What is the future of work? Redefining work, workforces, and workplaces

8 minute read

01 April 2019

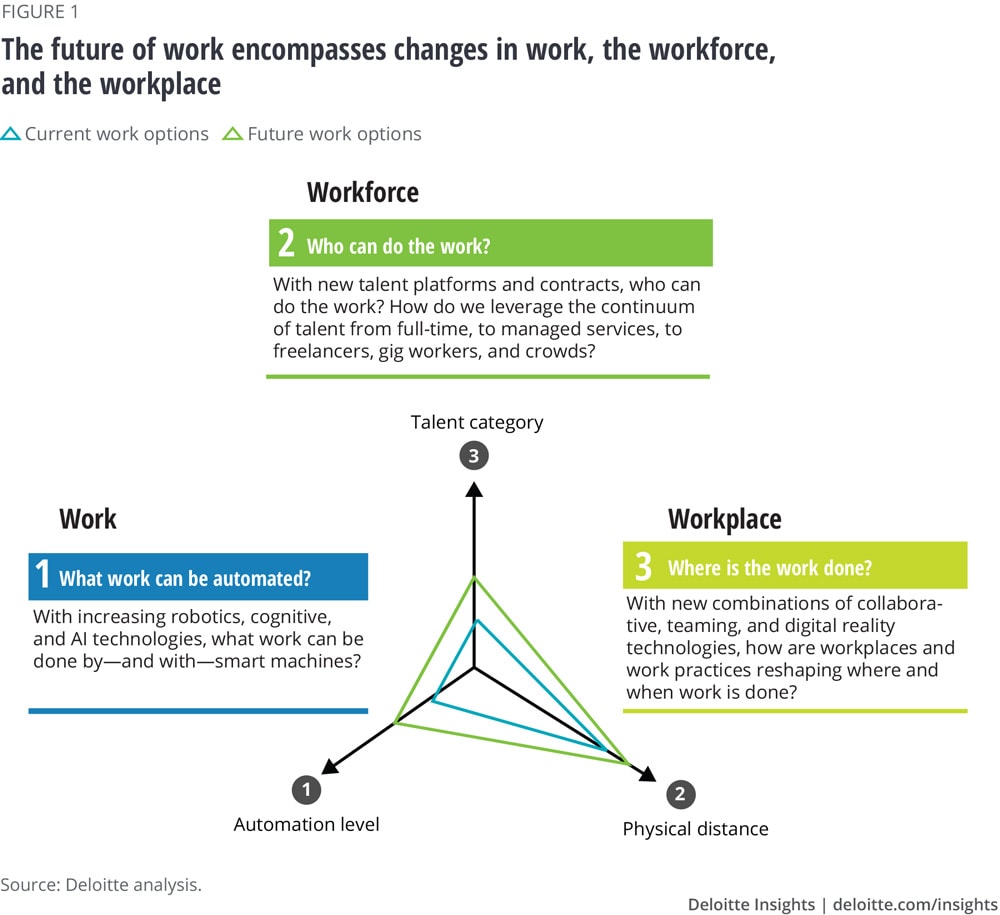

Forces of change are affecting three major dimensions of work: the work itself, who does the work, and where work is done. To create value from these changes, organizations should take a broader perspective.

The future of work: What does this term really mean? Much discussion has focused on artificial intelligence and whether or not robots will take our jobs, but cognitive technologies are only one aspect of the massive shift that is under way. To understand what’s going on and, more importantly, what we can do about it, it’s important to consider multiple converging trends and how they are already fundamentally changing all aspects of work—with implications for individuals, businesses, and society.

We define the future of work as a result of many forces of change affecting three deeply connected dimensions of an organization: work (the what), the workforce (the who), and the workplace (the where) (figure 1).

Learn More

Browse the Future of Work collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

The new realities created by these forces of change present us with complex questions to consider—including ethics around human-machine collaboration, how we plan for 50–60-year careers,1 and how we unleash organizations through a continuum of talent sources. As Thomas Friedman has observed, “What’s going on is that work is being disconnected from jobs, and jobs and work are being disconnected from companies, which are increasingly becoming platforms.”2

In this article, we provide an overview of the forces of change that are driving the evolution of work, workforces, and workplaces, and offer a perspective on how organizations should begin to respond to the new challenges unfolding. Organizations today appear to have an unprecedented window of opportunity to shape what ultimately becomes the future of work.

Work: What will the work look like?

This isn’t the first time that the western society has completely changed its cultural idea of work. In the preindustrial economy, work was synonymous with craftsmanship, the creation of products or the delivery of complete outcomes. The craftsman took end-to-end responsibility for delivering the product or outcome—a cobbler, for instance, would do everything from measure the customer’s feet to make final adjustments in the finished pair of shoes. The industrial revolution changed this conception of work, as industrialists realized that products could be manufactured faster and cheaper if end-to-end processes were atomized into repeatable tasks in which workers (and, later, machines) could specialize. The notion of a “job” became that of a collection of tasks, not necessarily related to each other, rather than an integrated set of actions that delivered a complete product or outcome.3

Now, as we step rapidly into the cognitive revolution, we once again appear to be redefining work to create valuable human-machine collaborations, shifting our understanding of work from task completion to problem-solving and managing human relationships.4 Technology has already begun to change the way we organize tasks into jobs: For example, robotics and robotic process automation have transformed manufacturing and warehouses, and digital reality technologies are helping workers transcend limitations of distance and who is assigned to which task. According to the World Economic Forum, the division of labor between people and machines is expected to continue to shift toward machines, especially for repetitive and routine tasks.5 That could eliminate upward of 14 percent and disrupt 32 percent of today’s jobs, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCED).6

However, there is evidence that these technologies could be used to augment the efforts of the workforce rather than replace them—in fact, in a 2018 report the World Economic Forum projected that while nearly 1 million jobs may be lost, another 1.75 million will be gained.7 The jobs of the future are expected to be more machine-powered and data-driven than in the past, but they will also likely require human skills in areas such as problem-solving, communication, listening, interpretation, and design. As machines take over repeatable tasks and the work people do becomes less routine, roles could be redefined in ways that marry technology with human skills and advanced expertise in interpretation and service.8 Techniques such as design thinking can help organizations define roles that incorporate the new types of capabilities, skills, activities, and practices needed to get the work done.

To make all of this happen successfully, we will likely need to change the way we conceive of work and develop the training our workforce needs to take on these new roles and assignments. Otherwise, we could find ourselves weighed down trying to apply legacy concepts and skills onto the new and quickly emerging world of human-machine collaboration.

Workforce: Rethinking talent models

Not only have workforce demographics changed over the last 30 years—collectively making the workforce older9 and more diverse10—but the very social contract between employers and employees has altered dramatically as well.11 Organizations now have a broad continuum of options for finding workers, from hiring traditional full-time employees to availing themselves of managed services and outsourcing, independent contractors, gig workers, and crowdsourcing. These newer workforce types are available to solve problems, get work done, and help leaders build more flexible and nimble organizations (figure 2). Alternative workers are growing in number; currently, 35 percent of the US workforce is in supplemental, temporary, project, or contract-based work.12 This percentage is growing as well—for example, freelance workforce is growing faster than the total workforce, up 8.1 percent compared to 2.6 percent of all employees.13

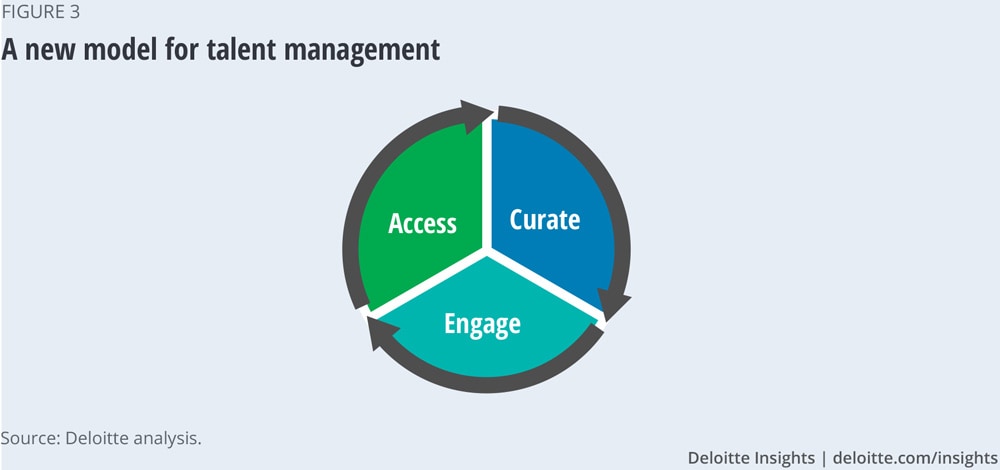

As labor-sourcing options increase, it opens up the possibility for more efficiency and creativity in composing an organization’s workforce. But with more options often comes more complexity. Employers should not only consider how roles are crafted when pairing humans with machines, but also the arrangement of their human workforce and what type(s) of employment are best suited to obtain the creativity, passion, and skill sets needed for the work at hand. Orchestrating this complex use of different workforce segments might require new models. It could fundamentally change our view of the employee life cycle from the traditional “attract, develop, and retain” model to one where the key questions are how organizations should access, curate, and engage workforces of all types (see the sidebar, “Beyond the employee life cycle”).

Organizations have an opportunity to optimize the organizational benefits of each type of talent relationship while also providing meaningful and engaging options for a wide variety of worker needs and motivations. However, making the most of the opportunity could require a complete rethinking of talent models in a way that allows organizations to carefully match people’s motivations and skills with the organization’s work needs.

Beyond the employee life cycle

Organizations have long thought of talent management as how to approach attracting, developing, and retaining top talent. As new, alternative work arrangements come on the scene, we anticipate that this model could shift to:

- Access. How do you tap into capabilities and skills across your enterprise and the broader ecosystem? This includes sourcing from internal and external talent marketplaces and leveraging and mobilizing on- and off-balance sheet talent.

- Curate. How do you provide employees—ecosystem talent—and teams with the broadest and most meaningful range of development? This includes work experiences that are integrated into the flow of their work, careers, and personal lives.

- Engage. How do you interact with and support your workforces, business teams, and partners to

- build compelling relationships? This includes multidirectional careers in, across, and outside of the enterprise; and for business leaders and teams, providing insights to improve productivity and impact while taking advantage of new ways of teaming and working.

Workplace: Rethinking where work gets done

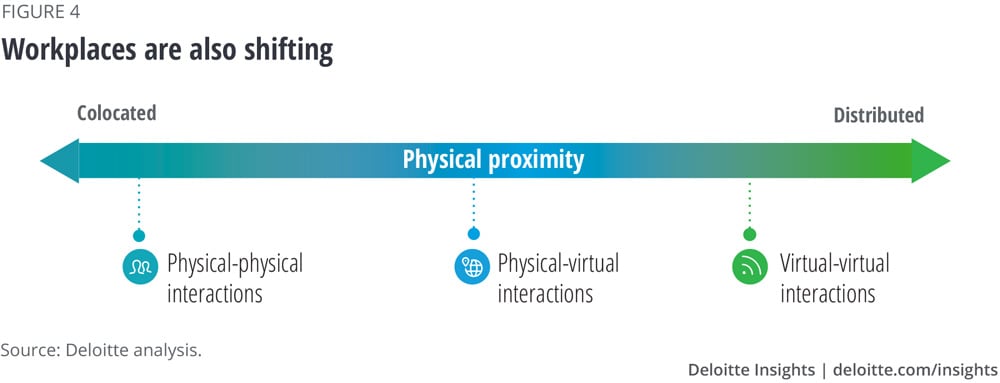

As the “who” and the “what” of work shift, so does the workplace. Where once physical proximity was required for people to get work done, the advent of digital communication, collaboration platforms, and digital reality technologies, along with societal and marketplace changes, have allowed for and created the opportunity for more distributed teams.14 Organizations are now able to orchestrate a range of options as they reimagine workplaces, from the more traditional colocated workplaces to those that are completely distributed and dependent on virtual interactions (figure 4).

Again, changing the physical workplace should not be seen simply as an opportunity to increase efficiency or to reduce real estate costs. Workplace culture is highly connected to both innovation15 and business results,16 and as teams become more distributed, organizations might need to rethink how they foster both culture and team connections.

The importance of these connections should not be understated. As Yale School of Management professor Amy Wrzesniewski has observed, “In previous generations, people would spend decades and even their entire careers embedded in the same organization. In those cases, the sense of membership buoyed both individuals’ identities and their psychological health.”17 For employers, this implies a need for more explicit attention to creating connections and community as workplaces become more virtual and filled with more contingent workers.

The opportunity: Making the future of work more valuable and meaningful

Shifts in work, the workforce, and the workplace are deeply interrelated. Changes in one dimension can have important consequences for both workers and employers that have not had to be considered before.

What the future of work ultimately looks like isn’t a foregone conclusion. We seem at a crossroad in redefining what it means to work, to be an employer, and to contribute value and talent in newfound ways. Purpose will bring the future into focus. We can choose to use advances in technology merely to drive more efficiency and cost reduction, or we can consider more deeply the ways to harness these trends and increase value and meaning across the board—for businesses, customers, and workers.18 Taking too narrow a view could be the big risk.

To succeed, organizations should zoom out19 and imagine the possibilities so that they can compose work, the workforce, and the workplace in a way that increases both value and meaning while taking advantage of the opportunities for efficiency we have at hand. We see three actions for employers to consider in directing the forces of change:

- Imagine. Imagine the possibilities of the future by leveraging industry-specific data analytics and insights to define your ambition and strategy for transforming the workforce for the future. Set goals for the future of work that reach beyond cost and efficiency to include value and meaning.

- Compose. Analyze and redesign work, workforce, and workplace options that take advantage of the value of automation, alternative talent sources, and collaborative workplaces.

- Activate. Align the organization, leadership, and workforce development programs to access skills, curate next-generation experiences, and engage the workforce of the future in long-term relationships and business leaders in new ways of working.

To do these things well, we, as employers, should activate the workforce and use technology in ways that generate broad and valuable benefits for our organizations and for society. We have the opportunity to create a preferred future for meaningful work for all. It’s ours to shape.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Future of Work

-

Future of work Collection

-

What is work? Article6 years ago

-

Engaging employees like consumers Article6 years ago

-

Purpose, passion, and independent work Article6 years ago

-

You snooze, you win Article6 years ago

-

Designing work environments for digital well-being Article7 years ago