating problem that the customer satisfaction surveys never surfaced.

Imagination also looks beyond the bounds of the immediate to see how new types of problems and opportunities might emerge—for instance, if a defining assumption or boundary were to change or a seemingly fixed relationship hierarchy were flattened.

A worker in a food processing facility might first notice how the switch to electronic driving logs was affecting truck drivers, consider how potentially fewer long-haul truckers might affect the speed of getting the highly perishable product to market, and play with ideas for how different packaging or staggered processing might help address such a problem. Many fundamental shifts in consumer behavior, such as the shift from DVD to streaming, seem obvious in hindsight, but in the moment, it can be extraordinarily difficult for individuals at any level to envision an environment that doesn’t yet exist.

Finally, imagination can identify new forms of impact or value, even or especially when whatever we’re doing now is successful. Conversations with customers might lead a retail cosmetics worker to explore whether the company’s segmentation of customers by age is missing the way certain groups across segments prioritize “clean” products while other cross-segment groups prioritize novelty and social good and others convenience and dependability. She might talk with colleagues about the ways different types of customers are evolving and play with what other types of value they might demand as their priorities and aspirations change. The National Basketball Association identified new value with—the “Elam Ending” in the 2020 All-Star game: By changing the rules governing late fourth-quarter play, the NBA discovered how much fans, and players, valued excitement and unpredictability in a mature product.30

Creativity: Innovating new approaches; using resources in unexpected ways

Figure 5 shows the target behaviors associated with applying creativity in the flow of work. In the construction business, for example, site managers may see the need for new approaches on complex projects and recognize obstacles such as incompatible stakeholder agendas, diverse subcontractors, environmental concerns, and regulatory issues.31 They might work with peers and across subcontractors to frame and design new approaches, from rethinking the staging order to using new technologies to fabricate most of the building offsite.32

Developing new approaches and mobilizing others around them can be difficult when there is a strong precedent for how an organization has done something in the past and a belief that there is only one right way. Tinkering on the margins can yield benefits, but greater benefits come when workers are experimenting and evolving the approach with the explicit intention of having more impact. Consider the wide range of customer experiences and satisfaction with grocery stores, a competitive industry in which some companies have notably focused the frontline on engaging directly with customers and constantly trying out new approaches to deliver value to the local and specific customers, while other companies try to manage thin margins through hewing to strict policies and a uniform approach.33

Empathy: Understanding and considering others’ feelings, experiences, needs, and aspirations

The target behaviors in figure 6 are a tangible way to start applying empathy in the flow of work. For example, a hotel check-in clerk faced with a demanding guest one evening might perceive irritation in the facial expression but then consider that the customer was supposed to have arrived that morning and that they were alone despite booking for a couple, and reread the guest’s expression as disappointed and exhausted. The clerk might develop a streamlined late-night check-in procedure and pre-arrival turndown service with the “exhausted, disappointed” traveler in mind.

Empathy’s value extends well beyond product design. When workers put themselves into others’ shoes, they can look at broad trends or plumb data sources for individual behavior patterns to consider how a customer’s behavior or environment might evolve—and the implication for needs and preferences the customer hasn’t expressed because they don’t yet exist. Workers are often more motivated and feel more satisfied when they have greater insight into others’ perspectives and needs and are speaking out and advocating for those needs in situations where those voices are not present. At the Morning Star Co., a study found that tomato harvesting teams took more care and found new ways to deliver higher quality yield after seeing videos where the downstream sorting crew—coworkers with whom the teams never directly interacted—discussed their on-the-job challenges.34 In numerous companies, we have heard stories in which finance or IT staff were surprised and then inspired to better address a need, when they asked their internal customers about their work and what value they actually needed, whether from a budget report or a particular app.

The manifestations of empathy toward coworkers are relevant not only in high-intensity environments such as at a tomato plant or on a manufacturing line but in seemingly minor interactions during work. Recognizing which viewpoints aren’t present in a meeting, and being able to speak on their behalf, provides a richer understanding of context and enables a wider range of possible ways to better address a problem or opportunity.

Courage: Acting despite uncertainty or opposition

Figure 7 shows some of the tangible behaviors associated with applying courage in the flow of work. For example, consider a customer service workgroup that from consumer data they collected realized their group’s value would diminish in two years due to changing customer preferences; rather than cover it up to pursue current successes, they were transparent with their insights, giving the group the opportunity to pivot. Instead of trying to problem-solve in a silo, a customer service agent shared the insights with sales and sought that function’s perspective on the different skills that would be valuable for selling to tomorrow’s customers.

Another way the front line shows courage is by asking for help, including in public settings such as an executive town hall. For example, a worker who stands up to ask an executive for training might reveal a serious, and previously unseen, lack of managerial investment in the third shift despite leadership’s belief that it was a critical part of achieving the operating performance required for a new market. Escalating beyond the chain of command can be powerful and motivating to others because it demonstrates a commitment to the group’s outcomes as well as a willingness to grow and develop. While one employee’s behavior won’t likely lead to a complete overhaul of the culture, it can add credibility and tangible urgency to initiatives already underway and inspire peers to question and act. Fear and perception of risk are very personal, and the behaviors of courage, more so than the other capabilities, will vary significantly depending on the individual.

What to do: How do you approach this?

In our research, many leaders shared that the imperative for capabilities might be clear but what, if anything, they can do about it is far murkier. The following approach is based on the understanding that cultivating capabilities to be applied effectively in day-to-day work has to occur in the flow of work rather than in training programs. The approach centers on the idea that employees apply the capabilities to work through tangible behaviors adapted to the work environment.

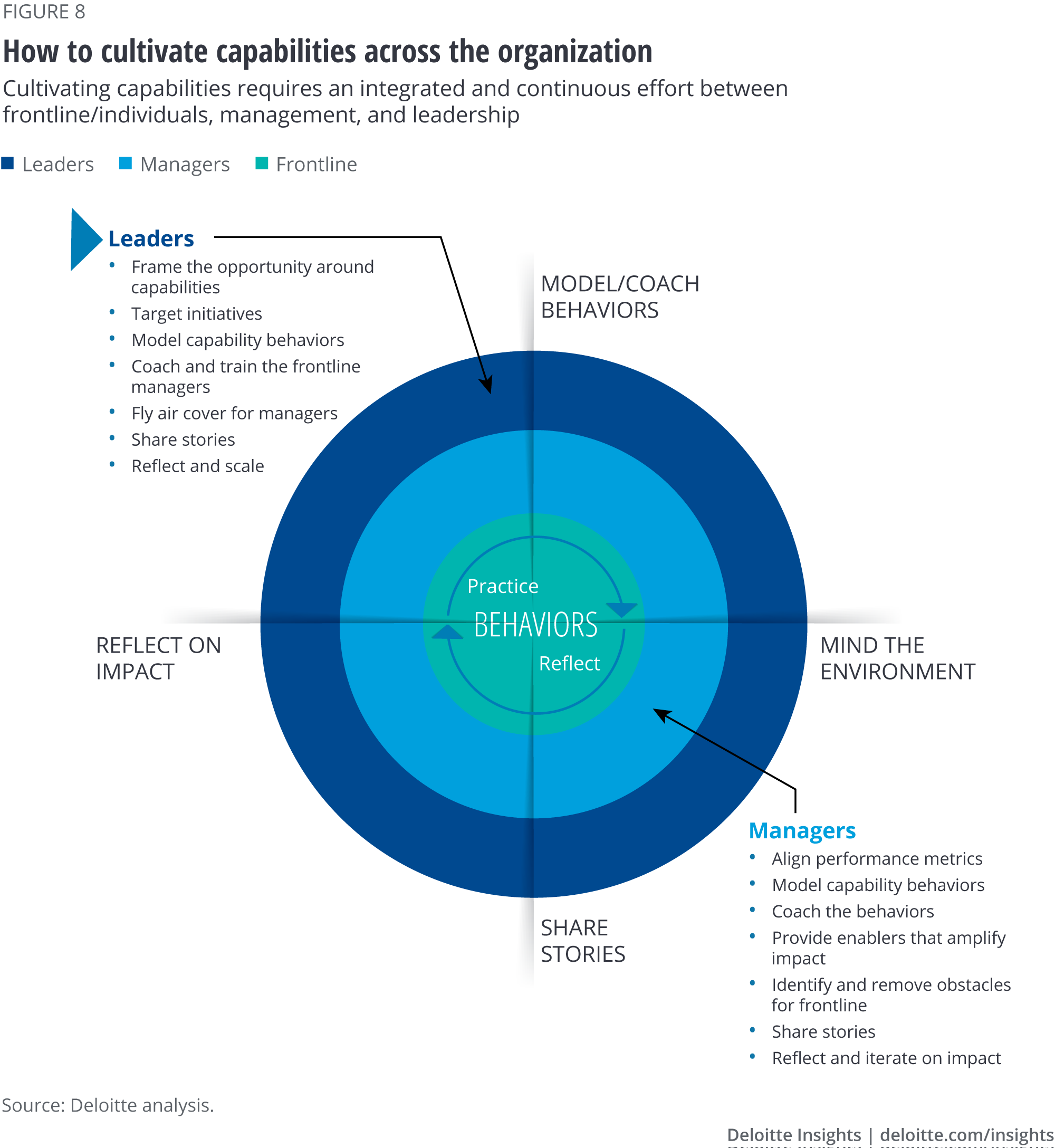

Figure 8 outlines the critical roles that each level of an organization plays in cultivating capabilities. The goal is to eventually have workers at all levels across the organization applying the capabilities in their daily work and developing and strengthening them over time. To improve at using and strengthening capabilities and behaviors across the workforce, leadership, managers, and individuals must reinforce each other across levels. Each has a role to play in supporting and reinforcing the capabilities. The frontline manager/supervisor will have the greatest influence on the individual and the day-to-day environment that either draws out and encourages or stifles the capabilities.

While cultivating capabilities does not require sweeping transformations or seismic changes, it will require coordinated efforts focused on behavioral change and time investment from all parts of the organization.

Leaders

Leadership lays the groundwork for cultivating capabilities and also reinforces their importance and supports their success in the organization. Ultimately, leaders facilitate an organizational change in mindset, and it is up to them to adopt a new and different approach for unlocking workers’ potential. Cultivating capabilities requires an integrated, consistent effort across all levels of the organization—leaders, management, and frontline—until it becomes ingrained. Broadly, leadership needs to focus on activities that make cultivating capabilities successful and that sustain over time. These activities include framing the opportunity, picking initiatives (where to start and subsequent), developing the coaches, identifying the metrics that matter, removing obstacles, and reflecting and scaling the shift to capabilities. Framing the opportunity and picking the initiatives come first, but the rest of the activities have no defined order and should be ongoing without a definite endpoint.

Frame the opportunity. Leadership must believe in the value of capabilities across the organization and frame the impact that capabilities can have on the business. This framing, and the leaders championing it, set the opportunity in motion through a compelling vision: What is the opportunity, and why are capabilities necessary to achieve it? The framing is based on leaders having a clear understanding of why the switch to capabilities is a major shift and why the status quo must change, as well as how human capabilities are necessary and will help the workforce achieve much more impact than they could without them. A compelling vision incorporates the rationale while focusing on the opportunity.

The vision becomes more credible and compelling when leaders make the vision tangible through their own example. Consider how the executive leadership of a company with a deep culture of execution and achievement might realize that what got the organization to that point was less suited to the rapidly changing environment, and that the company needs to become much more curious and empathic. To frame the significant shift required, the executive team needs to communicate a vision and a compelling rationale about a significant pain point across the organization, such as why they are losing out in the talent war or why they are losing customer loyalty, rather than about capabilities in the abstract.

Consider what stories you are telling organizationally. Do they explicitly honor and reinforce that capabilities are critical to the company’s future? The Morning Star Co., for example, has an organizational parable around an independent truck driver who, in striving to increase output and load size, challenged the big tomato processors and used his curiosity and creativity to alter manufacturing processes. Sharing stories from across the company—about a salesperson using empathy to create a memorable moment for a desperate customer in the store, or a set of curious questions leading a data analyst to a new revenue opportunity—can motivate and provide some direction and how-to. They also reinforce that “something new is expected of you and it will have an impact.”

Awareness can be built up through storytelling and reinforced through simple prompts. Something as simple as a manager asking, “What did we learn about a customer that we didn’t know yesterday?” signals that the organization values empathy. Other companies adopt a set of questions, shared by management and the front line—What if? Why? How might we?—that boost awareness and a practical starting point to use their curiosity.

Leaders should continue to refine the framing to be relevant and compelling for their people and also more specific to the groups where they choose to start.

Consider what stories you are telling organizationally. Do they explicitly honor and reinforce that capabilities are critical to the company’s future?

Pick the initiatives. Start small, with two target initiatives or groups. The end goal is for the entire organization to be applying capabilities to all of the work, but a large rollout before benefits have been demonstrated will likely generate resistance.35 One of the starting initiatives should be in the core business and the other from the organization’s “edge.” The reason for choosing one of each is that focusing first on an “edge” product group can send a message that capabilities are relevant only in certain places and leave the workers in the core feeling disenfranchised and unmotivated around capabilities.

When choosing where to start, assess both where cultivating capabilities can have the most impact and where an initiative around the behaviors of capabilities is most likely to succeed.36 Is there a supportive key sponsor? What level of impact can that group have? Will the group have high receptivity? Often, groups in which capabilities have been lacking or dormant will likely see the greatest impact from their introduction, so although it may be counterintuitive, avoid starting with R&D teams that already apply creativity and curiosity, and similarly, avoid starting in product design teams that already employ empathy through design thinking. Not only are those types of groups less likely to show the most significant impact from capabilities—they may also be less receptive and take an attitude of “already doing it, nothing new here.”

In addition, the receptiveness of the frontline managers or supervisors who will be involved is key. There’s no point in starting out with a group in constant crisis or suffering from a toxic climate of micromanagement and distrust—capabilities could prove helpful there, but the manager must be receptive and have an orientation toward building relationships and supporting and developing the people in their group. To make that initial effort feel warranted, consider groups that have a significant pain point they have struggled to address. Once leaders select where to start, they’ll need to further frame the impact for the two groups by tying the organizational vision for capabilities to the groups’ shared outcomes and goals.

Develop the coaches. The managers and frontline supervisors of targeted groups will need training and additional support to effectively coach their teams in the behaviors to use capabilities. This “coaching the coaches” will take place after the two pilot groups are chosen, and part of it will be the leader further framing the opportunity for the managers in ways that are specific and meaningful for their groups’ work as well as for the managers in their growth and development.

For the shift to capabilities to succeed, managers must understand the types of benefits that leaders expect to get from capabilities as well as how those benefits relate to their groups’ work and goals. The managers will be the ones coaching and encouraging the workers in the behaviors. Through their own actions and attitudes, they create an immediate environment where workers will be adopting the new behaviors or not. The managers will provide the guidance and rationale that gives their people direction and motivation to try to exercise the behaviors in their day-to-day work. Managers need to understand and be enthusiastic about the opportunity, but they must also be able to communicate the vision and behaviors in a relevant, clear, and compelling way.

The training will also provide guidance on capability behaviors. Since the concept of behaviors will most likely be new, managers will need a foundation of how the behaviors relate to the expected benefits on their groups’ work. As discussed earlier in this section, each capability is applied to work through a set of behaviors. The managers/supervisors will need some preliminary guidance on what the behaviors might look like and what boundaries or unwanted effects they might need to pay attention to given their industry, region, working conditions, or workforce characteristics. These trainings should be intimate, interactive discussions focused on the managers who will be involved in the upcoming initiatives, not a companywide program rollout.

The managers will be the ones coaching and encouraging the workers in the behaviors. Through their own actions and attitudes, they create an immediate environment where workers will be adopting the new behaviors or not.

Identify the metrics that matter. Most organizations will pursue capabilities to improve organizational performance, not for their own sake or to make workers feel more satisfied. To gauge the level of impact and the success of the initiative, leaders will need to identify each group’s meaningful operating metrics—the metrics that matter. This starts with identifying a meaningful area of performance for the organization, likely related to growth. From this, what are the key operating levers that drive that performance, and in particular, are there operational pain points the organization has struggled to solve? This is impact that will matter to the organization, the type that will generate interest and momentum for others to cultivate capabilities. The operating metrics that matter must be leading indicators of performance, providing impetus for action to make course corrections in real time rather than in retrospect. The operating metrics also need to be something the chosen starting workgroups or teams can influence—the shared work outcome or the reason the group exists. If the operating metric isn’t something the group can control, either find a different metric or a different group to start with.

From the operating metric, identify lower-level metrics—again leading indicators—that tie to the groups’ work and performance objectives that account for what they are capable of with the release of workers’ curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and courage. This process should not be leadership handing down metrics to the frontline supervisors but, rather, an iterative discussion to arrive at metrics that are meaningful to both the organization and the workers and that are within the control of the workgroup. More important than an absolute goal is a trajectory—getting better, faster. Setting high-impact performance objectives and tracking the trajectory of their improvement can help the group invest in the effort to apply capabilities in order to achieve better and better outcomes instead of settling for the standard approach and limited gains.37 Capabilities should enable the groups to start increasing their trajectory. Leadership needs to work with managers to further clarify these metrics at the group level and explore how to shift away from or work with current metrics.

Fly air cover; remove obstacles. Cultivating capabilities in the workforce is an ongoing process, part of how work gets done. Leaders’ role is ongoing as well, supporting managers and supervisors, systemically eliminating major obstacles and managing the workforce tensions and resentment that arise anytime change is present. For the initiative to be effective, leadership needs to stay vigilant to the needs and obstacles that frontline managers face on a day-to-day basis and provide the tools, resources, and support that management needs to address them. As we have discussed, for the capability muscle to be exercised, major obstacles need to be eliminated by redefining work and redesigning the work environment; while there is some overlap, there are additional obstacles around the capabilities and the behaviors on which leadership needs to be able to continuously act. Our performance is up—who cares if they aren’t using capabilities? What does imagination mean for our IT team? I’m not sure my team is really exhibiting the behaviors even though they are saying they are.

The final piece is to manage workforce tensions. How can leadership reconcile the impediments to cultivating capabilities and stay the course? For example, if the business has a couple of bad quarters, the business owners may tend to default back to business as usual and away from the capabilities. In order for capabilities to take hold, leadership needs to double down with support and direction.

For the initiative to be effective, leadership needs to stay vigilant to the needs and obstacles that frontline managers face on a day-to-day basis and provide the tools, resources, and support that management needs to address them.

Reflect and scale. Finally, leaders should reflect on pilot groups’ successes and failures, with teachings as guideposts for scaling the cultivation of capabilities. Leaders should be reflecting on workgroups’ performance, looking at the metrics that matter to see whether they are making the intended impact. Leaders should also reflect on their approach to choosing the initiatives and the management coaching. They can reflect on their assumptions going into the whole process: what still holds true and what has changed, and whether training was adequate. They should also be taking feedback from managers as part of their reflection process. These insights should guide leaders on their path forward as they try to scale capabilities to other parts of the organization.

Finally, however difficult it is to imagine a useful measure of what level of a specific capability an individual has, or how the organization would interpret that level, leaders need some way to monitor how the organization is doing, capabilitywise. In our research, while we found some companies attempting to assess for a capability in hiring, and a few in development and promotion decisions, none were tracking whether their work and work environment were cultivating or destroying capabilities. Don’t expect an absolute measurement—these capabilities applied to work are constructs, unique to each organization’s interpretations.

To supplement the ongoing reflection described above, assessment could take two forms: perceptual surveys for frontline employees and managers and behavioral assessments built on real work situations. The first is fairly easy and could be run frequently and broadly to provide a general health check and highlight trouble spots. The second requires more effort to create relevant work-based test environments and actionable behavior evaluations but could potentially provide a richer understanding of capabilities in the organization.

Managers

The frontline manager or supervisor is central to cultivating capabilities. They can do this primarily through coaching and reinforcing the target behaviors and creating an environment where their people feel the permission and expectation to use the behaviors in day-to-day work. It is the individuals who will adopt behaviors or not and who will put in an effort to deepen their capabilities or not. The manager can make the behaviors easier to do and try to increase workers’ motivation.

Cultivating capabilities is the ongoing job of managers, not a time-bound initiative. The role of the manager is to align around performance metrics, coach the behaviors, identify and remove obstacles, provide enablers, and reflect and iterate.

If the behaviors become entrenched in the “way we work,” managers’ jobs will be easier in some ways: People will use empathy to resolve conflicts with coworkers; their unleashed curiosity will motivate them to dig deeper to understand problems or needs, do more than the bare minimum, and expand their knowledge base; they will be more able and likely to use creativity to tinker with approaches and find their own solutions to bottlenecks; and as workers become more confident with the behaviors, they should feel more invested and interested in their work.

What does success look like? Ultimately, managers cultivate capabilities in order to achieve more impact or deliver more or better of the group’s work outcome—what impact or value are you trying to create? At the same time, the initiative’s goal is to focus explicitly on the capabilities as a means of achieving better outcomes. So, managers should assess success according to progress on both fronts.

Being clear about the dual metrics and the broader impact for the organization can provide guidance and help make exercising target behaviors less risky. However, target behaviors must be shaped and made relevant to the personalities and characteristics of the immediate group, the manager and leaders, their interactions, and the work itself. Managers will need to be able to articulate the goals and outcomes and lead the way by modeling the target behaviors themselves.

Align around performance metrics. As noted in the identify the metrics that matter section, leadership defines what higher-level operational metric to target. Working with a leader, the manager must identify a related but more granular metric to target and make the metric clear and meaningful to the workgroup or individuals, taking into account the nature of the work and the conditions and environment within which they work. The metric should be tied to a workgroup’s shared outcome and may need to be translated into something more relevant for individuals who work more independently. Make sure everyone in the group understands what defines success in terms of performance as well as expectations for how the capabilities will help them achieve better performance.

A meaningful metric serves as a touchstone. It can reassure workers and show them results when they feel uncomfortable or uncertain about the impact of behaviors, or it can prompt reflection and course-correction if the behaviors aren’t having the desired impact.

If the workers have been very task-focused, aligning on metrics is an opportunity to hold a broader discussion about changing expectations for the work they do and how they do it. Part of making the metrics and the initiative relevant for workers is for the manager to sit with their people and talk about what “value” and “unseen problems or opportunities” might look like in the context of the work they’ve been doing and are expected to do.

Finding the right metrics to monitor and demonstrate impact builds credibility and momentum. The relevant metrics give you a sense of whether you’re creating more value: Number of solutions implemented, customer renewals, or net promoter scores might be good places to start. Call duration or production-line downtime might provide useful information for monitoring operations but lack context that gives insight into value or impact or opportunities to deliver more.

Coach the behaviors. Coaching workers requires continuous effort and may be an unfamiliar role for many managers. It starts with the target behaviors. Managers make the behaviors relevant to workers and help them practice until the behaviors become their default mode at work.

Rather than having all the answers, the manager-as-behavior-coach helps individuals reflect on their progress, find productive ways to adjust, and stay motivated and accountable to keep trying the behaviors. Coaching is more observation and critique than monitoring and criticism.38 In particular, the discussion focuses on where and how target behaviors can move the needle on the group’s more granular performance metrics. As behaviors become engrained, some individuals can become more adept and confident. Others will make missteps that surface unintended consequences or misunderstandings that need to be addressed.

For a manager coaching the target behaviors, it’s useful to consider what levers can help or obstruct an individual taking on a new behavior. The Fogg Behavior Model simplifies these as ability (Are they able/know how to do it?) and motivation (Do they want to do it?). The two can work together or offset each other. Really hard things need more motivation to attempt—either find the motivation or find a way to make the behavior easier.39 Often management goes straight to motivation, mostly extrinsic, with incentive systems or penalties to drive adoption. Motivation is fickle, though, unique to the individual and subject to change in unexpected ways. Managers would do well to focus on the intrinsic motivation that comes from shared outcomes, awareness of why and how capabilities matter, and the sense of meaning and passion that comes from being able to take on meaningful challenges with others. Equally, managers should try to make behaviors easier—through guidance, tools, and coworkers.

Lack of awareness about how capabilities would be valuable in a given context can work against confidence, further squashing motivation. For example, a customer service agent who gained new insights from talking a customer through her frustrating experience with the payments platform might not share at a team meeting because their empathy and curiosity were in support of their own metric—customer satisfaction—and it doesn’t occur to them that others in the organization might find insight into a specific customer useful. Staff accountants might not see how imagination or empathy could create any value (or even be allowed) in their work in a way that is still consistent with legal and regulatory requirements. Sharing stories of how other colleagues used a behavior can give a sense of how-to.

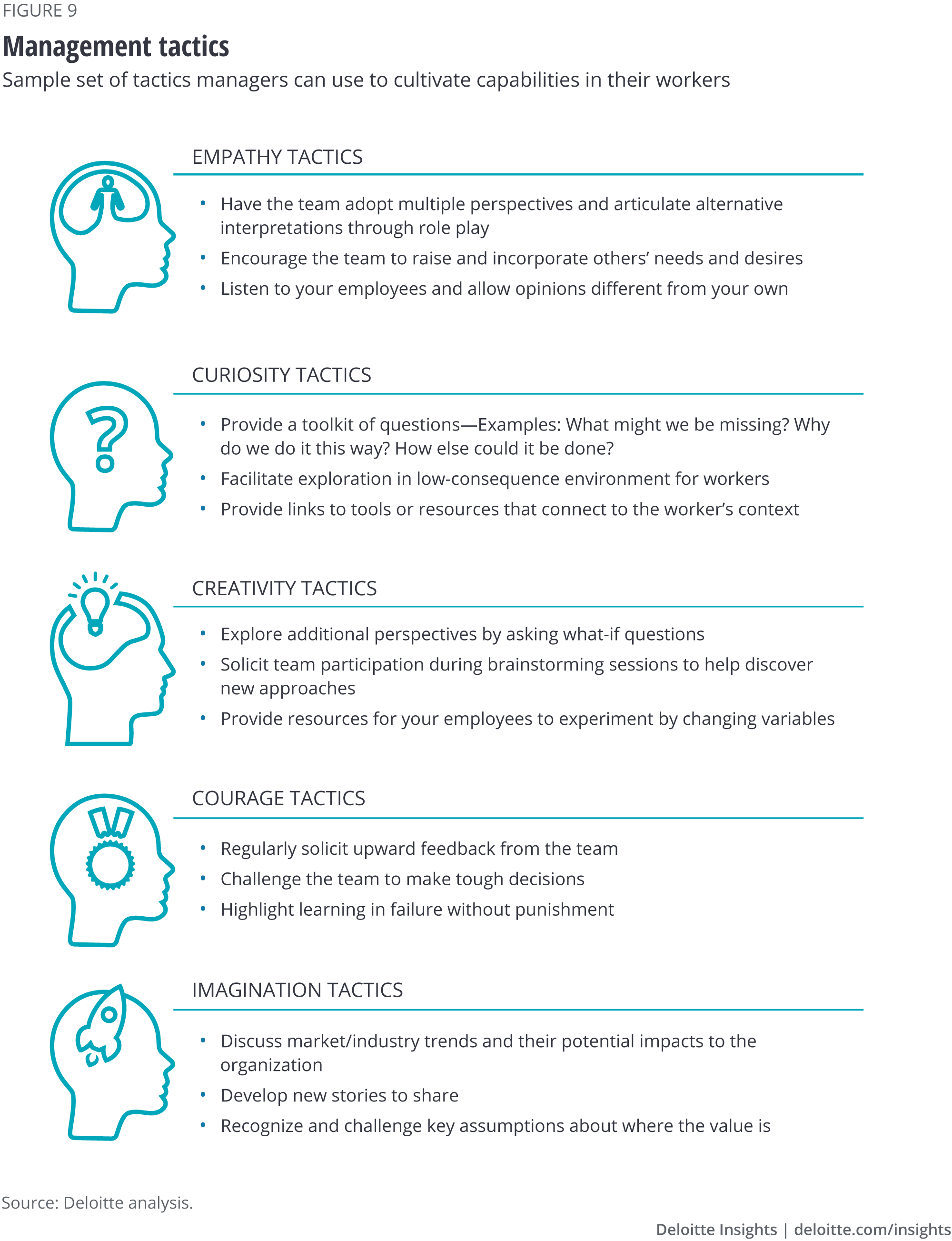

The guidance needed and the best way to deliver it will depend on the company’s environment and norms and where workers are starting from. Figure 9 shows a set of tactics that managers might find helpful as a starting point for making behaviors easier to attempt and understand. Success with a tactic also can generate a sense of accomplishment that boosts motivation.

Consider an IT support team struggling to “anticipate the needs of others” (empathy). The manager might have a team member debrief a challenging interaction with an internal client and lead a discussion to identify clues as to what the customer might have been feeling and create a story about what her day might have been like leading up to and after the encounter. The manager might direct someone to explore a data set that includes the customer’s interaction events with IT and guide a discussion about what interpretations they now draw about how a client’s needs, behavior, and environment may evolve and how they arrived at those conclusions. Alternatively, a manager might encourage a worker to ask more questions of clients about the type of work they do and what they find most challenging, or even invite a few internal clients to come to a “how I use IT break” to share with the team what their parts of the business are doing and the role technology plays in their day. All of these can help prompt or support the behaviors associated with empathy.

Identify and remove obstacles. Leaders should be working to eliminate the larger systemic obstacles, but new stumbling blocks, of varying scope and significance, will inevitably emerge. Awareness and perceptions, lack of time, the unintended consequences of management practices, and the inability to access tools or have visibility all manifest at the group level. Some will be hyper-local—a team that suddenly becomes, after a highly visible success, too risk-averse to seek help from beyond the group. Some will be companywide or external—the company’s stock falls on earnings and new performance targets are pushed down—and might need help from a leader to mitigate or provide cover. Unforeseen problems and complications, as well as opportunities, will pop up, and others will simmer—the manager has to stay diligent to the group dynamics and work environment and pay attention to how they affect the target behaviors. Comparing notes with other supervisors and managers, particularly peers in a capabilities initiative, can help managers recognize obstacles and get help addressing them.