May the workforce be with you has been saved

May the workforce be with you The voice of the European workforce 2020

10 minute read

22 October 2020

After the first phase of COVID-19, businesses are forced to chart a new path forward, building on the advances made during the pandemic. Deloitte collected the opinions of more than 10,000 workers across seven European countries to learn from their views.

Introduction

The world of work was in flux well before the COVID-19 pandemic. Long-term trends – such as proliferating new digital technologies, evolving demographics and rising social concern about inequality and the environment, often accompanied by new laws and regulations – were already changing the way work is done, who does it and where.

Learn More

Visit our collection page

Read the 2018 report

Explore the Future of Work collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

The events of 2020 have accelerated and amplified these structural changes. Unprecedented containment measures put in place to curb the spread of COVID-19 have forced companies to step up digital adoption. The realities of the pandemic have also triggered new concern for workers’ health and safety and thereby pushed organisations towards increased focus on well-being. And by exposing the vulnerabilities of various segments of the workforce and underlying inequalities,1 COVID-19 has brought ethical issues around employment to the fore and further raised the standards which companies are expected to attain. The impacts of organisations’ decisions on their communities are coming increasingly under public scrutiny. Cost-cutting plans that made sense only a few years ago now risk endangering organisations’ social licence to operate.2

As the dust settles on the first phase of the outbreak, business leaders need to do more than return to their previous activities and routines. Instead, they must chart a new path forward, building on the advances made during the pandemic. Doing so without incorporating the views of the workforce would be a missed opportunity.

To bring the voice of the workforce to the fore and learn from its views, Deloitte’s European Workforce Survey collected the opinions of more than 10,000 workers across seven European countries (see the About the research box).

Using the data, this article provides an overview of how employees have seen their working lives change in recent months. Five takeaways that stand out:

- During the pandemic many employees have experienced not just remote working but a radical shift to a more independent way of working. Organisations need to think about how to channel this increased autonomy.

- Trust, time, the network of colleagues: the `human factors’ have been more important supports than technology during the pandemic. Organisations need to consider the human and the technological together, not separately.

- Remote working seems to be here to stay. Two in three employees expect to be working remotely more often even after the current exceptional circumstances end. Organisations need therefore to reflect on the role of the workplace in their business model and articulate explicitly what benefits the office brings.

- A majority of respondents consider adaptability as a vital skill if they are to thrive in the post-COVID labour market. Organisations need to capitalise on this positive thinking and invest in developing the capabilities of their workforce. This should be done all while considering that work is not static; the nature of it is evolving just as the environmental factors that are front of mind today.

- Workers are not, however, a monolithic block. They have not all experienced the effects of COVID-19 in the same way. Nor do traditional demographic characteristics such as age necessarily offer a good guide to their thinking. Organisations need therefore to acknowledge the complexity of their workforce and design policies and interventions based on a deep understanding of workers’ attributes and needs.

This article reflects on three areas that organisations need to consider further whilst organising the return to work in a new environment. Each area will be explored in greater detail in a series of follow-up articles.

About the research

In June 2020, to amplify the ‘voice of the workforce’, Deloitte conducted the European Workforce Survey, reaching out to more than 10,000 employees across seven European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom). The survey was conducted online, and the sample was restricted to people currently employed (even if currently furloughed or on a zero-hours contract). Fifty per cent of the sample was made up of workers aged 50 or older and the other half, workers older than 18 but younger than 50. Within these two major age groups, the age and gender composition of the sample was set to resemble the current composition of the workforce in each country. Professional translators adapted the questionnaire into local languages, and native-language professionals refined the translations to optimise the comprehensibility of the questions.

Imagining a new work environment

There is little doubt that the extraordinary measures put in place in reaction to the sudden onset and rapid unfolding of the pandemic have disrupted the lives of many workers.

The value of autonomy

Almost 80 per cent of respondents to the questionnaire report that they have experienced at least one kind of change to their working lives (figure 1).3 The majority of respondents (57 per cent) identified remote working. Of these, 40 per cent had never worked remotely before COVID-19, either because the infrastructure was not in place across their organisation, or because they personally did not have access to it, or because the job could not be done remotely. Applied to all employees in Europe, these percentages suggest that more than 100 million employees switched to remote working, with almost 45 million of them doing so for the first time – all this in a shorter time frame than it normally takes to change broadband provider.

The changes workers have experienced over recent months, however, go well beyond the shift to remote working. They also encompass the work they have done and how they have done it. Only 7 per cent of those whose working lives have changed significantly during the pandemic say that working remotely was the only type of meaningful change they experienced. Employees across Europe report that their work schedule has become more flexible and that they have enjoyed greater autonomy in how they perform their work. And while this has very often been the case for those who have been obliged to work remotely (about 60 per cent), it is also true for one in five employees who continued working at their workplace.

During the pandemic, therefore, many employees have experienced not just a change in location but a profound shift in how they see their ability to contribute. As organisations head towards recovery from COVID-19, they therefore need to think about how to leverage and channel this increased autonomy and adapt their leadership style in order to monitor and guide workers’ contributions, without micromanaging.

Trust, the foundation for effective adaptation

With the exception of those who could not work at all, workers have not found change hard. More than 80 per cent of respondents report that adaptation to remote working, a flexible working schedule and greater autonomy has been easy or very easy. That appears to be the case for workers of all ages, not only for so-called digital natives. Before the pandemic, no one would have bet that such deep and sudden changes in the work environment could have been effected so successfully on a large scale – and, more than that, that workers would find it easy to adapt.

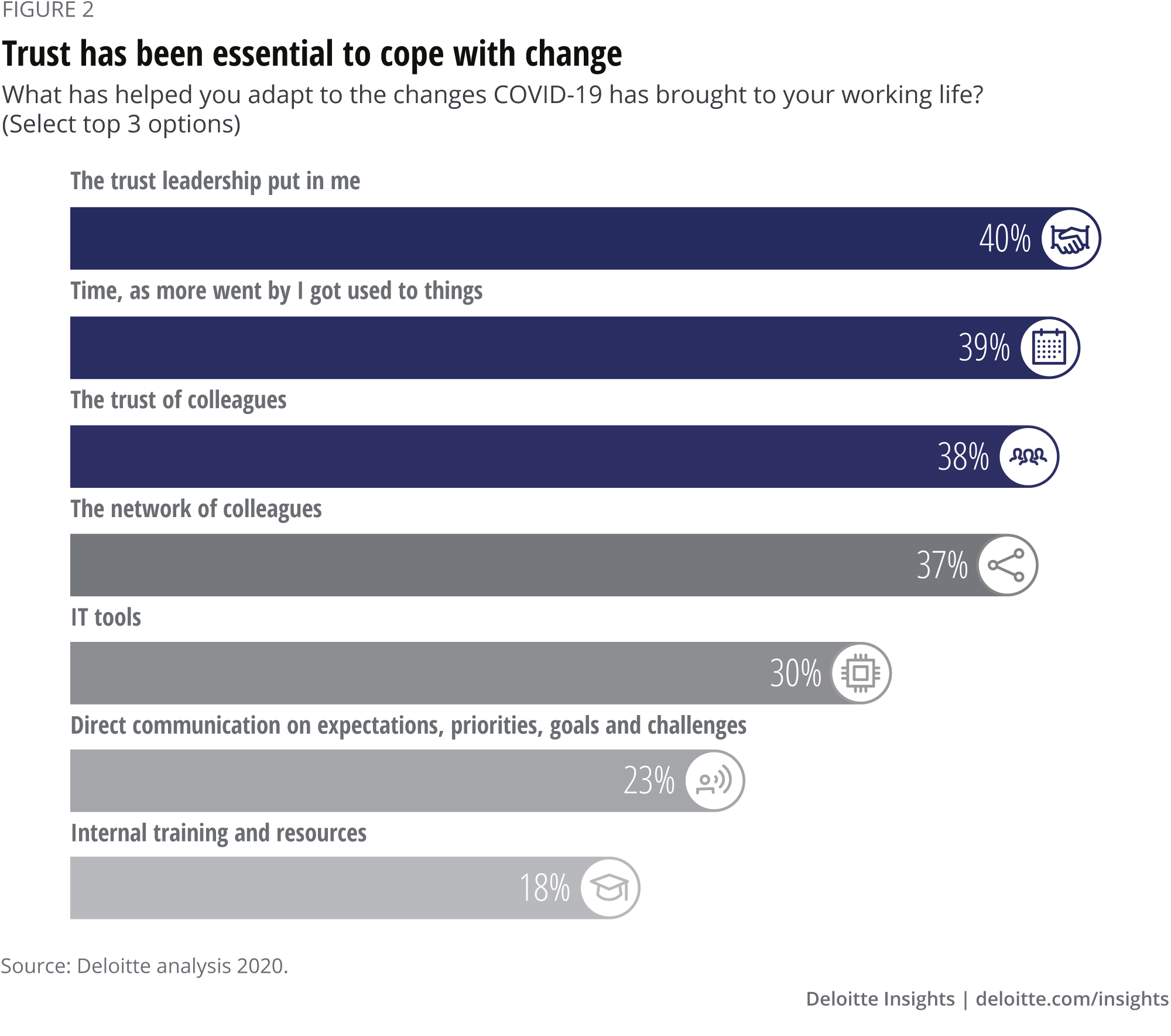

A key element has been trust, from leaders and from colleagues (figure 2). Trust is always fundamental to the healthy functioning of society and to relationships, but its importance is more readily appreciated in uncertain times. Fostering an environment of trust at work, however, requires a conscious effort from business leaders, particularly when workers are remote. A recent study suggests that a substantial number of managers question the ability of their own workers to do their jobs remotely – particularly if the managers themselves have low autonomy in their work and are closely monitored.4 Delegation and employee empowerment are essential if managers are to trust and lead their employees more effectively.

Besides trust, factors such as professional networks and the ability to adapt over time played a bigger role than technical tools (such as IT or internal training and resources) in supporting people during the pandemic. While technology is certainly one of the primary drivers of value, this finding of the survey highlights how human factors are equally, if not more, important – a tenet that is central to the concept of ‘social enterprise’ first defined in Deloitte’s 2018 Global Human Capital Trends.5

The journey through workers’ eyes

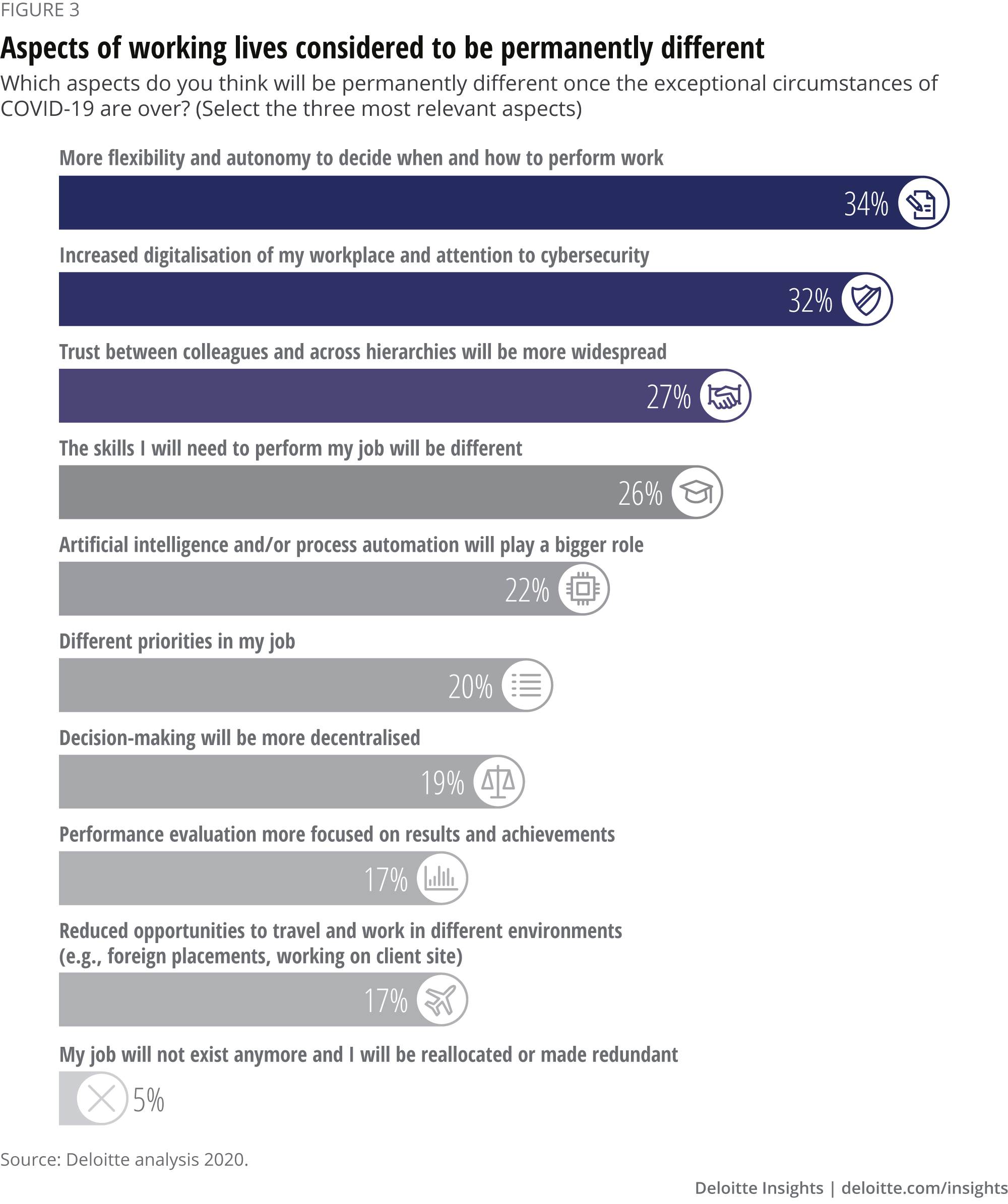

The current situation is clearly exceptional. Restrictions on movement and social interaction will be gradually lifted once a vaccine to prevent infection with COVID-19 or a cure for it are developed and widely available. That might take a long time, however, and there is no guarantee that working lives will return to where they were before. The majority of respondents (66 per cent) expect some aspects of their lives will be permanently different. In particular, remote working seems to be here to stay. The relative majority of respondents expect to have more flexibility to decide when and how to work in the post-COVID-19 world (figure 3). Two in three employees expect to be working remotely more often than they used to, even after the current exceptional circumstances are over – and the share is even higher (70 per cent) among those who had no exposure to remote working before the pandemic.

But, beyond the physical implications, are companies and employees in a position to adapt? With a more dispersed workforce, organisations need to reconsider how they manage performance, learning how to conceptualise, monitor and appraise output and outcomes on the basis of what is delivered. Few respondents, however, expect performance evaluation to become more focused on results and achievements (figure 3). Learning how to manage a more autonomous and less workplace-centred workforce is a big new challenge for organisations. It will involve, too, moving away from old schemes of remuneration and appraisal – evaluation based partly around presence and hours worked. Failing to adapt performance evaluation to the increased autonomy and flexibility of workers would restrict the positive impact that more flexible work arrangements can have. Indeed, fear of having to work more hours for the same pay is one of the concerns about the post-COVID-19 working environment that emerges often among respondents (32 per cent), second only to an increase in job insecurity.

The post-COVID-19 work environment will require new skills from the workforce, and workers seem to be aware of this. Although a shift in skills ranks at the bottom of the changes employees have experienced in recent months (figure 1), it ranks fourth in the list of aspects they expect to be permanently different going forward (figure 3). In particular, 60 per cent of respondents point to the capacity to adapt as one of the top three capabilities that will be more relevant in the post-COVID-19 world. The pandemic might have been for many workers an important wake-up call, signalling not only the pace of change but also its breadth, and the importance of being prepared for it.6 Companies should capitalise on this positive attitude and double down on commitments to build a more resilient workforce. This requires going beyond training workers only in technical skills. Companies should focus on creating an organisational culture and mindset that can foster the ability to learn, apply and adapt new skills.7

Workers are not a monolithic block

The picture emerging from the responses of workers is overall a positive one. In a rapidly changing working environment, most workers have managed to adapt extremely well. But workers are not a monolithic block. Their experiences and views differ.

About one in five workers say they have experienced no change or only a small one to their working lives. Forty per cent of workers have had difficulty adapting to at least one of the changes they went through. One in three respondents do not expect long-lasting changes to the work environment and expect to return to business as usual. Recognising the complexity of their workforce, business leaders need to design their policies and interventions in a targeted way, based on an understanding of their workers’ diverse attributes and needs.

SURFER, GROUNDED OR JUGGLER: How do you see the future?

Workers’ perspectives vary, but three patterns emerge if we cluster responses based on their views and concerns about the work environment post-COVID-19.8 It is important to stress that these typologies are spread across the entire workforce, although they tend to be more prevalent among certain groups.

THE SURFER is convinced that the pandemic has permanently changed their job and expects a shift in the skills and capabilities needed to thrive in the labour market. SURFERS have been able to continue working during the pandemic, but their working life has undergone several changes, not just in terms of more autonomy and flexibility, but also in terms of access to new technologies and more leadership responsibilities. They feel generally positive about their future professional life. A deterioration in interpersonal relationships within the work environment (e.g., a reduction of trust, increased use of data monitoring, or reduction in creativity and possibilities to learn from others) is their main concern regarding the post-COVID world. The surfer is more prevalent among professionals, working in medium or large companies with fixed-term contracts.

THE GROUNDED are not convinced there will be major changes to their jobs and do not foresee major shifts in the skills and capabilities they will need. Their experience of the pandemic has been relatively mild. They report that they have experienced changes to their working life only to a small extent, if at all. Accordingly, they do not have any major concerns about the future work environment and feel optimistic about their future professional life. The grounded tend to be older, engaged in administrative or technical occupations, and working in very large companies (1,000+ employees) with an open-ended contract.

THE JUGGLER has suffered predominantly a loss of access to work. JUGGLERS expect their job to be different once the COVID-19 outbreak is over and believe the skills and capabilities they will need to thrive in the labour market will change. They have a negative view of their future working lives. They are concerned mainly about an increase in job insecurity and a reduction in job opportunities available to them. The juggler is more prevalent among younger workers in sales or customer services, as well as skilled trades and manual jobs, working on fixed-term contracts and in small- to medium-sized enterprises – particularly in the retail and hospitality sectors.

What business leaders should consider going forward

The work environment has changed substantially in recent months and is unlikely to return to what it was before COVID-19. As they chart a path forward, business leaders might benefit from considering the following suggestions:

- Rethink the role of the workplace: If a hybrid arrangement combining remote and on-site work is the way forward, companies need to think carefully about how they define the added value of the workplace in their business model. When going to the office becomes a deliberate decision for employees, the benefit it brings needs to be made explicit and clearly articulated. That requires a deep understanding of what companies and workers expect to achieve in the workplace. It also requires careful consideration of how to bridge the potential disconnect between workers who can and want to embrace a hybrid model, and those who cannot or do not want to.

- Commit to building a resilient workforce: As the results of our survey reveal, workers have adapted remarkably readily to new and exceptional circumstances. Capitalising on this, organisations should consider how to encourage their workforce to continue to grow and adapt their skills so as to be more resilient in a constantly changing world.

- Nourish organisational social capital: With a more dispersed workforce and thus less physical interaction, companies need to be more deliberate in creating and nourishing social capital and transmitting knowledge, common experiences and company culture. In the past, physical proximity has facilitated these exchanges. Going forward, organisations need to be more proactive in setting up opportunities to encourage and share experiences. Building up social capital needs to be considered a strategic goal and a responsibility, particularly towards new hires and younger employees.

Coming next

Following on from the survey results, a series of articles will explore in greater detail three areas that we believe are particularly interesting.

1: Belonging, well-being and ethical concerns

Even before the pandemic gripped the world, business leaders considered it a priority to foster a sense of belonging in the workforce. ‘Belonging’ ranked at the top of the 2020 Global Human Capital Trends survey, with 79 per cent of organisations considering it important for their success.9 In a world where employees expect more autonomy and flexibility, creating a sense of connection among employees and between them and the organisation becomes more challenging. Increased flexibility and autonomy might also mean an increased sense of loneliness and alienation if workers are not managed correctly.

Understanding workers’ experiences with flexibility and autonomy in recent months and what kind of company support has been more effective provides insights on strategies to foster a sense of belonging in the new work environment. Workers’ concerns about the future might help business leaders to not only to create a better working environment but also stay ahead of the ethical issues around employment that COVID-19 has brought to the fore.

2: Knowledge transfer in the new world of work

In the latest edition of Deloitte’s Global Human Capital Trends, ‘knowledge management’ was identified as one of the top three issues affecting the success of a company. Yet very few organisations perceived themselves as ready to address this question.10 The pandemic has further challenged traditional views of knowledge. Corporate culture, common experiences or values were for many companies almost an afterthought. But in an environment in which some employees are on-site and others work remotely, they become essential. Companies need to focus on how to create a culture of knowledge-sharing and creation, and help younger workers develop their skills and knowledge. This is particularly true for early career development, as reduced interpersonal interactions might reduce the ability of younger workers to develop skills and quality networks that can help them grow professionally. The voice of the workforce will help in understanding how the process of acquiring and spreading knowledge takes place, what facilitates it and how new technologies fit in this process.

3: The relevance of going beyond age

Workers’ age has traditionally informed companies’ talent strategies. Programmes for talent acquisition, career and leadership development or learning continue to rely heavily on assumptions about demographics.11 As the workforce becomes more complex and diverse, these assumptions are becoming less relevant. Leaders should recognise workers’ diversity and create a more complete profile of their employees. The voice of the workforce provides an opportunity to analyse the role that age may play and help develop more personalised policies and programmes to foster belonging and knowledge-sharing within the company.

Explore more from the Future of Work collection

-

Superlearning Article4 years ago

-

Inclusive work: Marginalized populations in the workforce of the future Article4 years ago

-

Passion of the explorer Article4 years ago

-

Returning to work in the future of work Article4 years ago

-

Human inside: How capabilities can unleash business performance Article4 years ago

-

Innovation in Europe Article6 years ago