Building the peloton High-performance team-building in the future of work

26 minute read

01 July 2020

As organizations increasingly come to operate as networks of teams rather than as hierarchies of teams, five factors supporting team effectiveness can help such teams flourish.

A team of teams

Sport is a popular—if not the most popular—analogy for teamwork in business. Much has been learned by drawing parallels between the two: the importance of well-defined roles, the relative benefits of specialist versus generalist, the need for a shared goal, and so on. It would be easy to conclude that there’s little left to be learned from sport. Unless, that is, we expand our view to cover the peloton—the team of teams that participates in a major cycling event such as the Tour de France: a collection of distinct teams simultaneously competing and working in concert against a common enemy, fatigue, toward a single destination, analogous to the way teams work in a modern organization. Each team works as an integrated unit, but so does the team of teams1—the firm, the business peloton—in the endless quest for productivity and opportunity in a complex and uncertain market.

Learn more

Explore the future of work collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Whether through a deliberate effort to “keep pace with the challenges of a fluid, unpredictable world,”2 or inadvertently as a result of efforts to disrupt the edge, firms are building cross-cutting teams to address specific issues or drive innovation, transforming themselves into networks or ecosystems of teams.3 Firms that do manage to adapt are establishing themselves as the market leaders.4 New winners and losers are being created as we write.

The question is then: What can leaders learn from this analogy to create high-performing teams and build their peloton? In the pages that follow, we explore the changing nature of teams in today’s business environment, examining how the analogy of a cycling peloton can help us to better understand how teams function in a modern organization. We posit five conditions necessary for team effectiveness in a modern business peloton. Together, these conditions position teams to operate effectively with a workforce that covers a spectrum of worker types within a workplace that is no longer dictated by physical proximity to undertake work that may be automated and done by—and with—smart machines.5

The changing nature of teams within the organizational construct

Teams have long been part of a firm’s organizational chart, with team leaders holding a formal role in a firm’s governance hierarchy with the team there to support them. Teams have traditionally consisted of individuals from the same business unit, while those working in other units play for other teams. This has been true whether the organization design is process-, function-, segment-, or product-based. These teams rely on strict lines of authority and accountability to govern their operation, and are built on highly optimized (but static and difficult-to-change) processes designed for scalable efficiency.6 This is business conceived as mass production—problems are decomposed into well-defined tasks, each assigned to a specialist who has authority and autonomy within their specialization, while interactions between specialists are tightly defined.

However, the challenges confronting firms today are more complex than those in the past. They cut across operational and organizational groups rather than being focused within a single one. Globalization and the development of online markets have enabled firms to address a global wealth of niches rather than a single geography. At the same time, the technology providing this global reach is enabling firms to unbundle themselves,7 transforming the vertically integrated enterprises that characterized much of the Industrial Revolution into an ecosystem of suppliers and partners,8 with the firm at the center.

This unbundling unlocks cost efficiencies and agility but is in tension with customer behavior, as customers are increasingly coming to expect a coherent, joined-up experience during their buying journey as they skip between locations, media, geographies, and channels, regardless of which member of the firm’s ecosystem they’re interacting with. The digital business environment also has lowered barriers to entry and enables innovation to travel faster, driving firms to become more agile so that they can react to the problems and opportunities they encounter in a timely manner—no easy feat when dealing with the many partners and suppliers inherent with a modern business, and the contractual inertia that this creates.

While teams defined relative to an organizational structure have served firms well in the past, they are not suited to the rapidly evolving and inherently digital business environment we’re in today. Their internal focus, bureaucratic nature, and resistance to change hinder customer-centricity, cross-functional collaboration, diversity of thinking, rapid scaling, and agile ways of working.

What is a team?

Teams consist of interdependent members working on a shared goal. A team is distinct from a workgroup or coalition, which typically consists of more members whose work is not interdependent.

Firms are responding to the challenges they face today by forming cross-silo and cross-organization teams, deconstructing fixed organizational structures by breaking up functional domains, separating teams from traditional management structures, and opening up the definition of “who is my team?” so that they can pull together the diverse skill sets and perspectives these challenges require. Specialist teams are being deployed to address innovation challenges and in-demand technical expertise (a growing trend, though the approach is not new). It is also common for organizations to maintain pools of employees without operational roles, who instead work on an endless series of projects and innovation challenges.9

A few examples illustrate this phenomenon in action. Category management10 has enabled retailers to increase sales by handing much of the responsibility for managing a category of goods (bathroom fittings, for example) to a cross-organizational team, one often led by a supplier (rather than a member of the firm’s workforce), a category champion, rather than an employee. Marketing departments are creating cross-functional tiger teams to deliver special product offers—such as a burger of the month—at a faster pace than operations and a firm’s formal supply chain can support. Communities of practice (CoP) and communities of excellence (CoE)—teams that span the enterprise—are used to support the adoption (and exploitation) of new technologies or methodologies. Project teams—the traditional vehicle for delivering business change—are becoming more prevalent as automation shifts a firm’s efforts from operations (which are increasingly automated) to the business change and improvement projects delivered by teams

Cross-functional and cross-organization teams are rapidly becoming the driver of productivity in firms. However, the consequence of this deconstruction is that documented reporting lines and functional or geographical divisions are becoming increasingly disconnected with how work is actually done. A 2019 ADP Research Institute study of 1,000 workers from 19 countries11 found that of employees who worked on more than one team, “three-quarters said their additional teams didn’t show up in the directory,”12 suggesting that a significant volume of work and worker relationships aren’t visible on organization charts.

In this environment—where companies are moving beyond traditional structures and there is recognition that rigid boxes and lines do not reflect the reality of work—it’s useful to think of the organization as a team of teams, a peloton, analogous to a peloton in a cycling race.13

A peloton is a team of teams rather than a hierarchy of teams. Its structure is fluid and self-organizing rather than rigid and imposed from without. Individual teams work according to their own strategy and plan, but not in isolation from the teams around them. Cyclists within a peloton are able to exploit the reduction in drag created by another rider’s slipstream and benefit by expending less energy, a technique crucial in the management of fatigue in endurance cycling events. Relationships among teams within the peloton are not formally defined or rigidly fixed. Instead, they are informal and self-organizing, negotiated and renegotiated as circumstances change. The whole peloton—the organization—is a collection of teams that need to work in concert to battle fatigue and achieve their ultimate objective.

Four types of business teams

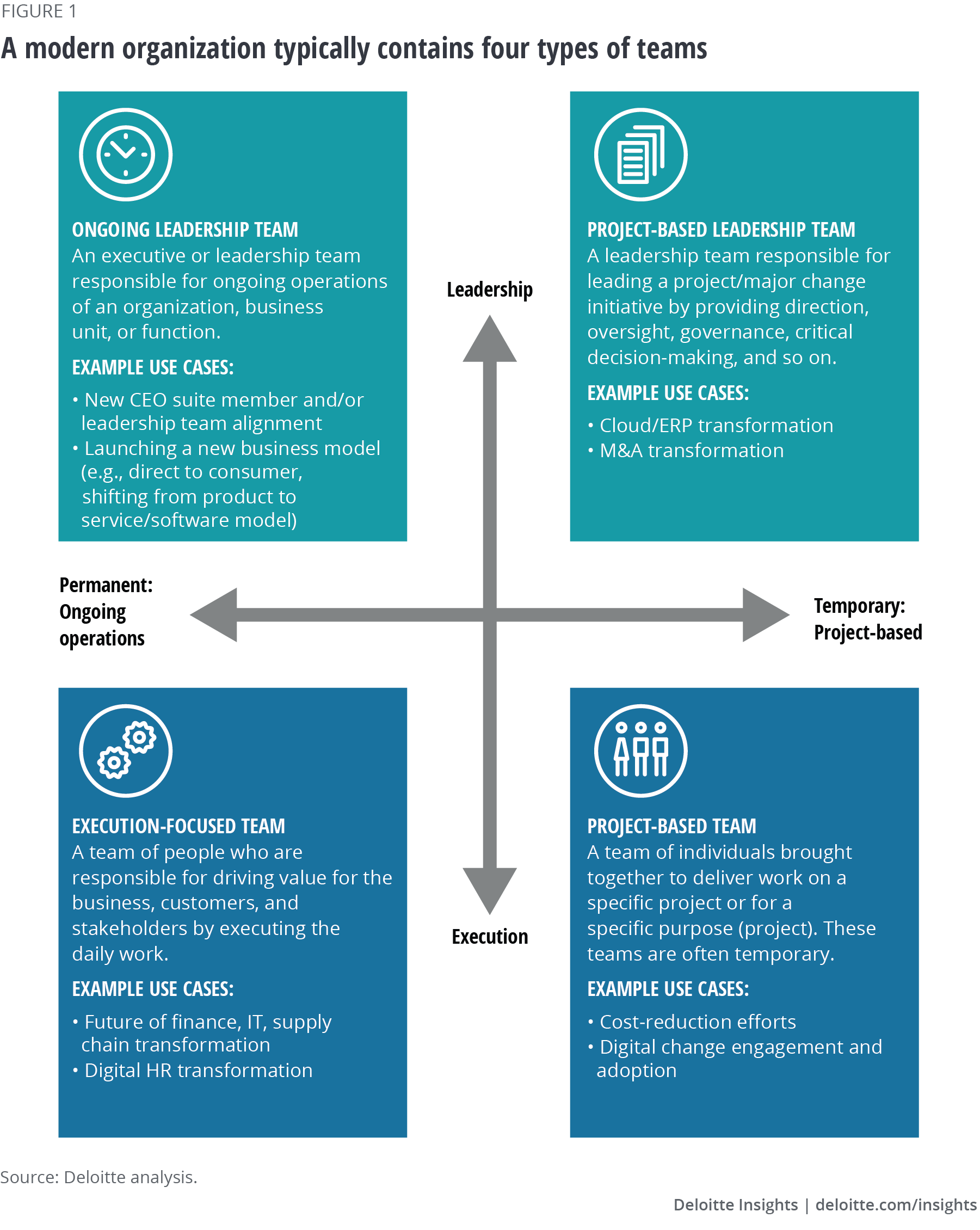

Whereas a cycling peloton only has a single type of team, teams in an organization vary along two dimensions—leadership versus execution, and projects versus operations—that enable us to organize them into four different types.

The ongoing leadership team is perhaps the most easily identifiable type. Executive, divisional, or geographical leadership teams are, as the name suggests, typically stable over the medium to long term. Ongoing leadership teams are an enduring part of firms, integrating the expertise from across the business required to direct the firm.

Project-based leadership teams (and the project-based teams they lead), on the other hand, exist for a set period of time to achieve a specific objective. They are formed at project inception, provide direction, oversight and governance, and then dissolve when the project concludes. The team’s level of seniority is determined by the scale or significance of the project and, like an ongoing leadership team, may comprise a range of functional backgrounds. A key challenge for project-based teams can be the speed at which they must form, norm, and perform.14 The requirement for teams to rapidly form, perform, and then disband is only increasing.

An execution-focused team exists to drive ongoing value for the organization, its customers, and other stakeholders, giving the team an explicit operational focus. Like the ongoing leadership team, execution teams are not attached to a particular initiative, and are most commonly associated with a persistent functional need, such as HR or sales. Execution-focused teams are oriented to a particular aspect of delivery or support and may also be referred to as a frontline workgroup due to their typical proximity to the “frontline,” which for most organizations would refer to the customer. Such groups are often the first within an organization to experience disruption and are therefore well-positioned to see and potentially learn from and adapt to change.15 Of all types of teams, execution-focused teams are most likely to undergo continuous change as increasing automation pressures, customer drivers, and end-to-end service delivery models require a continuous redefining of the team.

Finally, there are also “hidden” teams which, by their elusive nature, are tricky to categorize neatly. These are informal teams that may not be visible on organizational charts yet may be responsible for a significant portion of the work an organization undertakes.16 For instance, a leader may have an informal team of advisers that they rely on, a middle manager may support an informal team to grow a capability, or a junior worker might form an informal team to share knowledge.

Building an effective team within the business peloton

Today’s business teams—like the teams in a cycling peloton—need to be autonomous, adaptable, disciplined, productive, and continually improving how they deliver results, as well as intrinsically connected to the work of other teams across the organization. This raises the question: Are the factors that we’ve long considered integral to team success (clear direction, good communication, distinctive roles) still relevant? What does a successful team look like within the flexible and dynamic business peloton?

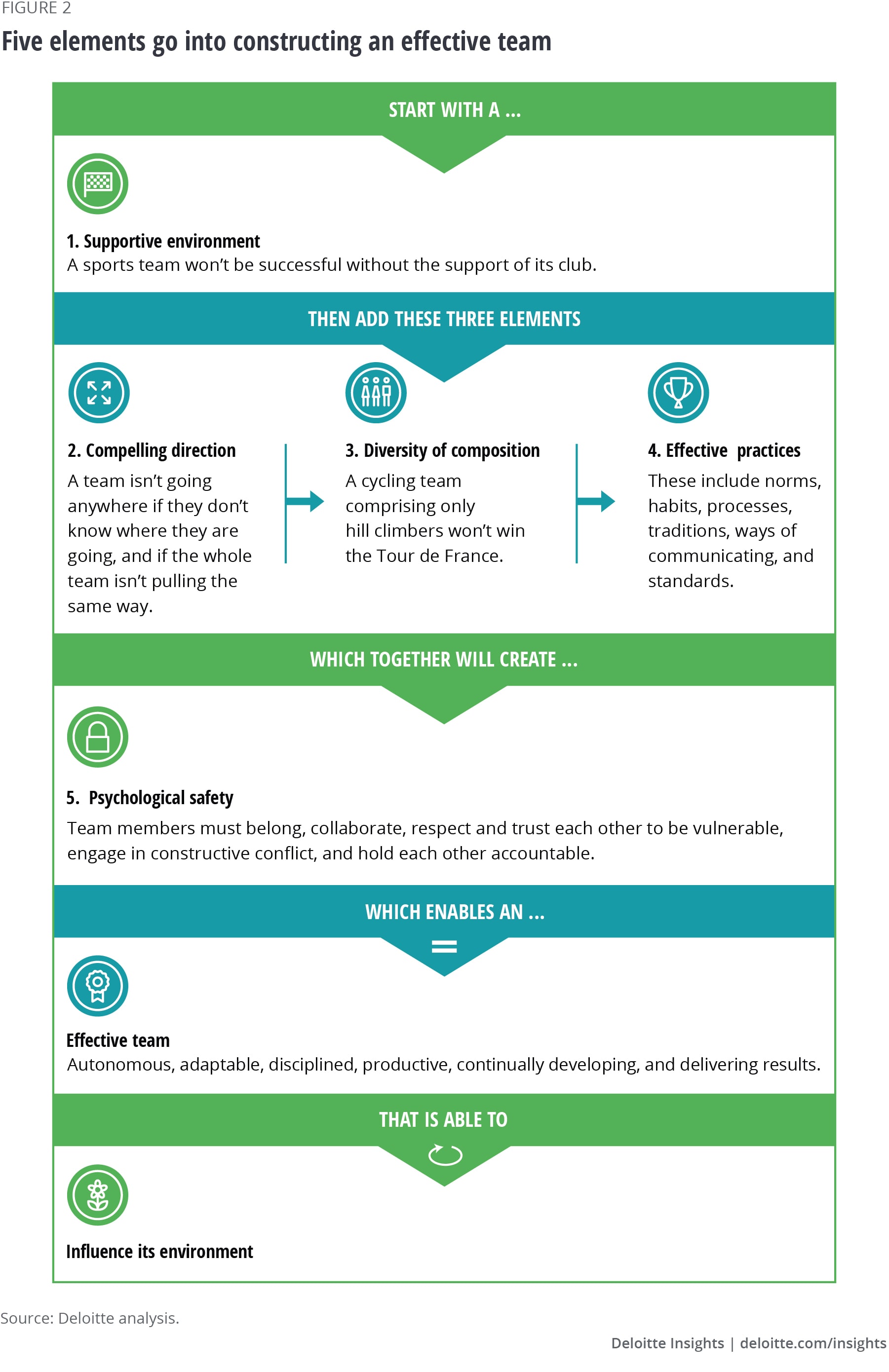

While every team is unique, each requiring its own recipe for success, it is possible to make generalizations about what makes teams successful. Below, we explore the five conditions we consider essential to enabling team effectiveness within the business peloton:

- A supportive environment

- A compelling direction

- Diversity

- Effective practices

- Psychological safety

Creating a supportive environment

A team in a cycling peloton relies on more than the athletes actually cycling. It includes others, such as mechanics and even the soigneurs,17 who are there to support the cyclists. Many of these support personnel follow the cyclists on the racecourse to ensure that support is available when it is most needed. The team and, in particular, the team member who crosses the finish line first, cannot succeed unless all these moving parts work in concert, including domestiques creating slipstreams and conserving the energy of select riders, mechanics following along behind the peloton to fix broken equipment just in time, and the directeurs sportifs strategizing each stage of the race.

All this is to highlight that a team in a cycling peloton cannot succeed unless it has a supportive environment. The environment is the workplace where the team operates, the social and physical context of the work, and the ecosystem that the team is part of. Creating a supportive environment is one of the team manager’s most important responsibilities, and is the first task they should focus on. The same is true in business. While it might be tempting to first focus on factors within the team as determinants of its effectiveness, the environment that a team operates within is key to its success and cannot be ignored. The environment is the team’s foundation, and shoddy foundations will result in a poorly performing team.

Creating a supportive environment can be a major challenge for a team that cuts across organizational boundaries. The disconnect between cross-functional and cross-organizational teams and current organizational models—the “outside the org chart” nature of these teams—creates resourcing and governance challenges. Such teams, therefore, need to pay particular attention to ensuring that they have the tools, information, and cultural conditions (such as senior leadership endorsement, or shelter from a risk-averse organizational culture for a team charged with innovation) that align with their purpose. The specifics of a supportive environment will be dictated by the team’s purpose. For a project-based team within a large organization, for instance, a supportive environment might include appropriate funding, freedom to act (within political constraints), and colocation of team members or sufficient tools to enable virtual collaboration.

Elements of a supportive environment can include:

- Tools (typically technology and platforms) available to the team

- Resources (money, though also nonmonetary resources)

- Information (typically data)

- Imposed structures (performance schemas are a good example)

- Intergroup cooperation (such as limiting or eliminating “transaction” costs)

- Organizational culture aligned to the teams

- An appropriate level of autonomy

- Favorable conditions (including economic conditions)

It is particularly important that the team’s environment be compatible with its purpose, direction, and practices (factors that we will shortly explore). For example, some teams must navigate the tension between improving value for customers while also cutting costs. Similarly, a team focused on innovation must navigate the tension between prescriptive processes and creating new practices. A cross-functional team will also struggle if the performance metrics of team members are aligned to their home function and misaligned with the team’s objective.

Many environmental factors will be beyond a team’s control. In other areas, the team may be able to influence the environment, or at least protect itself from the effects of negative environmental factors. Acting as a virtuous cycle, success will allow a team to have a greater influence on its environment. It often falls to a team’s leader to act as a conduit between the team and its external environment, taking responsibility for ensuring that the team has adequate support, though that responsibly shouldn’t sit solely with the leader. It should be dispersed throughout the team—for example, the members of a cross-functional team may need to act as conduits back to their respective functions to source knowledge and support.

Common roles in a road cycling team

Domestiques: Cyclists who play a supporting role for a select race stage, often creating slipstreams to conserve the energy of the team leader.

Soigneurs: Noncycling members of the team who support the cyclists with massage, food, and other assistance during a race.

Team leader: The team’s strongest all-rounder cyclist who has the best chance of winning the event.

Team captain: An experienced cyclist who plays a management-like role within the cycling team while on the road.

Team manager: Oversees the management of the broader cycling team, not limited to the cyclists, to manage operations, including sponsorships and the event program.

Director sportif: Supports team members who dictate the cyclist’s race strategies, often accompanying the peloton in cars.

Climbers: Cyclists whose strength is hill-climbing and who support the team leader in steep terrain, or contest to win hilly stages.

Sprinter: Cyclists whose strength is speed over flat distances. In the Tour de France, these riders contest for the green jersey, which is awarded for points from stage winds and intermittent sprints.

Mechanics: Supporting team members who are responsible for maintaining the bikes and spares. The mechanics work demanding hours on tour, carrying significant responsibly for the essential equipment and technology and needing to be ready to assist at a moment’s notice during the race.

Establishing a compelling direction

With the foundation in place, the next factor to focus on is the need for a team to have a compelling direction: This is what we’ll achieve and this is how we’ll achieve it. The direction is the reason a team exists—its vision, mission, goals, or aspiration. It provides a purpose for the team members to rally around, and shapes both the team’s strategy and tactics.

In a cycling peloton, each team’s direction is obvious: to win the race. All team members view their contribution to the team relative to this goal. But a cycling team’s direction also includes interim goals—such as obtaining the green jersey18 or winning a difficult mountain stage—as steps toward achieving the overall goal. Interim goals provide rallying points for team members, helping them understand how they will help the team toward the long-term goal. The team’s direction covers both the intended destination and the path taken to get there. There is a clear distinction, for example, between a team that intends to win the race (the ultimate goal) by hard work and close shepherding of resources, or one that intends to have superior technology, and a team that intends to win the race by scientifically exploring the limits of human performance (via doping).

Similarly, in business, a team’s direction must also be both long- and short-term. Long-term direction might be captured in a formal purpose, vision statement, or aspiration: something for team members to rally around. Short-term direction may be captured by goals or frameworks such as key performance indicators (KPIs) or objectives and key results (OKRs) that describe how the team will make intermediate progress to reach their long-term overarching direction.

A clear direction provides team members with an anchor for their commitment to the team. Consequently, they should be framed in ways that encourage team member buy-in. It has long been accepted that an effective direction must be clear and challenging but achievable. Recent thinking also highlights the importance of the direction being meaningful and ethically aligned, as the workforce is becoming increasingly purpose-driven.19 To align with the team’s direction, team members must not only understand the mission, but be willing to support it—something that may be largely dependent on the compatibility of their own desires and preferences. Traditionally it’s the team’s leader who provides, inspires, or drives a team’s direction; however, a team might also be self-directive, with distributed leadership increasingly recognized as an enabler of team effectiveness.20

A clear and compelling direction also helps a team understand how it should relate to other teams within the peloton or firm, where collaboration might be fruitful, and where the team should work (and negotiate) with others. Teams need the flexibility to respond to the local conditions and their relationship to other teams. It may be advisable for teams in a business peloton to set their own goals and success criteria within overarching strategic parameters established by management. The importance of a compelling direction is further heightened for cross-functional teams, which are likely to be faced with company politics and an environment of competing priorities. Without a strong direction, ideally at a strategic company level, a cross-functional team is unlikely to drive through silos to achieve their objective.

Fostering diversity

Having dealt with how our team functions within the peloton—by establishing a supportive environment and compelling direction—we can turn our attention to how team members function within the team.

To be most effective, a team’s direction should be:

- Clear

- Challenging

- Achievable

- Consequential

- Engaging

As with any team sport, the teams in a cycling peloton rely on a variety of specialists, such as sprinters or climbers (although this is not to imply that the generalists are not important; all-rounders are the team leaders with the best chance of winning). Diversity—the level of difference or heterogeneity—within the team is an important differentiator between successful and unsuccessful teams, as it can ensure that teams have access to the different capabilities and points of view they require.21

Diversity within a team operates at a number of levels. The first and the most visible type of diversity is the different roles within a team, the specializations—analogous to a cycling peloton’s sprinters and climbers. In a traditional hierarchical organization, the most senior member of the team will lead it, parceling out tasks according to each team members’ position in the team’s hierarchy. In a modern workplace, however, team roles are rarely dictated by position titles. Instead, they are dynamically divided and assigned based on the skills and capabilities each person brings to the team and their fit with the team’s needs at the moment.

A cycling team’s “team leader” role—as distinct from “team captain”—gives an example of the different types of leadership roles required within a cycling team. (These two roles are often merged in a traditional business team, a team anchored in a firm’s organization chart via a manager.) Team captains provide guidance to the team while on the road, using experience and local knowledge to adjust the strategy, and liaising with the directeurs sportifs.

The role of the team leader, while generally held by the strongest all-rounder, might be fulfilled by whoever is best positioned to win a particular race or race stage. A team’s best climber may lead a hilly stage, but would not be as qualified to lead during flat stages where the team’s best sprinter would take the lead.

A second, deeper level of diversity (in business) is based on identity (or demographics), such as gender, age, ethnicity, or socioeconomic factors. This is analogous to the need for local knowledge in a cycling race, where our cycling team might benefit from having members with a deep knowledge of the different roads that the race will pass along. For business, diversity of identity gives a team the ability to tap into different viewpoints and lived experiences—tacit knowledge that can greatly enhance effectiveness in working with the diverse set of stakeholders (both internal and external) that a team must typically deal with.

There is also a third level of diversity: cognitive diversity.22 This refers to the diverse ways that individuals can approach and think about problems.23 In business, cognitive diversity is often tied to the business area or discipline in which a person has the most experience. A team of accountants, for example, is likely to frame all problems as accounting problems and assume accounting solutions.24 A cognitively diverse team of accountants, engineers, anthropologists, and skilled tradespeople will be forced to develop a multidisciplinary understanding of what the problem is, and will likely come up with a superior, and multidisciplinary, solution.

A diverse team should ideally draw on a broad range of stakeholder groups, including a mix of capabilities, disciplines, personalities, risk appetites, and cognitive styles; that is, it should have role, identity, and cognitive diversity.

There are a few caveats about greater diversity supporting higher performance. First, diversity will only be beneficial if it is enabled and reinforced by effective practices throughout a team’s life cycle, uniting the diverse team rather than allowing the team’s differences to tear it apart. Second, a team’s role diversity must also be complementary: Consider the problems likely to arise on a cycling team consisting of only climbers, a soccer team composed of eleven goalies, a ship crewed only by captains, or an executive board consisting only of financial experts. Third, it goes without saying that adding a skill set completely divorced from the team’s purpose will have limited value. Finally, the benefits of role, identity, and cognitive diversity need to be balanced with the feasibly of team size and any fixed composition requirements.

Installing effective practices

Practices are the actions that glue a team together and facilitate high performance.25 They are the actions, large or small, that teams undertake either regularly and consistently (the team’s “habits” or “rituals”) or occasionally. They are the unspoken norms that team members default to both consciously and unconsciously to regulate their behavior.

In many cases, a team’s practices might be unremarkable, but as a whole and applied consistently by all team members, their influence on the way that the team performs is significant.26 Sir Dave Brailsford, the head of British Cycling from 1997 to 2014, is credited for turning the struggling team around through tiny improvements across every aspect of the team; for example, by ensuring that the team undertook the practice of properly washing their hands like a surgeon would, the team would reduce the risk of illness during a competition.27

Successful teams develop practices that allow them to effectively interact with their environment, including collaboration with other teams. This might involve regularly showcasing work to other teams, giving team members the opportunity to spend time with and learn from other teams or building stakeholder confidence and support with regular communication of risks, issues, and progress. Practices that a team undertakes to facilitate the setting of direction and tracking toward goals may help set the team up for success by cultivating shared commitment and driving accountability. A team’s practices can also have profound benefits to the team’s ability to incubate and utilize diversity by creating a climate where differences of thinking are valued, and individual team members feel safe to share their views (something we will explore in more detail next).

While it is clear that successful teams have effective practices, there are no objective rights or wrongs when it comes to what these practices are. A practice that is effective and enables success for one team might not be appropriate for another. For example, a regular sales conference call at 8 a.m. on Monday might help a team organize itself at the start of a busy week, but could disenfranchise team members who have family responsibilities such as school drop-off. Similarly, a daily stand-up meeting can be effective for a cycling team (or a project team) preparing to head off for the day, but might cause problems for a leadership team dealing with significant business travel. Even for similar types of teams, a practice that is effective for one team may not suit the working styles or cultural preferences of individuals in another.28

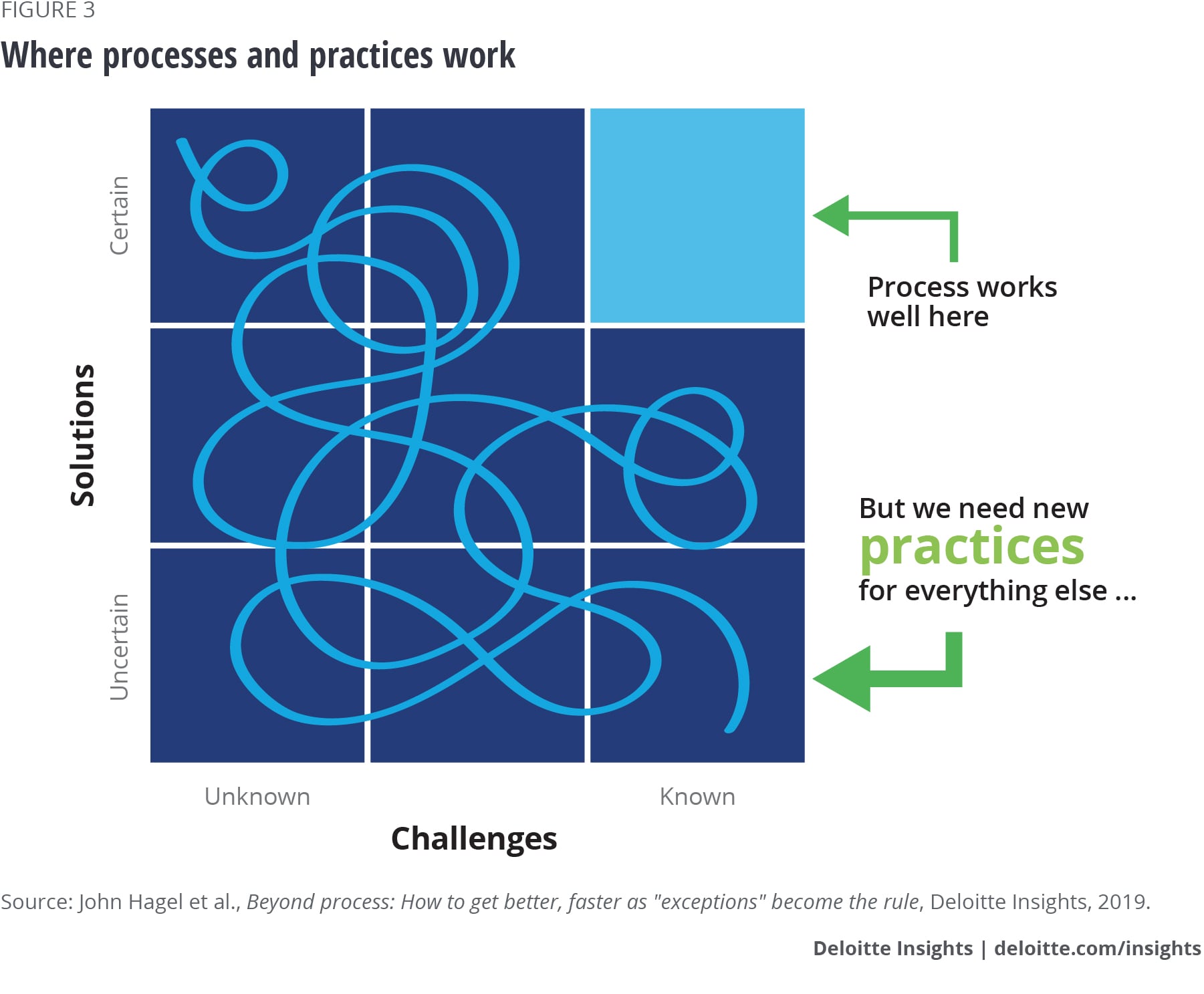

It’s important here to distinguish between practices—tacit and context-specific approaches to finding solutions to particular problems, the way that work is actually done—and processes, which are standardized series of tasks that provide well-defined outcomes for idealized problems. For teams that are responsible for work of a sequential and tried and tested nature, orchestrated processes will organize and optimize tasks for efficacy. A frontline execution team—for example, a team within a call center—will benefit from processes that standardize the management of queries to create efficacy and ensure an appropriate standard of service. However, in a world where challenges are more ambiguous, and solutions less certain, teams are increasingly asked to deliver in a more spontaneous way, in shifting and unpredictable environments.

Creating psychological safety

Our final factor is the most intuitive, and it is well supported by research: A team must have a culture of trust, cohesion, and psychological safety if it is to succeed. This is the heart of a good team; it is the elusive magic or x-factor that separates some teams from others. The absence of psychological safety can result in problems and conflict being hidden and going unreported, as team members don’t feel that they can speak up. Cycling’s problems with doping, for example, would have come to light much earlier if individual cyclists had felt comfortable in coming forward. A similar phenomenon was seen in finance firms, with executives unaware of the depth of their firm’s problems until a formal government inquiry was launched.29

A climate where team members feel a sense of inclusion creates conditions for high team performance by enabling individuals to speak their mind without fear of judgment or reprisal and, therefore, to effectively collaborate and encourage creativity.30 A team’s ability to take risks, something that is particularly important for some kinds of teams (such as those with an objective to innovate), relies particularly on team members’ need for psychological safety being met. It is only after a level of trust and inclusion is established that a team can engage in constructive conflict—essential if a team hopes to be honest and bold—and hold each other accountable to their commitment to the team’s objective.31

Google’s Project Aristotle provides some of the most compelling evidence for the importance of psychological safety within a team. Despite combing “through every conceivable aspect of how teams worked together—how they were led, how frequently they met outside work, the personality types of the team members,” the only significant pattern that Project Aristotle could discern was a correlation between team members feeling psychologically safe and team performance.32

Team leaders and all members can foster psychological safety within teams by demonstrating commitment to the team’s direction and reinforcing practices that create a sense of belonging and enhance cohesion. While a team’s specific practices should be unique to the team, certain fundamental practices—such as allowing all members to have a voice during meetings, ensuring that the whole team is acknowledged for its successes, and encouraging members to critique each other’s ideas rather than the individuals—will support the development of psychological safety, which will ultimately allow trust, constructive conflict, and accountably.

A byproduct of team success enabled by these conditions is that the team will have a greater ability to influence its environment, therefore creating a vicious cycle where a successful team is further advantaged. Within a cycling peloton, the reputation of a strong team with previous successes will attract greater funding and in turn, give it the ability to attract star riders. A successful business team may attract the attention of senior leaders, which may pave the way for additional resourcing. A team with a compelling direction will not only motivate its members but may also inspire support from beyond the team and strengthen a team’s mandate to operate within its environment. And in addition to a team’s practices promoting effective collaboration between members, a team with effective practices will also allow it to collaborate effectively with other teams, therefore further enabling team effectiveness and allowing individual teams to operate alongside other teams as a fluid and self-organizing peloton.

Effective teams in the business peloton

The factors long recognized as key to creating successful teams—of all types—have evolved as business has become more complex, driving organizations to work across departmental and organizational silos rather than within them. The peloton, cycling’s team of teams, provides a handy analogy for the way that we now need to think about building individual teams within a business peloton.

First, in both instances, it is important to establish a supportive environment and a clear, consistent, and compelling direction for a team if it is to be successful. Shayne Bannan, the general manager of Australia’s top road cycling team Mitchelton-Scott, says that one of the key priorities of the nearly 60 staff supporting 40 riders across both the men’s and women’s teams is to ensure that the team is an environment that the riders want to be a part of. Brannan describes the team as being built around its vision—to be in the top three UCI World Tour Teams—and stresses that “it’s really important that everyone has the same goals.”33 The same is true in business, as workers increasingly look for purpose-driven businesses, a firm that they feel is going somewhere they care about and which they want to identify with. Executives are taking up the challenge and developing ideas such as conscious capitalism, focused on more than the bottom line.34

Diversity is also important. Business teams have long consisted of a range of different roles, but in addition to diversity of roles, identity diversity and cognitive diversity (or diversity of thinking) are now emerging as clear differentiators between mediocre teams and those that are highly effective. This also is analogous to a cycling team, which includes riders with different strengths (such as sprinters and climbers) as well as the team captain role—which is generally filled, not by the strongest rider or the winner, but by someone who excels at looking after the team (including team morale) and its strategy during the race.

Effective practices are similarly essential to high performance in both a cycling and a business peloton. During a tour, the Mitchelton-Scott cycling team operates to an exacting schedule, carefully managing communications among riders and the wider team to ensure that all team members were on the same page. Brannan describes dining together as one of the team’s important regular practices, something that helps to relax the team and allows team leaders to pick up little issues that may later develop into problems. Similarly, in business, informal social gatherings such as team dinners are often undervalued and considered a cost, rather than appreciated as a tool to help team coherence.

Finally, the research is now abundantly clear that psychological safety is a powerful differentiator of effective teams. In a cycling context, Brannan puts it: “When riders are going down a hill at 110 kilometers per hour, they have to trust the machine.” Additionally, in an environment of intense scrutiny of supplements and nutrition, the riders have to trust the advice of the team’s nutritionists and doctors. “The best teams are the ones that have trust and belief in each other,” says Brannan. As a team operating in a high-pressure environment and with the majority of their time spent away from home, Brannan stresses the importance of a culture of care within the team. Team members who don’t feel safe will keep their problems to themselves and be unwilling to share information and effectively communicate. This lack of openness may slow a business down, preventing it from responding as agilely as it might, as collaboration and communication become impaired and individuals are reluctant to share the problems and opportunities they see. At its worst, senior executives can be left unaware of problems until they become so serious that an external regulator or government body is forced to step in.

Ultimately, getting across the finish line is a question of performance and triumph over fatigue in concert with the peloton. The successful firms—and leaders—will be those that can build and mentor the teams in their own business pelotons, making the best use of the talent and resources available in a rapidly changing and unfolding business environment.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Future of Work

-

Superteams Article4 years ago

-

A new approach to soft skill development Article4 years ago

-

Talent and workforce effects in the age of AI Article5 years ago

-

Expected skills needs for the future of work Article5 years ago

-

Inclusion as the competitive advantage Article5 years ago

-

Future of work Collection