How to redesign government work for the future A step-by-step guide to optimizing human-machine collaboration in the public sector

25 minute read

05 August 2019

William D. Eggers United States

William D. Eggers United States Amrita Datar Canada

Amrita Datar Canada David Parent United States

David Parent United States Jenn Gustetic United States

Jenn Gustetic United States

As more and more business leaders redesign jobs around AI, robotics, and new business models, here are steps public sector leaders can take now to transform their workplaces and maximize human and machine capabilities.

Most of today’s jobs will not be here tomorrow. The World Economic Forum predicts that 65 percent of children entering primary school today will ultimately end up working in completely new job types that don’t exist today.1 This represents an opportunity for government organizations and employees to intentionally redesign work and jobs to not only accommodate the role of technology and machines, but also to design for recent needs and activities, including those resulting from broader economic, workforce, and societal shifts. For example, a government HR manager who now only hires full-time employees may need to start tapping into a pool of crowd workers or gig workers for certain types of work. A procurement department may now need talent with blockchain expertise to manage secure supply chains. Or given the increased use of algorithms in government systems, agencies now need to prevent algorithmic bias from creeping into public programs.

Learn more

Explore the Government & public services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Some organizations have already started to take the first steps around redesigning work. In a recent Deloitte survey of more than 11,000 business leaders, 61 percent of respondents said they were actively redesigning jobs around artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and new business models.2

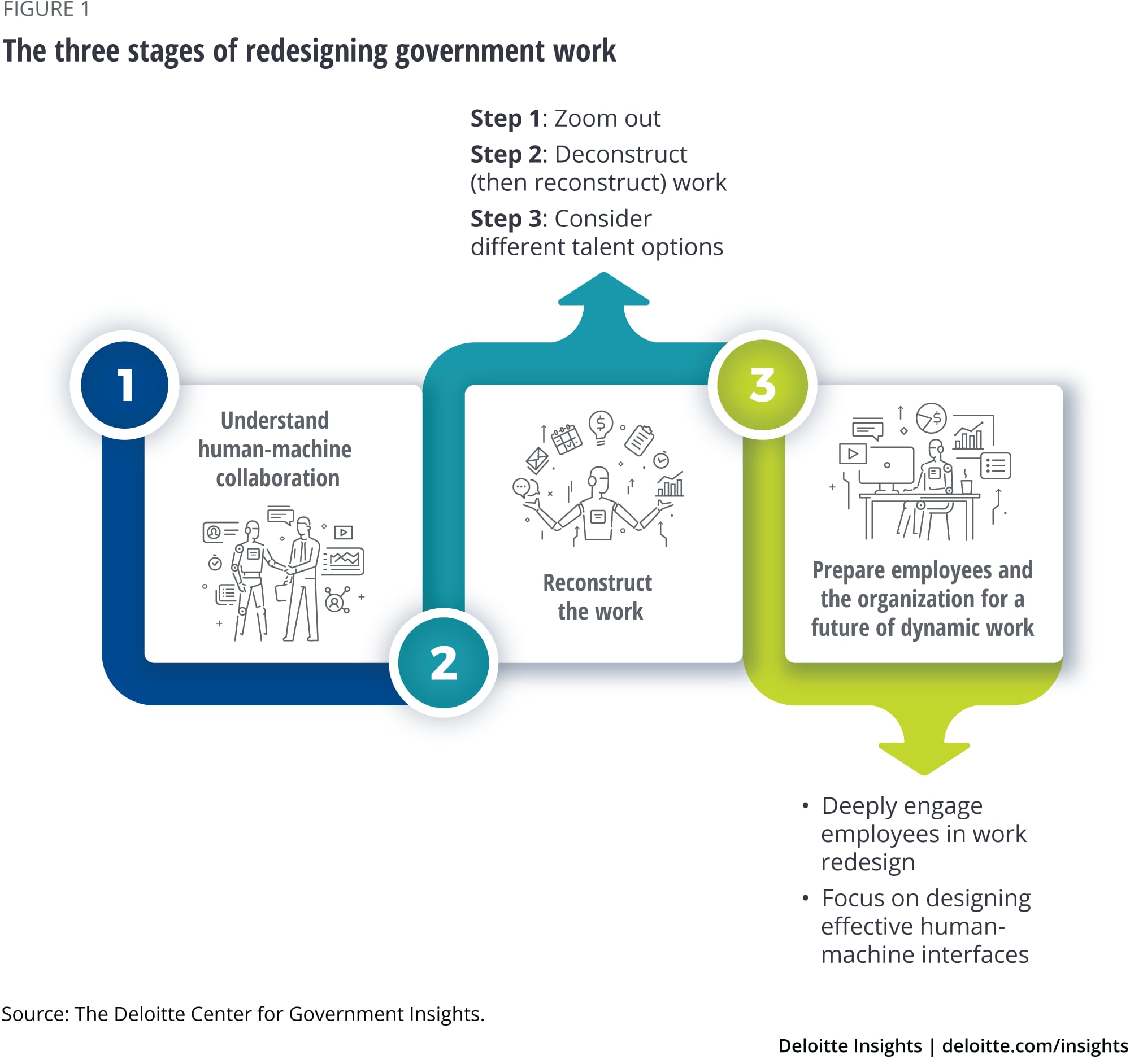

In this paper, the next in our series on the future of work in government, we’ll explore what redesigning work might look like for government organizations. We will also lay out some key design considerations and principles for organizations beginning to think about applying this process (see figure 1).

Let’s start by looking at one of the most significant factors transforming work: human-machine pairing, or how humans work with technology and machines.

Understanding human-machine collaboration

Across industries, the prevalence of automation, as well as machines working alongside humans, is increasing. Government is no exception. In fact, according to the US Office of Personnel Management, almost one-half of government agencies’ workloads could be automated and close to two-thirds of federal employees could see their workloads reduced by as much as 30 percent.3 That makes it an imperative to focus not only on how humans and machines can best collaborate at work, but also how that collaboration can enable better work processes and create more value.

Although there are many ways in which humans and machines can work together, we typically identify the human as the supervisor or the primary worker. This view can be limiting. Machines work for us, with us, and sometimes they even help guide us. Just think about rideshare drivers—acting on instructions from an algorithm that chooses their passengers, the fare they charge, and the route they take. To harness the real potential of the human-machine partnership in the workplace, we should widen the aperture and consider the full spectrum of possibilities (see figure 2).

Shepherd: A human manages a group of machines, amplifying their productivity

Here are some ways in which humans can serve as shepherds to machines in the workplace:

- A human manages a fleet of autonomous buses. The buses behave as a swarm, attempting to maintain separation between vehicles and keep themselves on schedule, while the human monitors the buses to identify problems or issues they need to step in and resolve.

- A nurse manager oversees a group of hospital robots. Several hospitals have piloted the use of robots for tasks such as transporting medication, supplies, and test samples within the hospital. A human can supervise and manage the robots, changing or reassigning tasks and schedules as required.

Extend: A machine augments human work

Humans and computers combine their strengths to achieve faster and better results, often doing what humans simply couldn’t do before, for example:

- A department of human services uses cognitive technology to help predict which child welfare cases are likely to lead to child fatalities. The department uses machine learning to predict which cases carry the highest risk. Once high-risk cases get flagged, they are carefully reviewed and the results are shared with frontline staff, who then choose remedies designed to lower risk and improve outcomes. This process helps field staff target investigations based on risk rather than on random samplings.4

- Cognitive technologies can be used to scan through vast amounts of medical data to help doctors make faster and more accurate diagnoses. For example, Google’s Deepmind algorithm analyzes 3D retinal scans to detect signs of eye disease. And IBM’s Watson for Oncology is designed to help physicians make more fully informed decisions by recommending individualized cancer treatments, citing evidence and a confidence score for each recommendation.5

Guide: A machine prompts a human to help them adopt knowledge

Machines help humans learn new knowledge and skills, or adopt desirable attitudes and behaviors. Here are two scenarios:

- Adaptive learning. The US Air Force, working with a startup called Senseye, is redesigning its pilot training program, using VR simulation. The system tracks factors such as cognitive load levels, stress levels, and a pilot’s ability to plan ahead and strategize. As Senseye’s Founder, David Zakariaie, explains, “The AI will build a custom syllabus for each pilot based on what’s going on in their mind.”6

- Digital research assistant. A researcher can set up a custom assistant that not only knows what current research a person is doing (based on their writing and speaking on their technology) but can also crawl the web for old and new research relevant to the topic that the researcher might not be aware of. This allows researchers to conduct literature reviews and stay up to date on the most recent advances much more quickly, accelerating their learning.

Collaborate: A problem is identified, defined, and solved by human-machine collaboration

Humans and machines collaborate to create solutions superior to those that either could create on their own, for example:

- An AI-enabled chatbot or interactive voice response (IVR) system could work together with a human services caseworker to provide services to a client in need. As the employee engages with the client on the phone, the AI system could transcribe the conversation, automatically flagging relevant information as it comes up. This would allow the human to focus on the conversation and contextual clues, while the AI would simultaneously suggest tactical solutions.

- A mobility manager who oversees a city’s transportation operating system. Most of the time, the system would operate autonomously, while the manager monitors the activity to make sure all is going well. But when problems arise, the manager would collaborate with the system to identify the problem and find an appropriate solution. Based on the situation and available information, the algorithm might recommend specific mitigating action, but it’s up to the mobility manager to accept that suggestion, or reject it and use a different tactic.7

Split up: Work is broken up and parts are automated

When a job is broken into steps or pieces, automating as many as possible, humans are left to do the rest and, when needed, supervise the automated work. Here are some current examples:

- Ride-sharing. The machine assigns a driver to a trip, monitors their progress, collects a rating at the end of the trip (which is factored into the worker performance calculation), and handles payment. The human steps in to drive the car (at least for now).

- The Georgia Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission processes about 40,000 pages of campaign finance disclosures per month, many of them handwritten. After evaluating other alternatives, the commission opted for a solution that combines handwriting recognition software with crowdsourced human review to keep pace with the workload while ensuring quality.8

- Chatbots. A number of government agencies around the world, from the Australian Tax Office to US Citizenship and Immigration Services, use chatbots to answer basic questions. This frees up time for employees to respond to more complicated inquiries.9

Relieve: Machines take over routine, manual tasks

This is when lower-value, manual, tedious work is automated, creating opportunities to reduce cost and redeploy staff time to more valuable activities. Examples include:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) uses robotic process automation (RPA) in its application intake process. When CDER automated a part of the drug application intake process, it slashed application processing time by 93 percent, eliminated 5,200 hours of manual labor, and saved US$500,000 annually.10

- San Diego County uses RPA to verify the eligibility of low-income applicants who claim benefits from government assistance programs. The software looks at the open forms on a caseworker’s screen, sifts through the verification fields, identifies relevant documents, and then pulls up those documents from another system, replacing a once-manual task with the stroke of a hot key. As a result, the county decreased the time it takes to approve a Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) application from 60 days to less than a week.11

Replace: Machines completely perform a task once done by humans

Once staffed by humans, here are examples of entire jobs that are being fully automated:

- Toll collection. Once performed manually by workers, collecting tolls has been automated in most states. In 2016, Massachusetts replaced 32 toll booth locations on the Massachusetts Turnpike with automated tolling technology.12

- Mail sorting. The US Postal Service uses handwriting recognition to sort mail by ZIP code; some machines can process 18,000 pieces of mail an hour.13

Bringing it together

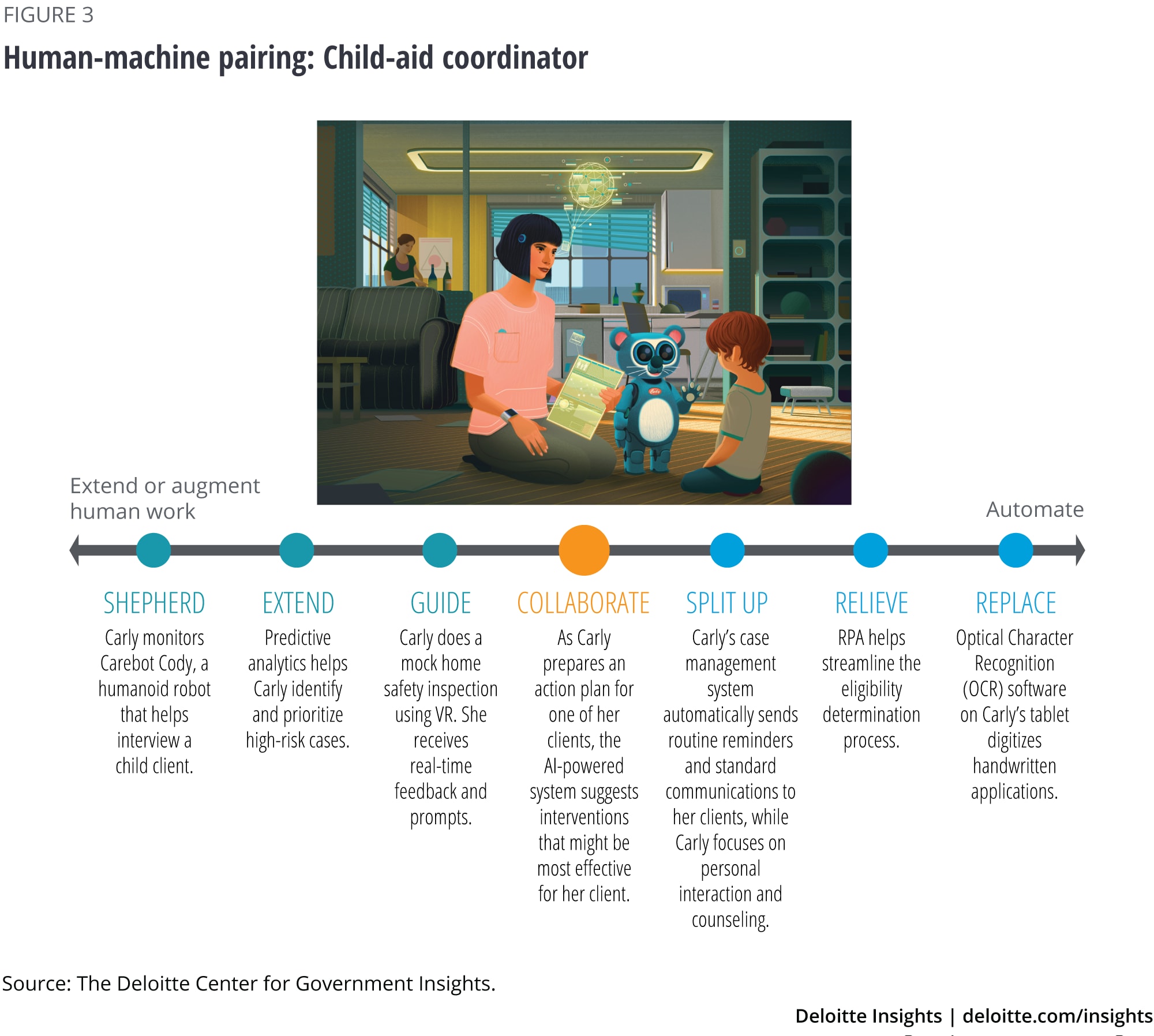

Humans and machines can work together across some, or even all, of these options within a single role. Consider the role of a child welfare worker of the future (see figure 3).

When humans and machines collaborate, and machines take over discrete tasks, this frees up the case worker’s time that had previously been spent on those tasks. So, how should she now spend that time? Seeing more clients? Spending more time with each client? Or doing something different, such as proactive problem-solving, learning a new skill, or mentoring others? And how might these changes affect her overall role? Is it essentially the same role, but improved, or does it transform into something new or different? What does this mean for her performance evaluation and future career paths? These are some of the issues that will need defining.

Redesigning the work

Work redesign is fundamentally about making sure that government agencies—their work, workforces, and workplaces—keep pace with shifting opportunities and needs and are prepared for the future of work. But architecting work and jobs can feel overwhelming without a clear idea of where to start. We recommend these three steps:

Step one: Zoom out

What will the future look like for your organization?

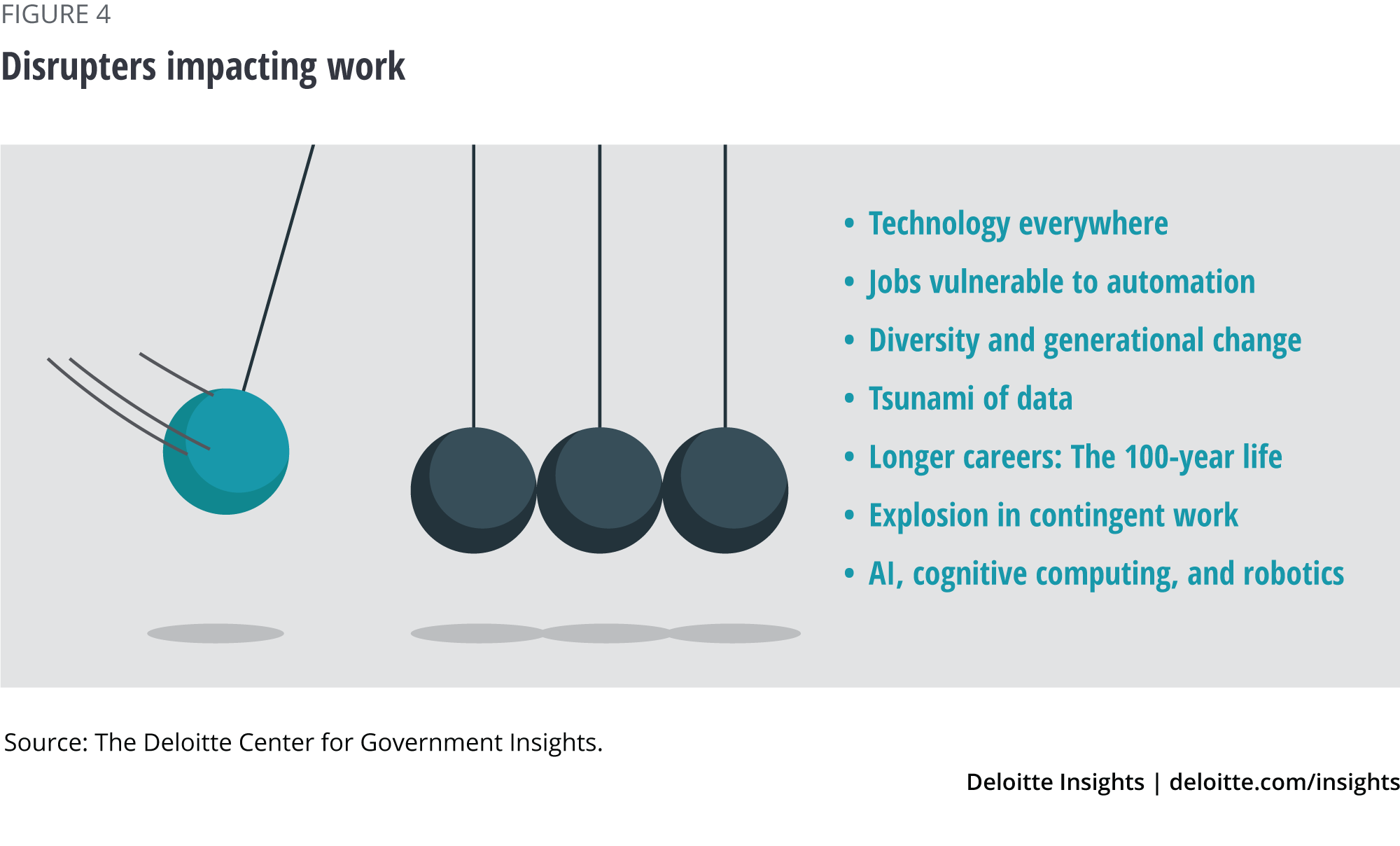

The first step is to think long term. Imagine what the future could look like, determining how this could impact your organization, and plotting out the course from here to there. There are a host of external forces—technological advancement, automation, changing customer demands and behaviors, or the rise of new talent and business models—that could impact how your government organization will work and deliver on its mission in the future. Mapping out at a macro level the effect the disrupters could have on the organization’s work can help inform its response plan and identify areas of opportunity and risk.

Imagine you’re looking out to 2030. People are living longer and staying in the workforce longer. The composition of the workforce has changed, too: Digital natives and younger generations would have joined the workforce, as well as more freelancers and contingent workers. Technology is omnipresent and AI, augmented reality, the Internet of Things (IoT), and robotics are integral parts of the modern workplace. Organizations may have new analytical capabilities, thanks to unprecedented volumes of data and computing power. Think about what all these factors and the changes around the corner could mean for your organization (figure 4). By zooming out, hopefully you will explore beyond what technology and other disrupters can allow you to improve on what you’re already doing. This activity can help you envision how these changes could enable you to unlock entirely new outcomes and rethink your organization’s strategy, mission, and/or business outcomes.

Step two: Deconstruct (then reconstruct) work

What work should be done differently?

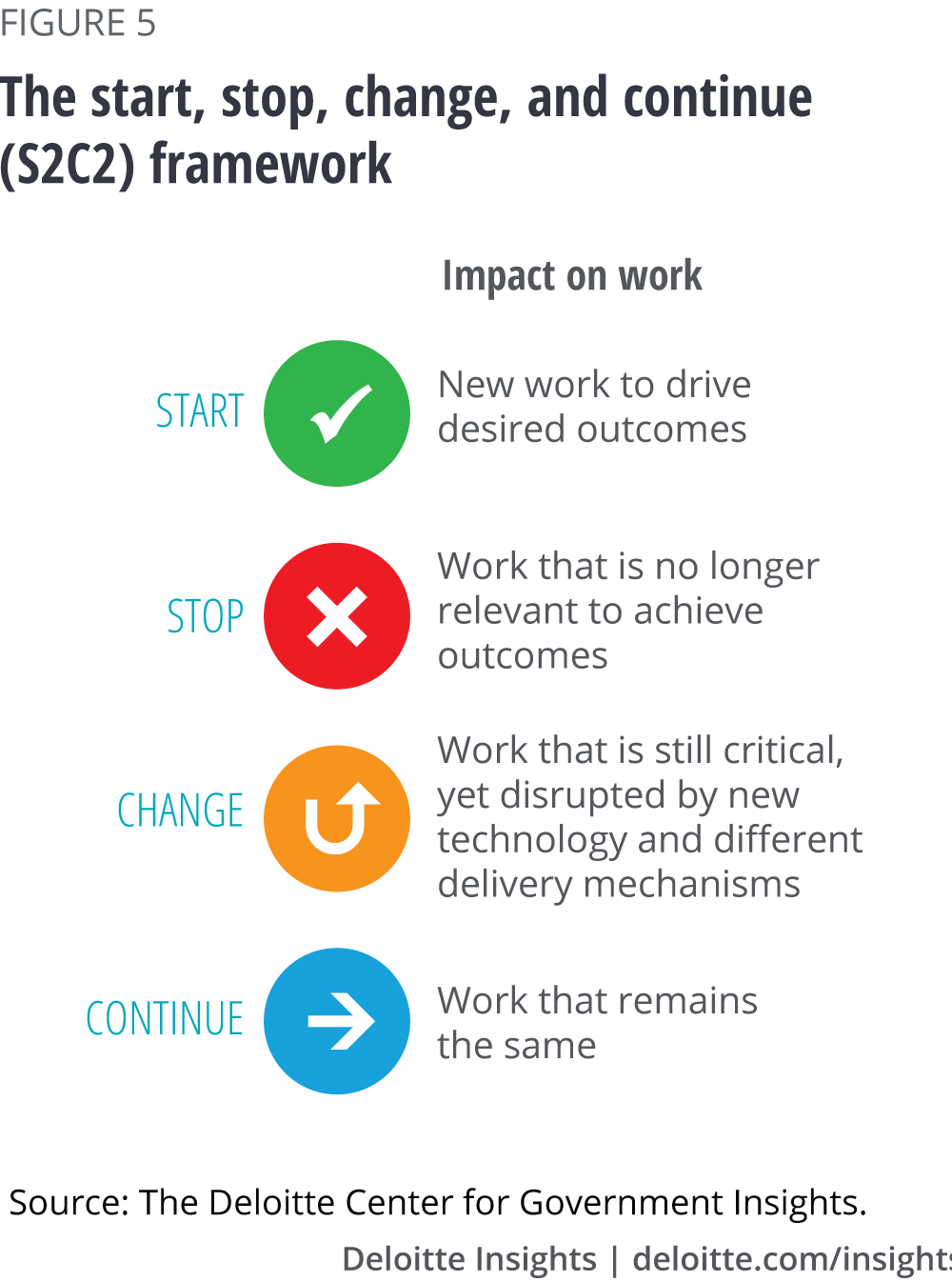

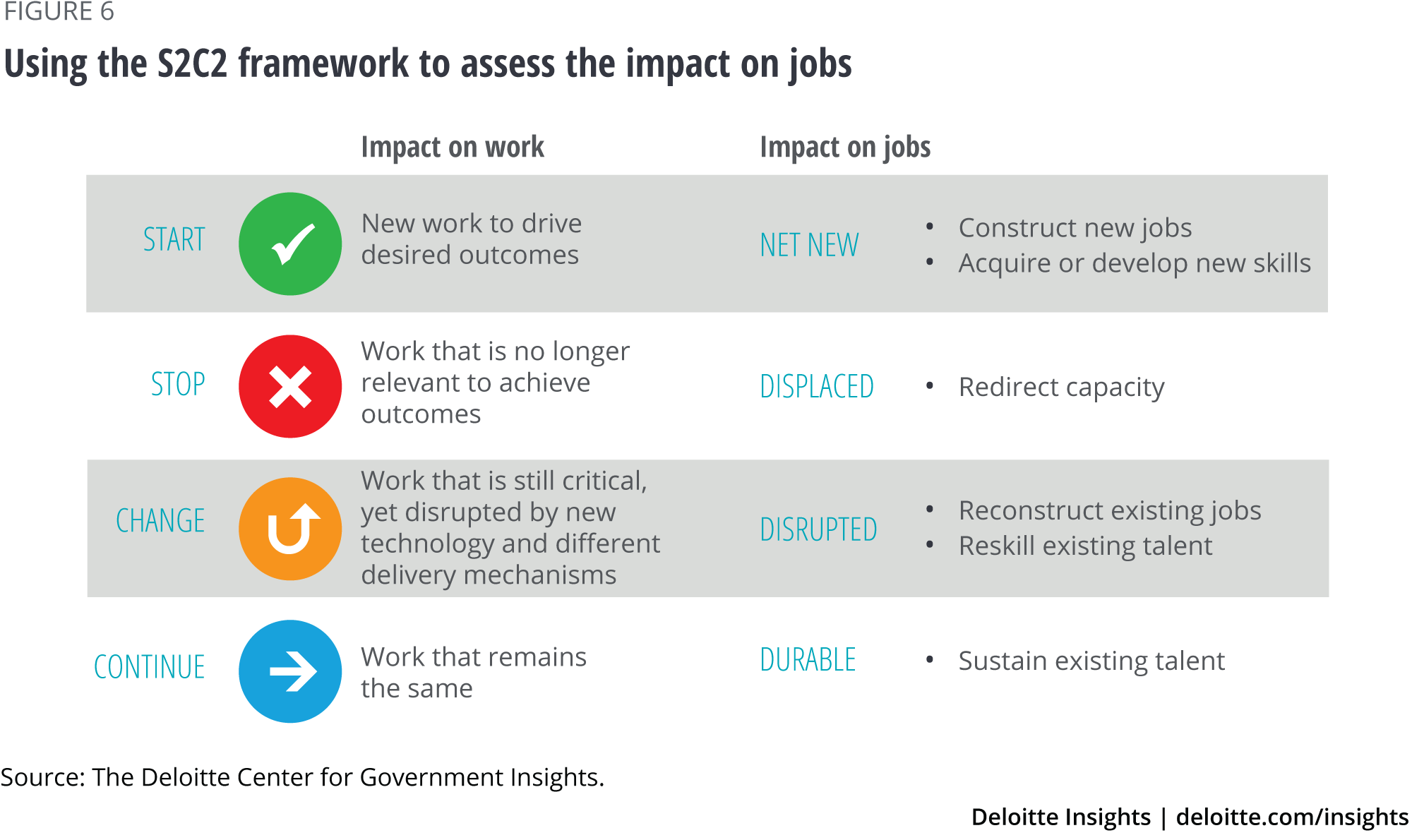

Given the vision you’ve imagined for your organization and the role disrupters can play, think about the current state of work across the organization. Ask, “What might we do differently across different jobs and work units to achieve greater impact and desired outcomes in the future?” The process of deconstructing (and then reconstructing) work, and then defining the new roles that can support the new disciplines, can be broken down into four focused pieces with a simple framework (figure 5): Start, stop, change, and continue (S2C2).

Some work will be catalyzed by technology and other disrupters and start anew. Meanwhile, some dull, dirty, or dangerous work may be automated or stopped entirely. Some work will be still critical to mission and business outcomes but will be changed by the application of technology. And, lastly, some work will continue relatively unchanged.

For example, a government agency might start hiring gig workers for certain skills such as data science. A transportation department might stop installing and maintaining traffic lights when autonomous vehicles become the norm. Given the dangerous nature of their work, firefighters might change how they extinguish fires and use drones and robots instead to assist them. Social workers will continue to visit their clients in their homes and build a personal connection. In some cases, these changes could also result in humans working alongside machines—for example, the firefighter shepherding a fleet of drones to fight a fire—so an understanding of how humans and machines can collaborate (explained earlier) is helpful.

The S2C2 lens can be applied to different levels of an organization—to a single role, across stages of a program, or at a high level within an organization’s department. Agency leaders can use this information to gauge the downstream impacts on the workforce and jobs. Starting new activities might require leaders to create new roles or jobs while changing and stopping certain activities might require reskilling and redirecting talent (see figure 6).

In the short to medium term, the changes to the work might not be very dramatic and may result in just a few new activities and skills needed. A new role may be added to existing jobs; for example, in a department that implements process automation, a group of employees now must interact with and manage bots as part of their daily responsibilities. They now have the role of “bot co-worker” added to their job description, but the rest of their job might not change all that much. Over time, this role might get added to many jobs and impact the entire workforce (see figure 7) and in the longer term, the organization may do enough automation that they need to reskill or hire full-time bot managers, which would be a new job.

In the future, the “matching” of evolving skills to evolving work (roles) within the context of a redesigned job should be very intentional. This can help ensure that you’re building a job that is a logical, holistic combination for a single person to have, rather than a somewhat haphazard mix as it often is today.

Think of it like this: What if by 2030, your current role no longer existed? How would the work get done? How would you rethink doing the work?

Step three: Consider different talent options

Who should do the work?

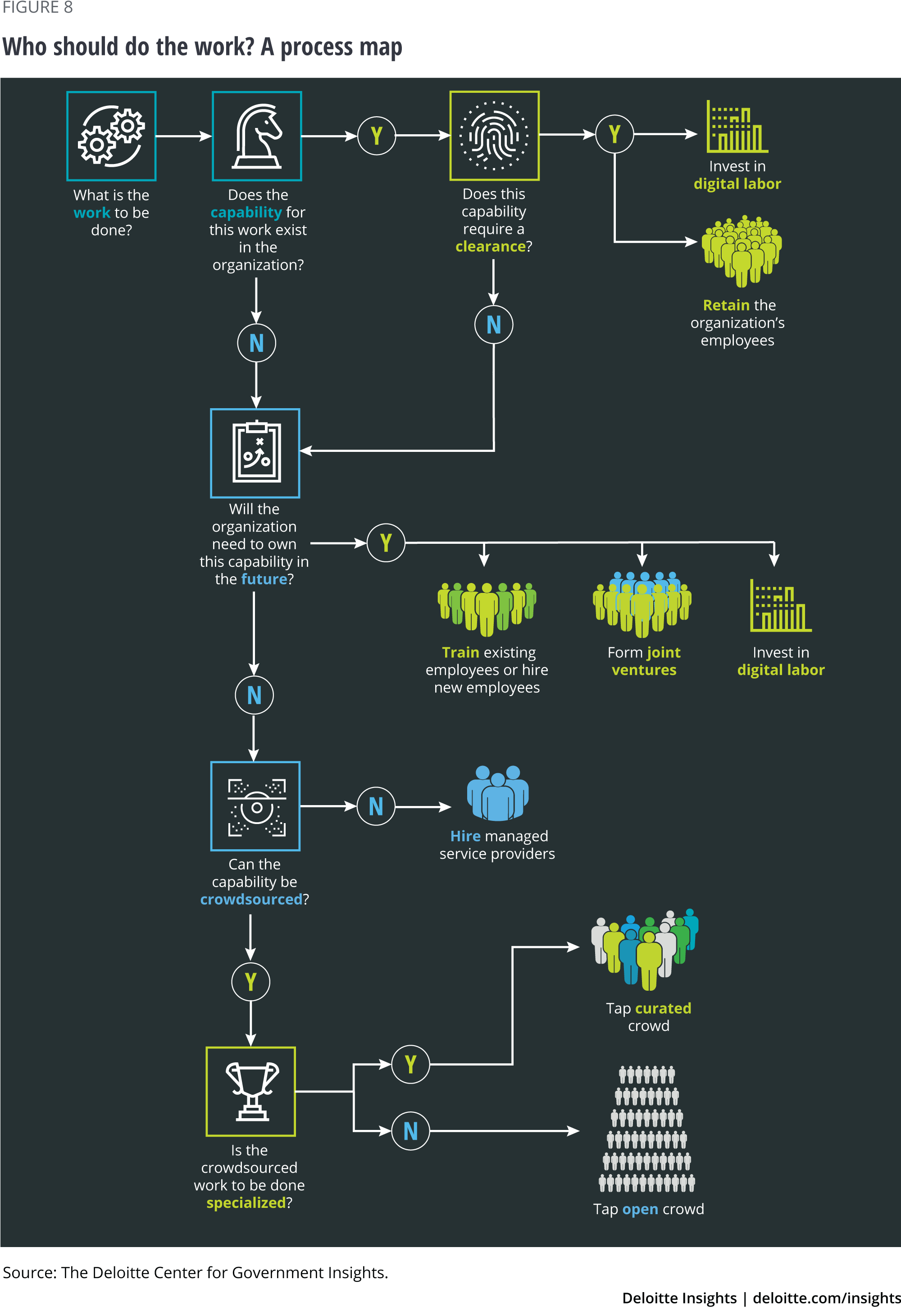

While reconstructing work, asking the question, “Who should do the work?” can help organizations explore new talent options—crowd workers, gig workers, or digital labor—that might not have been considered before. Depending on factors such as how specialized the task is, or whether the desired capability requires a security clearance, some talent options might be more suitable than others. (See figure 8 for a process map for determining who might be best suited to do the work.)

This approach also sheds light on organizational needs that might emerge because of changing work. For example, if it makes the most sense for permanent employees to handle the work, there may be new training and hiring requirements. To engage outside perspectives, leaders may want to develop or use a new crowdsourcing platform. Working with digital labor or AI may require leaders to select the most appropriate form of human-machine collaboration, to answer the previously asked question, “Should an AI technology augment the human worker or relieve them?” All these considerations feed into work redesign.

Work redesign in practice

We’ve now outlined several themes around reconstructing government work—exploring how work might change, who should do the work, and options for human-machine pairing. But what might that look like in practice? Two examples, one at the organizational level and one at the job level, can help leaders visualize how this could work.

Organizational level: State transportation department

Typically, a state transportation department is charged with planning, delivering, and maintaining transportation projects and infrastructure such as roads and bridges and enabling the safe and easy movement of people.

With demographic changes, mobility preferences, and shifting behaviors, transportation needs, too, will shift to meet demand. Ride-sharing, bike-sharing, scooters, electric vehicles, autonomous vehicles, and passenger drones are among a slew of emerging transport options. By 2040, it is predicted that more than 60 percent of passenger miles traveled in the United States will be in fully autonomous vehicles.14 Greater urbanization, environmental concerns, and shifting revenue streams could all have varying degrees of impact on a government department’s work.

Consider one of the biggest disruptions for transportation: the rise of connected vehicles that communicate with each other, accompanied by IoT and smart infrastructure. Over the next five years, the state transportation department might need to reconstruct its work (and jobs as a result) to keep pace with user needs and the changing transportation landscape. For example:

- It might need to start incorporating new data from sensors or partner agencies to drive planning decisions.

- It might need to stop building infrastructure without connected capabilities.

- It might change the types of platforms used to better communicate across agencies or change how it hires with a focus on new skill sets.

- It will continue to maintain existing roads and bridges.

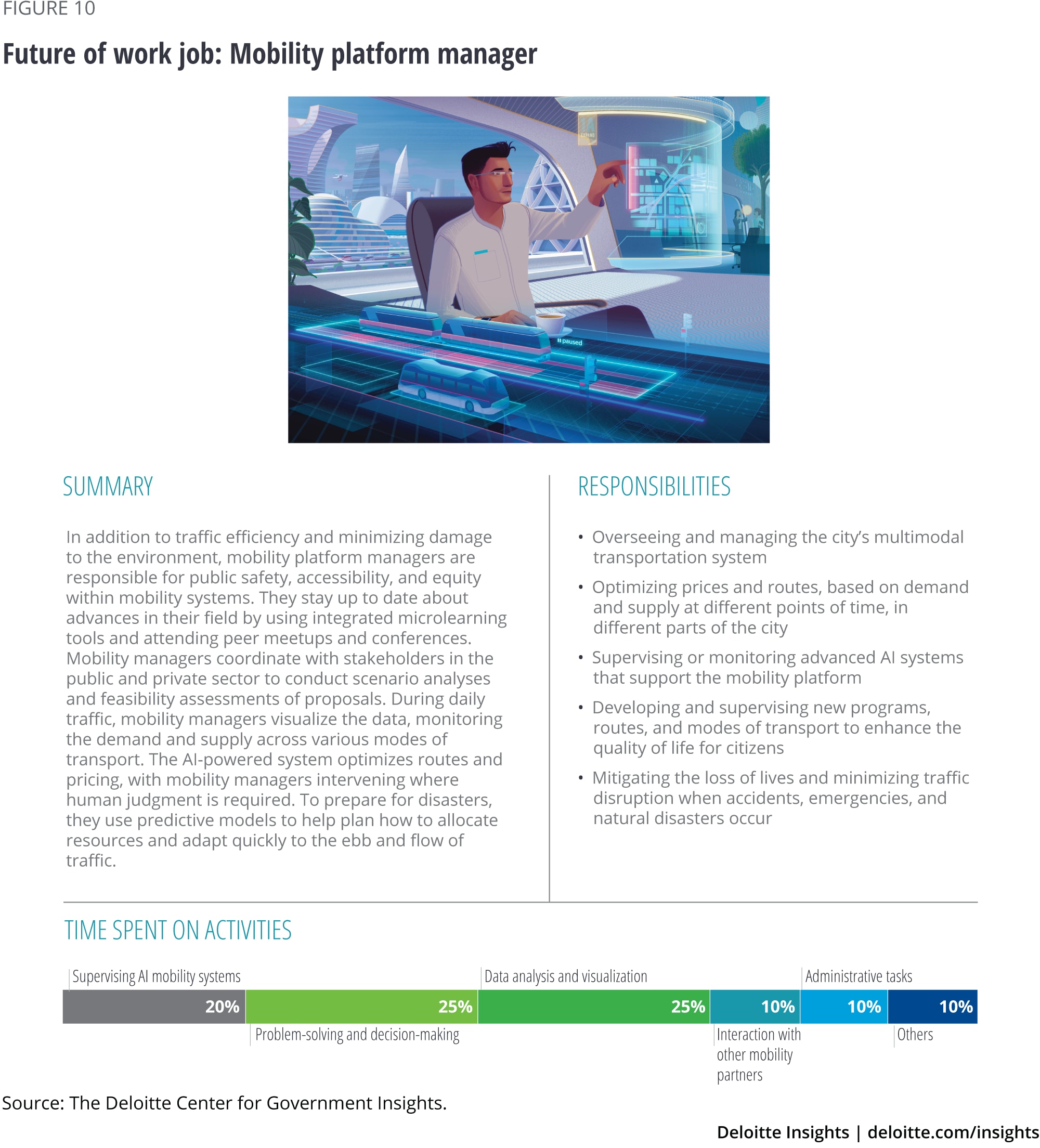

Some of these changes to work would have downstream effects on the workforce (see figure 9) in terms of new skill sets as well as career paths and jobs that might be created. These future jobs can be envisioned and expanded (see figure 10).

Job level: Law enforcement investigations

Historically, law enforcement investigations were driven by the information an agency had access to. We’ve all seen the detective from TV and films transfixed on an evidence board—a collage of information, photographs, newspaper clippings, notes, and other scattered nuggets—piecing together clues to build a picture of the crime.

Today investigators increasingly go to their computer screens to find answers. But they often encounter a massive, seemingly impenetrable wall of data. For example, in one year alone, a single FBI investigation collected six petabytes of data—the equivalent of more than 120 million filing cabinets filled with paper.15

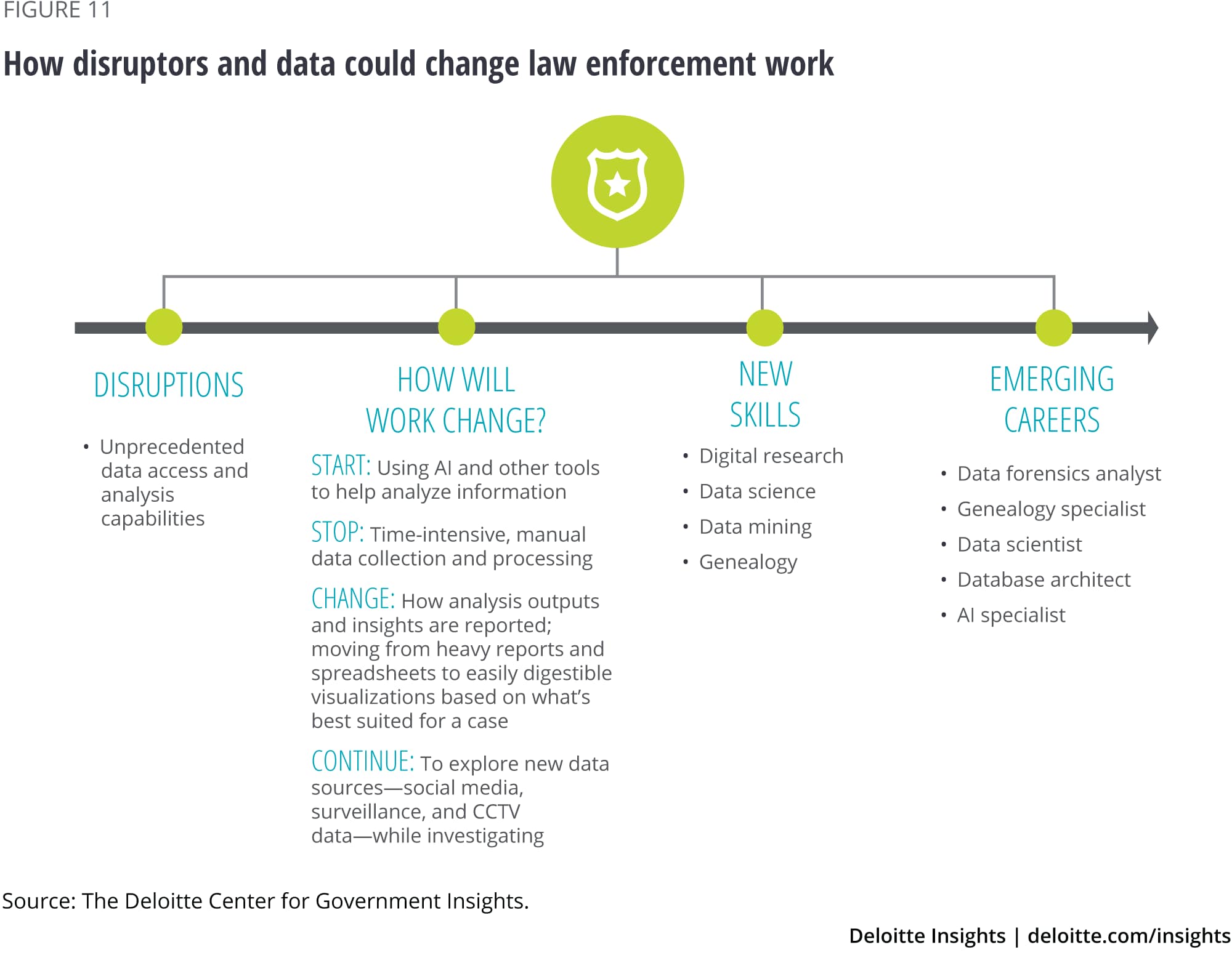

In the future, investigators will rely on new data tools to more rapidly find data, allowing them to spend most of their time analyzing it. AI, open source data management tools, predictive analytics solutions, and social media mining capabilities are helping many investigators make sense out of mountains of data. New tools can help connect information in new ways and identify where key information is lacking, new sources can provide access to reams of data, and new partnerships can help make the optimize use of the data.

So, what might investigators of the future do differently? They might:

- Start using AI and other analytic tools to help analyze large volumes of information.

- Stop engaging in time-intensive, manual data collection and processing and working in silos, where there is limited data-sharing and coordination across agencies.

- Change how analysis outputs and insights are reported, moving from heavy reports and spreadsheets to easily digestible visualizations based on what’s best suited for a case.

- Continue to explore new data sources—social media data, cell phone data, surveillance, CCTV data, and genealogy data—for investigations. For example, investigators have started to treat opioid overdoses as crime scenes rather than accident sites and will now look through an overdose victim’s phone. Cross-referencing the contact lists from different overdoses, they can often identify dealers.16

These changes would also have an impact on the overall law enforcement workforce (see figure 11).

Law enforcement agency leaders can plan for hiring, workforce training, and reskilling activities by thinking about what skills and capabilities might be needed to support law enforcement in the future. Investing in AI and technology solutions can help automate pieces of data processing and collection, while hiring and training personnel with specialized skill sets can free up investigators to focus on their core mission: solving crimes.

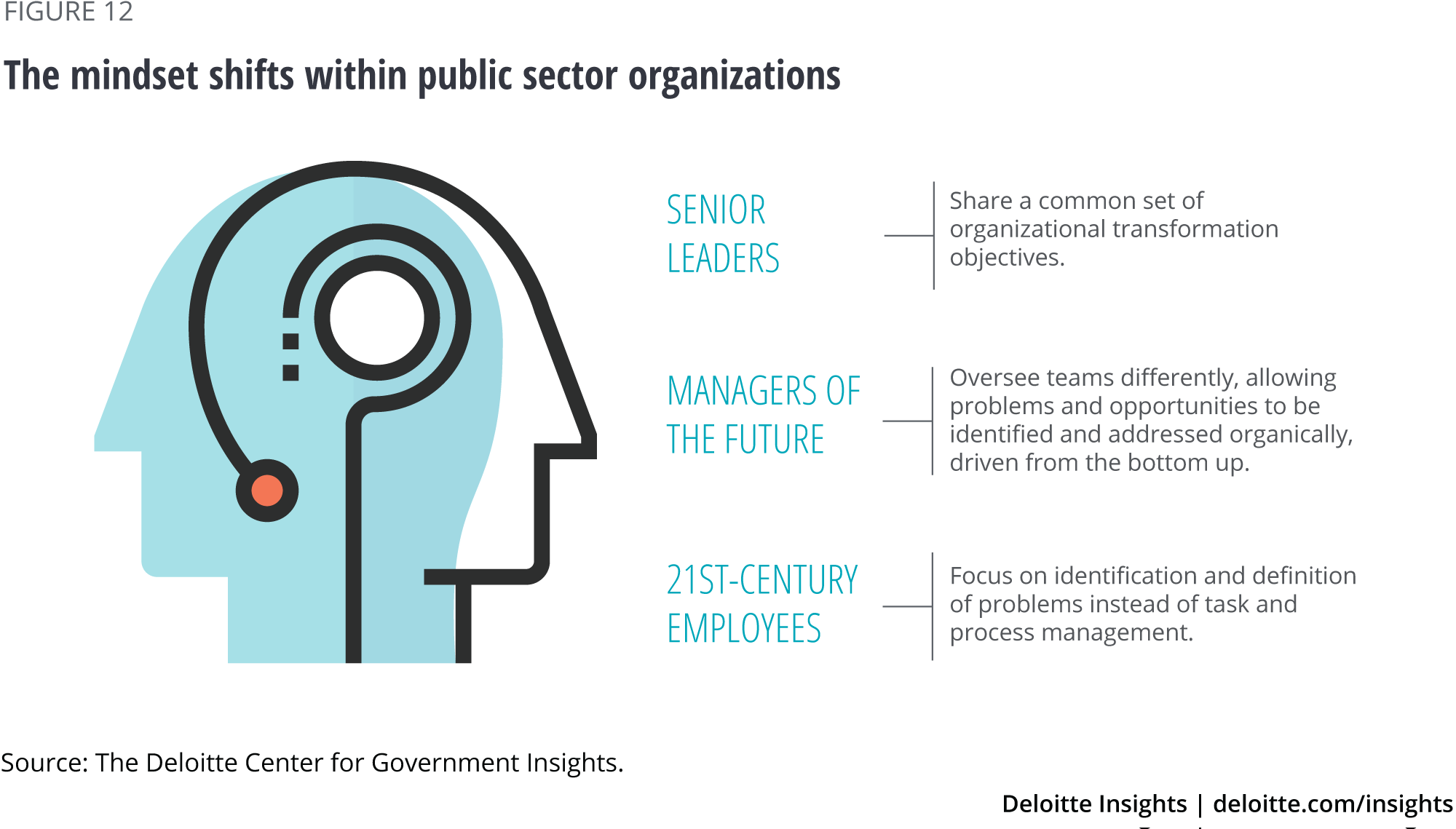

The new mindsets needed for a future of dynamic work

Reconstructing work as described in this report will require public sector leaders to shift their mindsets when thinking about three organizational levels: (1) the individual employee; (2) supervisors and managers; and (3) senior management (see figure 12). Organizations need to transform human resources to focus on providing the greatest value humans can provide (creativity, empathy, problem-solving, etc.). Failing to do so could put them at greater risk of automating the human out of certain work completely, which would signify a major lost opportunity in not only efficiency gains, but also in better and more value creation as well.

The Future of Work employee mindset

The empowered employee of the future will create value by identifying salient problems from the front lines of their program or project, working in conjunction with a suite of technologies (see the sidebar, “Future child case worker”). This will require a mindset shift: from task execution and process management to lifelong learning and identifying, defining, and helping to solve problems. Employees of the future should:

- Adopt an entrepreneurial mindset that questions past assumptions and relentlessly pursues constant learning about citizens and program outcomes.

- Practice lifelong learning—not necessarily through traditional higher education classes or in-person training courses but via online courses or MOOCs, or by joining communities of practice, local boot camps, or micro-courses designed to be taken on-demand.

Employees must understand that change is coming and seek the new skills that will be required for them to succeed in a changed work world. And they should feel empowered to take on some of the responsibility for that learning themselves. Humans are still vastly better than machines at problem-solving, communicating and knowledge sharing, collaboration, leadership, creativity, empathy, and coping with ambiguity and uncertainty.17 Maintaining these advantages through consistent learning and skill development will be paramount.

Future child case worker: Protecting vulnerable children through customized problem-solving

Child case workers in some states currently spend less than 10 percent of their workdays actually interacting with children and families. Instead, they spend most of their time on administrative tasks that could be reduced with the application of technologies.18 Their current administrative burden impacts their ability to most effectively protect vulnerable children and coordinate services for those children. Child-aid coordinators of the future will have more time and tools to customize services for vulnerable children based on each child’s unique circumstances.19

The Future of Work management mindset

The effective manager of the future will oversee teams differently, allowing problems and opportunities to be identified and addressed in a much more organic way, driven from the bottom-up.

These managers will embrace a value creation mindset when determining how to best pair human and machine resources to accomplish their mission. Automation of existing tasks alone will not maximize the public value their teams are able to generate. Managers of the future should seek to harness uniquely human skills (creativity, empathy, problem-solving, etc.) in combination with automation and technology (see the sidebar, “Future mobility platform manager”) to create more value. To do this, managers will need to:

- Set the vision for and drive a collaborative, innovative team culture by listening to and engaging the workforce and customers

- Design teams of the future that include multiple sources of skills, capabilities, and workforces, a combination of human resources (full-time employees, contractors, external crowds, and public-private partnerships) and machine resources (AI, RPA, etc.)

- Prioritize problems through modified work processes that harness human-machine coordination

- Coach employees through the process of identifying and defining problems to ensure a broader context is considered in designing and implementing human-machine coordination workflows and solutions.

Future mobility platform manager: Overseeing humans and machines to create better policy solutions for mobility in cities

Mobility options—such as car-sharing and autonomous vehicles, in addition to public transportation and personal vehicles—are expanding, making mobility management more complicated. Further, since mobility solutions are owned by a combination of individuals, the public sector, and the private sector, data management and public-private collaboration are critical to solve systemwide problems. Mobility platform managers of the future will manage teams of people who will supervise advanced AI systems that support the mobility platform. These mobility managers will focus their time less on process oversight and more on coaching and policy development.20

The Future of Work leadership mindset

Senior leadership should also embrace a new mindset, one that demonstrates a more collaborative and less authoritative leadership style. This work style will apply horizontally in collaboration with other senior leaders as well as vertically in the way senior leaders interact with frontline employees. While authoritative leadership creates a task and process execution mindset among employees, the workplace and organizational transformations of the future will need leaders who grant more autonomy to employees so they can execute effectively.

Leaders will need to shift their mindsets in three critical ways:

- Create the platform to enable new ways of working. Current efforts to reinvent and modernize government work, including the application of new technology, can often feel like hand-to-hand combat. Employees are confronted with a seemingly endless set of rules and requirements that are often counterproductive.21 Moreover, most of the leadership attention is focused on the automation of work as it is done today, without re-thinking the outcomes outlined earlier. Work transformation, therefore, will require management and senior leaders to enable new ways of working, from completing tasks to bottom-up problem-solving. To do this, leaders will need to create the platform for re-envisioning work.

- Think horizontally, not just vertically. Creating this new platform will require horizontally aligned collaborative leadership. Organizations should focus on aligning incentives through shared performance objectives across senior leadership to help achieve these goals. Without common performance objectives, different management functions (CFO, CHCO, CIO, etc.) may clash with one another. In setting the stage for the mindset shift required to enable the future of work, agency leaders should develop a shared set of transformation objectives for their senior leaders; otherwise, institutional resistance and misaligned objectives may derail managers’ and employees’ efforts to adhere to the new way of working.

- Prioritize workforce engagement. Senior leaders should also relentlessly try to engage employees in helping design jobs of the future. Employees see problems on the front line and opportunities to create value that management and senior leadership often don’t see. By incorporating frontline intelligence to design jobs that leverage human ingenuity in a more substantial way and are augmented by technology, organizations will be able to provide more value than they can today.

The role of design thinking in work redesign

Work redesign involves the substantial use of design thinking or user-centered design, as well as a strong focus on mission. With design thinking, leaders build a deep understanding of users and customers to improve their experience. Then, they use that information to make decisions around how to redesign the work process to support the organization’s core mission.

Deeply engaging employees in the work redesign

Organizational leaders should consider how their employees think and act. If you want to alter someone’s job or workflow, make sure you understand the status quo and engage those doing the work in the process of redesign. A few ways to do this:

Engage employees early and often in reconstructing work

How employees are engaged in the process of re-envisioning their work is important. Rather than having a one-off exercise that results in clear before-and-after scenarios, it should be an ongoing, iterative process. To make the process work, leaders will need to make it clear to employees that their mission, along with how they accomplish it, is a living and mutable process that employees have a role in shaping.

At the organizational level, several government agencies have implemented internal crowdsourcing and ideation efforts to encourage employee engagement and problem-solving. For example, internal innovation and crowdsourcing platforms could be used to solve higher-level agencywide problems that the workforce is experiencing. While the actual problems that surface through these kinds of channels may not be as significant as those identified through intentional small group brainstorming sessions, the employee engagement that comes with a well-managed ideation platform can have great value as one of a suite of tools leaders can use to transform to the future of work.

Prototype and test new technologies with users

Typically, the rollout of new systems involves the development of a new work process where technology is built, introduced, and people are trained. Training often doesn’t go well because it wasn’t designed for the user. The result? It creates workforce morale issues and the whole initiative is stigmatized as another “managing change” effort foisted upon employees, as opposed to engaging the workforce in identifying the opportunities for the change.22

MIT professor Thomas Kochan emphasizes this point in an article on engaging the workforce in digital transformation. “Waiting until a new technology is being introduced to retrain the workforce is too late. Instead, firms that want to be proactive in digitizing operations need to educate and train workers on a continuous basis, so they have the analytical and social skills,” he writes.”23

Observation, testing, and conducting surveys can help reveal how a new technology will affect the workflows of the people implementing it. Understanding the cognitive habits at stake is crucial to removing subconscious obstacles. Further, when leaders know a machine capability is going to be built, they should deploy an agile, user-centered approach to developing the technology.24 User groups should be involved in surfacing needs, developing requirements and user stories, testing, and rollout. This starts from the beginning of the development process and should not be an afterthought.

Use storytelling as a bridge between leadership and employees

Human-centered design and storytelling can help demystify the process of redesigning work. When the future can seem scary and uncomfortable, “humanizing” the change can be an important element to increasing the workforce’s comfort level with what’s about to happen. To accomplish this, we developed a series of personas or profiles of government employees of the future.25 While each profile includes a job description, it also shows—through the eyes of the worker—what a typical day might entail. How have their jobs changed? What tools and resources do they have access to? What kinds of skills and career trajectories do they have? By imagining what the future of government jobs could look like, organizations can begin to address what needs to happen to make that vision a reality. In this way, instead of being something that just happens to the workforce, the evolution of work and jobs can be designed by and for the workforce.

Designing effective human-machine interfaces

As humans and machines working together becomes the norm in the workplace, organizations must design a dynamic that maximizes the potential of the relationship to create better work processes for everyone. To accomplish this, consider the following:

Let humans and machines play to their strengths

An employee who is bogged down by a long list of mundane tasks is likely not going to have the bandwidth to spot new opportunities for value creation. Minimize the number of routine tasks workers must perform, and you can increase the potential for problem-solving and value creation. Automation can relieve workers of routine work, but often they will have not had a clear view of how various tasks could be automated or the tools that are out there that are available to them. Employing a technology translator—a technologist who can help teams think through their concept of operations—can help teams identify opportunities to automate routine tasks to free up time to perform higher value activities.

Design agile solutions that aren’t limited to information technology

Many processes that benefit from a design thinking approach are actually omnichannel, meaning they offer citizens several options: calling a helpline, chatting with a bot online, chatting with a human online, emailing a question, and/or checking FAQs on a website. They include both technology elements and in-person and physical elements to improve the overall service experience. There tends to be a focus around IT software as the only relevant machine, but other physical machines (robotics, UAVs, etc.) will also become increasingly important to the future of work. Furthermore, in an era of evolving human-machine interactions, technologies should be deployed in a way that allows them to be adapted to emerging needs and be modified relatively quickly.

Achieve employee buy-in by leveraging behavioral science principles that put the human before the technology

The difference between full adoption and technological “tissue rejection” is not always a question of the technology or even basic piloting strategy. It’s often a matter of paying careful attention to human behavior, especially when program performance depends on how customers interact with a process or service. An organization’s technology and strategy are implemented and used by real people, who are subject to cognitive biases. To improve the odds of getting work redesign to stick, organizations can turn to the field of behavioral science. Basic behavioral nudges can encourage people to transform their workflows even when faced with uncomfortable change.26

Realizing the full potential of human-machine pairing

By reconstructing work, government organizations can not only capture efficiency gains through human-machine collaboration; more importantly, they can find new avenues to create value that may not have been possible before. We have discussed how to reconstruct government work—exploring how work might change, who should do the work, and different options for human-machine pairing—using examples from law enforcement investigations to state transportation planning.

These future work scenarios don’t simply feature the human as supervisor of the machine; instead, they consider the full spectrum of possibilities for human-machine pairing. They identify work that might be automated or stopped, work that could be catalyzed by technology and start anew, work that will continue relatively unchanged, and mission-critical work that will be changed by the application of technology. To harness the real potential of the human-machine partnership in the workplace, organizational leaders should widen the aperture and consider each of these possibilities.

Furthermore, to harness the enormous potential provided by the future of work, government leaders and organizations should seek to advance the change both vertically and horizontally. Vertically by proactively architecting work units or specific jobs (such as demonstrated for child case management) and horizontally by encouraging organizationwide practices for redesigning work, including encouraging mindset shifts and embracing design thinking.

As humans and intelligent machines working together becomes the norm in the workplace, organizations have an opportunity to maximize the potential of both. This effort, when realized, can fundamentally help create better work processes for everyone and more value to taxpayers.

Explore the future of work in government

-

Government & Public Services Collection

-

Government jobs of the future Collection

-

The future of work in government Article6 years ago

-

How government and business can team up to reskill workers Article6 years ago

-

Reinventing workforce development Article6 years ago

-

Zoom out/zoom in Article6 years ago