Passion of the explorer How companies can instill the motivation to learn, develop, and grow

13 minute read

17 August 2020

John Hagel III United States

John Hagel III United States Maggie Wooll United States

Maggie Wooll United States John Seely Brown (JSB) United States

John Seely Brown (JSB) United States Alok Ranjan India

Alok Ranjan India

Leaders are calling for reskilling, capabilities development, and reinvention of how we work. But all of this makes demands on workers, especially in a time of crisis. How can companies encourage employees to make the effort?

Introduction

Leaders are increasingly looking for employees to break the confines of their job descriptions, looking for problems and for creative ways to solve them. But for most people, employers can’t expect this attitude shift to just happen. It takes real effort to shift to a mindset of continuous learning and searching. And a first step to instilling passion across the workforce is understanding why some people take on the challenge.

Learn more

Explore the human capital collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

What compels a customer agent to look for a better way to support testing decisions by doctors, a farmer to question the irrigating technique for a beet field, a factory worker to identify more ways to use a “job-killing” robot, a video technician to delight basketball fans with new visual experiences, or a programmer to protect children on social media from harmful advertising? What compels a marketer to experiment with new ways of using remote collaboration tools rather than accepting as “not ideal but necessary” endless days of virtual calls, misalignment, and review cycles? What compels an IT support technician to tinker with the way tickets are addressed even though it requires extra effort to learn about bots and automation that could threaten her job?

Something propels these workers past the obstacles and doubts: No one is asking for it; it’s not in my job description; I don’t want to waste anyone’s time; this is the way we’ve always done it; I don’t know anything about this new technology; automation will take my job; if this doesn’t work, I’ll be fired; if this were a good idea, we’d already be doing it; I’m supposed to have answers, not questions; I don’t even know enough to know if there’s a there.

What motivates workers to move beyond these and try, learn, and try again in the face of uncertainty and headwinds? We’d better find out, because companies need the workforce’s full sensing, scouting, innovating, and learning power to adapt to changing conditions and capitalize on emerging opportunities.

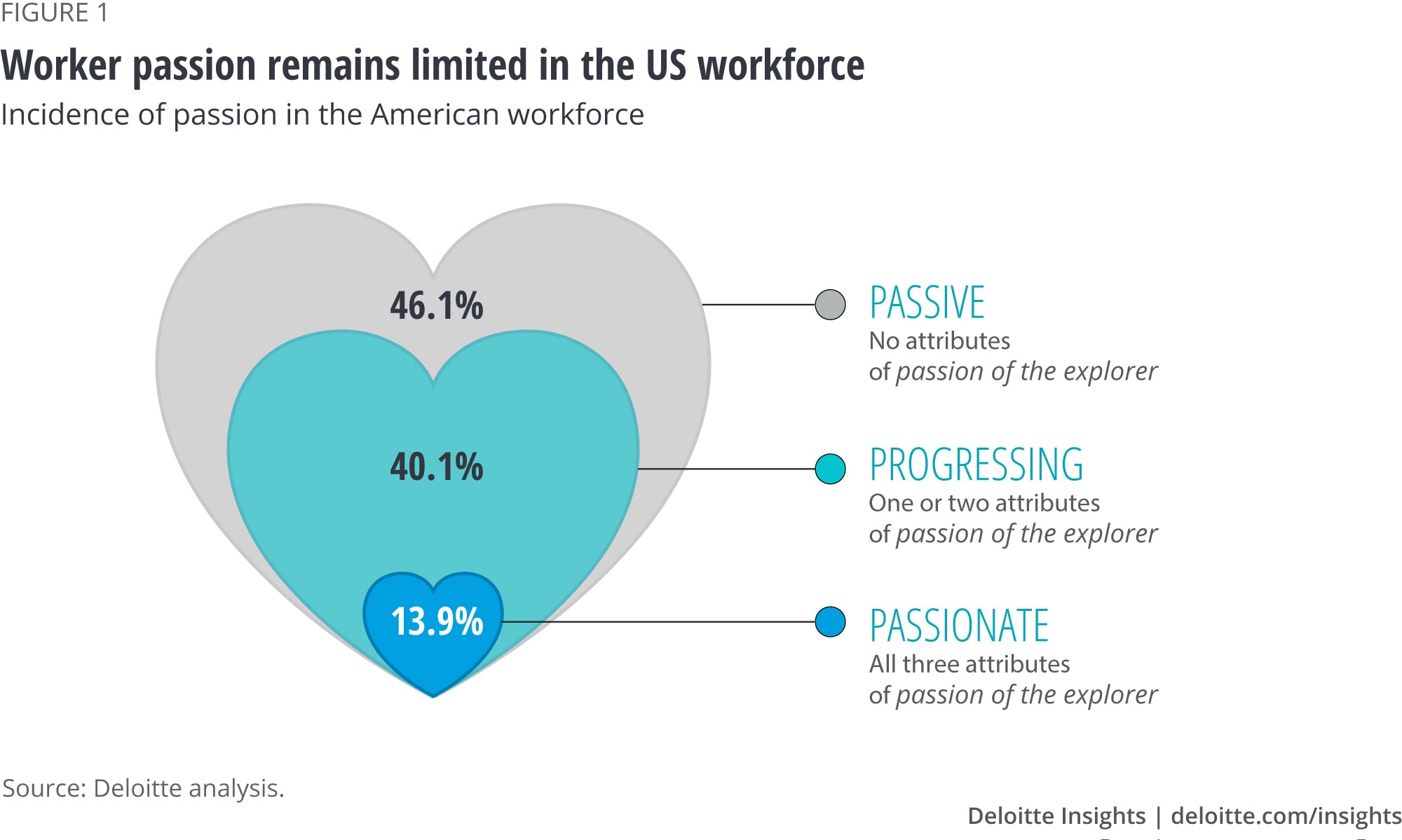

An absence of passion

Companies face a shortage of passion in the workforce. In our recent survey of US workers, taken before the COVID-19 shutdown,1 a mere 13.9% of respondents demonstrated the type of passion to take on challenges, push boundaries, and connect with others in order to develop better ideas and more creative approaches. Across industries, regions, and generations, this passion of the explorer—defined by the disposition to both seek out difficult challenges and connect with others in order to learn how to do better, to be more effective, to have more impact2—is in short supply at work. Far worse, 46% of the workers surveyed were passive, demonstrating none of the key attributes. As we talk about skills gaps and workforce shortages, new ways of working, tapping into core human capabilities, and the growing need for workers to own their own learning and careers, this lack of passion should cause some alarm. The passion of the explorer is a key part of the motivation needed for learning new skills, tools, and approaches, for taking on difficult or ambiguous challenges, for revealing ourselves and becoming vulnerable by deploying our most human capabilities.

Without that passion, companies may struggle—and so will workers.

Exploring the explorers

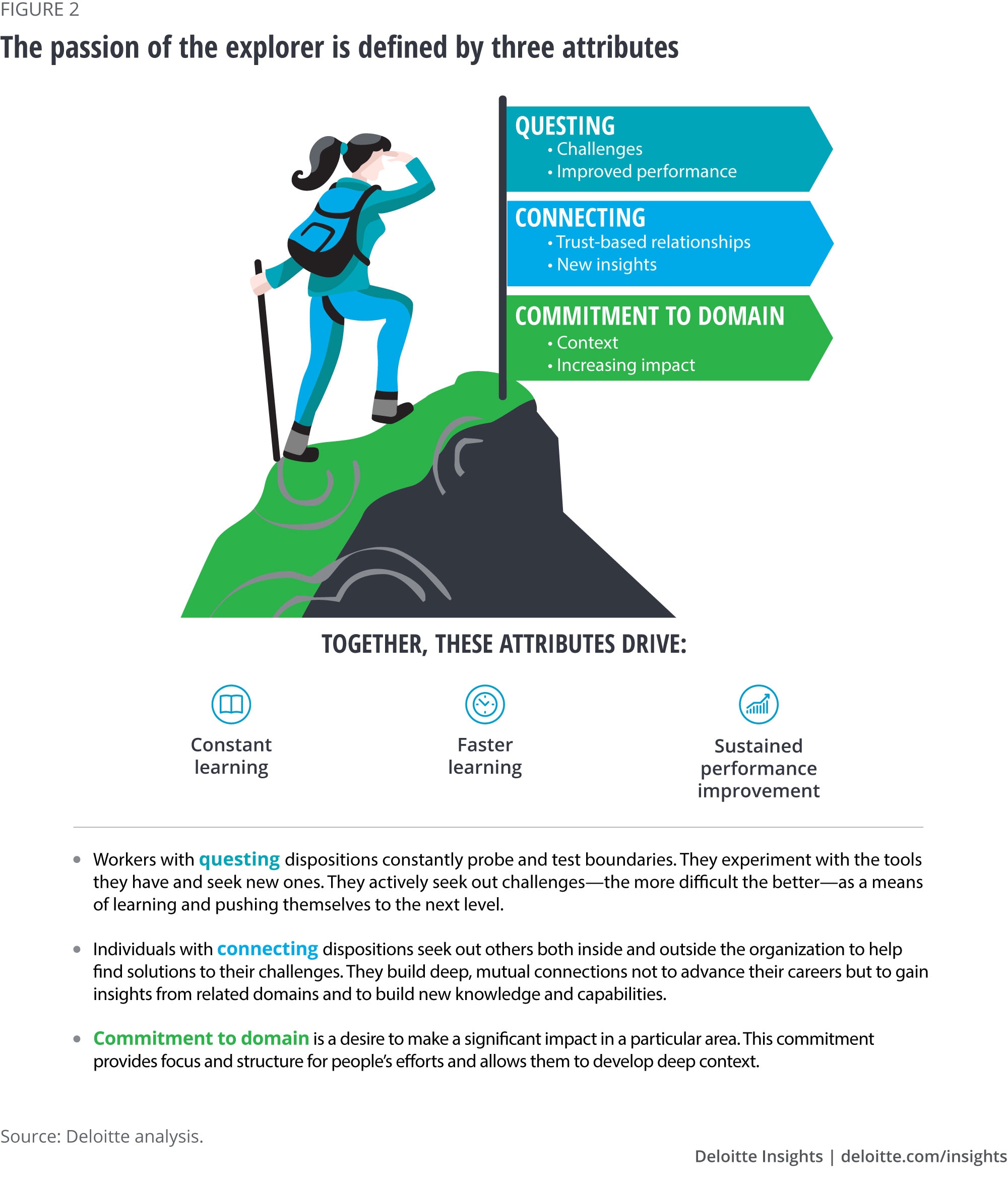

When we talk about worker passion, passionate workers, or explorers, what we mean is a worker who exhibits three attributes—questing, connecting, and commitment to domain—that collectively define what we have termed the “passion of the explorer.”3 We will use these terms interchangeably throughout this article.

What is passion?

Passion, the specific type we call the passion of the explorer, can fuel the individual’s motivation for learning. And although it’s often uncommon in the workplace, this type of passion—to take on challenging problems, to connect with others to learn how to better address them, and to have a desire to make a significant impact on the field over time—isn’t confined to certain ages, geographies, or industries. In past years, we’ve looked at this question in depth and found no significant correlation between passion and these characteristics.4 There’s no reason to believe that most people aren’t capable of developing the attributes of passion, assuming they are in the right environment, and companies may find fertile ground for fostering passion, a finding supported by the 40% of respondents who already demonstrate one or two attributes. In fact, 87% of respondents report having and pursuing a passion, although only 25% report discovering their passion through their work. While many pursue passions independently, the findings show that most US workers surveyed haven’t managed to effectively connect passion to their day-to-day work.

Why does it matter?

Today, it might be easy to dismiss the idea of passion: Whether workers feel passionate about their work might seem like a nice-to-have during a crisis. But having employees with the passion of the explorer for the work they do may be even more critical, assuming the business wants to evolve, adapt, and act rather than merely react to a rapidly changing world. In short, in an environment of accelerating and unpredictable change, the passion of the explorer is key for thriving.

Passion is an important but often-missing element in how companies think about developing the workforce for the future. Whether that means cultivating enduring human capabilities or training and reskilling, we found a significant difference in outlook and orientation toward learning between the passive and workers with the passion of the explorer. Many of us claim to love learning. But learning about a new topic—of our own choosing, on our own timeframe, and with no baggage or consequence attached—is easy. What about learning that is less about and more how, why, what else, and what happens if? Learning that happens in real time, in the flow of work, through considered risk-taking and productive friction with a diverse mix of collaborators—that is harder. The learning that companies will find most important will require employees to get out of their comfort zone, to try new things and let go of old ones, and to be present and attentive with others. Not only are the passionate oriented toward seeking out challenging opportunities and connecting with others to learn faster—they are overwhelmingly confident in their ability to learn and adapt5:

- Ninety-six percent of passionate respondents (versus 59% of the passive) reported feeling confident of remaining relevant as technology changes work and the workplace.6

- Ninety-one percent of the passionate (versus 48% of the passive) strongly or completely agreed that when they need a new skill, tool, or resource, they can easily figure out how to acquire it in a way that fits their current need.

- Ninety-eight of the passionate (versus 56% of the passive) believe that they can face any technology disruption at the workplace and are always eager to learn.

- Eighty-nine percent of the passionate (versus 46% of the passive) welcome changes in work and workplace even if it takes a while to adjust.

We’ve written elsewhere about the imperative for business to help employees adopt new behaviors that use and develop enduring human capabilities such as curiosity, imagination, creativity, empathy, and courage.7 Few workers will evolve and change their behaviors without motivation. Exposing your underdeveloped human capabilities to coworkers, investing yourself and risking failure, putting in the effort to notice and question what you’ve always done, putting in the effort to learn new behaviors and skills: This can be hard, uncomfortable work. Why would anyone do it? In general, it won’t be because of a specific incentive or the hope of checking a box on a future performance evaluation. While we shouldn’t lose sight of the role that extrinsic factors such as financial stability and recognition play in motivation, intrinsic motivation—passion—may be more potent for the kind of sustained daily effort and courage needed for continuous learning, skills, and capabilities development, and working with others under dynamic and challenging conditions.

When it comes to trying out their human capabilities in the work, the passionate were more likely to engage in the behaviors associated with curiosity, imagination, creativity, and empathy:

- Explorers are willing to raise questions in order to better understand the work. Nearly every passionate worker looks to achieve a better understanding of a problem or situation; only 38% of the passive have a similar outlook.

- Ninety percent of the passionate (versus 45% of the passive) report regularly challenging their assumptions and considering what else is possible.

- Eighty-seven percent of the passionate report regularly working to adapt their thinking, assumptions, or behaviors to new conditions; 90% improvise and use resources in new or unexpected ways. By contrast, 44% of the passive believe that these capabilities are not beneficial to their work.

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, the passionate overwhelmingly believe themselves to have enduring human capabilities, while less than half of passive see themselves as creative, curious, imaginative, or empathetic.

Finally, as we move toward a future of work that is more often interdependent and collaborative, it is interesting to note that passionate workers are more positive about the value of teamwork than are the passive.

- Ninety-four percent of the passionate report enjoying working in a group; just under 40% of the passive share that outlook.

- Eighty-six percent of the passionate believe that they could not accomplish their work objectives without working as a group.

- Eighty-two percent of the passionate report spending more than half of their time working in teams.

What gets in the way of passion?

If passion is a significant motivator of the type of learning that will be most valuable to companies and their workforce in an increasingly dynamic and unpredictable future, what can companies do to foster and tap into employee passion? Our survey revealed significant differences in how the passionate and passive perceive differently their work environment and opportunities.

Both the work and work environment influence the development of passion:

- Compared to others, the passionate were more likely to have discovered their passion through work rather than choosing work that matched a passion. Just over half of the passionate report discovering their passion through their work; 29% chose a profession based on a passion they already had.

- As the degree of teamwork increases, the worker is more likely to be passionate. A significant proportion of the passive (48%) spend less than a quarter of their time in a team/group work environment. Meanwhile, more than half of the passionate report spending three-quarters of their time in a team environment.

- Encouragement to pursue interesting work increases the likelihood of passion. Some 82% of passionate workers report being encouraged to pursue projects of interest even if that work belongs outside their direct responsibilities; only 17% of the passive report the same encouragement.

- Mentorship also helps provide guidance and better awareness of opportunities for learning. Only 19% of the passive reported having access to mentorship, compared to 84% of the passionate.

- The passionate are more likely to report having access to resources and tools to perform better and create more impact. Access makes it easier for employees to begin experimenting and playing with new ways to accomplish a task or approach a problem and offer some agency. Only a quarter of passive workers report having access to resources and tools.

- Similarly, a sense of autonomy plays a crucial role in inspiring workers to think creatively and come up with new ways to perform a task. Fully 90% of the passionate report having autonomy to achieve their goals, versus 31% of the passive.

- Finally, among the passive, there is a sense of not participating in the changing world. Only 39% of passive (versus 79% of the passionate) agree that, “My day-to-day work and what is expected of me have changed significantly over the past three years,” and only 40% (versus 85% of the passionate) agree that, “The business and competitive environment for my company have changed significantly over the past three years.” It seems likely that if people perceive less change, they may also perceive fewer opportunities to learn, grow, and make an impact.

There were some interesting areas in which the passionate and passive did not diverge. These commonalities may speak to the challenges that companies will face moving into the future. Most respondents, 83%, passionate and passive, report that routine and predictable tasks still comprise more than half of their work. This is notable as automation and AI become more and more capable of taking on routine, predictable tasks. In addition, both the passionate and passive pointed to a work environment focused on speed and efficiency as a top factor preventing efforts to develop new approaches or use more human capabilities at work.

What else motivates us?

Of course, motivation—in and out of the workplace—comes from more than just passion. Mindset and beliefs play a role, as do our emotional, social, financial, and even physical resources at any given time. Fear can be a powerful motivator for some, especially in the moment. Anecdotes abound of leaders who faced imminent disaster, destitution, or collapse of a business and who averted the looming failure by redoubling their efforts, making desperate calls, taking terrifying risks, or digging deep for creative workarounds. In general, however, fear tends to limit our ability to perceive options. Over time, if we perceive mostly threats—of job loss; loss of status, identity, and relationships; loss of financial stability and well-being—these fears work against learning, vulnerability, and growth. We become defensive and reactionary, our vision narrows, and what learning happens is confined to executing within that narrow tunnel. In a rapidly changing world, those motivated by fear will tend to burn out and become less effective and increasingly marginalized.

At the same time, the workforce has legitimate fears. Passion can be an antidote to fear, but the fears of the workforce are real. Between 20 and 40 million American workers have lost jobs since March 20208—many of them permanently. Workplaces are closed. The future is uncertain. Left unchecked, those fears can overwhelm passion, especially if it is just beginning to emerge. If organizations hope to benefit from employees’ passion, they should consider asking two questions: In what ways are we creating a work environment that supports and draws out workers’ passion? And in what ways are we contributing to employees’ financial, emotional, social, and physical well-being, and in what ways are we destabilizing it?

Efforts to reskill, cultivate capabilities, and encourage new ways of working may be wasted if companies don’t focus on the environment and address the underlying demotivators associated with a lack of passion.

At the same time, if companies can unlock the passion of their workforce, employees may more actively drive their own learning and development. This becomes especially important as jobs/roles become less clearly defined and evolve more rapidly, making it harder to match a role to an individual’s set of preferences. Instead, passion can help overcome the elements of a role that are more challenging. Stoking passion can tap into a worker’s desire to learn faster how to have more impact, to take on challenging problems, to reach out and collaborate with others to better understand the nature of a challenge and develop better solutions.

We began this article by saying that companies face a shortage of passion in the workforce. It might be more accurate, and optimistic, to say that the American workforce is suffering less a shortage of passion than a place to put it. Findings suggest there’s no shortage of passion in individuals, but most haven’t found a way to connect passion to their work. Companies largely aren’t benefiting from the enthusiasm, energy, and creative problem-solving that workers are directing at other areas of their life. It’s a missed opportunity—one that leaders shouldn’t overlook, even at a time when business and society seem to be lurching from crisis to crisis.

More on human capital

-

Superlearning Article4 years ago

-

Building the peloton Article4 years ago

-

Beyond reskilling Article4 years ago

-

If you love them, set them free Article7 years ago

-

Passion versus ambition Article10 years ago

-

Talent Collection