Skills change, but capabilities endure Why fostering human capabilities first might be more important than reskilling in the future of work

15 minute read

30 August 2019

Amid continuing skills shortages, a focus on cultivating underlying human capabilities such as curiosity and critical thinking can give companies a sustainable source of the talent they need.

At some Toyota plants, new workers don’t learn how to operate or feed materials into a specific piece of machinery. Instead, they spend weeks, even months, learning to do by hand what machines do so much faster.1

Introduction

What’s going on? Is Toyota going backward on automation? Far from it. Toyota, long known for the Toyota Production System—which has been described as “less a manufacturing system than a distributed problem-solving system”2—is putting its workers to hands-on, slow labor, not because it plans to revert to manual processes, but because its leaders believe that people grow in valuable ways when they viscerally experience the transformation of materials into parts and parts into assembled vehicles. Starting from scratch prompts workers to appreciate the materials they are using and the way those materials interact with various tools and techniques. More than this, the very process of learning to build a car by hand forces workers to draw upon qualities such as imagination, creativity, problem-solving, and experimentation. The intent is to arm these workers with the right capabilities to enable them to continue to ask the right questions of unforeseen problems and develop new solutions—including ways to improve the automated processes—amid the ever-changing sets of technologies in use on the factory floor.

Learn more

Read more from the future of work collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Toyota’s approach may be counterintuitive, but it holds an important lesson: that while the skills to operate any given piece of machinery—or, more broadly, to carry out any given task—will inevitably become obsolete, the capabilities to understand the context, to tinker with alternative solutions, and to develop and creatively apply new amalgamations of techniques to achieve better results endure beyond any new technological advance or marketplace shift. Further, these capabilities will likely become even more important as companies across the economy face a shift in demand away from standardized, mass-market offerings. Effectively understanding customers’ dynamic needs and addressing them with more personalized offerings will require a workforce capable of reading and responding to specific needs and conditions with novel approaches.

The kinds of universal human capabilities that we’re talking about transcend specific skill sets and domains. Indeed, they underpin an individual’s ability to gain specific skills—when, where, and how they are needed—in the first place. At a time when skill needs are changing ever more quickly, and headlines feature looming skills gaps and obsolescence, a focus on cultivating underlying essential human capabilities can give business leaders a sustainable way of finding the talent they need.

Skills are valuable, but they’re not everything

We define skills as the tactical knowledge or expertise needed to achieve work outcomes within a specific context. Skills are specific to a particular function, tool, or outcome, and they are applied by an individual to accomplish a given task.

Most companies’ relentless focus on skills is not surprising, given the general sense that businesses need new skills and that things are changing so fast that people can’t keep up. Their concern stems from the conviction that skills—and having workers with specific skills—are core to business success. But while they’re not wrong, skills aren’t all that are core to success these days. The marketplace and technological environment are changing in ways that make focusing on skills to the exclusion of all else a losing approach.

The reason skills have been so valuable and necessary is because, through much of the 20th century, businesses depended almost wholly on skills to get work done. But the reason they could afford to depend so entirely on skills was because they operated in a specific type of environment: a stable, predictable one in which companies could use standardized, repeatable processes and techniques to produce standardized products and services on a controlled, predictable schedule and budget.

In this broad, stable context, executing repeatable activities in standard environments was the most efficient and effective way to serve ever-larger markets by meeting the greatest common denominator of need. With relatively few different types of products being offered, a given skill could be widely applied; too, the skills needed were predictable and did not evolve very fast. Thus, it made sense to invest in training large groups of workers in these widely applicable skills. In addition, well-honed skills helped companies operating at scale to do things more predictably, more quickly, with less waste, and at lower cost.

That’s the world we were in—but the world is changing. The connected world has made scale less important than relevance, and the strategy of optimizing for scale can no longer deliver the results we need.

Investing relentlessly in skills is yielding less return

It might seem that, in today’s environment—with the acceleration of technology driving new needs in new domains that demand more and more varied skills3—businesses should simply redouble their efforts to train workers on the required skills. But, paradoxically, focusing on skills alone isn’t the answer to building the workforce needed for the future. The reason is twofold. First, because of changing customer expectations and the pace at which technology is becoming able to replicate human skills, the number and variety of skills required to serve a profitable market is growing faster than the workforce can learn them. And two, skills themselves are becoming less central to creating the type of value that will differentiate a company and help it build deep, long-term relationships with customers.

The long accelerating trend in digital technology performance (and resulting advances in other technologies) has fundamentally reshaped the marketplace. Individuals have tended to more readily embrace new technologies than traditional businesses and institutions, which often lag behind.4 This has changed customer behaviors and expectations in ways that have made value creation for the customer more important, rather than just cost minimization or profit optimization for the company. This, in turn, has created an environment where, for many companies, the return on investment in developing skills among their workforce is decreasing.

One major reason for this is that customers today have higher and more varied expectations, fueled largely by the access to information afforded them through digital technology. Standardization is giving way to personalization as consumers, able to select from potentially dozens of options instead of just one or two, seek out exactly what they want rather than accept a mass-marketed approximation. On the other side of the fence, technology has enabled businesses to more easily cater to consumers’ expectations for personalization: New business models are arising that allow companies to make and deliver those offerings quickly and on demand. As a result, consumers are expecting more and more personalization across product/service categories and in more arenas of their lives.

Consumers’ expectations for personalization have a ripple effect throughout the company. For instance, operations, including some back-office activities, will likely need to become more context-specific to support the development and delivery of highly personalized products and services. The shift toward personalization will also affect the business-to-business world, where standardized offerings may be less relevant to corporate customers oriented around delivering personalization to their customers.

Greater variation in products and services implies that a greater number of different skills must be brought to bear to develop, market, and deliver them. At the same time, the set of skills needed to satisfy any particular buyer is becoming more narrow, changeable, and specific. The upshot: It no longer makes economic sense to train a large number of workers on a few generalized skills, expecting them to then be able to use them broadly to create and deliver a great many standardized products. Instead, companies are finding themselves in the position of having to train their workers to master a great many specific skills to create and deliver innumerable variations of a tailored product or service—which is rarely as cost-effective as the former approach. The tendency of companies to develop large training programs that generalize skills in order to train the greatest number of workers only makes the investment harder to justify. Without context, the skills being taught are mostly inadequate to the types of challenges for which they are needed.

In addition to demanding more personalization, customers have become more powerful in their relationships with businesses. We’ve documented a long trend toward decreased brand loyalty due to greater transparency into options and lower switching costs—both of which, again, stem from advancements in digital technology.5 Consumers know more about a product or company and can easily access options beyond the mass market. They can also quickly compare notes, identify discrepancies, and mobilize action when they don’t receive the value they expect. This power means that markets are not only more fragmented, but also less predictable, consistent, and durable than they used to be, again reducing the applicability and the longevity of any given skill.

Compounding the effects of these two factors has been that technological advances have allowed more and more skills to be automated—by machines that can learn them much more quickly and perform them more reliably than humans can. That’s not a race humans can win, even with elaborate reskilling programs. From artificial intelligence to robots, technology has become increasingly able to pick up the types of technical and scientific skills that once would have seemed to be squarely in the human domain: eye surgery, lab diagnostics, picking and packing grocery deliveries, or even making a pizza. In addition, emerging technology also makes certain tasks obsolete: When processes are redesigned to better fit new technology, it often eliminates tasks that were essential to the old process but unnecessary to the new.

Given these changes in the marketplace and in technology, it's no longer possible, by and large, to compete based on standardization and scale. Indeed, many big producers are being eaten away by an increasingly fragmented set of little guys who can better adapt to the modern customer’s expectations for value. In this environment, companies won’t be able to satisfy customers through offerings designed to maximize efficiency for the company without accounting for the customer’s evolving needs. They won’t have a choice but to find a way to equip their people, not once but on an ongoing basis, with the growing number of increasingly specialized skills needed to serve today’s markets.

The good news: It’s time for capabilities to come to the fore

Many reports paint a grim picture of jobs lost and workers made irrelevant if they can’t learn new skills—as well as of factories going silent and businesses bankrupt if they can’t find enough workers with needed skills. However, this focus on skills misses the point. In an economy that desperately needs more and more new skills, refreshed more and more often, what becomes most important are not the skills themselves but the enduring human capabilities that underlie the ability to learn, apply, and effectively adapt them.

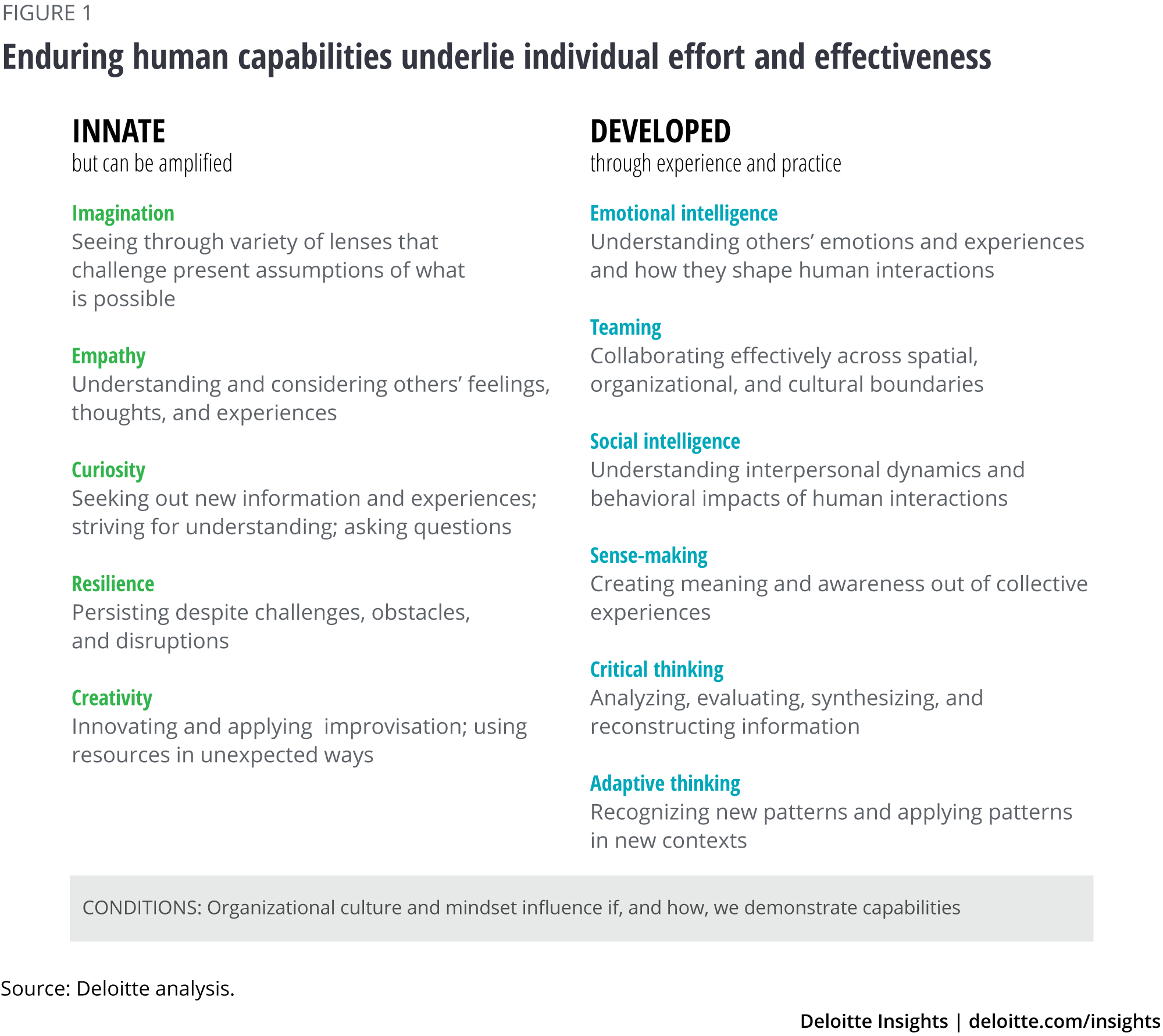

We define enduring human capabilities as observable human attributes that are demonstrated independent of context. These human capabilities can be thought of as universally applicable and timeless, and they are becoming increasingly important and valuable.6 Not only do these capabilities help us address evolving needs, but they can also help individuals keep adapting the skills they have and be motivated to acquire new skills rapidly and through a variety of channels suited to the conditions and requirements of the opportunity. In this regard, humans with well-developed capabilities are the most highly reconfigurable of assets.

Humans have an important role to play in creating value if we focus on cultivating and using enduring human capabilities. For instance, humans are better than machines at connecting with and understanding the variable needs of other humans; at recognizing and adapting to highly specific and changing contexts; and at developing creative and imaginative new approaches. And these activities, unlike skills, are broadly applicable across fragmented needs and markets, as well as over time.

Few large organizations, other than perhaps those in explicitly creative industries, take capabilities seriously enough to consider them a key input and strategic advantage. Historically, they didn’t have to: They could rely on standardized efficiency and mass production, with their less-demanding skills needs, to succeed through scale. But now that success demands a greater number of faster-evolving skills, organizations will need to adapt. Across industries, organizations that embrace, nurture, and cultivate enduring human capabilities through their workforce will likely have a strategic advantage, because their people will have the mindset and disposition toward rapid learning that is required to thrive in an environment of constant disruption.

What capabilities are we talking about?

Innate capabilities are those that we are all born with—they are part of our humanness. These innate capabilities might include curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and resilience. However, just because we are born with them, it doesn’t mean these capabilities are fixed; they can be cultivated through use and deliberate or inadvertent experiences and exposure. They can be amplified in an environment with the right conditions. In an environment where the work doesn’t require or reward manifesting these capabilities, or even punishes it, they may be underdeveloped and go dormant.

Developed capabilities are those that must be established and refined over time. These include adaptive and critical thinking, teaming, social intelligence, and emotional intelligence. While some people are less able to easily or effectively use these capabilities, most people have the potential to improve them through experience and practice. Note that this is not an exhaustive list of possible important human capabilities, but it provides a foundation and direction toward the types of capabilities that seem most relevant to the workforce broadly. As we move into that future, additional capabilities may rise in importance and the way they are understood may evolve.

These distinctions aren’t etched in stone so much as drawn in sand—there are interdependencies among capabilities7 and between capabilities and skills. Developed and innate capabilities depend on and reinforce each other. For example, imagination helps loosen the walls of our mental models to make space for creativity, both of which manifest to fuel adaptive thinking. Critical thinking helps to constrain and direct the products of imagination and curiosity.

Capabilities are key for creating the new value the market demands

Capabilities help businesses create value in more ways than one. The first way is self-evident: While traditional skills development may be too slow and expensive to address the needs of a fragmented marketplace, cultivating capabilities that encourage people to explore and master new skills on their own, or with minimal employer-provided training, can allow an organization to reskill its workforce more quickly and with greater alignment to marketplace needs. In the near term, for instance, an organization may need someone who can operate a certain piece of machinery or use the company’s spreadsheet software to generate a budget. But these skills are readily learned one on one, in the moment and in the environment where a worker needs to use them. Between YouTube, Degreed, Coursera, Udacity, Udemy, and many other online and in-person options for learning, individuals can pick up specific skills as needed—provided they are prepared and motivated to identify what new skill or resource might be needed, learn it, and work through how best to apply it.

Capabilities are what equip individuals to do these things. Capabilities such as empathy, which allows people to read the interpersonal context, and creativity, which helps people come up with novel ideas, can drive individuals to recognize where they or others may need help and help individuals identify what additional skill or resource might be needed to address the situation. Capabilities such as creativity and resilience motivate them to persist when learning skills and get better at adapting and reapplying when in the next context. And capabilities such as imagination and adaptive thinking can help them find multiple options for learning a skill in a way that fits the current need.

This is why companies and individuals should move past a mindset of dependency on specific skills. Both will benefit from the greater versatility and ongoing learning that arise from cultivating capabilities. Over time, capabilities will help individuals continuously develop the skills to remain relevant, ensuring companies can continue to develop the workforce they need.

The second way capabilities can benefit a business can be even more valuable. Skills alone won’t allow a business to identify and address new value-creation opportunities.8 For that, companies need attributes such as creativity, imagination, critical thinking, emotional intelligence—in fact, the whole battery of enduring human capabilities. This has always been the case, of course, but it’s even more true today, when empowered customers, heightened competitive pressures, and the accelerating pace of technology are driving the need to have more and better new ideas more often than ever before.

With well-honed capabilities, people, aided by technology, can identify and address unseen opportunities in ways that meet rapidly evolving and emerging needs and create the types of value that customers desire. Capabilities support this type of work by enabling deep connections with customers and coworkers (such as through emotional intelligence and empathy); by enhancing one’s awareness of differences and similarities between contexts (through capabilities such as creativity and imagination); and by enabling people to develop an unending array of approaches to address complex challenges (drawing upon resilience to persist in the face of potential failures).

You can see these innate capabilities on display in a playground or an early elementary classroom. Children naturally ask questions, testing their understanding, playing with boundaries and rules rather than taking them as static—wondering what might happen if … Children haven’t been taught to be curious or imaginative—they just are. At the same time, they don’t all display the same level of each capability or manifest them in the same way. Personality comes into play; so does the drive and motivation for accessing, developing, and expressing capabilities.

But you don’t have to go to the playground, or an animation studio or ad agency, to find capabilities. Even in a scalable-efficiency world oriented around standardized, repeatable processes, many workers already exercise both innate and developed capabilities to adapt to what are called “exceptions.” They use creativity, imagination, social intelligence, and adaptive thinking to develop workarounds when new needs or unexpected conditions create situations that fall outside established systems and policies. They use curiosity and empathy to inquire into these exceptional situations and identify what value will be acceptable.

Unfortunately, at many organizations accustomed to pursuing standardized efficiency, most manifestations of human capabilities tend to stay under the radar—or, at best, simply tolerated rather than encouraged. The frequent goal, stated or not, is to use capabilities to deal with the disturbance, smooth out the variances, and get back to business as usual—the sooner, the better. Commonly used metrics, too, reinforce this stance. “Improvement” or “success” is defined as churning out as many predictable results in as little time, and consuming as few resources, as possible; anything else is termed a defect, fault, or waste.

For the reasons we’ve discussed, this mindset of allowing just enough creativity on the margins to fix “exceptions” is no longer a good fit for marketplace demands. It won’t identify the types of new value-creation opportunities companies need to succeed in a market of powerful customers with specific, ever-changing expectations. To continuously offer differentiating value, companies need to create environments that not only accept the use of capabilities to fix “exceptions” but that actually expect and encourage workers to exercise their capabilities in all of their work—recognizing that most value-creating work will fall outside the standardized norm.9 In fact, when emerging needs conflict with standard processes, that's often an opportunity to create new value that will deepen the relationship with the customer.

The value of capabilities extends to all of a company’s activities. Returning to the example of Toyota, the company’s production system illustrates how a business can encourage capabilities to manifest on the factory floor. It begins with the clear leadership expectation that frontline workers will focus on problem-solving. Then, when an issue occurs, workers exercise curiosity to ask questions that can help identify the problem and the conditions surrounding it. They use social and emotional intelligence10 to pull others from the line and beyond to come together effectively around the problem. They use imagination to play with the boundaries of the problem and probe the constraints of the systems and tools; they creatively deploy tools using a new approach or technique adapted to the current needs.

Importantly, Toyota’s leadership demonstrates commitment to the notion that frontline workers—whomever is “on the ground” where an issue arises—have the best understanding of the context in which the problem occurs, and are thus the most appropriate people to solve it. The underlying assumption is that workers can be trusted, and have the motivation and capabilities, to develop and try out solutions. The return to hands-on crafting described at the beginning of this article further demonstrates how deeply Toyota’s leaders appreciate that workers must cultivate capabilities associated with reading and adapting to context to identify and address problems.11

Get started

If capabilities are so important, how do we cultivate them? The answer is both simple and complex.

The enduring human capabilities we are talking about aren’t rare, hard to find, or restricted to certain groups. They are present in all of us, and they can be used by everyone. And one of the most exciting aspects of capabilities is that, not only do they hold a key to long-term and ongoing relevance, but they can be cultivated without a huge capital investment. Think of the capabilities as a muscle. Everyone has them, though they may be atrophied through lack of use—and, as with muscles, capabilities strengthen rapidly once one starts to use them.

An organization’s mindset, management practices, systems, and work environment can be crafted to encourage and amplify, rather than discourage and dampen, people’s use and expression of their capabilities. Too often, institutions inadvertently teach people not to be curious or imaginative or to embrace other capabilities: Stop interrupting with questions, you didn’t follow the rules. Some organizations’ management practices and policies tend to deliberately and explicitly squash the expression of capabilities: We have a deadline! Why are you wasting time, what don’t you understand, we already have an answer, this worked last time, that won’t work. At other organizations, the discouragements are more subtle, such as promotion of those who never admit uncertainty or failure, or even a strong compliance culture, a tendency toward filling the calendar with meetings, or a culture of consensus. Whether overt or implicit, these forces working against capability development will need to be identified and countered, and new, more productive practices formulated and adopted.

Getting started doesn’t have to mean creating a big training program. The first steps can be as small and as varied as a leader setting a metric around opportunity identification; a manager giving people time to dig into exceptions and setting the expectation that they will do it visibly and deliberately; or a team leader looking for and mitigating the most obvious obstacles to people exercising their capabilities.12 But to bear fruit, efforts like these must be backed by leadership commitment to adopt a new, different approach to the talent challenge. Instead of looking to continuous skilling and reskilling of their workers as the answer to keeping up with marketplace demands, the business should aim to bridge its skills gaps by prioritizing creating an environment that develops and cultivates people’s core capabilities. This approach takes courage, as it requires leaders to have faith that enduring human capabilities do indeed drive skills and business value. We invite you to take the leap.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Future of Work

-

Future of work Collection

-

If these walls could talk Article5 years ago

-

The digital workforce experience Article5 years ago

-

Measuring human relationships and experiences Article5 years ago

-

How to redesign government work for the future Article5 years ago

-

The future of work isn’t scary, but it is misunderstood Collection5 years ago